The Equine Veterinary Practitioner

The Official Publication of the New Zealand Equine Veterinary Association

Podiatry

NZERF

The Official Publication of the New Zealand Equine Veterinary Association

Podiatry

NZERF

Joe Mayhew (Editor) 2 Owen Road, Gisborne 4010 evp.editor@gmail.com

Rabecca McKenzie (Convenor)

Emma Gordon (Secretary)

Lotte Cantley

HawkerLuca Panizzi

Mobile: 027 437 3651 Home: 06 927 7263

Rabecca@tevs.co.nz

Shelly Hann

Gareth Fitch

Barbara Hunter Trish PearceLucy Russell

Erica Gee

Lucy Holdaway (NZEVA Executive Rep.)

Papers for publication in The Equine Veterinary Practitioner (EVP) should be sent to the Editor in electronic form. Authors are requested to follow the usual EVP format for the front page of a paper including name(s) and address and email for contact author. The Editor must be made aware of any copyright matters and any appropriate acknowledgments.

Please direct all advertising inquiries to Tony Leggett (NZ Farm Life Media) on 027 4746 093 or tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz A full media kit for the publication is available on request.

The “Equine Veterinary Practitioner” is published by the NZ Equine Veterinary Association (NZEVA) a branch of the NZ Veterinary Association Incorporated (NZVA). The views expressed in the articles and letters do not necessarily represent those of the editorial committee of the NZEVA, the NZEVA executive or the NZVA, and neither NZEVA nor the editor endorses any products or services advertised. NZEVA is not the source of the information reproduced in this publication and has not independently verified the veracity of the information. It does not accept legal responsibility for the truth or accuracy of the information contained herein. Neither NZEVA nor the editor accepts any responsibility whatsoever for the contents of this publication or for any consequences that may result from the use of any information contained herein or advice given herein. The provision is intended to exclude the NZEVA, the NZVA, the editor and the staff from all liability whatsoever, including liability for negligence in the publication or reproduction of the materials set out herein.

WANDA LU (by REMIND) with rider Elise, working ahead of SNORKEL (by I AM INVINCIBLE) with rider Toni, from Isola Stables on early morning training ride at Karioitahi beach.

“I took this photo on 2nd August, 2022 around 7am at Karioitahi beach. The moon was setting, just before the sun rose. I slept at Waiuku in a motorhome with my friend because we were going to photograph meteor showers. But the moon was too bright for that so we went to the beach early in the morning. We were so lucky to meet these horses and people at the beach on such a beautiful day”.

Catherine Song Castor Bay Auckland

Catherine Song Castor Bay Auckland

The EVP Editorial Group would like to invite NZEVAmembers contribute to the photographic art we display on the front covers, so please feel free to send any potential photos to evp.editor@gmail.com. These may be of an artistic, clinical, industry, social or humorous theme as long as they relate to Equidae. We may even spring for a prize for best contribution each year! So get your cameras out, scrutinise your hard disks and contribute.

Brendon Bell (President) nzevapresident@gmail.com 027 484 6378

Lucy Holdaway (Secretary) nzevasecretary@gmail.com 027 541 1294

Grace Reed (Treasurer) Shelly Hann Melissa Sim

Ronan Costello Pip Hendron Alex Fowler

Dentistry

Emergency Management & Horse Ambulance

Katie Kindleysides katiekindleysides@gmail.com Glenn Beeman mountainviewequinenz@gmail.com

Peter Gillespie peter@vetequine.co.nz

Endoscopy Ivan Bridge ivan@vetassociates.co.nz

EVP Journal Rabecca McKenzie Rabecca@tevs.co.nz

Groom Scheme Ivan Bridge ivan@vetassociates.co.nz

Insurance Brendon Bell brendonb@vetsouth.co.nz

Medication Andrew Grierson andrew@aucklandvets.co.nz

Parasitology Holly Blue info@bluebloodequine.co.nz

Young Members Pip Hendron pip.hendron@swvets.co.nz

LIAISON WITH

NZ Equine Health Association Ivan Bridge ivan@vetassociates.co.nz

NZ Equine Research Foundation Tim Pearce timpearce@srvs.co.nz

Racing Authorities Andrew Grierson andrew@aucklandvetcentre.com

Sport Horse Celia Grant vet@helpmyhorse.co.nz

Brendon Bell, NZEVA

President nzevapresident@gmail.comAs equine veterinarians we are in the middle of the busy season now - I hope everyone is coping well with things the silly season throws at us.

I have attended several NZVA MAG (Membership Advisory Group) meetings. Things of note are that we are looking at NZVA Policies (outline of general agreement on a subject) and Position Statements (universal agreement on a subject). Any of these that are outdated will be looked at and deleted if unnecessary or updated. This will be performed across all NZVA SIBs and the executive will be tasked with looking into all equine policies and position statements. I've also been involved in the Veterinary Council (VCNZ) Professional Standard Committee which helps to look at how the code of professional conduct is reviewed and applied. The Code dictates how we all practice on a daily process and I’ve found it interesting to be involved in the process to keep this relevant to clinical practice.

We are looking to secure equine stream speakers for next year's conference. This will be the NZVA centenary conference and will be a MEGA one with other streams, to be held in Wellington. The CPD committee has contacted speakers and are awaiting to hear back regarding confirmation. The conference will have a medical theme and our sessions may be somewhat truncated due to combined plenary sessions with other streams. VetPD are looking to return this year with a lab to be held at Massey, tacked onto the end of the conference, covering topics yet to be confirmed.

You may have noticed emails from the VCNZ regarding a survey on associated veterinary para professionals as the Vet Council looks into reviewing the Veterinarians Act. I have participated in meetings on this review with other SIB representatives and allied para veterinary professions. For equine Vets this legislation could help regulate Equine Dental Technicians in particular, so I encourage you all to participate and complete the survey.

The report in this edition by Peter Gillespie from the Equine Ambulance Trust is very inspiring. The trust has done a great job in fund sourcing then constructing these state-of-the-art Equine Ambulances that we all see at race meetings. This has been a labour of love for those involved over many years and the system we have now is a real credit to all this hard graft. Tremendous effort.

As this issue comes out close to Christmas, I wish all members good fortune over the holiday period. I hope you are not too busy over the festive season and can find time to enjoy the festivities with friends and family.

Kind regards, Brendon Bell nzevapresident@gmail.com

Arango-Sabogal JC et al. Date of birth and purchase price as foals or yearlings are associated with Thoroughbred flat race performance in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Vet Rec Open. 2022 Dec; 9(1): e43.

Purchas price as foal or yearling and performance figures were studied for 6,666 [UK] and 9,456 [IRE] horses in flat racing by the end of their second and third years of life. Prize money and prize money per start decreased with each additional day beyond 1st January (official TB foal birth date in UK & IRE) that the foal was born on. Purchase price was negatively associated with the number of races run, while it was positively associated with prize money and prize money per start by the end of the third year of life. Differences were more marked among males than females. The more expensive foals and yearlings ran fewer races but earned more prize money and prize money per start as 2- and 3-year-old racehorses than less expensive foals and yearlings. These findings may help inform management practices aiming to maximise horses' racing performance potential and increase financial returns.

Like many of you, I certainly have experienced incivility in the workplace, and heaven forbid, I may have been guilty of it myself! Incivility may be thought of as a forerunner of bullying. Displays are usually rude and discourteous, displaying a lack of regard for others and include interruptions and use of condescending tones and unprofessional terms of address (J Occup Health Psychol 2009; 14(3): 272-288) Amy Irwin and colleagues from the University of Aberdeen recently studied the frequency, impact and mitigation strategies for problematic incivility in veterinary practices in the UK (Vet Rec. 2022; 191(7): e2030). They determined that workplace incivility was very common and that incivility from senior colleagues predicted increased turnover intention for veterinary surgeons and predicted reduced job satisfaction for veterinary nurses. Also, client incivility received from clients increased the risk of professional burnout. Although only suggestions, the authors considered that veterinary practices should outline expectations in terms of civil behaviour, provide additional staff within problematic client consultations, and arrange regular reflective team meetings, all to help prevent incivility interfering with a happy, productive professional environment. Only on very large properties with quite valuable animals is equine blood typing likely to be economically feasible. Notwithstanding, most clinicians will at times face a need for blood/RBC transfusion – not simply plasma, available commercially – and we not always are well prepared for this. Fortunately, Camilla Jamieson and colleagues from Equine Veterinary Medical Center, Doha, Qatar have given us a nice review of blood transfusions in horses (Animals. 2022; 12(17): 2162) that covers the physiology and pathophysiology of conditions requiring transfusion, as well as step-by-step transfusion guidelines for practitioners. It has been a while since I have had to give blood/RBCs to a foal or whole blood to an adult horse, so this paper is a timely ready reckoner on the process. Notwithstanding, there are a few here some aides-mémoire that may be of use to readers.

- Only ~10 % of horses have naturally occurring alloantibodies, so crossmatch testing before blood transfusion is not always performed.

- Survival times for compatible RBCs is ~20-30 days.

- Survival time for incompatible RBCs is ~3-5 days.

- Laboratory-based complete major and minor compatibility testing for horses is not routinely available.

- A slide agglutination test (SAT) can be performed in many labs but just tests minor compatibility (donor serum vs recipient RBCs).

- It is haemolytic not agglutinating antibodies that are the major culprit in neonatal isoerythrolysis (NI) and in immunemediated haemolytic anaemia (IMHA).

- RBCs coated in antibodies, as in NI and IMHA, are very fragile and can lyse with any further minor insult.

- Whether blood typing, cross matching or going blind, it is the TPR-response of the recipient over the first ~15 minutes of slow administration that determines whether or not one is doing the best for the patient.

I am sure we will be reading much more in future about genetic manipulation, both for treating genetically related disorders and in detecting unlawful practices. Tozaki et al. have been looking at means to detect fraudulent forms of genetic manipulation in TB racehorses and their recent results (Genes. 2022; 13(9): 1589) indicate that gene-editing tests such as searches for single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) are useful to identify genetically modified racehorses, such as foals that have been produced by somatic cloning or by embryo transfer.

I am poor at interpreting statistics in papers, though I do tend to remain rather sceptical of claims made. However, we can get really excited about a new published finding indicating that treatment X is statistically significantly superior to a standard therapy Y [P ≤ 0.01]. Well, because of the huge misunderstandings associated with interpretations of P-values, confidence intervals and other statistical analytes, some journals have banned their publication. In fact the litany of 25 misinterpretations of such a finding [P ≤ 0.01] is quite unbelievable, as outlined in a paper by a large group of international experts in statistics and epidemiology (Eur J Epidemiol. 2016; 31: 337–350). This is not a paper for reading in bed, but a couple of Mayhewisms taken from the paper were that irrespective of any P-value, the hypothesis is still either right or wrong, depending on how well data measurement, collection and analysis followed correct processes, and what error-prone assumptions were accepted. And far too often we deduce ‘no difference’ from ‘no significant statistical difference’; WRONG.

