21 minute read

EYES ON THE PRIZE: COLLEGE

EYES ON THE PRIZE

By Chelsea Kellner

From teenage packing plant worker to animal science student and mentor, Sampson County’s Selena Ibarra is a first-generation college student who refused to quit.

Selena Ibarra was 14 years old when she started work at a packing plant to help pay the bills for her family of 13.

Fingers flying, Ibarra could strip the seeds from a bell pepper in under two seconds. Slower workers didn’t last long. The job required Ibarra to stand for hours, and lunch breaks depended on workload.

So when Ibarra decided she wanted to leave rural Sampson County to attend university in the state capital, she had already developed the persistence and work ethic needed to be first in her family to figure out the system.

“I constantly called staff members about the application process, because

I had no idea how to apply — I had no one close to me to go to with questions,” Ibarra says.

Her dream: a master’s degree from NC State in an animal-related field, followed by a stable job and her own small farm someday.

Step one: an acceptance letter.

Falling In Love With NC

Born in Oregon, Ibarra and her family moved to North Carolina when she was 10. Her father, a farmworker, kept getting pneumonia from field work during Oregon’s harsh winters.

“The plan was to stay in North Carolina only until my dad felt better, but my parents ended up falling in love with the state,” Ibarra says.

So Ibarra grew up in Turkey, North Carolina, a tiny eastern town just half a mile square. The population hovers around 300. Her family didn’t own a farm, but they raised chickens and collected the eggs. The Ibarras attended a local “farm church,” where most congregants had agricultural jobs and sang hymns in their work clothes. Since her large family had to share a single car, Ibarra’s world revolved around school, church and home.

She started working summers at the packing plant during the 2007 recession, when her dad’s canning factory job was slashed to two days a week. But her dream continued to grow: Animal science. Master’s degree. CALS.

If One Door Closes…

No one in Ibarra’s family had attended college, but it wasn’t their first time tackling a complex bureaucracy from the outside. Born in Mexico, her parents had successfully navigated the United States immigration system to receive citizenship decades before. They encouraged Ibarra as she toiled over her NC State application.

But even with hard work, her first attempt met with disappointment: a rejection letter in her mailbox.

“I got very discouraged,” Ibarra says. “But I thought, if you get a letter saying ‘no,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean no — there are other options, you just have to look for them. It might So she called back one more time. That’s how she found out about the Agricultural Institute, CALS’ focused, hands-on associate degree program allowing students to dive directly into agriculture.

The odds against Ibarra were steep. First-generation college students are less likely than their continuinggeneration peers to persist through the first couple years of college, according to the U.S. Department of Education — and in one study, only 17 percent had attained a bachelor’s degree eight years after high school graduation.

But two years after Ibarra’s acceptance into the Agricultural Institute, she earned her associate degree and transferred into the Department of Animal Science. Now 24, she’s a senior animal science major, getting ready to graduate.

Together with our partners, we put nature’s tools — enzymes and microbes — to work in agricultural solutions to increase the efficiency of crop and livestock production. Every time Ibarra heads home for a visit, she coaches her 10 younger siblings along their own college track, proofreading personal essays and explaining who to call in the admissions office. Three of her siblings have already followed in her footsteps, one to the University of North Carolina and the others to community colleges; another is on track to graduate from an early college program.

“I would advise other students in my situation to reach out,” Ibarra says. “It’s important to realize that education is so valuable but that the system can be complicated, and you have to ask somebody who’s in the field.”

Ibarra’s commitment to education still manifests through hard work. At her internship on a mountain farm last summer, she worked 50 hours a week or more, building fences and hauling produce to the farmers market.

And instead of slinging seeds at the packing plant, she now has a steady job at the NC State gym to raise money for school.

“I love college,” she said. “I’m very happy — and very appreciative — to be here.”

There’s More Than One Path To CALS…

Selena Ibarra’s CALS journey led her through the two-year Agricultural Institute. Go online to

go.ncsu.edu/PathsToCALS

to find your best path.

