5 minute read

Assistive technology in the time of Covid-19 – Global Study Calls for Disability-Inclusive Communication and Stakeholder Collaboration

Assistive technology in the time of Covid-19

Global Study Calls for Disability-Inclusive Communication and Stakeholder Collaboration

Dr Natasha Layton1 and Associate Professor Libby Callaway1,2 , 1 Rehabilitation, Ageing and Independent Living (RAIL) Research Centre, School of Primary and Allied Health Care, Monash University, Australia; 2 Occupational Therapy Department, School of Primary and Allied Health Care, Monash University

Millions of people around the world affected by illness, disability or the impacts of ageing rely on assistive technology (AT) to take part in activities that are meaningful to them. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that less than 10 per cent of the global population had access to necessary AT. Even high-income countries like Australia had undermet need, .

What, then, happened to AT users during the Covid-19 global pandemic? The WHO commissioned Monash University’s RAIL Research Centre with the Centre for Inclusive Policy to investigate the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on AT use and provision. This global study employed a team of regional researchers – many with lived experience of AT or disability – across the six WHO global regions (see figure one). Accessible surveys and targeted interviews with nearly 150 AT users, their families and AT providers were conducted for the following reasons:

1. To understand the experience of AT users and providers during Covid-19 2. To identify strategies for AT systems strengthening and pandemic response

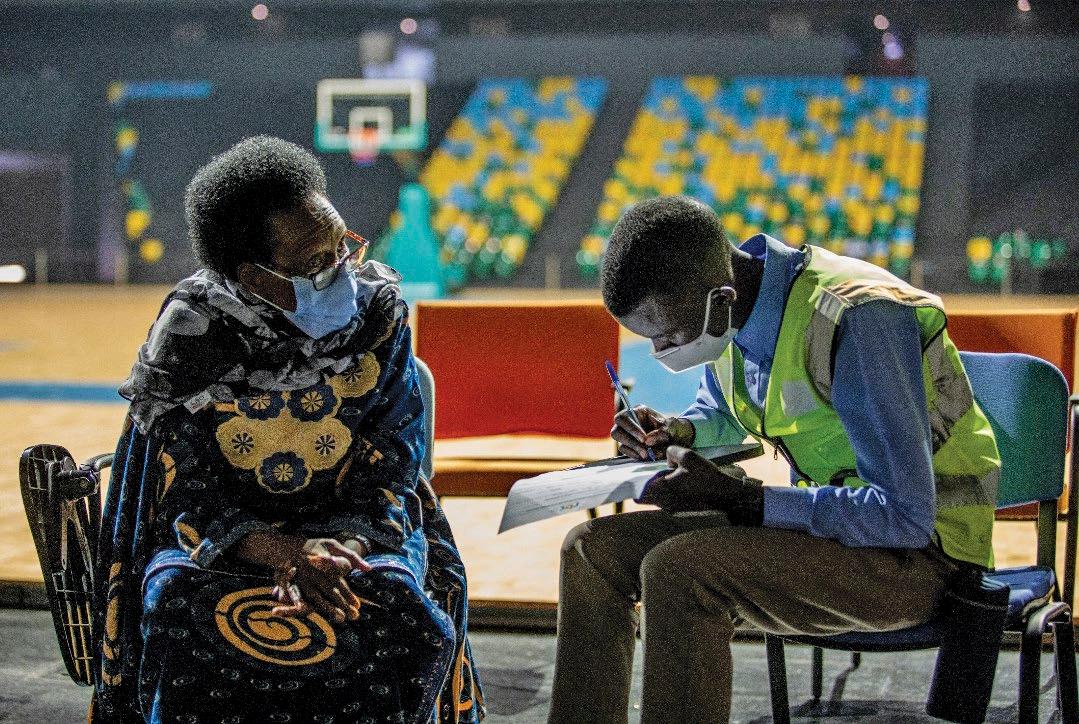

Figure 1: A regional researcher conducts an interview with an AT user.

Findings

The study elicited the following information about a range of enablers and barriers specific to AT access and use:

Communication enablers and barriers AT users, practitioners and suppliers enacted innovative strategies to manage pandemic restrictions and meet AT supply and maintenance needs. Information and communication technologies such as smart phones and reliable internet connectivity enabled AT users to access information, organise remote service delivery, and obtain advice from occupational therapists, other AT advisers and AT suppliers. Civil society (that is, neighbours, local communities and

disabled persons organisations) collaborated to find solutions to the impact of pandemic restrictions. Examples included sharing AT resources, making masks for personal protection when access was lacking or specific designs were needed to enable lip reading, and outreach activities to check on people who might be isolated or vulnerable.

Across regions, AT users were often not included in public health responses. Overall, government policy changes were considered less agile than civil society actions. Important messages like how to avoid virus transmission were not understood, particularly by those living with hearing, vision or cognitive/ communication impairments. Greater disadvantage existed when there was limited access to information and communication technology, internet connectivity or data allowances – as in remote areas.

AT stakeholders voiced a clear need for policy makers to ensure public health messages were accessible to everyone, to consult them on how public health responses might impact AT users, and to recognise information and communication technologies like smart phones as a priority.

Collaboration enablers and barriers AT personnel required infection control training and adequate supplies of personal protective equipment. Stakeholders suggested AT services be integrated into healthcare systems (particularly community or primary health care), that governments guarantee the procurement and supply of quality-assured assistive products, and that a broader range of health personnel be trained and equipped to provide and support AT use to mitigate the impacts of a pandemic. The AT supply network needed to be considered as an essential service in order to stay open, safe and accessible throughout the Covid-19 escalation – however many governments did not see it this way. This posed significant issues for AT access, and individual health, function and participation. When AT services were closed, people lost access to maintenance or advisory services like AT repairs and replacements. Many AT services were not well-prepared for the global health crisis, and were often only available in big cities and not regional or remote areas. Telehealth services were rarely available, and many AT users and providers did not have digital literacy or product/internet access. Some middle to higher-income regions were able to enact rapid policy changes to fund telehealth and the AT required to engage in it, while AT users in lowerincome regions were severely impacted.

Recommendations The following key recommendations were made to inform global public policy and ensure pandemic responses were AT-user inclusive: 1. Make pandemic public health responses inclusive of AT users; 2. Recognise AT products and services as essential during a pandemic or health emergency; and 3. Strengthen AT services, including outreach and telehealth services, to improve preparedness for future pandemic responses.

Study findings and recommendations have been presented at the Second Global Consultation to inform the WHO-UNICEF Global Report on Assistive Technology (to be released in April), used to engage Australian governments and policy makers, and resulted in open access publications which can be found by scanning the QR code below.

A podcast featuring two of the chief investigators is also available by scanning the QR code below.

About the authors Natasha Layton is an occupational therapist whose PhD explored the role of AT and related supports in achieving equal outcomes. She is interested in the nexus between evidence, practice and policy, and has worked clinically and in research, policy and advocacy roles. Natasha is currently a senior research fellow with the Rehabilitation, Ageing and Independent Living (RAIL) Research Centre at Monash University, and an industry adjunct at Swinburne University.

Libby Callaway is a registered occupational therapist and associated professor who works across the Rehabilitation, Ageing and Independent Living (RAIL) Research Centre and Occupational Therapy Department in the School of Primary and Allied Healthcare at Monash University. At Monash, Libby leads a national program of research funded by state and federal governments and focused on housing, technology and workforce co-design. Libby is also the president of the Australian Rehabilitation and Assistive Technology Association and the director of a community-based private practice working with NDIS participants with neurological disabilities.

References can be viewed by scanning the QR code