16 minute read

Returning to Pride's Intersectional Roots

Alex Jacobs / International Affairs and History 2022

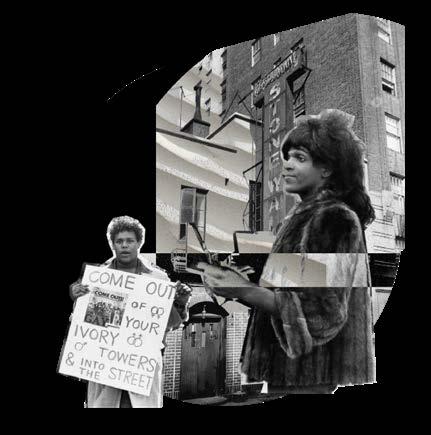

The 1969 Stonewall Riots, one of the major kickoff points for the gay liberation and modern LGBTQ+ rights movements, was a multi-night rebellion against the police.[1][2][3]

Black trans women of color, namely Marsha P. Johnson and Miss Major GriffinGracy, were central figures at Stonewall and in the movement it sparked.[4][5] The Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day March in 1970, which commemorated the first anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, inspired similar marches around the US, eventually leading to our present-day Pride parades.[6]

The original protests were led by some of the most marginalized community members, including people of color, trans women, homeless people, and sex workers. But today it is increasingly corporatized.[7][8] This commercialization has created problems—such as organizers’ involvement with military contractors, a focus on brands rather than community organizations, and expensive parade fees—that marginalize vulnerable community members. [9] Increased police presence also makes some people of color feel less safe at Pride parades.[10] Mainstream Pride events do not reflect the intersectionality of the community, its history, or its members. However, in the unique circumstances of 2020, Black LGBTQ+ people made sure their voices were heard and began to shift Pride back toward intersectionality.

Lawyer, civil rights advocate, and professor Kimberlé Crenshaw describes intersectionality as the “interactive effects of discrimination.”[11][12] People at an intersection of marginalized identities—race, gender, class, sexuality—are affected differently by politics and systemic oppression, often excluded from discrimination discussions that focus on “otherwise-privileged” members of any particular identity.[13][14] In the LGBTQ+ community, an awareness of intersectionality means that we do not think everyone’s experiences are the same as those of White, wealthy, able-bodied, cisgender, gay men.

Awareness of intersectionality helps us to acknowledge, understand, and ground our differences in identity and experiences. [15] Thus, we can make space for these differences in our construction of group politics

and make sure that we meet the different needs of diverse groups within our community.[16] Mainstream Pride has failed to

do so.[17][18]

Pride’s lack of intersectionality is not new. Since 1988, there has been an annual Los Angeles Black Pride due to widespread racism in Pride organizations and the gay community, including racist admission policies at a popular gay nightclub, negative comments about Black men’s clothing, and the reluctance of gay bars and clubs to hire Black men.[19][20][21][22]

“It was clear Pride was never for us,” noted Jeffrey King, a sixty-one-year-old Black organizer and founder of the In the Meantime Men’s Group.[23] When discussing his past Pride experiences, he noted getting drinks poured on him, being inapficulty entering events and venues. [24] Miss Major has long discussed the broader LGBTQ+ movement’s exclusion of people like her, along with the need for those directly affected to lead their own movements.[25][26]

Racism within major Pride organizations and the vastly different experiences of Black LGBTQ+ people were even more apparent this year.[27] On June 14, organizers in Los Angeles held an All Black Lives Matter march, aiming to amplify Black queer voices and unite in solidarity while also supporting Black Lives Matter (BLM) demands regarding policing reform.[28]

While the All Black Lives Matter march drew at least thirty thousand people, the march’s origins demonstrate the ignorance of White-led LGBTQ+ organizations regarding Black queer experiences.[29] Christopher Street West (CSW), the organization which produces the annual LA Pride parade and festival, has been frequently criticized for being too White and corporate.[30] At the beginning of June, CSW announced the All Black Lives Matter march as a solidarity march with BLM. But Black Lives Matter Los Angeles never endorsed the event and CSW did not reach out to any other Black LGBTQ+ organizers.[31][32]

CSW’s special event permit application to the Los Angeles Police Department further demonstrates a lack of awareness. Amid protests against police racism and brutality—including in the LAPD—CSW’s application cited “strong and unified partnership with law enforcement” and that LAPD’s “support of this peaceful gathering is key to its success.”[33][34] In the end, a fairly new group, Black LGBTQ+ Activists for Change, took over organizing the march while CSW apologized and withdrew.[35] CSW’s actions

demonstrate how far from intersectional many Pride organizations are and how much work is needed to make Pride a meaningful experience for the entire community.

