8 minute read

Case Study: Historic Fourth Ward Park; Reimaging Parks as Stormwater Infrastructure

Case Study: Historic Fourth Ward Park, Atlanta, GA; Reimaging Parks as Stormwater Infrastructure

Splash Pad at Historic Fourth Ward Park, Atlanta, GA; Image by Christopher T. Martin

Advertisement

The function of Historic Fourth Ward Park (HFWP) can be outlined rather simply, the site serves as a neighborhood park and stormwater detention area. However, the history of the site and complexity of its design and function has made the park a new jewel of the Atlanta park system. The site is located adjacent to the Atlanta Beltline which spurred redevelopment interests in the Old Fourth Ward area including development of the park.

The location was first known in the 1860s as Ponce de Leon Springs, a representative name for the site otherwise known as John Armistead’s beech grove which was two miles from downtown Atlanta. The early owner took advantage of the springs as a revitalizing source by charging 10-cents per visit and included transportation via an omnibus from downtown. It was not until the 1930’s that the area retained the name ‘Old Fourth Ward’ when the number of wards were reduced across the city. In 1903, the Ponce de Leon Amusement Park opened on the northern area of the future park site and included a theater, merry-go-round, penny arcade and restaurants. Adding to the attraction of the area, the Ponce de Leon Ballpark opened in 1907 to the north of the current park. The ballpark hosted the Atlanta Crackers and Black Crackers until the 1960s, both predecessors to the current Atlanta Braves. Much of the current park area served as parking lot over the next several decades.

Further development included the Sears Roebuck’s Southern Regional Distribution Center which was built over the springs. The 2.1 million SF facility was the largest brick building by size in the Southeastern U.S. and operated until 1987. Upon opening of the facility, Sears hosted a farmer’s market on site until the late 1940s as a means to showcase the area's produce and crafts and draw shoppers to the large complex. Between the 1960s and 1980s the demographics of the Old Fourth Ward changes dramatically, losing population, from a peak of 21,000 to only 7,000 by the 1980s. Increased crime, vacant buildings, and a cultural shift from urban shopping to suburban malls, brought about the end of the Sears Roebuck facility.

In 1989, the City of Atlanta purchased the facility for $12M and operated it as ‘City Hall East’ until 2001. Housing the city’s police, fire and 911 operations, the building was only 10% used. With rising maintenance costs and on-going issues with water damage from the springs, the City sold the facility for $27M in 2010 to Jamestown Properties which launched Atlanta’s largest reuse project in history. The $300M redevelopment of the National Register of Historic Places building opened in 2014 as Ponce City Market and included 259 apartments and over 1M square feet of retail and commercial office space.

As a catalyst to the redevelopment of Ponce City Market, Bill Hisenhauser, a local stormwater activist, gathered a group of local residents in 2003 to discuss options for improving the stormwater issues of the Clear Creek basin, which includes the northern areas of the park. Tying back to the federal consent decree against the City of Atlanta to improve sewer and storm water issues, the group developed a concept that centered around development of a new 35-acre park which included a sustainable storm water detention pond. Progress on development of a future park quickly took off .

By 2005, Mayor Shirley Franklin formed the Beltline Coalition and a Tax Allocation District, similar to a Tax Increment Finance (TIF) district. Working with the Trust for Public Land (TPL), the first ten acres were purchased and plans for an additional seven acres completed. In 2006, the City of Atlanta established the Atlanta Beltline, Inc. (ABI) to lead development of the 22-mile corridor adjacent to the future park site known as the Beltline.

One of the first actions by the ABI was to establish the 17.5 acre Old Fourth Ward site as the first park of the larger Beltline project. In alignment with ABI, a community-based planning group was formed which included area developers with interest in the park. The Park Area Coalition (PAC) worked directly with ABI to develop new plans for the park site, reduced from the original 35-acres and also secured a $8M donation from the Woodruff Foundation for additional land acquisition.

By 2008, the Historic Fourth Ward Park Conservancy was formed as a non-profit entity to focus on the development, enhancement and maintenance of the park. In early 2009, ABI completed a redesign of the park and developed new phasing priorities. A team lead by EDAW/ AECOM and Arcadis developed a series of options for the park based upon local community input. The resultant Atlanta Beltline Master Plan: Sub-Area 5 for the Historic Fourth Ward Park included recommendations for phasing, materials, and program, therefore establishing a set of design guidelines for the future park.

In late 2009, the first phase of construction began and included a 2.5-acre lake and amphitheater located in the central portion of the park site. Within two years, Phase 2 of the park development began and included a splashpad, playground and skate park located in the southern area of the park. Future phases include acquisition and construction of additional parcels which linked two separate areas of the park in the southern portion together and create a larger 30-acre park.

