Climate Change, Loss of Agricultural Output and the MacroEconomy: The Case of Tunisia

Les Papiers de Recherche de l’AFD ont pour but de diffuser rapidement les résultats de travaux en cours. Ils s’adressent principalement aux chercheurs, aux étudiants et au monde académique. Ils couvrent l’ensemble des sujets de travail de l’AFD : analyse économique, théorie économique, analyse des politiques publiques, sciences de l’ingénieur, sociologie, géographie et anthropologie. Une publication dans les Papiers de Recherche de l’AFD n’en exclut aucune autre.

Les opinions exprimées dans ce papier sont celles de son (ses) auteur(s) et ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de l’AFD. Ce document est publié sous l’entière responsabilité de son (ses) auteur(s) ou des institutions partenaires.

AFD Research Papers are intended to rapidly disseminate findings of ongoing work and mainly target researchers, students and the wider academic community. They cover the full range of AFD work, including: economic analysis, economic theory, policy analysis, engineering sciences, sociology, geography and anthropology. AFD Research Papers and other publications are not mutually exclusive.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of AFD. It is therefore published under the sole responsibility of its author(s) or its partner institutions.

Abstract

AUTHOR S

Devrim Yilmaz Agence Française de Développement Paris (France)

Kadir Has University Istanbul (Turquie)

Sawsen Ben-Nasr Institut Tunisien de la Compétitivité et des Etudes Quantitatives Tunis (Tunisie)

Achilleas Mantes Agence Française de Développement Paris (France)

Nihed Ben-Khalifa Laboratory of Economics and Industrial Management (LEGI), Polytechnic School of Tunisia, University of Carthage Tunis (Tunisia)

Issam Daghari Institut National Agronomique de Tunisie Tunis (Tunisie)

Using an empirical, multisectoral, open economy, StockFlow Consistent model, this paper assesses the long-term consequences of a sustained climate-induced decline in agricultural production for the Tunisian economy. Focus is placed on agricultural and processed food production and the feedback loops of balance sheet and liquidity effects on the real economy. The model is empirically calibrated using a range of national accounts, input-output, balance of payments and balance sheet datasets, agricultural projections from crop models and it is simulated for the period 20182050. We show that costs of inaction in the face of declining agricultural production are dire for Tunisia. We find that the economy will face high and rising unemployment and inflation, growing internal and external macroeconomic imbalances and a looming balance of payments crisis, especially if global food inflation remains high in the coming decades. We then simulate two possible adaptation scenarios envisaged by policymakers and show that adaptation investments in water resources, increased water efficiency in production and a public, investment driven big push, can put the economy back on a sustainable path in the long run.

Keywords

We are grateful to Antoine Godin for his valuable comments on earlier drafts of this paper. All errors remain ours.

Original version

English Accepted June 2023

Antoine Godin (AFD)

Devrim Yilmaz (AFD)

Ecological macroeconomics, Climate change, Stock-flow consistent modelling, Open economy macroeconomics

En utilisant un modèle Stock-Flux Cohérent multisectoriel d’une petite économie ouverte, ce document évalue les répercussions à long terme d’une baisse soutenue de la production agricole due au changement climatique sur l’économie tunisienne. L’accentest mis sur la production agricole et agroalimentaire, ainsi que sur les boucles de rétroaction des effets des bilans et de liquidité sur l’économie réelle. Le modèle est calibré empiriquement en utilisant des données provenant de diverses sources telles que la comptabilité nationale, les tableaux entrées-sorties, la balance des paiements et les bilans bancaires. De plus, il intègre des projections agricoles basées sur des modèles de culture et les simulations sont réalisées pour la période allant de 2018 à 2050. Les résultats montrent que les conséquences de l’inaction face au déclin de la production agricole sont désastreuses pour la Tunisie. L’économie sera confrontée à une augmentation croissante du chômage et de l’inflation, ainsi qu’à des déséquilibres macroéconomiques internes et externes de plus en plus importants et une crise imminente de la balance des paiements, en particulier si l’inflation alimentaire mondiale reste élevée dans les décennies à venir. Par la suite, deux scénarios d’adaptation envisagés par les décideurs politiques sont simulés, démontrant que des investissements d’adaptation dans les ressources en eau, une amélioration de l’efficacité de l’utilisation de l’eau dans la production, et une impulsion majeure d’investissement public peuvent remettre l’économie sur une trajectoire de développement durable à long terme.

Macroéconomie écologique, Changement climatique, Modélisation stock-flux cohérent, Macroéconomie en économie ouverte

Facedwithworseningglobalwarmingconditionsandlimitedwaterresourcesthatarealready belowthethresholdofabsolutewaterscarcity(MinistryofAgriculture,WaterResourcesand FisheriesofTunisia,2020),Tunisiafacesmajorchallengesandrisksthatcouldexacerbatethe country’sdifficulteconomicandsocialsituationinthecomingdecades.Risingtemperatures andanincreaseinthefrequencyofextremeweatherevents,coupledwithadecreasein rainfall,areexpectedtoaffectboththequantityandqualityofwaterresources,andthusthe economy,particularlyagriculture.Whilethishighlevelofwaterstresswillrequirehighlevelsof investmentinadaptationandefficiencygainsinwateruse,Tunisia’sfragilemacroeconomic outlookimpliesthatefficientuseofpublicandprivateresourcesisessentialtoachieve asustainablewaterbalancealongsidethecountry’sdevelopmentgoals(UnitedNations ClimateChange,2022).

Inthiscontext,thispaperaimstomodelthemacroeconomicimpactsofclimatechange andtheviabilityoflong-termadaptationpoliciesinTunisia,usingaStock-Flow-Consistent (SFC)economicmodelandcropyieldprojections.ThemodelpresentedbelowisamultisectoralextensionofYilmazandGodin(2020),whodevelopaprototypegrowthmodelfor developingeconomies.SFCmodellinghasrecentlybeenusedtoanalysethephysicaleffects ofclimatechangeonglobalmacro-financialdevelopmentsandmacrodynamicstability (Dafermosetal., 2017, 2018; Bovarietal., 2018)andtheeconomicconsequencesofrapid energytransitionpaths(Jacquesetal.,2023),highlightingitssuitabilityforouranalysis.Our novelapproachsynthesisesamulti-sectorproductionstructurewiththeSFCframework andthecontinuous-timedynamic,macrofoundationsapproachoftheBielefeldschoolof macroeconomics,developedbyP.Flaschel,C.Chiarellaandco-authors,inparticularwith respecttodynamicdisequilibriumprocesses(ChiarellaandFlaschel,2006;Flaschel,2008; Flascheletal.,2008;Charpeetal.,2011;Chiarellaetal.,2012,2013).Wealsopayparticular attentiontotheimportanceofcapitalinflowsforsmallopeneconomies(Frankel,2010;Borio andDisyatat,2015),suchasTunisia,andthechannelsthroughwhichtheyaffectthedomestic economy,includinginternationaltrade(Blecker,2016),liquidity(Kaminskyetal.,1997)and balancesheeteffects(BernankeandGertler, 1995).Foragriculturalyieldprojections,we useFAOprojectionsaswellasprojectionsfromtheAdaptActionproject(Deandreisetal., 2021).

Thepaperisstructuredasfollows:thenextsectionpresentsthemacroeconomicdevelopmentsinTunisiaoverthelasttwodecades.Sectionthreediscussestheimpactofclimate changeonTunisiathroughtemperatureandprecipitationprojections.Sectionfourpresents theimpactofclimatechangeonagricultureandtheconstructionofagriculturalproduction projections.ThemacroeconomicmodelanditscalibrationtotheTunisianeconomyare presentedinthenexttwosections.Sectionsevenpresentsthesimulationresultsunder theBAUscenario,undertheRCP8.5scenariowithamoderateworldgrowthrateandworld inflation,andundertheRCP8.5scenariowithalowworldgrowthrateandhighworldinflation forfoodimports.Theeighthsectiondiscussesandsimulatestwolong-termadaptation scenariosdefinedbytheTunisianMinistryofAgricultureandsimulatesthemacroeconomic impactofthesepoliciesundertwoalternativescenarios.Thefinalsectionpresentsconcluding remarks.

TheTunisianeconomyisfacingmajorsocioeconomicdifficulties.Growingtwindeficits,slowingeconomicgrowth,depreciationoftheTunisiandinarandpersistentlyhighunemployment andinflationrateshavecharacterisedtheeconomyoverthepastdecades(Nuciforaetal., 2014).Thesestructuralweaknessesarelikelytolimitthecountry’sadaptivecapacityand increaseitseconomicvulnerabilitytoclimatechangeinthemediumandlongterm.

Sincethe2011revolution,Tunisiahasexperiencedparticularlyfragileeconomicconditions duetopoliticalandsocialinstability,whichhasledtoanunfavourablebusinessclimate forinvestmentandhamperedeconomicgrowth.RealGDPgrowthhasslowedsignificantly overthisperiodcomparedwiththepreviousdecade,fromanaverageannualrateof4.6% between2001and2010to1.4%between2011and2019,mainlyduetotheslowdownindomestic andforeignprivateinvestmentandthedeclineinexportdynamism.

Thedeteriorationininternationalfinancialconditions,combinedwiththestructuralweaknessesoftheeconomy,haslargelycontributedtotheworseningofthecountry’sinternaland externalmacroeconomicimbalances.Thetradeandbudgetdeficitshaverisentohistorically highlevels,leadingtogrowingimbalancesinthecurrentaccount,publicfinances,andthe foreignexchangemarket.

Table1:Macroeconomicindicators,source:NationalInstituteofStatistics,CentralBankof Tunisia,andauthors’computations.

Whileweakeconomicgrowthhasallowedonlymarginalgrowthingeneralgovernment resources,publicexpenditurehasrisensharplyduetoincreasesinthepublicwagebilland highersubsidiestokeepfoodandenergypricesincheckinanenvironmentofhighglobal inflationofimportedcommoditiessuchasoilandcereals.Thebudgetdeficithaswidened

rapidlyrisingfrom3.6%in2011to9.7%in2020duringtheCovid19pandemic,seefigure1a.Asa result,publicdebtincreasedsignificantly,reachingover80%ofGDPin2020,mainlydrivenby asharpriseinpublicexternaldebt,whichexceeded50%ofGDPin2020.

Inaddition,thesharpriseinthetradedeficit,mainlyduetothelargedeficitinenergytrade, persistentfooddeficits,andthedeclineintheservicessurplusduetoasharpfallintourism activity,hasledtoawideningofthecurrentaccountdeficit,whichincreasedasapercentage ofGDPfrom-4.8%in2010to-11%in2018,seefigure1b.Before2010,thecountryreliedmainly onFDIinflowstofinanceitscurrentaccountdeficit.Aftertherevolution,FDIdeclinedfrom3.5% ofGDPin2009to1.9%ofGDPin2019.Thus,thelargeandpersistentcurrentaccountdeficit wasonlypartiallycoveredbyFDIandthegovernmentresortedtoexternalborrowing,leading toanaccumulationofexternaldebtandaworseningofcountryrisk(IMF,2019).

Indeed,astheoverallfinancingneedsoftheeconomyhavesteadilyincreased,andthe contributionofthebankingsystemandhouseholdsavingstothisfinancinghasremained limited,externalborrowinghasenabledthefinancingofprivateandpublicdeficitsoverthe lastdecade.Despitelargeinflowsofremittances,whichhaveaveraged4%ofGDPoverthe lastdecade,externaldebtservicingandlargedividendpaymentsbythecorporateand bankingsectorstotherestoftheworldhaveabsorbedallexternalfinancing.Asaresult, netinternationalreserveshavedeclinedsignificantly,fallingtoonly84daysofimportsin 2018.

