9 minute read

Teaching History through Poetry

How one English Language Arts teacher uses the Newberry’s Digital Collections for the Classroom to teach the 1919 Chicago race riots

Advertisement

By Kara Johnson

“What caused the race riots in Chicago on July 27, 1919?” “What were the Chicago stockyards?” “Why does racism still occur?”

These questions appear on Post-It notes on the walls of Valerie Person’s sophomore English Language Arts class at Currituck County High School in North Carolina. Person’s students are starting a new chapter in their class: a unit on the 1919 race riots in Chicago. And they’ve asked these questions to guide their work.

These sophomores are looking to sources across the humanities, analyzing historical documents alongside works of fiction and poetry related to the race riots. Person knows that

What were the Chicago stockyards?

Why does racism still occur?

her experimental, interdisciplinary class challenges expectations, and she relishes being able to respond to questions about her approach. She says with a laugh, “I learned early on in my career that it was a good thing when I was asked questions like, Why are we doing history in English class?”

Person has been an active participant at the Newberry, including taking part in Reading Material Maps in the Digital Age, a 2018 National Endowment for the Humanities summer

seminar for K-12 teachers held at the library.

During that seminar, she explored the intersections between technology and traditional cartography, the decisions that go into creating and producing maps, and the role of “place” in making and reading literature. She learned techniques for teaching with maps, while also cultivating her interest in how geography affects one’s interpretation of literature— including poetry.

Her passion for poetry in particular recently brought Person back to the Newberry— virtually, this time. After reading Eve Ewing’s acclaimed poetry collection, 1919 (published in 2019), Person followed a path of literary and historical discovery Published in 1922, The Negro in Chicago reported on the causes of the 1919 Chicago race riots.

that eventually led her to the library’s suite of digital resources for teachers. “Marriage and Family in Shakespeare’s England,” among many

Ewing’s poems reflect on the violence that erupted in others. These digital collections have been viewed more than Chicago in the summer of 1919, after an African American 300,000 times. In 2018, nearly 200,000 users from all over the teenager named Eugene Williams was murdered at a segregated world visited the website. beach on Lake Michigan. As she explained at a Newberry public program this past autumn, Ewing—an assistant professor in the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration P erson wholeheartedly subscribes to a philosophy and Twitter movement known as #TeachLivingPoets, which and acclaimed author, poet, and visual artist—was inspired to encourages using the work of contemporary poets in the write 1919 after reading The Negro in Chicago (1922), a lengthy classroom to make poetry more accessible and relatable for report by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations, a young adults. She constantly questions which writers are being committee charged with investigating the cultural, social, and taught and asks why, in ways that she hopes will empower economic factors that led to the 1919 riots. students to do the same.

Person wanted to teach 1919 in her class. And she also In addition to diversifying her syllabus, Person teaches wanted to guide her students to learn more about Ewing’s literature through an interdisciplinary lens, especially by source material and other primary source documents about the incorporating historical documents into her poetry units. In the riots. To do so, she turned to the Newberry’s Digital Collections process, Person often invites her students to “unlearn” deeply for the Classroom (DCC), an online resource featuring highingrained ideas about how humanities disciplines should be kept quality digital images of primary sources held at the Newberry, separate from one another. content-based essays by subject experts, discussion questions, She explains, “A lot of times my students come to me and supplemental K-12 classroom activities and lesson plans. with a very defined idea of what an English class should look Supported by The Grainger Foundation, the Newberry’s like. My class does not look like that very often, and so they DCC includes resources for teachers on nearly 100 different question it. Some are resistant to combining history and humanities subjects, and it is still growing. literature in the same class, because by the time they get to

Topics include “World War II and American Visual high school, they’ve been exposed so much to the idea that Culture,” “Flappers, G-Men, and Prohibition Legacies,” and these subjects should be distinct.”

A poem from 1919 about Emmett Till—a Chicago-born African American teenager who was lynched in 1955 while visiting relatives in Mississippi—demonstrated the value of learning historical context alongside poetry, while leaving an indelible impression on the students. Person says that prior to reading 1919, her students had never heard of Till. By the end of the unit, they were moved by the way that Till’s death illuminates an uglier side of America’s past—and present— that everyone should know. Her students encouraged her to continue to teach this tragic moment in American history to future classes.

