3 minute read

Decision 1920

Decision 1920 A Return to “Normalcy”

By Paul Durica and Alex Teller

Advertisement

Decision 1920: A Return to “Normalcy” runs September 15 – November 25

In 1920, American voters (including women for the first time) went to the polls amid profound change and turmoil. The aftershocks of World War I and the 1918 influenza pandemic were still being felt, prohibition was raising questions about the government’s right to restrict individual behavior for the common good, and racial violence had erupted across the country during the “Red Summer” of 1919.

Decision 1920, on view at the Newberry through November 25, puts visitors in the shoes of the voter faced with a monumental question 100 years ago: embrace change and move forward or go back to how things were at the beginning of the century?

“The 1920 presidential election is notable for how it echoes in the present but also for how it differs from 2020,” says Paul Durica, Director of Exhibitions at the Newberry. “In 1920, as in 2020, the candidates offered starkly different visions for how America should respond to cataclysmic events. But race went largely unacknowledged by both parties—a silence that speaks volumes as we look back on this moment today.”

“The G.O.P. Looks Good to Me.” Boston: Suffolk Music Publishing, 1920.

Promotional material for the Democratic ticket, James M. Cox and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Harding conducted much of his campaign from the front porch of his home in Marion, Ohio. Postcard by Curt Teich and Company, ca. 1923.

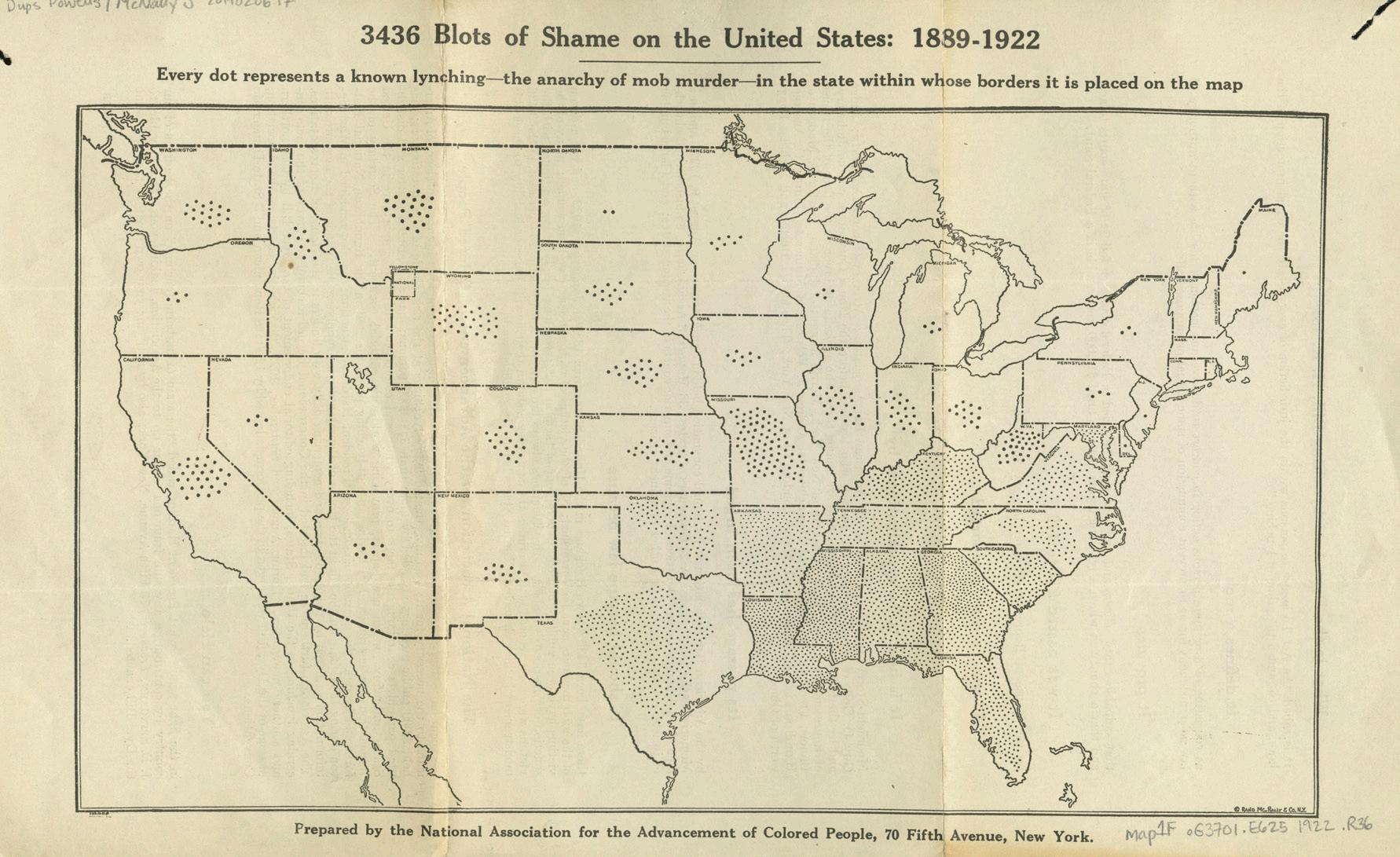

This map, showing the sites of 3,436 lynchings across the United States, was published as part of the NAACP’s national campaign in support of a federal anti-lynching bill in Congress. The bill made it through the House of Representatives in 1918, but it was blocked by Southern Democrats in the Senate. Women’s suffrage extended gradually across the United States before the passage of the 19th Amendment. Illustration from Puck magazine, 1915.