Duetolowhouseholdincomeandhencelowsavings,depositgrowth,themainsourceofbank financing,didnotfollowloangrowthandthebankingsectorhadtoresorttolargeamounts ofcentralbankfinancing.Liquidityinthesectorremainedbelowinternationalstandards,with liquidassetsnotexceeding20%oftotalassets.Profitabilitywasalsolow,withthereturnon equityaveraging10%between2008and2018,andthenon-performingloanratiowasvery high,averagingat13.3%in2018.(CentralBankofTunisia,2019).

(a)Budgetdeficitandpublicdebt,source:Ministryof Financesandauthors’computations.

(b)Balanceofpayment,source:CentralBankofTunisia andauthors’computations.

Figure1:FiscalBalancesandBalanceofPayments;Source:INS

(a)Budgetdeficitandpublicdebt,source:Ministryof Financesandauthors’computations.

(b)Balanceofpayment,source:CentralBankofTunisia andauthors’computations.

Figure1:FiscalBalancesandBalanceofPayments;Source:INS

Characterisedbyanaridtosemi-aridclimateover80%ofitsterritory,Tunisiahasapermanent waterdeficitandremainsthe30thmostwater-stressedcountryintheworld(WRI, 2020). Overthepastdecade,thecountryhasexperiencedtwoperiodsofseveredroughtin2013 and2015-2017,withasignificantriseintemperature,followedbyperiodsofrecurrentheat waves,aswellasfiresandfloods,whichhavemultipliedinrecentyears.Theagricultural sectorisessentiallybasedonrain-fedproduction,whichaccountsformorethan90%of thecultivatedareaand65%ofagriculturalvalueadded.Itisthereforehighlydependent onclimaticvariations(Chebbietal.,2019),asshownbythestrongcorrelationbetweenthe growthrateofagriculturalvalueaddedandrainfallinFigure2b

(a)AveragetemperatureunderRCP4.5andRCP8.5scenarios.Source:NationalInstituteofMeteorology(Climat-c, 2020)

(b)AgricultureValueAddedandrainfall.

Figure2:RecentclimaticconditionsinTunisia;Source:TunisiaNationalInstituteofMeteorology, NationalInstituteofStatisticsandauthor’scomputations.

TheupdatedprojectionsoftheNationalInstituteofMeteorologyin20201 indicateatemperatureincreaseofupto1.8°Cby2050forRCP4.52 andupto3°Cby2100.Tunisia’sinlandregions willexperienceatemperatureincreasecomparedtothecoastalregions.ForRCP8.5,this temperatureincreasewillbeevenmoreacute,reachingthevaluesof2.3°Cand5.2°Cforthe 2050and2100horizons,respectively.Underthusclimateforcing,thearidinlandregionswill experiencemajorheatwaves,threateningalreadyfragileagro-systems.

Withregardtoprecipitation,theclimateprojectionsoftheNationalInstituteofMeteorology showasignificantdecreaseinprecipitationunderthetwoscenarios,withadecreaseof between14and22mmin2050undertheRCP8.5andRCP4.5scenariosrespectively,i.e. alossof-6%and-9%comparedtotheaverageprecipitationobservedovertheperiod 1981-2010.

1Onthebasisof14regionalclimatemodelswithaspatialresolutionofupto12.5km,theNationalInstituteof Meteorologyisassessingtheimpactoffutureclimatechangeontemperatureandprecipitationfortwohorizons, 2050and2100,comparedtothe1961-1990averageunderRCP8.5andRCP4.5,presentedinFigures3aand3b 2InitsFifthAssessmentReport,theIntergovernmentalPanelonClimateChange(IPCC)presentedthemodelling ofgreenhousegasesthroughRepresentativeConcentrationPathway(RCP)scenariosthatincludeapessimistic scenarioRCP8.5,twointermediatescenarios(RCP4.5withastabilizationofemissionsbefore2100atalowleveland RCP6.0withastabilizationofemissionsbefore2100atamediumlevel),andanoptimisticscenarioRCP2.6(IPCC, 2014).

Theclimatescenariosalsopredictasignificantincreaseinclimateextremes,indicatinga longerdurationofheatwavesandahighfrequencyofdroughtsandfloods.Indeed,Tunisia wouldexperienceanincreaseinthenumberofconsecutivemaximumdrydaysonaverage of9.3daysperyearaccordingtoRCP4.5and17.1daysperyearaccordingtoRCP8.5scenario, i.e.anincreaseof11%and19%respectivelycomparedtotheaveragerecordedovertheperiod 1981-2010.

Withthepredictedincreaseintemperatureanddecreaseinrainfall,thelossofagricultural productioninTunisiaislikelytoworseninthecomingdecades.Tunisianagriculturehas alreadyexperiencedtheseverenegativeimpactsofclimatechangeincertainpartsofthe country.Risingsealevelsduetoclimatechangehaveincreasedcoastalerosionandsalinity contaminationofcoastalaquifers(Brahmietal., 2018).Thesecoastalaquifersareused byfarmersforirrigation,whichhasledtothesalinisationofseveralirrigationperimetersin Tunisiaandtheirpermanentloss.Forexample,accordingtoIssametal.(2022),theaquifer ofthecoastaltownofDyiar-Al-HujjejinCapbonhasexperiencedseawaterintrusion.The salinisationoftheaquiferreachedaveryhighelectricalconductivityof15dS/minthe1990s, causingmanylocalfarmerstoabandontheirplotsandwells.Inaddition,salinityhasreduced plantgrowthandwaterquality,resultinginlowercropyieldsandreducedwaterreservesin

livestock.

Asincoastalareas,thevulnerabilityoflandintheinteriorofthecountry,whichisclassifiedas semi-arid/arid,iscompoundedbyadverseclimaticconditionsandunsustainableagricultural practices.InTozeur,wherethelargestoasisfarmingsystemislocated,datecropsareatrisk, sufferingthefullimpactofclimatevariabilityandpoorsurfaceirrigation(Dhaouadietal., 2017).Muchofthelandoccupiedbysmallholdersisonlow-fertilityland,whereinappropriate agriculturalpracticeshaveledtosoilerosionandlossofbiodiversity.Irrigationwithhighly salinewaterhasledtothedegradationoreventotalsterilisationofasignificantproportionof Tunisiansoils(KhawlaandMohamed,2020).Indeed,inTunisia,irrigationwateristhemain sourceofsalinisationinirrigatedareas(Louatietal.,2018).

FutureclimatechangeisexpectedtoraisesealevelsalongtheTunisiancoastlineby30to 50cm,leadingtolossofarablelandandacceleratedsalinisationofgroundwaterincoastal areas.Inaddition,soildegradation,increasedheatwavesanddroughts,andreducedrainfall willleadtoageneraldeclineinyieldsandcultivatedareas,resultinginlossesinagricultural production.

InordertoanalysetheimpactofdecliningagriculturalproductionontheTunisianeconomy, wefirstconstructproductionprojectionsintonnesfortwenty-twodifferentagriculturalcrops underBusinessAsUsual(BAU)andtheRCP8.5scenarioforthe2022-2050timehorizon. Ourcropbasketcoversallagriculturalproduction.InourBAUscenario,weuseprojections fromtheFAO’sGlobalAgro-ecologicalZones(GAZ)model(Fischeretal., 2021)toproject productionlevels.3 Forthemaincerealcrops(durumwheat,softwheatandbarley)andolives, wequantifytheimpactofclimatechangeonharvestedareasandcorrespondingyieldsunder theRCP8.5scenariothroughprojectionsdevelopedundertheAdapt’Actionproject,with theparticipationoftheTunisianMinistryofAgricultureandtheFrenchDevelopmentAgency (Deandreisetal., 2021).FortheremainingcropsnotcoveredbytheAdapt’Actionproject (dates,citrusfruits,tomatoes,potatoes,onions,peppers,livestock,milk,eggs,watermelon, othercerealsandothervegetables&fruits),weuseprojectionsbythe Foodandofthe UnitedNations(2018)undertheStratifiedSocietiesScenario(SSS).

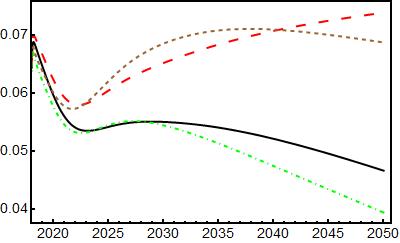

Figure4ashowstheaveragesmoothedgrowthratesofyields(intonnes)ofourcropbasket fortheBAUandRCP8.5scenarios.Asexpected,projectionsundertheRCP8.5scenarioshow significantlossesforthemaincropsgrowninTunisia.Amongcereals,barleyandsoftwheat productionin2050areprojectedtodecreasebyrespectively0.9%and0.2%peryear,while durumwheatisprojectedtoincreasebyonly0.1%over2022-2050period.

Themainexportcommodities,i.e.datesandolives,willalsobeseverelyaffectedbyfurther increasesingroundwatersalinityindeepaquifersinsouthernregions,fordates,andbyloss ofrainfallandincreasedtemperaturesforolives.Accordingtoprojections,datesproduction willdeclineby2%peryearuntil2050,whileoliveproductionwilldeclineby0.5%.Livestock production(cattle,goat,sheep)willalsofallasfeedlossesincrease,leadingalsotolowermilk productionby2050.Thegrowthrateofpoultryproductionwillslowdowntoonly0.2%,which willalsobetherateofgrowthofeggproduction.AccordingtoMedECC(2021),astructural shiftinfisheryresourcesisexpected,withanincreaseinthermophilic,exoticspeciesanda

3Morespecifically,forourBAUscenario,weuseagriculturalproductionprojectionsreportedinthe’ClimateShifter’ socio-economicpathwayprovidedbyFAO,whichcorrespondstotheRCP6.0climatescenario

(a)Cropsaverageannualgrowthrateover2021-2050 forBAUandRCP8.5scenarios.Source: Deandreisetal. (2021);FoodandAgricultureOrganizationoftheUnited Nations(2018)andauthors’computations

(b)Demandcomponentsofdomesticagricultureproduction(involume)underBAUandRCP8.5scenarios.Source: Deandreisetal.(2021);FoodandAgricultureOrganization oftheUnitedNations(2018)andauthors’computations

Figure4:AgriculturalProductionProjections.Source:Author’scalculations

simultaneousdecreaseincurrent,coldaffinityspecies.Soweassumethatfishproduction remainsstableandfixtoits2021value.Insummary,thetotalagriculturalproduction(in addedtonnes)sectorwilldeclinebyanaverageof0.5%peryear.

Inordertousethesevolumeprojectionsinoureconomicmodel,weclassifycropsaccordingto theiruse,usinginformationfromthe2015product-levelsupply-usetable(SUT)foragricultural commodities.Morespecifically,weallocatethesupplyofeachcropintonnestosatisfy threecategoriesofdemand:householdconsumption,intermediateconsumptionbyagroindustry/othersectors,andexports.Wethenuse2017pricesforeachcroptocalculate thevalueofoutputforconsumption,intermediateconsumptionandexportsinconstant prices.