But if readers are interested in delving further in to stats, The ASA Statement on p-Values (Am Statist 2016; 70(2): 129133) gives far more critique than the editor is capable of and addresses six (mis)conceptions and (mis)uses of the P-value: 1. P-values can indicate how incompatible the data are with a specified statistical model.

2. P-values do not measure the probability that the studied hypothesis is true, or the probability that the data were

produced by random chance alone.

3. Scientific conclusions should not be based only on whether a P-value passes a specific threshold.

4. Proper inference requires full reporting and transparency.

5. A P-value, or any measure of statistical significance, does not measure the size of an effect or the importance of a result.

6. By itself, a P-value does not provide a good measure of evidence regarding a model or hypothesis.

And while on the subject of trying to interpret data sets and association verses causality, I was interested in a commentary by a colleague James Meyer on a recent paper by Bennett and Parkin on risk factors for sudden death in racehorses appearing ahead of print at J Am Vet Med Assoc 2022 Oct 20; 1-7. The paper authors were quoted as saying that the use of furosemide (Lasix) in a race increases the risk by ~62%. This was based on the adjusted odds ratio (1.62; 1.01 to 2.61, p= 0.047), being a relative risk. Meyer points out that the data actually indicates an absolute risk of 0.005%, being rather less dramatic than 62%. On this basis, one more horse receiving furosemide would die, compared to those horses not receiving furosemide, over 20,000 race starts. Perhaps this is ano example of my simple dictum of wanting to look at the primary data rather than some derived statistic? So you think that we need more vets in our discipline and

recent graduates are ill-prepared for your practice discipline? Well, why not suggest an apprenticeship route to graduating? It appears that the UK National health Service is working towards adding such a route to graduating as a human doctor, so why not vets? This has been mooted in the Vet Rec recently by vet consultant Matt Ashford who confirms that standards of training and exams could remain the same, though there likely would be a shift to species specialisation within the programme. It would likely be applicable to only those practices with a high case load and staffing but imagine a few keen young horse industry workers being able to assist and learn on employment with say 2 days a week taking courses, both on-line and on resident teaching practicals. Wouldn’t they more likely stay in the industry? Worth pondering on, don’t you think?

I trust the spring has been enjoyable and readers can manage to take some time off during the summer period.

Kia kaha, nä Joe evp.editor@gmail.com

The

The British Equine Veterinary Association has made available to NZEVA Members much of its resource material including full current EVE and EVP papers, podcasts and discussions. You do not need to be a BEVA member to have a BEVA account - it's just you get more if you're a member. Registering as a NZEVA Member on the BEVA website will allow you to access resources, book CPD including BEVA Congress, and sign up for a BEVA membership.

To set up an account please fill in details and press the Register button on the login page here: https://www.beva.org.uk/Login?returnurl=%2fMembership%2fInternational-Partners

Proximal enteritis is a differential for horses presenting with signs of colic, systemic inflammatory response and gastric reflux, but is not commonly described in New Zealand. This report describes a case of suspected proximal enteritis and secondary mesenteric venous thrombophlebitis in a 7-yearold Welsh pony gelding. A full reference listing on proximal enteritis is offered.

A 7-year-old, 300kg Welsh pony gelding presented to Massey University Equine Veterinary Clinic with a history of colic and progressive signs of systemic illness persisting over 24 hours. There was no reported pyrexia or diarrhoea. Approximately 10 hours prior to admission, the gelding was seen by the referring veterinarian. At this visit, the gelding had marked tachycardia (88 bpm) and was given 2 mg/kg flunixin IV and 2 L of enteral fluid with electrolytes via nasogastric tube.

On presentation, the gelding was quiet with marked tachycardia (120 bpm) and tachypnoea (88 brpm). Mucous membranes were hyperaemic, dry with a CRT of 3 seconds. Jugular fill was delayed, borborygmi were absent in all quadrants, rectal temperature was 37.6 oC, and the digital pulses were difficult to palpate. The pony’s body condition score was estimated to be 7/9 (Henneke et al., 1983)

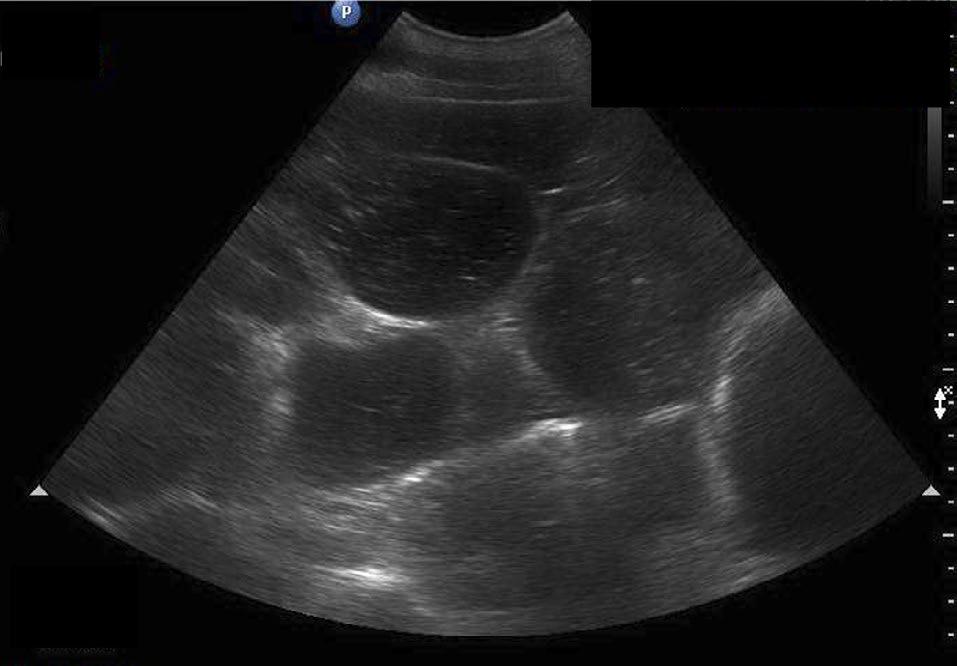

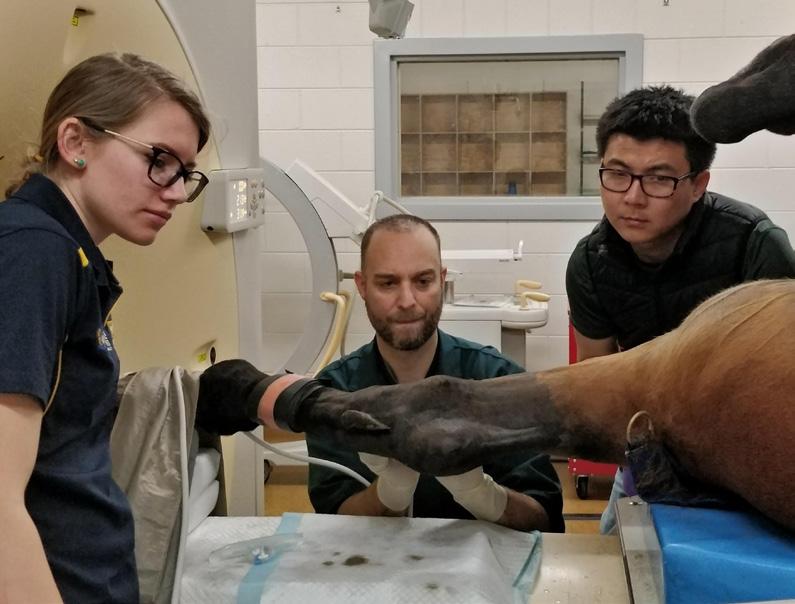

An abdominal ultrasound of the patient was performed using the “fast localised abdominal sonography of horses” (FLASH) approach (Busoni et al., 2011). The stomach was distended with fluid, with the caudal gastric axis extending to the 15th intercostal space. Nasogastric intubation was performed immediately, which liberated spontaneous, malodorous, dark green gastric reflux with a total net volume of 20 L. Continued FLASH examination revealed multiple, distended, amotile loops of small intestine (SI) in all quadrants of the abdomen (Figure 1); these loops measured 6-7 cm in diameter, and all wall thicknesses measured <3mm. There was a moderate increase in anechoic peritoneal fluid. The heart rate reduced to

108 bpm after gastric decompression and the pony’s attitude became increasingly dull. Blood analysis stall-side showed a packed cell volume of 62%, total protein of 88 g/L and lactate of 4.6 mmol/L. A jugular vein catheter was placed and a 6L bolus of Hartmann’s solution was administered. Muscle fasciculations developed and progressively worsened; 0.33 mg/kg xylazine was administered IV.

Abdominocentesis was performed and the peritoneal fluid obtained was serosanguinous in colour with a lactate of 12.5mmol/L. Venous blood gas analysis and biochemistry were performed following fluid resuscitation. These showed hypochloraemia (92 mmol/L), hyperglycaemia (11.1 mmol/L), hyperlactatemia (9.91 mmol/L), azotaemia (urea 17.6 mmol/L, creatinine 373 µmol/L) and an increased anion gap (20 mmol/L). Palpation per rectum was not performed due to the small patient size.

Dehydration of the patient was estimated to be at least 10%. The marked tachycardia persisted following gastric decompression, likely due to a combination of visceral pain and hypovolaemia. Additionally, the patient met the clinical criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in adult horses (Roy et al., 2017), but, routine haematology

was not assessed in this case. The large volume of gastric reflux was indicative of a mechanical or functional small intestinal obstruction. Ultrasound findings were suggestive of diffuse small intestinal dysfunction, and intestinal hypomotility was supported by the absence of borborygmi on auscultation. High peritoneal fluid lactate (12.5 mmol/L) and peritoneal fluid lactate to blood lactate (PFL: BL) ratio of 2.7 (using initial blood lactate value), in combination with grossly serosanguinous peritoneal fluid, was highly suggestive of a strangulating intestinal lesion requiring surgical intervention (Shearer et al., 2018, Delesalle et al., 2007).

The azotaemia was thought to be a combination of pre-renal and renal, with the history of high dose non-steroidal antiinflammatory (NSAID) medication, along with hypovolaemia and SIRS putting this case at increased risk for acute kidney injury (Divers, 2022). No urine was passed during patient evaluation.

Strangulating and ischaemic lesions of the SI are a surgical emergency. Although exploratory laparotomy was offered, this was declined by the client due to financial considerations and the guarded prognosis for long-term survival (Delesalle et al., 2007, Hassel et al., 2009, White, 2017c). Thus, humane euthanasia was elected.