To contextualize Ewing’s poetic interpretations of the 1919 race riots, Person relied on the historical sources on the Newberry’s DCC platform. She consulted the Newberry’s “1919 Race Riots” digital collection, written by Dr. Megan Geigner, an Assistant Professor of Instruction in Theatre and Drama at Northwestern University. This particular DCC describes in detail the events and aftermath of the race riots, as well as the representations of the violence in multiple media, including newspapers, photography, cartoons, pamphlets, and maps. The sources in the collection perfectly complemented Person’s 1919 poetry unit.

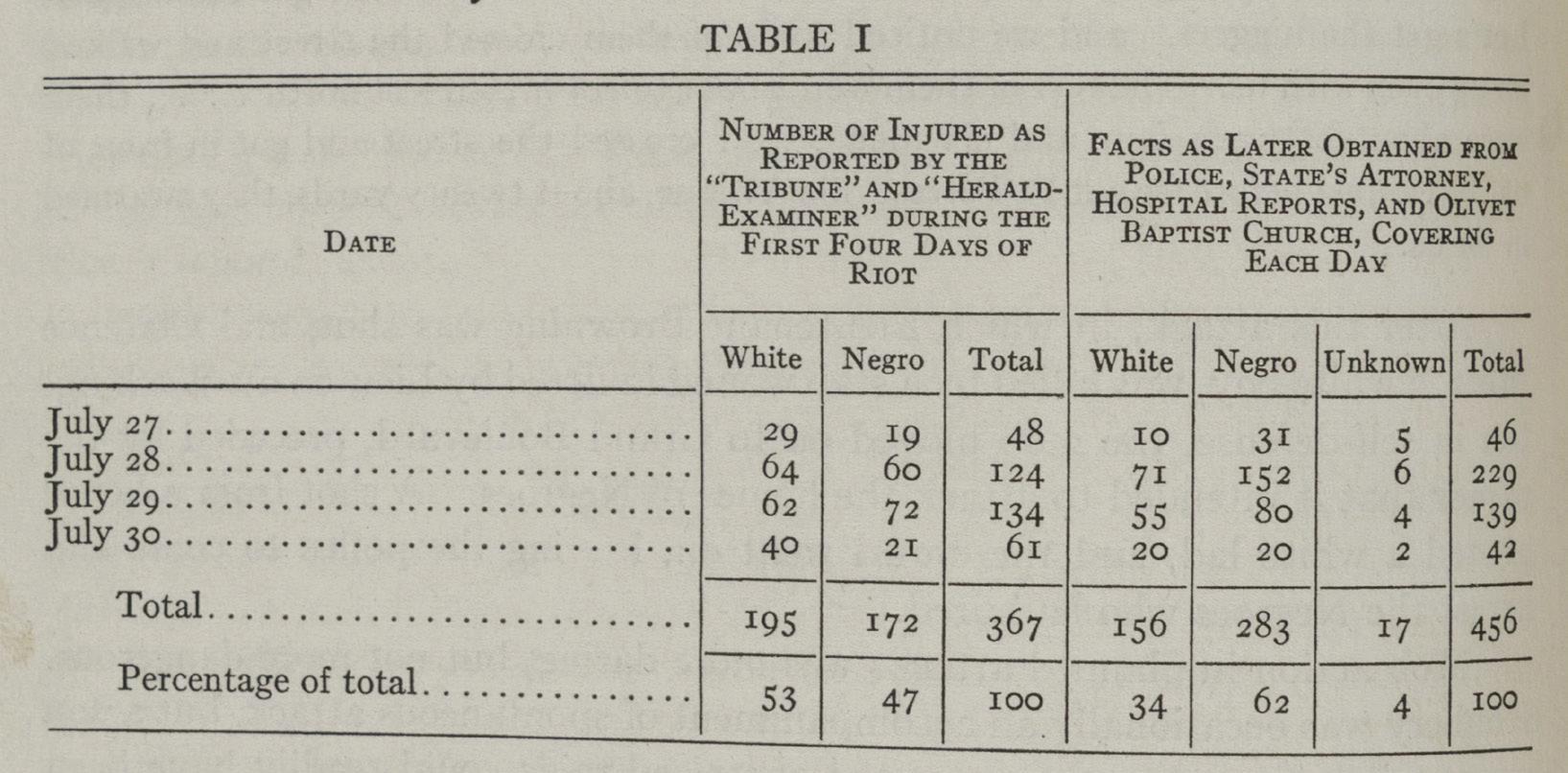

Person says the DCC helped her achieve two goals: filling gaps in historical knowledge and context and answering some of the questions that Ewing’s provocative text had generated among her students. The diverse range of digitized materials featured in the DCC provided powerful visual representations of the emotionally evocative scenes depicted in Ewing’s poems. One particular document, a page from the Chicago Tribune listing the dead and injured in the race riots, demonstrated the importance of humanizing the people affected by the riots. When placed alongside other items in the DCC, which include anonymous statistics of the injured or dead, this list encouraged students to look beyond statistics and consider human experience.

Eve Ewing’s latest book of poetry, 1919, inspired Person to teach the 1919 Chicago race riots through both literary and historical sources. Photo by Sara Allman

“It’s very easy to get caught up with the data, the numbers,” says Person. “But what we worked hard on is recognizing the individual names and the stories behind them.” Her students certainly responded to that idea. She describes overhearing students commenting to each other with remarks like, “Writing their names, that is humanizing them. These are human beings.”

Person’s course design, Ewing’s poetry, and the DCC all center African American experiences. Consequently, they destabilize one persistent—and inaccurate—historical explanation of the race riots: that white immigrant workingclass Chicagoans felt threatened as a result of African Americans arriving in the North during the Great Migration. According to Geigner, this explanation too often functions as an apology for white supremacy, and fails to account for migrants’ individual experiences.

Exploring the murder of Eugene Williams and the violence that erupted and spread across Chicago in 1919 enabled Person to teach her students about “the roles of perpetrator and bystander.” She asked students to think about the past on a personal level, inviting them to consider what they would have

This map from The Negro in Chicago is featured on the Newberry’s Digital Collections for the Classroom platform.

