11 minute read

The UK Must Forge a New Path of Recovery from COVID-19

THE UK MUST FORGE A NEW PATH OF RECOVERY FROM COVID-19

By Jonathan Marshak

Advertisement

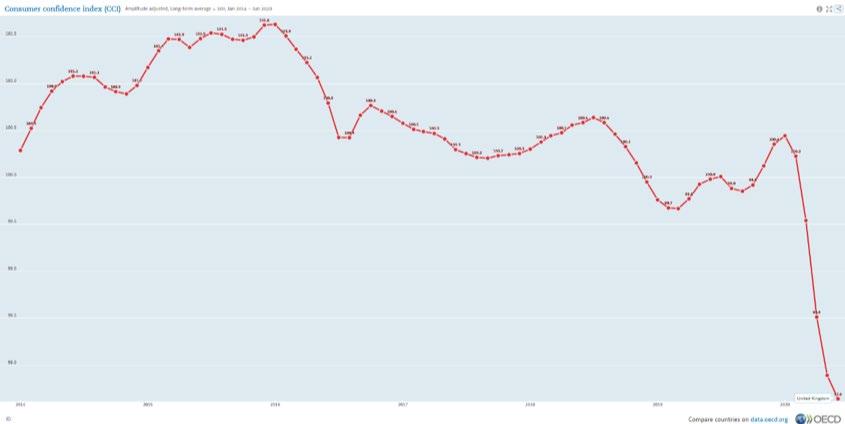

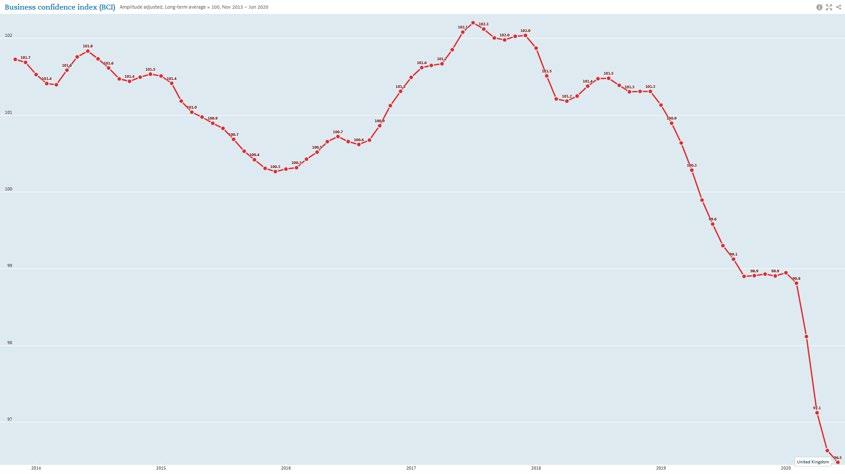

On its current trajectory, the United Kingdom’s economic recovery from the governmentmandated shutdown looks bleak. Not only are we facing a protracted downturn in consumer and business confidence, but the economy must also grapple with being pulled out of the European Union’s single market from 2021. A radical approach in how we finance government expenditure and therefore stimulate the economy must be taken, or we face the prospect of being left behind for good. As the United States contends with civil unrest, the UK must heed its ally’s warning. We cannot let our hidden economic problems continue.

The Chancellor was able to push through policies that would have been thought too radical for the party that brought us austerity only a decade ago. The Treasury has reacted to the crisis so far with £176.7bn of immediate fiscal stimulus, £50bn of tax deferrals and up to £330bn in business loan guarantee programmes, and the highlight being the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme which has effectively nationalised wages for 31 per cent of employees. Not to downplay the scale of this government intervention, but simply propping up businesses until 1st August, at which point businesses will have to pay an increasing share of their employees’ salaries, will only delay the inevitable. The Office for Budget Responsibility warned that up to 20% of the 9.5 million workers placed on furlough could be made redundant. We must avoid what has been seen in the US, where unemployment has doubled compared to levels seen

Figure 1: UK Consumer Confidence Index. Source: OECD

Figure 2: UK Business Confidence Index. Source: OECD

during the 2008-09 financial crisis. However, according to the most recent Deloitte CFO Survey, 61 per cent of CFOs polled wish to reduce costs over the next 12 months, and 90 per cent believe hiring will be scaled back within the same time frame. The combined forces of redundancies, reduced hours and a lack of vacancies, which in particular are 23% lower than at the peak of the financial crisis, has caused real pay to shrink by 1.3% between March and May this year. How much further financial strain can households tolerate, when real wages only surpassed pre-financial crisis levels in February?

In 2018, a study by the Royal Society of Arts found that 70% of the UK’s working population is “chronically broke.” Another worrying feature of our labour market is the rising number of workers in the gig economy and on zero-hour contracts, standing at nearly 6 million people combined. As the workforce face even lower bargaining power due to much reduced job vacancies, it would not be unreasonable to expect these figures to climb further still.