A diagnosis of mesenteric (jejunal to ileal) thrombophlebitis was made following gross and histological examination postmortem. No small intestinal pedunculated lipoma, volvulus, entrapment, displacement, intussusception, mechanical obstruction, or perforation were discovered. Grossly, the SI was diffusely distended with watery green fluid (most consistent with a functional ileus), with one exception, there was one 30cm segment of the ileum that had additional gross lesions. These included serosal haemorrhage, mural thickening and a dark red to grey appearance of the mucosa. Based on the above, a diagnosis of proximal enteritis was made.

Microbial polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on fresh jejunal contents, the sample tested positive for Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin-A gene. The sample was PCR negative for Salmonella sp., C. difficile, Lawsonia intracellularis, C. perfringens NetF positive strains, and equine coronavirus.

Differentiating between a strangulating small intestinal lesion and proximal enteritis can be challenging due to similar clinical presentations and diagnostic findings (Arroyo et al., 2017). Common physical exam findings for proximal enteritis include abdominal pain, pyrexia, tachycardia, hyperaemia and marked gastric reflux (Archer, 2017). Typically, proximal enteritis cases have abdominal pain that is replaced with dullness following gastric decompression, compared to small intestinal obstruction cases that tend to become increasingly painful despite gastric decompression (Archer, 2018).

Proximal enteritis, otherwise known as duodenitis proximal

jejunitis (DPJ), is a syndrome of sporadic, acute inflammation of the duodenum and proximal jejunum. Overseas, the severity of this condition has been shown to range geographically (Steward et al., 2020). Anecdotally, there are also variations in prevalence geographically, yet there is a paucity of published reports of proximal enteritis in New Zealand horses.

The aetiology of proximal enteritis remains unknown, however, infectious agents such as C. difficile, C. perfringens, mycotoxins, and Salmonella spp. have been hypothesised (Arroyo et al., 2018, Edwards, 2000), all being anecdotal other than C. difficile. Inoculation of C. difficile toxins in healthy horses is reported to induce clinical signs and histological lesions consistent with naturally occurring proximal enteritis (Arroyo et al., 2017). In New Zealand, definitive diagnosis of these clostridial pathogens is limited due to the lack of ELISA testing for the different clostridial toxins (Uzal et al 2022). Alternatively, identification of clostridial DNA via PCR is available in New Zealand, as was performed in this case. Clostridium spp. can colonise the gastrointestinal tract of healthy horses, thus, a positive PCR result for clostridial toxins should be interpreted with caution as gene presence does not equal causation of disease (Schoster et al., 2012). In healthy colonised individuals, it is suggested that toxigenic strains of Clostridium spp. do not produce disease due to inhibitory actions of protective commensal microbiota (Mullen et al., 2018). One study investigating the presence of C. difficile and C. perfringens in different intestinal compartments of 15 healthy horses did not identify C. perfringens in any small intestinal compartment of the enrolled horses (Schoster et al., 2012). The results of this study are consistent with previous studies reporting a low prevalence of C. perfringens shedding in healthy adult horses. Thus, whether C. perfringens Type A in the present case indicates aetiological cause of proximal enteritis or simply is a result of opportunistic proliferation of this organism is unclear.

Horses with severe, acute gastrointestinal disease often develop SIRS as a result of systemic exposure to lipopolysaccharide (i.e., endotoxin) of enteric gram-negative bacteria (Archer, 2018). In both human and veterinary medicine, SIRS is known to have many deleterious sequelae, including vascular dysregulation, glucose and insulin dysregulation, coagulopathies, and multiple organ dysfunction (Dallap Schaer and Epstein, 2009). Additionally, laminitis is a common sequalae of SIRS in horses. Hyperglycaemia, as was observed in this pony, can be seen in equine patients with SIRS and is a negative prognostic indicator (Archer, 2018, Hassel et al., 2009). Horses with SIRS have a tendency to become hypercoagulable, which favours thrombosis development (Dallap Schaer and Epstein, 2009). Furthermore, obese, insulin dysregulated horses can be hypercoagulable compared to healthy controls (Lovett et al., 2022). As such, our patient might have had an increased risk for thrombosis being a predisposed breed for insulin dysregulation (Welsh pony) and being overweight (BCS 7/9). Importantly, although the mesenteric thrombophlebitis was significant in this case, the authors consider that it was most likely secondary to a SIRS-associated coagulopathy, as opposed to being the

primary inciting lesion of non-strangulating intestinal ileus and ischaemia.

The diagnosis of proximal enteritis was made at post-mortem. This was strengthened when jejunal fluid tested PCR positive for C. perfringens enterotoxin-A gene. False-negative PCR results for Salmonella spp. and equine coronavirus is possible in this case. However, due to the high sensitivity of PCR testing, and the clinical presentation of this pony not being consistent with the literature for equine coronavirus, it remains an unlikely aetiologic agent (Pusterla, et al,. 2012, Pusterla, et al., 2009). Additional infectious disease testing on faeces could have aided in further elucidating the role of these pathogens, for example, faecal PCR for equine coronavirus and culture of faeces for Salmonella spp. Salmonella spp. can be intermittently shed in the faeces of infected horses (Shaw et al., 2018), therefore, repeated faecal testing would have been valuable, although not possible in this case.

Blood lactate in normal horses is <1.5mmol/L, with peritoneal fluid lactate always less than venous blood lactate in healthy horses (Moore et al., 1977). Peritoneal and plasma lactate are significantly higher in colic cases with intestinal ischaemia (~8.45 mmol/L) compared to non-strangulating obstruction cases (~2.09 mmol/L), and peritoneal fluid lactate >9.4 mmol/L is associated with non-survival (Seahorn et al., 1992, Moore et al., 1977). Peritoneal fluid lactate (PFL) to blood lactate (BL) ratio (PFL: BL) > 2 indicates a strangulating intestinal lesion (Shearer et al., 2018). Serosanguinous peritoneal fluid is more likely to be seen with strangulating compared to non-strangulating small intestinal lesions. However, in severe cases of proximal enteritis diapedesis can occur, also resulting in serosanguinous peritoneal fluid (Shearer et al., 2018). With no evidence of a strangulating lesion on post-mortem examination, this case represents the potential limitations with interpreting peritoneal fluid lactate in severe, acute colic cases.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates how severe proximal enteritis can be difficult to differentiate from strangulating intestinal lesions in the horse. While the significance of enterotoxigenic C. perfringens in this case is difficult to define due to test limitations in New Zealand, it remains a plausible aetiologic agent.

Thank you to Dani Aberdein and Emma Gulliver, Veterinary Pathologists, for the detailed post-mortem examination, anda special thanks to Luca Panizzi, Equine Surgeon, for his help with the case.

Archer DC. 2017. Diseases of the small intestine. Ch 52 in The Equine Acute Abdomen, 3rd Ed, AT Blikslager, NA White II, JN Moore and TS Mair, Eds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. NJ. 704-736.

Arroyo LG, Costa MC, Guest BB et al. 2017. Duodenitis-Proximal Jejunitis in Horses After Experimental Administration of Clostridium difficile Toxins. J Vet Int Med, 31, 158-163.

Arroyo LG, Gomez DE & Martins C. 2018. Equine duodenitis-proximal jejunitis: A review. Canad Vet J, 59, 510-517.

Busoni, V., Busscher, V. D., Lopez, D., Verwilghen, D. & Cassart, D. 2011. Evaluation of a protocol for fast localised abdominal sonography of horses admitted for colic. Vet Rec, 188, 77-82.

Dallap Schaer, B. L. & Epstein, K. 2009. Coagulopathy of the critically ill equine patient. J Vet Emerg Crit Care, 19, 53-65.

Delesalle, C., Lefere, L., Deprez, P., Dewulf, J., Lefebvre, R. A., Schuurkes, J. A. J. & Proot, J. 2007. Determination of lactate concentrations in blood plasma and peritoneal fluid in horses with colic by an accusport analyzer. J Vet Int Med, 21, 293-301.

Divers, T. J. 2022. Acute Kidney Injury and Renal Failure in Horses. Vet Clin Nth Mer Equine Pract, 38, 13-24.

Dunkel, B., Chan, D. L., Boston, R. & Monreal, L. 2010. Association between Hypercoagulability and Decreased Survival in Horses with Ischemic or Inflammatory Gastrointestinal Disease. J Vet Int Med, 24, 1467-1474.

Edwards, G. B. 2000. Duodenitis-proximal jejunitis (anterior enteritis) as a surgical problem. Equine Vet Edu, 12, 318-321.

Freeman, D. E. (2000). Duodenitis-proximal jejunitis. Equine Vet Edu, 12(6), 322–332.

Hassel, D. M., Hill, A. E. & Rorabeck, R. A. 2009. Association between hyperglycemia and survival in 228 horses with acute gastrointestinal disease. J Vet Int Med, 23, 1261-1265.

Henneke, D. R., Potter, G. D., Kreider, J. L., & Yeates, B. F. 1983. Relationship between condition score, physical measurements and body fat percentage in mares. Equine Vet J. 15(4), 371-372.

Johnstone, I.B., & Crane, S. 1986. Haemostatic abnormalities in horses with colic — Their prognostic value. Equine Vet J, 18: 271-274.

Lovett, A.L., Gilliam, L.L., Sykes, B.W. and McFarlane, D., 2022. Thromboelastography in obese horses with insulin dysregulation compared to healthy controls. J Vet Int Med, 36(3), 131-1138.

Moore, J., Traver, D. & Turner, M. 1977. Lactic acid concentration in peritoneal fluid of normal and diseased horses. Res Vet Sci, 23, 117-118.

Mullen, K.R., Yasuda, K., Divers, T.J. and Weese, J.S., 2018. Equine faecal microbiota transplant: Current knowledge, proposed guidelines and future directions. Equine Vet Edu, 30(3), 151-160.

Pusterla, N., Mapes, S., Wademan, C., White, A., Magdesian, K. G., Ball, R., Sapp, K., Burns, P., Ormond, C., Butterworth, K., & Bartol, J. 2012. Emerging outbreaks associated with equine coronavirus in adult horses. Vet Microbiol, 162, 228–231.

Pusterla, N., Mapes, S., Magdesian, K. G., Byrne, B. A., Hodzic, E., & Jang, S. S. (2009). Use of quantitative real-time PCR for the detection of Salmonella spp. in fecal

samples from horses at a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet J, 186(2), 252–255.

Roy, M. F., Kwong, G. P. S., Lambert, J., Massie, S. & Lockhart, S. 2017. Prognostic Value and Development of a Scoring System in Horses With Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. J Vet Int Med, 31, 582-592.

