2

Paying for Health Care

Health care is not free. Someone must pay. But how? Does each person pay when receiving care? Do people contribute regular amounts in advance so that their care will be paid for when they need it? When a person contributes in advance, might the contribution be used for care given to someone else? If so, who should pay how much?

Health care financing in the United States evolved to its current state through a series of social interventions. Each intervention solved a problem but in turn created its own problems requiring further intervention. This chapter will discuss the historical process of the evolution of health care financing. The enactment in 2010 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, commonly referred to as the Affordable Care Act, ACA, or “Obamacare,” created major changes in the financing of health care in the United States.

MODES OF PAYING FOR HEALTH CARE

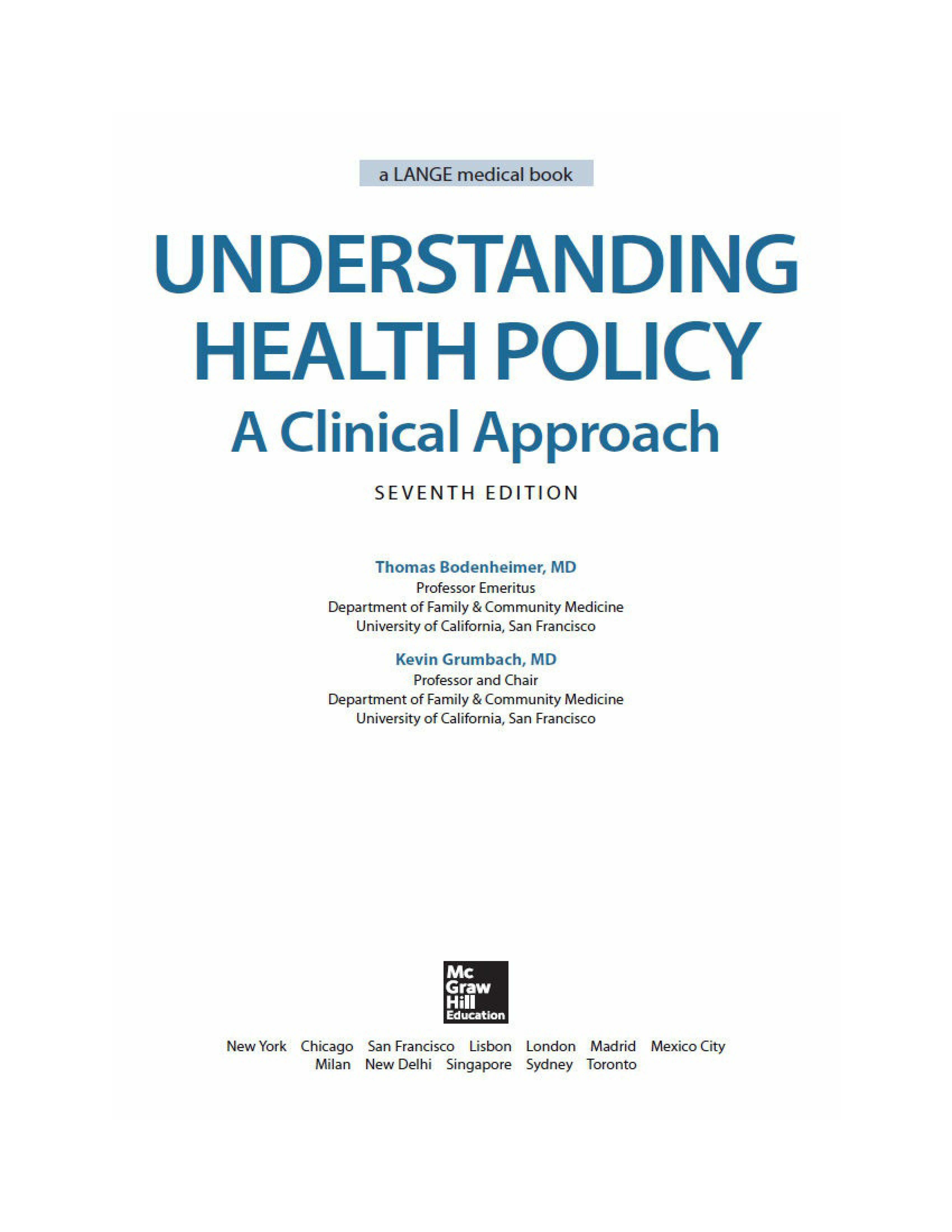

The four basic modes of paying for health care are out-of-pocket payment, individual private insurance, employment-based group private insurance, and government financing (Table 2–1). These four modes can be viewed both as a historical progression and as a categorization of current health care financing.

Table 2–1. Health care financing in 2013a

Type of Payment

Out-of-pocket payment

lnd : ividual private ins urance

Employment-based private insurance

Government finandng

Other

Total

Principal Source ,of Coverage

Un insured

lnd iividual1private insurance

Employment-ba.sed private insurance

Government fin ancirng

Total

These figur es precede implementation of most of the Affordable Care Act.

Source: Data extracted from Hartm,an Met al. National heafth spending in 2013: growth sl1ows, remains in step wrth the overall econom y. Health Aff 2015 ;34: 150- 160; US C ens us Bureau: Hea Ith Insu ranee Coverage ln the United States, 2013. September; 2014.

