14 minute read

Smile: The Beach Boys’ Lost Great Album by Soren Eversoll

from NoFi Fall 2022

by nofidel

Smile: The Beach Boys’ Lost Great Album

Soren Eversoll

Advertisement

The Beach Boys’ Smile is perhaps the most legendary album never made. Meant to be the grand slam to follow Pet Sounds, which elevated the band from twee California surf rock into baroque pop glory, Smile was never released and marked the beginning of the end for the band—The Beach Boys would release eighteen more albums, though none would reach the level of artistry they’d achieved in the sixties. Exacerbated by inter-band tensions, fame, drugs, and the pressure facing frontman Brian Wilson to follow up on what had already been declared a perfect album, the Beach Boys never fully escaped the album’s specter. It would not be until 2004 that demands from fans prompted Wilson to re-record the album with original collaborator Van Dyke Parks and release Brian Wilson Presents Smile; archived sessions from the original studio recordings would be released in 2011. Never before has an unreleased pop album become the subject of two retrospective albums, of rabid obsession, of such total rock fetishism. Why?

Much of The Beach Boys’ action in the early to mid-sixties was inexorably linked to the orbit of The Beatles. The band ushered the new British Invasion into America that paved the way for The Who and The Rolling Stones and, with the release of Rubber Soul in 1965, transformed the studio album from what was meant to be a faithful reproduction of the live act into an art form all its own. Music journalist Steve Turner described it as starting “the pop equivalent of an arms race’. Upon hearing Rubber Soul Wilson became determined for his group to release their own work that relied less upon the success of singles than the strength of the album as a cohesive whole, telling his wife Marilyn that he was going to make “the greatest rock album ever made’.

Beatles or not, Wilson’s desire to musically transcend the surf rock cliches The Beach Boys had ridden to popularity on were, by 1965, long-stewing. It had soon become apparent that Brian, brother to Beach Boys Dennis and Carl Wilson, cousin Mike Love, and childhood friend David Marks, had a special attunement to music that his bandmates lacked. As a child, Wilson demonstrated an exceptional talent for learning by ear, able to recite verses as a baby that his father had sung for the first time only moments before. Wilson also had perfect pitch and a voracious appetite for learning new instruments, even though he was completely deaf in his right ear due to a childhood blow to the ear from a lead pipe held by a neighborhood boy.

Art: Aviva Sachs

Recording sessions for Pet Sounds began on July 12, 1965, and ended on April 13, 1966. During this time Wilson took full creative control of the studio, often demanding endless takes from the studio musicians to achieve the sound he wanted, relegating his bandmates to the backseat. No sonic possibility was off limits—at one point, Wilson asked the producer if it would be possible to bring a horse into Sunset Boulevard’s Western Studio to record the coda to “I Know There’s An Answer’. Harpsi-

chords, string quartets, French horns, the Theremin, soda cans, and found sounds all found their way into the album’s final mix. Tensions over Brian’s sole leadership arose, particularly between Wilson and Mike Love, who felt the band was moving in an unsellable, overtly-hippie direction.

While it did not commercially sweep upon its American release, Pet Sounds was quickly labeled an artistic triumph. This was particularly noticeable in British media—one advertisement labeled it: “The most progressive pop album ever!” This sort of hype was accentuated by an aggressive marketing campaign spearheaded by the former press officer to none other than The Beatles themselves, Derek Taylor. In an effort to brand The Beach Boys as legitimate artists alongside John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Bob Dylan, Taylor frequently circulated the phrase “Brian Wilson is a genius’, when interviewed by the press. In a 1966 article for the British magazine Melody Maker titled “Brian, Pop Genius!” Taylor depicted Wilson as a musical marvel, drawing comparisons to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven: “This is Brian Wilson. He is a Beach Boy. Some say he is more. Some say he is a Beach Boy and a genius. This twenty-three year-old powerhouse not only sings with the famous group, he writes the words and music he then arranges, engineers, and produces…. Even the packaging and design on the record jacket is controlled by the talented Mr. Wilson. He has often been called ‘genius’, and it’s a burden’. Pet Sounds sales soared in the U.K., and by the end of 1966 London-based magazine, New Music Express’ reader’s poll ranked Wilson as number four in its list of world music personalities.

Wilson was emboldened by the success. Now ensconced in press, he declared that the next album would wildly improve upon the ideas started in Pet Sounds, what he labeled a “teenage symphony to God’. The album was originally to be called Dumb Angel, then changed to Smile. At some point in 1966, Wilson met songwriter Van Dyke Parks at a party in Los Angeles. Parks had recently moved to the city and was largely working as a producer for bands like The Byrds and The Mojo Men. Impressed by his eloquent manner of speaking, Wilson asked if he would assist him as his new lyricist. Parks agreed.