Sanchez C. 2018. Duodenitis-Proximal Jejunitis, in Ch 12 Disorders of the Gastrointestinal System, Equine Internal Medicine, 4th Ed, Reed SM, Bayly WM & Sellon DC eds. Elsevier, St. Louis, Mo. 738-741.

Seahorn, T. L., Cornick, J. L. & Cohen, N. D. 1992. Prognostic Indicators for Horses with Duodenitis‐Proximal Jejunitis 75 Horses (1985–1989). J Vet Int Med, 6, 307-311.

Schoster, A., Arroyo, L.G., Staempfli, H.R., Shewen, P.E. and Weese, J.S., 2012. Presence and molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium perfringens in intestinal compartments of healthy horses. BMC Vet Res, 8, 1-6.

Shaw, S. D., & Stämpfli, H. (2018). Diagnosis and Treatment of Undifferentiated and Infectious Acute Diarrhea in the Adult Horse. Vet Clin Nth Amer Equine Pract, 34(1), 39–53.

Shearer, T. R., Norby, B. & Carr, E. A. 2018. Peritoneal Fluid Lactate Evaluation in Horses With Nonstrangulating

Versus Strangulating Small Intestinal Disease. J Eq Vet Sci, 61, 18-21.

Steward, S. K. T., Hassel, D. M., Martin, H., Doddman, C., Stewart, A., Elzer, E. J. & Southwood, L. L. 2020. Geographic Disparities in Clinical Characteristics of Duodenitis–Proximal Jejunitis in Horses in the United States. J Equine Vet Sci, 93, 103192

Uzal, F. A., Arroyo, L. G., Navarro, M. A., Gomez, D. E., Asín, J. & Henderson, E. 2022. Bacterial and viral enterocolitis in horses: a review. J Vet Diag Invest, 34, 354-375.

Van Den Boom, R., Butler, C. M. & Sloet van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan, M. M. 2010. The usability of peritoneal lactate concentration as a prognostic marker in horses with severe colic admitted to a veterinary teaching hospital. Equine Vet Edu, 22, 420-425.

White II, N. A. 2017a. Decision for Surgery and Referral. Ch 24 in The Equine Acute Abdomen, 3rd Ed, AT Blikslager, NA White II, JN Moore and TS Mair, Eds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. NJ. 285-288.

White II, N. A. 2017c. Prognosticating Equine Colic. Ch 25 in The Equine Acute Abdomen, 3rd Ed, AT Blikslager, NA White II, JN Moore and TS Mair, Eds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. NJ. 289-300.

Readers might enjoy viewing video lectures on the following topics at the two links below. These are produced for the Beaufort Cottage Educational Trust and sponsored by the Gerald Leigh Family Trust.

Welcome and introduction - Nick Wingfield Digby

Sales selection - The trainer's view point - Sir Mark Prescott

The Sales Exam - The veterinary viewpoint - Mike Shepherd

Do foal injuries and diseases compromise sales and racing performance - Celia Marr

Radiography at the Sales - Are findings associated with future performance Pt1 - Debbie Spike-Pierce

Radiography at the Sales - Are findings associated with future performance Pt2 - Debbie Spike-Pierce

Does conformation affect gait - Objective assessmentRenate Weller

Genomics and performance profiling - Where are we heading - Des Leadon

9. A personal view on producing and selecting horses for racing and breeding - Luca Cumani

1. Radiographic findings in Juvenile Orthopaedic DiseaseDebbie Spike Pierce

2. Soft tissue injuries of the foot are there red flags on plain radiography - Marianna Biggi 3. Has advanced imaging changed the management of proximal suspensory desmitis - Sue Dyson 4. Imaging & clinical management of suspensory branch injury in racing thoroughbreds - Pete Ramzan 5. Third phalangeal cysts in the Thoroughbred RacehorseTom O'Keeffe

6. Imaging the equine back - Marianna Castro Martins 7. Fractured ribs - Diagnosis and prognosis - Billy Fehin 8. Pelvic ultrasonography - Sarah Boys Smith 9. Sub clinical imaging findings in the elite sport horseHow do we determine relevance - Sue Dyson

nzevasecretary@gmail.com

As part of the NZEVA executive’s role, we are asked to consider, comment, and advise on a range of topics affecting equine practitioners including policy review, current equine welfare concerns, member resources, and current issues being experienced by practitioners. Where appropriate we consult NZEVA/NZVA members with expertise in the relevant area, usually via our sub-committees. Although many of these matters are brought to us by scheduled review within our subcommittees, or delegated to us by the NZVA, we also receive correspondences from equine practitioners directly throughout the year. If there are topics affecting you in equine practice that you would like to raise, the following are the best ways to get in contact: Email nzevapresident@gmail.com or nzevasecretary@gmail. com. Currently these are attended to by President Brendon Bell and Secretary Lucy Holdaway.

• Contact any member of the executive in person: the current members are listed on our NZVA SIB page

(https://www.nzva.org.nz/branches/equine/) and at the front of each EVP issue.

You can also contact us to express an interest in being involved with the NZEVA executive; we require new members annually as we rotate through three-year cycles. Monthly meetings are held over ZOOM in the evening with the AGM being held in person at conference each year. We also have regular correspondence, mostly via email, between meetings.

If you would like to be more involved in equine collegial discussion on mostly clinical cases, Rabecca Mackenzie has set-up the ‘New Zealand Veterinary Practitioner Group’ on Facebook to support EVP and give NZ vets working with horses a place to get feedback on a variety of unusual and routine cases and procedures. If you would like to join, please contact Rabecca via Facebook or email myself. Existing members of the group can also invite their friends to the group; verification they are a vet working in New Zealand will be made before new members can join.

•

•

•

•

•

• Digital Radiography

• Ultrasonography

• Scintigraphy (Bone Scan)

• Shockwave Therapy

Equine endometritis is a significant problem in breeding mares and causes major financial losses for the equine industry due to loss of income at sales and increased veterinary cost. Equine endometritis is diagnosed via an endometrial sample such as a swab, cyto-brush or low-volume lavage taken during estrus and submitted for both cytology as well as aerobic microbial culture. To increase the sensitivity of the culture, most samples are taken in late estrus, however, to improve the breeding efficiency, clients and veterinarians are expecting a short turnaround time to allow the mare to be bred on the same cycle if the sample comes back clean. Because of this time constraint and the relative long turnover time when endometrial samples are sent to a commercial laboratory, many equine practitioners will perform in-house microbial cultures.

Most practitioners use a combination of MacConkey, blood, and Brilliance™ chromogenic agar plates to allow for easy and quick identification of the most cultured microbes such as S. zooepidemicus, E. spp. in house. Once the bacteria have been identified some practitioners treat the mare without sensitivity testing, some perform sensitivity testing in house and others submit the culture plate to a commercial laboratory.

Leigh de Clifford BVSc CertAVP PGDipVPS MVSc Barbara Hunter DVM MS DAVCS-LA

362 Hinuera Road West Matamata (07) 888 8193 matamatavets.co.nz

samples to Sydney, NSW, Australia for capsule typing.

For a limited time ISELP are offering a selection of Free Lectures that are excerpts from the 2019 ISELP Sports Medicine & Rehabilitation Module. Since EVP press time, more videos may be added.

• Improving Radiology of the Hock - Kurt Selberg

• Radiology of the Stifle - Sarah Puchalski

• Shoeing - Stephen O'Grady

• Equine Rehabilitation: Can We Make A Difference? - Melissa King

• Tendon and Ligament Injury with an Eye on Rehabilitation - Duncan Peters

As well as several GLOBAL SPONSOR

Liquid supplement containing Glucosamine, Chondroitin & Biotin suspended in Omega Oil for bone & joint health,

Dear Colleagues.

Did you know that you are eligible to apply for EVP funds to assist you in obtaining equine veterinary experience, training, travel, CPD etc? This is an annual sum of money is set aside each year by the NZEVA EVP Editorial Group to establish a Continuing Education (CE) fund.

These funds can be for use within Aotearoa. Possible uses of funds include attending the NZVA/ NZEVA conference or short courses, spending time at specialist equine clinics and learning new skills from other (non-clinical) sources e.g., veterinary pathology laboratory.

The two main purposes of this fund are:

• facilitating continuing education and/or specialist training for all paid up NZVA members and EVP Editorial Group members

• disseminating information resulting from such funding that is of benefit to New Zealand equine practitioners through publication in the Equine Veterinary Practitioner journal

Applicants seeking assistance from the CE fund must adhere to the following guidelines:

Added nutrients per 30mls of oil (minimum):

Crude Fat 85% Omega 3 2208 mg

Vitamin A 4050 iu Biotin 4.9 mg

Vitamin D 255 iu Niacin 5.6 mg

Vitamin E 45 mg Calcium Pantothenate 6.2 mg

Vitamin B1 1.05 mg Folic Acid 0.12 mg

Vitamin B2 1.3 mg Selenium 0.1mg

Vitamin B6 0.55 mg Glucosamine Sulphate 2010 mg

Vitamin B12 13 µg Chondroitin Sulphate 501 mg

Omega 6 3948 mg

1. Present a complete budget for the proposed CE project and identify all sources of funds being sought and the planned use of any funds awarded from this fund.

2. Demonstrate that funds awarded under this scheme were used for the stated purpose.

3. Normally present a verbal report to the NZEVA EVP Editorial Group at a convenient EVP meeting held after completion of the CE project, or at the next NZEVA Annual Conference.

4. Within 60 days of the applicant completing, and/ or returning to NZ from, the CE project, submit to the Editor of the EVP a concise report of the project, identifying key new practical items of interest and value to NZ equine practitioners.

5. Applications can be made in writing to and will be assessed by two members of the EVP Editorial Group [currently JM and BH], who are NOT eligible for funding.

6. The application must include a signed statement: “I have read and understand my obligations to the EVP Editorial Committee.”

7. Approved applications can access up to 75% of awarded funds prior to undertaking the proposed travel. The remaining 25% will be paid upon receipt of an acceptable written report.

8. Except in exceptional cases, the amount awarded to any individual applicant will not exceed 50% of the available funds.

The organisations currently represented on the New Zealand Horse Ambulance Trust [NZHAT] and their representatives are:

• Racing Integrity Board: Mike Godber (Chairman)

• New Zealand Thoroughbred Racing: Alice Riggins

• Harness Racing New Zealand: Liz Bishop

• Equestrian Sports New Zealand: Wally Niederer

• New Zealand Equine Veterinary Association: Peter Gillespie & Murray Brightwell.

In August of this year Bill Bishop stepped down as one of the two NZEVA representatives on the Trust although he continues to be actively involved with fund-raising.