These issues are widespread in Pride organizations around the country. According to former committee chair Casey Dooley, when drafting an initial statement regarding the anti-racism protests, Boston Pride did not even consult its own Black and Latinx Pride committee.[36] In response to Boston Pride’s lack of Trans Resistance Vigil and March on June 13.

While Boston Pride apologized and released a revised statement, this is a much larger, systemic issue that cannot be solved that easily.[37]

Reverend Irene Monroe, an African American lesbian activist who was at Stonewall in 1969, noted, “Because of the tension that has gone on in Boston for fifty years . . . groups like Black Pride and Latinx Pride . . . come about [because] the larger Pride organizational committee did not consider those voices. We weren’t at the table.”[38]

Boston Pride 4 The People is a new organization composed of former volunteer members of Boston Pride, including Dooley, who resigned due to Boston Pride’s response to the protests.[39] The new organization’s June 30 statement called for the resignation of Boston Pride’s entire board.

Despite such long-term, systemic issues in Pride organizations around the country, this year seemed to be a turning point. Pride started to look different as soon as major cities began canceling parades due to COVID-19. San Francisco Pride canceled its parade on April 14, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio canceled NYC Pride on April 20, and CSW canceled LA Pride on May 7.[40][41][42] By the end of April, organizers had canceled or postponed about 280

propriately touched, and having dif-

Pride events globally.[43] However, the country experienced a

seismic shift after the murder of George Floyd by Minnesota police on May 25 and the start of nationwide BLM protests.[44] Pride also shifted in tone. At the LA All Black Lives Matter march, Black lesbian protester Eyvonne Leach discussed the role of the pandemic in attracting national attention to Floyd's

explicit support for BLM, committee member The country could no longer ignore racism and the harm it has caused.[46] People began paying more atten“ Athena Vaughn organized a Black-activist-led tion to the importance of intersectionality

murder by forcing us to “put [our] lives on pause.”[45] in the Pride and BLM movements after the May and June killings of Black trans man Tony McDade and Black trans women Nina Pop, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, and Riah Milton.[47][48]

Though trans women of color have been integral to the LGBTQ+ rights and BLM movements from the start, they have never shared fully in the gains of either one.[49] Transgender women of color, particularly Black trans women, are disproportionately killed.[50] But during an intersection of LGBTQ+ activism and BLM in a time of extraordinary circumstances, Black LGBTQ+ people made sure their voices were—and will continue to be—heard.[51]

In addition to the LA All Black Lives Matter March, the June 14 Brooklyn Liberation March drew fifteen thousand people to the area surrounding the Brooklyn Museum.[52] It was a rally and silent march meant to evoke the NAACP’s 1917 Silent Parade, at which ten thousand people wearing white demanded an end to

violence against Black people.[53] The overarching mission of Brooklyn Liberation was to bring Black transgender and gender-nonconforming people into the global conversation about Black lives.[54]

In one of the few concrete wins this year, the Supreme Court ruled in June that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects LGBTQ+ people from workplace discrimination.[55] However, in her speech at Brooklyn Liberation, Black trans activist Raquel Willis pointed out a glaring disparity, one that explicitly demonstrates the need to examine, critique, and improve Pride through an intersectional lens.[56]

“Yes, the legislation matters,” she said. “But White queer folk get to worry about legislation while Black queer folk [worry] about our lives.”[57]

Organizers held smaller marches focusing similarly on Black LGBTQ+ people and their experiences. Thousands joined Athena Vaughn’s Boston Trans Resistance Vigil and March on June LGBTQ+ community and BLM marched toward the White House and the mayor’s house.[59] Marches in Denver and Chicago also drew hundreds and thousands of people, respectively, on June 14.[60][61]