Figure4bshowstheevolutionoftheproductionofagriculturalconsumergoods,intermediate consumptiongoods,andagriculturalandprocessedfoodexportsinconstantpricesunder theBAUandRCP8.5scenarios.5 Allfourproductioncategoriesshowcontinuousandsustained declinesuntil2050.Withagrowingpopulationandincreasingdemandforfood,thisdecline inproductionwillleadtoincreasedfoodimportstomeetdomesticdemand,increased ruralunemploymentandpossiblymigrationtourbanareas.Combinedwiththedecline inagriculturalandagro-industrialexports,Tunisiafacesasignificantlossofvitalforeign exchange,especiallyifglobalfoodpriceinflationishighinthecomingdecades.Inthenext section,wediscussthemainaspectsofalarge-scale,empiricalstock-flow-consistentsystem dynamicsmodeloftheTunisianeconomytocapturetheimplicationsofthesedevelopments forTunisia’smacrodynamicperformance.

4Asdiscussedinthenextsection,exportsofagro-industrialgoodsdependsolelyonprojectedoliveandfish production.Fromtheseprojectionsanexogenousexportpathfortheprocessedfoodisconstructed.

5Notethatthefigureusesactualproductiondatauntil2021andprojectionsfrom2022onwards.Theincreasein theproductionofintermediateagriculturalgoodsbetween2018and2020ismainlyduetohigholiveproductionin 2018and2020andhighdurumwheatproductionin2019.However,thesetrendsarenotmaintainedin2021and2022, whendroughtandheatwaveshaveastrongnegativeimpactonyields

TheGEMMES-Tunisia6 modeldescribestheevolutionoftheTunisianmacroeconomyunder differentclimatechangeandclimateadaptationscenarios.Thetechnicaldescriptionofthe modelwithdetailedequations,informationonthedata,calibrationandsimulationstrategies canbefoundintheAppendix.ThestructureofthemodeliscapturedbytheTransactionFlow Matrix(TFM,Table2)andtheBalanceSheetMatrix(Table3),whichshowthebalancesheet structureofeachsector,andthetransactionsthattakeplaceintheeconomybetweenthe institutionalsectorsrespectively.NotethattheTFMalsorecordsthenetsavingpositionsand thecorrespondingchangesinthefinancialandrealstocksofthemodel.Assetsandinflows areindicatedbya(+)andliabilitiesandoutflowsbya(-).

Themodelhassixinstitutionalsectors:Firms,Households,Banks,Government,CentralBank andtheRestoftheWorld.Thefirmssectorisfurthersubdividedintotheagriculturalsector andthenon-financialcorporations(NFC)sector.Therearefivetypesofcommodities.Three differentagriculturalproductsforhouseholdconsumption,intermediateconsumptionand exportsrespectively,producedbytheagriculturalsector;aprocessedfoodproductproduced bytheNFCsector,whichisusedforintermediateandfinalconsumption,andanon-food productalsoproducedbytheNFCsector,whichisusedforinvestment,intermediateandfinal consumption.Inthiscontext,particularattentionispaidtothemacro-financialconditions affectingproductionandthedevelopmentofinternalandexternalimbalances,including foodandconsumerinflation,unemployment,theaccumulationofprivateandpublicdebt, thedeteriorationofcountryrisk,externaldeficitsandtheaccumulationofforeigndebt,and theassociatedfinancialacceleratoreffectsthatfeedbackintospendingdecisionsinall sectors.

Domesticagriculturalproductionforfinalconsumptiondemand,intermediateconsumption andexportsisgivenbytheprojectedclimateconditionsasdescribedintheprevioussection, andisexogenoustothemodel.Aggregatedomesticdemandforagricultureiscomposedof finalconsumptionandintermediateconsumption.Anyexcessdomesticdemandiscovered byimportstoclearthemarket.Theagriculturalsectorconsumesasintermediateinputs agriculturalgoods,processedfoodgoodsandNFCgoods,infixedproportionsofitstotal production.Similarly,thesectoruseslabourandcapitalinfixedproportions.Employment isdeterminedbytotalproductionandtheconstanttrendinlabourproductivity.The agriculturalsectorismostlyhousehold-ownedandthereforeitgeneratesmixedincomefrom itsproductionactivities,afteraccountingforallthetaxesinproduction,socialcontributions andsubsidies.Giventheexogenousgrowthofproduction,itisassumedthatthesector operatesatafixedcapitaltooutputratio,andinvestmentisalwayscarriedouttoensure thatthecapitalstockissufficientforthegivenproductionpath.Netprofitsaredefinedbythe 6

GEMMESstandsforGeneralMonetaryandMultisectorialMacrodynamicsfortheEcologicalShift.mixedincomeofthesectorfromwhichinterestpaymentsonserviceableloans,insuranceand commissionspaidtothebankingsectorandincometaxestothegovernmentarededucted. Aproportionofnetprofitisretainedtofinanceinvestmentandremainingfinancingneeds arecoveredbynewborrowingfromthebankingsectorindomesticcurrency.

TheNFCsectorproducestwogoods,processedfoodandannon-foodgood,withtwodistinct productionprocesses.Domesticproductionoftheprocessed-foodgoodisdemandedfor finalandintermediateconsumption,andexports.Thenon-foodgoodisfurtherdemanded forinvestmentbyfirmsandhouseholds.Aswithagriculturalproduction,intermediate consumptionfunctionsaregivenbythetechnicalcoefficientsandthelevelofproduction forbothgoods.Thesectoruseslabourandcapitalinfixedproportions,andemploymentis determinedbytotaloutputandlabourproductivity.Duetothedependenceoftheprocessed foodproductiontoagriculturalintermediateinputs,wefurtherassumethatprocessedfood exportsdependonclimaticconditionsandareexogenoustothemodel.Importsofprocessed fooddependontimevaryingimportpropensitiesoutofreallevelsoffinalandintermediate consumption.Theimportpropensitiesgraduallyadjusttotheirtargetlevels,whichdependon relativeprices(takingintoaccountimporttaxes)andrelativeproductivitybetweenTunisia andtherestoftheworld,withdifferentelasticities.

Domesticproductionofthenon-foodgoodissoldforfinalandintermediateconsumption, investmentandexports.Asintheothersectors,fixedproportionsofintermediateinputs,labour andcapitalisassumed.Importsofnon-foodgoodsaredeterminedbydomesticdemand forprivatefinalconsumption,intermediateconsumptionandinvestment,withendogenous importpropensities.Aswithprocessedfoodgoods,importpropensitiesareslow-movingand dependonrelativepricesandrelativeproductivitylevels.Exportsofnon-foodgoodsdepend onforeignGDPwithanendogenouspropensitytoexportthatdependsonrelativepricesand relativeproductivitylevels.

Theprocessedfoodanddurablegoodmarketsarecharacterisedbydisequilibria.Ateach pointintimeandforeachgood,totaldemandisnotnecessarilyequaltototalproduction. NFCfirmsformadaptiveexpectationsonrealexpecteddemandaroundthetrendgrowth ofprocessedfoodandthedurablegoodsales.Thistrendfollowspopulationgrowthrate forprocessedfoodandcapitalaccumulationfornon-foodgood.Excessdemandorsupply isclearedbyinventoryadjustmentsinbothmarkets.NFCfirmshaveadesiredinventory toexpectedsalesratiosforprocessedfoodandnon-foodgoods,whichdeterminedesired inventories.Therefore,totalproductionisbasednotonlyonexpecteddemand,butalsoto attaindesiredinventorylevels.

Theproductivesectorchargesarangeofdifferentprices.Themodeldistinguishesbetween producerpricesandusageprices,i.e.intermediateconsumption,finalconsumptionand investment,bythetypeofgood,i.e.agricultural,processed-foodandnon-foodgood.Itfurther distinguishescommodityspecificinternationalimportandexportprices.Firmssettarget producerpricesbasedonamarkupoverhistoricalunitcostsandgraduallyadjusttothese targets,witharelaxationspeedinverselyproportionaltonominalrigidity,capturingprice inertia.Then,thedifferentcompositeusagepricesfollowproducerprices,afterconsidering alltherelevanttaxes,subsidiesandmargins,andaccountingfortheimportsharesof intermediateandfinalconsumption,andthecorrespondingeffectsofworldpricesand thenominalexchangerate.Theagriculturalmarkupisfixed.Themarkupsonprocessedfood andnon-foodgoodsdependnegativelyonthedivergencebetweentheactualandadesired inventorytooutputratios.Thus,asunwantedinventoriesaccumulate,producersreducethe mark-ups(andviceversa).Notethatbyseparatelytrackingdownthedifferentprices,the modelcomputesfoodinflationandalsohouseholdCPIinflationthroughaCPIindex,which dependsontheconsumerpricesofeachproductandtheircorresponding,time-varying relativesharesintheconsumptionbundleofhouseholds.

Asstatedabove,theagriculturalsector’sinvestmentisdeterminedbytheconstantcapital tooutputratioandtheexogenous,climatedependent,productiontrajectory.NFCfirms’ investmentdecisionsdependonsectoralprofitability,whichiscapturedbytherealrate ofprofit.Themodeltracksdownexplicitlytheformationofgrossoperatingsurplusfrom bothprocessedfoodandnon-foodgoodproductionprocesses,includingthegood-specific margins,subsidiesandtaxesonproduction7.Grossprofitsaredefinedafterconsideringthe interestreceivedontheirdeposits,interestpaidontheirserviceabledomesticandforeign currencyloans,insuranceandcommissionsthatfirmspaytothebankingsector.Netprofits istheresidualafterfirmspaycorporatetaxes.Netofinflation,netprofitsformtheprofitability ofthesector.Then,firmsdistributepartoftheprofittodomesticandforeigninvestorsas dividends.

7Inreality,partofproductiontakesplaceinhouseholdsandthereforehouseholdproducersalsogenerategross operatingsurplus.Themodelassumesthatallproductiontakesplaceinfirms.Inorderthentomatchempirically thenationalaccountsandespeciallythesectoralsavingpositions,aproportionofthegrossoperatingsurplusthatis generatedbyfirmsisdistributedtohouseholds,whichisthentaxedbythegovernmentalongsidetheirothersources ofincome.

Firmsfinanceinvestmentthroughretainedearningsandexternalfinance.Theyfurtherrequire fundingtokeepdepositsinbothdomesticandforeigncurrenciesforworkingcapital.Firms desiretofinanceaconstantproportionoftheirtotalfinancingneedsthroughFXdenominated loans.Themodelassumesthatcreditprovisioninforeigncurrencyisrationed,andonlya fractionofthedesiredcreditisprovidedbythebankingsectorinFX.Theremainingfinancing needsaresatisfiedthroughcreditprovisioninginthedomesticcurrency.

Asmentionedabove,banksholdsavingandcurrentaccountdeposits,provideforeignand domesticcurrencyloans,provideinsurancetocompaniesandreceivecommissionsfortheir services.Theyalsoholdgovernmentbondsascollateral.Akeyvariabledeterminingthe availabilityofcreditandtheliquidityoftheFXloanmarketiscountryrisk.Indeed,boththe rationingofcreditvolumeandtheinterestrateschargedonFXloansdependoncountryrisk. Inturn,thecountryriskisaconvexfunctionofthecountry’sinternationalinvestmentposition (ignoringforeign-ownedequityofdomesticfirms),highlightingthesensitivityofsmallopen economiessuchasTunisiatotheperceivedsustainabilityoftheexternaldebtbyinternational investors.

