Isamu

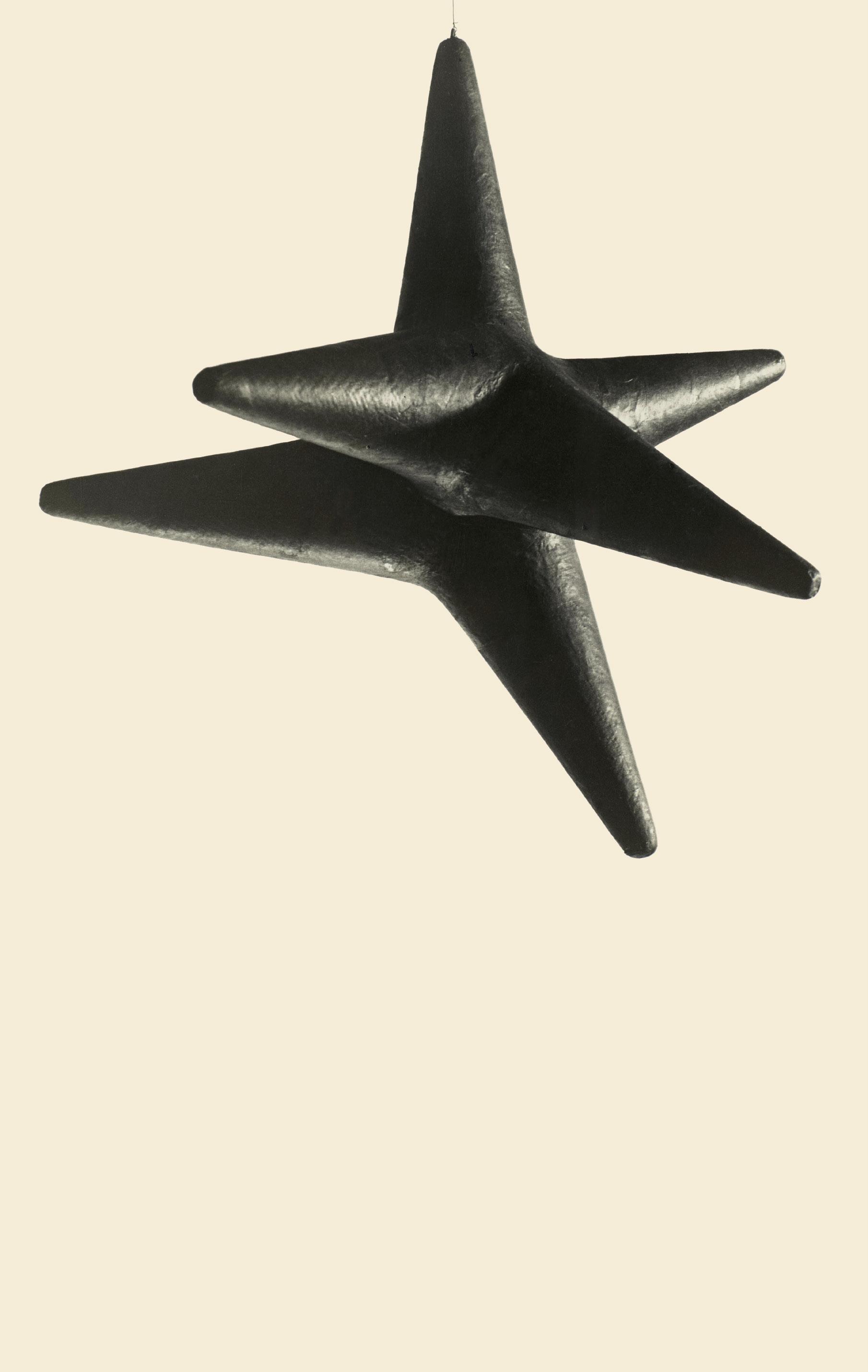

Lee Miller, Isamu Noguchi, New York, 1946. © Lee Miller Archives, England, 2023. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk.

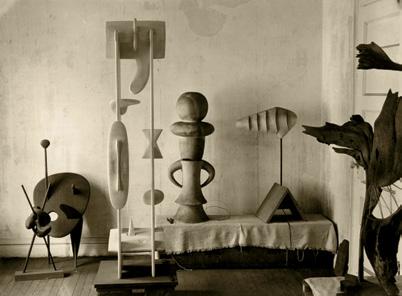

Noguchi in his MacDougal Alley studio in New York City.

Noguchi in his MacDougal Alley studio in New York City.

Isamu

Lee Miller, Isamu Noguchi, New York, 1946. © Lee Miller Archives, England, 2023. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk.

Noguchi in his MacDougal Alley studio in New York City.

Noguchi in his MacDougal Alley studio in New York City.

One day in 1945 or 1946, while alone in Isamu Noguchi’s (1904–1988) MacDougal Alley studio in downtown New York City, filmmaker and artist Marie Menken (1909–1970) moved swiftly between and around the many sculptures that crowded the space. Through the lens of a 16mm Bolex camera, she explored Noguchi’s work with close-up shots that forcefully “swing and sway” as they trace the contours, surfaces, and spaces between the sculptures.1 She would later edit this footage into a tantalizing bombardment of moving images to make her first solo film: Visual Variations on Noguchi

While many photographers captured Noguchi and his work in MacDougal Alley in still images, Menken’s riotous four-minute film stands as an utterly singular portrait of Noguchi’s sculptures in motion. Her aim, as she explained it, was to express her “excitation on seeing great works of art.”2 The film was originally silent, but in 1953 avant-garde composer Lucille (later Lucia) Dlugoszewski (1925–2000), a friend of both artists, added a cacophonous soundtrack that includes the sounds of “matches being lit, paper torn, books dropped,” paired with whispered vocalizations and crashes.3 Although there are no records of how Noguchi responded to the film in his own writings and archive, Menken recounted that “when [Noguchi] saw the footage, he was entertained and delighted. So was I.” 4