0 Because private ins urance te nds to cover healthier people~the percentage of expe nditures [s far less t han the percentage of population covered. Pub l1ic expendrtures are far higher per popu ation because t he elderly and disab ed are concentrated in the public Medicare and Med i caid programs.

tJ-rhis includes private insurance obtained by federat state, and local emp iloyees which is in part purchased by tax funds.

Out-of-Pocket Payments

Fred Farmer broke his leg in 1913. His son ran 4 miles to get the doctor, who came to the farm to splint the leg. Fred gave the doctor a couple of chickens to pay for the visit. His great-grandson, Ted, who is uninsured, broke his leg in 2013. He was driven to the emergency room, where the physician ordered an x-ray and called in an orthopedist who placed a cast on the leg. The cost was $2,800.

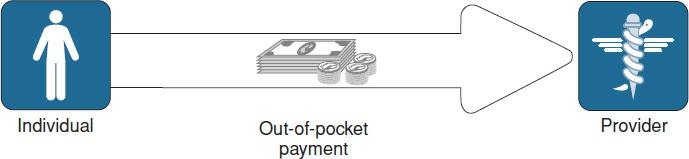

One hundred years ago, people like Fred Farmer paid physicians and other health care practitioners in cash or through barter. In the first half of the twentieth century, out-of-pocket cash payment was the most common method of payment. This is the simplest mode of financing—direct purchase by the consumer of goods and services (Fig. 2–1).

Figure 2–1. Out-of-pocket payment is made directly from patient to provider.

People in the United States purchase most consumer items and services, from gourmet restaurant dinners to haircuts, through direct out-of-pocket payments. This is not the case with health care (Arrow, 1963; Evans, 1984), and one may ask why health care is not considered a typical consumer item.

Need Versus Luxury

Whereas a gourmet dinner is a luxury, health care is regarded as a basic human need by most people.

For 2 weeks, Marina Perez has had vaginal bleeding and has felt dizzy. She has no insurance and is terrified that medical care might eat up her $500 in savings. She scrapes together $100 to see her doctor, who finds

that her blood pressure falls to 90/50 mm Hg upon standing and that her hematocrit is 26%. The doctor calls Marina’s sister Juanita to drive her to the hospital. Marina gets into the car and tells Juanita to take her home.

If health care is a basic human right, then people who are unable to afford health care must have a payment mechanism available that is not reliant on out-of-pocket payments.

Unpredictability of Need and Cost

Whereas the purchase of a gourmet meal is a matter of choice and the price is shown to the buyer, the need for and cost of health care services are unpredictable. Most people do not know if or when they may become severely ill or injured or what the cost of care will be.

Jake has a headache and visits the doctor, but he does not know whether the headache will cost $100 for a physician visit plus the price of a bottle of ibuprofen, $1,200 for an MRI, or $200,000 for surgery and irradiation for brain cancer.

The unpredictability of many health care needs makes it difficult to plan for these expenses. The medical costs associated with serious illness or injury usually exceed a middle-class family’s savings.

Patients Need to Rely on Physician Recommendations

Unlike the purchaser of a gourmet meal, a person in need of health care may have little knowledge of what he or she is buying at the time when care is needed.

Jenny develops acute abdominal pain and goes to the hospital to purchase a remedy for her pain. The physician tells her that she has acute cholecystitis or a perforated ulcer and recommends hospitalization, an abdominal CT scan, and upper endoscopic studies. Will Jenny, lying on a gurney in the emergency room and clutching her abdomen with one hand, use her other hand to leaf through a textbook of internal medicine to determine whether she really needs these services, and should she have brought along a copy of Consumer Reports to learn where to purchase them at the cheapest price?

Health care is the foremost example of asymmetry of information between providers and consumers (Evans, 1984). A patient with abdominal pain is in a poor position to question a physician who is ordering laboratory tests, x-rays, or surgery. When health care is elective, patients can weigh the pros and cons of different treatment options, but even so, recommendations may be filtered through the biases of the physician providing the information. Compared with the voluntary demand for gourmet meals, the demand for health services is partially involuntary and is often physician rather than consumer-driven.

For these reasons among others, out-of-pocket payments are flawed as a dominant method of paying for health care services. Because the direct purchase of health services became increasingly difficult for consumers and was not meeting the needs of hospitals and physicians to be reliably paid, health insurance came into being.

Individual Private Insurance

In 2012, Bud Carpenter was self-employed. To pay the $500 monthly premium for his individual health insurance policy, he had to work extra jobs on weekends, and the $5,000 deductible meant he would still have to pay quite a bit of his family’s medical costs out of pocket. Mr. Carpenter preferred to pay these costs rather than take the risk of spending the money saved for his children’s college education on a major illness. When he became ill with leukemia and the hospital bill reached $80,000, Mr. Carpenter appreciated the value of health insurance. Nonetheless he had to feel disgruntled when he read a newspaper story listing his insurance company among those that paid out on average less than 60 cents for health services for every dollar collected in premiums.

