Introduction INTRODUCTION

The project began in 2017. Researchers Dr Roxanne Ellen Bibizadeh and Professor Rob Procter conducted focus groups with over one hundred young people in England between the ages of eleven and twenty-one and interviews with teachers.

The findings highlighted that there is an abundance of online safety educational resources available but there are discrepancies in the delivery and messages conveyed to young people.

Our research revealed that children and young people have a paradoxical relationship with the Internet because they feel both free and unfree online. They reported the Internet offered “refuge” and a form of “escape”, and at the same time they were also concerned about how their data was being used and described feeling the need to self-censor and conceal their online activities.

Overwhelmingly young people felt they were spoken to and not heard, and they found it difficult to have

conversations with adults about their online lives who they believed lacked understanding (Bibizadeh et al.).

The next phase of the research project began in December 2019 and sought to address why these conversations between educational professionals/parents/carers and children and young people are intimidating and how this might be remedied.

The project aimed to achieve this by interviewing experts working within the field of online safety including academics, government officials, NGO’s, and social enterprises. We hoped to draw on their experiences to identify what provisions currently exist to support children and young people online and what are the potential collaborative solutions to existing risks and challenges online.

Children are growing up online and experiencing an array of digital dangers such as commercial exploitation, cyberbullying, exposure to pornographic content, hate or self-harm materials and the image sharing and live streaming of child sexual abuse (UNICEF 2017, 72-3).

Three months into the research project the UK was experiencing the first lockdown due to the global pandemic. The United Nations reported that the pandemic had created the largest disruption to education systems in history with nearly 1.6 billion learners in more than 190 countries and all continents affected, impacting 94% of the world’s student population (UN 2020, 2). One of the many impacts of school closures is that children and young people are spending large amounts of time online.

4

DEYP Summary Report

Within the first month of lockdown the specialist cybersecurity company Web-IQ revealed there was an increase of over 200% in posts on known child sex abuse forums that link to downloadable images and videos (Donovan and Redfern, 2020). Additionally the Internet Watch Foundation recorded an 89% reduction in child abuse materials being removed from the Internet in the first four weeks of lockdown, as investigators struggled with their workload during the pandemic (Donovan and Redfern 2020). eSafeGlobal reported during lockdown there has been three times more sexting and grooming incidents than normal, including grooming minors as young as ten, and twenty-five times more incidents of children and young people talking to strangers (NPCC 2021, 4). The National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children registered a 106% increase in reports of suspected child sexual exploitation – rising from 983,734 reports in March 2019 to 2,027,520 in the very same month in 2020 (Brewster 2020).

The COVID-19 crisis has moved our lives online, and this has increased children and young people’s vulnerabilities to online harms.

