6 minute read

THE FOREST CLASSROOM

Above: Looking up into the canopy of an ash-dominated northern hardwood forest. Inset: The author holds a cluster of ash seeds.

Advertisement

Foresters Take an Active Approach to Protecting Ash

By Gabe Roxby

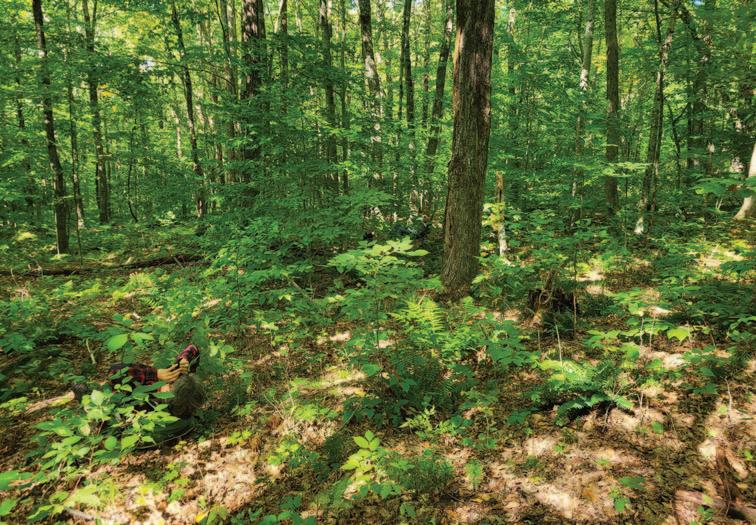

In mid-September, Forest Society Forester Steve Junkin, Senior Technology Specialist Allan Krygeris, Cheshire County Forester Matt Kelly, volunteer Sarah Thorne, and I armed ourselves with binoculars and flagging tape to search for and tag female ash trees. Walking in a line, we scanned the lower flanks of Monadnock Reservation, one of the Forest Society’s most spectacular stands of white ash. This stand has yet to be impacted by the emerald ash borer, an invasive insect which will likely arrive here in the next few years. The search was slow going; our necks were starting to hurt, and I hadn’t found a single female ash tree yet! Morale was dipping.

To understand what prompted this initially fruitless search for female ash trees, we need to understand more about the plight of ash in our forests. The emerald ash borer (EAB) is an invasive forest pest that has been decimating native ash tree populations across North America since it was first detected in Michigan in 2002. The first sighting in New Hampshire was in 2013, and since then, this invasive insect has spread rapidly to nine of the state’s ten counties. At the moment, there is little chance of preventing the near-complete loss of all of the mature ash trees in our forests.

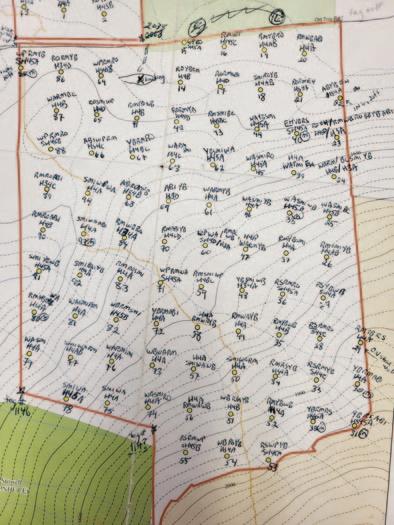

Left: A map from the most recent forest inventory allowed the group to pinpoint the parts of the forest that had the heaviest concentration of ash. Right: Look closely! Can you spot three people in this photo searching for female ash trees?

Currently, the best hope to retain ash on our landscape is through the introduction and establishment of biocontrol insects. The hope is that the introduced insects, which parasitize EAB eggs and larvae, will control borer populations so that they can co-exist with ash, similar to the way many of our native borer beetles behave. However, EAB has a head start, and the biocontrol insects do not have much of a chance of stopping the initial killing wave of EAB before most of our large ash trees are wiped out.

This all sounds bleak, but there is a glimmer of hope. EAB does not seem to kill seedling and sapling ash trees, which provides an opportunity for foresters to manage ash stands in a way that may help retain ash on our landscape. The thinking is that if we can establish young ash trees in the understory of our forests, they will be able to survive the initial wave of EAB.