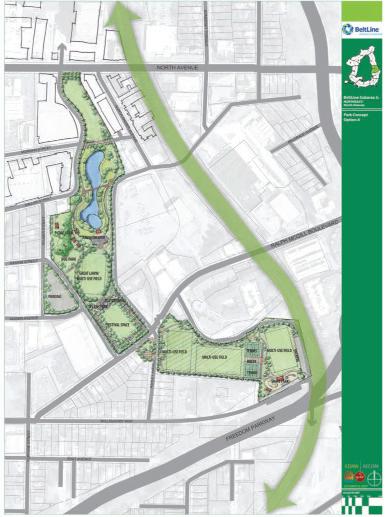

Concept 'A' for the Historic Fourth Ward Park adopted in March, 2009

Concept 'A' for the Historic Fourth Ward Park adopted in March, 2009: Atlanta Beltline, Inc., developed by EDAW/AECOM, Arcadis and ADP.

Areas of Innovation:

2003 aerial of the Old Fourth Ward Park area.

2003 aerial of the Old Fourth Ward Park area. Courtesy of Historic Fourth Ward Park Conservancy.

2018 aerial of the Old Fourth Ward Park area.

2018 aerial of the Old Fourth Ward Park area. Courtesy of Historic Fourth Ward Park Conservancy

Storm Water: Initially the City of Atlanta Department of Watershed Management estimated improvements needed within the Clear Creek basin to solve storm water problems with a cost between $40-70M. The Department planned to add an overflow tunnel adjacent to an existing sewer trunk and separate sanitary and storm waters to increase capacity from a two-year storm event to a 100-year event. By 2003, influenced by ideas that emerged from the group lead by Bill Hisenhauser, a park centered around a storm water detention pond evolved and was believed to achieve the same goals with estimated costs of only $23M. Far less than earlier gray engineering solutions.

At the center of the park, a two-acre stormwater detention pond was constructed by the City’s Department of Watershed Management. The pond serves as the primary stormwater run-off detention area and has a capacity to retain 26-acre feet of storm water. As a redundant safety feature against flooding, the pond is connected to the Clear Creek truck sewer. Overall, the site has the capacity to detain stormwater flow for a 100-year storm event within the 800-acre drainage basin, reducing the peak flow of the Highland Avenue Combined Sewer Trunk. Two horizontal lines of river pebble in the granite detention basin walls mark water levels achieved by different size rain events. Flow into the Highland Avenue trunk is made by a 24” line which slows discharge. Backflow preventors were installed to ensure sanitary sewer water would not enter the park pond.

In addition to the stormwater detention capacity of the park, the existing springs produce over 425 gallons of water per minute which is used for irrigation throughout the park. A ten-foot waterfall and a stone water cascade were developed to help aerate the recycled water contained in the pond.

Though the design of the park includes a year-round detention pond with scenic views, a top request during public engagement, the water is not suitable for swimming or drinking. To discourage contact with the water, plantings include the use of prickly species to prevent human and pets from entering the water. Additionally, most areas near the pond include barriers and cable railing. The lower walkways are designed to be temporarily submerged when a 100-year storm event occurs.

Partnerships: A key contributor to the success of the park’s development were the partnerships and support groups formed with the expressed common goal of seeing the park realized. The initial Park Area Coalition provided pro bono services to identify and negotiate the purchase of the first parcels for the park by TPL. The PAC had early support of City Council and the Mayor which resulted in quicker implementation. Adjacent developers had long sought the city to take action in solving the stormwater issues within the Clear Creek basin. Redevelopment in the Historic Fourth Ward was being held back compared to the rest of the city due to high risks of flooding. By supporting the development of the park as a stormwater solution, City Council and the Mayor were supporting redevelopment needs.

With developer support, the city was able to realize several of its goals for the neighborhood: historic preservation, job creation and redevelopment. By 2016, the Old Fourth Ward neighborhood had already received over $400M in new private investment immediately adjacent to the park, representing an 800% return on investment for the city. Additionally, the $300M redevelopment of the Ponce City Market represented the largest private investment in a reuse building in Atlanta.

Sustainability First: Starting with initial contributions from Bill Hisenhauser and the local residents group, the idea of the Historic Fourth Ward Park centered around a sustainable solution to the local stormwater problem. Begun with a typical approach to providing increased stormwater capacity and meeting the terms of the federal consent decree, the project grew to include park spaces, native plantings, scenic water elements and walking paths, resulting in genera ng adjacent revitalization, high-density urban development and an innovative solution for a combined sewer overflow problem. This approach to solving storm water problems has now become a new standard for the City of Atlanta Department of Watershed Management to maximize infrastructure investment and focus on environmental, economic and social sustainability.

Temporary flooding at Historic Fourth Ward Park in 2014

Image by Historic Fourth Ward Park Conservancy.

The City of Atlanta and ABI received a Gold Envision Award from the Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure in 2016 for the project. The award recognizes the project’s unique approach to solving a common urban storm water problem while improving community livability in Atlanta. In addition to the stormwater improvements, the award recognizes the resource conservation of the project with use of native plantings and a self-sustained irrigation system with a 20,000 gallon cistern, along with the tremendous economic benefits the project has provided to the surrounding neighborhood.

In all, the park is the recipient of over a dozen awards from such organizations as the American Council of Engineering Companies, American Society of Landscape Architects, the Urban Land Institute, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the National Brownfield Association.