10 minute read

Diagnosing deadly disease

by VetScript

1

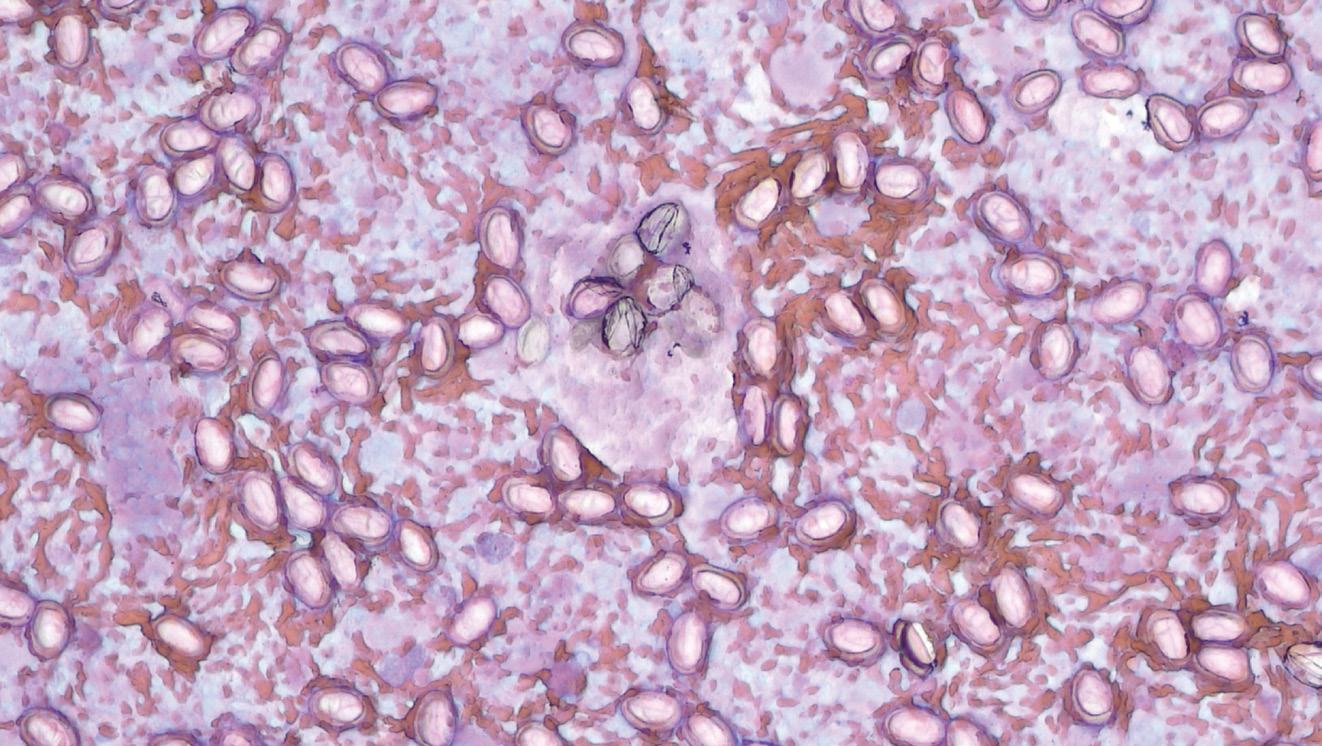

FIGURE 1:Leishman’s stained (A) and Diff-Quik stained and higher magnification (B) hepatic impression smears show a variable number of oval, clear, coccidian oocysts with refractile walls.

Advertisement

A

B

A protozoan problem

Pathologist Lisa Schmidt, from SVS Laboratories, discusses a case of hepatic coccidiosis in a rabbit.

A 10-WEEK-OLD WEANLING rabbit who weighed 380g (half that of its littermates) presented to the lab. The day prior to their death the kit had appeared normal, but 24 hours later they were lethargic and unable to stand. Despite supportive care, the kit died.

NECROPSY

On necropsy the rabbit was thin, lacked body fat reserves (subcutaneous and intra-abdominal) and had a slight pot belly. The liver had a few scattered round, yellow to pearl grey, spherical nodules up to 3mm3.