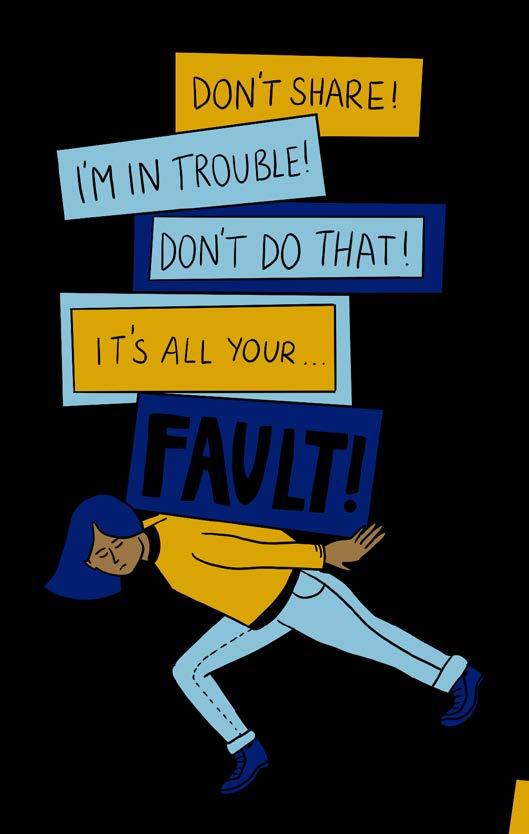

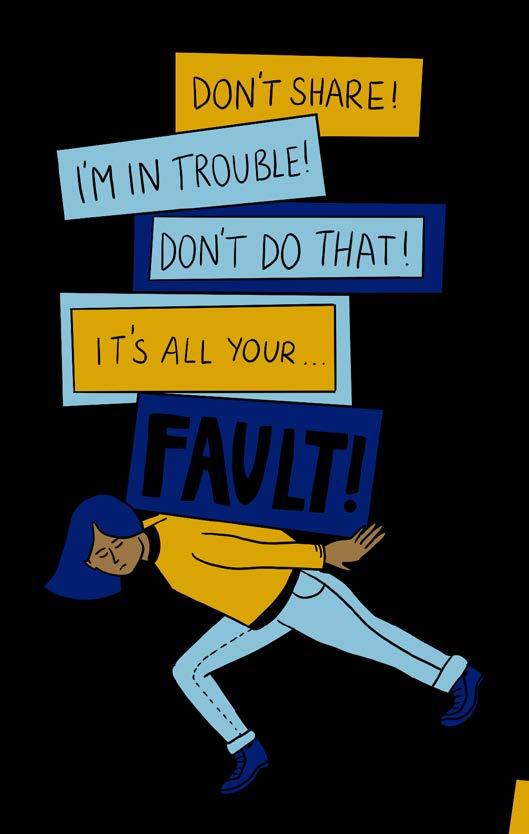

Our findings suggest that historically online safety educational resources tend to place the onus on young people preventing an online harm through a form of responsibilisation to, for example: “not post” or “think before you post”. The impact of such messaging is that it creates a culture of victim blaming. The responsibility is placed on the young person who sent the original message rather than the person who has shared it without consent. Such messaging creates an unhealthy culture that reduces the opportunity for communication and support.

Our research indicates if we address the pertinent issue of a lack of open communication between adults, children and young people, we may be able to prevent both lower and higher level online harms, because children and young people will feel more comfortable talking to adults about their online lives.

This report will be useful for educators, policy makers, law enforcement agencies and parents and carers who are working to support and enable children and young people’s digital well-being. Our hope is that this research will be used to inform the development of new educational approaches, assist in a review of law enforcement agencies handling of victims of abuse, encourage a rethinking of the language used in online safety education, and updates to existing materials.

It should be acknowledged that the findings within this report are not conclusive, but we hope that these discussions will provide a crucial insight from the leading experts in the field.

We invite others to draw on the findings from Digitally Empowering Young People to develop interventions and strategies in this space.

5

DEYP Summary Report

KEY FINDINGS DEYP Summary Report

Four themes were identified during the data analysis:

The Internet has become a “vital part of children’s ability to communicate and express themselves” (Internet Watch Foundation). Some of the experts we spoke to felt there was an unhelpful focus on the risks and challenges the Internet poses to young people when in actuality we should be celebrating the benefits it creates. Alan Mackenzie (AACOSS) pointed out that schools were particularly prone to focusing on the risks rather than engaging with the opportunities.

Some of the experts we spoke to revealed that in their experience they had found that the Internet was particularly beneficial for vulnerable children and young people. For example, Adrienne Katz (Youthworks) drew attention to responses collected from vulnerable young people during one of her focus groups: one boy wrote, “It’s a window on the world.” And one said in our workshop, “I used social media to join society.” Similarly, Rebecca Avery (The Education People) discussed how “for some of our most vulnerable young people those online friendships, as long as they are healthy relationships can actually be really vital for giving them support that perhaps they don’t have elsewhere.” Additionally, a member of the Family Support team highlighted that some of the young people they work with use the Internet and social media acknowledged within the community and essentially maybe the world... some of the young people I work with use social media as a way of being entrepreneurs. I worked with one young girl... she was very into fashion and designed T-shirts. She used Instagram as a platform to sell her clothes, and for her it was a really positive thing.”

as a means to support their creative endeavours: “They see it as a platform to get themselves noticed and

The Internet and social media offered vulnerable young people a way of accessing support and building relationships that are unavailable to them in real life. It also offered a way for children and young people to pursue their ambitions and explore their creativity. A member of the Family Support team described it as a “powerful tool” for young people.