Perhaps unsurprisingly given Noguchi’s passive role in its creation, Visual Variations on Noguchi has received little more than the occasional brief mention in accounts of the sculptor’s life and work, and this exhibition marks its first screening at The Noguchi Museum. Visual Variations on Noguchi has, however, garnered significant attention in the broader history of avant-garde film. Though still underrecognized, Menken is regarded as having pioneered a handheld filmic strategy defined by ambulatory movement that proved deeply influential for a new generation of experimental filmmakers, including Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, and Andy Warhol.5 Brakhage recalled that Menken’s “free, swinging, swooping hand-held pans” in Visual Variations on Noguchi led him “to begin questioning the entire ‘reality’ of the motion picture images as related to a way, or ways, of seeing,” 6 and her camerawork “liberated a lot of independent filmmakers from the idea that had been so powerful up to then, that we have to imitate the Hollywood dolly shot.” 7

Despite this recognition, Menken’s titular subject—Noguchi—has rarely been given much weight or attention in writings about the film, and when discussed,

it is often in the context of how Menken translated, transformed, or obscured Noguchi’s sculptures.8 There is no doubt that in the quickly moving frames of Menken’s film it is difficult to make out which sculptures we are looking at, and that we lose a sense of each sculpture’s entirety. But this exhibition proposes that Menken’s treatment does not distort or turn away from Noguchi’s work, but rather honors the sculptor’s own invitation to step in. As Noguchi said, “Sculptures move because we move.” 9 Menken clearly understood this. Her film models a way of looking premised on bringing the full force of our moving bodies to Noguchi’s works.

Watching Visual Variations on Noguchi in Noguchi’s museum with many of the works that appear in the film gives new context for reconsidering Menken’s engagement with her subject. It also offers space to explore the interplay and affinity between Menken, Noguchi, and Dlugoszewski’s seemingly disparate practices, particularly their shared belief in the liberatory capacity of movement, light, and fragmentation. In examining their respective contributions to Visual Variations on Noguchi, we can also appreciate their related contentions, fueled by postwar anguish but equally resonant in our own fractured moment, that “art postpones death” (Menken), “that bewilderment is glorious” (Dlugoszewski), and that “it is out of this mess that our poetry must come” (Noguchi).10

Although it is unclear exactly when and how Noguchi and Menken first met, they are said to have connected through shared artistic circles in New York City and were collaborating on a different project around the time of the film’s

LEFT Filmmaker Marie Menken.

Photo: William Wood.

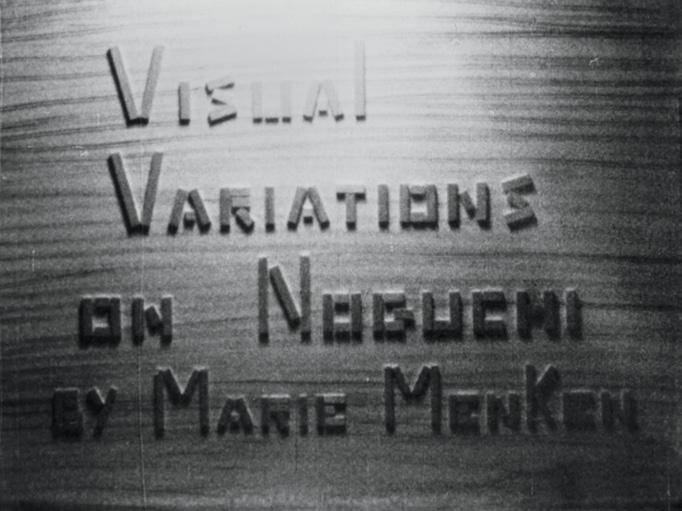

ABOVE Opening titles from Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

LEFT Filmmaker Marie Menken.

Photo: William Wood.

ABOVE Opening titles from Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

creation. Menken, the daughter of first-generation Lithuanian immigrants, grew up in Brooklyn, beginning her career as a painter before taking up filmmaking. She eventually became known as an eccentric figure of the downtown art scene who starred in some of Andy Warhol’s films in the 1960s (after reportedly teaching Warhol to use a camera) and hosted extravagant parties in her Brooklyn penthouse with her husband, the filmmaker and poet Willard Maas.11 In the mid-1950s, Menken and Maas founded an experimental film collective known as the Gryphon Group, although they had informally been collaborating throughout the 1940s. When she created her portrait of Noguchi, Menken had only made one other film, a collaboration with Maas titled The Geography of the Body (1943).12 Visual Variations on Noguchi marked the beginning of her individual experimentations with the medium.

At the time of the film’s creation, Noguchi had recently reentered the New York art scene after a harrowing period of isolation. As a New Yorker, he was technically exempt from Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced removal and mass incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast during World War II. Nevertheless, in 1942, Noguchi voluntarily entered the Poston War Relocation Center in the Arizona desert, acting on the belief that he could improve conditions by designing recreation areas and an art program. When his plan to forge a sense of community in Poston proved futile and his own freedom was jeopardized, Noguchi managed to secure a temporary leave of absence after six months in the camp and never returned. Instead, he headed for New York and settled in Greenwich Village where he mixed with a new network of American artists and expatriates who had fled the war in Europe.

Noguchi established a studio and home on MacDougal Alley, at the time an artists’ enclave, and threw himself back into his work. In Menken’s film, we can catch glimpses of the types of works that Noguchi was engaged in at the time: composite sculptures composed of found driftwood and ironwood (collected from the shores of the Pacific, from Long Island, and from the Arizona desert), self-illuminated magnesite sculptures that he called “Lunars,” and his nowiconic interlocking marble-slab sculptures (some of which he later cast in bronze). In his seven years in MacDougal Alley, Noguchi also resumed his work designing sculptures for dance, working primarily with choreographer Martha Graham but also with Erick Hawkins, George Balanchine, Yuriko, and Merce Cunningham. It was through this collaboration with Cunningham, a former Graham dancer, that his story would become intertwined with Menken’s.