CYTOLOGY

Impression smears were made of the liver nodules. They showed a variable number of coccidial oocysts (Figure 1) and were supportive of hepatic coccidiosis. For tips on making impression smears, see box.

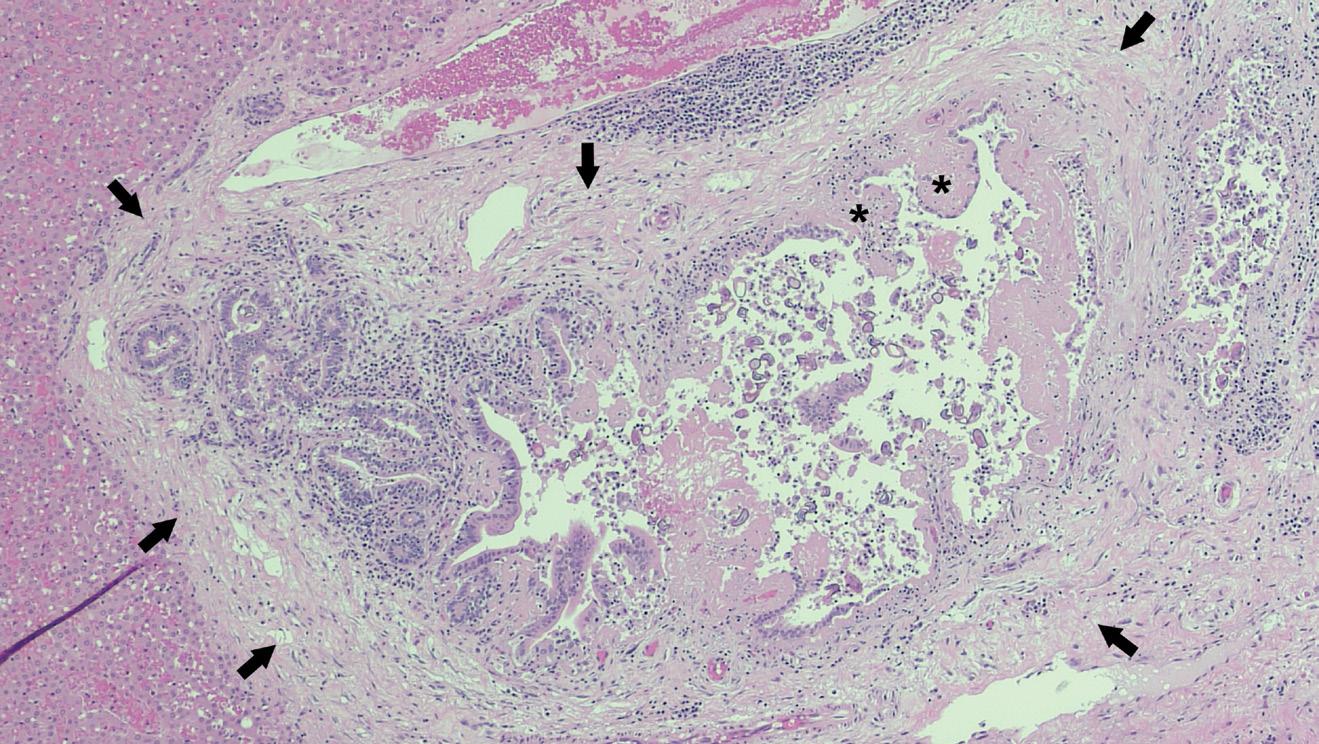

HISTOPATHOLOGY

The bile ducts were dilated with papillary epithelial hyperplasia and periportal fibrosis and inflammation (Figure 2). Coccidial oocysts were seen in the lumina of affected degenerate ducts. A diagnosis of hepatic coccidiosis was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Typically, coccidiosis is a disease of intensively managed animals, especially young, naïve animals who can develop high parasite burdens (Uzal et al., 2016). In rabbits, Eimeria stiedae is one of the most common causes of clinical coccidiosis. Unlike most coccidial infections, Eimeria stiedae preferentially infects the biliary epithelium (Barthold et al., 2016). Naïve rabbits are often infected by ingesting sporocysts (sporulated oocysts) found in the environment of contaminated premises, where they can remain viable for several months, and on fomites. Once ingested, sporozoites invade the duodenum and migrate rapidly to the bile duct epithelial cells via lymphatic and haematogenous routes. Coccidial reproduction begins once organisms are in the bile duct epithelial cells. The prepatent period is 15–18 days and infected rabbits can shed oocysts in the faeces for seven weeks or more (Baker, 1998; Barthold et al., 2016; Uzal et al., 2016). While liver nodules in this case were only 3mm3, they have been reported to be as large as 3cm in diameter in the literature.