WE BELONG TOGETHER

— Mike Walden, CALS Economist and Extension Specialist “Urban areas can’t thrive if rural areas don’t thrive, and vice versa. We’re all in this together.”

— Patrick Woodie, President,

North Carolina Rural Economic

Development Center

CALS RURAL OUTREACH ACROSS THE STATE

HEALTH MATTERS FOR EXTENSION

Each year, NC State Extension’s family and consumer sciences program makes approximately 1 million educational contacts throughout North Carolina, sharing knowledge on healthy nutrition, physical activity and chronic disease reduction.

When two Halifax County churches decided to build a community garden, two obstacles stood in their way: They had no water source, and they had no money for equipment, seeds or other supplies.

But with a grant from NC State Extension’s new Health Matters program and expertise from Area Horticulture Agent Victoria Neff, the churches’ garden now provides produce to over 350 families.

The garden is one of 60 wide-ranging projects by four Health Matters associates and their 110 community partners last year to increase access to healthy food and physical activity.

“Oftentimes there’s a misconception that living a healthy lifestyle is just about individual choice, but what we often find in low-income and rural communities is that choices aren’t even there,” said Lindsey Haynes-Maslow, one of the principal investigators.

Funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Matters works in four counties where more than 40 percent of adults are obese. But individuals’ weight loss won’t be the measure of the project’s success.

Instead, Haynes-Maslow and fellow principal investigator Annie Hardison-Moody, both assistant professors with the Department of Agricultural and Human Sciences, say that Health Matters will be successful if it strengthens ties between Extension and other groups to help overcome health-related disparities.

In designing the project, the researchers worked in partnership with faculty members from NC State’s departments of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management and Sociology and Anthropology.

Rooted deeply in social and economic inequities such as community infrastructure and job scarcity, the disparities that affect people’s health can’t be resolved overnight, HaynesMaslow says. But Health Matters helps communities take steps in the right direction.

BIOTECHNOLOGY BOOT CAMP FOR BERTIE

A dozen high schoolers from Bertie County, North Carolina, got handson laboratory training at a summer biotechnology boot camp run by Matt Koci, an associate professor in the Prestage Department of Poultry Science, and Bruce Boller, a science teacher at Bertie Early College High School.

The goal of the weeklong camp? To give students from one of the poorest counties in the state an opportunity to dive into college-level science at one of the best universities in the nation.

During their visit in July, the students’ packed schedule included everything from hands-on lab training to visits with biotech companies in the Research Triangle Park.

“It’s difficult for most of these students to connect abstract independent laboratory modules back to their daily lives, or more importantly, to the jobs and careers they see in their community,” Koci said. “We’re trying to change that.”

— Suzanne Stanard

LOANS FOR:

• Buildings and fences • Lands and lots • Timberland • Equipment • Acreage • Homes

go.ncsu.edu/BiotechBootcamp

HERE TO HELP YOU GROW

Living in the land of opportunity means there’s always fertile ground. People looking to make a life in rural America have had a trusted financial resource in Farm Credit for a century. Offering full and part time farmers, young producers, and rural homeowners the support they need to keep growing. Call one of our experts to see how we can help keep you growing.

AGCAROLINA | CAPE FEAR | CAROLINA farmcreditofnc.com

FASTER ANSWERS FOR CATTLE FARMERS

By Dee Shore

Science-based solutions are reaching North Carolina’s beef cattle producers quicker, thanks to recent changes at the state’s agricultural research stations.

When physiologist Daniel Poole joined CALS in 2011 to research ways to improve reproduction rates in beef cattle, he faced significant challenges to testing his ideas.

But modifications at North Carolina’s agricultural research stations in the years since have changed that, reducing the amount of time it takes to gather data — and speeding up communication with farmers.

That means that NC State is able to make management recommendations to farmers much sooner.

What’s changed?

In the old system, herds at the eight research stations where NC State cattle research takes place were managed differently.

Animal Science Department Extension Leader Matt Poore has a similar perspective. Because cattle are being raised under the same biosecurity protocols, Poore said, researchers can move cows from one station to another without worrying about spreading health problems. As Poore and Poole look ahead, they see more improvements on the way.