According to Menken’s account, she and Noguchi collaborated on creating “special effects” for The Seasons (1947), a ballet choreographed by Cunningham with music by John Cage that had been commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein for

Ballet Society.13 Although little documentation exists on The Seasons (it was only performed five times), Noguchi is reported to have designed the costumes and scenery, which featured a long list of intricate components and effects, including red cellophane beaks that were held in dancers’ teeth, an explosion of magnesium that flashed onstage, and “designs of moving fire, snow crystals, hail, water-drops and rain [which] were projected against a transparent backdrop.” 14 Menken was involved in some capacity in the creation of these “movie backgrounds,” but nothing specific about her contributions is known as she is not credited in any official records relating to the ballet.15 Menken did not draw any particular connection between the two, but her eccentric film Hurry! Hurry! ( 1957)—in which she superimposed flickering flames over scientific footage of male reproductive cells writhing to survive, and which has been described as “a daring film ballet danced by human spermatozoa under powerful magnification”— offers an unusual but interesting clue to the spirit of the projections she made with Noguchi and the nature of their shared interests.16 A wild sense of movement in the face of death was key. It was during her work on The Seasons that Menken developed the idea of filming Noguchi’s work. She explained: “I had the advantage of looking around Isamu’s studio with a clear, unobstructed eye. I asked if I might come in and shoot around, and he said yes.” 17 What she filmed would become Visual Variations on Noguchi 18

It seems entirely fitting that part of the origin story of Visual Variations on Noguchi emerges from dance, the art of bodies in motion. Much of the dynamism of the film comes from Menken’s own moving body. In her quickly shifting frames, one can see and feel a coursing rhythm, or what has been described as “dance pulse,” propelled by the filmmaker’s improvised movements in and around Noguchi’s sculptures.19 Menken was of course not the first person to dance between Noguchi’s sculptures, but she was the first to do it with a camera in tow. For Menken this action was a way of revealing and reveling in what she described as “the flying spirit of movement within these solid objects,” and what Noguchi called their “imminent motion.” 20

Noguchi described his sculptures as “coming to life in theater,” because they were activated by their engagement with human performers; his sculptures “supply the foil upon which [people] act or they are acted upon.” 21 Speaking of Graham’s work, which, for him, successfully demonstrated his sculptures’ capacity to activate (and be activated by) movement, Noguchi explained: “The use of stage space as an asymmetrical expanse where the dancer moves—thus the viewer moves—has infinite possibilities . . . Because Martha was moving around, the audience is able to imagine themselves by moving their awareness from one spot to the next. Even though they are seated there, their imagination is not stuck there.” 22 Like Graham’s choreography, Menken’s dance with her camera models a newly kinetic way of interacting with Noguchi’s sculptures, disclosing the latent dynamism lying just beneath their surfaces. Menken, however, allows viewers to experience this play of movement in a radically different way. Rather than seeing this motion from a distance, as viewers seated in the audience would while watching Graham, Menken takes the spectator up on the stage to dance with her through and around Noguchi’s work. This visceral firstperson experience of dance is only made possible by the unusual collapse of body and eye in the lens of the hand-held camera. Thus, in a manner perhaps more extreme than Graham’s choreography, Menken’s film reveals an entire dimension of Noguchi’s sculptures inaccessible through static contemplation— and it encourages viewers to chart their own wild, nonlinear paths around them.

OPPOSITE PAGE

The Seasons, 1947. Choreography by Merce Cunningham, music by John Cage, costumes and sets by Isamu Noguchi with contributions by Marie Menken. Photo: Larry Colwell. The Noguchi Museum Archives (NMA), 01652.

LEFT Martha Graham and May O’Donnell in Graham’s Hérodiade, 1944. Set by Isamu Noguchi. Photo: Arnold Eagle. NMA, 01577.

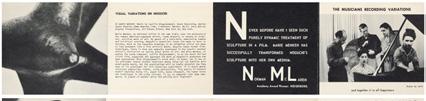

Lucia Dlugoszewski (far right), Ralph Dorazio (far left), and three unidentified musicians recording The Poetry of Natural Sound.

Gryphon Productions, brochure for Visual Variations on Noguchi, c. 1953. Erick Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski Papers, Box 21, Folder 24, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Lucia Dlugoszewski was also deeply invested in dance and likely came to know Noguchi through her connection to dancer and choreographer Erick Hawkins. In 1952, months before Dlugoszewski created the music for the film, she premiered her first collaborative work with Hawkins, who would become a lifelong creative and romantic partner. (At the time, Hawkins had recently left Martha Graham’s dance company, where he first crossed paths with Noguchi.) In 1953, Dlugoszewski became the composer-in-residence for the Erick Hawkins Dance Company, and went on to compose more than twenty-five dance scores for Hawkins, before eventually succeeding him as artistic director after his death. Over the course of this time, she worked extensively to creatively reconfigure the relationship between music and modern dance. Rejecting conventional understandings of music for dance that mandated strict coordination between movement and sound—one-to-one or “linear” correspondences of gesture and rhythm—she sought ways that these two mediums could work alongside one another (if not exactly together) to act powerfully on the imagination of audiences. Much like Cunningham and Cage, Dlugoszewski advocated for dance scores that occupied a shared time-space with the motions of dancers, but unfolded in complete isolation or non-synchronization. It was her feeling that this relationship of mutual independence left open the possibility for moments of shock, epiphany, and revelation in the minds of audience members. Navigating the aural-visual unfolding along their own imaginative pathways through the flux of sights, sounds, and gestures, they could construct their own, private connections between these phenomena.

It is in her desire to break away from linear, one-dimensional contemplation, and push audiences onto a fuzzier, more unfixed register of experience, that Dlugoszewski aligns closely with Noguchi and Menken. Dlugoszewski’s discordant musical accompaniment to Visual Variations on Noguchi, titled The Poetry of Natural Sound, is a tape collage featuring the disparate noises of percussion instruments, a manipulated grand piano, spoken and whispered words, and everyday sounds produced by five performers. Described by John Cage as a “jungle of sounds [to] explore,” it adds to the already forceful sense of delirium and movement that drives the film.23