Between July and September of 1966, Parks and Brian Wilson in the studio, 1976 Wilson camped out in the latter’s Beverly Hills home writing songs. Recording sessions soon began in Pet Sounds’ Western Studio with demos for the song “Wind Chimes’. No longer touring with the rest of the band, Wilson had developed a posse of talent execs, publicists, singers, and reporters who became fixtures at his home and in studio sessions. Drugs, particularly the amphetamine Desbutal, were ever present—to prepare for the album Wilson had bought about two thousand dollars worth of cannabis and hashish, equivalent today to about $17,000. One article reported that he had constructed a hotboxing tent in what was once the dining room and a sandbox under the grand piano in his living room. The fixture of the press’ depiction of Wilson was centered around his identity as a reclusive genius, as America’s homegrown response to McCartney and Lennon. Smile became one of the most discussed albums in the rock press, projected for a release in December of 1966. Derek Taylor continued to give interviews and anonymously submit articles to publications—in one, Los Angeles Times West Magazine described Wilson as “the seeming leader of a potentially revolutionary movement in pop music’.

recording of the song was a microcosm of the experimental approaches Wilson was adopting for Smile. Pop music in the sixties was commonly recorded in a single take—in “Good Vibrations’, Wilson took sections from different recording sessions and forced them together into a single song, a method later known as tape splicing. This is evident in the song’s dramatic switches in mood and key. Dubbed a “pocket symphony” by Taylor, “Good Vibrations” boasted propulsive cellos, the Electro-Theremin, and the jaw harp. It was emblematic of the studio as the principal instrument, of editing becoming more important if not equal to recording. Wilson produced over ninety hours of tape to get “Vibrations” the way he wanted it, costing Capitol Records tens of thousands of dollars in the process. Upon its release, it became the band’s third number-one American hit and the first in Great Britain. In December, Capitol ran an ad in Billboard: “Good Vibrations. Number One in England. Coming soon with the ‘Good Vibrations’ sound. Smile. The Beach Boys’. Another ad in TeenSet ordered: “Look! Listen! Vibrate! SMILE!….other new and fantastic Beach Boys songs…and…an exciting full color sketch-book inside the world of Brian Wilson!” In an interview following the single’s release, Beach Boy Dennis Wilson told Hit Parader: “In my opinion, [Smile] makes Pet Sounds stink. That’s how good it is’.

With Smile, Wilson wanted to produce a response to what he saw as the increasingly-anglicized state of popular music. By 1966 the British Invasion had fully come to dominate the popular consciousness. In response, Wilson and Parks wanted to create songs that were distinctly American, that embodied a sort of early American ethos and slang, and that drew their inspiration from doo-wop, ragtime, gospel, and cowboy movies. This necessitated the incorporation of traditional American instruments like the tack piano, harmonica, fiddle, banjo, and steel guitar. Wilson simultaneously viewed the album as a “return to the pre-grammatical, non-linear, and analogical thinking of early childhood— they are the artefacts of play’. Songs were intentionally made to be silly. In response to this Wilson later said: “We wanted Smile to be a totally American article of faith…it seemed the best way to do that was to be counter-counter-cultural’. Wilson constantly took in new inspirations, ranging from astrology to the occult to the book The Act of Creation by Arthur Koestler. Material for Smile underwent daily re- visions and rearrangements; because of the con- stantly shifting nature of the album and the ex- tensive use of tape splicing, it became unclear where some songs ended and others began. The content of the songs varied wildly. “Heroes and Villains’, which devoted thirty studio session days and cost an estimated $40,000 before Wil- son scrapped all recordings, was inspired by the Old West. “Cabin Essence” told the story of the Union Pacific in an abstract, rambling fashion. Mike Love objected to many of the song’s lyrics, believing them to be thinly-veiled referenc- es to drug culture. “Do You Like Worms?” con- cerned the colonization of the American conti- nent. Worms are mentioned nowhere in its lyr- ics. One stanza goes: “Bicycle Rider, just see what you’ve done, Done to the church of the American Indian!” “Bicycle Rider” refers to Bicycle Rider Back playing cards printed in the 19th century. This stanza is followed by lyrics in Hawaiian delivered in near-demonic chants, translated to: “Thank you, thank you very much, it’s so late’. This was meant to repre- The Beach Boys, 1963 sent a sarcastic response to

colonists, having already expanded and conquered America far beyond repair. At one point Wilson conceptualized a four-part movement titled “The Elements’, with each song representing air, fire, earth, and water. To record “Fire”, Wilson brought fire helmets and a bucket of burning wood into the studio, filling the room with smoke. A few days after the initial session a building across the street from the studio burned down. Convinced his music had caused the fire, Wilson discarded the song.