7

1. The Internet: “A Powerful Tool”?

1. The Internet: “A powerful tool”?

2. Constructive Communication

3. Enhancing Vulnerabilities by Responsibilising and Victim Blaming

4. Online Safety: Outdated Education?

The risks and challenges are evolving and this has transformed the sector and the advice and guidance parents and schools are seeking. Rebecca Avery (The Education People) explains that “the focus has very much been on the risk from strangers […] the most common issues I deal with is more around peer on peer abuse and around the content that children access […] we’ve got issues around pornography but we also are now starting to look at the issues around self-harm related material, pro-eating disorder related material, pro-suicide material, which are new issues that I’ve been dealing with”.

The Internet Watch Foundation identified that the major online risks centre around young people not understanding the difference between their online and offline lives, and as such this results in “over-confidence and over-sharing”, not “understanding necessarily the permanence of some of the interactions that are taking place online”, and that they can be deceived.

The pressure the Internet creates on young people to “construct themselves and present themselves in a certain way” was also noted by Kate Burls (CEOP National Crime Agency) to be an issue young people are struggling with online. It is often assumed by parents/carers and educational professionals that there is a need to understand what young people are doing online, and that they therefore need to be aware of all the latest trends, popular games and apps.

However, Mark Bentley (LGfL) contends that the best way to help children and young people online is to realise that most risks and challenges are not innate to the online world, which he argues often “holds a mirror to society rather than generating entirely new behaviour”.

Vicki Shotbolt (Parent Zone) encourages us to think positively about the opportunities the Internet offers us, rather than focusing on the dangers. “[T]echnology’s coming into family life so fast and society hasn’t adapted around it, we have a real difficulty with encouraging young people to maximise the opportunities of technology. So for me the single biggest risk is that we miss the opportunity to make technology something that young people really benefit from.” Our research revealed that it is difficult to balance the opportunities and benefits the Internet affords children and young people, whilst also attempting to prevent online harms and support the development of digital wellbeing.

2. Constructive Communication

The support children and young people want contrasts what parents/carers and educational professionals think they need. Claire Levens (Internet Matters) explains that through their research and engagement with children and young people they have learnt that:

8

DEYP Summary Report

“what the young people are saying to us is: “We want you to be kind and compassionate and give us the time that we need to learn to trust you.” And what we’re hearing from the professionals is, “Training, you’ve got to train me. I don’t understand TikTok so I need a course on TikTok. Professionals are trying to chase down their understanding of the tech, which is kind of logical but misplaced, because the young people are saying, “we need you to treat us like people.””

Claire Levens, (Internet Matters)

In order to address this, Internet Matters are seeking to understand what the characteristics of trust in adults would look like for children and young people, as they believe this is crucial to enabling more open conversations. Similarly, Adrienne Katz (Youthworks) makes the point that it is impossible to keep up with the trends, “[s]o that’s why the only pathway for parents and teachers is dialogue”.

Alan Earl (AACOSS) described how he attempts to engage with children and young people to encourage honest and open conversations. One way he attempts to achieve this is by expressing interest through asking

lots of questions:

“If you get ten minutes at the end of a lesson actually ask your kids what they’re doing online, what’s really hot, what’s fun, what’s bad, because you will learn so much, because kids want to speak to adults about this. Every conversation I’ve ever had with a kid, they generally tend to agree they would want to speak to adults about this, they don’t feel capable of doing so for different reasons often, but they don’t feel capable, or confident in having a conversation with adults because they don’t see adults as taking much of an interest in what they do online. […] So, the messages the kids tend to get from adults generally, and in school, is, “There’s danger there, don’t spend too much time online. Don’t talk to strangers.” All the sort of old messages that were still there ten, fifteen years ago, still are repeated. Not a case of, “Okay. What’s going on online? How do you use this tool? What do you think are the benefits? Wow, that’s brilliant. What about if that was happening? How would you deal with that? What about this, how does that make you feel?” These are honest conversations. So I still think there are not enough honest conversations. I would say that’s across schools but also across adults in general in relation to young people.”