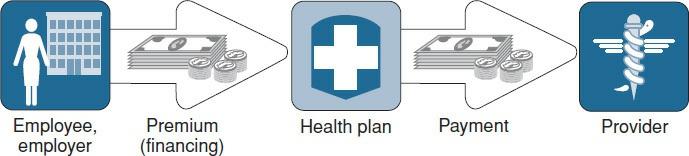

With private health insurance, a third party, the insurer is added to the patient and the health care provider, who are the two basic parties of the health care transaction. While the out-of-pocket mode of payment is limited to a single financial transaction, private insurance requires two transactions— a premium payment from the individual to an insurance plan (also called a health plan), and a payment from the insurance plan to the provider (Fig. 2–2). In nineteenth-century Europe, voluntary benefit funds were set up by guilds, industries, and mutual societies. In return for paying a monthly sum, people received assistance in case of illness. This early form of private health

insurance was slow to develop in the United States. In the early twentieth century, European immigrants set up some small benevolent societies in US cities to provide sickness benefits for their members. During the same period, two commercial insurance companies, Metropolitan Life and Prudential, collected 10 to 25 cents per week from workers for life insurance policies that also paid for funerals and the expenses of a final illness. The policies were paid for by individuals on a weekly basis, so large numbers of insurance agents had to visit their clients to collect the premiums as soon after payday as possible. Because of the huge administrative costs, individual health insurance never became a dominant method of paying for health care (Starr, 1982). In 2013, prior to the implementation of the individual insurance mandate of the ACA, individual policies provided health insurance for 7% of the US population (Table 2–1).

Figure 2–2. Individual private insurance. A third party, the insurance plan (health plan), is added, dividing payment into a financing component and a payment component. The ACA added an individual coverage mandate for those not otherwise insured and federal subsidy to help individuals pay the insurance premium.

In 2014, Bud Carpenter signed up for individual insurance for his family of 4 through Covered California, the state exchange set up under the ACA. Because his family income was 200% of the federal poverty level, he received a subsidy of $1,373 per month, meaning that his premium would be $252 per month (down from his previous monthly premium of $500) for a silver plan with Kaiser Permanente. His deductible was $2,000 (down from $5,000). Insurance companies were no longer allowed to deny coverage for his pre-existing leukemia.

The ACA has many provisions, described in detail in the Kaiser Family Foundation (2013a) Summary of the Affordable Care Act and discussed more in Chapter 15. One of the main provisions is a requirement (called the “individual mandate”) that most US citizens and legal residents who do not have governmental or private health insurance purchase a private health

Individual Prem ium (financi ng )

He aJlt h pllan Paymem P rovide r

insurance policy through a federal or state health insurance exchange, with federal subsidies for individual and families with incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level ($24,250 to $97,000 for a family of four). Details of the individual mandate are provided in Table 2–2.

Table 2–2. Summary of the Individual Mandate Provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), 2015

U.S. citizens and legal residents are required to have health coverage with exemptions available for such issues as financial hardship. Those who choose to go without coverage pay a tax penalty of $325 or 2% of taxable income in 2015, which gradually increases over the years. People with employer-based and governmental health insurance are not required to purchase the insurance required under the individual mandate.

Tax credits to help pay health insurance premiums increase in size as family incomes rise from 100% to 400% of the Federal Poverty Level. In addition subsidies reduce the amount of out-of-pocket costs individuals and families must pay; the amount of the subsidy varies by income.

Under the individual mandate, health insurance is purchased though insurance marketplaces called health insurance exchanges. Seventeen states have elected to set up their own exchanges; the remainder of states are covered by the federal exchange, Healthcare.gov.

Insurance companies marketing their plans through the exchanges offer four benefit categories:

• Bronze plans represent minimum coverage, with the insurer paying for 60% of a person’s health care costs, with high out-of-pocket costs but low premiums

• Silver plans cover 70% of health care costs, with fewer out-of-pocket costs and higher premiums

• Gold plans cover 80% of costs, with low out-of-pocket costs and high premiums

• Platinum plans cover 90% of costs, with very low out-of-pocket costs and very high premiums

Most people who have obtained insurance through the exchanges have picked Bronze or Silver plans, and 87% have received a subsidy. A

family of four with income at 150% of the federal poverty level receives an average subsidy of $11,000. At 300% of the federal poverty level the subsidy is about $6,000.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation. Summary of the Affordable Care Act. 2013. http://kff.org/healthreform/fact-sheet/summary-of-the-affordable-care-act. Accessed March 12, 2015.

Employment-Based Private Insurance

Betty Lerner and her schoolteacher colleagues each paid $6 per year to Prepaid Hospital in 1929. Ms. Lerner suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized at no cost. The following year Prepaid Hospital built a new wing and raised the teachers’ prepayment to $12.

Rose Riveter retired in 1961. Her health insurance premium for hospital and physician care, formerly paid by her employer, had been $25 per month. When she called the insurance company to obtain individual coverage, she was told that premiums at age 65 cost $70 per month. She could not afford the insurance and wondered what would happen if she became ill.

The development of private health insurance in the United States was impelled by the increasing effectiveness and rising costs of hospital care. Hospitals became places not only in which to die, but also in which to get well. However, many patients were unable to pay for hospital care, and this meant that hospitals were unable to attract “customers.”

In 1929, Baylor University Hospital agreed to provide up to 21 days of hospital care to 1,500 Dallas schoolteachers such as Betty Lerner if they paid the hospital $6 per person per year. As the Great Depression deepened and private hospital occupancy in 1931 fell to 62%, similar hospital-centered private insurance plans spread. These plans (anticipating health maintenance organizations [HMOs]) restricted care to a particular hospital. The American Hospital Association built on this prepayment movement and established statewide Blue Cross hospital insurance plans allowing free choice of hospital. By 1940, 39 Blue Cross plans controlled by the private hospital industry had enrolled over 6 million people. The Great Depression reduced the amount patients could pay physicians out of pocket, and in 1939, the California Medical Association set up the first Blue Shield plan to cover physician services. These plans, controlled by state medical societies,

followed Blue Cross in spreading across the nation (Starr, 1982; Fein, 1986).

