10 minute read

Judging a Book by Its Cover

Judging a Book by Its Cover

Detail from George Salter's original cover illustration for Christopher Morley's "Ex Libris."

Advertisement

By Georgia Fowler

"Never judge a book by its cover,” we’re told. Whatever deep truths are hinted at in this old adage, it’s easier said than done when it comes to actual books and covers. Long after the plot lines and characters of a book disappear from memory, the cover design has a habit of lingering in our minds.

Resisting the temptation to judge a book by its cover is especially difficult when it comes to the work of George Salter (1897–1967), the German-born and—after 1940—American calligrapher, illustrator, teacher, and designer. A prolific jacket designer capable of capturing the essence of a book on its cover, Salter revolutionized book jacket design, fundamentally altering the way this art form was understood—and establishing jacket designers as artists in their own right.

"Of Mice and Men" cover illustration screen printed by Salter on book cloth.

The Newberry Library holds 66 boxes of Salter’s papers and artwork, a generous gift of the artist’s wife, Agnes Salter, and his daughter, Janet Salter Rosenberg.

The George Salter Papers include correspondence, notes, and articles written by and about Salter, but the vast majority of the material comprises his book jacket artwork.

Alongside sketches and prints for multiple German and American design jobs, the collection contains several books and the jackets he designed for them. Spanning approximately 95 linear feet, the Salter collection houses a wealth of beautiful work.

I can attest to this beauty myself. This past summer, I worked as an intern at the Newberry, fulfilling a practicum requirement for my Book Studies Concentration at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, where I am now a senior majoring in history.

My work at the Newberry focused on producing a finding aid for the Salter Papers. Though a paper finding aid was created in 1997, it was never digitized, so my job was to reorganize the collection and create a new digital aid that users could consult online to search and navigate the archive. Because I had created such tools before, the task was not particularly daunting. I was unprepared, however, for how attached I would become to the collection.

I was also surprised to find that scholars have paid little attention to Salter. His work is relevant to many areas, including art and design history, media studies, and literature.

Yet aside from a definitive biography, Classic Book Jackets: The Design Legacy of George Salter, by Wellesley professor Thomas S. Hansen, very little has been written about Salter. (I draw on Hansen’s work throughout this article.) This is an especially surprising omission given Salter’s fascinating life and his transformative impact on the world of jacket design.

George Salter, 1949

"Georg Salter” was born on October 5, 1897, in Bremen, Germany, to Stefanie (née Klein) and Norbert Salter. His parents, both born Jewish, converted to Lutheranism prior to his birth. The Salters were a musical family, and contact with many famous musicians and conductors led to Georg’s interest in stage and set design, the fields in which he initially trained.

Georg received only “satisfactory” marks in penmanship during his first years in school because he was left-handed and had to teach himself to write and draw right-handed (something he later encouraged left-handed students to do). His studies were put on hold after he completed secondary school in 1916 and, in the midst of World War I, joined the German Army—for which, along with other duties, he was a mapmaker (a task that augmented his skill as a draftsman).

Upon returning to civilian life in 1919, he began studying art with Ewald Dühlberg and enrolled in the Kunstgewerbeund Handwekerschule (School of Applied Arts and Crafts) in Berlin, where he studied under Harold Bengen and concentrated on scene painting. From 1921 to 1922, he worked at the Prussian State Opera in the studio for stage design and began to dedicate himself to professional theatrical design.

Yet during this period, Georg’s interests began to move from theatrical to book design. Soon, much of his professional attention was directed to the book arts. Between 1922 and 1934, he worked for 33 different German publishers and produced more than 350 designs, most of them for book jackets.

In his early years as a book designer— until around 1924—his style was expressionistic. But as he gained experience, Salter embraced a number of different design models, and his style became a hybrid modernism that incorporated both classical elements (particularly regarding calligraphy) and modern elements (evident especially in his color choices and renderings). His jackets thus often blended typographical innovation and symbolic illustration that allowed him to graphically convey a sense of the book’s contents.