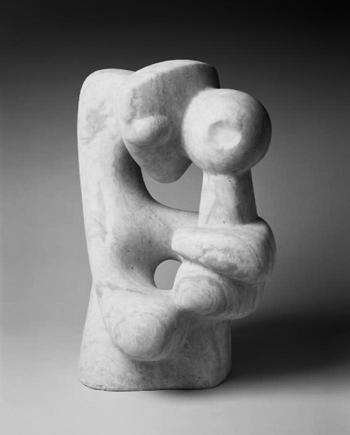

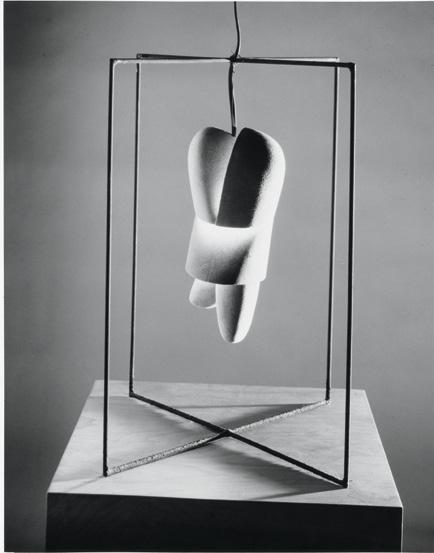

The totalizing effect of Menken’s film is a sort of dizzying abstraction. As we move with Menken, it is difficult to get our bearings. She denies the viewer any establishing shots, or wide-angle views of the space in its entirety, and we never have the opportunity to “step back” to catch a fixed overall view of any individual work. Instead, the contours and shadows of works twist, turn, and overlap, merging into a sort of contorted swell of moving fragments. Although this approach has been understood by some as compromising our vision of Noguchi’s work, Menken’s actions instead reveal and expand on the fundamental character of Noguchi’s sculptures. As he faced the new realities of a world torn apart by war, Noguchi began making works that were often composed of fragments held in tenuous balance. Many of these abstractly conjure visions of pierced and skeletal bodies (Remembrance, 1944); others feel arrested on the precipice of either destruction (Trinity, 1945) or rebirth ( The Seed, 1946). Rather than seeking the resolution or static coherence of these composite forms, in her disorienting movement and swell of twisting forms, Menken does not obscure, but rather embraces and expands the sense of fracture inherent in Noguchi’s work.

Noguchi explained that he took “particular satisfaction” in the “fragility” of his interlocking works, which are composed of delicately balanced stone, metal, or wood elements held together only by gravity. 24 He sought in these pieces, which play a starring role in Menken’s film, to imply “imminent motion” and the possibility of “collapse,” and to convey a sense of the “essential impermanence of life.” 25 Despite the interlocking sculptures’ inherent fragility, Menken bounded confidently through the space. She did not shy away from these works, but instead moved quickly and forcefully around their pierced and contorted forms. In the act of circumambulating the work, Menken’s moving body and filmic eye reveal another layer of tantalizing instability in which the contours and shapes of the pieces appear to be in a constant state of change.

LEFT Film sequence of Gregory from Visual Variations on Noguchi.

Isamu Noguchi, Gregory, 1945. Photo: Rudolph Burckhardt. NMA, 12803.

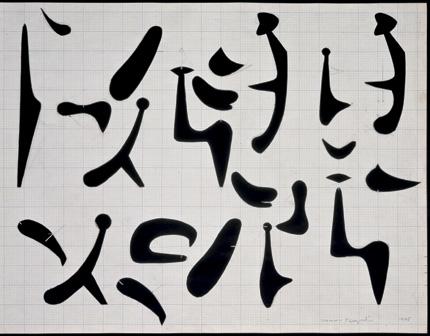

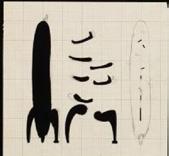

As Menken explores a work like the interlocking sculpture Gregory (1945)— Noguchi’s loose take on a man turned scuttling cockroach, the protagonist in Franz Kafka’s hallucinatory novella The Metamorphosis —she illuminates the sculpture’s violent chasms, transforming the cut-out shapes into a flurry of kinetic form. When constructing his interlocking sculptures, including Gregory, Noguchi developed a process of sketching the abstract components of the works on graph paper. He would then cut out the abstracted shapes and use them as templates to create cardboard models for his slab sculptures, which were quite literally cut up and put back together, and which he would arrange on a miniature stage in his MacDougal Alley studio. He also mounted the leftover sheets of graph paper, with empty space where the components had been cut out, onto black paper, creating new dynamic compositions from the negative space. These bear a notable resemblance to the still frames of Menken’s film. In his worksheet for Gregory, the black spaces of the work’s fragmentary appendages float beside the central body of the sculpture like untethered vertebrae of the spine, and the pierced holes where they insert into the central body are mapped out as black voids. While it is unclear whether Menken would have been aware of this process, her film renders Noguchi’s Gregory as a negative image of his worksheet, so that the holes gleam with white light. As she races across the surface of the work, turning her camera to the side, Noguchi’s uncanny portrait of Gregory becomes even more strange as we lose the moorings of positive and negative space, light and darkness, top and bottom.

The work itself, and Menken’s intriguing treatment of it, reveal the two artists’ shared ambition to express the pervasive sense of disorientation and torment in

the postwar years but also to locate a newfound freedom—and even an ecstatic sense of joy—in fracture. Noguchi would write at this time: “Our existence is precarious, we do not believe in the permanence of things. The whole man has been replaced by the fragmented self . . . [yet] we verge on the impalpable secrets of matter and life, and out of each metamorphosis we see the outlines of a new magnificent reality.”26 Menken similarly explained, “I want to impart hilarity, joyousness, expansion of life with an uncontrollable mirth. I try. Get it? While we have life we are superior to death, but watch out: death might be closer than you know. And that is our end. If I can postpone death even for one minute, I have been successful in my art and so is all art, for art postpones death.” 27

Sharing this sentiment, Dlugoszewski, whose accompanying music amplifies the fragmentation of both Menken’s movements and Noguchi’s sculptures, asserted in an unpublished statement on her music for the film that “although we cherish orderly things . . . and suspect baffling unpredictable unknowable things . . . as imperfects and inferiors, the minute we know, all the sensuous crevices that live for us must stop for it is all finished. The possibility of happening has happened.” She argues that, rather than seek the unified whole, we should “unhappe[n] the world for ourselves.” 28 To achieve this sense of unhappening, Dlugoszewski set out to create music where each sound—even the lighting of a match—feels new and shocking, and achieves a sense of “suchness” because it has been decontextualized, severed from its causal origins, and brought into a delusory aural swirl. It is through this space of fragmentation, fracture, and even chaos, that Noguchi, Menken, and Dlugoszewski invite us to share in their ecstatic sense of freedom.