Thecostofforeigncurrencydenominatedprivatedebtdependsonapremiumovertheworld interestrateandisaconvexfunctionofthecountryrisk.Thetargetinterestratethatbanks payondepositsisdeterminedbyamarkdownfromthepolicyratesetbythecentralbank. Themarkdown,inturn,dependsontheliquidityneedsofthebankingsector,andincreases asthebankingsector’sassetsideofthebalancesheetexpandsrelativetoliquidityneeds, capturedbythethebank’sassets-to-advancesratio.Inaddition,thedomestictargetlending ratedependsonthedomesticpremiumovertheaveragecostoffundingforbanks.The domesticpremiuminturndependsontheratioofdebttogrossoperatingsurplusofthe NFCsector.Iftheprivatedebtburdenishighrelativetotheprofitabilityofthesector’smain economicactivity,bankswillraisetheinterestratetocompensateforahigherperceivedrisk ofdefault.Forsimplicity,itisassumedthatthelendinginterestratechargedtohouseholdsis aconstantmarkupoverthelendingratechargedtofirms.Actualeffectiveratesgradually adjusttotargetswithrelaxationspeedsthatdependontheinverseoftheaveragematurity ofloans/deposits.

Banksmakeprofitsfromtheinteresttheyreceiveonserviceableloansfromtheprivatesector, couponpaymentsongovernmentbonds,commissionsandinsurance,afterdeducting theirfundingcosts,i.e.interestpaidonsavingdepositsandadvances,wagesandsalaries ofpersonsemployedinthebankingsector,employers’socialcontributions,intermediate consumptionandothertransferstothegovernment.Wealsoassumethatinsuranceservices totheproductivesectorsoftheeconomyareconstantproportionsofthenominalvalueofthe capitalstockineachsector.Itisalsoassumedthatcommissionsareproportionaltothetotal debtoftheprivatesector,includinghouseholds.Asinothersectors,grossprofitsaretaxed bythegovernment.Partofnetprofitsisdistributedtodomesticandforeignshareholders throughdividends,andtheretainedearningsincreasebanks’ownfundstosatisfyariskweightedtargetcapitalratio(BankforInternationalSettlements,2017).Notethatafraction ofagriculturalloans,mortgagesandcorporateloansisnon-performing(NPLs).Thelower thelevelofeconomicactivity,asmeasuredbyunemploymentandrealGDPgrowth,the higheristheproportionofNPLs.InflationtendstoreducetheamountofNPLs,ashigher nominalincomesmakeiteasiertomeetpaymentobligations.Finally,ahigherreturnon equityallowsbankstofinancelessriskyinvestmentprojects,therebyreducingthelikelihoodof

non-performingloans(MessaiandJouini,2013;Abidetal.,2014;RomdhaneandKenzari,2020). Notethatemploymentinthebankingsectorisaconstantfractionofactivepopulation.

Inreality,banksreceiveinterestonserviceableloansandpayinterestonsavingsdeposits, asrecordedintheTFM 2.Notehowever,thatinthenationalaccounts,theoutputofthe financialsectorincludesfinancialintermediationservicesindirectlymeasured(FISIM).FISIMis anaccountingconventionthataimstocapturefinancialintermediationanddividesinterest paymentsasfollows.Anamountthatcorrespondstotheinterestchargedbybanksfor providingloanablefundstoinvestors,calculatedastheinterestpaymentsresultingfroma ratespreadbetweenthelendingrateandthereference(policy)rate,plusanamountthat correspondstotheinterestbankspaytosavers,calculatedastheinterestpaymentsfroma ratespreadbetweenthedepositrateandthereferencerate.Putsimply,ifcreditoperated throughaloanablefundsmarketandifsavingsandinvestmentequilibratedthroughthe naturalrate,FISIMwouldcorrespondtowhatbankswouldcharge(markup)toinvestors pluswhatbankswouldretainfromsavers(markdown),overthenaturalrateofinterest. NationalaccountsthenproceedbydistributingFISIMasfinalandintermediateconsumption offinancialservicesbynon-financialcorporationsandhouseholdsandtreatitasgrossvalue addedfromfinancialintermediation.TheremaininginterestpaymentsnotrecordedasFISIM, i.e.interestpaidondepositsandreceivedonloans,calculatedusingthereferencerate,is thenrecordedundertheprimarydistributionofincomeaccounts8 .

However,itiswellestablishedthatbanksdonotactasintermediariesinaloanablefunds marketwhenprovidingdomesticcurrencyloans(McLeayetal.,2014).Indeed,becauseofthe model’sendogenousmoneyframework,thereisnoreasontotreatbanksasintermediaries. WethereforeconsideralltheFISIMrecordedinthenationalaccountsasamarginoninterest ratesandshiftittointerestpayments.Consequently,thegrossoperatingsurplusandthe valueaddedgeneratedbythebankingsectordifferfromthenationalaccountsandtherefore arenotreported,andnominalGDPismeasuredonlythroughfinalexpenditure.Sincewetreat thebankingsectorasanon-productivesector,weunderestimatenominalGDPbyanamount equaltoFISIMpaidtohouseholdspluscommissionsandinsurancecostsofhouseholds 9.In orderthentomatchempiricallythenominalGDP,weaddtofinalexpendituresthemissing financialconsumption,i.e.insuranceservicesandcommissionspaidbyhouseholdsand householdFISIM(seeequation267and268intheAppendix).

Thegovernmentprovidespublicservicesbyemployingaconstantproportionofthetotal populationaspublicservants.Italsoinvestsinpubliccapitalataconstantrate,andinadaptation(irrigationmainlyaswewilldiscussbelow)dependingontheclimatechangescenario simulated.Totalgovernmentoutputisthereforecomposedofthelabourcostsofgovernment employees,totalpublicintermediateconsumption,employer’ssocialcontributionspaidby thegovernmentanddepreciationofpubliccapital,asinSystemofNationalAccounts(SNA). Governmentalsoprovidessocialbenefitsandwelfareprogrammes,whichareassumedto bepro-cyclical,dependingontheunemploymentlevelandtheaverageprivatewagelevel. Totalpublicexpenditureisgivenbythesumofpublicemployees’wagesandemployer’s socialcontributions,intermediateconsumptioninputs,socialbenefits,investmentinpublic capitalandadaptation,andinterestpaidonoutstandingpublicdebt.

Governmentrevenueisdeterminedbythesumofemployers’socialcontributions,workers’

8See(ZezzaandZezza,2019)forasimilardiscussion.

9TheFISIMthataccruestoNFCsandthecommissionandinsuranceservicesconsumedbyNFCsincreasethe grossvalueaddedofbanksbythesameamountthattheyreducethegrossvalueoffirmssotheydonotneedtobe addedtothenominalGDPcalculationsfromthedemandside.

socialcontributions,VATinthethreegoodsoftheeconomy,importtaxes,taxesonproduction andothertaxesonproducts,dividendsfrompublicenterprises,centralbankprofits,and incometaxes.Thepublicdeficitisfinancedbyborrowing.First,thegovernmentborrows partofitstotalfinancingneedsasforeigncurrency(FX)denominatedloansataconstant proportionofthetradedeficit10,andtheremainingneedsarefinancedbydomesticcurrency bonds.Itisassumedthattheinterestrateonforeigncurrencypublicbondsdependsonthe countryrisk,whiletheinterestrateonthedomesticcurrencybondsdependsontheratioof publicdebttoGDPandCPIinflation.

Aswiththebankingsector,wetreatthepublicsectorasanon-productivesector.This meansthatproduction,andhencefinalandintermediateconsumptionofpublicservices asmeasuredbytheNSAframework,isnotexplicitlytrackedintheTFM.Therefore,inorder totracknominalGDP,weaddtofinalexpenditurethenominaldepreciationofthepublic capitalstock,theemployer’ssocialcontributionspaidbygovernment,publicwagesand government’sintermediateconsumptiontoaccountfortheproductionandthereforefinal consumptionofpublicservices.

Thecentralbankfollowsapureinflation-ratgetingTaylorrulewhensettingthepolicyrate andactsaslenderoflastresorttothebanks,providingliquiditytothebankingsectoron demandthroughcentralbankadvances.Italsobuysafixedfractionofpublicbondsateach pointintime.Anyprofitsmadebythecentralbankaredistributedtothegovernment.

Employmentinthemodelisdemanddrivenbymarketconditions,andpartlysupplyconstrained,byclimatechange.Asexplainedabove,employmentintheagriculturalsectoris drivenbyclimatechange,andacomponentofdemandforprocessedfood,i.e.exports,is alsodirectlyaffectedbyclimatechange.Fortherestoftheproductiveactivities,expected salesdetermineproductionandthereforeemployment.

Themodeldoesnotidentifydistinctsocialclasseswithinthehouseholdsector.However, tocapturethedifferentpositionsinthesystemofproduction,wedistinguishbetweentwo sourcesofincome.First,householdsearnnetdisposablewageandproductionincomefrom theemployedpersonsintheprivateandpublicsectors,afterconsideringtheincometaxes, socialbenefitsandworkers’socialcontributions.Second,householdsearnnetfinancial incomeintheformofdividendsandprofitsfromtheproductiveandbankingsectors,interest incomeonsavingsandcurrentdepositsandremittancesfromtherestoftheworld.Non-wage incomeisnetofinterestpaidonserviceablehouseholddebt,commissionsandinsurance paidtobanks.

Inallthesectors,i.e.agriculture,NFCs,banksandgovernment,nominalwagesarefully indexedtoinflationandproductivitygrowth,keepingrealwagesconstant.

Householdshaveatargetlevelofnominalconsumption,whichdependsonatime-varying marginalpropensitytoconsumeoutofnominalincome;thepropensityisanegativefunction oftherealdepositrateashouseholdshaveanincentivetosavemorewhenthedeposit

10Thedecisiononwhatproportionofnewdebtwillbeinforeigncurrencydependsonanumberoffactorsand considerations,suchasarbitrageopportunities,riskmanagementandotherpolicyobjectives.Wedisregardthese considerationsinthislong-runmodelanduseafixedratioforpublicFXborrowingtothetradedeficit

rateishigher.Actualconsumptionadjustsgraduallytoitstarget,witharelaxationspeed thatcaptureshabitformation.Oncetotalconsumptionisdetermined,householdsallocate theirincomebetweenagriculture,processedfoodandthenon-foodgoodthroughalinear expendituresystem(LES)asinLluch(1973).However,withfixedmarginalbudgetshares,LES violatesEngel’slawthatmarginalincomeelasticitiesoffoodmustdecreasewithgrowing income(seeHoetal.(2020)).We,therefore,assumethatthemarginalbudgetsharesof agriculturalandprocessedfoodarenegativefunctionsofrealconsumption.Householdsalso haveatargetinvestmentinhousing,definedasafractionoftheirtotalnetdisposableincome, andactualhouseholdinvestmentgraduallyadjuststothistarget.Aconstantproportionis financedthroughbankinglendingandtherestthroughthenetdisposableincome.

Householdsdistributetheirsavingsinforeigncurrencydeposits,savingandcurrentaccount depositsindomesticcurrencyandgovernmentbonds.Foreigncurrencydepositsarea shareoftotalremittancesreceivedfromabroadandcurrentaccountdepositsareashare ofconsumptionfortransactionpurposes.Aconstantshareoftheremainingsavingsis investedingovernmentbondsandtheresidualsavingsareheldassavingaccountdeposits indomesticcurrency.

Theforeignexchangemarketischaracterisedbyadisequilibriumbetweentheflowofforeign exchangedemandandsupply,asinCharpeetal.(2011).Therefore,thenominalexchange rate,measuredasdomesticcurrencyperunitofforeigncurrency,increases(decreases)with excessdemand(supply).Totaldemandforforeignexchangeisgivenbythesumofimports, theincomeaccount,i.e.theinterestpaymentsonforeignexchangedebtanddividendspaid totherestoftheworld,andtheflowdemandofthebankingsector,whichisdeterminedby the’no-FX-openposition’requirement.Totalforeignexchangesupplyisgivenbythesum ofexports,FDIflows,remittancesandothertransfersfromabroad,cross-bordercreditand foreignexchangedepositinflowstotheprivateandgovernmentsectorsand,dependingon thesimulatedscenario,concessionalloanstothegovernmentthatfinancepublicadaptation investment.