In contrast to the consumer-driven development of health insurance in European nations, coverage in the United States was initiated by health care providers seeking a steady source of income. Hospital and physician control over the “Blues,” a major sector of the health insurance industry, guaranteed that payment would be generous and that cost control would remain on the back burner (Law, 1974; Starr, 1982).

The rapid growth of employment-based private insurance was spurred by an accident of history. During World War II, wage and price controls prevented companies from granting wage increases, but allowed the growth of fringe benefits. With a labor shortage, companies competing for workers began to offer health insurance to employees such as Rose Riveter as a fringe benefit. After the war, unions picked up on this trend and negotiated for health benefits. The results were dramatic: Enrollment in group hospital insurance plans grew from 12 million in 1940 to 142 million in 1988.

With employment-based health insurance, employers usually pay much of the premium that purchases health insurance for their employees (Fig. 2–3). However, this flow of money is not as simple as it looks. The federal government views employer premium payments as a tax-deductible business expense. The government does not treat the health insurance fringe benefit as taxable income to the employee, even though the payment of premiums could be interpreted as a form of employee income. Because each premium dollar of employer-sponsored health insurance results in a reduction in taxes collected, the government is in essence subsidizing employer-sponsored health insurance. This subsidy is enormous, estimated at $250 billion per year (Ray et al., 2014).

Figure 2–3. Employment-based private insurance. In addition to the direct employer subsidy, indirect government subsidies occur through the tax-free status of employer contributions for health insurance benefits.

The ACA made a change in employer-based health insurance, requiring employers with 50 or more full-time employees to offer coverage or pay a fee to the government; the fee is meant to discourage employers from dropping employee health insurance, which they might be tempted to do since their employees could buy individual insurance through the health insurance exchanges (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013b).

The growth of employment-based health insurance attracted commercial insurance companies to the health care field to compete with the Blues for customers. The commercial insurers changed the entire dynamic of health insurance. The new dynamic was called experience rating. (The following discussion of experience rating can be applied to individual as well as employment-based private insurance.)

Healthy Insurance Company insures three groups of people a young healthy group of bank managers, an older healthy group of truck drivers, and an older group of coal miners with a high rate of chronic illness. Under experience rating, Healthy sets its premiums according to the experience of each group in using health services. Because the bank managers rarely use health care, each pays a premium of $300 per month. Because the truck drivers are older, their risk of illness is higher, and their premium is $500 per month. The miners, who have high rates of black lung disease, are charged a premium of $700 per month. The average premium income to Healthy is $500 per member per month.

Blue Cross insures the same three groups and needs the same $500 per member per month to cover health care plus administrative costs for these groups. Blue Cross sets its premiums by the principle of community rating. For a given health insurance policy, all subscribers in a community pay the same premium. The bank managers, truck drivers, and mine workers all pay $500 per month.

Health insurance provides a mechanism to distribute health care more in accordance with human need rather than exclusively on the basis of ability to pay. To achieve this goal, funds are redistributed from the healthy to the sick, a subsidy that helps pay the costs of those unable to purchase services on their own.

Community rating achieves this redistribution in two ways:

1. Within each group (bank managers, truck drivers, and mine workers), people who become ill receive benefits in excess of the premiums they pay, while people who remain healthy pay premiums while receiving few or no health benefits.

2. Among the three groups, the bank managers, who use less health care than their premiums are worth, help pay for the miners, who use more health care than their premiums could buy.

Experience rating is less redistributive than community rating. Within each group, those who become ill are subsidized by those who remain well, but among the different groups, healthier groups (bank managers) do not subsidize high-risk groups (mine workers). Thus the principle of health insurance, which is to distribute health care more in accordance with human need rather than exclusively on the ability to pay, is weakened by experience rating (Light, 1992).

In the early years, Blue Cross plans set insurance premiums by the principle of community rating, whereas commercial insurers used experience rating as a “weapon” to compete with the Blues (Fein, 1986). Commercial insurers such as Healthy Insurance Company could offer cheaper premiums to low-risk groups such as bank managers, who would naturally choose a Healthy commercial plan at $300 over a Blue Cross plan at $500. Experience rating helped commercial insurers overtake the Blues in the private health insurance market. While in 1945 commercial insurers had only 10 million enrollees, compared with 19 million for the Blues, by 1955 the score was commercials 54 million and the Blues 51 million.

Many commercial insurers would not market policies to such high-risk groups as mine workers, leaving Blue Cross with high-risk patients who were paying relatively low premiums. To survive the competition from the commercial insurers, Blue Cross had no choice but to seek younger, healthier groups by abandoning community rating and reducing the premiums for those groups. In this way, many Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans switched to experience rating. Without community rating, older and sicker groups became less and less able to afford health insurance.