Isamu Noguchi, Worksheet for Sculpture, c. 1945, including elements for Gregory LEFT Paper maquettes for sculptures in Noguchi’s MacDougal Alley studio, 1940s.

Photo: Andre Kertesz. NMA, 03207.

Isamu Noguchi, Worksheet for Sculpture, c. 1945, including elements for Gregory LEFT Paper maquettes for sculptures in Noguchi’s MacDougal Alley studio, 1940s.

Photo: Andre Kertesz. NMA, 03207.

Menken deftly manipulates light throughout her film to further animate the work on the other side of her camera. Noguchi’s sculptures often appear dramatically lit so that the contours and planes of the works form stark shadows that sometimes interpenetrate and intertwine. Between these flashing lights and dancing shadows, the film is infused with a pulsing visual rhythm.

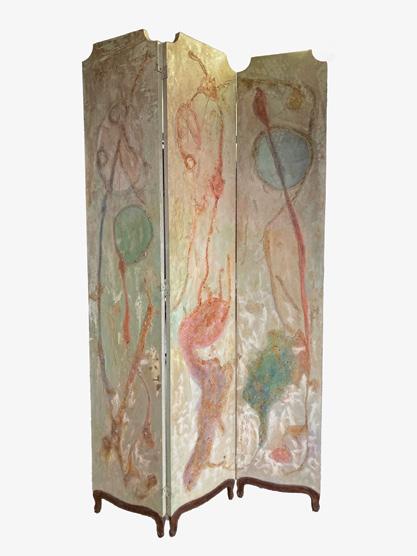

Menken’s interest in the dynamics of moving light was a long-lasting preoccupation, and one that the filmmaker shared with Noguchi. In her painted works— including the unique folding screen on view in the exhibition—Menken often incorporated unconventional materials, including glitter, snakeskin, stone fragments, sand, string, and glass beads, to create highly textured and shimmering surfaces that changed with the viewer’s movement and shifts in light. In 1951, Menken took this to a playful extreme when she installed a series of works created with swirls of phosphorescent “glow-in-the-dark” paint on the walls and ceiling of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York for its inaugural exhibition, titled Pictures for Daytime and Pictures for Nighttime. According to the gallery’s director John Bernard Myers, “With the light on, one image was visible; with the lights turned off, an entirely different image glowed in the darkness.” 29 Although the show received only brief mentions in the press, Myers also recalled that it garnered a certain underground infamy for the “bacchanal” that apparently broke out when the lights went out in the overcrowded gallery. The opening was eventually shut down by the police.30

This interest in light and movement naturally pulled Menken toward film. She explained, “There is no why for my making films. I just liked the twitter of the machine, since it was an extension of painting for me, I tried and loved it. In painting I never liked the staid static, always looked for what would change with source of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads, dyes, even tinted cereals . . . In film-making every frame is a picture and what joy that is! And it

Marie Menken, Lights, 1966. 16mm, color, silent, 6.5 min. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Marie Menken, Lights, 1966. 16mm, color, silent, 6.5 min. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

moves, while the painting is there, stationary for all time.” 31 After Visual Variations on Noguchi, Menken continued her exploration of light in motion, using the movement of her body to construct frenzied and exuberant visions of illuminated subjects, including dancing flames (Hurry! Hurry!, 1957), electrical bulbs (Eye Music in Red Major, 1961), neon signs (Night Writing, 1963), flickering candles (Greek Epiphany, 1963), the glowing moon (Moonplay, 1963), and brightly colored Christmas lights (Lights, 1966).32 Gleaming, refracted, and reflected sunlight and the movement of shadows also recur throughout Menken’s films. These poetic studies of light are both ecstatic and odd, seeming to impart a sense of wonder and awe at the illuminated world, experienced through a moving body. Menken’s close friend and fellow filmmaker Kenneth Anger recalled, “[I]t seemed to me that she was always fascinated with light . . . Her religion was joy . . . Marie would see a little sunlight gleaming off the broken bottle, a little flash of like diamonds and she’d say, ‘how beautiful.’” 33 It’s not hard to imagine that Menken would have also appreciated Noguchi’s claim that “seeing stars from the bottom of a well can also be sculpture.” 34

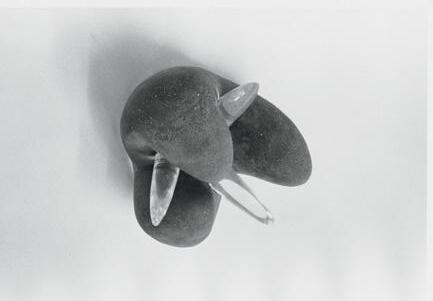

The poetics of light was one of Noguchi’s most famous preoccupations, and he was similarly interested in the dynamic relationship between artificial and natural light. In 1946, the year that Menken likely filmed Visual Variations on Noguchi, Noguchi was engrossed in the production of his electrically illuminated magnesite sculptures, which he called “Lunars,” precursors to the Akari light sculptures he began making in 1951 (the same year Menken hosted her wild glow-in-the-dark gallery exhibition). Noguchi’s motivation for creating the Lunars came from a particularly dark psychological space. While incarcerated in Arizona, Noguchi described the illuminated surface of the moon as offering an imaginary space of escape. He explained, “Not given the actual space of freedom, one makes its equivalent—an illusion within the confines of a room or box—where the imagination may roam to the furthest limits of possibilities, to the moon and beyond.” 35 After his return from Poston into the “artificiality of urban life in New York,” Noguchi continued thinking about the surface of the moon and the dynamics of reflected moonlight, creating a series of lunar landscapes and lights.36 Like the moon, Noguchi’s illuminated sculptures represented a kind of refuge or escape, and they also served as an ambivalent commentary on the state of nature in the wake of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Noguchi saw the sculptures as a response to his dark prediction that “soon, in the atomic age we will all live in caves.” 37 In the face of this new sense of alienation from other humans and nature, Noguchi developed a new appreciation for the dangers of modern technology, but at the same time found light—even artificial light—to have some redemptive potential.

