9 minute read

Ruapehu Recurring Andy Hoyle

Recurring

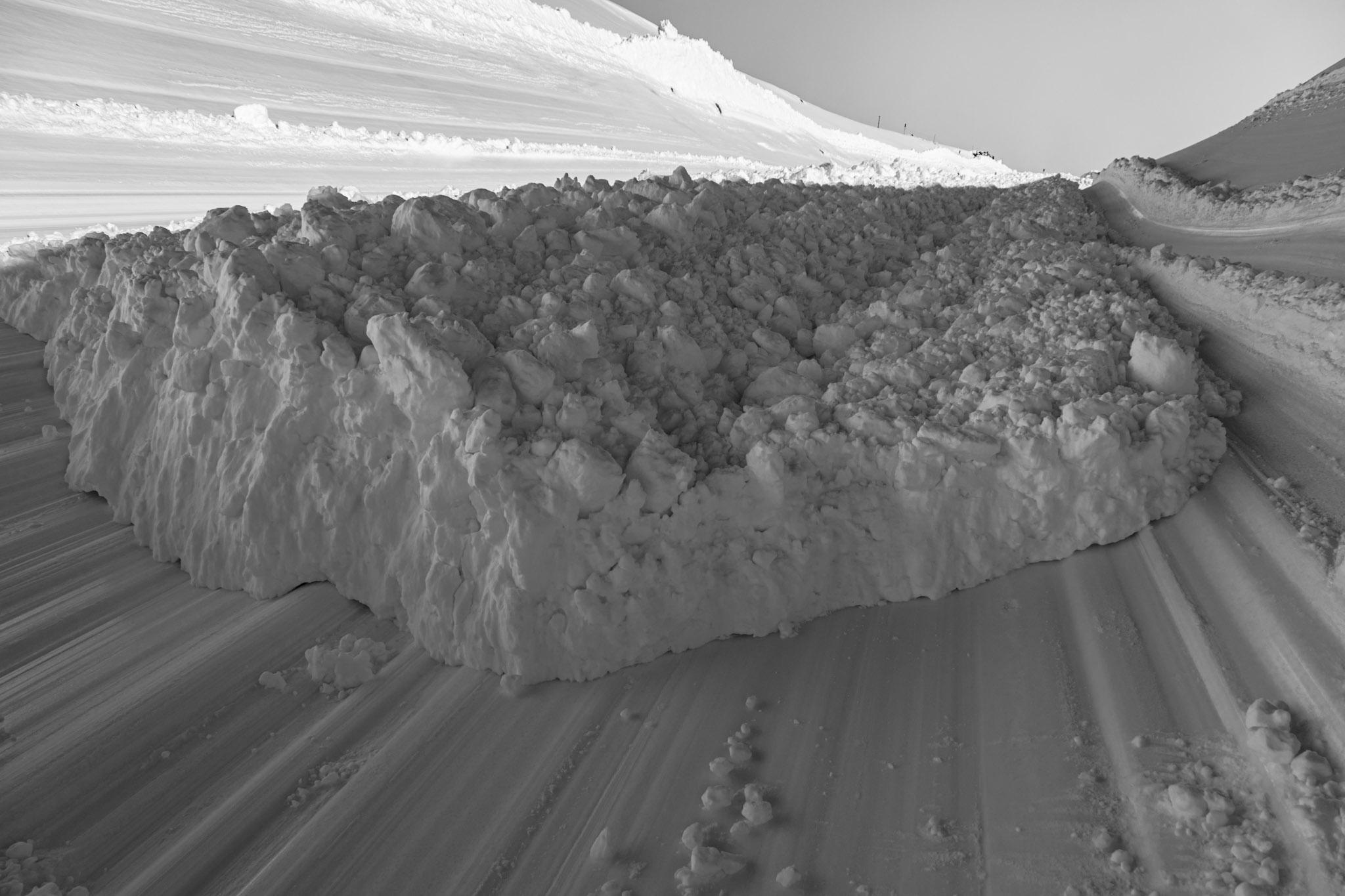

Upper Big Bowl Size 4 event, lower track. At this elevation it is clear it was in a slow flowing mode and sticking primarily to drainages. The crown walls are visible in the background in shade just below ridge top. Ruapehu 2

Advertisement

The 201 9 Ruapehu Avalanche Cycle

By Andy Hoyle

All images Andy Hoyle unless otherwise noted.