Rather than asking questions, there is a tendency within schools and at home to resort to limiting or banning access to the Internet and technology in an effort to protect children and young people from harm, but as Lorin LaFave explains in prohibiting her son Breck from using the Internet “it became that much more dangerous because it all went underground. I didn’t realise that enforcing a rule would actually make it worse by making it become secretive”(Breck Foundation). Peter Watt (Family Support) argues that in his experience of working with families there is a tendency to rely on parental controls within the home and this he argues creates a false sense of security. “[M]y worry

9

DEYP Summary Report

about parental controls is that they make parents feel they’ve done their job, when actually what they need to be doing is having conversations with their kids about what is safe, not safe, appropriate and inappropriate. […] And obviously the older kids get they just work round it, so it’s a false sense of security. And it sends the wrong message I think you should also be trying to teach kids responsibility. So I think they’re a tool, but they’ve got to be seen as a tool that’s in aid to the conversations you should be having.”

Vicki Shotbolt makes the case that “parenting is the thing that has the biggest influence on children’s outcomes, and poverty. That hasn’t changed regardless of the digital world.” (Parent Zone)

Similarly, Kate Burls states that healthy relationships between parents/carers and children are crucial to online safety: “it doesn’t really matter whether it’s online or off, it’s all about healthy relationships and behaviours […] the best, sort of, parenting for keeping children safe online is around parents having really positive relationships with children, having open conversation, being involved in a positive way in their child’s Internet use so not surveillance but knowing what their child’s up to because they’re having these positive conversations with them about it. And then they can, sort of, drop in some advice and their child will listen and their child will go to them if they are in trouble […] children are much safer if they have positive and engaged and non-prohibiting sort of relationships with their parents.” (CEOP NCA)

It is widely accepted that a child or young person’s home life affects how safe they are online. Lorin LaFave (Breck Foundation) explains that if parents or carers are relied upon to provide the main source of online safety education and protection then there will be a lack of consistency because not every parent has the same amount of knowledge, understanding and availability, and there will be differences in the relationships between parents/carers and children. Furthermore, Adrienne Katz emphasises the importance of recognising the vast differences and complexity of familial circumstances that can impact a parent/ carer’s ability to provide online safety education. “It’s not really practical to suggest that all parents across the country have the capacity to deliver this. Where they are able to, they need the support and they need the resources. But there are some who will struggle. And we have to be honest about that. […] So, I think it’s not a command culture. We cannot just command parents to do things and we can’t command kids not to do things. […] So parents shouldn’t be disenfranchised.” (Youthworks) The key to a child or young person’s online safety is to find ways to support and empower parents and carers.

Katz suggests intergenerational learning may be the key to engaging parents and carers and helping them to understand how to better support children and young people. She advocates for schools to enlist young people to volunteer to educate parents about their online lives. “[O]ften getting a few volunteers, students who are a few years older than the class you’re addressing works well. And then the parents seem less ashamed to talk to them and ask them what seem to be stupid questions, than they would to the teachers. So they sit at a computer and the young person can show them what goes on in gaming and in social media and in other things. And the parent can ask questions and somehow it works much better as a sort of intergenerational thing. And they have to be at least say four years older than your child.” (Youthworks) All our experts emphasised that developing and maintaining positive relationships with children and young people is integral to keeping them safe online.

10

DEYP Summary Report

Annie Mullins OBE, like many professionals we interviewed, was concerned by the trend of responsibilising young people.

“I don’t think we can expect young people and children to protect themselves from very advanced criminals who are devoted to seducing them and to entrapping them. I think that’s too big a responsibility.”

Annie Mullins (OBE)

The tendency to responsibilise young people into the protectionist role can result in vulnerabilities being exploited online. As Alan Earl explains, “technology can enhance that vulnerability with young people in a setting where they are already vulnerable” (AACOSS).