From the perspective of the elderly and those with chronic illness, experience rating is discriminatory. Healthy persons, however, might have another viewpoint and might ask why they should voluntarily transfer their wealth to sicker people through the insurance subsidy. The answer lies in the

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Rosetter Gleason Cole (1866)

Some Opera Writers

I������

Claudio Merulo (1533–1604) (Madrigal Play)

Vincenzo Galilei (1533–1591)

Giulio Caccini (1546–1618)

Emilio del Cavalieri (1550–1602)

Jacopo Perti (1561–1633)

Claudio Monteverde (1567–1643)

Francesco Manelli (1595–1670)

Benedetto Ferrari (1597–1681)

Francesco Cavalli (1602–1676)

Giacomo Carissimi (1604–1674)

Marc Antonio Cesti (1620–1669)

Giovanni Legrenzi (1625–1690)

Domenico Gabrieli (1640–1690)

Alessandro Stradella (1645–1681)

Alessandro Scarlatti (1659–1725)

Jacopo Antonio Perti (1661–1756)

Attilio Ariosti (1666–1740)

Antonio Lotti (1667–1740)

Giuseppe Porsile (1672–1750)

Marc Antonio Buononcini (1675?–1726)

Antonio Caldara (1678?–1736)

Niccolo Antonio Porpora (1686–1766)

Leonardo Vinci (1690–1730)

Leonardo Leo (1694–1744)

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–1736)

Nicola Jommelli (1714–1774)

Nicolo Piccinni (1728–1800)

Giuseppe Sarti (1729–1802)

Antonio Sacchini (1734–1786)

Giovanni Paisiello (1741–1816)

Domenico Cimarosa (1749–1801)

Antonio Salieri (1750–1825)

Niccolo Vaccai (1790–1848)

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (1792–1868)

G. Saverio Mercadante (1795–1870)

Giovanni Pacini (1796–1867)

Gaetano Donizetti (1797–1848)

Vincenzo Bellini (1801–1835)

Errico Petrella (1813–1877)

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901)

Carlo Perdrotti (1817–1893)

Alberto Randegger (1833–1911)

Amilcare Ponchielli (1834–1886)

Filippo Marchetti (1835–1902)

Arrigo Boito (1842–1918)

Luigi Mancinelli (1848–1921)

Niccolo Ravera (1851)

Alfredo Catalani (1854–1893)

Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924)

Ruggiero Leoncavallo (1858–1919)

Sylvio Lazzari (1858) (Living in Paris)

Alberto Franchetti (1860)

Pietro Mascagni (1863)

Franco Leoni (1864)

Crescenzo Buongiorno (1864–1903)

Giacomo Orefice (1865–1923)

Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

Francesco Cilèa (1866)

Umberto Giordano (1867)

Giovanni Gianetti (1869)

Antonio Luzzi (1873)

Italo Montemezzi (1875)

Domenico Monleone (1875)

Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari (1876)

Franco Alfano (1877)

Stefano Donaudy (1879)

Ottorino Respighi (1879)

Alberto Iginio Randegger (Austrian) (1880–1918)

Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880)

G. Francesco Malipiero (1882)

Giuseppe Gino Marinuzzi (1882)

Riccardo Zandonai (1883)

Francesco Santoliquido (1883)

Adriano Lualdi (1887)

Vincenzo Davico (1889)

Ettore Lucatello (?)

Victor de Sabata (1892)

S������

Salvador Giner (1832–1911)

Felipe Pedrell (1841–1922)

Tomas Breton y Hernandez (1850)

Amedeo Vives (?)

Costa Nogueras (?)

Isaac Albeniz (1861–1909)

Enrique Granados (1867–1916)

Manuel de Falla (1876)

Joan Manen (1883)

Maria Rodrigo (1888)

S���� A������

Carlos Gomez (Brazilian) (1839–1896)

José Valle-Riestra (Peruvian) (1859)

Antonio Berutti (Argentine) (1862)

F�����

Robert Cambert (1628–1679) (Wrote with Perrin)

Jean Batiste Lully (Italian) (1632–1687)

Pascal Colasse (1649–1709)

Marin Marais (1656–1728)

André Campra (1660–1744)

André Destouches (1672–1749)

Jean Philippe Rameau (1683–1764)

Egidio Romualdo Duni (Italian) (1709–1775)

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778)

François André Danican Philidor (1726–1795)

Pierre Berton (1727–1780)

Pierre Alexandre Monsigny (1729–1817)

François Joseph Gossec (1743–1829)

André Ernest Modeste Grétry (1741–1813)

Luigi Cherubini (Italian) (1760–1842)

Jean François Lesueur (1760–1837)

Étienne Henri Méhul (1763–1822)

Gasparo Luigi Pacifico Spontini (Italian) (1774–1851)

François Adrien Boieldieu (1775–1834)

Nicolo Isouard (1775–1818)

Daniel François Esprit Auber (1782–1871)

Louis Joseph Ferdinand Hérold (1791–1833)

Jacques F. F. E. Halevy (1799–1862)

Adolphe Adam (1803–1856)

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869)

Napoleon Henri Reber (1807–1880)

Félicien C. David (1810–1876)

Ambroise Thomas (1811–1896)

Louis Lacombe (1818–1884)

Charles François Gounod (1818–1893)

Jacques Offenbach (German) (1819–1880)

Victor Massé (1822–1884)

Edouard Lalo (1823–1892)

Louis Ernest Reyer (1823–1909)

Florimond Ronger Hervé (1825–1892)

Alexandre Charles Lecocq (1832–1918)

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921)

Ernest Guiraud (American) (1837–1892) (Born in New Orleans)