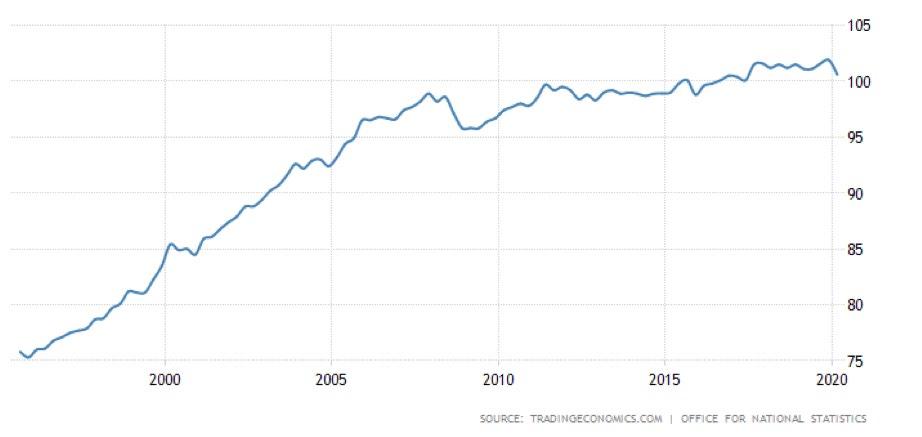

Figure 3: UK Productivity.

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

The UK economy is also experiencing a long-term stagnation in productivity. The cornerstone of long-term growth, the UK has failed to return to the productivity growth levels seen before 2008. As it stands, UK productivity is currently more than 30 per cent behind the US, and around 10-15 per cent behind Germany. There are also stark differences in productivity levels between different geographical regions of the UK. If the Prime Minister is truly concerned with ‘levelling up’, this issue must be tackled first and foremost. Our ‘productivity puzzle’ must be addressed with radical policy reform if we are to avoid being left behind from the next decade and beyond.

In order to relieve the looming financial burden on the middle class, thereby providing a much-needed boost to consumer confidence, the government must go beyond a furlough scheme and provide a Universal Basic Income (UBI) for its population. The long-lasting impact of the financial crisis, and the speed at which the economic fallout from coronavirus took hold, suggests that the current economic stabilisers are inadequate to prevent large downturns in GDP. If we are to sufficiently suppress the troughs of the business cycle (notwithstanding the fully artificial way in which the economy was shut down in March) and address

A UBI would provide remuneration for carers, volunteers and homemakers; work that is undervalued in our society. The scheme, which would replace means-tested benefits, would fulfil one of the government’s main aims; to reduce the bureaucracy and administrational costs in the Department for Work and Pensions. Whilst Universal Credit does try to tackle this problem, it does not go far enough. There is still much stigma associated with applying for benefits, and the process itself may be considered by many an unnecessary one if they think they can get back to work. This is shown by the 500,000 people who have stopped working, not been furloughed and have not claimed benefits during the pandemic. And whilst in principle targeted benefits make a lot of sense, the reality is that the extensive intrusiveness of government get in the way of any savings of efficiency that can be made. In addition, the benefits system in its current form is not one of the ‘untouchable’ arms of government. Election after election, the responsibilities of government departments are changed, the intricacies of policies altered. There is no reason why UBI, a system without all of the needless complexities of Universal Credit, could not reach the status of the National Health Service (NHS), which was one of the few post-war programmes which Thatcher did not want to roll back. This absence of political interference would also help to reduce the economic anxiety felt by many.

An additional advantage of a universal programme is that, in times of crisis, the fiscal stimulus is immediate. The safety in knowing that such an income is accessible could subdue contractions in household expenditure in the event of an economic downturn. Considering that household expenditure accounts for around 60 per cent of the UK’s GDP, mitigating sharp contractions in this area, the likes of which we have seen over the last few months, must be a top priority of government.

The work of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists such as Bill Mitchell and Stephanie Kelton has shown us that we do not need to stick to the rigid fiscal rules of a previous era. If we are to accept that substantial investment is required to recover from this recession, less we experience something akin to the sluggish recovery from the global financial crisis (if we did ever truly recover), then the ideas of such economists must be included in the debate.