Poole said. “Another thing we want to do is to grow our herd up at the Butner Beef Cattle Field

Lab, from around 200 now up to 500 cows in the future.”

While faster research is the biggest advantage researchers have seen so far with the changes, Poore noted that the shift has also spurred more

interdisciplinary livestock research. Experts in crop, soil, animals and veterinary sciences are already collaborating on a range of projects, from soil health to feed efficiency to fescue toxicity.

That kind of collaboration will be increasingly important as CALS frames a food-animal initiative aimed at solving problems that farmers face across the state.

RESEARCH STATIONED FOR IMPACT

Through a network of 18 research stations (six maintained by NC State) and seven field labs, NC State research and Extension track down solutions and extend research-based knowledge to growers across the state.

Through research on just five crops — tobacco, sweet potatoes, cotton, blueberries and soybeans — we generate a $1.67 billion annual impact to North Carolina’s economy — and about $1.45 billion of that directly impacts Tier 1 and 2 counties, helping grow prosperity where it’s needed most.

Above: Ornamentals researcher Nathan Lynch eyes up black-eyed susans at Mountain Horticultural Research and Extension Center in Henderson County. Opposite: Nate Maren, grad student researcher at the Center, examines cultures in a lab. Top left: Student Chelsea Brown takes samples in a lab at the center.

CONSERVATION PIONEER LEAVES LASTING LEGACY

By Suzanne Stanard

NC State philanthropist and early conservationist William Stevens helped hundreds of students attend CALS — and his nephew, Senator Richard Stevens, understands the real meaning of “conservation.”

One day when Richard Stevens was a teenager, his uncle asked him if he knew what conservation meant. The answer stuck with him for the last 50 years, as vivid as when it was first spoken.

“I had kind of a tree-hugger impression of what conservation meant,” he said. “And my uncle said, ‘No. Conservation means the wise use of our resources.’ I’ve never forgotten that. The earth is filled with resources, and we can deplete them or use them wisely. And that was his philosophy: replenishment, replanting, reuse, taking care of our earth.”

His uncle, the late William Walton Stevens, was a conservation pioneer who dedicated his life to the cause. He and his wife, the late Emily Inscoe Stevens, didn’t have children, but were committed to fostering future generations of conservationists.

That’s why they established the William Walton and Emily Inscoe Stevens Soil Conservation Fellowship/Scholarship Endowment in 1982, which benefits NC State students studying a variety of subjects related to conservation, including soil science, natural resources, forestry, horticulture and others.

Today, the endowment produces 12-15 scholarships per year.

“My uncle grew up on a farm as one of eight children and lived through the depression, so I think, in that generation, you appreciated and you conserved what you had,” Richard Stevens said. “As a young person, he had observed the abuse of natural resources and became determined to do something about it.”

After earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees from NC State, William Walton Stevens served in various positions with the state Soil Conservation Service and finished his landmark career in a top post with the state Office of Earth Resources. He also served 32 years in the U.S. Army in active duty or as a reserve, earning the Purple Heart and Bronze Star.

Stevens received three meritorious citations from the USDA, was elected a fellow in the Soil Conservation Society of America (its highest honor) and was awarded the Governor’s Conservation Award by the Wildlife Federation of North Carolina, in large part, as the ceremony script says, because “he talks, lives, believes, and acts for the causes of wise conservation.”

And he remained committed to NC State, through contributions of estate gifts over the years that supplemented his endowment. He also received the NC State Alumni Association’s Meritorious Service Award in 1995 and endowed the Stevens Nature Center at Cary’s Hemlock Bluffs Park.

“He realized how important NC State was to him as a farm boy in the 1920s to be able to go to college and get a degree, and he and his wife wanted to give back,” Richard Stevens said. “I think he’d be very proud of the accomplishments of literally the hundreds of young people he has helped go through school.”