Thestock-flowconsistentstructureofthemodelisparticularlysuitableforstudyingexternal imbalances,thevulnerabilityofcountriestofinancialcrisesandthemacro-environmental channelsthatcanpropagatetheenvironmentaldamages,sincethemodeltracksnotonly theevolutionofcurrentaccountimbalancesandthefirst-roundnegativeeffectsofclimate damagesonthetradebalance,butalsothegrossexposuretoexternalfinancialrisks,which isusuallyneglectedwhenassessingexternalimbalances(BorioandDisyatat,2011,2015).The latterisexplicitlytrackedbytheendogenousinternationalinvestmentposition,aswellasby thedynamicsofavailableforeignexchangereserves.Furthermore,themultisectoralstructure allowsforadetailedexaminationofhowsuchfinancialrisksaredistributedwithinthecountry throughtheaccumulationofexternaldebtinthebalancesheetsofallinstitutionalsectors, andallowsfordetailedfeedbackeffectssuchaspriceeffects,throughtheevolutionofthe interestrates,andquantityeffects,suchasthequantityrationingintheforeignexchange market,theevolutionofdomesticnon-performingloansandtheoverallindebtednessofthe Tunisianeconomy.

Inordertocalibratetheparametersofourmodelweutilizeawidevarietyofeconomic data,listedinTable 4.TheCovarianceMatrixAdaptationEvolutionStrategy(CMA-ES) (HansenandAuger,2011)isusedtoempiricallyfitthemodeltoTunisianmacroeconomicand financialdataforvariablesforwhichwehaveasatisfactorilylargedataset.TheCMA-ESis

astochastic,evolutionaryoptimisationalgorithmthatisappropriateforthecalibrationof complex,nonlinearsystemsofdifferentialequationsasitallowsforanefficientexplorationof theparameterspace.Usingablockapproachandtakingintoaccounttheavailabledata,the calibrationoftheparameterswascarriedoutforfiveblocksrelatingtoproductionandpricing inprocessedfoodandnon-foodgoodsectors,consumption,imports,exports,andnonperformingloans.Theiterativeprocedurethatwasutilisedinthecalibrationprocessesisthe following.Anobjectivefunctionisdefined,whichmeasuresthedifferencebetweenthemodel’s predictionandactualdata.Then,theparameterspaceisdefinedthrougharangeofplausible parametervalues.Avectorofparametervaluesisrandomlyinitialisedandthesystemis simulatedthrougha4thorderRunge-Kuttamethod.Thecandidatesolutionsareevaluated andbasedontheirfit,themeanandcovariancematricesoftheparameterdistributionare updated.Then,anewparametervectorissampledfromtheupdateddistribution.Thelast twostepsareiterateduntilthealgorithmconvergestoasatisfactorysolution.Weprovidea completelistofparametersintheAppendix,withtheirvalues,definitionsandhowtheywere obtained.Forparametersforwhichanestimationwasnotpossibleduetothelackofalarge enoughsample,weusedthedataattheinitialpointofsimulationsforcalibrationtoensure thatthemodelreplicatestheeconomicdataaspreciselyaspossible.

SourceData-set

NationalInstituteofStatistics(INS)

CentralBankofTunisia

MinistryofAgriculture/NationalObservatoryofAgriculture

MinistryofFinances

UNCOMTRADE,WorldInternationalTradeSolution (WITS)

IntegratedEconomicAccounts(IEA),MacroeconomicAggregates,Supply-UseTable,FlowofFunds(FoF),Populationand LabourMarketStatistics

BalanceofPayments(BoP),InternationalInvestmentPosition (IIP),NetBankingProducts,ExchangeRates,ExternalDebt, Loansbysector,BondsandInterestRatesStatistics

DomesticproductionbycommodityinAgricultureSectorin quantity(Tonnes)andValue(TunisianDinar),Commodity prices

PublicDebt,Publicfinancialindicators,Taxesonprofitsand income

Imports/Exportscommodityinquantityandvalue(HS-6digits,Imports/ExportsCommoditypricesinDollar,Importsshare forconsumption,intermediateconsumptionandinvestment bysector(A,PFandF)

LaborproductivityinTunisiaandtheRestoftheWorld InternationalMonetary Fund FinancialSoundnessIndicators(FSI),IntegratedMonetary Statistics;BanksandCentralBank’sBalancesheet

PennWorldTable(PWT)

Table4:MaindatasetsusedtodeveloptheSFCempiricalmodel

InordertosimulatetheeffectsoflossesinagriculturaloutputontheTunisianeconomy,we makecertainassumptionsonthefutureevolutionoftheexogenousvariablesinthemodel. ThesevariablesandthedifferentscenariosontheirdynamicsarelistedinTable5below.

Forourinitialanalysis,weconstructthreedifferentscenarios:Thebusinessasusualscenario (BAU)definedabovewithnochangeincurrentmacroeconomicpolicies;anoptimistic scenarioinwhichwetakeintoaccountthelossesinagriculturalproductionundertheRCP 8.5projectionsbutassumethatfoodpricesriseinlinewithgeneralworldinflation(scenario RCPLI);andapessimisticscenarioinwhichweassumethatfoodpriceinflationexceeds

generalworldCPIinflationoverthenextthreedecades(scenarioRCPHI).11 Table5displays thesmoothedannualgrowthratesassociatedwithFigure4bofagriculturalproductionfor consumption(grypac),forintermediateconsumption(grypaic),forexports(grypaw)andgrowth rateofprocessedfoodexports(grPF X ).Forallscenarios,wesettheworldinflationrateof non-foodgoods(Inf NF,w)atthreepercent,whichistheaverageofthelasttwodecades. Throughoutthesimulations,weassumethatthetermsoftradeforallgoodsremainthesame, sothatinflationinimportsofnon-food(inf NF,w),processedfood((inf PF,w))andagricultural goodsforconsumption(Inf A,w C )andintermediateconsumption(Inf A,w IC )areequaltoinflation inthepricesofexportsofthesegoods(Inf NF X , Inf PF X and Inf A X respectively).Wecalibratethe labourproductivitygrowthfunction(seeAppendix,equations248-249)tosetitsvalue(gra) equaltoitsaveragevalueoverthelasttwodecadesinTunisiaat1.5%.Wealsoassumeno catching-uporlaggingintermsoflabourproductivitygrowthbetweenTunisiaandtherest oftheworldandthuswealsosetthegrowthrateoflabourproductivityintherestoftheworld ( graw)at1.5%.Thegrowthratefortheworldeconomy(grw)isfixedarounditsaveragevalue inthelasttwodecadesatthreepercentinallthescenarios.ForTunisia’spopulationgrowth rate(αpop),weuseUN’s’highvariant’scenarioprojectionswithanadditionalassumptionthat labourforceparticipationrateincreasesby4%overthenextthreedecadesandwesmooth thegrowthrateto0.7%peryear.

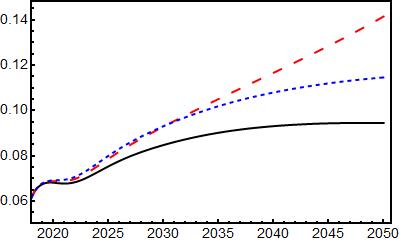

Thegraphsoffigure6showtheresultsofthesimulationsfortheBAUandthetwoRCP8.5 scenarios(RCPLIandRCPHI)describedabove.12 OurBAUscenariograduallystabilisesjust below13%unemploymentrateandgeneralinflationfallsbelow5%.Bothagriculturaland processed-foodinflationremainclosetothegeneralinflationrate.Similarly,economicgrowth isabove2%inthelongrun,inlinewithpopulationandgeneralproductivitygrowth.Inthe longrun,thepublicdeficitisaround5%ofGDPandthepublicdebtstabilisesat90%ofGDP. Startingfromover13%ofGDPinearly2018,thetradedeficitsettlesaround9%inthelong

11Thisisessentiallythedisturbingobservationofthelastdecade,asdocumentedbyBogmansetal.(2021).

12Wedonotbringtheeconomytoasteadystate,butsimulatethemodelstartingfromtheactualvaluesofthe Tunisianeconomyattheendof2017.Therefore,thedisequilibriumadjustmentprocessesleadtofluctuationsinthe modelbeforestabilising.Infact,withoutlaggingproductivitygrowthrelativetotherestoftheworldandduetothe largedepreciationofthenominalexchangeraterelativetodomesticinflation,therealexchangeratedepreciatesat thestartofallsimulations,leadingtoanexport-ledgrowthspurtthatstabilisesasthemacro-financialfeedback loopstakeeffect.

run,leadingtoacurrentaccountdeficitofroughly7%ofGDP.Astheexternaldeficitsettles downtoitslong-runvalue,thecountryslowlyaccumulatesforeignexchangereserves,which reachjustoverfourmonthsofimportsinthelongrun.Finally,foodimportsasashareofGDP stabilisecloseto4%ofGDPintheBAUscenarioandpercapitaincome,measuredin2017 Euros,risessteadilyto6000Euros.

Figure 5 summarisesthemainpropagationmechanismsfollowingacontinuousdecline inagriculturalproductionduetoclimatechange.Becauseweassumeaconstantrate ofproductivitygrowthintheagriculturalsector,inlinewiththerestoftheeconomy,falling agriculturalproductionleadstoandecreaseinemploymentintheagriculturalandprocessed foodsector,whichreduceshouseholdincome.Thisfallinhouseholdincomeleadstoafallin overallrealconsumption.However,thedynamicsofrealconsumptionoffood,processed foodandnon-foodgoodsisambiguousduetothelinearexpenditurespecificationofthe consumptionallocationdecision.Ontheonehand,lowerrealconsumptionlevelsunder RCP8.5leadtohighermarginalbudgetsharesoffoodandprocessedfoodandalower marginalshareofnon-foodgoodsinconsumption.Ontheotherhand,realconsumption offoodandprocessedfoodfallsbecausepriceinflationforthesegoodsishigherthanfor non-foodgoodsunderRCP8.5duetothehighcostofimportedfood.Asaresult,theoverall impactonrealconsumptionofnon-foodgoodsdependsonthemagnitudeoftheseeffects. Inoursimulations,thismechanismhasanoverallpositiveimpactontherealconsumption demandfornon-foodgoodsundertheRCPHIscenario(butnotRCPLI),mitigatingthenegative impactoflowerhouseholdincomes.However,withhigherfoodprices,theoverallshareof agro/processedfoodproductsinthehouseholdconsumptionbasketishigherunderboth RCPLIandRCPHIscenarios,despitelowerrealconsumptiondemandforthesegoods.In otherwords,householdsconsumelessfoodandspendahigherproportionoftheirtotal consumptionexpenditureduetoclimatechange.

Loweragriculturalproductionandthegrowingdemandforagriculturalandprocessedfood commoditiesalsopushagriculturalimportsaboveBAUlevels,whicharemuchhigherin

Figure5:TransmissionofLossofAgriculturalProduction

Figure5:TransmissionofLossofAgriculturalProduction

nominaltermsinRCPHIwithelevatedglobalfoodpriceinflation.Demandforforeignexchange isalsohigherwithahighertradedeficitdrivenbyfoodimports,andgivenourassumptionthat thegovernmentborrowsafixedproportionofthetradedeficitinforeignexchange,partofthis additionaldemandforforeignexchangeismetbypublicsectorforeignexchangeborrowing. However,thenominalexchangeratestilldepreciatesfasterthanintheBAU,pushingup inflation.