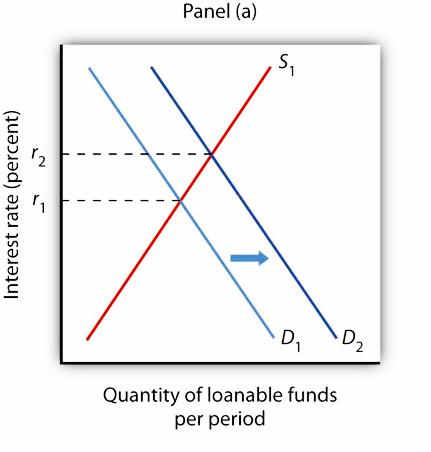

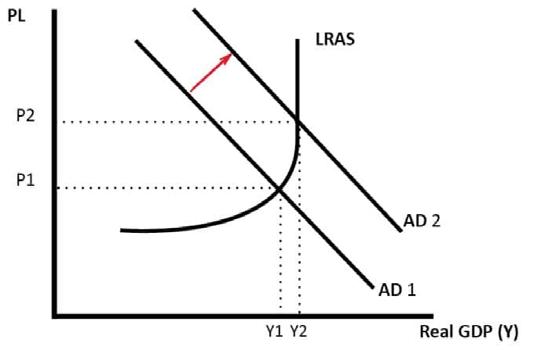

The mainstream, neoclassical view of government spending and deficits says that the government must raise taxes to finance deficits, or risk interest rates climbing higher as both the public and private sector compete over a limited supply of loanable funds. When interest rates are too high, it becomes expensive for private individuals to take out loans and mortgages and for firms to borrow in order to fund investment. This combined effect can cause a drag on economic growth. The government may also have to print money, risking hyperinflation, or default on its debts, tarnishing its reputation and making future borrowing much more expensive.

Figure 4: The Market for Loanable Funds

MMT argues that, providing inflation remains within reasonable bounds, the government can finance its expenditure through deficits and can borrow as much as it likes. This can all take place providing that the government possesses ‘monetary sovereignty’, meaning that the government can control the supply of its own currency. If it needed to, the country could print money to pay off its debts, and can, therefore, never go bankrupt.

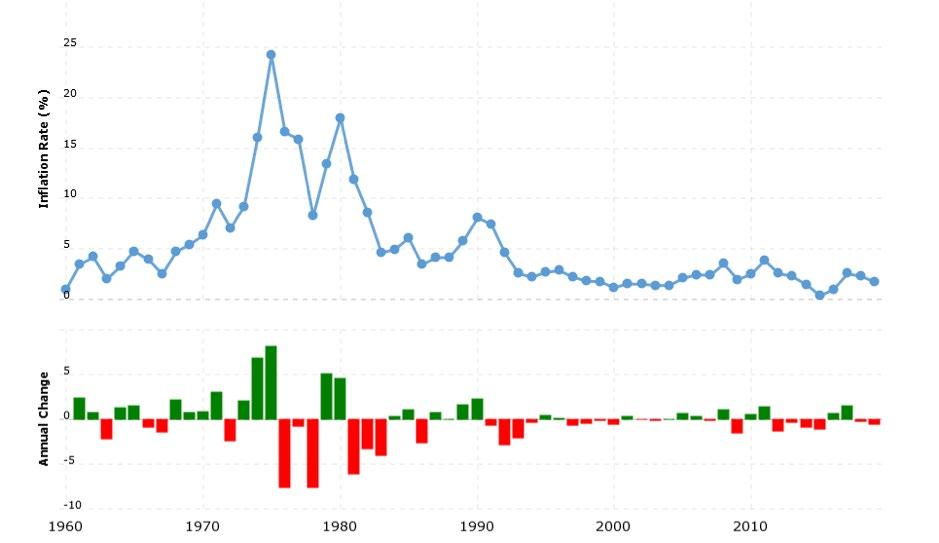

It is important to remember that countries have been printing trillions of dollars since the financial crisis. In the UK, the government initiated a Quantitative Easing (QE) programme totalling £745 billion as of June 2020. However, we have yet to see inflation reaching anywhere near the ‘crisis levels’ of the 1970s.

In the US, the Federal Reserve’s asset purchasing programme peaked at $4.5 trillion in 2015, before climbing to over $7.1 trillion in April 2020, a figure which could reach $10 trillion by the end of the year. In addition, The European Central Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme has been extended to €1.35 trillion, and could potentially rise by a further trillion euros. The sheer scale of these programmes, which are in effect money-printing efforts, has furthered the case for MMT. We have not seen rising inflation in the economic regions that have used QE programmes. MMT economists argue that it is the lack of productive capacity in an economy, rather than the printing of money itself, which will lead to inflation.

On the subject of deficits, MMT economists such as the late Wynne Godley say that if the government is running a deficit, then there must be a surplus elsewhere in the economy. If anything, it is important that the government should continue to run a deficit, as to run a fiscal surplus means that there is a private sector deficit. This would only be necessary in instances where there is high inflation, but if there is not, then the leading MMT economists Mitchell, Wray and Watts say that recessions will occur, such as in 2001.