This year, as Athena Vaughn discussed, Black trans people decided to “fight for [themselves] and to remind people what Pride was all about,” returning to the idea of Pride as a “resilience and a resistance.”[62] In New York City, the Reclaim Pride Coalition is doing similar work. It hosted its first Queer Liberation March in June 2019 to contrast with New York’s commercial World Pride.[63][64] Last year, the march aimed to honor the history and legacy of queer liberation struggles, resist oppression, and celebrate the gains made through queer resistance.[65]

This year’s march was originally canceled due to COVID-19, but protests against police brutality reminded the organizers why the Queer Liberation March formed and why fighting for justice is necessary even during a pandemic.[66] Thus, Reclaim Pride organized a march on June 28, renaming it the “Queer Liberation March for Black Lives and Against Police Brutality” and committing to focus on marginalized voices. It drew thousands of demonstrators, in great contrast to the more symbolic gesture of NYC Pride’s procession that same day.[67] brown trans people,” said Francesca Barjon, one of the march’s organizers.[68] “We need to listen to Black people, Black trans people, and Black LGBTQ people who have been speaking up for decades and haven’t been listened to.”

Due to this decades-long lack of attention, some LGBTQ+ people of color, people who have worked for years to address the intersection of racial and gender injustice, thought others would never care.[69] But protesters made this year’s Pride different.

“If you have an organization that has no Black trans leadership, if you have an organization that has no specific Black trans programming or funding, you are obsolete,” Willis remarked at Brooklyn Liberation.[70]

The larger Pride organizations like CSW,

Boston Pride, and NYC Pride have a long way

to go and many changes to make. The work

and efforts of LGBTQ+ people this year demonstrated that Pride can and must be better.

Though the prospect of Pride parades in the post-pandemic world is exciting, the LGBTQ+

13.[58] In Washington, DC, members of the

community must continue what its Black members emphasized this year: awareness of intersectionality and

centering the voices of the most marginalized. And we must pressure large Pride organizations to be more aware of the diverse identities and experiences within our community, while they have never shared fully the Reclaim Pride Coalition that work in the gains of either one. to make Pride better. This year, people are finally “We did this march to center Black and listening and the fight is picking up steam.[71] Pride brought a long-overdue focus on intersectionality and listening to Black LGBTQ+ people. But to ensure Pride “

supporting smaller organizations like becomes intersectional and meaningful for everyone, this kind of organizing must continue in the long-term—we simply cannot go back to “normal” Pride when the pandemic is over.