The scrapping of “Fire” marked the beginning of Smile’s recording issues. The Beach Boys had entered into a lawsuit with Capitol Records over payment disputes. This dragged on for months and frayed relations with the label—at one point, a Beach Boys single was released by EMI without the band’s consent. Wilson was heavily under the influence of Desbutal, which caused paranoia, enhanced-ego, and horrible crashes. Wilson would later be diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and while his bandmates would attest that his symptoms were almost totally absent while recording Smile, some delusional traits and fixations began to show themselves. The Beach Boys were growing frustrated with their frontman’s eccentricities and the seemingly endless nature of the project, leading to intense confrontations in the studio that gave Wilson severe anxiety attacks. This was only exacerbated by the near-constant coverage in the press following Pet Sounds. Wilson had already been a perfectionist, but declarations of the project’s genius prompted him to become even more uncompromising in the studio, burning through money and frustrating his musicians and collaborators. He was also loaded. Dennis Wilson recalled: “Drugs played a great role in our evolution but as a result we were frightened that people would no longer understand us, musically’. Bandmates like Mike Love believed that the bizarre Americanized concept album had gotten too weird, too avant-garde. The excesses of the studio that had once seemed like freedom were now pits of inactivity. Capitol pressured for a new single to replace “Good Vibrations:” “Heroes and Villains” became the object of Brian’s obsession, leaving other tracks on the back burner. In February, Wilson and Parks began to clash over lyrical content—tired of being stuck in the middle of family feuds that he thought were of no concern to him and constantly subservient to Brian’s creative veto, Parks left the Smile project on March 2, 1966.

Wilson continued to fall into drug-addled delusion. In one episode he became convinced that a portrait a friend showed him had captured his soul. In another, after attending a screening of the movie Seconds, Wilson became paranoid that the film contained coded messages sent to him from idol Phil Spector. Wilson was preoccupied with what he perceived as competition with The Beatles—upon hearing “Strawberry Fields Forever’, under the influence of the barbiturate Seconal, he reportedly pulled his car to the side of the road and told a friend: “They did it already—what I wanted to do with Smile. Maybe it’s too late’.

Parks’ departure marked the true end of Smile. Without him, Wilson was lost in the woods of his own creation. Public expectation, which had initially heightened with the album’s ever-increasing delays, grew impatient. This marked the beginning of a shift in public opinion towards Wilson, from eccentric genius to troubled recluse; the image of Wilson that Derek

Taylor and Capitol Records had so meticulously constructed was beginning to eat its subject alive. On May 6 Wilson fully scrapped the album. The release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in June only exacerbated his feelings of insecurity. He later said: “Time can be spent in the studio to the point where you get so next to it, you don’t know where you are with it’. Wilson announced to his bandmates that all the material on Smile was now off-limits.

From June to July the Beach Boys met in Wilson’s makeshift home studio on Bellagio Road to record Smiley Smile, the official follow-up to Pet Sounds. While now considered a revolutionary work in the genres of lo-fi and bedroom pop, Smiley Smile was nowhere near as technically advanced as Smile. All vocals with echo were naturally created using Wilson’s emptied-out swimming pool; recordings were carried out with radio broadcasting equipment. To create a feeling of comradery, Wilson ceded many of his production ideas to his bandmates. When it was released on September 18, 1967, Smiley Smile peaked at 41 on the Billboard charts, making it The Beach Boys’ lowest charting album yet. “Undoubtedly the worst album ever released by The Beach Boys’, said Melody Maker. “Prestige has been seriously damaged’. NME wrote: “By all the standards which this group has set itself, it’s more than a grade disappointing’. In February 1968, a Rolling Stone article announced the album as a “disaster” Image, Billy Bratton and an “abortive attempt to match the talents of Lennon and McCartney’.

The trauma surrounding the production of Smile would cause Wilson to block all talk of the album until the early 2000s when it was finally revisited and partially recreated.