done if they were placed in a certain situation. Many students were shocked by the bystanders who did not help Williams as he was drowning after being struck with a rock. According to Person, the students asked: “‘How could people witness what happened on that beach initially, and not stand up for what was right?’ It was shocking to them.”

Successful teaching, Person recognizes, requires activating students to learn to their fullest potential. She explains that students in her Language Arts class are exceptional, because they all “come in every day hungry to learn and soak everything up like sponges.” This hunger for learning is fed by Person’s experience with digital learning and her creative, interdisciplinary approach to teaching literature. When teachers adopt an interdisciplinary, student-based model like Person’s, students become more active in making their own connections across topics and primary sources.

For instance, the unit on the race riots prompted some students to bring their own family histories into the class. During a discussion of the Great Migration, one student mentioned that his great-grandmother had migrated from Mississippi to Chicago and was living in the city during the 1919 race riots. He learned about her experiences before she passed away, and still visits relatives in Chicago occasionally. That he was able to share that part of his life with the rest of the class “was particularly meaningful to him,” Person notes.

As Person’s wonderful combination of teaching strategies, primary sources, and creative interpretations of historical events demonstrates, studying the humanities is so much more than memorizing names, places, and dates.

“If I could give a student one quality, before they walk into the classroom, it’s intellectual curiosity—that hungry curiosity,” she says. “If they have that, it makes what we as teachers do not only delightful—it makes it a lot easier. You can teach the skills, but if they have the curiosity, that’s a win-win.” Person’s investment in her students, provocative teaching approaches, and welcoming and open classroom environment will allow her students to reap the rewards of that curiosity for years to come.

Kara Johnson is Manager of Teacher and Student Programs at the Newberry.

The Newberry Library takes pride in supporting teachers and students across the country and the world. One critical way we extend our reach beyond the library’s walls is through digital resources like Digital Collections for the Classroom.

For more information on Digital Collections for the Classroom, please visit dcc.newberry.org.

A table from The Negro in Chicago shows the actual number of deaths and injuries caused by the riots––as compared to the numbers reported during the riots. Available on Digital Collections for the Classroom.

Three days after the conflict began, Chicago was still reeling from violence as depicted in these photographs from the Chicago Daily Tribune.