Other gross findings that may be seen in affected rabbits include dark-brown to green soiling around the perineum due to diarrhoea, ascites, hepatomegaly and a thickened gall bladder with viscous, green bile and inspissated material (debris) (Barthold et al., 2016).

In this case, the kit showed clinical signs consistent with hepatic coccidiosis. The typical clinical findings are summarised in Table 1. While a serum sample was unavailable for analysis in this case, clinical pathology abnormalities associated with liver

TIPS FOR MAKING IMPRESSION SMEARS FROM TISSUES

STEP 1. Blot the cut surface of the tissue with gauze or paper towel to remove surface blood and serum, until almost dry.

STEP 2. Lightly tap the dried surface onto a dry slide. The tissue can be touched multiple times on the same slide in different locations.

STEP 3. Allow the slide to air dry before staining.

If you have a core biopsy, the tissue can be rolled across a piece of paper towel prior to being gently rolled across a glass slide.

A

disease can be seen. The clinical presentation is described in Table 1.

A definitive diagnosis of hepatic coccidiosis due to Eimeria stiedae is made by demonstrating oocysts in the bile ducts on histopathology (Barthold et al., 2016). In chronic lesions, organisms may be sparse to absent in bile ducts with prominent periportal fibrosis. In this case, postmortem exam findings and cytology were highly suggestive of hepatic coccidiosis. Faecal flotation could also be used to add support to a diagnosis of coccidiosis. In this case, the kit had 4+ coccidia and 700 eggs per gram of strongyle nematodes.