Menken may have first encountered Noguchi’s illuminated works in the lobby of the Time & Life Building, where in 1944 the sculptor installed an unusual ceiling composed of illuminated biomorphic cut-outs. Menken began working for Time Inc. in 1945, first as a typist for Fortune and later working nights at the cable desk of Time Inc.’s Foreign News Section, a position she held for over twenty years to support her artistic career.38 Coming to work she is likely to have passed beneath Noguchi’s gleaming ceiling—an experience that possibly inspired her own light-filled work and filmic portrait of Noguchi. About midway through Visual Variations on Noguchi, Menken turns her attention specifically to the Lunars in Noguchi’s studio, quickly tracing their illuminated surfaces so they light up the screen in a tantalizing flurry. She captures the spirit of one Lunar—a now-lost variation only known to us through photographs—by panning up from the work’s central illuminated form to a rounded plate that hangs above it, catching and reflecting the light. In Menken’s handling of the work, light seems to spin and ripple around this plate, so that it resembles the dappled surface of the moon—Noguchi’s place of escape. Without access to the actual work, it cannot be verified whether this movement was produced from a rotating mechanism within the work, or created with Menken’s moving camera, but the result is a brief and poetic abstraction of light.

In Menken’s film, Noguchi’s Lunar Infant (1944)—a work the sculptor considered his most successful Lunar—appears twice: in a brief instant we see the contours of the illuminated form, and later in the film we see its slowly twisting shadow. More figural than his other Lunars, Lunar Infant reads as an illuminated body dangling between two intersecting frames. Emanating through slits in the magnesite the warm glow of the embedded electrical bulb appears both natural and otherworldly. While its emotional and symbolic ambiguity is part of the work’s strength, the piece could be read as giving form to a new internal light born from the confines or cage of modernity.

Isamu Noguchi’s illuminated ceiling for the Time & Life Building, One Rockefeller Center, New York, c. 1944. NMA, 01644.

Isamu Noguchi’s illuminated ceiling for the Time & Life Building, One Rockefeller Center, New York, c. 1944. NMA, 01644.

In the section of the film focusing on the Lunars, Dlugoszewski’s music also takes a notable turn. Out of the cacophony of sound we hear the curious recitation of names. A man can be heard saying the names Marguerite, Ida, Helena, and Annabel over the abstract vocalizations of two other speakers. Marguerite Ida and Helena Annabel are the names of the unstable and shifting heroine(s) in Gertrude Stein’s play Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights (1938), an absurdist deconstruction of the classic legend of Faust selling his soul for infinite knowledge.39 Written in France in 1938 when Europe was on the brink of World War II, Stein’s modernist retelling casts the title character as a doctor who has traded his soul for electrical light—a comically literal stand-in for “enlightenment.” Because she also developed scores for The Living Theatre’s productions, it is likely that Dlugoszewski, and perhaps many others who were part of the downtown New York art scene, would have seen the first professional production of Stein’s play, which was staged by The Living Theatre in New York in 1951. By alluding to the fragmented figure or figures of Marguerite Ida and Helena Annabel (it is never quite clear if they are one or multiple characters, a device meant to underline the complicated and fractured nature of identity), Dlugoszewski inserts an added layer of complexity, and also a useful interpretative key. She seems to recognize in Menken’s film and Noguchi’s sculpture a counterpoint to the splintered and unstable characters in Stein’s play and the poetic rupture of Stein’s prose. In bringing these works together, Dlugoszewski draws a connection between the three artists reckoning with the metaphoric weight of artificial light—its beauty and horror—in the dawn of the atomic age: the consequences of “lighting the lights.”

Film sequence of Lunar Sculpture Variation.

LEFT I samu Noguchi, Lunar Sculpture Variation, c. 1944 (lost). Photo: Eliot Elisofon. © LIFE Photo Collection / Time Inc.

Film sequence of Lunar Sculpture Variation.

LEFT I samu Noguchi, Lunar Sculpture Variation, c. 1944 (lost). Photo: Eliot Elisofon. © LIFE Photo Collection / Time Inc.

Visual Variations on Noguchi is in a way the result of a fantastic game of telephone: an idea or feeling is refracted, by turns, through the idiosyncratic minds and mediums of Noguchi, Menken, and Dlugoszewski. In a brochure for the film, Menken wrote, “My camera and I took a turn about Noguchi’s studio and the camera-eye recorded the happy journey and when Lucille saw what the camera had seen she too took a happy journey and together it is all happiness.” 40 “All happiness” may at first seem an odd description for this disorienting torrent of moving images and sound, which Stan Brakhage remembered causing “at least one or two people to run screaming from the room—in terror really, at the incredible energy of it” 41 when it was first shown. Although the film has the potential to overwhelm any viewer, and might perhaps be seen as a disruption in the overall quietude of Noguchi’s museum, it also reveals a frenetic and forceful spirit of joy that underlies the fractured disorder of the three artists’ sculptural, filmic, and aural constructions.

In a longer statement about her soundtrack for the film, which is partially quoted in the film’s brochure, Dlugoszewski wrote, “[I]n the face of such glorious bewilderment a sidewalk exists and the me exists and all the infinite number of things exist. But, of course, we are all outside of Eden constantly nibbling the fruit and hearing less and less and just sometimes a miracle of unintelligibility (which we call art) makes a sidewalk exist again . . . bewilderment is glorious because it alone is true.” 42 Out of this glorious bewilderment we may find new sidewalks, or pathways, for navigating the world, embracing fracture, and finding meaning in it. As we navigate the chaotic realities of our own time there is perhaps a lesson to be learned from dancing through space and finding new outlets for ecstatic joy.

1 Parker Tyler, Underground Film: A Critical History (New York: Grove Press, 1969), 158.

2 Gryphon Productions, Visual Variations on Noguchi brochure, c. 1953. Erick Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski Papers, Box 21, Folder 24, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

3 Ibid.

4 P. Adams Sitney, “Interview with Marie Menken,” Filmwise 5–6 (1967): 12.

5 In 1961, Jonas Mekas hosted the first one-woman retrospective of Menken’s work at The Charles Theater in New York, where he screened Visual Variations on Noguchi. He later recounted that Menken provided “direct encouragement and influence” and was making “what he wanted to do” but at the time he did not “dare, fully doing it until [he] saw that she was . . . just doing it.” Martina Kudlácek, dir., Notes on Marie Menken, Icarus Films, 2006.