The Trust employs a part-time operations and marketing manager and five part-time ambulance drivers.

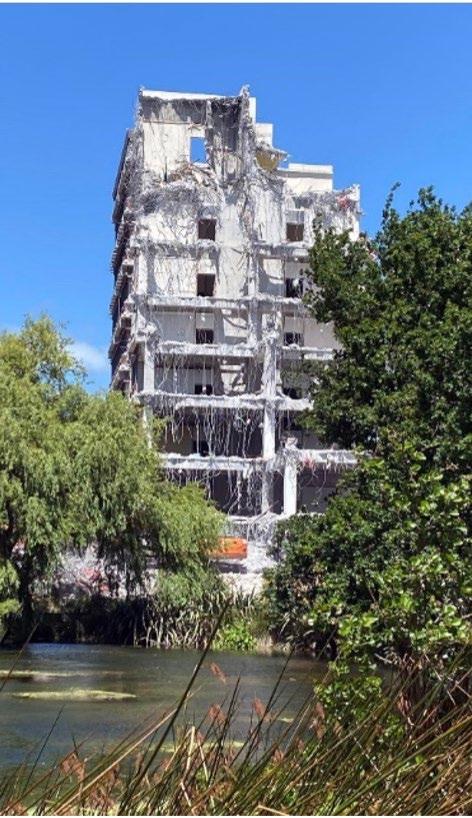

It is almost four years to the day since the first ambulance deployment at the 2018 New Zealand Cup Day at Riccarton. Over this period, NZHAT has funded the construction and operation of a further eight ambulances, including purchase of nine Ford Ranger tow-vehicles.

The Trust has sold one ambulance to Canada, and we are currently negotiating the sale of two units to Western Australia. The nine ambulances are currently situated at:

• Auckland: Alexandra Park & Pukekohe

• Waikato: Matamata & Cambridge

• Taupo: National Equestrian Centre

• Central Districts: Palmerston North (Awapuni)

• Canterbury: Christchurch (Addington

Raceway & Majestic’s Yaldhurst Depot)

• Otago/Southland: Invercargill (Ascot Park)

During the 2021/22 season, ambulances attended 546 race meetings, 95 NZTR trial meetings and 20 ESNZ events. We were involved with nine SPCA welfare rescues and 22 nonrace day horse transfers. Many of the latter were the transfer of injured horses to and from veterinary referral centres. Most of our operational funding - $260,000 in the 2021/22 season - comes from NZTR and HRNZ, and we continue to engage with ESNZ to increase their financial contribution.

The NZHAT continues to advance the NZEVA’s animal welfare role within the New Zealand equine industry. The Trust is currently in discussions with Fire and Emergency NZ to fund technical rescue equipment throughout the country; currently there are only two FENZ brigades (Silverdale & Kumeu) equipped to attend large animal rescues.

NZHAT are looking to raise $250,000 to procure and distribute 20 sets of rescue equipment and two sets of training equipment (including full-sized horse mannequins) so that both FENZ and NZEVA members are better trained and resourced to work together in this space.

NZHAT are aware that of the important role NZEVA members play in ambulance deployments and the need for good lines of communication with those veterinarians working at race meetings and equestrian events.

There is still work to be done but I’m confident we can continue the momentum of the last four years.

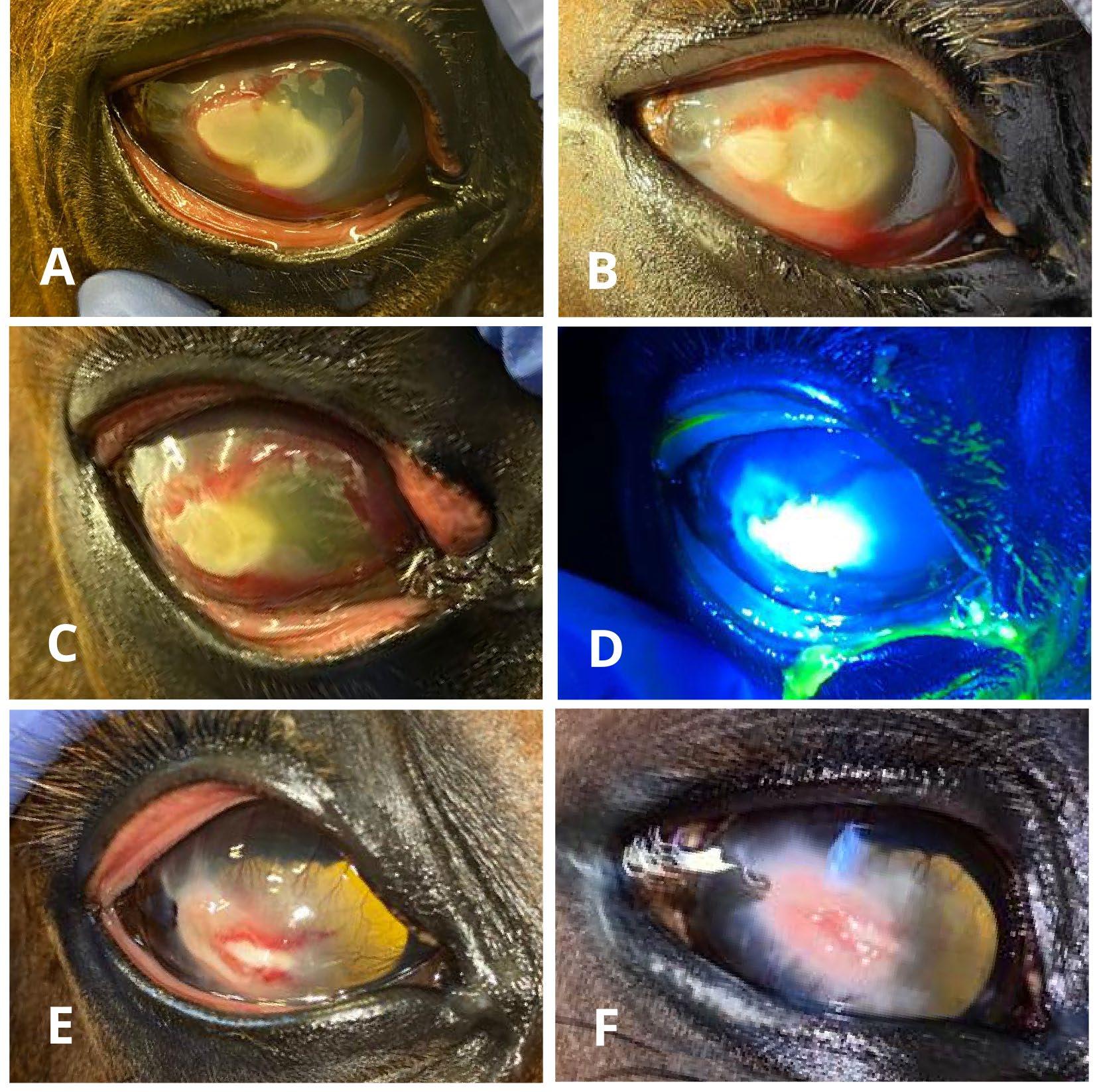

Quere E

Complications

with Superior and Inferior Subpalpebral Lavage Treatment Systems Placed in 61 Equine Eyes (2004-2021). J Equine Vet Sci. 2022: 104076. https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35830905/

Sixty horses were included in the study representing 61 sub-palpebral lavage (SPL) treatment administration systems. Median duration of SPL treatment was 7.5 days. Uneventful outcomes occurred in 53 cases (87%) and complications were recorded for seven upper eyelid systems (23%) and one complication for lower eyelid systems (4%). The easier placement and removal and the possibly lower recorded frequency of complications

All you need to do is write a clinical report that is published in the EVP, and your contribution may be eligible for one of several prizes of $150.00 that the EVP has available each year.

The EVP Editorial Group wish to promote the sharing of your interesting cases and practice tips with the wider equine veterinary community, so please contribute. Every case, technique, test and interpretation are different, no matter how experienced we are or how routine the case is, so there is always something for us to learn from each other.

Take photos, dig out your diaries, get keyboard tapping and share your views with colleagues. You could be $150.00 richer for it!

Please send your clinical reports to the EVP Editor for consideration. Joe is happy chat with you about any articles or ideas you might have. Please contact Joe at evp.editor@gmail.com or on 027 437 3651.

Podiatry Pages is a 7-part series overviewing some commonly seen hoof abnormalities in sport and racehorse practice using case examples demonstrating an approach to their treatment and management. Topics discussed include:

• Approach to the physical examination of the hoof

• Caudal failure and negative palmar/plantar angles

• Contracted heels and other capsular deformities

• Thin soles, weak walls

The previous instalment of Podiatry Pages discussed the aetiology of caudal failure, an extremely common abnormality seen in shod horses. However, a smaller population of horses have hoof capsule deformities that go the opposite direction when shod, developing upright, contracted heels or uneven, “sheared” heels. Though these capsular distortions can be seen in barefoot horses as well, with 8% of feral horses affected1, there is an overrepresentation of these defects amongst the shod population, ranging between 65%-95% depending on study parameters and population of sport horses.2,3,4,5 One theory behind heel contraction is that steel shoes have been shown to limit movement and expansion of the caudal structures of the foot,6,7,8,9 which can reduce circulation to the foot causing atrophy of the digital cushion and frog structures, leading to contraction.10 However, more recent research has demonstrated that, though there is some correlation between shoes and contracted heels, the cause is more multifactorial, incorporating, genetics, environment, bodyweight, conformation, application of farriery, etc.11 Pain can also contribute to development of contracted heels, with 3.3x more horses diagnosed with hoof pain having concurrent heel contraction.12 This is postulated to be caused by toe-first landing or other biomechanical factors reducing pressure to the caudal half of the foot.13