B

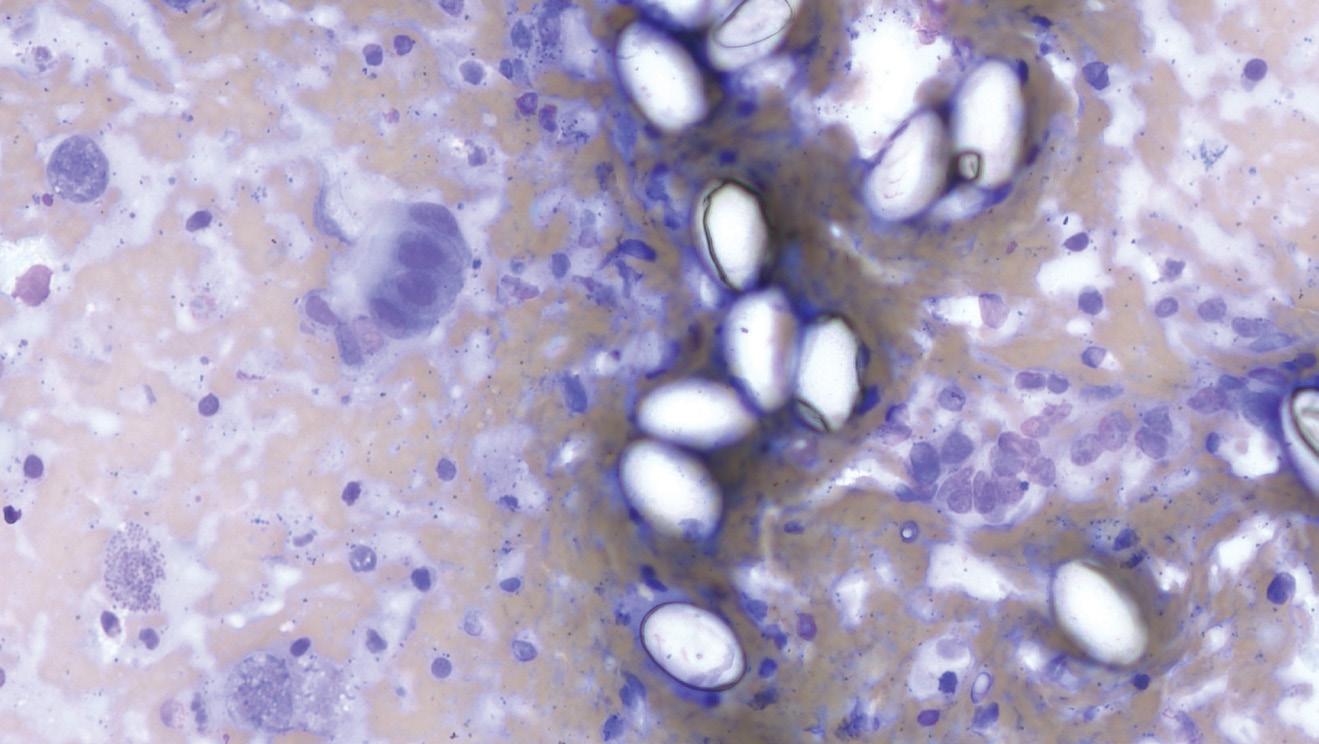

FIGURE 2:(A) Low magnification showing periportal fibrosis (arrow) and papillary epithelial hyperplasia (*). (B) Higher magnification showing a few intra-ductal coccidia oocytes (arrowhead).

TABLE 1: Clinical presentation of hepatic coccidiosis

Typical age

Clinical signs

Serum chemistry

Weanling rabbits

Anorexia Weight loss or poor weight gains ± Distended abdomen (due to an enlarged liver and/or ascites) ± Diarrhoea ± Icterus

Elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) Hyperbilirubinaemia ± Hypoglycaemia ± Hyperlipaemia ± Hypoalbuminaemia ± Hypergammaglobulinaemia

2

SUMMARY

Eimeria stiedae is an important cause of mortality in weanling rabbits, and clinical signs of infection vary with the severity of infection. In mild cases rabbits may have growth retardation. In heavily infected cases rabbits may show signs related to hepatic pathology including dullness, anorexia and debilitation, and/or diarrhoea and/or constipation. Hepatomegaly, ascites and icterus are also reported.

REFERENCES:

Baker DG. Natural pathogens of laboratory mice, rats, and rabbits and their effects on research. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 11(2), 231–66, 1998

Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 4th Edtn. Pp 297–300. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, Iowa, USA, 2016

Uzal FA, Platter BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG (ed). Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals Vol 2. 6th Edtn. Pp 227–39. Elsevier, St Louis, Missouri, USA, 2016

SOCIAL MEDIA – wellbeing friend or foe?

Marie K Holowaychuk asks, “Is Facebook bad for veterinarians’ mental health?”

FOR YEARS, EXPERTS have questioned whether spending time on social media is helpful or hurtful to mental health. I use social media (LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter) for my business – to stay engaged with followers, share pertinent information and form new connections. I also use a personal Facebook account to stay connected with friends and family around the world. After living in six different cities in Canada and the US for the past 15 years, it’s easier to post updates on social media than it is to connect regularly with individuals.

However, the downsides of social media are becoming more apparent. Scrolling

Marie K Holowaychuk is a Canadian small animal emergency and critical care specialist and certified yoga and meditation teacher, with an invested interest in the health and wellbeing of veterinary professionals. She facilitates wellness workshops, boot camps and retreats for veterinarians, veterinary technicians, students and other veterinary care providers. This column originally appeared in her newsletter. For more information and to sign up to her free newsletter, please visit: www.criticalcarevet.ca. through social media mindlessly can be a major time-suck. I recently installed the app Quality Time on my phone and was disgusted with how many times I had checked my phone or spent time on social media during the day. Having this awareness has helped me pare down my social media usage, or at the very least use my time more efficiently.

Social media use also leads to comparisons, which can cultivate feelings of envy and depression. It’s no secret that most of us save our best pictures and favourite features for our social media posts, while leaving our dull or downtrodden moments hidden away. This gives others the false sense that our lives are amazing or even glamorous! People often say to me, “I’m so jealous of your life and all the travel you get to do” but that’s because they don’t see the hours spent packing, prepping, sitting in airports and spending time alone in hotel rooms. Trust me – it’s not glamorous.