Over the course of the previous two winter seasons what we know about avalanche control at Turoa has changed dramatically. Over the last 300,000 winters (or more depending on your belief system) since Ruapehu was formed, it's a certainty that ‘Koro’ has seen it all before. Our meager 100 years of ‘records’ gave us a very false sense of confidence in our ability to predict run out distances for the high altitude avalanche paths on Ruapehu. Of course there were the locals around the place that took pleasure in telling us how often they have seen these sort of events and how it was ‘nothing to write home about’. Well, we’re writing about it because it is an interesting story and we think it’s these sorts of interesting stories that make awesome learning experiences for all others who might be in similar positions in the future - here on Ruapehu or elsewhere. During the second half of July 201 9, both ski area snow safety teams (Turoa and Whakapapa) were tracking several interesting layers of concern on various aspects and it was pretty clear that once there was more load placed on these weak layers of facets we might be in for some significant results. It just so happened we were about to descend into a solid week long storm session where we would log around 1 1 2 cm of new snow.

‘We had 2 noted facet layers that formed early in the season: 190706, and approximately 190720). The first was pretty quickly buried and heavily tested with no results and was considered dead. The second was destroyed by a rain event and subsequently put to bed.’ Ryan Leong - Whakapapa Snow Safety Officer.

In July 201 9 we had around 1 40cm on the stakes at 2000m. On various aspects around the mountain we had what could be described as a slightly unusual situation brewing for the North Island: some form of faceted grain type causing deep and (somewhat) persistent weak layer(s). Most of the time on Mt Ruapehu we deal with storm snow weaknesses which can be resolved in 24-48 hours, either through passive or active control measures. However, just to keep us on our toes, every now and then, we are thrown a more challenging puzzle to work through.

On August 6, the Whakapapa team managed a size 3.5 out of Te Heu Heu Valley Headwall - True Left.

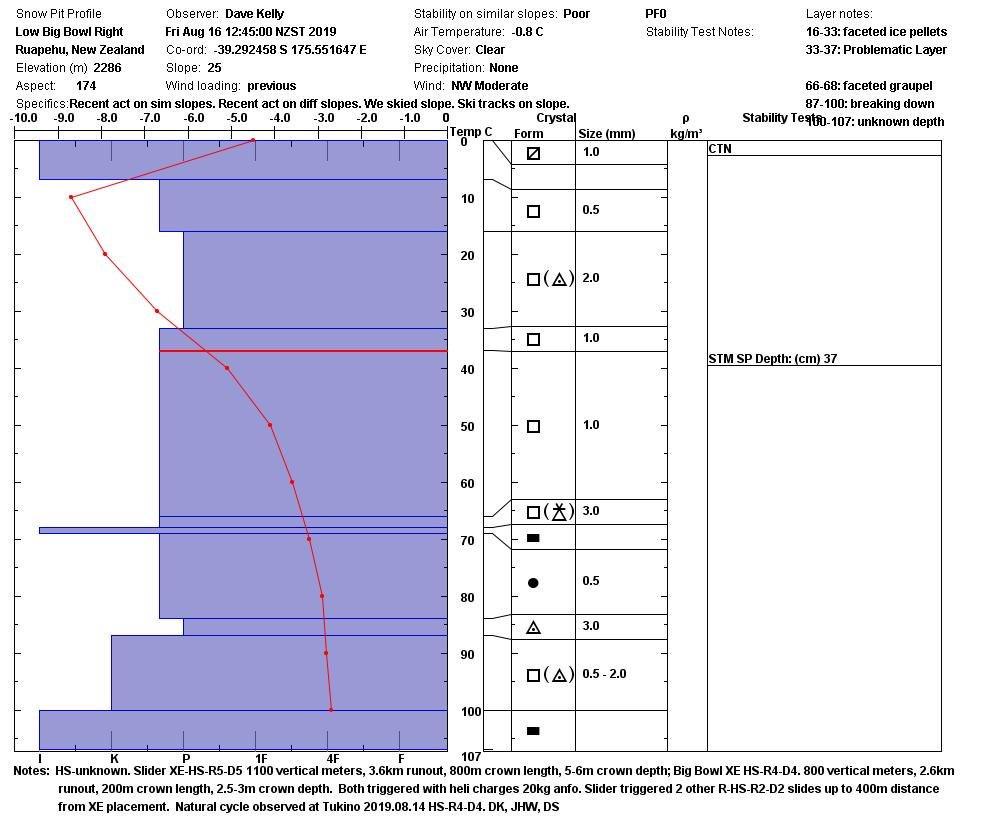

Photo 3: Snow profile performed by Turoa Snow Safety Officer Dave Kelly on the 16th of August - a day after the large results at Turoa. The events ofthis cycle appear to have occurred on the problematic layer identified at around 37cm on this profile in faceted grains. Crown depths for Upper Slider around 5-6m in the start zone!