[1] Solomon, Andrew. “The First New York Pride March Was an Act of 'Desperate Courage'.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 27, 2019. [2] Barron, James. “Pride Parade: 50 Years After Stonewall, a Joyous and Resolute Celebration.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 30, 2019. [3] Solomon, Andrew. “The First New York Pride March Was an Act of 'Desperate Courage'.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 27, 2019. [4] Chan, Sewell. “Marsha P. Johnson, a Transgender Pioneer and Activist.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 2018. [5] Stern, Jessica. “This Is What Pride Looks Like: Miss Major and the Violence, Poverty, and Incarceration of Low-Income Transgender Women.” S&F Online. Barnard Center for Research on Women, n.d. [6] Zaveri, Mihir, and Michael Gold. “How the Virus and Protests Changed a 50-Year Celebration of Pride.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 28, 2020. [7] Evans, Dain. “Pride 2020: How LGBTQ Pride Month Went from Movement to Marketing.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, June 9, 2020. [8] Thompson, Hunter C. Queer’Ing Corporate Pride: Memory, Intersectionality, And Corporeality In Activist Assemblies Of Resistance. Thesis, Syracuse University, 2018. [9] Queer’Ing Corporate Pride: Memory, Intersectionality, And Corporeality In Activist Assemblies Of Resistance. [10] Zaveri, Mihir, and Michael Gold. “How the Virus and Protests Changed a 50-Year Celebration of Pride.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 28, 2020. [11] “Kimberlé Crenshaw.” TED. TED Conferences, n.d. [12] Marshall, Grace Berit. “Can We Be Proud Of Pride? A Discussion on Intersectionality in Current Canadian Pride Events.” Canadian Journal of Undergraduate Research 2, no. 2 (2017). [13] The Michigan Daily Editorial Board. “From The Daily: Understanding Intersectional Pride.” The Michigan Daily. University of Michigan, July 1, 2020. [14] Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum, no. 1 (1989): 139–67. [15] Crenshaw, Kimberle Williams. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Essay. In The Public Nature of Private Violence, edited by Martha Albertson Fineman and Rixanne Mykitiuk, 1st ed., 93–118. New York: Routledge, 1994. [16] “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” [17] Marshall, Grace Berit. “Can We Be Proud Of Pride? A Discussion on Intersectionality in Current Canadian Pride Events.” Canadian Journal of Undergraduate Research 2, no. 2 (2017). [18] Stern, Jessica. “This Is What Pride Looks Like: Miss Major and the Violence, Poverty, and Incarceration of Low-Income Transgender Women.” S&F Online. Barnard Center for Research on Women, n.d. [19] Branson-Potts, Hailey, and Matt Stiles. “All Black Lives Matter March Calls for LGBTQ Rights and Racial Justice.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2020. [20] Scott, Henry E. “Black LGBTQ Leaders Call Out LA Pride and WeHo for History of Discrimination.” WEHOville. WHMC, June 10, 2020. [21] Kilhefner, Don. “Jim Crow Visits West Hollywood: Studio One and Gay Liberation.” WEHOville. WHMC, August 5, 2016. [22] Scott, Henry E. “Black LGBTQ Leaders Call Out LA Pride and WeHo for History of Discrimination.” WEHOville. WHMC, June 10, 2020. [23] Branson-Potts, Hailey, and Matt Stiles. “All Black Lives Matter March Calls for LGBTQ Rights and Racial Justice.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2020. [24] “All Black Lives Matter March Calls for LGBTQ Rights and Racial Justice.” [25] Stern, Jessica. “This Is What Pride Looks Like: Miss Major and the Violence, Poverty, and Incarceration of Low-Income Transgender Women.” S&F Online. Barnard Center for Research on Women, n.d. [26] Grullón Paz, Isabella, and Maggie Astor. “Black Trans Women Seek More Space in the Movement They Helped Start.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 28, 2020. [27] Stern, Jessica. “This Is What Pride Looks Like: Miss Major and the Violence, Poverty, and Incarceration of Low-Income Transgender Women.” S&F Online. Barnard Center for Research on Women, n.d. [28] Gomez, Elena. “Thousands Gather in Hollywood for All Black Lives Matter Solidarity March Led by Black LGBTQ+ Community.” ABC7 Los Angeles. KABC-TV, June 15, 2020. [29] City News Service. “Tens of Thousands March in Hollywood and West Hollywood for All Black Lives Matter Protest.” NBC Los Angeles. NBC Southern California, June 15, 2020. [30] Branson-Potts, Hailey, and Matt Stiles. “All Black Lives Matter March Calls for LGBTQ Rights and Racial Justice.