Théodore Dubois (1837–1924)

Georges Bizet (1838–1875)

Clément P. Léo Délibes (1839–1891)

Félix Victorin de Joncières (1839–1903)

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841–1894)

Jules Massenet (1842–1912)

Emile Paladilhe (1844)

Joseph Arthur Coquard (1846–1910)

Robert Planquette (1848–1903)

Benjamin Godard (1849–1895)

Augusta Holmès (British) (1849–1903)

François Thomé (1850–1905)

Alexandre Georges (1850)

Vincent d’Indy (1851)

Hillemacher Frères (Brothers) Paul (1852) Lucien (1860–1909)

Raoul Pugno (1852–1914)

Andre Messager (1853)

Samuel A. Rousseau (1853–1904)

Ernest Chausson (1855–1899)

Alfred Bruneau (1857)

Georges Hüe (1858)

Gustave Charpentier (1860)

Gabriella Ferrari (1860)

Pierre de Bréville (1861)

Claude Achille Debussy (1862–1918)

Xavier Leroux (1863–1919)

Camille Erlanger (1863–1919)

Gabriel Pierné (1863)

Paul Vidal (1863)

Alfred Bachelet (1864)

Alberic Magnard (1865–1914)

Paul Dukas (1865)

Albert Roussel (1869)

Florent Schmitt (1870)

Henri Büsser (1872)

Deodat de Sévérac (1873–1921)

Henri Rabaud (1873)

Reynaldo Hahn (Venezuelan) (1874)

Max d’Ollone (1875)

Antoine Mariotte (1875)

Maurice Ravel (1875)

Raoul Laparra (1876)

Jean Nouguès (1876)

Henri Février (1876)

Louis Aubert (1877)

Gabriel Dupont (1878–1914)

Félix Fourdrain (1880–1924)

Albert Wolf

Roland Manuel (1891)

Arthur Honegger (1892)

Darius Milhaud (1892)

B������

André Ernest Modeste Grétry (1741–1813) (Lived in Paris)

François Auguste Gevaert (1828–1908)

Pierre Benoit (1834–1901)

Jan Blockx (1851–1912)

Edgar Tinel (1854–1912)

Valentin Neuville (1863)

Paul Gilson (1865)

Alfred Kaiser (1872)

Charles Radoux (1877)

Albert Dupuis (1877)

Joseph van der Meulen (?)

D����

Anton Berlijn (1817–1870)

Johan Wagenaar (1862)

Jan Brandt-Buys (1868)

Cornelis Dopper (1870)

Charles Grelinger (?)

S����

Emile Jacques-Dalcroze (1865)

Gustave Doret (1866)

Othmar Schoeck (1886)

G�����

Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672)

Johann Thiele (1646)

Johann Christoph Pepusch (1667–1752) (Lived in London)

Johann Conradi (1670?–?)

Reinhard Keiser (1674–1739)

Johann Mattheson (1681–1764)

George Frederick Handel (1685–1759)

Johann Adolph Hasse (1699–1783)

Karl Heinrich Graun (1701–1759)

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–1787)

Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804)

Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739–1799)

Abt (Georg Joseph) Vogler (1749–1814)

Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814)

Peter von Winter (1754–1825)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Joseph Weigl (1766–1846)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Christoph Ernst Friederich Weyse (Danish) (1774–1842)

Konradin Kreutzer (1780–1849)

Ludwig (Louis) Spohr (1784–1859)

Carl Maria von Weber (1786–1826)

Peter Joseph von Lindpainter (1791–1856)

Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791–1864) (Lived in Paris)

Heinrich Marschner (1795–1861)

Karl Gottlieb Reissiger (1798–1859)

Gustav Albert Lortzing (1801–1851)

Otto Nicolai (1810–1849)

Friedrich von Flotow (1812–1883)

Richard Wagner (1813–1883)

Franz von Suppé (Austrian) (1819–1895)

Peter Cornelius (1824–1874)

Felix Draeseke (1835–1913)

Max Zenger (1837–1911)

Hermann Goetz (1840–1876)

Victor Nessler (Alsatian) (1841–1890)

Heinrich Hofmann (1842–1902)

Ignaz Brüll (Austrian) (1846–1907)

August Bungert (1846–1915)

August Klughardt (1847–1902)

Cyril Kistler (1848–1907)

Ivan Knorr (1853–1916)

Engelbert Humperdinck (1854–1921)

Heinrich Zöllner (1854)

Paul Geisler (1856–1919)

Wilhelm Kienzl (1857)

Alexander von Fielitz (1860)

Maria Joseph Erb (Alsatian) (1860)

Emil Nikolaus Reznicek (Austrian) (1861)

Ludwig Thuille (1861–1907)

Hugo Kaun (1863)

Felix Weingartner (1863)

Richard Strauss (1864)

Waldemar von Bausznern (1866)

Max Schillings (1868)

Hans Pfitzner (1869)

Siegfried Wagner (1869)

Alexander von Zemlinsky (Austrian) (1872)

Leo Fall (Austrian) (1873–1925)

Paul Graner (1873)

Waldemar Wendland (1873)

Julius Bittner (1874)

Arnold Schoenberg (1874)

Joseph Gustav Mrazek (Austrian) (1878)

Franz Schreker (Austrian) (1878)

Edgar Istel (1880)

Walter Braunfels (1882)

Egon Wellesz (Austrian) (1885)