In our first finding we pointed out that the Internet can be particularly beneficial for vulnerable children and young people, our discussions also highlighted that this vulnerability can also make them more likely to fall victim to abuse online because they were more likely to be lacking support structures offline. An anonymous contributor (AC) to the project explained that vulnerable young people’s overreliance on the Internet for support resulted in increased vulnerability.

The AC argues that the mistake often made is to offer extra education about online safety for those that are vulnerable, when in actuality more offline support structures are needed to reduce the reliance on online spaces.

(anonymous contributor)

The Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) highlighted that there is a need for further research to understand “selfgenerated content”. IWF outlines that:

“self-generated content is typically being produced by “11 to 13 year old girls in home settings […] children who are on social media, who are seeming to be tricked and coerced for ‘likes’, it seems to be more of a sort of popularity based thing where younger children perhaps aren’t even aware necessarily of the nature of the acts they’re being asked to perform. But they’re being told if they do a particular thing they can get up to 500 ‘likes’ And that’s clearly something that really resonates with some of these younger 11 year olds. When we’re looking at the higher age ranges, up around the 13s/early teens it does seem to be more in the nature that some of these girls think they’re actually in a relationship with some of these people. […] Typically the sort of scenario we see is a sort of bedroom or home setting, bathroom typically, seemingly relatively affluent, we can hear adults sometimes within the house, completely unaware that this is occurring. So I think really trying to pin down what this particular vulnerabilities might be I think is really important area of research.”

11 3. Enhancing

Vulnerabilities by Responsibilising and Victim Blaming

DEYP Summary Report

In order to prevent children and young people’s vulnerabilities from being exploited and manipulated online there needs to be more offline support structures, and a greater understanding of the connection between particular vulnerabilities and certain online harms. Kate Burls for CEOP, the National Crime Agency explains that organisations producing online safety resources need to strike a balance “between empowering but not responsibilising”. She argues there is a link between the historic culture of victim blaming in online safety educational resources and how this responsibilises the child. She explains:

“often organisations like ours and others were falling back on messaging like “Think before you do X. Well you’re going into a classroom, you’re saying that to loads of children that have done x already. And by implication that’s victim blaming […] [a] sort of responsibilisation of the child because children are children and it’s adults who have the responsibility to safeguard them”. (Kate Burls, CEOP, NCA)

The AC asserts online safety education that responsibilises young people makes them more unsafe online:

“the curriculum they’d had has told them that they shouldn’t share an image of themselves. So if they do share an image of themselves with somebody and then that person onward shares it, they are to blame for sending it in the first place, because they all experience the same education. So some of the messaging to schools has been to focus more on not onward sharing rather than focusing on the don’t share in the first place. Because if you don’t, if you focus on the don’t share in the first place message, you create an environment that’s very rich in blaming for any child that does share an image of themselves and then that image is onward shared. And this reduces the capacity of that young person to seek help because they would say to us, “I’d get in trouble, ‘cause I should never have sent it to my partner in the first place, so I’d get in trouble if I told someone what had happened.” So, […] their ability to, kind of, support each other online to disrupt harmful messaging or to reinforce it online is informed by the school environment.”

Rhiannon-Faye McDonald for the Marie Collins Foundation also highlights the importance of reframing the language used when speaking to children and young people to ensure the perpetrators are held accountable rather than the victims: “if they’re told, “Don’t do this, don’t do that,” and they do it then […] that could feed into them feeling blamed for what happened. So, I think the message really has to move towards, don’t be embarrassed or ashamed if something has happened or if you have done something but do feel able to come and speak to us about it.”

12

DEYP Summary Report

McDonald campaigns for more thoughtful communication with victims of online abuse, particularly from law enforcement agencies. She advocates for a rethinking of how law enforcement agencies contact victims of abuse, whether the contact is direct or through a parent or carer, more consideration of how the gathering of evidence could cause further harm and distress, and how a victim might gain closure from some form of involvement in the prosecution of the perpetuator of the abuse.

Ultimately, she observed that there is a need to ensure that the language used when speaking to a victim does not further victimise them, and that most importantly the victim knows it is not their fault.