Mitchell, Wray and Watts have more to say on the framework of how government financing and expenditure works. They say that the government taxes for two reasons. Firstly, so that residents must use the sovereign currency for tax payments, meaning that it will also be used for consumption. This gives the government control over its currency. Upstart currencies such as Bitcoin and Libra threaten the effective monopoly that governments have in this area. Taxes are also used as a contractionary fiscal policy in order to reduce inflation. By lowering the amount of money that consumers and businesses have to spend, the government can prevent aggregate demand passing the threshold of full employment, which would lead to a dangerous rise in inflation. For this purpose, MMT economists argue that taxes are still necessary.

Figure 5: Keynesian View of LRAS

Source: www. macrotrends.net

The upshot of MMT is the realisation that governments, within the limits of inflation, have room to increase public expenditure without the need to raise taxes. Depending on the level of inflationary pressure, there may even be room to reduce taxation as a way of boosting economic growth. This new strand of economic thinking will become increasingly more mainstream as governments look for ways to address the recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

As the public become increasingly aware of environmental issues, we should expect to see politicians and businesses react to the preferences of their respective voters and consumers. Businesses have called for the prioritisation of a ‘green economic recovery’ in the UK, and it is now up to the government to carry out its response. Boris Johnson has said that it would be a ‘mistake’ to return to austerity, which will mean greater public borrowing from a government much less worried about the links between debt and economic growth than it was just a decade ago.

If the government is serious about fixing the UK’s productivity crisis, which has to be a top priority if we are to avoid another stagnant recovery, then it must find the fiscal manoeuvrability to enact major economic reforms such as UBI. The Chancellor has shown willingness to go beyond the norm through his furlough scheme. He must continue this momentum in order to aid our recovery and ensure our collective prosperity in the years ahead.

References

“Consumer confidence index (CCI)”, OECD, 2020. Accessed: July 22nd 2020. https://data.oecd.org/leadind/consumer-confidence-index-cci.htm; “Business confidence index (BCI)”, OECD, accessed July 22nd 2020, https://data.oecd.org/ leadind/business-confidence-index-bci.htm#indicator-chart.

“Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme statistics: July 2020”, HMRC, 2020. Accessed: July 22nd 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirusjob-retention-scheme-statistics-july-2020/coronavirus-job-retention-schemestatistics-july-2020.

Partington, Richard. “UK paid employment falls by almost 650,000 as Covid-19 crisis bites.” The Guardian, July 16th 2020. Accessed: July 23rd 2020. https://www. theguardian.com/business/2020/jul/16/number-of-uk-workers-on-companypayroll-falls-by-650000-amid-covid-19-crisis

Lacurci, Greg. “A second Great Depression? Unemployment crisis hits big cities hard.” CNBC, July 21st 2020. Accessed: July 22nd 2020. https://www.cnbc. com/2020/07/21/some-big-cities-are-hitting-great-depression-unemploymentlevels.html

“Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: July 2020”, ONS, 2020. Accessed: July 23rd 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/ employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/averageweeklyearningsingreatbritain/ july2020

"Labour market economic commentary: February 2020”, ONS, 2020. Accessed: July 23rd 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/ peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/ labourmarketeconomiccommentary/february2020

Robertson, Harry. “Tackling UK productivity crisis could yield £83bn a year for economy, says PwC.” City A.M, November 26th 2019. Accessed: July 23rd 2020. https://www.cityam.com/tackling-uk-productivity-crisis-could-yield-83bn-a-yearfor-economy-says-pwc/

Inman, Phillip. “UK’s hidden problem of rising unemployment may soon be exposed.” The Guardian, July 16th 2020. Accessed: July 23rd 2020. https:// www.theguardian.com/business/2020/jul/16/rising-unemployment-uk-hiddenproblem-furlough-coronavirus

“Consumer trends, UK: April to June 2019”, ONS, 2019. Accessed July 23rd 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/satelliteaccounts/bulletins/ consumertrends/apriltojune2019

“What is quantitative easing?”, Bank of England, 2020. Accessed: July 24th 2020. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/quantitative-easing

“Credit and Liquidity Programs and the Balance Sheet”, Federal Reserve, 2020. Accessed: July 24th 2020. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/ bst_recenttrends.htm

Smith, Elliot. “ECB could boost bond buying by another trillion euros, economist projects”. CNBC, June 29th 2020. Accessed: July 24th 2020. https://www.cnbc. com/2020/06/29/ecb-could-boost-bond-buying-by-another-trillion-euroseconomist-projects.html

Matthews, Dylan. “Modern Monetary Theory, explained”. Vox, April 16th 2019. Accessed: July 26th 2020. https://www.vox.com/futureperfect/2019/4/16/18251646/modern-monetary-theory-new-moment-explained

“UK ‘must prioritise green economic recovery’”, BBC News, May 8th 2020. Accessed: July 26th 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-52580291