Alban Berg (Austrian) (1885)

Paul Hindemith (1895)

Erich Korngold (Austrian) (1897)

Karl Krafft-Lortzing (?–1923)

Ignatz Waghalter (20th Century)

C�����-S��������

Bedrich (Friedrich) Smetana (1824–1884)

Eduard Napravnik (1839–1916)

Antonin Dvorak (1841–1904)

Zdenko Fibich (1850–1900)

Leos Janacek (1855–1928)

Hans Trnecek (1858–1914)

Josef Bohuslav Foerster (1859)

Emil Nikolaus Reznicek (1861)

Karl Kovarovic (1862–1920)

Karel Weis (1862)

Stanislaus Suda (1865)

Karl Navratil (1867)

Vitezslav Novak (1870)

Adolf Piskacek (1874)

Camillo Hildebrand (1876)

Otakar Ostrcil (1879)

Otakar Zich (1879)

Rudolf Karel (1881)

Bohuslav Martinu (1890)

Karl Goldmark (1830–1915)

Alphons Czibulka (1842–1894)

Jeno Hubay (1858)

Julius J. Major (1859)

Emanuel Moor (1862)

Georg Jarno (1868–1920)

Béla Bártok (1881)

Emil Abrányi (1882)

S�����������

Johan P. E. Hartmann (Danish) (1805–1900)

Ivar Hallstrom (Swedish) (1826–1901)

Eduard Lassen (Danish) (1830–1904)

Emil Hartmann (Danish) (1836–1898)

Anders Hallen (1846)

Peter Lange-Müller (Danish) (1850–1926)

Christian Sinding (Norwegian) (1856)

Gerhard Schjelderup (Norwegian) (1859)

H��������

August Enna (Danish) (1860)

Wilhelm Stenhammar (Swedish) (1871)

Hakon Boerresen (Danish) (1876)

Paul August von Klenau (Danish) (1883)

Ture Rangstrom (Swedish) (1884)

Jan Sibelius (1865)

Selim Palmgren (1878)

Armas E. Launis (1884)

Michail I. Glinka (1804–1857)

Alexander S. Dargomyzsky (1813–1869)

Alexander Serov (1820–1871)

Anton Rubinstein (1830–1894)

Alexander P. Borodin (1834–1887)

César Cui (1835–1918)

Modest Moussorgsky (1839–1881)

Peter I. Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908)

Michail Ippolitov-Ivanov (1859)

Anton Arensky (1861–1906)

Alexander Gretchaninov (1864)

Alexander Glazounov (1865)

Vladimir Rebikov (1866)

Arseni Korestchenko (1870)

Serge Rachmaninov (1873)

Igor Stravinsky (1882)

Serge Prokofiev (1891)

Ladislas Zelenski (1837–1921)

Sigismund Noskowski (1846–1909)

F������

R������

P�����

Ignace Jan Paderewski (1860)

Karol Szymanowski (1883)

Ludomir von Rozycki (1883)

Raoul Koczalski (1885)

R��������

Theodor Flondor (? 1908)

E������

Thomas Campion (1575–1620)

John Coperario (1580)

William Lawes (1582–1645)

Henry Lawes (1596–1662)

John Banister (1630–1679)

Matthew Lock (1632?–1677)

Henry Purcell (1658–1695)

Thomas Arne (1710–1778)

William Shield (1748–1829)

Stephen Storace (1763–1796)

Henry R. Bishop (1786–1855)

John Barnett (1802–1890)

Julius Benedict (1804–1885)

Michael William Balfe (1808–1888)

George A. MacFarren (1813–1887)

William Vincent Wallace (1814–1865)

Frederic Clay (French) (1838–1889)

Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900)

Alfred Cellier (1844–1891)

Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847)

A. Goring Thomas (1851–1892)

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924)

Frederick Corder (1852)

Frederic Hymen Cowen (Jamaica) (1852)

Ethel Mary Smyth (1858)

Isidore De Lara (1858)

Marie Wurm (1860) (Living in Germany)

Liza Lehmann (1862–1918)

Edward German (1862)

Frederick Delius (1863)

Eugene d’Albert (1863) (Living in Germany)

Edward Woodall Naylor (1867)

Gustav Holst (1874)

Josef Holbrooke (1878)

Albert Coates (Russian) (1882)

Hubert Bath (1883)

Lord Berners (1883)

William H. Fry (1813–1864)

George Bristow (1825–1898)

A�������

John Knowles Paine (1839–1906)

Frederic Grant Gleason (1848–1903)

William J. McCoy (1848)

Max Vogrich (Transylvanian) (1852–1916)

George W. Chadwick (1854)

Julian Edwards (English) (1855–1910)

Humphrey John Stewart (English) (1856)

Richard Henry Warren (1859)

Reginald De Koven (1859–1920)

Victor Herbert (Irish) (1859–1924)

Pietro Floridia (Italian) (1860)

Walter Damrosch (1862)

Horatio W. Parker (1863–1919)

Ernest Carter (1866)

N. Clifford Page (1866)

Paolo Gallico (Austrian) (1868)

Wallace A. Sabin (English) (1869)

Louis Adolphe Coerne (1870–1922)

Joseph C. Breil (1870–1926)

Henry K. Hadley (1871)

Frederick Converse (1871)

Arthur Nevin (1871)

Mary Carr Moore (1873)

Theodore Stearns (?)

