10 minute read

Better Business – Rethinking waste tyres

Story by Gavin Myers

TAKING WASTE TYRES TO THE NEXT LEVEL

Waste tyres have always left a black mark on the recycling industry. Rubber itself never disappears; no matter what you do with it, it will always languish in a landfill at the end of its life. That’s unless you can keep using it, over and over, in the manufacture of new tyres.

REVYRE is a Kiwi start-up with huge ambition – and huge potential. The company was started three years ago by CEO Shaun Zukor, who recognised the need to do more around tyre recycling in New Zealand. Zukor knew that to make a true impact on the 90,000 tonnes of tyre waste generated each year in New Zealand, and to make it an economically sustainable endeavour, he’d have to look beyond traditional mechanical tyre shredding that produces an impure crumb rubber of little value.

Zukor’s research led him to a Canadian company called Tyromer that has developed a devulcanisation process that turns the tyre rubber back into its raw state (known as Tire-Derived Polymer or TDP). Zukor was so convinced by what he saw, he put down a deposit there and then for the licences to operate the technology in New Zealand, Australia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

The extent of the problem

Zukor explains that a tyre is made up of approximately 30% carbon black, 30% natural rubber, 30% synthetic rubber and other filler components. Natural rubber plays a large and important part in the construction of a tyre due to its good wear durability, flexiblilty and high tensile strength.

Tony Hannon, chairman of InfraCo Limited, the holding company of REVYRE, explains that globally, 2 billion tyres (50 to 80 million tonnes) go to waste per year. “Tyres account for half of the total global rubber utilisation, which means that, of that 50 to 80 million tonnes of tyre waste, about 14 million tonnes of natural rubber is discarded per year. Natural rubber is a resource in high demand, and so the sustainability of one-third of tyre componentry globally is under threat.”

Currently, in New Zealand, the only legislation around waste tyres concerns the stockpiling of tyres in different regions. The tyres either get dumped illegally, are processed into shreds for incineration domestically, or are baled and sent offshore to be burnt in kilns. Things are changing, though, and soon waste tyres will need to be kept and processed locally. “Tyres are a great resource if processed correctly,” says Zukor.

The legislative environment is changing around the world, too. Australia has banned the exportation of baled tyres to Asia, while India – one of the world’s largest markets for waste tyres – is in the process of banning their importation. In Chile, 20% of tyres have to be recycled sustainably by 2025, and in Canada, all tyres are recycled.

“There needs to be a massive mindset change and mandatory regulation around the disposal and use of devulcanised material,” comments Hannon.

The detail is in devulcanisation

When a tyre is sent to waste, only 20% of it has

been physically used and worn down. That means a typical truck tyre is 80-odd kilogrammes of percieved waste material when it is scrapped. “Multiply that by 22 to 32 tyres per truck … it’s insane,” says Hannon. This means there’s a lot of waste material to put back into the system.

Zukor explains that devulcanisation is a standalone topic compared to recycling and reclamation. “It takes rubber back to its raw state before it was vulcanised. That’s always been the holy grail around any type of tyrerecycling operation.” While at its core, the process is about recycling – taking a waste product and reusing it – what it really means is that REVYRE is a polymer rubber producer. This is important because, while crumb rubber is still a vulcanised material with limited future use, TDP remains a high-quality highdemand material.

The process is surprisingly simple. The first stage is collecting the feedstock, for which the largest commercial tyres are preferred – anything from truck tyres to 63-inch, 5.7-tonne mining tyres. Passenger tyres are not suitable for TDP production as they constitute a higher percentage of synthetics. “We’re able to deal with a segment of the market that historically has been very difficult to deal with. The larger tyres are extremely difficult to dispose of,” says Zukor.

Breaking down the tyres starts with cutting out the sidewall and then blasting the rubber with high-pressure water, leaving a clean steel carcass. Steel constitutes 25% of a tyre, is high-tensile, and gets sold on as grade1 steel. Meanwhile, the high-pressure water system (supplied by RubberJet) partially devulcanises the rubber (up to 66%) because of how the water strikes the polymer and breaks the crosslinks of sulphur.

The rubber then goes through a drying and classification process. At this stage, it’s a powder-type form, less than 4mm in size, which is then fed into a bulk hopper system which in turn feeds to a twin extruder. The rubber is pneumatically fed at rates of 1250kg per hour and put under high pressure, using inert CO2 (at 1kg per tonne) as a catalyst to break the sulphur bonds for the further devulcanisation of the material. It then comes out as TDP in any form the customer wants.

“Whatever you put into the process, you get out in TDP. The process does not thermally degrade any of the polymers or chemistry in the rubber; the compound’s integrity stays intact. That’s the beauty of it,” says Zukor.

This is important because tier 1 and lower-tier tyre manufacturers are fastidious about what they put into their tyres. Zukor says Tyromer in Canada has been doing tests over the last five years with tier 1 producers and holds accreditations through some of them, while participating in ongoing testing with others. “There has been no negative kickback from any of them around the use of TDP in their tyres,” he says.

Rolling forward

Zukor says that while crumb powders can and do go back into the manufacturing of new tyres or retreads, it is only at 5-8% as a filler. Because of devulcanisation, TDP can be added into new tyres in quantities of more than 20%, creating a lesser need for raw materials. “All tyres should be mandated by regulations to have at least 10% of TDP in them. India for example mandates the blending of 20% agri-derived ethanol in petrol, slowing down the need for oil imports. There is no reason the tyre industry cannot follow suit,” Zukor suggests.