This historic culture of victim blaming also extends to the terms used. The Internet Watch Foundation outlines that they are always careful to contextualise what “self-generated” content means because the term itself can serve to further reinforce a culture of victim blaming. “When we refer to ‘self-generated’ I always have to make it very clear, we’re following what is set out in the Luxembourg guidelines, it can be quite a problematic term. It seems to imply complicity on the part of the victim, so just to make it really clear, when we’re talking about self-generated content we’re really talking about remote offending. So the offender isn’t physically present but is tending to be directing or coercing a child into producing sexual content which they are then capturing and saving remotely”. The IWF argues that we need to shift the narrative to find better ways of protecting young people to ensure they feel able to speak up, seek help and that their recovery is supported because “we sometimes get feedback from law enforcement and parents will come to us and they will say they’ve reported an incident that’s occurring to the police and they’ve had some sort of response along the line of, “well, they’ll learn not to do that again.” So in some way this is the victim’s fault. And I think we need to shift that whole narrative around, this is a normal part of human interaction and, yes, unfortunately sometimes regrettable things occur. But shifting that narrative rather than putting everything on potentially the victim”.

The IWF identifies another difficulty with terminology such as “self-generated”. They explain that alongside putting the emphasis on the victim, it “doesn’t at all indicate the nature of the risk for anyone who is in a caring responsibility.

‘Self-generated’ means very little to parents, carers, teachers, and other professionals. If we’re to prevent ‘self-generated’ child sexual abuse instances, then we could start with using language which in some way indicates a risk factor and resonates with parents. (IWF)

Multiple studies are advocating that the best way to protect children is to have regular conversations within the family unit – whatever that family unit looks like – about their online life. We need to give family units simple, clear and everyday language in order to have successful conversations.”

13

DEYP

Report

Summary

4. Online Safety: Outdated Education?

The experts we interviewed recommended that external specialists are commissioned to deliver online safety education; resources are designed to be inclusive; and that online safety education is delivered offline.

Lorin LaFave (Breck Foundation) recommended online safety is delivered by external professionals who apply their learning to real life experiences, she argues “it’s more engaging to hear an outsider, to hear a different story […] you remember it more. Otherwise it blends in with all of the other days of learning.”

Kate Burls reflected on the difficulty of creating resources that are inclusive. One way CEOP has attempted to create more diverse resources is to move away from telling a single story, for example they utilise a chat between two people unfolding and leave the identity of those chatting ambiguous, so the focus is on how the two people are communicating with one another.

Daisy Kidd explained that for Tactical Tech they consciously chose to create online safety resources that are designed to be delivered offline “having something that takes children away from the screens […] seems like a very important decision”, but she also noted that they are uncertain whether offline resources will resonate as well with young people and that it might be better to have short content on a social media feed.

Our research revealed there were different ideas about how online safety education should be delivered, but overall many of the experts we spoke to had reached the conclusion that “online safety” is an unhelpful term that results in young people “switching off” from the educational messages they are receiving because they do not consider it relevant to their experiences.

The CEO of Parent Zone and head of the Parliamentary Digital Resilience Working Group Vicki Shotbolt emphasised the importance of not using this term and the need for an educational change: “I think the first thing I’d do is not call it online safety in schools. I think as soon as it gets out of that language and stops being online and keeping children safe in education, or being part of the computing curriculum, or even part of relationships and sex education.

14

Our research has revealed that responsibilising can serve to enhance vulnerabilities and that some of the historical language used when discussing online safety has reinforced a culture of victim blaming. This has only served to further alienate children and young people from potential sources of support.

DEYP Summary Report

And until we get there I don’t think we’ll have got it right, in the same way I don’t think we’ve fully embraced digital as a societal change, we haven’t yet fully embraced it as an educational change.”

A number of professionals recommended that assemblies or workshops are not labelled online safety education. For example, Lorin LaFave from the Breck Foundation asks not to be introduced when she is invited to deliver a session in a school: “If you tell them they’re gonna get another boring Internet safety message they’re just gonna close off. So I would rather people introduce me as, “Lorin’s going to come and talk to you about her son Breck.” Alan Mackenzie from AACOSS described a similar experience when delivering online safety assemblies: “if you stand in front of an assembly of Year 9s and say you’re gonna have an e-safety talk, you’ve lost them already... the eyes are closed, the shutters are down... But if you say you’re gonna talk about something else and then bring aspects of online safety into that, you’ve got their attention, and they can be quite interested.” Both LaFave and Mackenzie teach online safety using real life examples and experiences and they try to separate their work from negative associations with the term.