Risinginflationhasseveraleffectsontheeconomy.Ontheonehand,higherinflationpushes

uppolicyrates,pushinguprealdepositratesandlendingratesindomesticcurrency.While higherrealdepositratesreducethemarginalpropensitytoconsume,leadingtoafurther declineinconsumptiondemand,higherdebtfinancingcostsreducetherateofprofit,leading tolowerinvestment.Ontheotherhand,duetotheimperfectpass-throughofnominal exchangeratestodomesticinflation,therealexchangeratedepreciatesmorerelativeto BAU,reducingthepropensitytoimportnon-foodgoodsandtriggeringhigherexportdemand fornon-foodgoods.Theoverallimpactondemandfornon-foodgoodsisthusdetermined bythemagnitudeoftheseeffectsonconsumption,investmentandexports.Althoughinour simulationsthepositiveeffectofhigherexportdemandoutweighsthenegativeeffectson consumptionandinvestmentunderRCPLIandnon-foodproducersemployaslightlyhigher percentageofthelabourforcethanintheBAU,thisadditionalemploymentinthenon-food sectorisfarfromcompensatingforthedeclineinemploymentinagricultureandprocessed food,andtheoverallunemploymentraterisessignificantly 13 .

Whilerealdepreciation-inducedexportgrowthmitigateshigherunemploymentasmentioned above,rapidnominalexchangeratedepreciationhasevenmoreseriousconsequencesfor theexternalpositionandfiscalbalancesbothbypushingupthealreadyhighexternaldebt-toGDPratioandbyincreasingcountryriskandthustheassociatedfinancialacceleratoreffects. Highercountryriskraisesforeignexchangeborrowingratesforboththegovernmentand firms,whileatthesametimeleadingtogreaterrationingofNFCsbyinternationalmarketsand reducingthesupplyofforeignexchange.Theincomeaccountdeterioratesasaresult,putting furtherpressureonanacceleratingcurrentaccountdeficitanderodingforeignexchange reserves.14 Combinedwithhigheroverallunemployment,lowergrowth,lowertaxrevenues andhigherborrowingrates,thegovernment’soverallfinancingneedssoar,pushinguppublic debtfurther.

ThedynamicsoftheeconomyunderfallingagriculturaloutputareshowninFigure6,together withtheBAU,toillustratethemagnitudeoftheseeffects.Clearly,theeffectsoflossof agriculturaloutputareverysevereontheTunisianeconomy,whetherglobalfoodinflation remainslowornot.However,asexpected,theconsequencesaremuchdirerifglobalfood pricesincreaserapidlyinthenextthreedecades.UndertheRCPHIscenario,unemployment exceeds17%inthelongrun,withbothfoodandprocessedfoodimportsmovingtowards two-digitlevelsinthelong-run.Tradedeficitexplodesabove13%,drivenbyhighlevelof foodimports.Similarly,currentaccountdeficitsetsonanunsustainablepath,asthecountry runstheriskofaloomingcurrencycrisiswithadepletionofFXreserves.Publicdeficitand publicdebtlevelsindicaterisingpossibilityofadefaultonpublicdebt,asdebttoGDPratio exceeds140%inthelong-run,withnosignofstabilizing 15.Percapitaincome,measuredin 2017Euros,barelygrowsuntil2050.Inshort,allelseequal,no-actionagainstclimatechange pavesthewayforanalmostcertaineconomiccrisisforTunisiaunderrapidlyrisingglobal foodprices.

Next,wesimulatetwodifferentadaptationpolicyscenariosenvisagedbytheTunisian governmentandoutlinedinthe’Water2050Plan’(Jeffetal.,2020).Whilethisplanincludes severaldifferentadaptationscenarios,wechosetosimulatetwoofthem,namelythe ReinforcedTendencyScenario(RTS)andtheWaterandDevelopmentScenarios(WDS). Table6summarisesthemainassumptionsbehindthesescenarios.IntheRTS,economic growthremainsaroundits2018valueat2.5%.Similarly,thewaterelasticitiesofproductionin

13UndertheRCPHIScenario,employmentinthenon-foodsectoralsofallsbelowtheBAUlevels.

14NotethatwehavenotimposedanyrationingofgovernmentFXborrowing,andthehigherFXdemandcausedby highertradedeficitsispartlymetbygovernmentFXborrowing,asthegovernmentborrowsafixedproportionofthe tradedeficitinFX.

15NotethatwehavenotassumedanyrationingonpublicFXborrowingtoshowtheimplicationsofclimatechange onpublicfinancesclearly.Withsuchelevateddebtlevels,thepublicsectormayfacehighrationinginFX-borrowing, causingacurrencycrash

manufacturingandservicesremainattheirobservedvaluesin2020,whilewaterelasticity ofagriculturalproductionisassumedtofallto0.2.Insuchacase,agriculturalproduction canonlygrowby1%peryear,despiteastrongadaptationinvestmentplantoincreasewater resources,astheavailablewatersupplyismainlyconsumedbytheindustrialandservice sectorsandthuscannotsupportahigheragriculturalgrowthrate.IntheWDSscenario,onthe otherhand,amuchmoreefficientwaterusestrategyinthesesectorssignificantlyreduces thewaterelasticitiesofproductioninallsectors,allowingagriculturalproductiontogrowby 3.5%peryear,alongsideanoveralleconomicgrowthrateof4.3%peryear 16 .

InlinewiththeWater2050plan,weassumethatpublicandprivateadaptationinvestments areboth1.1%ofGDP,andthatpublicinvestmenthasaveryhighimportpropensityof60%,as itinvolvestheconstructionofdesalinationandwastewatermanagementplants,someof whichwillbesolar-powered.Itisalsoassumedthatthepublicadaptationinvestmentwillbe financedbyforeignexchangeloansatafixedrateof1.7%,whichistheinterestrateontheloan fortheSfaxdesalinationplantcurrentlyunderconstruction(JapanInternationalCooperation Agency,2017).Inourmodel,themedium-andlong-termgrowthrateoftheeconomydepends strictlyonthegrowthrateoflabourproductivity.Thus,toachievethehighgrowthrate envisagedintheWDS,weassumethatpublicinvestmentgrowsatamuchhigherratethan inpreviousscenarios,at4.5%,andthatefficientinvestmentinareassuchasinfrastructure, health,R&Dandeducationgraduallyraisesthegrowthrateoflabourproductivitytoover threepercentperyearby2050.Thisisinlinewiththeendogenousgrowthliterature,as detailedinAgenorandYilmaz(2012,2016),andobservedbytheIMF(XiaoandLe,2019).

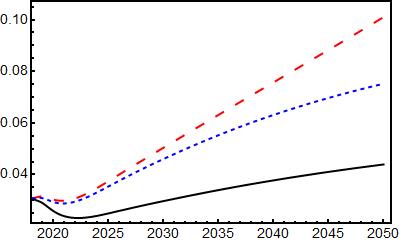

Figure7showstheresultsofthesimulationsforBAU,RCPHI,RTSandWDS.17 Thegradualincreaseinlabourproductivity,drivenbypublicinvestment,andtherapidgrowthinagricultural productionhavesignificantpositiveeffectsonmacroeconomicdynamics,despitethehigh levelofadaptationinvestmentandthehighimportpropensityundertheWDS.Unemployment

16Theadaptationplandoesnotspecifythegrowthofagriculturalgoodsforconsumption,intermediateconsumption orexports.Thus,inoursimulations,wesetthegrowthrateoftheseequaltothegeneralgrowthrateofagricultural productionundereachadaptationscenario.

17InordertoensurethattheshareofagriculturalemploymentremainswithinreasonablelimitsundertheWDS scenario,weassumethatlabourproductivitygrowthintheagriculturalsectorisequaltothegrowthrateofagricultural outputat3.5%.

fallssteadilyto6%by2050andgeneralconsumerpriceinflationisbroughtdowntobelow theBAUlevels,around4%18.Similarly,processedfoodpriceinflationremainsjustbelowto BAUscenario,slightlyabovegeneralinflationwhileagriculturalgoodsinflationislowertha baselinethroughoutthesimulationperiod.Economicgrowthinitiallyfluctuates(drivenby 18Borio(2014)proposesadistinctionbetweennon-inflationary(potential)outputandsustainableoutput,thelatter dependingonsystemicmacro-financialdevelopmentsandexternalimbalances.Ourmodelsimulationssupport thismodellingfeature.

theexport-ledgrowth,asdiscussedabove)tosettleat4.2%,inlinewiththeWDSprojections. Exportsgrowstronglyduetohighproductivitygrowth,andimportsofintermediateandcapital goodsfallsteadily,improvingthetradebalancetoaround7%ofGDP.Theincomeaccount alsoimprovesslightly,leadingtoacurrentaccountdeficitjustbelow7%inthelongterm.19 Afteraslightdeclineinthefirstdecade,foreignexchangereservesasashareofimportsare setonanincreasingpathtowardssustainablelevelsinthelongterm.20 Despitetheincrease inforeigncurrencyloanstofinanceadaptationinvestment,thetotalforeigncurrencydebtto-GDPratioissetonadecliningpathafterinitiallyrising,fallingbelowBAUlevelstojust under60%inthelongrun,therebyreducingcountryriskandinterestratesonpublicforeign currencyborrowingandeliminatingtheunsustainableaccumulationofforeigndebtinRCPHI. Hightaxrevenuesandlowunemploymentleadtoasustaineddeclineinthepublicsector deficitto3.5%andinthepublicdebt/GDPratioto70%inthelongrun.Percapitaincome, measuredin2017Euros,risesrapidlyto9000Eurosby2050asfoodimportsfallbelowtwoper centofGDP,movingTunisiamuchclosertonear-totalfoodsecurity.

TheRTS,ontheotherhand,paintsaverydifferentpicture.Whilethepositivemultipliereffects ofpublicandprivateadaptationpoliciesreduceunemploymentbelowtheBAUlevel,the currencydepreciatessharplycomparedtoallotherscenarios,keepinggeneral,foodand processedfoodinflationclosetothehighinflationscenario.Despitethepositiveimpactof therealdepreciationonnon-foodtrade,lowoverallproductivitygrowth,highimportcostsof adaptationpoliciesandincreasedfoodimportcostsduetoadepreciatedcurrencyleadtoa tradedeficitoftwelvepercent.Coupledwithanexplodingincomeaccountdeficit,thecurrent accountdeficitreacheselevenpercentofGDPandforeignexchangereservesasashareof importsfallbelowtheRCPHIlevelsinthelongrun.Countryriskalsoexplodestolevelsabove RCPHI,bringingforthamuchhigherprobablityofrationingonpublicFXborrowing.Duetothe sluggishgrowthrateoftheeconomy,publicadaptationinvestmentputsstrongpressureon thebudgetdeficitandpublicdebt,astotaldebtfirstexceedsthehighinflationscenariolevel andstabilizesinthelongrunataroundthesamelevel,withexcessiveexternaldebtdriving theincrease.PercapitaincomegrowthalsoslowsdowntoRCPHIlevels,aggravatedbythe rapiddepreciationofthenominalexchangerate.

