5 minute read

The Shipman Inquiry

be vaccinated, as there would still be herd immunity. Therefore, the ‘anti-vaxxers’ that are vehemently against vaccination could refrain from being vaccinated, which would diminish the problem of enforcement and what to do with those who don’t comply with the rules that the mandatory legislation of the COVID-19 vaccine would bring.

Overall, the government does have the right to make the vaccine mandatory, as they intervene on other matters of health in the best interests of the population. If necessary, mandatory legislation would be most effective as a last resort, in case not enough people take the vaccine. It would be far more sensible to first use methods of persuasion and advertisements to encourage rather than force people to take the vaccine, as this works better than simply fining people, or ultimately even sending them to prison.

Advertisement

By Mukampikai Sathees, Year 12 North London Collegiate

The power that a doctor holds when entrusted with the lives of their patients can lead them to develop a ‘God complex’ in which they believe that they have the right to decide who should live and who should die. This was the case with Harold Frederick Shipman, an English general practitioner who is believed to be the UK’s most prolific serial killer.

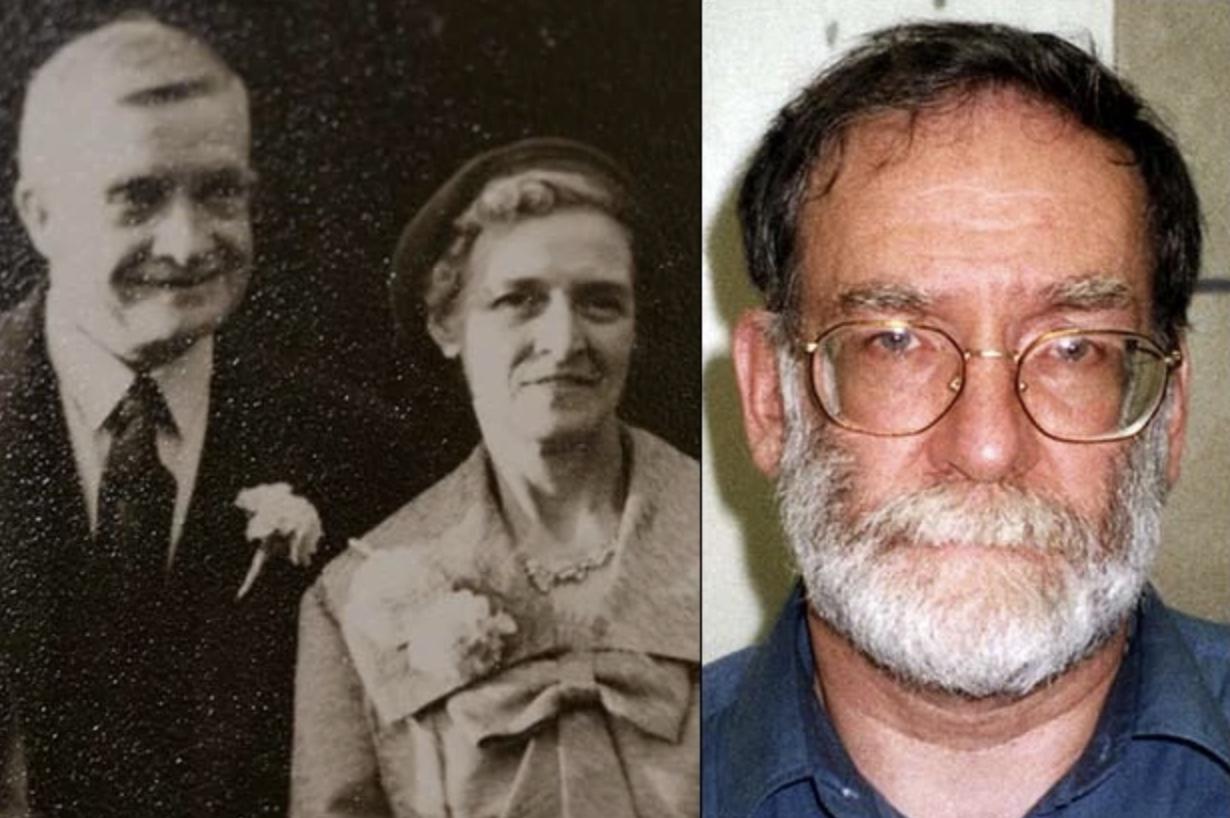

Shipman was born in January 1946 in Nottingham. He was particularly close to his mother and so losing her to lung cancer when he was just seventeen affected him severely. It is believed 49

that through his career, Shipman attempted to process his trauma by re-living the last year he spent with his dying mother.

After graduating in 1970, Shipman began working as a preregistration house ranks officer at the Pontefract General

Infirmary. The infirmary saw a higher than usual death rate during Shipman’s training period and nurses recalled seeing empty injection packets lying in the rooms of the deceased

patients. Although no-one questioned it at the time, if any of these deaths were murders, they lined up with Shipman’s later modus operandi (often shortened to M.O., it is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally). Shipman may have injected his patients with morphine, remembering how it eased his mother’s pain, despite her terminal condition, and an accidental overdose may have shown him that morphine could be used to kill without consequence and thus permanently remove their pain.