6 Stan Brakhage, “On Marie Menken,” in Brakhage Scrapbook: Collected Writings 1964–1980, ed. Robert Haller (New York: McPherson, 1982), 91.

7 Stan Brakhage, Film at Wit’s End: Eight Avant-Garde Filmmakers (New York: McPherson & Company, 1989), 38.

8 Leading historian of avant-garde cinema

P. Adams Sitney argued, for instance, that “[t]he rapid pace of the film prohibits contemplation of the sculpture; instead of the slow, reverential camera movements usual in films depicting sculpture, Menken’s rapid sweeps, tilts, and pans affirm her presence and her maneuvering at the expense of Noguchi’s objects so that at times the film seems to represent the open space bounded and shaped by the sculpture rather than the works themselves.” P. Adams Sitney, Eyes Upside Down: Visionary Filmmakers and the Heritage of Emerson (Oxford University Press, 2008), 27.

Although historian Cash (Melissa) Ragona usefully foregrounds Menken’s connection to Fluxus and Pop Art and interest in painterly, plastic, and performance arts, these explorations elide Menken’s specific interests in Noguchi and his work. Melissa Ragona, “Swing and Sway: Marie Menken’s Filmic Events,” in Women’s Experimental Cinema, ed. Robin Blaetz (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 31.

9 Isamu Noguchi, Isamu Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World (New York: Harper & Row, 1968), 39.

10 Sitney, “Interview with Marie Menken,” 11; Lucia Dlugoszewski, “2 notes on the music for Marie Menken’s film on Noguchi,” March 1953, Erick Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski Papers, Box 21, Folder 24, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.; Isamu Noguchi, “Meanings in Modern Sculpture,” Art News 48, no. 1 (March 1949): 14. The Noguchi Museum Archives (NMA), B_CLI_0154_1949.

11 Menken is the subject of Andy Warhol’s Screen Test Marie Menken [ST215] (1966) and his film Bitch (1965). She also acted in Warhol’s films The Life of Juanita Castro (1965), Prison [version 1] (1965), Prison [version 2] (1965), The Gerard Malanga Story (1966), and The Chelsea Girls (1966). Email correspondence with Greg Pierce, Director of Film and Video at The Warhol Museum, June 2023.

12 Marie Menken, Application for Ford Foundation Grant, September 9, 1963. Marie Menken Folder, Anthology Film Archives.

13 Sitney, “Interview with Marie Menken,” 12.

14 The Ballet Society 1: 1946–1947 (New York: Ballet Society, 1947): 55.

15 Willard Maas, “The Gryphon Yaks,” Film Culture 29 (1963): 52.

16 Description attributed to Cinema 16. “Hurry! Hurry!,” The Film-Makers’ Cooperative online catalogue.

17 Sitney, “Interview with Marie Menken,” 11–12.

18 David Vaughn, “Merce Cunningham’s The Seasons,” Dance Chronicle 18, no. 2 (1995): 311. Accepting this story means that the film was shot in 1946, not 1945, Menken’s official date for the film, as 1946 was the year that Kirstein commissioned the dance.

19 Tyler, Underground Film, 158. Filmmaker

Kenneth Anger also remarked on her “feeling for movement and rhythm that was like a dance.” Kudlácek, Notes on Marie Menken

20 Brakhage, Film at Wit’s End, 38; Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 18.

21 Tobi Tobias, Interview with Isamu Noguchi, January 17, 1979, Oral History Project of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library, MGZMT 3-558.

22 Isamu Noguchi, description of Imagined Wing (1944) in Robert Tracy, Spaces of the Mind: Isamu Noguchi’s Dance Designs (New York: Proscenium Publishers, 2000), 34.

23 Gryphon Productions, Visual Variations on Noguchi brochure.

24 Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 28.

25 Ibid., 18, 28.

26 Noguchi, “Meanings in Modern Sculpture,” 14.

27 Sitney, “Interview with Marie Menken,” 11.

28 Dlugoszewski, “2 notes on the music for Marie Menken’s film on Noguchi.”

29 John Bernard Myers, Tracking the Marvelous: A Life in the New York Art World (New York: Random House, 1981), 118.

30 Ibid., 119.

31 Sitney, “Interview with Marie Menken,” 10.

32 Night Writing and early versions of Lights and Moonplay appear in Notebooks (1963)—a compilation representing Menken’s work from the 1940s to the 1960s.

33 Kudlácek, Notes on Marie Menken

34 Thomas B. Hess, “Isamu Noguchi ‘46: An Art News Contemporary Contour,” Art News 45, no. 7 (September 1946): 48. NMA, B_CLI_0487_1946.

35 Isamu Noguchi, “Statement by the artist, 1972,” in Selected Paintings and Sculpture from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, ed. Abram Lerner (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1974), 730.

36 Isamu Noguchi, Kyoto Prize Commemorative Lecture, November 13 1986, 7. NMA, MS_WRI_077_001.

37 Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 27.

38 Although in later accounts Menken noted that she began working at Time Inc. in 1946, internal records indicate that she began working there in May 1945. Internal newsletter, November 4, 1949, Box 366, Folder 23, Time Inc. Bio Files: Marie Menken Maas, MS 3009-RG 2, New-York Historical Society.

39 David Savran, “Whistling in the Dark,” Performing Arts Journal 15, no. 1 (January 1993): 25–27.

40 Gryphon Productions, Visual Variations on Noguchi brochure.

41 Brakhage, Film at Wit’s End, 38. 42 Dlugoszewski, “2 notes on the music for Marie Menken’s film on Noguchi.”

AREA 13

FILM Marie Menken, Visual Variations on Noguchi, 1945/46. Soundtrack 1953. 16mm, black and white, sound, 4 min. Music by Lucia Dlugoszewski. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

AREA 12

AREA 11

Stairs to First Floor

All works collection of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York, unless otherwise noted.

NMA = The Noguchi Museum Archives

Works by Isamu Noguchi © INFGM/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Lee Miller, Isamu Noguchi, New York, 1946. © Lee Miller Archives, England, 2023. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk.

ON PEDESTAL Facsimile of Gryphon Productions, brochure for Visual Variations on Noguchi, c. 1953.

Erick Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski Papers, Box 21, Folder 24, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Isamu Noguchi, Set elements for Martha Graham’s Hérodiade, 1944. Plywood, paint. Gift of the J. M. Kaplan Fund (2002). Backdrop fabricated by Danny Da Silva, 2023.