Frank Patterson (?)

John Adam Hugo (1873)

Albert Mildenberg (1878–1918)

Ernest Bloch (Swiss) (1880)

Charles Wakefield Cadman (1881)

Simon Buchhalter (Russian) (1881)

Lazare Saminsky (Russian) (1883)

Louis Gruenberg (1884)

W. Frank Harling (?)

Isaac Van Grove (?)

Timothy Spelman (1891)

Eugene Bonner (?)

Modern Ballets

R������

Peter I. Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908)

Alexander Glazounov (1865)

Arseni Korestchenko (1870)

Nikolai Tcherepnin (1873)

Igor Stravinsky (1882)

Maximilian Steinberg (1883)

Serge Prokofiev (1891)

P�����

Karol Szymanowsky (1883)

Alexandre Tansman (20th Century)

F�����

Léo Délibes (1836–1891)

Emanuel Chabrier (1841–1894)

Jules Massenet (1842–1912)

Vincent d’Indy (1851)

André Messager (1853)

Alfred Bruneau (1857)

Gabriel Pierné (1863)

Erik Satie (1866–1925)

Charles Silver (1868)

Florent Schmitt (1870)

Jean Roger Ducasse (1875)

Maurice Ravel (1875)

Louis Aubert (1877)

Louis Durey (1888)

Roland Manuel (1891)

Darius Milhaud (1892)

Arthur Honegger (1892)

Germaine Taillefer (1892)

George Auric (1898)

François Poulenc (1898)

Henri Sauguet (20th Century)

I������

Franco Alfano (1877)

Ottorino Respighi (1879)

Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880)

G. Francesco Malipiero (1882)

Alfredo Casella (1883)

Vittoria Rieti (1898)

S������

Manuel de Falla (1876)

H��������

Béla Bártok (1881)

S�����������

Kurt Atterberg (Swedish) (1887)

A�������

Arnold Schoenberg (1874)

Egon Wellesz (1885)

C�����-S��������

Karl Kovarovic (1862–1920)

Georg Kosa (1897)

Bohuslav Martinu (1890)

E������

Arthur Seymour Sullivan (1842–1900)

Ralph Vaughn Williams (1872)

Gustav Holst (1874)

A�������

Henry F. Gilbert (1876–1928)

John Alden Carpenter (1876)

Charles Griffes (1884–1920)

Emerson Whithorne (1884)

Deems Taylor (1885)

Cole Porter

Leo Sowerby (1895)

INDEX A

Absolute music, 239–40, 242, 397, 422

Abt, Franz, 423–4

Adam de la Halle, 102, 112, 125

Aida, Verdi’s, 379–81

Albéniz, Isaac, 453–4

Alcuin, 76

Alfred the Great, 93

Alphonso XII of Spain, 453

Ambrose, St., 71, 72

America, see United States

American Academy in Rome, 507–8

American composers, 475 ff.

American folk music, 140–5

American Music Guild, the, 506–7

American opera companies, 514

American patrons of music, 512–13

American song writers, recent, 509–10

American symphony orchestras, 513–14

Anglican church, founding of, 188

Anglin, Margaret, 469

Antiphony, use of, by the Greeks, 41; introduction into church music, 70

Apollo, 33–4

Arabia, music of, 55 ff., 209, 210; the Arab scales, 58–9; instruments of, 59–61

Arcadelt, Jacob, 157

Armide, Dvorak’s, 447

Arne, Dr. Thomas, 200, 339

Assyrian music, 24–5

Atonality, 517, 529

Auber, Daniel François Esprit, 333–4

Aulos of the Greeks, 42–3

Austrian National Hymn, written by Haydn, 282

Automatic pianos, 316–19

Aztecs, music of the, 53–4

Bach, Johann Christian, 254

Bach, Johann Christoph, 254

BBach, Johann Sebastian, 208, 211, 238, 240; account of his life, 244–50; his works, 250–3; his sons, 253–4; comparison with Handel, 255–6

Bach, Karl Philip Emanuel, 249, 253–4

Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann, 253

Bach Festival, yearly, at Bethlehem, Pa., 252, 464

Bagpipes, the Roman tibia, 45; use of, by the Hindus, 66; of the Bohemians, 135;

of Scotland, 138

Baif, Jean Antoine, his club of poets and musicians in France, 177

Balakirev, Mily, 444–5

Balfe, Michael William, 341

Ballad, the, and the ballet, 122

Ballet, the, at the French court in second half of the 16th century, 178

Band, the difference between, and an orchestra, 234

Bantock, Granville, 543

Barber of Seville, Rossini’s, 337

Bards of ancient Britain, 89–91

Barnby, Joseph, 340

Bartlett, Homer W., 490

Bartok, Béla, 536–7

Bauer, Marion, 507

Bax, Arnold, 544

Bay Psalm Book, the, 458

Bayreuth, 371–2, 373

Beach, Mrs. H. H. A., 480–1

Beaumont and Fletcher, 173

Bede, the venerable, 75–6, 92

Beethoven, Ludwig van, 293 ff.; account of his life, 295–302; his friendships, 298–9; The Moonlight Sonata, 300, 304; his three periods, and works during, 301–2; his opera Fidelio, 302, 305, 306, 326; influence upon the growth of music, 303–5; as a composer of instrumental music, 305–6; his preference in pianos, 313; the Kreutzer Sonata, 324;