Shipman had tried morphine himself and claimed he ‘didn’t care for it’. However, he did develop a pethidine addiction whilst working at the infirmary and so when offered a job as an assistant general practitioner in 1974, he went out of his way to handle them by offering to re-organise records and dispose of outdated pharmaceuticals. He quickly realised no one else was tracking the disposal of the pharmaceuticals and so he began overprescribing pethidine to his patients so that there would always be excess pethidine for his personal use. A lethal dose of pethidine to someone with no tolerance is 500mg but by 1975, Shipman was taking 600mg daily and his co-workers had no clue. However, a pharmaceutical company noted the vast amount of pethidine they were supplying to his workplace and contact the Home Office. The investigation led to Shipman and although all signs suggested pharmaceutical abuse, he was left with a warning. However, his addiction continued, and the side effects grew worse. In 1975 he was diagnosed with idiopathic

epilepsy. By September 1975, his colleagues confronted him as they believed he was guilty of theft, forgery, and drug abuse and when he admitted, he was forced to resign and enter a rehabilitation centre. The authorities were also alerted and Shipman was charged with 82 criminal counts for unlawful drug possession and prescription forgery. He plead guilty to 8 and was fined £600 and asked to pay compensation to the NHS. However, his medical licence was not revoked as there was no evidence his patients had been harmed by his drug abuse and he had appeared to have made a full recovery after just three months in the rehabilitation centre. In 1976, his case was fully closed.

In October 1977, he began working again as a GP in Hyde. The only remaining consequence of his drug abuse was that he was not legally allowed to carry controlled substances on his person.

Just 10 months into his new job, Shipman made his second confirmed murder, most likely by morphine overdose. He listed the patients cause of death as coronary thrombosis and in their grief, the family never questioned it. Shipman also listed the deaths of many of his other elderly patients as pneumonia, respiratory failure, and myocardial infarction – perhaps to mislead the coroner.

He followed a distinct modus operandi. He would visit a patient at home, inject them with narcotics to ease their pain, ensure the death appears natural and then turn on the fireplace, to speed up the body’s decomposition which causes complications e.g., when assessing a specific time of death. The pattern resembled the last days he spent with his dying mother.

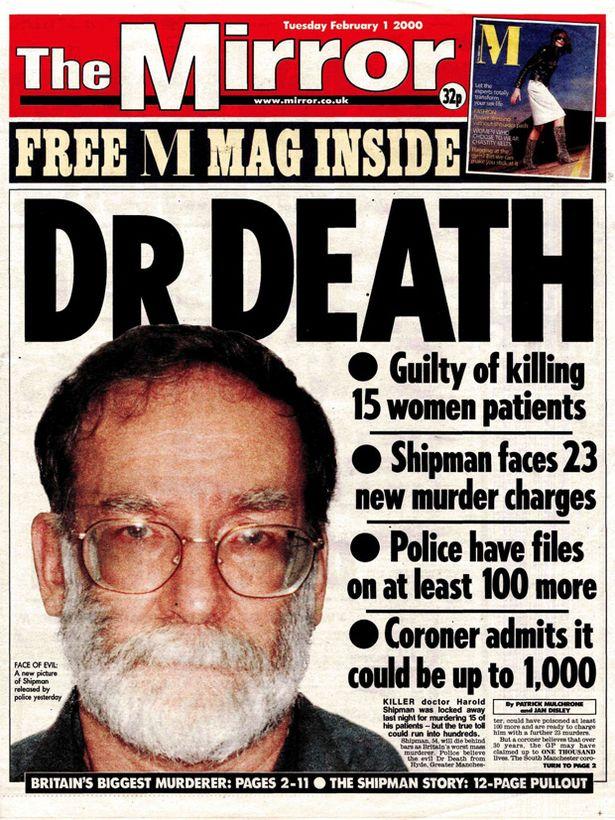

Shipman was finally arrested on 7th September 1998 after murdering 81-year-old Kathleen Grundy. Despite her age, she was in good health and Shipman’s visit was only for a routine blood test but instead of drawing blood, he injected a lethal dose of morphine. When she was found dead the next morning, Shipman certified that she had died of old age. However, her daughter grew suspicious when she found that her mother’s will had been changed and now left £400,000 to Shipman. Mrs Grundy’s body was later exhumed, and morphine was found in her system. Another eleven bodies were also exhumed, and Shipman was charged and convicted with 15 counts of murder and 1 of forgery.

On 1st February 2000, the Secretary of State for Health announced that an independent private inquiry would take place 53

in Shipman’s activities. The inquiry was chaired by Dame Janet Smith DBE and its findings were released in a total of six reports. It investigated 618 deaths took approximately 2500 witness statements. The report confirmed that Shipman had killed at least 215 but possibly as many as 260. In January 2004, he was found hanging in his cell in Wakefield Prison.

Law X Crossword!

Test how much you are able to remember!