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity, 1945 (cast 1974). Bronze. Fabricated by TreitelGratz Co.

FILM Marie Menken, Hurry! Hurry!, 1957. Single-channel video (transferred from 16mm film), color, sound, 3 min. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Isamu Noguchi, Five Worksheets for Sculpture, c. 1945–47. Pencil on cut graph paper.

IN TABLE CASE

Archival materials related to The Seasons, 1947. Choreography by Merce Cunningham, music by John Cage, costumes and sets by Isamu Noguchi with contributions by Marie Menken.

NMA, 153746, 153748, 153749, 153750, 153751, 01652, 01653, 01655, 151766, 151769, MS_PROJ_016_001, MS_PUB_036_001

Isamu Noguchi, Study for The Seasons, 1947. Pencil on paper.

TABLE CASE

Facsimile of Dlugoszewski’s “2 notes on the music for Marie Menken’s film on Noguchi,” March 1953.

Erick Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski Papers, Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Isamu Noguchi, Untitled, 1972. Serpentine, marble. Arnold Eagle, Photograph of Martha Graham and May O’Donnell in Graham’s Hérodiade, 1944. NMA, 01577. Isamu Noguchi, E = MC², 1944. Papier-mâché. Isamu Noguchi, The Seed, 1946. Italian marble. IN Photograph of Lucia Dlugoszewski with ladder harp, c. 1960. Photo: Daniel Kramer.Isamu Noguchi, Untitled, 1943 (partially reconstructed 1995). Wood.

Isamu Noguchi, Figure, 1945 (cast 1986). Bronze. Fabricated by Fonderia D’Arte Tesconi, Pietrasanta.

Isamu Noguchi, Gregory, 1945. Slate.

Isamu Noguchi, Mother and Child, 1944–45. Onyx.

Isamu Noguchi, Hanging Man, 1945. Aluminum. Isamu Noguchi, Hanging Man, 1973. Stainless steel.

MURAL Film sequence from Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi depicting Noguchi’s Gregory (1945). Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Isamu Noguchi, Remembrance (Mortality), 1944. American mahogany.

Isamu Noguchi, Avatar, 1947 (cast 1972). Bronze, black patina. Fabricated by Fonderia D’Arte Tesconi, Pietrasanta.

Isamu Noguchi, Two Worksheets for Sculpture (including elements for Gregory at bottom), c. 1945. Pencil on cut graph paper.

Isamu Noguchi, Red Lunar Fist, 1944. Magnesite, plastic, resin, electric components.

Marie Menken, Untitled (Folding Screen), 1956. Paint, seashells, and sand on screen. Anthology Film Archives, Gift of Lorraine Rothbard Gleckman and Family.

FILM Marie Menken, Lights, 1966. Single-channel video (transferred from 16mm film), color, silent, 6.5 min. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

MURAL Film sequence from Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi depicting Noguchi’s lost Lunar Sculpture Variation (c. 1944). Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Isamu Noguchi, Lunar Infant, 1944. Magnesite, wood, electric components.

FILM Marie Menken, Moonplay, 1964. Singlechannel video (transferred from 16mm film), black and white, sound, 5 min. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Isamu Noguchi, Lunar Lamp Prototype, c. 1951. Fiberglass resin, metal, electric components

Isamu Noguchi, Study for Musical Weathervane, 1933. Conté crayon on paper.

Isamu Noguchi, Floating Lunar, 1945. Magnesite, electric components. Gift of Michael and Georgia de Havenon (2021).

of Isamu Noguchi’s sincedestroyed illuminated ceiling for the “Information Center” in the public lobby of the Time & Life Building, One Rockefeller Center, New York, c. 1944. NMA, 01643, 01644.

Stein’s Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights (1938) at The Living Theatre, New York, 1951. Private collection.

Gertrude Stein, Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights (1938), in Gertrude Stein: Writings 1932–1946, ed. Catharine R. Stimpson and Harriet Chessman (New York: The Library of America, 1998).

VIDEO MONTAGE

Excerpts from digitized film reels (c. 1968–70). Multimedia Collection, The Noguchi Museum Archives.

P. Adams Sitney, “Marie Menken and the Somatic Camera,” in Eyes Upside Down: Visionary Filmmakers and the Heritage of Emerson (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Stan Brakhage, “Marie Menken,” in Film at Wit’s End: Eight Avant-Garde Filmmakers (McPherson, 1991).

“On Marie Menken,” in Brakhage Scrapbook: Collected Writings 19641980, ed. Robert A. Haller (Documentext, 1982).

Melissa Ragona, “Swing and Sway: Marie Menken’s Filmic Events,” in Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks, ed. Robin Blaetz (Duke University Press, 2007).

Parker Tyler, “In the Pad: Plastique Versus Surplot,” in Underground Film: A Critical History (Da Capo Press, 1995).

Amy Beal, Terrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia Dlugoszewski (University of California Press, 2022).

“Meanings in Modern Sculpture,” in Isamu Noguchi: Essays and Conversations, ed. Diane Apostolos-Cappadona and Bruce Altshuler (Harry N. Abrams, 1994).

Portrait of Marie Menken.A Glorious Bewilderment: Marie Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi Sep 27, 2023–Feb 4, 2024

The Noguchi Museum, New York

Curated by Kate Wiener

FRONT COVER Film sequence from Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi depicting Isamu Noguchi’s lost Lunar Sculpture Variation (c. 1944). Courtesy Anthology Film Archives. ABOVE Isamu Noguchi, Red Lunar Fist, 1944. Photo: Rudolph Burckhardt. NMA, 12751.

BACK COVER Isamu Noguchi, E=MC², 1944. Photo: Rudolph Burckhardt. NMA, 12733. Quotations from Gryphon Productions brochure for Visual Variations on Noguchi, c. 1953.

© 2023 The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York

Special thanks to Anthology Film Archives; Erick Hawkins Dance Foundation, Inc.; The Film-Makers’ Cooperative; Music Division, Library of Congress; and Mono No Aware.

Exhibitions at The Noguchi Museum are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council and from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.

The Noguchi Museum 9-01 33rd Road Long Island City, NY noguchi.org