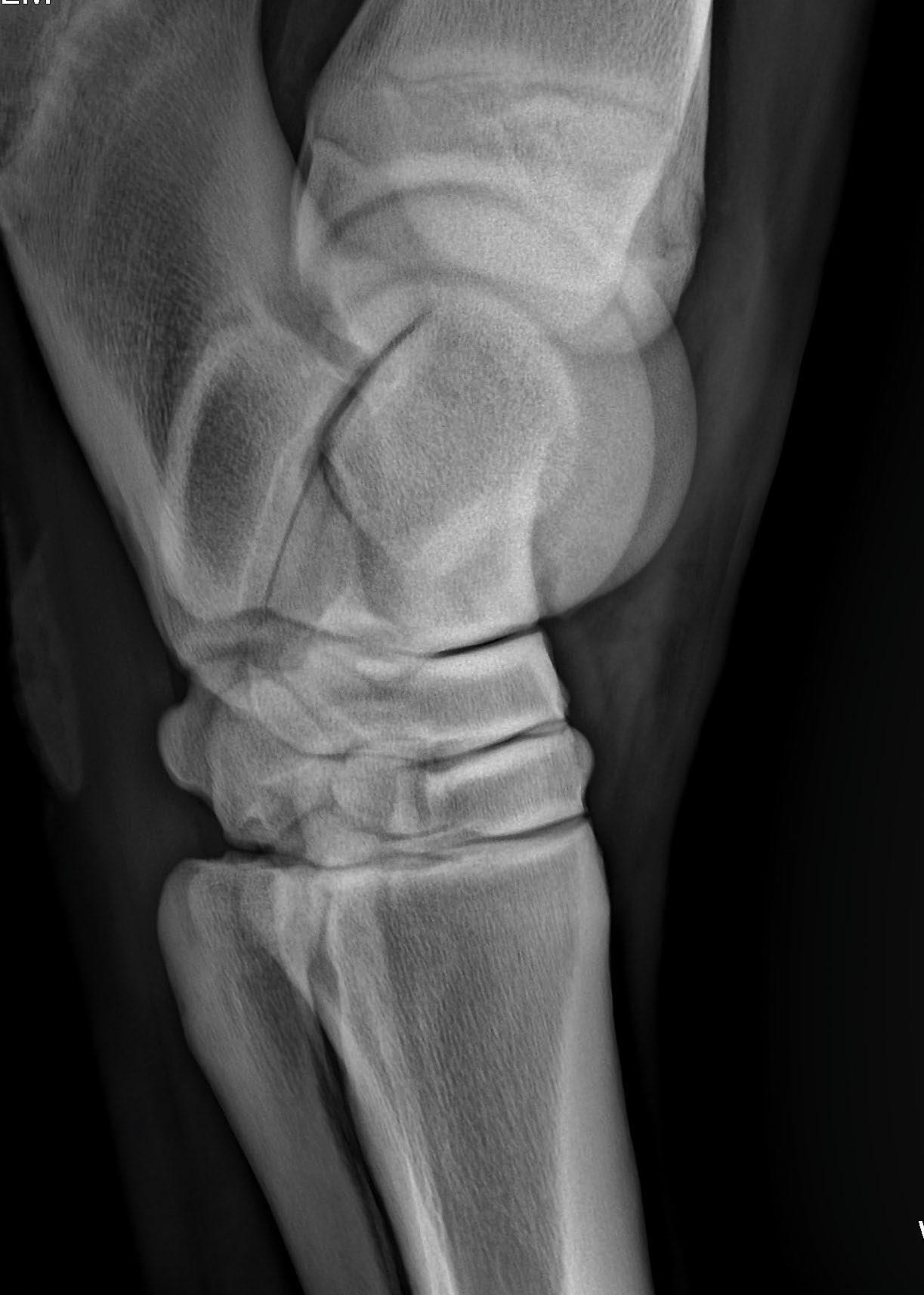

Signalment: 12yo Hanoverian mare training Grand Prix Dressage. Initially 2/5 lame right fore with effusion in both front fetlocks and a bilateral positive response to distal limb flexion, worse on the right fore. Radiographs of both fetlocks were taken which revealed bilateral osteochondral fragments on the sagittal ridge of the third metacarpal bone, visible only on flexed lateral views. The mare had arthroscopic surgery

• High-low syndrome

• Angular limb deformities affecting hoof balance

• New technologies and materials – the future of equine podiatry

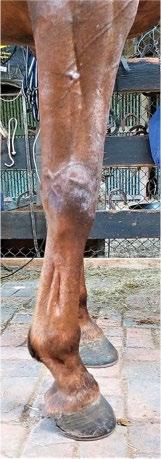

to remove the fragments and was treated with intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells 2 months and 5 months post-operatively. She remained sound during her recovery and rehabilitation programme, however the owner noticed that the mare had gradually become tighter through her forelimbs and over at the knee, especially on the right forelimb (Figure 1).

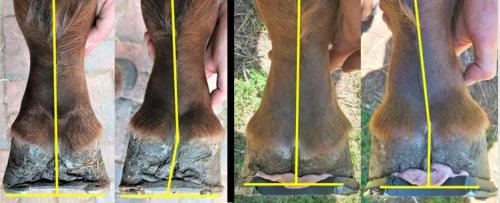

Examination: The mare was examined for the progressive contracture 6 months after surgery. Comprehensive assessment of her conformation revealed a bilateral fetlock varus conformation (worse on the right forelimb), with laterally offset cannons, and some thickening of the lateral aspect of the left carpus (Figure 2). She had upright, contracted hooves, especially on the right fore. There was extreme tension of the antebrachial and pectoral musculature, and the mare was over-at-the-knee slightly on the right forelimb (Figure 1). She had a mild degree of “High-Low Syndrome,” with the left fore being lower in heel height than the right fore, and the right fore was more contracted and mediolaterally imbalanced than the left forelimb. There was no gradable lameness observed and no painful response to flexion of the forelimbs.

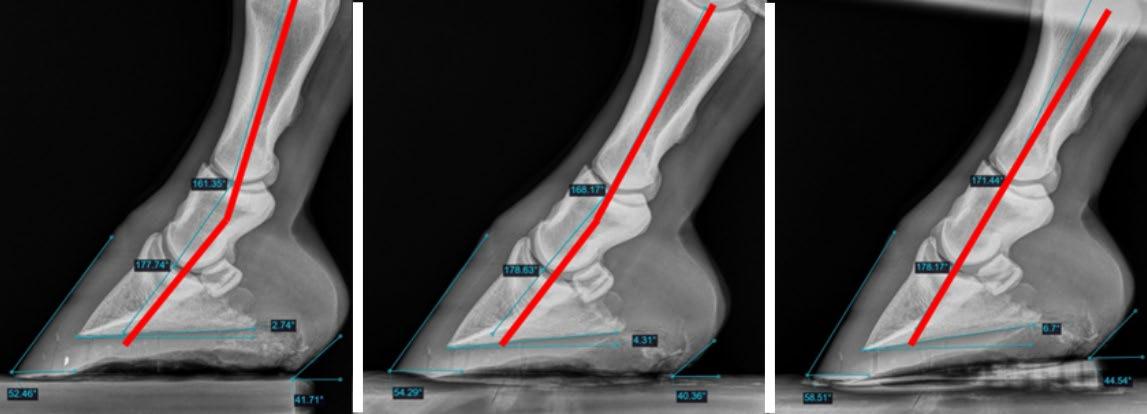

Radiographic examination revealed above average linear bony column alignment of the distal phalanges (P1, P2, P3) with a palmar angle of 3.7o on the left forelimb and 6.4o on the right forelimb. There were no significant mediolateral imbalances radiographically.

Plan: Usually it is preferred to remove the shoes to allow contracted heels to relax down an expand outward over the course of a few months to try to correct the issue. However, the owner wanted to continue progressing through the postsurgical rehabilitation programme and was not open to going barefoot for a short time in this instance because the mare was nearly back in full work. The decision was made to

Figure 1: Mare exhibiting tension through the antebrachial muscles and contracture through the carpus, upright pasterns, and toed-in conformation.

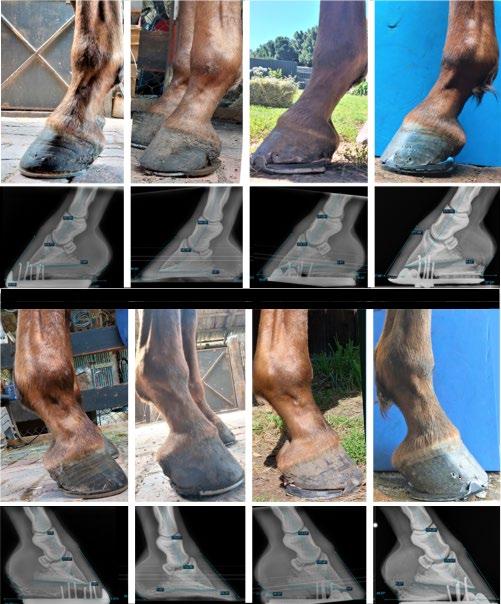

mimic barefoot biomechanics and remove heel restriction as much as possible using a “FlipFlop” pada and an aluminium breakover shoeb cut in half (Figure 3). The mare remained in the “Flip-Flops” for 3 months with no reported issues in lameness or performance observed during this time. Follow-up examination was performed prior to the 3rd set of shoes being placed. The mare’s heels had visibly lowered on both front feet, especially the lower left forelimb. Radiography showed that the mare was now at a zero-degree palmar angle on both front feet. However, physically, her limbs had relaxed and her

Figure 3: Example of the initial shoeing package.

Image: American Farriers Journal.

carpus was fully engaged. The owner, who was very diligent and observant, stated that there was only progress in her movement and demeanour and was pleased with the response, despite the obvious deterioration in palmar angle observed radiographically. There are many factors that may have been at play with this occurring: 1) the original farrier was injured during this time and an apprentice was shoeing the horse, 2) the shoeing changes occurred during a very wet winter which may have contributed to softening of the hoof capsule, 3) anecdotally, I have often observed sound, barefoot horses to have ground-level palmar angles but having wide heel bulbs and the appearance of a healthy frog and digital cushion, so more research into average palmar angles in shod versus unshod horses may be needed in the future to define what truly is “normal.” However, the vast amount of research showing a straight hoof-pastern axis and linear phalangeal alignment being the target biomechanical “ideal” has the most merit to maintaining soundness in performance horses and is still the goal for this horse.

Though there was an over-correction in the heel height, there was improvement in the width and substance of the heel bulbs and digital cushion, as well an in improvement in the angles of the quarters, which improved the imbalance of the right forelimb quite dramatically (Figure 4).

Due to the deterioration in palmar angles, it was necessary to change the shoeing package to a 3-degree frog-support padc to support the heels and allow the palmar angle to return to normal. Photos of the mare were taken with the new shoeing package placed and the relaxation in the forelimbs is visible when compared with the mare’s original posture (Figure 5) even though the internal phalangeal alignment and palmar angle is radiographically similar.

The horse remained in the new shoeing package for 6 months

and 5 shoeing cycles (Figure 6). The owner reported no issues with lameness and emphasized that the mare seemed to be improving month-on-month. A follow-up exam was performed at 6 months. There was improvement in palmar angles on both front feet, with the left forelimb at 2.7o and the right forelimb at 6o. The overall hoof quality had improved, with minimal evidence of horn tubule compression and abnormal growth rings. The right fore had made the most dramatic improvement and was moved to a flat frog-support pad at this stage. The left forelimb was trimmed to a 4-degree palmar angle but still required a degree pad (Figure 6) to restore phalangeal alignment based on this horse’s conformation.

