5 minute read

Look at a 1970 Union Murder

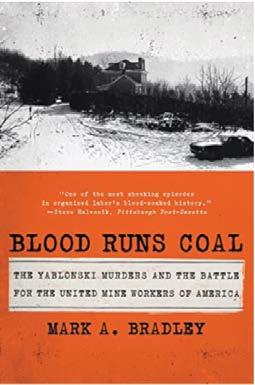

BLOOD RUNS COAL:

A Modern Look at a 1970 Union Murder

By Mark Ashton, Esq. Fox Rothschild, LLD.

Mark A. Bradley; W.W. Norton Fall, 2020

We live in contentious times. Many would say these are unprecedented times where there are entirely divergent views of America’s future direction.

History says otherwise. Our country experienced widespread violence in the 1840s over whether Catholic immigration would ruin America. We saw a million killed or wounded over whether eleven states could secede and retain slavery as an institution. In 1968 the murder of Martin Luther King triggered major riots in six American cities while, anger over the draft and our involvement in Vietnam prompted hundreds of protests culminating in riots in Chicago during the Democratic nominating convention. Almost 1,000 were injured.

While decidedly more violent, the battles of 1968 are not much different than those of today. Half of us embrace the way things were when America was “great.” The other half suggest that things are far from “great” and change is required.

Attorney Mark Bradley’s history of the murders of Joseph Yablonsky and his family on December 31, 1969 reminds us how badly people react when they perceive themselves as threatened. The United Mine Workers were organized in 1890. Like other elements of organized labor, they experienced a rocky start until 1920 when John Lewis took over and made the miners a central element of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Lewis took the miners out of the CIO in 1942 and headed the union until 1960. He was revered by the humble men for whom he fought and when he told them that Tony Boyle was a worthy successor, they never questioned that endorsement.

Although he came from a mining family, Boyle was an odd choice. He never was really in touch with the rank and file and some miners thought he ignored their economic and safety needs. But others accepted Boyle’s heavy-handed control of the union. After all, he was John Lewis’ guy.

Unions in the 1960s were more autocratic than democratic. Leaders like Boyle could hand pick their boards and decide whether a member did or did not get

his pension. In the case of the United Mine Workers, millions of dollars were on deposit at the unioncontrolled National Bank of Washington. Those deposits paid no interest to the union. Pensioners were paid $1-$2 a days after years in the mines. It didn’t make a big difference because black lung and related diseases meant the pensions were paid for just a few years before the miner died.

In November 1968 the fans that carried explosive methane gas out of the Consolidated Coal Mine in Farmington, West Virginia stopped working. This was not a surprise, as the mine’s own records showed it had spent $1 a month on mine safety training in 1968. 78 miners suffocated to death 600 feet below ground. The mine operators sent a plane to Washington to bring union head Tony Boyle to the mine. With hundreds of union family members waiting to hear their leader, Boyle told them that Consolidated had a good safety record and that these things happen to people who work in the mines.

Joseph “Jock” Yablonsky was a long-time union operative who questioned Boyle’s leadership yet kept his views to himself. But watching Boyle excuse the employer for 78 avoidable deaths was too much. He had abided rampant corruption and watched previous challenges to Boyle’s authority brutally punished. This time, however, Boyle and his coterie had treated avoidable death as inevitable.

When Yablonsky announced he would run against Boyle to head the union, nearly everyone in the union hierarchy was incredulous. Yablonsky knew his chances were slim and his life was in jeopardy. Boyle had support of union locals with a history of addressing union problems with a miner’s weapon of choice; dynamite.

What Yablonsky would not have expected was that Boyle would knowingly contract for him to be murdered. Perhaps even more bizarre was the fact that the murder was effected weeks after Boyle had decisively won reelection with a 64% majority.

The story of the union, the election challenge to Boyle, the murder and the trials is told crisply by the author in 240 pages. The murder, which included the gunshot death of Yablonsky, his wife and daughter in their Clarksville, Pennsylvania farmhouse on New Year’s Eve 1970 is a decidedly blue-collar affair. The theme is common. Well-off people in power identify and pay people on the margins of life to execute the Yablonsky family as they sleep in their beds. The union leaders involved act because they view a threat to Tony Boyle as a threat to them, to the union way of life and to democracy itself. Sound familiar?

The identification of the actual killers is almost too simple. They stalked Yablonsky for months in ways that were both rudimentary and ineffective. They searched for their prey in a town of 300 people and made no effort to hide their presence from Yablonsky’s neighbors. Confronted with hard evidence of their involvement, the killers turned on each other.

The murders came to light five days after they occurred when Yablonsky’s son in Washington could not reach his parents and sister. Recognizing that there was likely a conspiracy, local and state officials turned to the FBI to assist the State Police and to Philadelphia’s star assistant district attorney Richard Sprague, to secure convictions. Sprague was lucky in the sense that the murders were easily traced, and the defendant was easy to flip. But the second step was tracing the money, first to a union local in Tennessee that was happy to provide their union leader with revenge for Yablonsky’s challenge and then to union headquarters in Washington and Boyle himself. Along the way Sprague tried the killers in Greene County, southwest of Pittsburgh, the union local conspirators in Erie and finally Tony Boyle. Boyle’s murder conviction was reversed by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and a second trial ordered to be held in Media, Pennsylvania in 1978. That trial brought together three legends. Sprague, defense attorney A. Charles Peruto and President Judge Francis Catania. Boyle was convicted a second time in a trial where Peruto promised evidence he later acknowledged to the jury he could not produce.

The story is a page turner, deftly told by an experienced attorney. As a person who came of age in the late 1960s and watched American cities burn between 1967 and 1970, Blood Runs Coal reminds this writer that today’s political polarization has real parallels with the turbulence of the 1960s. Boyle and his cohorts professed that only they could save the union from the coal companies, other unions and “communists” like Jock Yablonsky. In the end, Yablonsky and his family were martyred for the sake of these demonstrably false narratives. Then is not now, but as Antonio said in the Tempest, “What’s past is prologue; what to come is yours and my discharge.” In a word, there is merit in study of the past, but the future is in our hands.