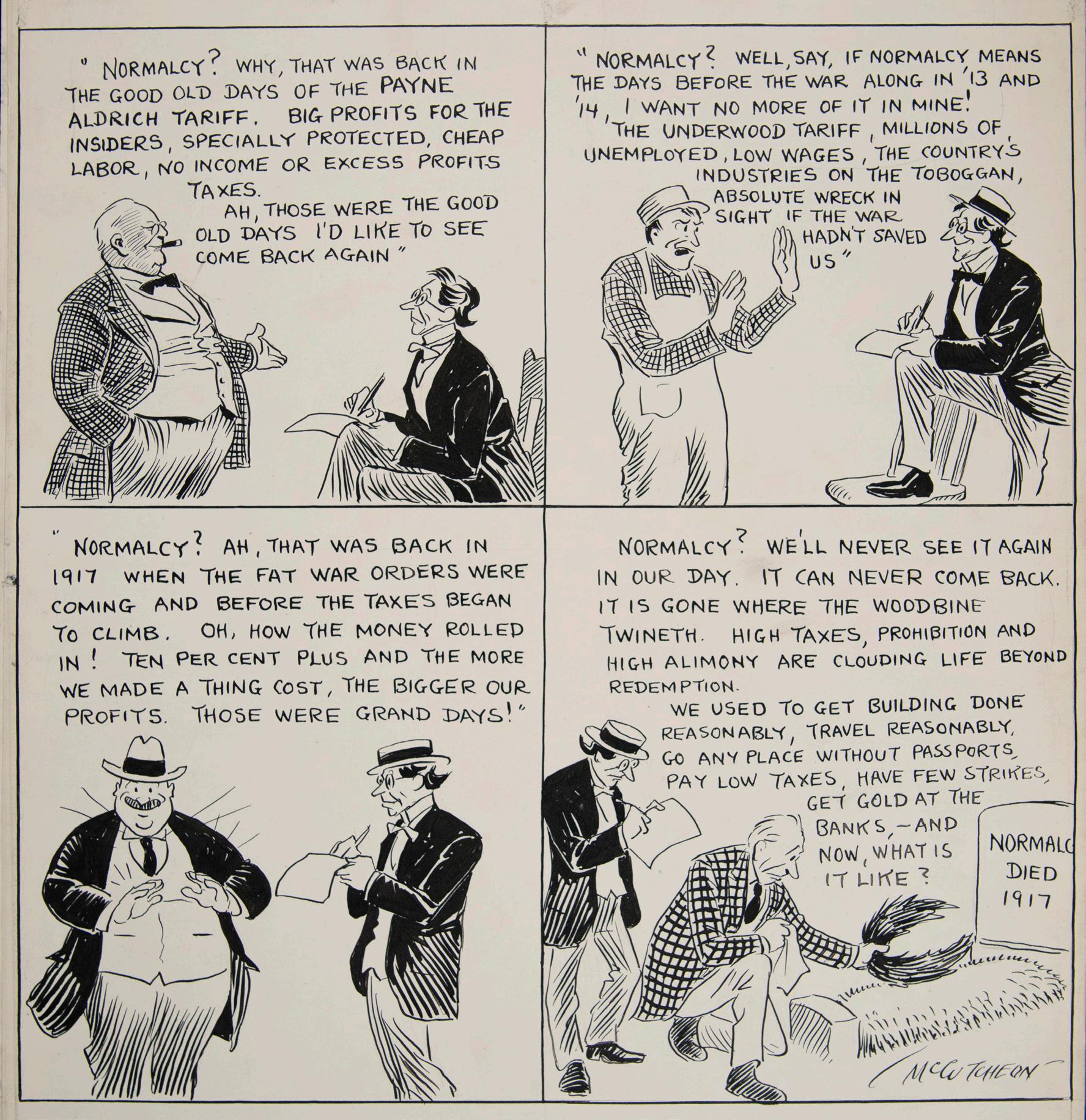

While campaigning for president, Harding promised Americans a “return to normalcy.” As this cartoon by the Chicago Tribune’s John T. McCutcheon implies, three months into the Harding Administration, Americans were still debating what was meant by this promise.

Warren G. Harding (the Republican candidate) and James M. Cox (the Democratic candidate) agreed on most major issues. Their differences came out in their campaign strategies.

Tapping into Americans’ anxieties about social change and civil unrest, Harding promised a “return to normalcy.” Cox, meanwhile, vowed to continue Woodrow Wilson’s ambitious policies that put the United States at the center of global politics.

Cox and his running mate, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, crisscrossed the country by rail to shore up support in states that Wilson had barely won in the 1916 election. Harding stayed home, giving speeches from his front porch in Marion, Ohio. But Harding’s folksy image belied the media-savvy tactics his campaign manager, Chicago advertising executive Albert Lasker, deployed on his behalf. Lasker ensured that Harding’s nostalgia-tinted campaign would achieve national exposure through mass media such as magazines, newsreels, and phonograph recordings.

In the end, Harding won the election with more than 60% of the vote—the largest margin of victory since James Monroe ran unopposed in 1820.

Paul Durica is Director of Exhibitions and Alex Teller is Director of Communications and Editorial Services at the Newberry.