Figures 7 and 8 present sequences of images summarising the transformation process. Given the High-Low syndrome that became more evident as the hoof rehabilitation cycles when on, there are still some further modifications to be made in the future, and perfect symmetry may never be achieved. However, the mare has only showed continued muscular relaxation, comfort, and improvement in performance throughout the process, which hopefully means we are on the right path.

1. Hampson BA, MA de Laat, PC Mills, CC Pollitt (2013). The feral horse foot. Part A: observational study of the effect of environment on the morphometrics of the feet of 100 Australian feral horses. Aust Vet J, 91: 14-22

2. do Canto LS, FD de La Corte, KE Brass, MD Ribeiro (2006). Frequência de problemas de equilíbrio nos cascos de cavalos crioulos em treinamento. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci, 43: 489

3. De Melo UP, RMFW Santiago, RA Barrêto, C et al (2011). Biometry and hoof balance alterations in horses used to vaquejada. Acta Vet Bras, 5: 368-375

4. Maranhão RDPA, MS Palhares U Pereira de Melo, HH Capuano de Rezende, C Ferreira (2007). Avaliação biométrica do equilíbrio podal de eqüídeos de tração no município de Belo Horizonte. Cienc Anim Bras, 8: 297-305

5. Sampaio BFB, CESN Zúccari, MYM Shiroma, et al (2013) Biometric hoof evaluation of athletic horses of show jumping, barrel, long rope and polo modalities.

Rev Bras Saúde Prod Anim, 14: 448-459

6. Brunsting J, M. Dumoulin, M. Oosterlinck, M et al. (2019) Can the hoof be shod without limiting the heel movement? A comparative study between barefoot, shoeing with conventional shoes and a split-toe shoe. Vet J, 246: 7-11

7. Roepstorff L, C. Johnston, S. Drevemo. (2001). In vivo and in vitro heel expansion in relation to shoeing and frog pressure. Equine Vet J, 33: 54-57

8. Colles CM. (1989). The relationship of frog pressure to heel expansion. Equ Vet J, 21: 13-16

9. Yoshihara E, T Takahashi, N Otsuka et al. (2010) Heel movement in horses: comparison between glued and nailed horse shoes at different speeds. Equ Vet J, 42: 431-435

10. Teskey TG. (2005). The unfettered foot: a paradigm change for equine podiatry. J Equ Vet Sci, 25: 77-83

11. Senderska-Płonowska M, P Zielińska, A Żak, T Stefaniak. (2020) Do Metal Shoes Contract Heels? A Retrospective Study on 114 Horses. J Equ Vet Sci, 95:

Figure 8: Upper 2 rows – LF, clinical and radiographs. Lower 2 rows – RF, clinical and radiographs. Left to right clinical and radiographic pairs of images - Day 1 before new shoes; 3 months with Flip-Flops; first caudal support package; after 6 months in caudal support. Notice the health and integrity of the hoof walls (column 4) relative to the original photos (column 1). 103293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2020.103293.

12. Turner TA, C. Stork. (1988). Hoof abnormalities and their relation to lameness. Proc 34th Annu Conv Am Assoc Equ Pract, San Diego, 34: 293-297

13. Baxter GM, T. Stashak, C. Hill (2011) Conformation and movement. Adams & Stashak’s Lameness in Horses. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 73-108

a. Grand Circuit® Flapper Pad - https://grandcircuitproducts.com/ b. Mustad® Equilibrium Shoe - http://www.Mustad.com c. 3DHoofcare® Half Mesh Pad - http://www.3DHoofcare.com

Pearce.patricia@gmail.com

What is your practice area, and how many years have you been doing this?

Panic! Rebecca and Joe want this by tomorrow so instead of being witty and succinct you will get the garbled barebones. I am currently Veterinary Advisor to the NZ Equine Health Association but have a few other equine roles including sitting on the Racing Integrity Board.

Where did you obtain your veterinary degree, and did you take on any post-graduate studies?

I migrated to Massey from small town Gore. I recall standing at the letterbox with my dad with the acceptance letter into the vet course in my hand feeling very relieved, proud, and excited while my poor father looked at me perplexed and asking if I was sure I didn’t want to be an architect? He was a builder so I wonder if he was worried about succession planning and as the youngest in the family I was his last hope. But no, of course I had to be a vet! I obviously also desperately must have wanted to be a wife too as I quickly seduced the local talent and married a classmate before I graduated in 1982 - but only after a year off to taste the delights of North America.

Why did you choose this area of practice?

My eventual areas of practise were not what I had planned at all. Most vets employed in rural NZ in 1982 did everything. Two jobs were on offer in rural Rangitikei in 1981, Tim my super talented spouse got one of them, but I seemingly wasn’t a contender for the other. The opposition Vet Club was sure Tim would poach their clients if I worked for them, which if analysed probably meant they thought I’d be bloody useless and he was supa-dupa!

As a fresh graduate I took a job working for MAF at the Borthwicks Meat works in Feilding fully intending for it to be short term. I didn’t think it was a good plan to work in the same business as Tim, and after a year or two my confidence that I could easily swap into equine practice waned, so I carried on working for MAF. The plus was I got better work life balance and got home in the daylight and could ride lots of horses. Soon Tim and I were spending all our spare time riding, competing, secretarying in equestrian events and selecting and bringing on showjumpers; this didn’t change for 40 years. By the 1990s I had switched to becoming a “field vet” working in the Wanganui area and that work was varied and way more interesting. It included involvement in quarantine programmes for new sheep and goat breeds, joining flights of horses into NZ, and participation in national disease eradication programmes which included curly

challenges such as attempting to allay community concern about aerial 1080 drops. It was in this job that I became heavily involved in Animal Welfare promotion and enforcement. I was a regional animal welfare coordinator and in this role worked with David Bayvel, a canny capable Scot, who joined the long list of wonderful mentors I benefited from. In that very long list I have to name Peter Jacques and Brian Goulden - and there are another 100 - but in the interests of brevity I will leave you to guess. In fact, if you are still reading this there is a very good chance that you might be one of them.

Any bumps and hurdles along the way to get here?

I don’t know if children are bumps in one’s career, but I found it really difficult working full time and trying to raise humans, in spite of having a pretty strong contributor as a spouse. I sometimes reflected that believing I could work and raise unscrewed up children was a big con. That thought is probably reinforced largely from the loss of our son Cameron who committed suicide when he was 19 years old. I still want to cry as I write that. Juggling work and family is a big job and if you don’t change your expectations, like me, then you can get sucked into thinking that anything that goes wrong is because you did neither very well. Alex my daughter blows that theory to bits though as she is smart, pragmatic, sane and of course beautiful. Life is full of bumps and I don’t have the answers but family and friends are very handy to pull you out of the mud and should the task be too monumental for them then time softens most things.

Outline the data and knowledge sources that are most useful to staying current in your areas of practice.

While working at the meat works, I started a Diploma in Meat Technology and didn’t finish. I also didn’t sit my membership exams in Epidemiology after wading through the course as I spent the day in labour - about as much fun! I did however enjoy and complete the first round of membership exams in animal welfare with the Australian & New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists a few years later. I continued to

be immersed in Animal Welfare stuff, helping develop the training material for MAF Animal Welfare Inspectors and was assigned to verify that the welfare impacts of the Kaimanawa horse muster were minimised when population management efforts commenced to address the impacts of over 2000 horses on the fragile volcanic plateau at that time. When MAF was restructured I also restructured and moved sideways into Animal Welfare and Biosecurity related auditing then into MAF Emergency Management. During this time I won a Continuing Education award that sponsored my costs to complete a Masters Degree which I chose to do at Victoria Uni in Strategic Studies. This might be seen as a bit left field, but it widened my thinking, slightly improved my writing skills and gave me an introduction into what governance was all about.

All through my working life it was often the ‘spare time’ equine industry-related voluntary roles that gave me most pleasure. In the 90’s I joined the committee of the New Zealand Equine Health Association as the representative for Equestrian Sports. After 10 years on the committee, I took up the Chair role then took up a part time advisory role. This job has grown and grown and is the most diverse, challenging but best fun job I’ve had so far. The role has grown my skills in epidemiology, microbiology, virology, immunology, communications, project management and lots more.

What is the most challenging part of your job?

A lot of my job has demanded doing things I’ve never done before. Getting an equine biosecurity levy gazetted probably would not thrill the average vet as an achievement for example. When I started on it, I had no idea what to do, and only half believed it could be accomplished, but it will be the key that enables the equine sector to manage imminent and likely future disease threats. When one considers that we import more live horses than any other livestock sector, and from countries that have 10 times more diseases than NZ, we must accept that we need to stay invested in a solid risk management strategy. Climate change will not make disease exclusion any easier. Living without disease is one of the most important welfare benefits we can afford our horses, so the unique challenge of this job is describing and advertising the benefit of not having something!

Working alone would have been a lot more challenging without the support of a great committee. The current Chair, Ivan Bridge is a really dedicated, hardworking, generous boss, and when I’ve hit the wall on what to do next he has always been available and seemingly free to chat.

What advice would you give to someone thinking of following your line of practice?

I have a fantastic job and luckily NZEHA is growing. Should our BVSc [Massey] programme include substantial species or discipline specialization, or should that be mainly left to post-graduate training periods?

Who as a student has a clear view of where their career will

take them over the next 40 plus years? There is so much that could be jam packed into a degree, but I am so fortunate that I was not sent down a narrow track of specialisation based on an uninformed decision I had to make at aged 20!

What are your passions outside of work?

As well as attempting to stay on top of horses I enjoy farming, especially on the sunny days when the troughs are working, the fences are all tight and well stapled, and it’s not hailing during lambing. I am slightly addicted to buying plants and I quite like weeding. I have an e-bike and a set of skis that I will dust off soon.

Share your best practice tip

GSI. (Get Someone In…usually Tim) Give us a Tweet on Brexit, Trump, Putin… or anyone/thing else you like. Wordle is the new Tweet

Sporting event/concert you travel back in time for: Pink Floyd’s The Wall concert in Berlin

Last memorable meal: Tim’s fish pie

Best-ever or best-tentative dinner party guests: The book club ladies

First-ever concert: Monty Python at Hollywood Bowl

Favourite ever album/band: Queen

Finish the sentence: no woman/man should ever wear… Holey socks Beer or wine/Stones or Beatles: Both, I’m a very rounded person! Hazy beer and cardinay Like the Stones’ endurance and energy, but the Beatles lyrics What was the last lie you told? “Yes, I saw you pass me on the road”

Most interesting surgery you have done: Does a post-mortem count? Best self-defence tip: Watch carefully

Person(s) who influenced you most in your life: This list is very long…. some are mentioned in the epistle above

Best life lesson/life motto: “Failure is part of the process; you just have to learn to pick yourself back up”. Michelle Obama

Final personal story/comments I think I’ve gone on long enough…..