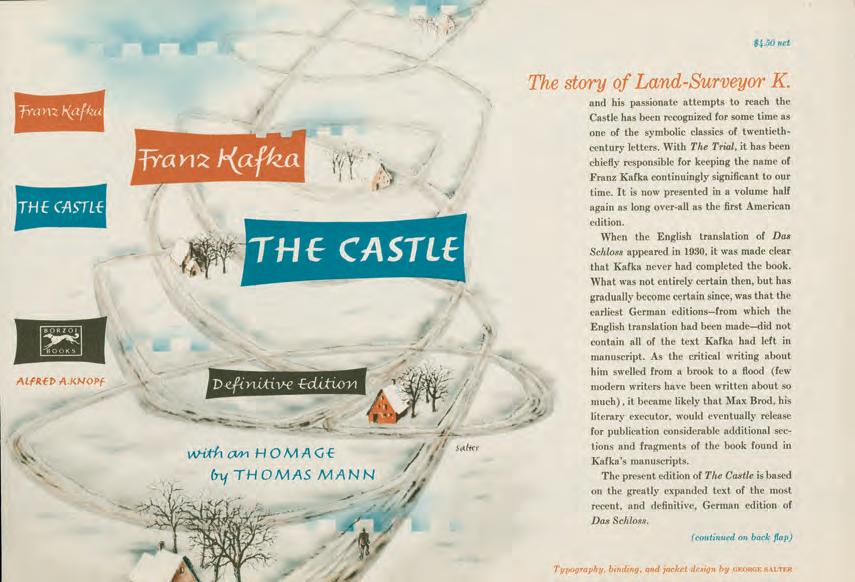

Salter's unique design style is exemplified in his book jacket for Franz Kafka's "The Castle" (1954).

Salter stood out from his contemporaries, whose art nouveau aesthetic dominated the book market in the early twentieth century.

In 1931, Salter was hired by typographer Georg Trump to serve as the director of the Commercial Art Department at the Höhere Graphische Fachschule (Institute of Graphic Arts) in Berlin. There, Salter grew to enjoy teaching, but his opportunities were short-lived.

Soon after Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933, a student wearing a National Socialist uniform and carrying a knife accosted Salter, challenging Salter’s presence at the school based on his family’s Jewish background. The experience shook Salter to his core. Soon after, the Nazi regime forced Trump to dismiss Salter from his post at the school. (Trump, who did not support the Nazi Party, remained friends with Salter and soon left Berlin himself.)

Because Salter did not identify as Jewish, he had considered himself safe from persecution before this humiliation by a student. Wasting little time, he left Berlin and began to line up his affairs to emigrate to the United States. After acquiring an affidavit from his brother Stefan, who had emigrated years before, Salter received his visa from the consulate in Stuttgart on October 1, 1934. By early November, he had arrived in New York City.

Unlike many emigres to the United States in the 1930s, Salter did not suffer any long period of poverty or unemployment. His arrival had been anticipated by professionals in the New York book world, thanks to an exhibition of his work mounted at Columbia University in 1933 by Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt, who was the university’s curator of the Department of Rare Books.

Salter soon had commissions from Simon & Schuster and Viking Press. Through his work for Viking—and in particular his designs for books by Herman Broch and Stefan Zweig—he solidified his connections with German exile culture in New York City. In 1936, he designed his first Thomas Mann volume for Alfred A. Knopf, initiating a long and fruitful relationship with the publishing company.

Salter’s work for Knopf exemplified his unique style and the force of his impact on book jacket design. Knopf, who cared deeply about the appearance of his books, was especially attentive to his relationship with Salter, who in turn always worked closely with the art department at the publishing company.

Through his relationship with Knopf, Salter produced some of his greatest designs and arrived at the apex of his career. Between 1935 and 1967, Salter executed 178 jacket designs for Knopf, including designs for books by some of the most prominent Western writers of the day, including Kay Boyle, Albert Camus, Elias Canetti, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Paul Gallico, John Hersey, Franz Kafka, H. L. Mencken, and Robert Nathan.

Many of these covers displayed what became Salter’s distinctive style—an airbrushed and often minimalist aesthetic coupled with a burst of color.