ClimatechangewillputsignificantpressureonagriculturalproductionlevelsinTunisia, reducingbothproductionfordomesticconsumptionandthetwomainexportcommodities, olivesanddates.Thecostsofnoactionaresevereinmacroeconomicterms,andtheNFC sectorcannotcompensateforthelossesinruralemploymentandproductionifproductivity growthremainssluggishrelativetotherestoftheworld.Theresultisexcessivefiscaland currentaccountdeficits,leadingtounsustainablepublic/externalbalancesandalooming currencycrisis,especiallyifpublicfinancingofexternaldeficitsthroughFXborrowingdriesup inthefaceofelevatedcountryrisk.Theaccumulationofsuchmacroeconomicimbalances

19WehaveassumedthatFDIremainsafixedpercentageofNFCsectorproductionthroughoutthesimulations. Wepartlyunderestimatetheseinflows,asthefavourableeconomicconditionsunderthishigh-growthregimemay triggeranincreaseinFDIinthemediumandlongterm,leadingtoafurtherimprovementinthecurrentaccount.

20Throughthesesimulations,wekepttheratioofpublicFXborrowingtotradedeficitconstant,despiteafalling tradedeficit/GDPratio.Inessence,thereisaconstantneedforcoordinatedmonetaryandfiscalpoliciestoprevent currencyappreciationandensureFXreserveaccumulationandpublicsolvency.Asisthecaseforalldeveloping economies,realcurrencydepreciationinducedbycentralbankinterventioninforeignexchangemarketsmayreduce tradedeficitsatthecostofreducingpercapitaincomeinFX.However,thepositivetradeeffectsofrealdepreciation arelimited,taketimetomaterialiseandareconstrainedbyproductivitygrowthdifferentials,thecomplexityof exportsandthesizeofthetradablesector.Ontheotherhand,depreciationimmediatelyincreasesthedomestic currencyvalueofpublicandprivateFXdebt,increasingcountryriskandthelikelihoodofpublic/privatesector insolvency.WhilepublicFXborrowingmayprovidetheeconomywithmuch-neededFXreserves,increasesinpublic debthaveadestabilisingfinancialacceleratoreffectthroughdomesticandFXbondinterestrates,subsequently worseningtheincomeaccountandleadingtogreaterrationingofcross-borderborrowingbyfirmsorthegovernment. Theseconsiderationscallformuchmoresophisticatedcoordinationbetweenmonetaryandfiscalpolicytoensure sustainabledevelopmentthanthesimpleborrowingrulesweusedinourmodel.

willbeexacerbatedifglobalfoodinflationishigherthangeneralglobalinflationorifTunisia’s exportpartnersgrowslowlyinthecomingdecades.

Whilepolicymakershaverecognisedtheseverityoftheproblemandhaveformulatedlongtermadaptationstrategiesthatincludeinvestmentsinwatersupply,reducinglossesin thedistributionprocessandrehabilitatingexistingreservoirs,thesestrategiesarecostly andrequiretheparticipationoftheprivatesectorintheprocessalongsidethepublic sector.Inaddition,increasingwatersupplyrequirestheconstructionofdesalinationand wastewatertreatmentplants,aswellasenergyresourcestopowertheseunits,whichin thecountry’scurrenteconomicstructurerequireimport-intensiveinvestments.Thus,the financingstructureandcostsofadaptationpoliciesplayacentralroleindeterminingtheir overalleconomicimpactandeffectivenessinstabilisingtheeconomyinthelongrun.

Evenwiththeplannedincreasesinwatersupply,thesimultaneousachievementofwater securityandeconomicdevelopmentwillrequiresignificantreductionsinthewaterelasticity ofproductioninagriculture,industryandservicesthroughtheadoptionofwater-efficient productiontechniques.Theseimprovementsshouldalsobeaccompaniedbyrapidgrowth ineconomy-wideproductivitylevels.Efficientpublicinvestmentinalargepusheffortto stimulatethisproductivitygrowthisthereforecrucial.Ourresultsshowthateconomic developmentandwatersecurityarenotorthogonalifsuchproductivity-enhancingpublic policiesareimplementedtogetherwithwater-efficientproductionmethodsandadaptation measures.

Abid,L.,Quertani,M.,and Zouari-Ghorbel,S.(2014). Macroeconomicandbankspecificdeterminants ofhousehold’snonperformingloansintunisia: Adynamicpaneldata. ProcediaEconomicsand Finance,13:58–68.

Agenor,P.-R.andYilmaz, D. (2012).Aidallocation, growthandwelfarewith productivepublicgoods. InternationalJournalofFinanceandEconomics

Agenor,P.-R.andYilmaz, D. (2016).Thesimpledynamicsofpublicdebtwith productivepublicgoods. MacroeconomicDynamics,pages1–37.

BankforInternationalSettlements(2017).High-level summaryofbaseliiireforms.

Bernanke,B.andGertler, M.(1995).Insidetheblack box:thecreditchannelof monetarypolicytransmission. JournalofEconomic Perspectives,9(4):27–48.

Blecker,R. (2016).The debateover‘thirlwall’slaw’: balance-of-paymentsconstrainedgrowth reconsidered*. European JournalofEconomics andEconomicPolicies: Intervention,133:275–290.

Bogmans,C.,Pescatori, A.,andPrifti,E. (2021).

Fourfactsabout soaringconsumer foodprices. https: //www imf org/en/Blogs/ Articles/2021/06/24/ four-facts-about-soaringconsumer-food-prices. Accessed:2023-04-05.

Borio,C. (2014).Thefi-

nancialcycleandmacroeconomics:Whathavewe learnt? JournalofBanking Finance,45.

Borio,C.andDisyatat,P. (2011).Globalimbalances andthefinancialcrisis:Link ornolink? BISWorking Papers,346.

Borio,C.andDisyatat,P. (2015).Capitalflowsand thecurrentaccount:Takingfinancing(more)seriously. BISWorkingPapers, 525.

Bovari,E.,Giraud,G.,and McIsaac,F. (2018).Copingwithcollapse:Astockflowconsistentmonetary macrodynamicsofglobal warming. EcologicalEconomics,147:383–398.

Brahmi,N.,Dhieb,M.,and Rabia,M.C. (2018).Impactsdel‘élévationdu niveaudelamersurl’évolutionfutured’unecôte basseàlagunedelapéninsuleducapbon(nord-est delatunisie):approche cartographique.In ProceedingsoftheICA,volume1,page14.

CentralBankofTunisia (2019).Annualreporton bankingsupervision.

Charpe,M.,Chiarell,C., Flaschel,P.,andSemmler, W.(2011). FinancialAssets, DebtandLiquidityCrises Springer.

Chebbi,H.E.,Pellissier,J.P.,Khechimi,W.,andRolland,J.-P.(2019). Rapport desynthèsesurl’agricultureenTunisie.PhDthesis, CIHEAM-IAMM.

Chiarella,C.andFlaschel, P. (2006). TheDynamicsofKeynesianMonetaryGrowth:Macrofounda-

tions.CambridgeUniversityPress.

Chiarella,C.,Flaschel,P., andSemmler,W. (2012). ReconstrutingKeynesian MacroeconomicsVolume 1.Springer.

Chiarella,C.,Flaschel,P., andSemmler,W. (2013). ReconstrutingKeynesian MacroeconomicsVolume 2.Springer.

Climat-c (2020).Portailclimatiquedel’institut nationaldelamètèorologie. https://climat-c tn/ INM/web/

Dafermos,Y.,Nikolaidi, M.,andGalanis, G. (2017).Astockflow-fundecological macroeconomicmodel. EcologicalEconomics, 131:191–207.

Dafermos,Y.,Nikolaidi, M.,andGalanis,G.(2018). Climatechange,financial stabilityandmonetary policy. Ecological Economics,152:219–234.

Deandreis,C.,Pommier, D.,Jamila,B.S.,Tounsi, K.,Jouli,M.,Balaghi, R.,Zitouna-Chebbi,R., andSimonet,S. (2021). Impactsdeseffetsdu changementclimatique surlasècuritèalimentaire.

Dhaouadi,L.,Boughdiri, A.,Daghari,I.,Slim,S., BenMaachia,S.,Mkadmic, C.,etal. (2017).Localised irrigationperformancein adatepalmorchardin theoasesofdeguache. JournalofNewSciences, 42:2268–2277.

Fischer,G.,Nachtergaele, F.O.,vanVelthuizen,H., Chiozza,F.,Francheschini, G.,Henry,M.,Muchoney, D.,andTramberend,

S. (2021).Globalagroecologicalzones(gaezv4)modeldocumentation.

Flaschel,P. (2008). The MacrodynamicsofCapitalism.Springer.

Flaschel,P.,Groh,G., Proano,C.,andSemmler, W. (2008). Topicsin AppliedMacrodynamic Theory.Springer.

FoodandoftheUnitedNations,A.O. (2018). Future ofFoodandAgriculture 2018:AlternativePathways to2050.FoodandAgricultureOrganisationofthe UnitedNations.

FoodandAgriculture OrganizationoftheUnited Nations (2018).Foodand agricultureprojectionsto 2050. http://www fao org/ global-perspectivesstudies/food-agriculture\projections-to-2050/en/.

Frankel,J. (2010).Monetarypolicyinemerging markets:Asurvey.technicalreport. NationalBureau ofEconomicResearch

Hansen,N.andAuger,A. (2011).Cma-es:evolutionstrategiesandcovariancematrixadaptation.In Proceedingsofthe13th annualconferencecompaniononGeneticand evolutionarycomputation, pages991–1010.

Ho,M.,Britz,W.,Delzeit, R.,Leblanc,F.,Roson, R.,Schuenemann,F., andWeitzel,M. (2020). Modellingconsumption andconstructinglongtermbaselinesinfinal demand. Journalof GlobalEconomicAnalysis, 5(1):63–108.

IMF (2019).Fifthreview undertheextendedfund

facility,andrequestsfor waiversofnonobservance andmodificationofperformancecriteria,andfor rephasingofaccess.

IPCC,A. (2014).Ipcc fifthassessment report—synthesisreport.

Issam,D.,Hedi,D., BenKhalifa,N.,and Mahmoud,M. (2022). Salineirrigation managementinfield conditionsofasemi-arid areaintunisia. Asian JournalofAgriculture,6(2).

Jacques,P.,Delannoy, L.,Andrieu,B.,Yilmaz,D., Jeanmart,H.,andGodin, A. (2023).Assessingthe economicconsequences ofanenergytransition throughabiophysical stock-flowconsistent model. Ecological Economics,209:107832.

JapanInternational CooperationAgency (2017).Signingofjapanese odaloanagreementwith tunisia:Contributing toasolutiontothe watershortageina majormetropolitanarea withthesecondlargest cityintunisiathroughthe constructionofseawater desalinationfacilities. https://www2 jica go jp/ yen_loan/pdf/en/6851/ 20170718_01 pdf.Accessed: 2023-04-05.

Jeff,Peter,D.J.,and Williams,R. (2020). Elaborationdelavisionet delastratègiedusecteur delèauàl’horizon2050 pourlatunisie:Réalisation desetudesprospectives multitheèmatiques etetablissementde modeèlespreèvisionnels offre-demande(bilans).

Kaminsky,G.,Lizondo,S., andReinhart,C. (1997). Leadingindicatorsofcurrencycrises. IMFWorking Paper,97/79.

Khawla,K.and Mohamed,H. (2020). Hydrogeochemical assessmentof groundwaterquality ingreenhouseintensive agriculturalareasin coastalzoneoftunisia: Caseofteboulba region. Groundwaterfor sustainabledevelopment, 10:100335.

Lluch,C. (1973).Theextendedlinearexpenditure system. EuropeanEconomicReview,4(1):21–32.