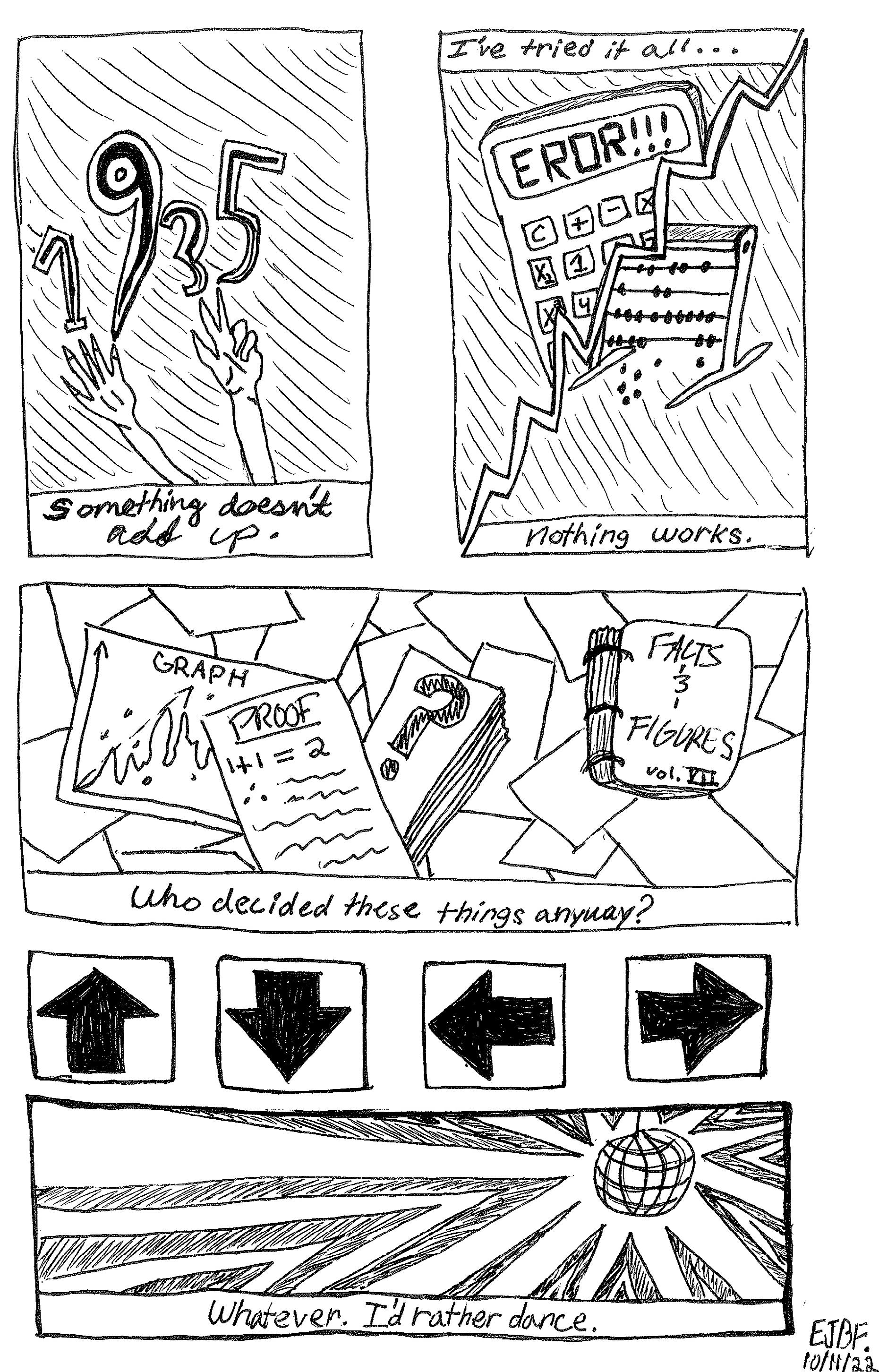

Today, it’s easier to see that the mystique swirling around Smile is less about any of the songs themselves but the potential of what they could have been. Smile has come to represent the frenzied way that members of the press and fans construct mythologies that are impossible to ever realize, that become self-sustaining in their own right, and that cease to be concerned with the music or humanity of the artist at all. When Wilson was asked in 2002 about the universally acclaimed, totemic status of Pet Sounds, even he was mystified: “It keeps going back to Pet Sounds here in my life, and I’m going, ‘What about this Pet Sounds? Is it really that good an album?’ It’s stood the test of time, of course, but is it really that great an album to listen to? I don’t know”. Wilson should know better than anyone that in the cultural consciousness music always falls short of the myth, the hype, the transformation of the artist into the genius, the album into the opus. Every human on the planet knows that the Mona Lisa is great, as is Ulysses, Citizen Kane, and Kind of Blue, without ever needing to go to the Louvre, crack open the book, or attend a screening, or play the record. These things are simply great. It is not an opinion so much as a fact. Ironically, it is this very belief that killed Smile. Wilson became so consumed with the idea of creating something great that he was prevented from finishing anything at all, paralyzed by the attention and the hundreds of thousands proclaiming that they were in the presence of a genius. The hype consumed itself.

Nonetheless, if you listen to the session recordings released in 2011, which have been remastered to be an almost impossible recreation of one of Smile’s potential final forms, it’s possible to briefly understand just how great of a pop album Smile could have been. Freed from the burdens of genius and able to flourish on its own, perhaps the music could have survived.