“The process is simple, straightforward, proven and clean,” adds Hannon.

Currently, Tyromer has two plants operational in Canada and another commissioned. The business, through partners, also has one plant in China and another commissioned in The Netherlands. From REVYRE’s perspective, the company is advanced in its developmental process and has identified a site in New Zealand to set up local processing. In Australia, it has partnered with Energy Estate and identified the first site.

In the meantime, say Zukor and Hannon, truckies need to be aware of what happens to their waste tyres and ask questions about where they are going and whether they’re being disposed of responsibly. “They need to ask their suppliers those hard questions,” says Zukor.

“Trucking is front and centre for this in New Zealand; it is such an important part of our logistics chain. Every trucking company is a consumer of tyres, and their clients will want to know what they are doing sustainably in their logistics network. Our aim is to have our truckies understand the huge role they can play in telling the story of sustainability. They drive on 22+ tyres every day,” Hannon concludes.

A glimpse into the TDP extraction process. Photo: REVYRE

INFORMING DECISION-MAKING IN THE ROAD TRANSPORT INDUSTRY

http://irtenz.org.nz/about-irtenz

GETTING THE DRIVE TO THE WHEELS

In the early days of motorised trucking, it was common for the power produced by the engine and transmission arrangement to be sent to the rear drive wheels by chain. It did not take long, however, before this design was replaced by what we have now, a driveshaft connected to the output shaft of the gearbox and to a rear-mounted differential that turns the drive through 90° and transmits the power through the axle shafts to the wheels.

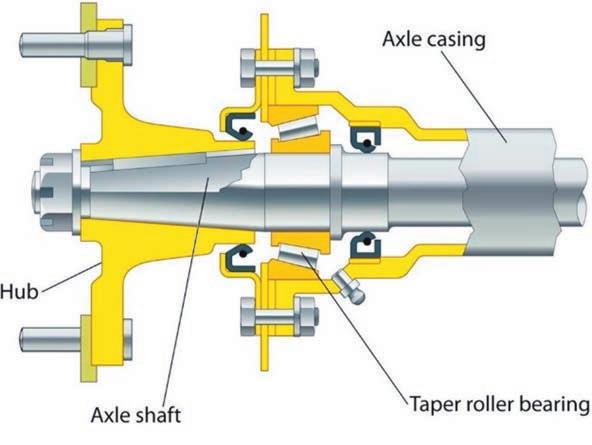

There are three common designs of axle shafts or half shafts, as they are sometimes called. Each is classified by the way they are mounted within the axle casing (housing) and the work they do.

Contribution for IRTENZ by Russell Walsh (Life Member IRTENZ) Images from Blogmech

Semi-floating axle

In this design the outer end of the axle shaft passes through a bearing that is inside the axle housing. The weight of the vehicle is carried by the axle shaft through the bearing. A semi-floating axle must be strong enough to withstand the: • Torque produced by the engine and transmitted to the driving wheels • Retarding forces from the wheels when the brakes are applied • Side thrust imposed during cornering.

The wheels are attached to a hub fitted to the outer end of the axle shaft. This hub is tapered and fitted with a keyway to prevent the axle spinning inside the hub.

SEMI-FLOATING AXLE

THREE-QUARTER FLOATING AXLE

Three-quarter floating axle

Similar in design to the semi-floating axle except the weight of the vehicle is carried through the bearing to the axle housing.

A three-quarter floating axle shaft does not carry any weight of the vehicle but must still be strong enough to withstand the: • Torque produced by the engine • Braking forces • Side thrust imposed when the vehicle is cornering.

As shown in this diagram, the hub bearings used may be either single or double race.

Fully floating axles

The most common axle design used on trucks. In this design the entire weight of the vehicle, side thrust, and breaking forces are taken on the axle housing. The only force that is carried by the axle shaft is the torque produced by the engine and used to move the vehicle. The axle shaft passes through the wheel hub and is flanged so it can be bolted to the outside of the hub. An advantage of this design over semi- and threequarter-floating designs is that the axle shaft can be removed without lifting the vehicle off the ground and removing the wheels and hub, allowing the wheels to effectively freewheel once the brakes are released. This can help if the vehicle must be moved to avoid damaging the differential, driveshaft, or gearbox.

If the vehicle has a Carden shaft parking brake fitted, removing one or more axle shafts will leave the vehicle without an effective parking brake. If the vehicle is stationary, and on a slope, when an axle is removed the vehicle can roll forward or backward so the wheels must be chocked first before the axle(s) are removed.

What happens if an axle shaft breaks? In a semi- or three-quarter floating design, if an axle shaft breaks, the wheel attached to it can fall off. This cannot happen in a fully floating design.

No wonder it’s the world’s favourite forklift. No wonder it’s the world’s No wonder it’s the world’s favourite forklift.

Our 100 year history proves that when you do everything with heart, nothing is too heavy. Our 100 year history proves that when you do everything with heart, nothing is too heavy.

Mitsubishi from Centra, moving Mitsubishi from Centra, moving New Zealand forward. New Zealand forward.