Louati,D.,Majdoub,R., Rigane,H.,andAbida,H. (2018).Effectsofirrigatingwithsalinewateron soilsalinization(eastern tunisia). ArabianJournal forScienceandEngineering,43:3793–3805.

McLeay,M.,Radia,A.,and Thomas,R.(2014).Money creationinthemodern economy. BankofEngland quarterlybulletin,pageQ1. MedECC (2021).Les risqueslièsaux changementsclimatiques etenvironnementauxdans larègionmèditerrannèe.

Messai,A.andJouini, F. (2013).Microand macrodeterminantsof non-performingloans. InternationalJournalof EconomicsandFinancial Issues,3(4):852–860.

MinistryofAgriculture, WaterResourcesand FisheriesofTunisia(2020). Rapportnationalsurle secteurdel’eau.

Nucifora,A.,Rijkers,B.,

andFunck,B. (2014).The unfinishedrevolution: bringingopportunity,good jobsandgreaterwealthto alltunisians. Development PolicyReview,Publisher: TheWorldBank

Romdhane,S.andKenzari, K. (2020).Thedeterminantsofthevolatilityof non-performingloansof tunisianbanks:Revolution versuscovid-19. Review ofEconomicsandFinance, 18:92–111.

UnitedNationsClimate Change (2022). Stratègie

dedèveloppementneutre encarbonneetrèsilientau changementclimatique àl’horizon2050-Tunisie. UnitedNationsClimate Change).

WRI (2020).Aqueduct 3.0countryrankings. https://www.wri.org/ applications/aqueduct/ country-rankings/

Xiao,Y.andLe,N.-P. (2019).Estimatingthe stockofpubliccapital in170countries. https: //www.imf.org/external/ np/fad/publicinvestment/

pdf/csupdate_aug19 pdf Accessed:2023-04-05.

Yilmaz,D.andGodin, A. (2020).Modelling smallopendeveloping economiesina financialisedworld:A stock-flowconsistent prototypegrowthmodel. AFDResearchPapers,125.

Zezza,G.andZezza,F. (2019).Onthedesign ofempiricalstock-flowconsistentmodels. Levy EconomicsInstituteof BardColleWorkingPaper, 919.

Realdomesticagriculturalproduction (Y P,A , 1) issplitinthreecomponents:realagricultural productionfordomestichouseholdconsumption (Y P,A C ),forintermediateinputconsumption byothersectors (Y P,A IC ),andforexports (Y P,A W ).Allthreecomponentsofagriculturalproduction aredeterminedbyclimaticconditionsaswementionedaboveandarethereforeexogenous tothemodel.21

Asexplainedinthemaintext,weuseAdapt’ActionandFAOmodelsinordertoprojectthe productionlevelsofthesegoodsinoursimulationperiod.Wethensmooththeproduction pathsandcalculateconstantgrowthratesforeachcategoryofagriculturalproduction:

Aggregaterealdomesticdemandforagriculturalgoods (Y D,A , 5) iscomposedofreal consumptiondemand (Y D,A C , 6) fromhouseholds (CA) andrealintermediateconsumption demand (Y D,A IC , 7) fromprocessedfood (ICA PF ),NFCsectors (ICA NF ),theagriculturalsector (ICA A ) andthegovernmentsector (ICA G ).Weassumethatthedemandforexportsalways matchessupplyandthusrealexportsofagriculturalgoods (X A , 8) aregivenbytheexogenous supply (Y P,A W )

Inordertoproduce,theagriculturesectorusesintermediateinputsfromitsownproduction (ICA A ) ,fromprocessedfoodsector(ICPF A ) andfromothernon-foodsector (ICNF A ).The demandforthesegoodsinrealtermsaregivenbyfixedinput-outputcoefficients αA A,αPF A and αNF A .

Inwhatfollows,theproducersectorisdenotedwithasuperscriptandthedemandingsectorwithasubscript.

Giventheconsumptiondemandbyhouseholdsandintermediateconsumptiondemand fromallsectors,theexcessdemandinagriculturesectorismetbyimportsfromtherestof theworld.Thus,importsofagriculturalconsumption (IM A C ) andintermediateconsumption (IM A IC ) aregivenby:

Theremainingnon-financialsectorsaredividedintotwosectors;aprocessedfoodindustry, denotedas PF ,andasectorthatproducesallprivatenon-foodgoodsandnon-financial servicesintheeconomy,denotedas NF .Processedfoodissoldtohouseholdsforconsumption (CPF ),exportedtotherestoftheworld (X PF ) anddemandedasintermediate consumptionbytheagricultural (ICPF A ),processedfood,(ICPF PF ),non-food(ICPF NF )andthe governmentsectors(ICPF G ).Similarly,thehomogeneousgoodproducedbythenon-food secrtorisdemandedforconsumptionbyhouseholds (CNF ),andintermediateconsumption byallsectorsincludingbanks (IC

).Wefurtherassumethatthis isthecapitalgoodoftheeconomy,purchasedforinvestmentbythenon-financialsector itself(processedfoodandnon-foodNFCsector, I NF F ),households(I NF H )andthegovernment (I NF G ),andexportedtotherestoftheworld(X NF ).Thustherealaggregatedemand(net ofimports)fortheoutputoftheprocessedfood(Y D,PF ,15)andtheNFCgood(Y D,NF ,16}) sectorsaregivenby:

,

), j ∈ (PF,NF ) denotetheimportsharesofelementsofaggregate demand,tobedefinedbelowand ICPF and ICNF arerespectivelythetotalintermediate consumptiondemandfortheprocessedfoodandnon-foodsectorgoods,and I NF ( 17) isthetotalcapitalinvestmentintheeconomygivenbythesumofsectoralinvestments ofagriculture(I NF A ),processedfoodandnon-foodNFCs(I NF F ),government(I NF G ),and households(I

H )

.

Asintheagriculturalsector,processedfoodandnon-foodsectorsuseintermediateinputs fromagriculture,processedfoodandnon-foodsectors.Intermediateconsumptiondemand functionsaregivenbythetechnicalcoefficientsandthelevelofproductionofthesesectors (Y P,PF and Y P,NF ).

Forthegovernment,realintermediateconsumptiondemandforfoodandprocessedfood dependsonpublicemployment(N G),whereasintermediateconsumptionofnon-foodsector goodsdependsonpubliccapîtalstock(KG):

Thus,totalintermediateconsumptiondemandforprocessedfoodandnon-foodsectorgoods are:

Thegoodsmarketsarecharacterizedbydisequilibriasuchthataggregatedemandlessof imports(Y D,PF or Y D,NF )isnotnecessarilyequaltototalproduction(Y P,PF , Y P,NF ).Firms formadaptiveexpectationsonrealexpecteddemandforprocessedfood(Y e,PF ,25)andthe NFCgood(Y e,NF ,26):

where αpop isthepopulationgrowthrate,

isthegrowthrateofcapitalstockinthe totalNFCsector,and βPF y and βNF y aretheadjustmentspeedsofexpectationstoexcess demand,specifictoeachmarket.Thus,thetrendrateofgrowthintheprocessedfood

sectorfollowspopulationgrowthrateandthatofthenon-foodNFCsectorfollowscapital accumulation.

Bothprocessedfoodandnon-foodmarketsareindisequilibriumsuchthatproduction(Y P,i) doesnotnecessarilyequaldemand(Y D,i).Themarketdisequilibriumateachpointintimeis clearedbyinventory(dis)accumulationinbothmarkets(V i,27).

Theproductivesectornotonlyproducestomeetexpecteddemand,butalsotoensurethatit hasthedesiredlevelofinventoriesdefinedin(28).Thisproductionforinventoryreplacement isgivenbyanadjustmentequationtothedifferencebetweenthedesiredandtheactual inventorylevelforeachmarket(I i V ,29):

Y P,i , 30)ineachsectoristhenequaltothesumofexpectedreal demandandproductionfordesiredinventoryreplacement.

Employmentinthenonfood(N NF , 31)andprocessedfood(N PF ,32)sectorsaredetermined viaaLeontieffproductionfunction,withsectorallabourproductivitylevelsgivenby aPF and aNF respectively.

Realimportsofprocessedfood(IM PF ,33)andthenon-foodgood(IM NF ,34)dependon thedifferenttime-varyingimportpropensities(σi M,j ,i ∈{PF,NF },j ∈{C,IC,I })outofreal levelsofconsumption,intermediateconsumptionandinvestment.Inaccordancewiththe data,weassumethattheprocessedfoodisnotusedforinvestmentandthusnotimported forthispurpose.

Thecorrespondingnominalimportsofprocessedfood(IM PF N ,35)andtheNFCgood(IM

, 36)aredefinedas:

where pPF,w and pNF,w aretheworldimportpricesofprocessedfoodandnon-foodgood respectivelyand eN isthenominalexchangerate.Thepropensitiestoimportmovetowardsthe targetimportpropensities(σi,Tar M,j ,37),whicharenegativefunctionsofsector-specificrelative prices,importtaxes (τ i M,j ) andtheelasticityofsubstitutionbetweenimportedanddomestic goods( j 1,i).Aswellasrelativeprices,thetargetpropensitiesalsodependonrelativelabour productivityofTunisia (takenastheproductivityinthenon-foodsector, aNF ) withrespectto itstradepartners(aW ),whichcapturesnon-pricedeterminantsoftradecompetitiveness. Thespedofadjustmenttothetargetpropensitiesisgivenby βi M,j in(38)23 .

Processedfoodexports(X PF )dependontheabilityoftheagriculturalsectortoprovidethe necessaryintermediateconsumptionandthereforegrowatanexogenousrategivenby theclimateandadaptationscenarios(39).Exportsofthenon-foodgood(X NF ,40)onthe otherhandaredeterminedbytheexogenousworldGDP(GDP W )andatimevaryingexport propensity(σNF X ),whichdependsonrelativepricesandrelativelabourproductivityasabove: Aswithimportshares,theexportpropensityadjuststoitstargetvalueslowly,witharelaxation speedof 1/βNF X

Thereareseventeendifferentpricesforgoods,theseareeitherdenominatedindomesticor foreigncurrency:

• Producerprice(pi P )foreachproductindomesticcurrency, i ∈{A,PF,NF }

• Consumerpriceforeachproduct(pi C )indomesticcurrency, i ∈{A,PF,NF }

• Intermediateconsumptionpriceforeachproduct(pi IC )indomesticcurrency, i ∈ {A,PF,NF }.

23Aswementionedabove,processedfoodgoodsarenotusedforinvestmentandthus σPF,Tar M,I =0 and σPF M,I =0 Wethusexcludethisvariablefromourlistofvariablesandoursimulations.

• Capitalgoodpricefornon-foodsector(pNF K )indomesticcurrency.

• Importpriceforprocessedfoodandnon-foodsectorgoods(pi,w)inforeigncurrency, i ∈{PF,NF }

• Importpriceforconsumptionandintermediateconsumptiongoodsofagriculturesector (pA,w i ), i ∈{C,IC}

• Exportpriceforeachproduct(pi X )inforeigncurrency, i ∈{A,PF,NF }.

Weassumethatthetwointernationalpricesforimportsandexportsforeachtypeofproduct followexogenouslevelofinflation.Aswementionedabove,foragriculturalgoods,we distinguishbetweeninternationalpricesofconsumptiongoods(pA,w C )andintermediate consumptiongoods(pA,w C ),whileweassumethatthereisasinglepriceinflationconsumption andintermediateconsumptionofprocessedfoodandnon-foodgoods24 .