TALLEY-ING UP THE TURKEY UNIT

Thanks to a visionary gift from the Talley family, the newly named Windell and Judy Talley Turkey Education Unit will boast renovations to improve biosecurity, decrease labor costs and boost turkey research productivity.

When current poultry science Ph.D. student Brooke Bartz first set foot on NC State’s campus, she wasn’t planning on pursuing a degree at CALS.

Then she toured the Turkey Education Unit.

Through her tour of the facility, Bartz saw a chance to conduct research she’d dreamed of: improving farmers’ abilities to rear birds with economic efficiency and a high level of animal welfare.

“A 20-minute farm tour turned into a life-altering opportunity,” Bartz told the Talley family at the unit dedication event in February.

The family’s gift and naming of the unit will allow remodeling, improved biosecurity, decreased labor costs and faster turn time, with a net result of greater turkey research productivity. Remodeling of one unit will provide a facility to study the effects of lighting on rearing commercial turkeys. Remodeling of another will create a venue for studying intestinal health in turkeys.

Pat Curtis, head of the Prestage Department of Poultry Science, called the Talleys’ gift “momentous.” And for Bartz, it was even more personal.

“Without your support,” Bartz said, “I would never have found my calling in the poultry industry.”

MEET THE TALLEYS

Windell Talley has been an agricultural producer in Stanfield, North Carolina, for 51 years, providing a grain market for area grain farmers using corn and wheat for feed production in his feed mill. That feed sustains Talley turkeys and cattle, with some outside custom feed sales. A CALS alumnus, Windell and his wife, Judy Talley, have three sons who are NC State graduates and who returned to join the family farm operation.

The Talleys’ work with CALS traces back to Windell’s poultry science degree in 1963. At the dedication, he spoke of his recent work assisting CALS researchers with on-farm research into early use of enzymes.

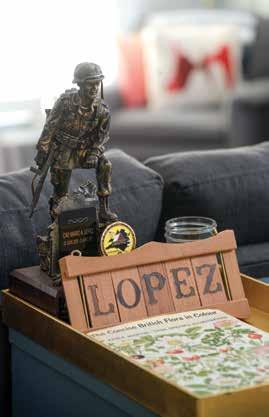

Food safety isn’t the first thing that comes to mind for most people when they think of military service, but it’s crucial. From soldiers’ field rations to their families’ groceries on base, every scrap of food is inspected. “Military service members need to be in tip-top shape to do our jobs,” Lopez says. “If the food source is tampered with, if it is unwholesome, that stops the war-fighter — and that’s not only for soldiers, but also for their families and anyone else affiliated with the military. It has an overwhelming affect on how the military functions.” Lopez is the latest in a line of service members stationed at CALS, says Keith Harris, associate professor and undergraduate coordinator in the Department of Food, Bioprocessing and Nutrition Sciences. Harris himself served in the Marine Corps: first the reserves, then called into active duty in the Persian Gulf War. The self-discipline, leadership and organizational skills of military training translate well to the classroom, Harris says. During Lopez’s time at CALS, Harris has watched him mentor his fellow undergraduates, most of whom are a decade younger. “He could just walk in and take over, because he knows very well how to effectively manage a team — but instead he’ll make a suggestion, and then he’ll sit back and listen rather than micromanage everything,” Harris says. “That, to me, is a very effective mentor.”

The Making Of A Military Man

Lopez didn’t need to join the Army. He had two good jobs in his hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan, working for Coca-Cola and as a supervisor at an automotive repair facility. But something was missing. “I made a promise to myself at the age of 20: that if I didn’t feel I was progressing where I was, I would join the military,” Lopez says. “I felt that I was capable of much more than I was

actually doing.” Lopez entered basic training as an enlisted soldier and worked his way up to sergeant as first a veterinary food inspection specialist, then a warrant officer — a subject matter expert.

The most difficult part of his transition back to the classroom was adjusting to ways technology is now integrated into every lesson. Educational use of the internet was in its infancy when Lopez graduated high school.

Being stationed at CALS also broadens the options available to soldiers like Lopez after they retire, opening up possibilities in the private sector that may require a degree.