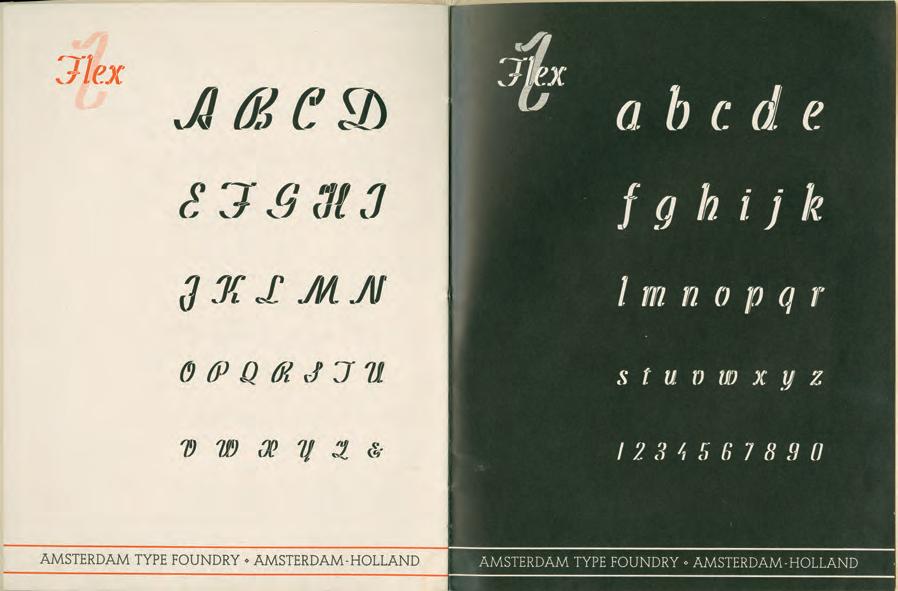

Salter remained keenly aware of the importance and role of typefaces in book production, and he even designed his own—“Flex”— a ribbon font named for its flowing, calligraphic lines. Meanwhile, in part because Knopf encouraged his designers to sign their work and mentioned them in colophons and advertisements, Salter signed his name to many of his jackets, marking them as his own.

Salter developed his own typeface—“Flex”—to use in his book jacket designs.

Perhaps most striking was Salter’s ability to capture the essence of a book on its cover, encouraging an immediate dialogue between designer and viewer. In many of his jacket designs for Knopf as well as other publishers, Salter incorporated symbolism to suggest historical relevance, lending his art a subtlety that was greatly admired by readers and publishers alike.

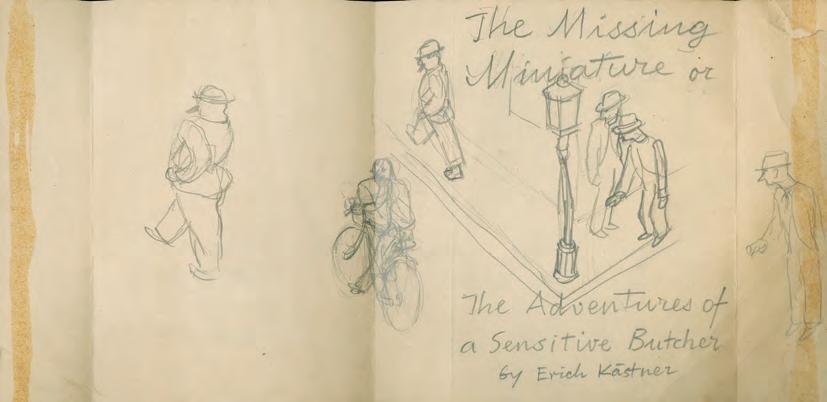

Salter’s ability to convey the sense of a book in a single striking image depended on his practice of reading almost every work for which he designed a jacket. The one exception was mysteries, which Salter did not enjoy reading. Instead, his wife, Agnes, would read and then summarize them for Salter, suggesting material that he could use in his jacket designs.