White Ash Lament

By Sarah Thorne

Solemly We bushwack into the waiting forest. Forming a line five abreast, A search party for White Ash. We are in pursuit Of healthy females in the canopy. Arrow-like seeds on the ground Call us to attention.

Spinning beneath towering trunks, We look for portals to their crowns. Up, up above the lesser trees, Ash proclaim dominion. Why do males outnumber females 7:1? We contemplate the secrets of ash, Gazing through our binoculars, Peering into realms of dioecious exchange. We lie on the ground To save our necks, Steady our hands, And commune with the majesty. The trees are oblivious, Flinging their boughs to the sky Festooned with tinges of autumn. Is this one a female? There, caught in the sunlight, Glittering like crystals, Seeds have already begun flying. Your roots, your trunk, your branches Grew as bulwarks for a century of seeds, Alighting in their coveted spots In the community of Monadnock. But global trade and human hubris Intervened Invaded Eliminated.

Now, what can we offer? Inoculation for a small refugia Of the Monadnock gene pool, Precious seeds full of hope? A regeneration harvest To jumpstart a new generation? A parasite for the borer That won’t out-bore us?

Will this be your last season of glory? Will this be the last autumn you Scatter your gems across the forest? I lay transfixed by dancing branches Wanting to remain forever In dappled sunshine Beneath the living matriarchs. Beseeching them to survive.

As these young ash trees grow, it is possible the biocontrol insects that are being released now will have time to become better established and may afford some protection as the ash trees grow larger. Additionally, if there is some genetic resistance to EAB in some ash trees, stands with thousands of small ash are more likely to contain a tree sapling with this resistance than a stand with only a dozen large ash trees. More ash trees per acre gives us a greater chance that one of those trees might contain something important in its genetics that could help us retain ash in our forests.

In the next few years, the Forest Society is planning to implement a timber harvest on one of our best ash stands on Mount Monadnock with the goal of regenerating a blanket of white ash seedlings. Since a single ash tree is either a male or a female (in some tree species this isn’t the case and a tree may have both male and female parts), it will be important to make sure we leave some of each uncut during the harvest to provide the species an opportunity to pollinate and set viable seed.

Females aren’t as common as males, and some estimates put the ratio at only one female tree for every seven male trees. During the harvest, foresters want to make sure they leave enough female trees so they can provide an opportunity for ash to regenerate.

But how do you tell if an ash tree is male or female? It can be difficult to tell because female ash trees only produce large amounts of seeds every three to five years on average. Fall 2022 has been an excellent seed year for white ash across the region, hence our ash seed recon at Monadnock Reservation.

Our initial strategy was to walk in a line looking at the crowns of each ash tree for seeds. This method was brutally slow as it was difficult to see the seeds in the crowns of these impressively tall trees, especially with the leaves of nearby trees obscuring our view.

After about an hour, we settled on a much better strategy: around each ash tree we found, we surveyed the base of the tree for seeds. If seeds were spotted, we lay down on our backs and searched that tree for seeds in the canopy. It turns out, at this time of the year at least, many of the ash seeds didn’t fall far from the tree, and so this method allowed us to refine our search. We lucked out on this field day, as we found ash seeds both on the ground and in some trees. Searching for female ash trees in late fall can also be fruitful, as the trees hold onto their seeds and seed stalks long after all the hardwood trees have dropped their leaves. Scanning tree crowns can be much more efficient during these months than when trees still have leaves.

Now knowing where the female ash trees are in this stand, we can make better choices on which trees to leave uncut during the harvest. We still have more to figure out on the timing of the harvest, and the pattern and density of the trees we will leave uncut, but this felt like a good first step.

Cheshire County Extension Forester Matt Kelly flags a female ash tree on the flanks of Mount Monadnock.

Gabe Roxby is a forester for the Forest Society.

Learn More

Learn more about the emerald ash borer and report sitings of the species to UNH Extension at nhbugs.org.

If you’re interested in conducting similar management aimed at retaining ash on your land, please contact Gabe Roxby at groxby@forestsociety.org.