2 minute read

LOOKING AT HAPPINESS AND VIRTUE THROUGH A STOIC AND EPICUREAN LENS

ByImaan

Background of Stoicism & Epicureanism:

Advertisement

Stoicism was founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium in around 300 B.C.E and has flourished as a major philosophical school of thought: it moved to Rome during the period of the Empire, where it subsequently influenced numerous Emperors, the foundations of Christianity and many major philosophical figures. Epicureanism sought its foundations at a similar time period to Stoicism; it revolves around the teachings of Epicurus, who lived from 341-270 B.C.E. Both Stoicism and Epicureanism preach that happiness is the central goal of life, however, they differ vastly in their approaches to achieving such happiness.

Stoicism:

Like many Hellenistic schools, Stoicism centres much of its philosophy around Aristotelian ethics and the idea that Eudaimonia is the telos (end goal) of every human life. Stoics equate this Eudaimonia with the idea of pleasure; Zeno claimed that the highest pleasure was “a good flow of life” and “living in agreement [with nature]”. By answering the question “what is good for me?”, one can begin to see ethics from a Stoic perspective, as surely what must be genuinely good for a person ensures their happiness. Hence, a Stoic approach refutes a purely hedonistic lifestyle that may risk future pleasure and even money may be regarded as a hindrance due to its corrupting influences. In fact, Stoics refer to objects such as money, which are regarded as neither good nor bad as ‘indifferents’.

The only things that Stoics regard as truly good are virtues (in a truly Aristotelian fashion), the four Cardinal Virtues being prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. Stoics accept our natural propensities in their concept of oikeiosis, which would allow for a hierarchy of preferences, with human survival needs at the base. However, as one educates themselves and philosophizes, they can begin to perfect the rational capabilities, cultivating intellectual development. This will encourage the growth of moral virtue in comparison to temporary pleasures, allowing them to access the greatest good. Thus, the Stoic pathway to be happiness is revealed through becoming a virtuous agent, which them enables them to reach Eudaimonia.

Epicureanism:

Like the Stoics, Epicurus’ ethics originate from Aristotle’s idea of a happiness as the highest good, with Eudaimonia being the ultimate goal in life. Epicurus saw the pursuit of pleasure as the pathway to this goal and distinguishes between two different types of pleasure: ‘moving’ pleasures, which satisfy a desire (e.g., eating when hungry), and ‘static’ pleasures, which is the state of satiety after fulfilling a desire. He argues that the static pleasures, which are a state of no longer being in need or want, are the highest pleasures. Epicureans, like the Stoics, would regard virtues as a necessity to aid the pursuit of static pleasure, however, whilst Stoics believe virtues to be the only means of achieving the greatest good, for Epicureans, it is simply one of many.

Epicurus equates the ultimate pleasure (and Eudaimonia) with tranquillity (ataraxia), which can be achieved through katastematic pleasure (the removal of all pain, both mental and physical). To do so, one must fulfil their necessary desires, shedding excess desires related to luxury. Hence, many interpret Epicureanism as advocating for a more hedonistic lifestyle in order to satisfy any worldly desires.

Conclusion:

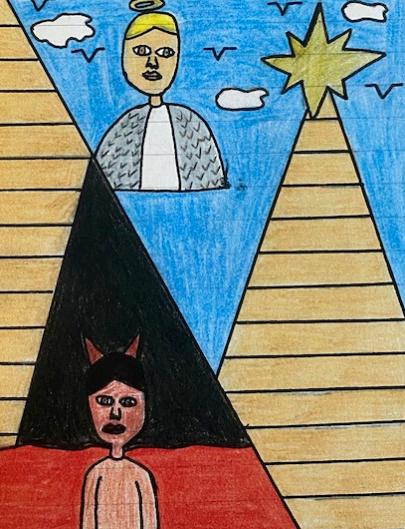

Therefore, whilst Stoics believe that there are many uncontrollable influences on every life, which they can learn to overcome through developing virtue (the greatest good in itself), Epicureans use virtue as only one of the means to shed the desires that man is naturally plagued with. Instead, an Epicurean may also seek a hedonistic lifestyle to reach pure happiness and ataraxia.