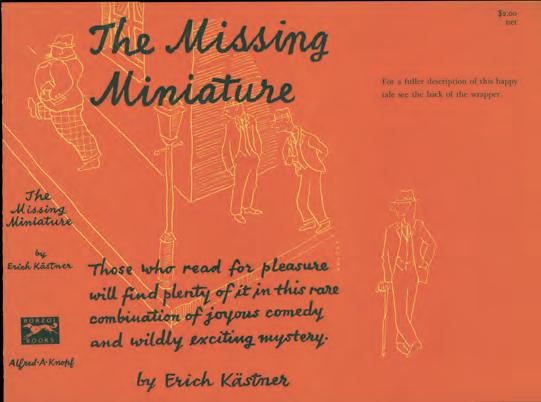

One of Salter’s initial designs for "The Missing Miniature"

Asketch for an alternative cover for "The Missing Miniature" drawn on the unfolded reverse side

A final printed version of the front and back covers of Salter’s jacket showing the revised title and implementation of the sketched design

Even as a new immigrant, Salter worked constantly. During his first six years in the United States, Salter produced some 185 book jackets and at least 30 magazine covers.

Meanwhile, he established himself as a preeminent book jacket designer for mysteries, which led to a long-lasting association with publisher Lawrence E. Spivak, who had a small empire in the world of mysteries and science fiction. At the same time, Salter formed attachments with American writers such as Nora Lofts, William Faulkner, and Frederic Prokosch.

On September 19, 1940, Georg Salter became George Salter, a naturalized American citizen. From that day on, he signed his name only with the Anglicized spelling, “George.” (He left his colleagues bemused because he enjoyed paying taxes, which he viewed as a symbol of belonging in his new country.) In 1942, he married Agnes Veronica O’Shea (1901–1989) after a two-year-long friendship. A few years later, in 1946, the couple adopted their daughter, Janet Salter Rosenberg. The family lived in Greenwich Village.

By 1950, Salter had risen to the top of his profession. Even during a dry spell in the mid-1950s, his colleagues still greatly respected him and publishers coveted his jackets. Many of his designs from this period became signature pieces for seminal literary works of the twentieth century, including William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

His success was also demonstrated by his election in 1947 as chairman of the Book Jacket Designers Guild—a group dedicated to encouraging interest in the book jacket as a form of art—and his election to membership in the Grolier Club, a prestigious New York bibliophilic group, in 1951.

As mass market forces and cheap production techniques led to a decline in the quality of book jacket design and a lowering of artistic standards, Salter worked to redefine the book jacket as a form of art. Though he was by no means alone in this effort, his prominence in the publishing world and his dedication as an artist exerted a powerful impact. He valued the craftsmanship that went into creating book jackets and influenced his colleagues and students to take similar care.

And as the first designer to sign his name to his covers, he stamped his work as art rather than simply the protective shell of a book. George Salter passed away on October 31, 1967, in New York City. He and Agnes are both buried in Cummington, Massachusetts, where the family had at one time summered. He remains one of the seminal calligraphers, book and book jacket designers, and illustrators of the twentieth century.

Renewed scholarly engagement with Salter is long overdue. As the home of the George Salter Papers, the Newberry is the best place to start. The first six boxes of the collection house a broad range of personal papers and articles, including a selection of correspondence, notes from classes and lectures given by Salter, and articles he published.

The remaining 60 or so boxes contain artwork from his design jobs, both in Germany and the United States. There are pen trials, sketches, prints, and original paintings. A few projects even include correspondence he exchanged with other designers or contributors. For example, the collection includes a letter from Salvador Dali’s wife, Gala, concerning work Salter completed for an edition of Cervantes’s Don Quixote that included illustrations by Dali. Finding gems like this letter throughout the collection made my summer internship at the Newberry especially rewarding and exciting.

I plan to continue using the Salter collection in my own scholarship at Smith, as I undertake a joint senior thesis and capstone on German book artists who were forced to flee Nazi Germany in the early 1930s. I will focus both on George Salter and Elizabeth Friedlander, another German designer and calligrapher. With luck, my research for the Salter portion of this project will bring me back to the Newberry in less than a year’s time.

Though I was sorry to leave the Newberry at the end of the summer, I am encouraged to know that George Salter and his wonderful designs will be here to greet me upon my return. Until then, I will browse used book stores, always on the lookout for what are certainly some of the most distinctive book jackets of the twentieth century.

[Georgia Fowler, former intern at the Newberry, is a senior at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.]