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2020. [31] “All Black Lives Matter March Calls for LGBTQ Rights and Racial Justice.” [32] City News Service. “Tens of Thousands March in Hollywood and West Hollywood for All Black Lives Matter Protest.” NBC Los Angeles. NBC Southern California, June 15, 2020. [33] Bates, Karen Grigsby. “'It's Not Your Grandfather's LAPD' - And That's A Good Thing.” NPR. NPR, April 26, 2017. [34] Tirado, Fran. Twitter, June 5, 2020. [35] LA Pride (@lapride). 2020. Instagram photo, June 9, 2020. [36] Kearnan, Scott. “Boston Pride's Response to the Black Lives Matter Protests Is a Shame.” Boston Magazine. Boston Magazine, June 12, 2020. [37] “#BlackLivesMatter.” Boston Pride. Boston Pride Committee, June 4, 2020. [38] Kearnan, Scott. “Boston Pride's Response to the Black Lives Matter Protests Is a Shame.” Boston Magazine. Boston Magazine, June 12, 2020. [39] Gray, Arielle. “LGBTQ+ Activists Clash With Boston Pride, Demand Board Resignation.” The ARTery. WBUR, July 1, 2020. [40] “San Francisco Pride Announces Cancellation of 2020 Parade And Celebration.” San Francisco Pride. San Francisco Pride Celebration Committee, April 14, 2020. [41] Fitzsimons, Tim. “NYC LGBTQ Pride March Canceled for First Time in Half-Century.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, April 21, 2020. [42] Vega, Priscella. “Coronavirus Torpedoes 50th L.A. Pride Parade; Online Celebration Planned.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, May 7, 2020. [43] Burns, Katelyn. “What Will Pride Mean This Year?” Vox. Vox, April 29, 2020. [44] Hill, Evan, Ainara Tiefenthäler, Christiaan Triebert, Drew Jordan, Haley Willis, and Robin Stein. “How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody.” The New York Times. The New York Times, May 31, 2020. [45] Branson-Potts, Hailey, and Matt Stiles. “All Black Lives Matter March Calls for LGBTQ Rights and Racial Justice.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2020. [46] Chughtai, Alia. “Know Their Names: Black People Killed by the Police in the US.” Al Jazeera Interactives. Al Jazeera, 2020. [47] Allen, Joshua. “Why Organizers Are Fighting to Center Black Trans Lives Right Now.” Vox. Vox, June 18, 2020. [48] Carlisle, Madeleine. “Two Black Trans Women Were Killed in the Past Week.” Time. Time, June 13, 2020. [49] Grullón Paz, Isabella, and Maggie Astor. “Black Trans Women Seek More Space in the Movement They Helped Start.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 28, 2020. [50] “Violence Against the Transgender Community in 2020.” HRC. The Human Rights Campaign, 2020. [51] Grullón Paz, Isabella, and Maggie Astor. “Black Trans Women Seek More Space in the Movement They Helped Start.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 28, 2020. [52] Willis, Raquel (@raquel_willis). 2020. Instagram photo, June 15, 2020. [53] Allen, Joshua. “Why Organizers Are Fighting to Center Black Trans Lives Right Now.” Vox. Vox, June 18, 2020. [54] “Why Organizers Are Fighting to Center Black Trans Lives Right Now.” [55] Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. (2019). [56] Willis, Raquel (@raquel_willis). 2020. Instagram video, June 17, 2020. [57] Willis, Raquel (@raquel_willis). 2020. Instagram video, June 17, 2020. [58] Walters, Quincy. “Thousands March In Boston For Black Transgender Lives.” WBUR News. WBUR, June 14, 2020. [59] Heim, Joe, Rachel Chason, Laura Vozzella, and Hannah Natanson. “D.C. Protesters Dance Outside Mayor's Home, Demanding She Defund Police.” The Washington Post. WP Company, June 14, 2020. [60] Allen, Taylor. “Pride Meets Black Lives Matter In Sunday March In Denver And Draws Hundreds.” Colorado Public Radio. Colorado Public Radio, June 14, 2020. [61] Pope, Ben. “Drag March For Change Protests against Racial Injustice in America, Chicago, Boystown.” Times. Chicago Sun-Times, June 14, 2020. [62] “This Pride Month, The Focus Was On Black Lives Matter.” Radio Boston. WBUR, June 30, 2020. [63] “History Statement.” Reclaim Pride Coalition, n.d. [64] Kilgannon, Corey. “'Clash of Values': Why a Boycott Is Brewing Over Pride Celebrations.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 20, 2019. [65] “History Statement.” Reclaim Pride Coalition, n.d. [66] Lang, Nico. “Queer Pride Is Going Back to Its Protest Roots.” Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone, June 9, 2020. [67] Zaveri, Mihir, and Michael Gold. “How the Virus and Protests Changed a 50-Year Celebration of Pride.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 28, 2020. [68] Lang, Nico. “Queer Pride Is Going Back to Its Protest Roots.” Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone, June 9, 2020. [69] Allen, Joshua. “Why Organizers Are Fighting to Center Black Trans Lives Right Now.” Vox. Vox, June 18, 2020. [70] Willis, Raquel (@raquel_willis). 2020. Instagram video, June 17, 2020. [71] Allen, Joshua. “Why Organizers Are Fighting to Center Black Trans Lives Right Now.” Vox. Vox, June 18, 2020.