For now, Lopez hasn’t reached a decision on the timing of his retirement, or what he’ll do when he’s no longer an active duty soldier. But he and Emily have lived on bases around the world together, from Camp Zama, Japan, to Joint Base Louis-McCord in Washington. His next assignment after graduation will be his first unaccompanied tour — the couple decided that it was better for Emily to stay in their house in Angier, North Carolina, for the year that Mario is in Korea.

After almost two decades of moving together around the world, this is one house they’re not going to sell, Lopez says: North Carolina feels like home.

— Chelsea Kellner

#AGPACKSTRONG

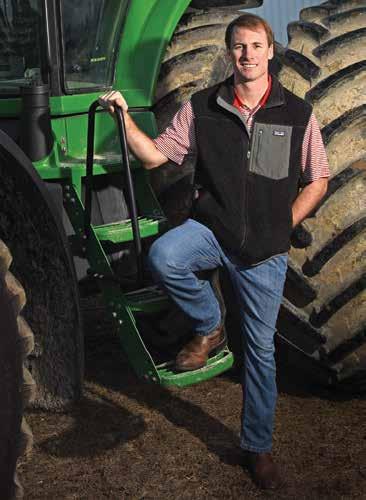

From Little Washington to Israel: Archie Griffin, CALS ‘12 2017 Nuffield Scholar

What was it like growing up in a rural area?

I participated in the farm, but it was never my cup of tea. When I went off to State, I had no intention whatsoever of coming back to the farm. Ever. I wanted to get out and experience big city life. I told Dad I was going to sell the farm.

What did your dad say to that?

He just kind of smiled. [laughs] I would say that was some immaturity on my part. … Once you do return, it’s well worth it. It’s not as big a change as you would think.

What makes moving back worth it?

In Raleigh, you feel like you’re just another person, and you don’t know that your actions are making that big of a change. In rural North Carolina, every action you take is making a drastic change in not only your rural community, but on your big cities.

Out here, if the local produce farmers have a bad year farmwise, not only are the prices of, say, cabbage or corn going to go up in your local grocery store, they’re also going to increase in Raleigh.

What are some misconceptions about working in agriculture?

Nowadays, there’s technology in every aspect of what we do. … Farming technology has advanced so much that when I interview somebody, the first thing I ask them is: “Did you play video games growing up?” And I’m hoping they’ll say yes. Because in the sprayer or the tractors, I might glance up at the field every once in a while, but I’m mostly staring at a computer screen.

There are so many opportunities. Because of farming, I leave in early March to travel around the world doing research

on agricultural technology through a Nuffield International Farming Scholarship.

What are your travel plans?

I’ll do a two-month span in the Netherlands, then Ireland, Brazil, Mexico, Canada and New Zealand. Then they give me a budget and let me travel wherever I want until the budget runs out.

I’m focusing in on Israel, Jordan and the Middle East. Israel is probably the most technologically advanced country in the world when it comes to agriculture — they’re actually growing crops sustainably in the desert. Technology-wise, they’re probably at least 20 years ahead of us. Afterward, I plan to come back to my family’s farm, once again.

JOIN US AT SEPT. 8 FOR State’s Biggest Tailgate!

Imagine over 2,000 of your classmates, friends and family celebrating the Pack together.

That’s the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Tailgate! Please join us this year — our 27th — and enjoy good food with family and friends, including our own delicious Howling Cow ice cream. It’s all part of Ag Day, with exhibits and activities for one and all. And, of course, the big game against the Georgia State Panthers. Mark your calendar and get your tickets today!

Saturday, Sept. 8

3 hours before kickoff PNC Arena, West Entrance (gametime to be announced)

Mr and Mrs Wuf are going to be there. How about you?

cals.ncsu.edu/tailgate Contact us at 919 - 515 - 7222 or calsalum @ ncsu.edu

NC State University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Campus Box 7508 Raleigh, NC 27695

NON PROFIT ORG U.S. POSTAGE PAID

RALEIGH, NC PERMIT No. 2353

Stay connected to CALS every week!