Photo 4: Control team above the Te Heu Heu Valley Headwall - True Left start zone with a live case charge being lowered on rope into position.

‘It was shot mid storm and went 2.5m deep, the deepest crown I have seen out of the headwall - cant see records of anything deeper? This failed within the storm snow and was Swd, but involved lots of snow...so I’m thinking this clean-out prevented anything bigger as it kept storming after this and buried all crown and debris by the time we got clear skies to see it.’ - R Leong. On August 9, Whakapapa Ski Patrol teams attempted to undertake some high level avalanche control on the Te Heu Heu Valley Headwall at the end of the day. During the mission, the team experienced significant ‘whoompfing’ which communicated across the whole upper mountain of Whakapapa. I was taking photos and was located over 1 km away from the team and clearly heard the settlement race past me - something that is very rare on Ruapehu and I’m not ashamed to say we were all pretty spooked. The guys managed to get one charge on the slope (see photo 4 above) but did not get any significant results.

On the 1 0th of August, the day after this photo, the Whakapapa Patrol Team managed a Size 3 out of a path called ‘Moonsteeps’.

'This failed below multiple ice lenses on a thin layer ofdeveloping facets, but all of this had occurred within the storm snow (prolonged storm). so wasn't a previously formed FC layer which then got buried.’- R Leong.

We then descended back into another couple of days of

Photo 5: The amazing views from the saddle on our way up to ‘Moonsteeps’.

storming and received another ~20cm. On the 1 5th of August, both ski patrol teams started early with plans to test the new load of snow and how well the now deeply buried weak layers would hold up. The day began with groomer transport, light winds, blue skies and the anticipation of some good results from hard work.

Bendy (Brendon Nesbit - Safety Services Manager Turoa) had organised for the helicopter to be at Turoa as early as possible and prior to the machine arriving, the snow safety team had made assessments of the conditions, planned out what explosives would be needed and then briefed the second wave of patrollers once they arrived. This happened simultaneously at Whakapapa.

On this occasion, the Whakapapa team were planning to "borrow" the helicopter after Turoa had finished with it in order to control some really hard to reach start zones in the Pinnacles which needed to be tested with large triggers (half

Photo 6: Pre-control day briefing for the Turoa Ski Patrol team.

sack ANFO shots). This was to prove less than effective - see lessons learned section below.

I was personally tasked with a short mission up into a path we call Lego Land which involved a bit of climbing and some amazing views over the North Eastern flanks of the mountain. Joel and I were successful in deploying the test shots that we had been directed to and started our journey back down into the ski area. We reached the point where we had stashed our skis and started to take our crampons off. At about that point I received a radio call from Customer Relations requesting that I call the Ski Area Manager at Turoa urgently. I turned my phone back on and made the call.

“Andy, we have had a significant (Size 5) result from heli bombing and we need to talk with you and Ross (then CEO) about our next moves”.