The term online safety was also found to be unhelpful for engaging parents. Adrienne Katz, Head of Youthworks recommended:

“the first thing about parent sessions is not to call them ‘online safety’ - to call them something else, ‘the Rights of your child online,’ or something completely different, and then they turn up. The title’s the killer.”

Mark Bentley for LGfL referred to online safety itself as a potential “thought barrier” that can be undermining because young people do not perceive there to be a difference between their online and offline lives and as such consider the term irrelevant or separate to their experiences on devices: “I did a Year 8 focus group where we were talking about all the online things they do and a girl told me “I don’t go online; I just go on

YouTube and Snapchat.””

Bentley also argued that the term “resilience” was problematic because it places the onus on young people building up resilience to things that they should not need to be resilient to. He suggests that “instead of expecting young people to improve their resilience we should fashion a child-first Internet with the safe spaces our children and young people deserve, through a mix of education, industry action, legislation and regulation, and with the Online Safety Bill moving through parliament now, we are moving in the right direction.”

15

online anything, actually, and acknowledge that there is an element of digital in every single subject that they teach […] It’s such a fundamental part of every

(Vicki Shotbolt, Parent Zone)

DEYP Summary Report

(Adrienne Katz, Youthworks)

We have to get to the point where we stop talking about online safety and single subject, it should just be being taught by everybody.

Acknowledgements ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge and thank all the contributors to this project who kindly gave their time and invaluable knowledge and experience. Whilst it is not possible to reference all contributors, every interview is integral to the paper.

We wish to extend our thanks to the contributors listed below¹, and we also wish to extend our sincere thanks to those who chose to remain anonymous.

Adrienne Katz, Youthworks

Vicki Shotbolt, Parent Zone

Lorin LaFave, Breck Foundation

Mark Bentley, LGfL

John Carr, OBE, UK Children’s Charities’ Coalition on Internet Safety

Kate Burls, CEOP, National Crime Agency

Rebecca Avery, The Education People

Peter Watt, Family Support

Rhiannon-Faye McDonald, The Marie Collins Foundation

Annie Mullins, OBE, The Trust and Safety Group

Claire Levens, Internet Matters

The Internet Watch Foundation

Alan Mackenzie, AACOSS

Alan Earl, AACOSS

Daisy Kidd, Tactical Tech

This research project is funded by the University of Warwick, Economic and Social Research Council Impact Acceleration Account.

Designed by Nifty Fox Creative, 2023.

¹Please note the organisational affiliations were correct at the time of interview, and some affiliations may have changed.

17

DEYP Summary Report

Bibizadeh, Roxanne, Rob Procter, Carina Girvan, and Helena Webb. “Digitally Un/Free: The everyday impact of social media on the lives of young people.” Learning, Media and Technology (Under review).

Brewster, Thomas. “Child exploitation complaints rise 106% to hit 2 million in just one month: Is Covid-19 to blame?” Forbes, 24 April 2020,

Donovan, Louise and Corinne Redfern. “Online child abuse flourishes as investigators struggle with workload during pandemic: In four weeks, the amount of child abuse materials being removed from the internet has plummeted by 89 per cent.” The Telegraph, 27 April 2020,

NPCC (National Police Chiefs’ Council). Missing Exploited Children During Covid-19 Lockdown. Report 6 April 2021,

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). Children in a Digital World: The state of the worlds children 2017. Report, December 2017, UK.

United Nations 2020. Policy Brief: Education During COVID-19 and Beyond. Report, August 2020.

18

DEYP Summary Report

Works Cited WORKS CITED

Dr Roxanne Bibizadeh & Prof. Rob Procter

University of Warwick

Dr Roxanne Bibizadeh & Prof. Rob Procter

University of Warwick