There is more research coming out to explain the positives and pitfalls of social media use, which I hope will guide our decisions on if and how we engage with others online. The 2020 Merck Animal Health Veterinary Wellbeing Survey revealed that veterinarians using social media for more than 30 minutes per day have poorer mental health and wellbeing than those who do not. Other studies investigating social media use among young adults and the general adult population have found conflicting results when it comes to the duration of social media use and mental health. Recent studies have begun to investigate the subtler nuances of how people engage on social media and how that affects their wellbeing.

For example, one study compared active social media use (such as messaging a friend or commenting in a group) to passive social media use, including scrolling through and liking posts (Escobar-Viera et al., 2018). Results from more than 700 adults showed that passive social media use was associated with a 33% increase in depressive symptoms, while active social media use

was associated with a 15% decrease in depressive symptoms. So whether you are sitting and scrolling through posts or reading, commenting and engaging with other users appears to have a big role in the mental health effects.

Rather than try to manage the way in which they use social media, some people have chosen to forego it altogether. Several of my friends and family members have deleted their Facebook accounts to break free from the time-suck/comparison trap of social media, sometimes on the advice of mental health specialists. Studies seem to support this: in Denmark, people who took a week-long break from Facebook had better life satisfaction and positive emotions than those who continued using Facebook. These effects were greater for heavy Facebook users and those who used Facebook passively. Perhaps a social media hiatus (or holiday) is something each of us could consider to improve our mental health.

I am not opposed to social media and am grateful to have it for the professional and personal reasons stated above. However, I do think the ways in which it is used affect its impacts on our mental health and wellbeing. As such, I would urge anyone using Facebook, LinkedIn and other social media to consider the following five strategies: » Share posts that are meaningful (ie, pertinent life updates) rather than random pictures of food or unnecessary rants. » Engage with others by commenting on their posts or sharing posts from which you feel others would benefit. » Send messages to friends and loved ones to maintain connections with

those in distant time zones whom you cannot readily call. » Search for local events to attend in person, and invite others to join you for face-to-face connection time. » Join or create closed groups where you can engage with like-minded individuals in a meaningful way. Finally, if you have not done the exercise of logging the time you spend on your phone or social media, I urge you to become aware of your usage by installing a time-monitoring app such as Quality Time, Offtime or Moment. Awareness is the first step to realising that change is needed to foster health and wellbeing.

REFERENCE: Escobar-Viera CG, Shensa A, Bowman ND, Sidani

JE, Knight J, James EA, Primack BA. Passive and active social media use and depressive symptoms among United States adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 21(7), 437–43, 2018

Order your copy now!

Practical guide for cattle veterinarians

The definitive practical guide for cattle veterinarians, authored by Cathy Thompson BVSc.

“The things I wish someone had told me before I had to learn the hard way”. “I’ve had fun and satisfaction in my career as a large animal vet. This book should make those first few years working with cattle and farmers a bit easier for new grads.” “My aim was to combine the many photos I have taken with some practical tips that aren’t in textbooks.”

“Diseases and conditions found on farm are not always the same as the “classic” case in a textbook.”

New Zealand price* (GST inclusive) Retail (1 copy) NZ$200

*Excludes postage and handling Practical guide for cattle veterinarians (Book order form)

Visit www.nzva.org.nz/cattleguide or complete order form below

Order now Name Delivery address

City, Postcode Email Phone/mobile Purchase order no. No. of copies Total amount ($)

for Practical Guide C A T TLE VETERINARIANS

Over 1000 ph o tos

Case studies and anecd o tes Over 50 common conditions and topics Tips and T echniques from over 30 years o f c a ttle practice

C a thy Thompson B VSc.

01 C A TH Y T HOMP S ON B V S c . | Proudly sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health New Zealand Limited

Method of payment

Invoice to company Payments by cheque or direct deposit to: New Zealand Veterinary Association, Westpac, Lambton Quay 03-0502-0622336-00

Credit card payments accepted: Card type Visa Mastercard “Full of tips and advice from a well-respected New Zealand veterinarian. Cathy’s photo collection is legendary and used to great effect. The book is a practical addition to cattle veterinary textbooks; with years of experience distilled into a useful and easy to read volume.

Card number

Expiry date CVV number I highly recommend this book to veterinary students and recent graduates, especially those interested in working with cattle.”

Cardholder name Jenny Weston Academic Dean of Veterinary Science, Massey University