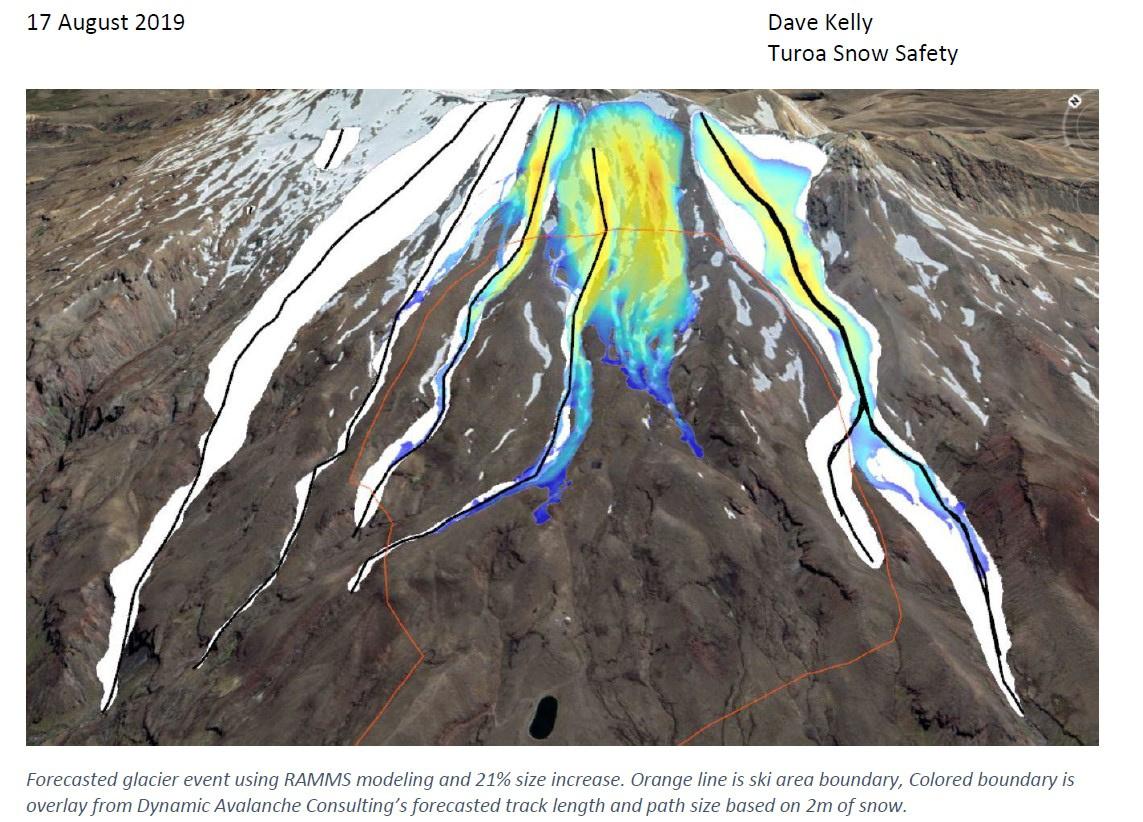

Once back under way, the team managed another significant result - a size 4 from Upper Big Bowl (see photo 7) from another 20kg ANFO case charge. This slide overran the RAMMS models by over 20% and actually cruised right through the ski area and out the bottom boundary again leaving a shear and un-travel-able bed surface in its wake. Fortunately, these were to be the only two significant events for the remainder of the day and the ski area was opened to staff to begin the dig out process.

So what did we learn and what would we want to pass on to the next team dealing with this situation in the future?

Use technology. This control day highlighted to us that the RAMMS modelling was actually pretty solid but, in hindsight, we needed to increase our scenario failure depth. I’m happy to admit that I didn’t foresee a 6m crown depth at the time we were discussing this with our consultants. We would highly recommend all operations consider validating runout distances with RAMMS (or similar) modelling (see photo 8)..

Use all your sources. Although computer modelling has proven to be really useful in backing up our somewhat limited historical records, never forget the wide range of historical sources that might be out there lurking in old facebook pages etc. Photo 1 1 (below) is a screenshot from Facebook with some images of large scale natural avalanche cycles that occurred in the late 70’s.

Interestingly, on the 1 4th of August 201 9, a public observation was logged on the NZ INFOEX platform illustrating a similar scale event (see photo 9).

Tell the stories often. Remember, the earth is 4.543 billion years old. Our ‘historical’ records don’t really scratch the surface so to speak. Question everything you think you know

Photo 7: This image shows the two large start zones, the left hand side being Upper Slider and the right hand one Upper Big Bowl. For scale, the crown on Upper Slider was approximately 6m deep.

about your operational area and don’t be naive in thinking that we have all the records. But also look carefully through your records for more recent trends. Take lots of photos and file them in places where future teams will be able to locate them.

Pre-storm planning is critical. The snow safety teams at Whakapapa and Turoa correctly anticipated the conditions we found on the day (yes the results were larger than we expected) and all personnel were kept out of run out zones.

Always have a plan B. We had planned to share a helicopter between the two operations. In the end, this did not work well as the control work at Turoa took significantly longer than planned to execute (for good reason). This caused a significant delay for Whakapapa.

Infrastructure planning is critical. At the time of constructing the High Noon Express ski lift there were clear indicators that it was located in the path of potential avalanches. The return station was even built with this in mind and slightly recessed into the hillside. In winter 201 8 the avalanche that took out the two top towers of this lift was a size 4 and the slab depth was less than 1 meter. Our modelling now shows that the lift is much more at risk than

Photo 8: The figure above is a composite overlay with a RAMMS model for a 2m crown failure (coloured) and the actual events that we observed on the 15th (white). Dave Kelly.

was previously assumed. Our work to mitigate this risk is ongoing but short of moving the lift we are somewhat hamstrung. Why the start zones above the High Noon Express did not perform on the 1 5th of August 201 9 is unknown but assumed to be due to different weather conditions and exposure to wind at the time the weakness was first laid down.

Photo 10: The lower ski area boundary at Turoa on the 16th ofAugust, a day after two large avalanches were triggered and ran right through the ski area.

Photo 9 (above): Large natural event from below Tukino Peak running down the Mangatoetoenui Glacier taken on the 14th of August 2019. Photo: Simon Edmonds.

Photo 11: Sections of debris were left sitting in the track which bisected the ski area and the friction created during the slide motion left an impenetrable bed surface.