All you need to do is write a clinical report that is published in the EVP, and your contribution may be eligible for one of several prizes of $150.00 that the EVP has available each year. The EVP Editorial Group wish to promote the sharing of your interesting cases and practice tips with the wider equine veterinary community, so please contribute. Every case, technique, test and interpretation are different, no matter how experienced we are or how routine the case is, so there is always something for us to learn from each other.

Take photos, dig out your diaries, get keyboard tapping and share your views with colleagues. You could be $150.00 richer for it!

Please send your clinical reports to the EVP Editor for consideration. Joe is happy chat with you about any articles or ideas you might have.

Please contact Joe at evp.editor@gmail.com or on 027 437 3651.

The US Jockey Club has released its 2021 Edition of the Fact Book.

The online Fact Book is a statistical and informational guide to Thoroughbred breeding, racing and auction sales in North America that also features a directory of international organizations including NZ Thoroughbred Racing.

Of some note is that import/export and sales trends have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. When compared to 2019, the 2020 imports decreased 23%, exports decreased 36%, and mean yearling price decreased 20%.

The Brian Goulden Perpetual Trophy will be awarded annually and presented at the Annual Dinner of the NZEVA conference.

This annual prestigious prize is awarded to members or past members of the NZEVA who have shown leadership, enterprise, contribution to knowledge or education, and have made significant contributions to the equine veterinary profession in New Zealand.

Please send name, address and qualifications of your nominee, along with any supporting information, whom the nominator considers merits the award. This can include curriculum vitae, letters of support and documentation of achievements etc.

Send all details AT ANT TIME to nzevasecretary@gmail.com.

Brendon Bell NZEVA President nzevapresident@gmail.com

AUSTIN TX. USA 23-25 JUNE 2022

Here we offer selected, curated clinical extracts from papers and abstracts presented at the Hybrid ACVIM Forum, 2022.

Environment: The first approach is to use feedstuff and bedding that generate low dust levels. The second approach is to increase removal of airborne particles by improving ventilation in the barn or stall. The ideal environment for horses with severe asthma (RAO) is pasture. If the horse cannot be kept on pasture, ventilation in the barn and stall, the type of bedding, feedstuff, and general management should be scrutinized to minimize allergen exposure. Most horses improve clinically 1 to 2 weeks after being turned outside on pasture. Medical therapy helps speed up recovery. Horses with summer pasture-associated asthma are generally affected in late summer and the recommended environment for these horses during the summer is low-dust indoor housing. Some horses suffer both from classic and summer pasture-associated asthma.

Antibiotics: A large proportion of racehorses suspected of respiratory disease because of poor performance, cough, or nasal discharge are treated with antimicrobials mostly without evidence of bacterial infection. Available data shows no association between response to treatment and antimicrobial medication used. Only a proportion of racehorses diagnosed with mild asthma respond in part to a single course of antibiotic therapy.

Systemic Corticosteroids: These are potent inflammation inhibitors proven to be effective for the treatment of severe asthma (Table 1). Beware of risk of complications such as laminitis. Maximal benefit may take a week.

Inhaled Corticosteroids: Recommended dosages for the off-label inhaled corticosteroids are summarized in Table 2. The latest and only inhaled corticosteroid approved for the treatment of severe equine asthma is ciclesonide (Aservo® Equihaler®; Boehringer Ingelheim). Improved clinical signs, decreased airway hyperresponsiveness, and reduced pulmonary inflammation are usually detectable within 2 weeks of therapy. Therapy with inhaled corticosteroids results in faster improvement of clinical signs and lung function as compared to environmental management alone.

Corticosteroids

Dexamethasone 0.04–0.1 mg/kg IV or IM 0.08–0.165 mg/kg PO Once per day or every 2 days

Dexamethasone 21-isonicotinate 0.04 mg/kg IM Every third day

Isoflupredone acetate 0.03 mg/kg IM Once per day

Prednisolone 1.1–2.2 mg/kg PO Once per day

Triamcinolone acetonide 0.04–0.09 mg/kg IM No less than 3-month interval

Bronchodilators

Aminophylline 5–12 mg/kg IV 6 mg/kg PO Every 12 hours

Clenbuterol 0.8–3.2 µg/kg PO Every 12 hours Furosemide 0.5–1 mg/kg IV Every 8–12 hours

Glycopyrrolate 0.0022–0.007 mg/kg IV Once Isoproterenol 0.1–0.2 mg/kg IV Once N-butyl scopolammonium 0.3 mg/kg IV Once

Pentoxifylline 35 mg/kg PO Every 12 hours Theophylline 5–10 mg/kg PO Every 12 hours

Systemic Bronchodilators: These should not be used alone for extended periods of time because they have no anti-inflammatory properties and do not reduce airway hyperresponsiveness. Some bronchodilators (e.g., beta-2 agonists) induce airway receptor downregulation that renders the drug less effective, prevented by combined use of beta2 agonists with corticosteroids. Use of the three classes of bronchodilators available are summarised in Table 1. Oral absorption tends to be very variable and effects short lived.

Beclomethasone 80 µg HF EADDa 1–3 µg/kg, q 12 h

Ciclesonide 343 µg Soft Mist™ Aservo EquiHalerc 2744 µg q 12 h for 5 days; 4116 µg q 24 h for 5 days

Fluticasone 220 µg HFA AeroMaskb 2–6 µg/kg, q 12 h

Albuterol 120 µg HFA EADD 360–720 µg 1–3 h AeroHippusb/Equine Halerc 1–2 µg/kg

Ipratropium

20 µg 200 µg/capsule 0.02% solution for nebulization

CFC# DPI 2.5-ml vial

AeroMaskb EquiPoudred Ultrasonic nebulizer

0.2–0.4 µg/kg 2–3 µg/kg 2–3 µg/kg 4–6 h

Fenoterol 200 µg CFC# AeroMaskb 1–2 mg 4–6 h

Pirbuterol 200 µg CFC# EADD 600 µg 1 h

Salmeterol 50 µg CFC# AeroMaskb 210 µg 6–8 h

Cromones

Cromolyn sodium 0.02% solution for nebulization 2-ml vials Jet nebulizer Ultrasonic nebulizer 200 mg q 12 h 80 mg q 24 h

Inhaled Bronchodilators: Main classes of inhaled bronchodilators that have been used in the horse are beta-2 agonist and anticholinergic drugs (Table 2). The effects of anticholinergic drugs on airway smooth muscle are additive to beta-2 agonists.

Other Therapies: Supplementation of diet with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in combination with reducing exposure to dust results in improved clinical signs and lung function, as well as reduced airway inflammation. Sodium cromoglycate (cromolyn) improves clinical signs and decreases bronchial hyperresponsiveness when administered to horses with mild asthma only in cases characterized by a high mast cell count in BAL fluid.

NOTE: The diagnosis of mild asthma in racehorses is based solely on BAL fluid cytology so anything irritating the airway may cloud the diagnosis in those responding to antibiotics.

involuntary muscle contractions and stiffness that leads to a stiff gait and can progress to an inability to stand, seizures, fevers, and tachycardia. Parathyroid hormone concentrations are low or ‘inappropriately’ normal (i.e., they should be high due to the hypocalcaemia). A definitive diagnosis can be made via genetic testing. Calcium supplementation may suppress seizures in affected foals, but there is no cure for EFIH.

Equine Juvenile Degenerative Axonopathy (EJDA): In 2020, six related Quarter Horse (QH) foals (4 female, 2 male) were identified that had developed an acute onset of severe ataxia at 1–4 weeks of age. Clinicopathologic findings will be discussed, along with necropsy results and an up-to-date genetic analysis, which suggests an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance to this newly described disease.

Finno

UC Davis. CA, USA

Equine Familial Isolated Hypoparathyroidism (EFIH) is an autosomal recessive, fatal condition of TB foals up to 35 days of age. Affected foals suffer from hypocalcaemia, resulting in

Toby L. Pinn-Woodcock et al. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Healthy horses from 9 locations in mainland USA were classified by latitude zone: northern (n=36), central (n=85), and southern (n=33), and plasma ACTH was measured once

to twice monthly. The ACTH upper reference limits were higher during July–November [equivalent to Jan–May in NZ] compared to December–June [June–Dec in NZ] in all latitude zones (p<0.0001), but no significant differences were detected between latitude zones. Horses >15 years of age exhibited higher ACTH upper reference limits during the late summer/fall compared to younger horses (p<0.0001). The results indicate that plasma ACTH concentrations are elevated in healthy horses during late summer/autumn throughout the USA and age is likely to be an important factor when interpreting ACTH results during late summer/autumn months.

Forty-three of 135 horses (32%) were positive on faecal PCR for ECoV, and 17 horses (13%) developed clinical signs. Colic occurred in 46% of affected animals. Three horses had small colon impactions, two of which required surgical intervention. Significant risk factors for having positive PCR results included presence of clinical signs (OR 56, 95% CI 8.3–594.6), being primarily stalled (OR 167.1, 95% CI 26.4–1719.0), housing next to a positive horse (OR 7.5, 95% CI 3.1–19.0), being in work (OR 26.9, 95% CI 4.573–281.9), being fed a ration of hay vs. ad libitum hay (OR 418, 95% CI 36.8–4438.0), being fed alfalfa hay (OR 418, 95% CI 36.8–4438.0) and levothyroxine supplementation (OR 7, 95% CI 2.7–18.7).

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) that occurs in horses of both sexes and different breeds, is a rare, lateonset immunologic disorder of B-cell depletion and/or dysfunction with resultant inadequate antibody production. Clinical signs appear at an average age of 12 years (range 2-27 years). Hypogammaglobulinemia leads to recurrent infections and fevers, with the most common presentations being pneumonia, sinusitis, meningitis, ataxia, peritonitis, gingivitis, sinusitis, hepatitis, diarrhoea, GI parasitism, uveitis, conjunctivitis, and/or skin lesions. There is persistently low serum IgG concentration (<800 mg/dL) and serum IgM concentrations are markedly reduced (<25 mg/dL) in most patients, suggesting the inability to elaborate primary immune response. Serum IgA and IgE concentrations may also be very low. Neutrophilia and hyperfibrinogenaemia are present during active infections, but persistent lymphopenia (<1,200 cells/µL) is common. An important differential diagnosis is lymphoma since some forms of this type of cancer may alter lymphocyte distribution and function, including B-cell lymphopoenia and hypogammaglobulinaemia. Management of horses with immunodeficiency can be difficult and impacts on the decision of euthanasia, with only rare cases being managed for a few years when serum IgG concentration remains above 600 mg/dL.

Rod Bagley

Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA