COMMODORE Simon Currin

VICE COMMODORES

Phil Heaton

Fiona Jones

REAR COMMODORES Zdenka Griswold

Reg Barker

REGIONAL REAR COMMODORES

GREAT BRITAIN Carol Dutton

IRELAND Alex Blackwell

NW EUROPE Hans Hansell

NE USA & ATLANTIC CANADA Janet Garnier & Henry DiPietro

SE USA Doug Selden

W COAST NORTH AMERICA Liza Copeland

CALIFORNIA, MEXICO & HAWAII Jonathan Ganz

NE AUSTRALIA John Hembrow

SE AUSTRALIA Scot Wheelhouse

NEW ZEALAND & SW PACIFIC Viki Moore

SOUTH AFRICA John Franklin

ROVING REAR COMMODORES

Steve Brown, Guy Chester, Thierry Courvoisier, Bill Heaton & Grace Arnison, Lars & Susanne

Hellman, Jurriaan Kloek & Camila De Conto, Stuart & Anne Letton, Pam MacBrayne & Denis Moonan, Simon Phillips, Sarah & Phil Tadd, Rhys Walters, Sue & Andy Warman

PAST COMMODORES

1954-1960 Humphrey Barton

1960-1968 Tim Heywood

1968-1975 Brian Stewart

1975-1982 Peter Carter-Ruck

1982-1988 John Foot

1988-1994 Mary Barton

1994-1998 Tony Vasey

1998-2002 Mike Pocock

2002-2006 Alan Taylor

2006-2009 Martin Thomas

2009-2012 Bill McLaren

2012-2016 John Franklin

..2016-2019 Anne Hammick

SECRETARY Rachelle Turk

Tel: (UK) +44 20 7099 2678

Tel: (USA) +1 844 696 4480

e-mail: secretary@oceancruisingclub.org

EDITOR, FLYING FISH Anne Hammick

e-mail: flying.fish@oceancruisingclub.org

OCC ADVERTISING Details page 248

OCC WEBSITE www.oceancruisingclub.org

The information in this publication is not to be used for navigation. It is largely anecdotal, while the views expressed are those of the individual contributors and are not necessarily shared or endorsed by the OCC or its members. The material in this journal may be inaccurate or out-of-date – you rely upon it at your own risk.

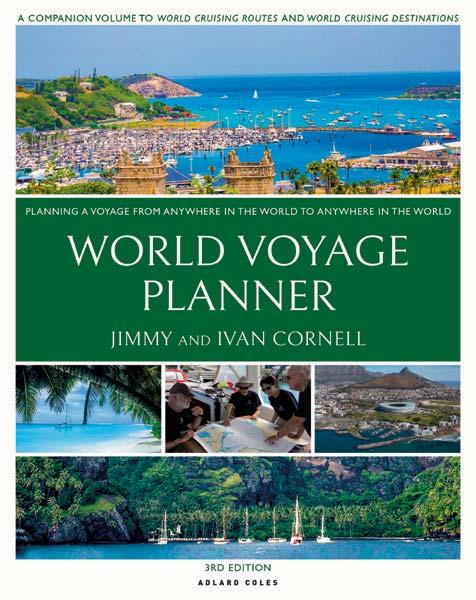

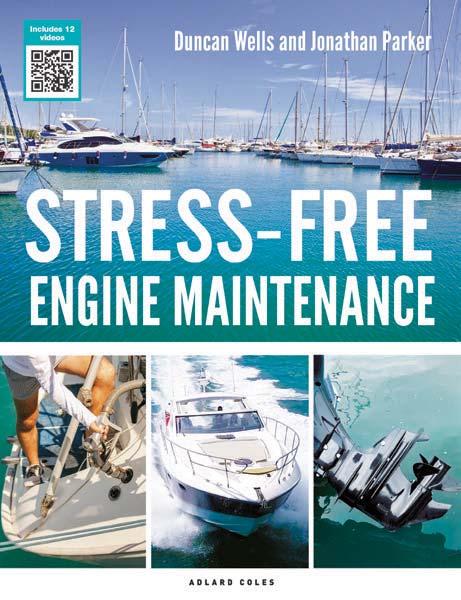

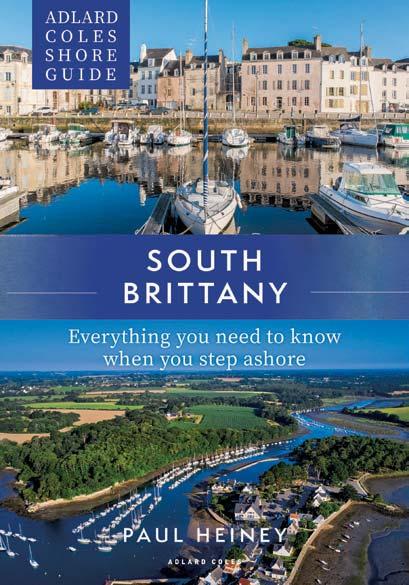

Herewith another fat Fish – overfed, some might say! In its pages you’ll find 16 articles and 11 book reviews in addition to the usual contents and advertiser listings and, sadly, five obituaries.

Regarding advertisements I’d like to thank all our regular advertisers and particularly Mid Atlantic Yacht Services (page 173) who have advertised in every Flying Fish for the past 25 years! I’d also like to draw attention to the Club’s own advertisements –for our Platinum Anniversary (page 125), the OCC Trust (page 79) and the new and updated UK Regalia advertisement (page 211). The headless model in the previous one has been replaced by a great photo of Vice Commodore Fi Jones outside the RNLI College (notice the lifeboats in the background) taken by John van-Schalkwyk during the AGM weekend. Many thanks to them both!

Now for a few requests. First off, if you’re considering writing for Flying Fish, please read the Sending Submissions instructions which appear on page 210 of this issue. They give practical guidance regarding content, length, illustrations and, most importantly, deadlines! They also includes the sentence, ‘Please tell me if you’re sending the same piece elsewhere, inside or outside the OCC’. There’s good reason for this. While Flying Fish and the Newsletter have never actually run the same article in both publications we’ve come close to it on a couple of occasions ... very embarrassing! Regarding the ‘outside the OCC’ phrase, it’s courteous to credit another club if an article went to them first. More importantly, many commercial magazines impose limitations on how soon an article to which they’ve bought the Rights can be republished. If an article in Flying Fish infringed this, both we and the author would be in trouble.

On a lighter note, the Flying Fish store cupboard is running low on recipes. They don’t always have to be galley-friendly – you’d need a large work surface to produce Frances Griffiths’ delicious Raspberry Roulade featured on page 56 – though some members have boats with galleys to rival the average shoreside kitchen. Others prepare goodies ashore to take to Club events and gatherings. Recipes from outside the UK would be particularly welcome.

Finally, members who don’t visit the OCC website regularly will find some fascinating if sobering reading in the new OCC publication Climate Change and Ocean Cruising, downloadable along with several Good Practice Guides from www.oceancruisingclub. org/OCC-Knowledge (you don’t need to be signed in). Its 27 pages include input from well-known names such as Jimmy Cornell, Frank Singleton, Fred Pickhardt, Sebastian Wache, Jeremy Davis and Bob McDavitt as well as from OCC luminaries.

Oh yes, at risk of being boring, the DEADLINE for submissions to Flying Fish 2023/2 is Sunday 1st October, though the issue may close early if it gets as fat as this one!

The 2023 Annual Dinner and presentation of the 2022 Awards took place on Saturday 15th April at the Royal National Lifeboat Institution College in Poole, the first time since 2019 that it had been held live in the UK. Past Commodore Martin Thomas was Master of Ceremonies, a role he discharged to perfection in front of 101 members, their guests and nonmember Award winners attending as guests of the Club.

All the photographs taken during the presentation ceremony are reproduced courtesy of John vanSchalkwyk. Thanks are also due to Eoin Robson, Chair of the Awards Sub-committee, and his panel of hard-working judges, Daria Blackwell who has handled the Club’s PR for the past ten years, which includes announcing our Award results to the international press, and not least Club Secretary Rachelle Turk for her impeccable organisation of the entire event.

The history and criteria for all the awards, together with information about how to submit a nomination online, will be found at https://www. oceancruisingclub.org/Awards.

Presented by the family of David Wallis, Founding Editor of Flying Fish, and first awarded in 1991, this silver salver recognises the ‘most outstanding, valuable or enjoyable contribution’ to the year’s issues. The winner is decided by vote of the Flying Fish Editorial Sub-committee.

For only the second time in its 33-year history an equal number of votes were cast for two articles, Sailing and Diving the Many Motu by Ellen Massey Leonard, which appeared in Flying Fish 2022/1 and Capsize! by Anthea Cornell Stock from Flying Fish 2022/2. The two articles hcould hardly be more different. Ellen Massey Leonard’s 13-page article is a true ‘feel-good’ piece describing three visits to the Tuamotu Archipelago with her husband Seth over a span of 24 years, illustrated by 16 memorable photographs. Among the comments made by members of the Editorial Sub-committee were: ‘I’d

love to visit the Tuamotus to dive their waters and see their spectacular biodiversity with my own eyes. Ellen describes both the diving and the sailing so well, and the pictures are fabulous’, ‘Ellen’s articles are always well-written and her love, care and enthusiasm for nature (and sailing) are in no doubt’, ‘Beautifully written, evocative of both the experience and the place’ and ‘Slightly out of the normal mould of cruising articles and their boat is drop-dead gorgeous!’.

Ellen was unable to travel from Hawai‘i to accept her award in person, but wrote:

‘I’d like to thank the OCC for the honour of this award. I regret that I’m unable to receive it in person; it would have been wonderful to join you!

I’d particularly like to thank Anne for the incredible work she does every year – twice a year! – in creating Flying Fish. It’s a superb publication, always full of fascinating tales of adventure on the high seas all over the world. I’d also like to thank our Commodore Simon, Vice Commodores Daria and Phil, and all of our club officers and committee members for the hard work they do to make the OCC such a great community and engaging club. It’s always such a good feeling to come into an anchorage and see another flying fish burgee!’

Turn to page 126 of this issue for Close-Hauled to Hawai ‘ i , Ellen’s most recent contribution to Flying Fish.

In contrast, Capsize! by Anthea Cornell Stock covers less than three pages and is without illustrations. Written more than 20 years ago and never intended for publication, it only came to light following Anthea’s death in September last year (her obituary also appears Flying Fish 2022/2). Capsize! tells how she accepted the offer of a berth

from the Azores back to the UK aboard Dazzler, a brand-new 46ft (14m) catamaran owned by a fellow OCC member, and what happened after the yacht capsized under spinnaker 36 hours and several hundred miles into the passage. The seven crew were rescued by a ship some 12 hours later.

As members of the Editorial Sub-committee observed: ‘What an adventure, and what an understated but vivid description of it!’ ‘A short but gripping account of every multihull sailor’s worst nightmare,’ and ‘The experience of being in a capsized catamaran in the Atlantic was clearly not enjoyable but Anthea’s account of it sure was interesting’.

Both articles will be found in the Flying Fish online archive at https://oceancruisingclub.org/ Flying-Fish-Archive.

Presented by Admiral (then Commodore) Mary Barton and first awarded in 1993, the Qualifier’s Mug recognises the most ambitious or arduous qualifying voyage published by a member in print or online, or submitted to the OCC for future publication.

In March 2022 Ainur Mutiyeva and husband Shaun Weaver departed Panama aboard their Gitana 43 Three Ships for Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, more than 8000 miles away. Not so unusual a passage for OCC members perhaps, except that they were not planning to stop even once en route. Also, for Ainur, who comes from landlocked Kazakhstan, this would be her first passage of more than 500 miles. Shaun and Ainur’s account of their passage, entitled Destination PNG, appeared in Flying Fish 2022/2.

In the words of Ainur’s proposer for the Qualifier’s Mug, ‘Their non-stop passage, which took 144 days, was an outstanding example of tenacity and seamanship reflecting the true ethos of the OCC. The fact that this was Ainur’s first experience of a major ocean crossing, and the style, enthusiasm and commitment she demonstrated during the passage were impressive to say the least. Doing 12-hour watches for 43 days while hand-steering for the majority of the time is special enough, but volunteering to do it at night, and her description of what the passage meant to her, encapsulating so profoundly the essence of ocean sailing, makes her a more than worthy candidate for this award’.

Ainur and Shaun are still on the other side of the world, but Ainur (who is multilingual) asked Vice Commodore Fi Jones to read out her words at the Annual Dinner:

‘Good evening everyone. First of all I want to say thank you to Fi for

being there in my place as PNG is a long way off and, of course, thank you for my award and for all the help I received from OCC members, including Chris and Fi Jones, Tom Harris and Brian Hull. It still seems a little surreal that I, as a lady working in the middle of an oilfield in Kazakhstan who is still useless at swimming and had never seen this way of life previously, departed from my home country and have now been presented with this award. My husband Shaunskie is passionate about his sailing and even though he can be really grumpy (but not all the time!) I love what we have done so far.

There were moments when I believed I should just give up, but then the ocean magically gave me another reason to continue. As all of you probably know, it is not very inspirational when you cook dinner in the galley and then the boat rolls and half your dinner ends up behind the stove and the other half on the floor – it just means the old five-second rule and smaller portions... However, when the true majesty of the ocean shows itself with the fish and the birds hunting each other to continue the path and magic of life, what does a bit of curry on the floor matter?

Three Ships felt as if, regardless of our circumstances which on a few occasions were extremely uncomfortable and hard – I refer to the various curries and banged heads and bruised fingers – she was there to keep us safe and keep moving forward. I feel very privileged to have had this experience and indeed I hope to continue. How much floorserved curry that will entail remains to be seen. As for my award, it means a lot to me personally because it was awarded by people of the same mind. Thank you.’

Introduced in 2008, this award is made to one or more OCC Port Officers or Port Officer Representatives who have provided outstanding service to both local and visiting members, as well as to the wider sailing community.

Three Port Officer Service Awards were made for 2022, to Bill & Chris Burry, Port Officers for Deltaville and Mathews, Virginia, USA, Peter Dodd, Port Officer with Terry Folinsbee for Mahone Bay and Lunenberg, Nova Scotia, Canada, and Mike Hodder, Port Officer for Crosshaven, Co Cork in the Republic of Ireland.

Bill & Chris Burry received multiple nominations mentioning how they offer assistance and practical information to members and, when hosting members at their own dock as they do frequently, offer hot showers, laundry facilities, fresh water and lifts to the grocery store. As one of their nominators, a repeat visitor, put it: ‘They go above and beyond to welcome us and share their lives with us. They are more than Port Officers now, they are friends and represent all that is so positive about the cruising community’. Another mentioned how: ‘Even before they were appointed in 2018 Chris and Bill were already offering members one of the best free docks in the area, giving advice regarding local mechanics, allowing parcel deliveries to their address and sharing their considerable knowledge of Chesapeake Bay anchorages and places to visit. Members can count on the Burrys to assist in finding haul-out yards for hurricane season and helping them prepare for offshore passages. Often there are several OCC boats on their dock to whom they offer true ‘southern hospitality’, perhaps with an oyster and crab cook-out to give visitors a taste of local food. They also organise and host the annual Southern Chesapeake Bay Dinner at the Mathews Yacht Club in October. We have been to several of these and they are always enjoyable, interesting evenings and a great way to meet other cruisers’.

Bill and Chris flew over from the US to attend the Annual Dinner and Chris spoke for both of them when they came forward to receive their award:

‘We are delighted to be here in person to accept this award. For the past five years we have been Port Officers for the small towns of Deltaville and Mathews, Virginia on the lower western shore of the Chesapeake Bay, and had been hosting OCC boats at our dock even prior to our appointment. It is a great way to meet fellow long-distance cruisers and

MC Martin Thomas with Chris and Bill Burry, Port Officers for Deltaville and Mathews, Virginia

MC Martin Thomas with Chris and Bill Burry, Port Officers for Deltaville and Mathews, Virginia

we have met numerous sailors this way, many of whom have become life-long friends and are here tonight.

Many of you know that we have a sailing dog named Flaco, an American foxhound who adopted us over ten years ago. We’ve taught him to sail and take him on our long cruises. One cold, dreary morning in January he was up early so I got out of bed to put him outside. When he returned I crawled back into bed and picked up my cell phone to check the morning news. It was a very pleasant surprise to learn from Commodore Simon that we were being recognised with a Port Officer Service Award. We had already made the decision to attend this year’s AGM, combining it with a return transatlantic passage on the Queen Mary 2, and this gives it even more meaning. We are honoured to accept this award and look forward to continuing to welcome you to the southern Chesapeake Bay.’

Peter Dodd, Port Officer with Terry Folinsbee for Mahone Bay and Lunenberg, Nova Scotia, has been in post ‘on the ground’ since 2007 and on the airwaves since 2011. Like many members he learned to sail as a child in dinghies before expanding his horizons over the following 50 years to the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Provinces, including two voyages from Lake Ontario to Nova Scotia. For ten years following retirement in 2002 he spent winters aboard his Whitby 42 Rovinkind II in the Caribbean and summers at his home on Young Island, NS, joining the OCC in 2004. During this time he established an AIS receiving station for Marine Traffic and recently set up another AIS station, of which more below.

As his nominator observed: ‘Port Officer Awards usually relate to the services and assistance provided directly to cruisers and Peter has spent a lot of time doing this. However, he has also been working with the OCC Digital Development Group (DDG) to make a wider contribution to OCC cruisers across the globe and is currently

assisting with the trialling and testing of technology to enhance the accuracy of the OCC Fleet Map.

He has set up an AIS Hub which links with the vessel position updates provided by the Club’s IT contractor to enable more frequent vessel position updates on both the website and the app currently under development. He is also working with the DDG to build a backup service for the Fleet Map, including a server, integration links and an AIS receiver. Peter has been an enthusiastic and proactive user of the Fleet Map to identify cruisers in his area. As well as recognising his direct contribution to our Club, hopefully this award will encourage other Port Officers to follow his lead and so benefit all members visiting a new area.’

Peter was unable to attend the Annual Dinner to receive his Port Officer Service Award in person, but via fellow Nova Scotian John van-Schalkwyk told us:

‘It is with great pleasure that I accept this award – doing what I enjoy doing and being recognised for it is incredibly satisfying. In 2011 there was little AIS coverage in our area of Nova Scotia and, with the support of Marine Traffic, I established the Mahone Bay ground station. Then came Raspberry Pi with a dAISy Hat, which must sound like an exotic dessert! The Raspberry Pi is a single-board computer, the Hat is ‘hardware on top’ and dAISy is ‘Do AIS Yourself’. How could I resist setting up another station?

As long as my station reports positions to AIS Hub I can access all the other data being reported to AIS Hub. The OCC team is taking advantage of this to update the Fleet Map at no extra cost and I have been pleased to help them with this effort. What is work for some is fun for me and I invite anyone who would like to establish an AIS receiving station in a poorly covered area of the globe to contact me for support.

Thank you again.’

Mike Hodder , who has been Port Officer for Crosshaven, Co Cork since 2015, had less distance to cover to reach Poole and we were delighted that he was able to receive his Port Officer Service Award in person. Unlike the other two winners, his nomination focused on a single ‘service’, though just one among many. His American

nominators describe Mike as: ‘A consummate ambassador for the OCC, especially for newcomers to Ireland – a knowledgeable, genial and helpful host by every measure. He responded to our introductory query with a trove of useful written, online and personal references to help us narrow the options about where to make landfall after a passage from North America. As we learned more about potential arrival ports and Mike learned more about our likes and dislikes, he began to provide more specific recommendations, all of which was most welcome of course, but not by itself worthy of an award. However, when I became injured shortly before arrival and before we had even met in person, Mike was quick to help me gain ready access into the Irish Healthcare System. He also offered us the extended use of his family’s cottage in Co Kerry for post-operative convalescence. When we did eventually travel from Co Kerry to Co Cork, Mike and his lovely wife Carol insisted we stay at their house rather than in a hotel or B&B, extending the invitation to our crew as well. Nearly three months after our arrival in his Port Officer area Mike continues to provide us with insightful information to ensure we enjoy the highest quality of life while in Ireland.’

A little way into his acceptance speech Mike gave us his recollection of events, though not before making some Oscar-worthy thanks:

‘Commodore, Flag Officers, General Committee and members, thank you so much for this award. I am a Port Officer in order to help strangers enjoy their visit to a new port, but to be thanked and acknowledged for going the extra mile is very heart warming. First I must thank some important people, including Daria and Alex Blackwell who asked me to organise an OCC dinner and weekend. With their encouragement and support I agreed and the dinner in Kinsale was the best-attended OCC event ever held in Ireland.

I must also thank my nominators, who contacted me early last year, planning to sail to the Azores and on to Ireland, cruise the south coast and then cross to Scotland to meet friends. Their arrival was traumatic to say the least. They intended to make landfall in Dingle on Ireland’s west coast, where we have a son, so I asked him to keep an eye out for them. He replied that he had picked them up on AIS and they were just off

The Skelligs so should be in the next day, but in texts the following day he told me they had not moved much overnight, then that the Valentia Lifeboat had launched and finally that they were being towed into Portmagee. Later that day David phoned to tell me that their engine had broken down, there was no wind, he had a suspected broken finger and when he informed the Coastguard they said there was a storm coming! We got to know them quite well over the next few months, including having them visit. They were extremely grateful for all we did for them and I want to thank them for the very kind and generous letter they wrote to recommend me for this Award. Once again, my thanks to the Commodore and Committee, I am truly delighted.’

First awarded in 1990, the Australian Trophy was donated by Sid Jaffe, twice Rear Commodore Australia. Carved from a solid piece of teak by Wally Brandis, it is awarded for a voyage made by an Australian member or members which starts or finishes in Australia. The winner is selected by past and present Australian Regional Rear Commodores following nomination by the Australian membership.

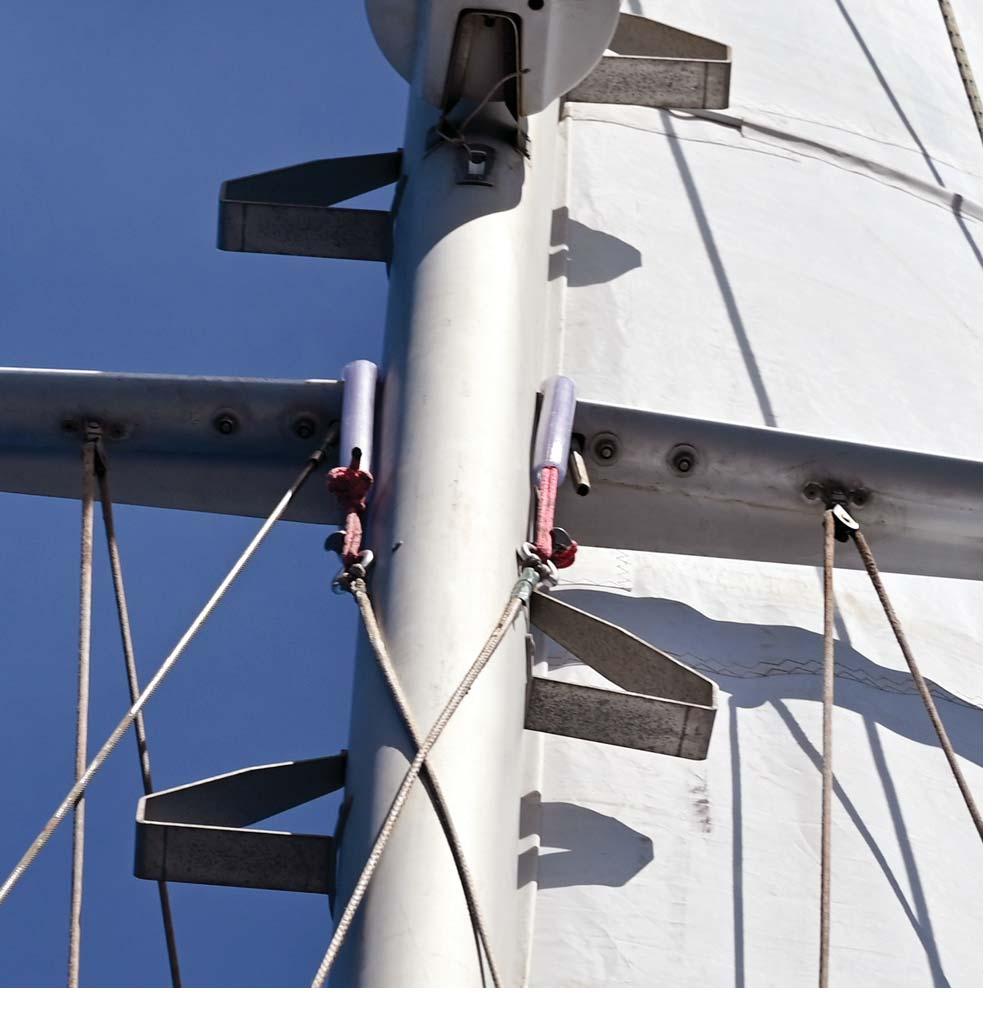

Recipient of the Australian Trophy for 2022 was Roving Rear Commodore Guy Chester, familiar to many members from his reports in recent Newsletters. The Trophy recognises his singlehanded voyage from New Zealand, where he bought his 32-yearold, 52ft (16m) cedar and balsa trimaran Oceans Tribute , to Richards Bay, South Africa. His route took in New Caledonia, Cairns and Darwin in northern Australia, Cocos Keeling, the Indian Ocean and La Réunion Island before finally making landfall at Richards Bay.

Since then Guy has continued – still singlehanded – across the South Atlantic to the Caribbean, reaching Antigua on 2nd January this year. Turn to page 113 of this issue to read his account not just of this passage but of preparing Oceans Tribute for singlehanded ocean passagemaking. At the time of writing (April 2023) Guy was enjoying some fully-crewed racing around the Caribbean, where he plans to stay for the remainder of the season. He is a member of the General Committee as well as Members’ Global Support Network representative for the Indo-Pacific region, and in

2020 was one of the recipients of the OCC Award for his work in assisting the cruising community during Covid. He is also Director of EcoSustainAbility, which provides environmental and sustainable tourism/ecotourism consulting worldwide.

The Vertue Award is presented to a member in North America for an outstanding voyage or for service to the Club. Named after Vertue XXXV, in which OCC Founder Humphrey Barton crossed the North Atlantic in 1950, it was created in 2014 to commemorate the Club’s 60th anniversary. Awardees are selected by North American Regional Rear Commodores.

In 2022 the Vertue Award went to Harriet and TL Linskey , recognising the development and success of their Hands Across the Sea child-literacy programme. They have covered more than 50,000 ocean miles in the past 36 years, including thirteen 3500-mile round trips from their former home in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts to schools in Antigua, Dominica, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada. The boat for their ‘work commute’ was their 46ft (14m) catamaran Hands Across the Sea, now renamed Ocean.

Starting back in 2007, pre-schools, primary schools and high schools in the Eastern Caribbean began benefitting from the creation of Hands Across the Sea lending libraries containing new books sent by Hands and transported to their island and school by cargo ship. Each school library – many run by the students themselves – received a range of books addressing every reading level and every subject, fiction as well as non-fiction.

During the 13 years that Harriet and TL ran the Hands Across the Sea programme it donated more than half a million new books to nearly a thousand schools and pre-schools in the Eastern Caribbean, changing the lives of over 150,000 children as

it opened their eyes to the wider world. In 2021, after making the decision to retire from the organisation, they worked hard to ensure it remained active and Hands Across the Sea continues to thrive even though Harriet and TL have now crossed the Pacific to settle in New Zealand.

Harriet and TL Linskey were presented with their Vertue ‘keeper’ Award last December at the annual Opua Potluck organised by Nina Kiff, Port Officer for Bay of Islands, NZ. In the photograph TL is holding the tiller from OCC founder Humphrey Barton’s Vertue XXXV – most appropriate, bearing in mind the name of the award. Hum’s son Peter had it in his garage and when he was having a clear-out asked Nina, Hum’s great niece, to be its next custodian.

On receiving the Vertue Award Harriet told those present:

‘We first sailed across the Pacific in a 28ft (8∙5m) Bristol Channel Cutter, a bluewater cruiser not much longer than Humphrey Barton’s Vertue XXXV. Back in 1988 the ‘big boats’ were 40-footers. Now boats are much larger, but the needs of local communities are as urgent as before. We are thrilled that Hands carries on and is recognised in the Eastern Caribbean as still having a huge impact.’ TL added: ‘We are honoured to receive the Vertue Award from the OCC. We were honoured also to be welcomed by so many Caribbean school principals and teachers over the years, and to be able to give children a gift that truly lasts a lifetime – the gift of literacy.’

Donated by the Jester Trust as a way to perpetuate the spirit and ideals epitomised by Blondie Hasler and Mike Richey aboard the junk-rigged Folkboat Jester, this award recognises a noteworthy singlehanded voyage or series of voyages made in a vessel of 30ft (9∙1m) or less overall, or a contribution to the art of singlehanded ocean sailing. It was first presented in 2006 and is open to both members and non-members.

Recipient of the OCC Jester Award for 2022 was Cal Currier for his solo Atlantic crossing from Marion, Massachusetts to Lagos, Portugal aboard Argo, his 1976-built Tartan 30. The 3400 mile passage took him 28 days, including a brief stopover in the Azores. This would have been an impressive passage in any circumstances, but was made all the more so because Cal was only 16 at the time. Growing up in Palo Alto, California he had links to the sailing community, but had very limited sailing experience himself, none of it on the ocean. Having set himself the goal of sailing solo across the Atlantic he started to learn seriously, with support from his family as well as from sailmaker and OCC member Sandy Van Zandt who also found him a suitable boat. Only four months later Cal set off.

One of his nominators went out of his way to praise ‘the spirit in which he completed the entire endeavour which, more than his young age, makes his accomplishment notable and worthy of the OCC’s recognition. A few key character traits greatly increased his

chances of success. He was wise enough to enlist the help of his father and grandfather, both experienced ocean sailors, and of sailor, sailmaker and longtime OCC member Sandy Van Zandt. He was humble enough to tackle the trip one step at a time, giving himself permission to not go or to turn back if he wished. And he wanted to do this trip primarily to see whether he could – to prove it to himself, not to followers on social media. In the end Cal made crossing the Atlantic solo look easy. But it was the preparation, the assistance, the confidence tempered with humility that led to his success.’

Cal is still in full-time education so was unable to attend the Annual Dinner to receive the Jester Award in person, but wrote:

‘Thank you to the OCC for giving me this award. I’m very sorry I couldn’t make it to see you in person.

If there’s one thing I learned from my Atlantic trip, it’s to keep it simple and know my limitations. When I started my solo Atlantic campaign I had no thought that I would ever get an award for it. I’m very humbled to be recognised this way, and don’t yet consider myself near to the same category as you all. It was easier to sail across the Atlantic than to convince people to let me do it, but now that I’ve received the Jester Award I’m given more slack, so this is just the beginning. I’m racing dinghies on the West Coast of the US this year and planning to sail Argo from Portugal to Greece in June. Here’s to many great adventures in the future, hopefully with some of you. Keep it simple, keep it safe, keep it going.

With gratitude, Cal Currier’

Donated by past Commodore Tony Vasey and his wife Jill, and first awarded in 1997, this handsome trophy recognises an unusual or exploratory voyage made by an OCC member or members.

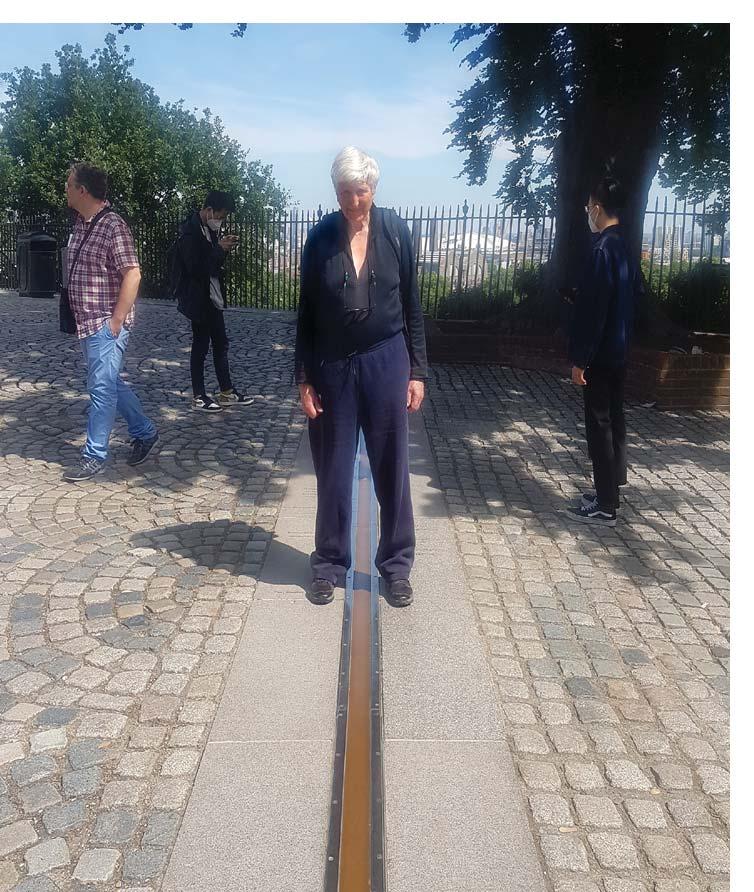

Since being appointed Roving Rear Commodores in September 2021, Lars and Susanne Hellman have been contributing fascinating articles to the Newsletter describing a variety of less-visited cruising destinations – The Gambia in December 2021, the Beagle Channel in March 2022, Antarctica in June 2022, the Beagle and Patagonian Channels in December 2022 and, most recently, the west coast of Chile. Fulfilling the criteria so perfectly, it is little wonder that they received multiple nominations for the 2022 Vasey Vase.

Both Swedish nationals, Lars and Susanne met in 2015 on Sweden’s west coast. Lars had sailed since childhood and had owned Sea Wind , a 1979-built Fantasi 37, for twelve years. Susanne had never been on a sailing boat before. Nevertheless, in less than an hour they decided to get married and sail around the world. Within three months Susanne had moved from Stockholm to live aboard Sea Wind in Gothenburg, where she took a variety of navigation and radio courses. Lars gave up his job managing an engineering company and Susanne hers as head of security in a maximumsecurity prison, and in April 2017 they set off on a journey which, over the past six years, has covered more than 40,000 miles and ranged from 68°N to 65°S.

One of their nominators describes how ‘Lars and Susanne have spent almost a year cruising amongst snow, ice and glaciers, exploring the wildest terrain in Chile. As opposed to many sailors, who round the Cape and continue on through the Beagle

Susanne and Lars Hellman on Sea Wind’s bow

Susanne and Lars Hellman on Sea Wind’s bow

Channel and into the Pacific, their trip included a side visit to Antarctica and prolonged periods in various Chilean ports along the way, giving insight into life in these remote areas. They take magnificent photographs and share their

experience of weather and navigation for those who follow. It’s been a delight to follow them on their adventures.’ Another mentioned how ‘During their time in Antarctica they both caught Covid and were seriously ill, while also having to manage their boat in a severe storm. In the present Southern summer they have continued their travels northwards through the Chilean Channels, continuing to document their trip with superb photos and descriptive text on Facebook and in the Newsletter’. Their travels can also be followed on their blog at http://syseawind.blogspot.com/.

They were unable to attend the Annual Dinner to accept their award, but we were delighted to welcome Kajsa Hellman to accept it on their behalf.

The Club’s oldest award, dating back to 1960, the OCC Award recognises valuable service to the OCC or to the ocean cruising community as a whole. It was decided in 2018 that the OCC Award should be split into two categories, one going to a member, normally for service to the OCC; the other, open to both members and non-members, for service to the ocean cruising community as a whole.

Two OCC Awards for 2022 were made to members, both of whom richly deserve the Club’s thanks and recognition – Daria Blackwell, for more than a decade of service to the OCC in posts ranging from PR to Vice Commodore leading the Club’s 2020 pandemic response in the Atlantic, and Jeremy Firth for his sterling work as editor of the Newsletter for the past six years, only retiring at the age of 80.

Daria Blackwell has held numerous positions in the OCC since she joined in 2011 following three Atlantic crossings with her husband Alex and cat Onyx aboard Aleria, their Bowman 57. Their dream of circumnavigating was cut short by illness in the family and instead she was co-opted on to the OCC Strategy Team by then-Commodore

John Franklin. She joined the General Committee soon after and has been deeply involved in OCC activities ever since. As her nominator remarked, ‘The number of hours she puts in daily are pretty much equivalent to a full time job’.

Daria’s background in marketing communications made her a natural to take the Club’s PR in hand, and she also compiled a marketing plan to increase awareness of the benefits of joining the Club among bluewater cruisers. This was implemented over several years and led to a noticeable increase in new memberships. For several years she co-chaired the Awards Committee, encouraging nominations, liaising with the panel of Awards judges, publicising the results to the global press and assisting with organisation of the Annual Dinner and Award presentations.

In 2013 Daria and Alex became Port Officers for Westport, Co Mayo, their home area on Ireland’s beautiful west coast, exploring it thoroughly and writing a cruising guide, Cruising the Wild Atlantic Way. In 2017 she was elected a Rear Commodore and took on the role of web editor on top of her other responsibilities. This involved collecting articles and photos from members, editing and uploading them, writing original articles on subjects of interest to members, reporting on events and intercepting items on social media. To increase the visibility of the OCC and highlight members’ adventures, Daria worked with global media outlets such as Noonsite and Sail-World to share OCC news. She took on responsibility for proof-reading and supervising the production of the monthly e-Bulletin as well as for overseeing Facebook and initiating the OCC’s presence on Twitter, Instagram, Linked-In, YouTube and ISSUU – all in addition to her previous tasks. When a Vice Commodore position fell vacant in 2019 she was elected, serving a full three-year term plus an extra year. During that time she led the OCC’s pandemic response in the Atlantic, for which the Club was awarded the Royal Cruising Club’s Medal for Services to Cruising for 2020.

Accepting her OCC Award at the Annual Dinner, Daria told us:

‘I am truly honoured to be receiving this award. I talked about some of the benefits of volunteering at the pre-AGM talk yesterday, but by far the greatest benefit of this journey has been getting to know many of the people who make up the OCC. Yes, they are extraordinary sailors, but they are moreover extraordinary people from all walks of life, some of whom have become lifelong friends. The cruising lifestyle is a great leveller of egos so you rarely start a conversation with a distance sailor by asking what he or she does for a living. Instead you talk about all the extraordinary things you’ve seen and experienced out there, the challenges you’ve overcome and the fascinating people you’ve met along the way.

So I dedicate this award to all the extraordinary people who have touched my life since this journey began. May our paths cross often. I also want to thank the OCC for setting up Platinum Anniversary events throughout 2024 so I can celebrate my 70th birthday all year long!’

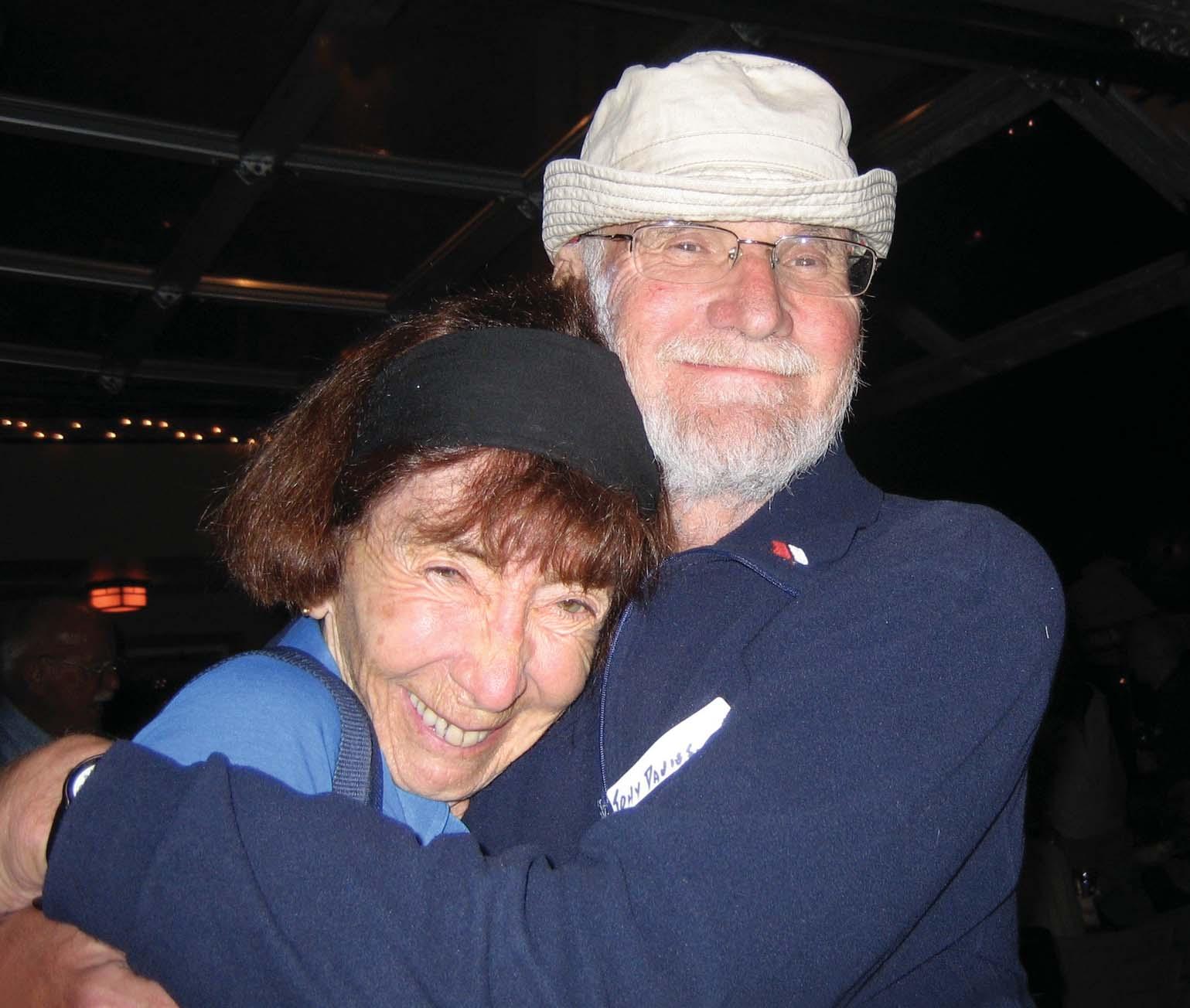

Jeremy Firth has been messing about in boats for all his long life, and still is. He was introduced to cruising as a teenager in a 60ft (18m) jackyard topsail ketch and, after spending time in landlocked Canberra at university and then in the civil service, returned to his native Tasmania in 1979 to build (with considerable expert help) Rosinante, a steel, round-bilged Adams 40 with a centreboard, which he still owns. From 1998 to 2001 he sailed Rosinante round the world, taking in the Great Capes of the Southern Ocean, the French canals and north as far as the Baltic Sea and the Scottish isles. His book about the voyage, Round the World with Rosinante was reviewed in Flying Fish 2016/2. For much of it he was joined by Penny and they have been together ever since. In the years since their return to Tasmania they’ve circumnavigated the South Island of

New Zealand, made many cruises along Australia’s east coast and acted as Radio Relay Vessel for nine out of the last ten 800-mile Van Diemen’s Land Circumnavigation

Cruises organised by the Royal Yacht Club of Tasmania. Jeremy also edits the Tasmanian Anchorage Guide , essential for those cruising in the island’s waters.

Jeremy didn’t discover the OCC until 2007. When he did he joined without delay but remained one of the Club’s ‘silent majority’ until 2016 when the call went out to find a replacement for Colin Jarman as Newsletter editor. There were a number of applicants, but few had all the skills required. In the end it came down to just two and the Board were unanimous in their final choice. Jeremy was 74 when he became Newsletter editor and it was initially viewed as a relatively short-term assignment on both sides. Under Colin’s training and supervision, however, Jeremy fitted into the role so perfectly that the Club never looked back. Neither, fortunately, did he.

Jeremy remained unfailingly professional throughout his six years as editor, meeting every printers’ deadline even when supporting family members through serious illness. An unexpected bonus were the chartlets that he frequently produced to illustrate members’ cruises, a skill honed as editor of the Tasmanian Anchorage Guide. Every editor relies on his or her proof-readers and Jeremy’s team – known as the Posse – clearly enjoyed working with him, several staying the entire six years. One wrote that, ‘I am particularly conscious of the time and effort needed to produce a quarterly publication based on voluntary contributions. Not only does it require normal editorial skills but also considerable effort to develop the enthusiasm of contributors and keep the interest of the membership. I have thoroughly enjoyed working with Jeremy ever since he began editing the Newsletter.’

Jeremy was unable to travel from Tasmania to receive his OCC Award in person –he was making the most of the austral autumn to go sailing – but asked to have what he’d written in his last Newsletter read out to those present. Of necessity it has been cut slightly here:

‘It was with something of a heavy heart that I signed off as editor of the OCC’s quarterly Newsletter. Some six years ago the call went out for

someone to replace the previous editor, Colin Jarman, who was finally succumbing to a serious illness. I put my hand up to fill in on a temporary basis until someone more appropriate could be found. I recall writing an e-mail in which I pointed out why I was not the right person to take over permanently. I was (then) 73 years old, my aged and grog-sodden brain wasn’t what it used to be and I lived on the other side of the planet. Word came back that an aged and grog-sodden brain sounded aspirational and did I want to be considered for the task? How could I refuse! This six-year temporary appointment has been very satisfying and great fun, collecting contributions from all over the world, many from places that Penny and I visited during our ocean-walloping years, as well as from regions we missed.

It remains to bear witness to those who have contributed their unwavering support to make my time as editor of your Newsletter more or less successful. The list is long and includes members past and present of the various OCC management functions, particularly Anne Hammick and Zdenka Griswold, in succession my ‘bosses’ as chairwomen of the Publications Sub-Committee, the small but effective proof-reading posse of volunteers who ride shotgun on the editorial process and pick most (but never all) the nits in each edition and, of course, the OCC membership who have contributed words and pictures about their cruising lives.’

This award, which can go to either a member or a non-member, recognises valuable service to the ocean cruising community as a whole.

Once again two OCC Awards were made, to long-time OCC member Russell Frazer and to non-members Patricia Dallas and David Sapiane, who run the annual OCC NE USA SSB Net and Gulf Harbour Radio in New Zealand respectively.

When nominating Russell Frazer, his proposer reminded the judging panel that, ‘Twenty years ago, in early 2002, Russell ran the Big Fish Net for yachts crossing the Atlantic from the Canaries to the Caribbean. It was not exclusively for OCC members, but many participated in it. More recently he has run the annual OCC NE USA SSB Net, as an occasional Net Controller prior to 2013 and annually since 2014 with the exception of the Covid year of 2020, bringing together cruisers between New York and Nova Scotia. It operates daily except Sundays at 0700 EST on 6227 kHz USB, switching later to 4036 kHz USB. Open to both members and non-members, it has been responsible for many joining the Club.’

Russell was aboard his Peterson 44 Blue Highway in the Bahamas at the time of the Annual Dinner, but wrote:

‘I learned about two-way communication when my dad bought me a CB radio back in the CB radio craze of the 1970s. I actually had a radio base

station shack (closet) and had so much fun meeting new people over the airwaves. Eventually I went on to drive 18-wheelers in the late ’80s, always using CB as a safety and entertainment device.

I always say SSB is only as good as the various nets that are available. I was a net controller in the late ’90s on the US East Coast ‘Cruiseheimers net’ (8152 at 0900 EST). When we headed east across the Atlantic out of their range I knew I needed to start a new net, so in Bermuda I put up a notice in the customs house and we had more than 18 boats participate. Cruising Scotland in summer 2000 I put together a cocktail net – it was surprising how it grew! Later, when we met SV Amadon Light in Gibraltar as they were heading west, they suggested I take over the Mediterranean cruisers’ net, during which I would read out the German HF radio teletype forecasts.

I’ve co-ordinated or worked as a net controller on countless nets and I enjoy helping to keep cruisers connected. Thank you, OCC, for this award and for recognising an important aspect of cruising life.’

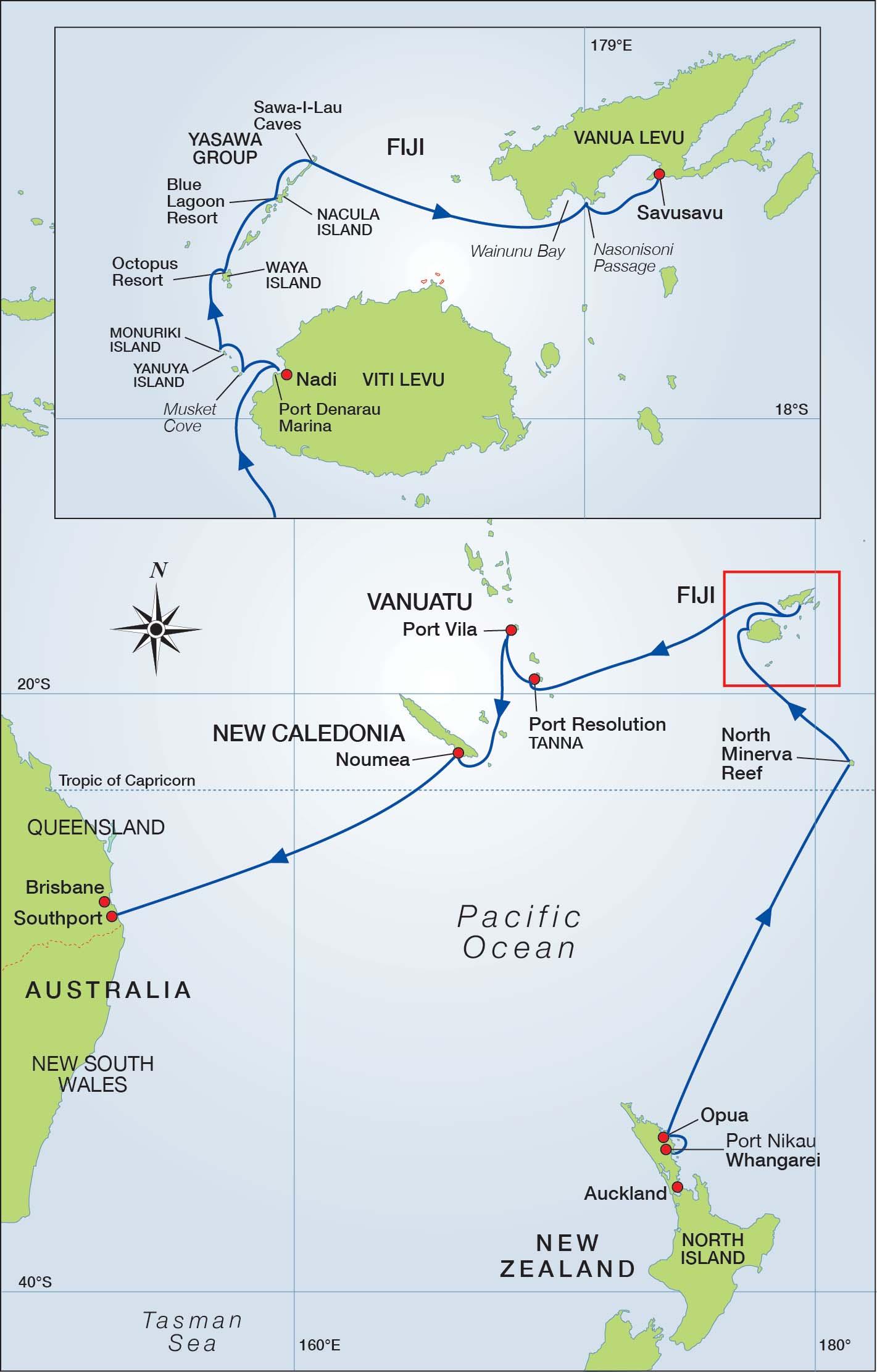

Like Russell Frazer, Patricia Dallas and David Sapiane have been on the airwaves for many years. In 2012, after 15 years of world cruising, much of it in the southwest Pacific, they established a coast radio station, Gulf Harbour Radio, ZMH286, in their home near Auckland, New Zealand. It grew rapidly, its daily SSB schedule becoming a welcome and reliable resource for cruisers on passage in the southwest Pacific. It is a totally voluntary service providing local advice, weather and forecasting, plus assistance whenever sailors in the area need support. Their nominator describes them as ‘wonderful people, incredibly generous and very supportive of OCC members and other cruisers in the South Pacific’.

Both former scientists, David’s meteorological background plus Patricia’s radio interest proved a good combination. David covers passage and island weather and often gives relevant weather-related lessons, while Patricia takes boat positions and gives her take on local and world news. They have a Marine Traffic AIS and Inmarsat station and also livestream their broadcasts on YouTube so that friends and family can tune in to listen to the vessels checking in.

In addition to their daily broadcasts during passage seasons, their website https:// www.ghradio.co.nz/gulf-harbour-radio.html offers various informative and practical papers to assist cruisers with passage planning, interpreting weather information, handling communications and, on arrival in New Zealand, getting the most from cruising the country.

They were away from home cruising New Zealand’s North Island aboard their Moody 471 Chameleon when word reached them of their win, and responded:

‘Thank you, we really appreciate this recognition of our efforts. During our 15 years of cruising we had been on the SSB radio with weather updates virtually every day, so when we decided to take a year off to see what a winter was like, friends asked us to continue broadcasting from home. All worked well until a Radio Inspector arrived one day and politely but firmly advised that we were breaking the law by using a marine frequency from land. Of course we knew that, but it is always easier to beg forgiveness than to seek permission! The inspector guided us through the application for a Coast Station licence – it was either that or lose the radio – so at that point Gulf Harbour Radio was officially

born. We never advertised our station but, like most things in the sailing world, the word spread and pretty soon we had over 500 listeners.

Gulf Harbour Radio has enabled us to return something to the cruising community – one where everyone helps each other with whatever skills they have. There is an abundance of digital weather information available, but what we provide is a seasoned explanation of reality. As David often says, ‘Weather models are computer-generated ideas based on incomplete initial data and formulas of the atmosphere that are incomplete and poorly understood’.

From feedback over the years we know our efforts have helped new cruisers understand the challenges they will face in the South Pacific and helped to make their passages safer. And of course when a passage doesn’t have the clear, sunny skies and perfect downwind conditions we all dream about, we’re told how nice it is to hear a friendly, helpful voice on the SSB each day. Thank you again for the OCC Award, we are absolutely thrilled to receive it.’

Donated by Past Commodore John Franklin and first presented in 2013, this award recognises feats of exceptional seamanship and/or bravery at sea. It is open to both members and non-members.

Many members will have followed the 2022 Golden Globe Race (GGR) which left Les Sables-d’Olonne, France on 4th September. Like its 2018 predecessor it followed the non-stop eastabout route of the original Golden Globe Race in 1968–9, won by Robin (now Sir Robin) Knox-Johnston, its only finisher. Yachts must be monohulls, less than 36ft (11m) overall and with full keels, similar to those widely available at the time of the original race. What makes this very demanding singlehanded race even more challenging is that, while competitors are tracked by Race Control using modern electronics, all onboard navigation must be by traditional methods. Of the 16 starters, three had finished at the time of writing, with two more anticipated. Nine yachts had retired, one had sunk and one had been scuttled after major damage. Visit https://goldengloberace.com/ or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_Golden_Globe_Race to read more.

The 2022 race’s only sinking occurred in the Southern Indian Ocean when, early in the morning of 18th November 2022, Tapio Lehtinen’s Gaia 36 Asteria flooded suddenly from the stern, the water reaching deck level within five minutes. The OCC Seamanship Award for 2022 went to all those involved in his textbook rescue

– MRCC* Cape Town, Captain Naveen Kumar Mehrotra and his crew aboard MV Darya Gayatri, fellow GGR competitor Kirsten Neuschäfer and Tapio Lehtinen himself. Their nominator praised the first three for ‘their exemplary co-ordination

of Tapio Lehtinen’s rescue’, and Tapio for ‘his quick thinking, prompt and effective action, good communication and positive attitude’.

Tapio Lehtinen is one of Finland’s most experienced ocean sailors and came 5th in the 2018 GGR in the same yacht. On realising the situation was irretrievable he donned his survival suit, grabbed his emergency bag and took to his liferaft, activating his EPIRB as he did so. This was picked up by MRCC Cape Town who informed GGR headquarters.

The closest ship to him was the Hong Kong-flagged bulk carrier MV Darya Gayatri some 250 miles away. On being contacted by MRCC Cape Town, Captain Naveen Kumar Mehrotra immediately altered course towards Tapio’s position. At about 1500 fellow-competitor Kirsten Neuschäfer, aboard her Cape George 36 Minnehaha and the closest to Tapio at 105 miles, made contact to say she had heard about the emergency and was also heading for Tapio. She was updated regularly by the Race Office, as was Tapio, who responded, ‘You can’t get any closer to the ocean, I love it but this is close enough’.

Fourteen hours later, at 0510 UTC and having averaged over 7 knots, Kirsten reached Tapio’s approximate position. It was light by then, with 20 knot winds from south-southeast. She had difficulty spotting him in the 2–3m swell, but soon the good news came through that Tapio was safely aboard Minnehaha. When MV Darya Gayatri arrived on the scene Tapio returned to his liferaft which Kirsten towed towards the ship, and at 0755 UTC Tapio was able to board via a rescue ladder. The liferaft was also retrieved before MV Darya Gayatri continued her passage to the Far East.

Kirsten Neuschäfer from South Africa, the only woman entrant in the 2022 Golden Globe Race, reached the finishing line at Les Sables-d’Olonne, France on 28th April 2023, taking line honours even without the 35 hours awarded to her for time lost during the rescue. She had led the fleet since Cape Horn and became the first woman to win a round-the-world race via the three great capes, but that was not the reason for her OCC Seamanship Award.

Kirsten started sailing dinghies as a child and has been a professional sailor since 2006 doing chartering, sailing training and deliveries. Before entering the Golden Globe Race her longest singlehanded passage had been the delivery from Portugal to South Africa of an elderly 32ft

(9 ∙ 8m) ferro-cement sloop which, like Minnehaha, depended on wind-vane selfsteering. In 2015 she began working for Skip Novak’s Pelagic Expeditions, taking researchers and film crews to the Falkland Islands, South Georgia, Patagonia and the Antarctic Peninsula.

Minnehaha, her Cape George 36, was built in Washington State in 1988, but Kirsten chose Prince Edward Island in eastern Canada to refit her for the race. The yacht’s name is best known from Longfellow’s poem The Song of Hiawatha in which it is said to mean ‘laughing water’.

Following the successful rescue Kirsten told Golden Globe Race Control, ‘I’m full of adrenaline now, I’ve been up helming all night and it’s quite something to be manoeuvring so close to a ship, but we’re all good. Tapio was on board, we drank a rum together and then we sent him on his merry way. No congratulations needed for the rescue, everyone would do the same for another sailor, thank you guys for co-ordinating it.’

As already mentioned, Tapio Lehtinen is a highly experienced ocean sailor and made his first circumnavigation in the 1981 Whitbread Round the World Race aboard Skopbank of Finland. His sailing CV also includes the Round Britain and Ireland Race, Two-Star, AZAB, the Bermuda Race and various races in the Baltic Sea. His second circumnavigation, this time singlehanded, was in the 2018 Golden Globe Race, in which he and Asteria finished 5th, thousands of barnacles clinging to her hull having made for slow sailing. One can only imagine Tapio’s emotions as he watched Asteria sink.

Far from being deterred, however, Tapio is already planning his next circumnavigation, this time skippering Galiana, a 1970-built Swan 55 yawl, in the Ocean Globe Race 2023 which leaves Southampton, UK in September. The OGR 2023 marks the 50th anniversary of the first Whitbread Race, sailed in 1973 and, like the GGR, it is sailed in yachts of the period using traditional navigation. Tapio has long been an advocate for youth sailing and will have one of the youngest crews in the race.

We were delighted that Tapio was able to attend the Annual Dinner to receive his OCC Seamanship Award. As someone who is passionate about the world’s oceans, he told us how concerned he was to witness the decrease in ocean biodiversity, the diminishing numbers of birds, whales and other sea mammals and ‘all the trash in

the sea and the smog above the shipping routes’. He plans to use the publicity around his next race to increase the awareness of different solutions to environmental challenges and to ‘work in cooperation with companies and organisations that are part of the solution, not part of the problem’. On a lighter note, and picking up on an earlier remark about how the OCC Awards were beginning to resemble the Oscars, Tapio said that of course he wanted to thank his mother but, even more, he wanted to thank Kirsten’s!

The rescue was co-ordinated by MRCC Cape Town, established in 2004 under the South African Maritime Safety Authority and currently headed by Jared Blows. It is responsible for a search and rescue region of more than 8 million square miles, one of the largest on the planet. The Centre’s motto is ‘Joining hands so others may live’ and it prides itself on its professional approach to helping those in peril on some of the world’s most unpredictable and inhospitable oceans. MRCC Cape Town was represented at the Annual Dinner by Vusi September, the Alternate Permanent Representative of South Africa to the International Maritime Organisation.

Sadly the OCC has been unable to make contact with Captain Naveen Kumar Mehrotra and the crew of MV Darya Gayatri.

Vusi September, representing MRCC Cape Town, with the Seamanship Trophy and Past Commodore John Franklin

Tapio Lehtinen speaks at the Annual Dinner, with Past Commodore John Franklin beyond

Tapio Lehtinen speaks at the Annual Dinner, with Past Commodore John Franklin beyond

First presented in 2018 and open to both members and non-members, the OCC Lifetime Award recognises a lifetime of noteworthy ocean voyaging or significant achievements in the ocean cruising world.

Two Lifetime Awards were made for 2022, to Joanna ‘Asia’ Pajkowska from Poland and to OCC Founder Member Ian Nicolson, both of whom attended the Annual Dinner to receive their awards.

Having completed three circumnavigations and some 250,000 miles at sea, Captain Joanna ‘Asia’ Pajkowska is probably Poland’s most accomplished sailor. In January 2009 she completed a singlehanded westabout circumnavigation from Panama to Panama aboard the 28ft (8∙5m) Mantra ASIA, stopping just once, at Port Elizabeth, South Africa, a voyage of some 25,000 miles which took 198 days. In 2010 Asia began her second circumnavigation, again aboard Mantra ASIA but this time with her husband Captain Aleksander Nebelski. Over 16 months they sailed some 22,000 miles, visiting 22 countries and stopping in more than a hundred places. For her third circumnavigation, in 2019 at the age of 60, she borrowed the aluminium 40 footer FanFan, sailing eastabout non-stop from/to Plymouth, UK.

Preparing Rote

66 for the 2017

Two-Star. Photo

Uwe Röttgering

Early in her long sailing career Asia competed in the 1986 Two-Star in the catamaran Alamatur III , and when living in England between 1995 and 2002 was a volunteer crew member aboard the RNLI’s Salcombe Lifeboat. In 1995, 1997 and 1999 she competed in the Fastnet Race, in 2000 in OSTAR aboard the 40ft (12m) Ntombifuti finishing 4th in her class, and in 2001 in the Transat Jacques Vabre aboard the 50ft (15m) Olympian Challenger. She also took part in many fully-crewed transatlantic races, including in 2001 with a female-only crew on the 60ft (18m) Alphagraphics in the EDS Atlantic Challenge. In the 2002/3 southern summer Asia sailed round Cape Horn to the South Shetland

archipelago aboard Zjawa IV, a 62ft (19m) wooden ketch. Between October 2006 and February 2007 she raced halfway round the world with another woman, again aboard Mantra ASIA. In 2013 she competed in her second OSTAR, this time in Cabrio 2, a 40ft (12∙2m) catamaran, the first lady to finish, and made a further four Atlantic crossings that year, all in Cabrio 2. In 2017 she again took part in Two-Star, this time aboard the Class 40 monohull Rote 66 together with German sailor Uwe Röttgering, winning the race.

For the past few years Captain Asia Pajkowska has sailed mainly in the Baltic and North Seas, often as mate aboard the Polish sail training ship STS Pogoria, engaged in an Education Under Sail programme for young people.

On stepping forward to receive her OCC Lifetime Award, Asia told us that she felt she had unfinished business after bad weather forced her to make an unplanned stop at Port Elizabeth, South Africa during her 2009 solo circumnavigation, hence her desire to attempt it again ten years later. She also joked that she hoped a ‘Lifetime Award’ didn’t mean that she was expected to stop sailing, something she certainly wasn’t planning to do!

Visit her website at https://www.asiapajkowska.pl/ (in Polish, but readily translatable).

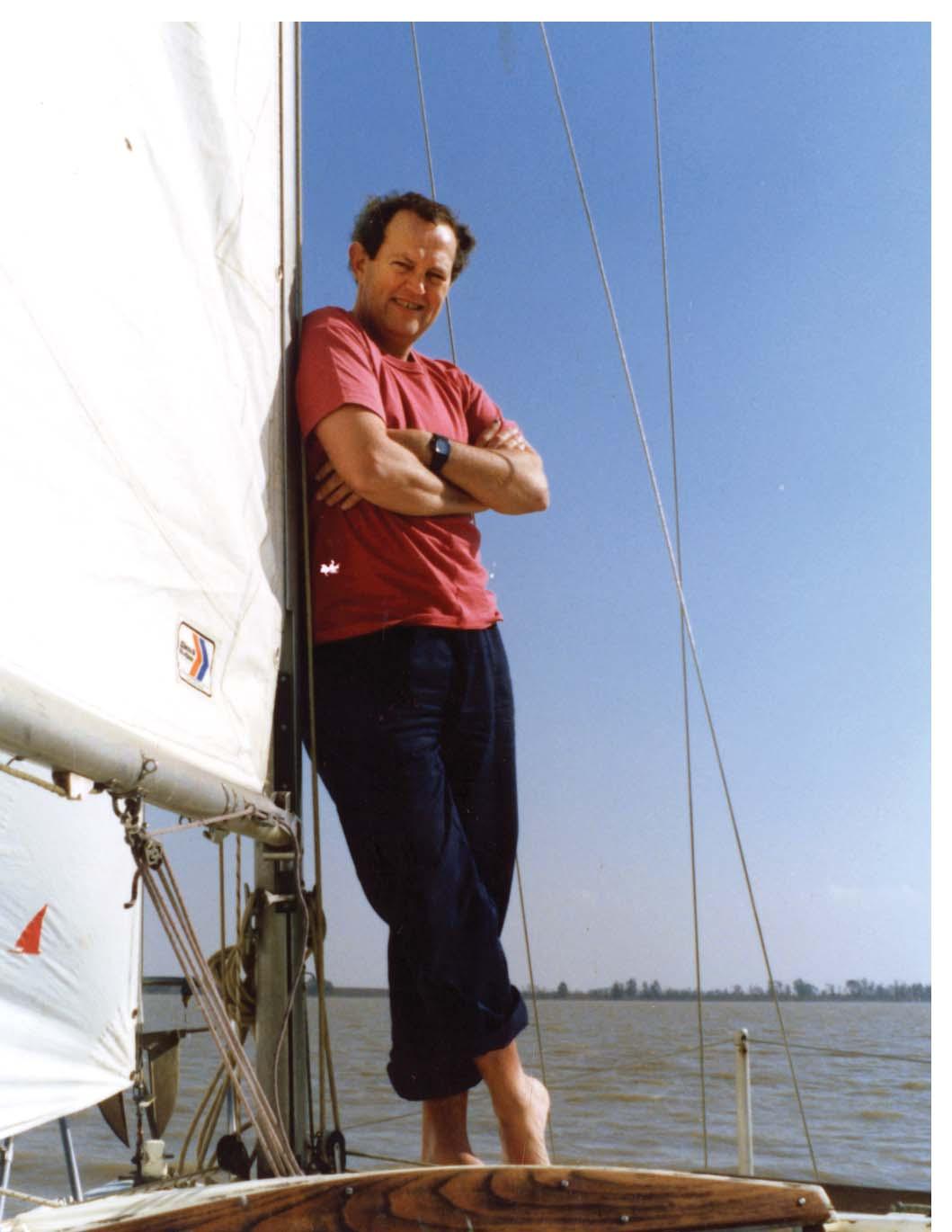

Founder Member Ian Nicolson, born in August 1928, is probably the only remaining OCC member to have watched the iconic J Class racing in the Solent prior to the Second World War – and that is the least of his claims to fame. Ian has long been a highly-respected yacht designer and is the UK’s most experienced yacht surveyor. At least 20 of his 27 published books are still in print, with two more in the works, all of

interest to and comprehensible by ordinary cruising sailors. Most have been reviewed in Flying Fish, for which Ian has also written some often very amusing articles. He has successfully campaigned yachts for more than 60 years, including winning the Scottish Tobermory Race overall, the Scottish Series overall, Cork Week and the Sigma 33 Nationals (after which he jokingly asked if he’d still be welcome in the Ocean Cruising Club!). He has been our Port Officer for the Clyde ever since the network was created in September 1959, but still finds time for regular racing in his Maxi 1000 St Bridget – the latest in a long line of yachts named after saints – interspersed with singlehanded and family cruises on the west coast of Scotland.

Ian began his design apprenticeship with Frederick Parker in Poole, Dorset in 1945 at a wage of £1/5/- (£1 25p) per week and was one of the team involved in the post-war rebuild of the 134ft (40∙8m) Fife schooner Altair. He served his journeymanship with ship and yacht builder John I Thornycroft Ltd (later Vosper Thornycroft plc). Judging from his article Cruising Sixty Years Ago, published in Flying Fish 2014/1, Ian and his sister spent their free time sailing any boat they could get their hands on, some more seaworthy than others and always on a shoestring.

Ian Nicolson speaking after the Annual Dinner, his hand on an OCC table burgee

In 1951 Ian and two crewmates emigrated under sail to Vancouver via the Panama Canal in the 45ft (13 ∙ 7m) Colin Archer ketch Maken . Once there he worked under Thorton Grenfell, Canada’s greatest yacht designer. See The Ian Nicolson Trilogy for the full story, including his purchase of the part-completed 30ft (9m) St Elizabeth and his singlehanded passage home across the Atlantic. In 1954 Humphrey Barton’s advertisement announcing the formation of a club for ocean sailors was published in The Times and Ian became a Founder Member of the OCC.

After a spell as a naval architect and race reporter on Yachts & Yachting magazine (for which he subsequently wrote a Designer’s Diary column for more than 31 years), in 1959 Ian joined the famous Glasgow design office of Alfred Mylne & Co, founded in 1896 and the country’s oldest yacht design firm. He became senior partner, and took over the firm following Alfred Mylne II’s death in 1979. Although based in Scotland, Ian travelled throughout the UK and abroad to survey yachts.

One of these was the 127ft J Class yacht Shamrock V, as Ian is understood to be the last person in the UK licensed to survey yachts of composite construction (Shamrock V features mahogany planking over steel frames).

In 2007, and about to turn 80, Ian sold the company to naval architects and design consultancy Ace Marine Ltd of Dunfermline, Scotland but, rather than take ‘early’ retirement, promptly went freelance. Drawing on a lifetime of experience, Ian Nicolson & Partners offer a wide variety of design, survey, drawing, alterations and consultancy work, specialising in historic and traditional vessels of up to 150ft (45m) LOA.

As well as sharing his vast store of knowledge via his books, Ian has given regular lectures on yacht design and surveying at three Scottish universities and found the time to build six yachts and numerous dinghies for his family, all to his own designs of course. He is a Fellow of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects, an Honorary Member of the International Institute of Marine Surveyors and was awarded a Winston Churchill Scholarship amongst other professional accolades. Most recently, at the 2023 OCC AGM, he was elected an Honorary Member, one of the highest accolades our Club can bestow.

On collecting his Lifetime Award Ian, a memorable raconteur, remarked how there was never enough time to do everything he wanted to. He told us how he and a friend had won the RYA ‘Build a Racing Dinghy for £200’ competition and how, during another competition, he and a friend completed a seaworthy dinghy from scratch in 57 minutes and 39 seconds – a world record at the time. He then apologised for missing the following day’s Sunday lunch as he had a survey to complete back in Scotland!

The Club’s premier award, named after OCC Founder Humphrey Barton and donated by his adult children, twins Peter Barton and Pat Pocock, the Barton Cup was first presented in 1981. It recognises an exceptional or challenging voyage or series of voyages made by an OCC member or members.

The 2022 OCC Barton Cup was awarded to Jon and Megan Schwartz and their sons Ronan (15) and Daxton (13), an American family who, with their two cats Poseidon and Athena, have been cruising full-time aboard their Boreal 47 Zephyros since September 2017. In this time they have sailed some 35,000 miles exploring Europe, the Caribbean, South America and Antarctica.

After crossing the Atlantic in December 2018, in April 2019 the family transited the Panama Canal before continuing to the Galapagos, Ecuador, Easter Island and Chile. They explored Patagonia for over a year, during which the two boys grew up quickly, becoming capable sailors and crew as well as racing dinghies with the local Chilean kids.

At the end of 2020 Zephyros headed south across the Drake Channel for the first of their two visits to Antarctica. They had a fascinating time exploring before returning for another year in Chile (all done legally, with full permits and no bending of Covid restrictions). Late in 2021 they returned to Antarctica, then sailed back up to Cape Horn and on into the South Atlantic, with long passages to the Falklands, St Helena and Ascension Islands, before heading back to the Caribbean to complete their multi-year circumnavigation of South America.

Zephyros during her first visit to Antarctica in 2021

Zephyros during her first visit to Antarctica in 2021

Jon, Ronan, Daxton and Megan aboard Zephyros in January 2022, before leaving Puerto Williams, Chile for their second trip to Antarctica

Driven by a desire to explore the world and experience its disappearing wilds, they have often chosen to visit places less travelled. Currently meandering through the Caribbean, they are planning for an eventual push to the northern high latitudes. Follow their travels on their blog Sailing Zephyros at https://www.svzephyros.com/.

As the Schwartz family were unable to fly from the Caribbean to attend the Annual Dinner they asked Ernie Godshalk, Port Officer for Boston, Massachusetts, to read out the words they had prepared:

‘Thank you for allowing us to share a few remarks through the voice of Ernie Godshalk on behalf of the Zephyros crew.

Our dream was to set sail to see the world and learn something together. We never considered being recognized for our adventures. The opportunity to experience so much of the world and travel in the footsteps of explorers and pioneers was the only award we sought, so it was a great surprise to learn we had been unknowingly nominated and recognized with the Barton Cup as a sailing family.

Ronan and Daxton thought it was common and routine for an 11 and a 9 year old to have sailed across the Atlantic after we first did it in December 2018 – after all, so had most of their new friends. Now 15 and 13, they think of exploring Antarctica by yacht as completely normal. Also normal to them are extended bluewater passages and night watches. Watching them grow, explore and stretch their horizons has

been most rewarding. Our challenge as parents is to keep them humble and to teach them to deeply appreciate the special moments we have been lucky enough to experience.

Cruising life has delivered the highest highs and the lowest lows. Nobody accomplishes or gets through these things alone. Along the way we have benefited from the help, counsel and encouragement of so many friends and fellow sailors including a generous handful of sailing legends. We’ve tried to repay the karma and ensure our wake remains clean. As magnificent as cruising has been, the extended separation from loved ones has been difficult and we thank our families and friends back home for their continued understanding and support.

As we have moved forward in our adventures perhaps we haven’t spent enough time reflecting on how we have grown, what we have accomplished, what we have learned from the many challenges along the way and what it all might mean. To us, being awarded the Barton Cup is a reminder to pause and reflect on just those things and to continue to remember to do so. We encourage all OCC members to do the same in their own lives and with their own journeys, whatever paths they find themselves on.’

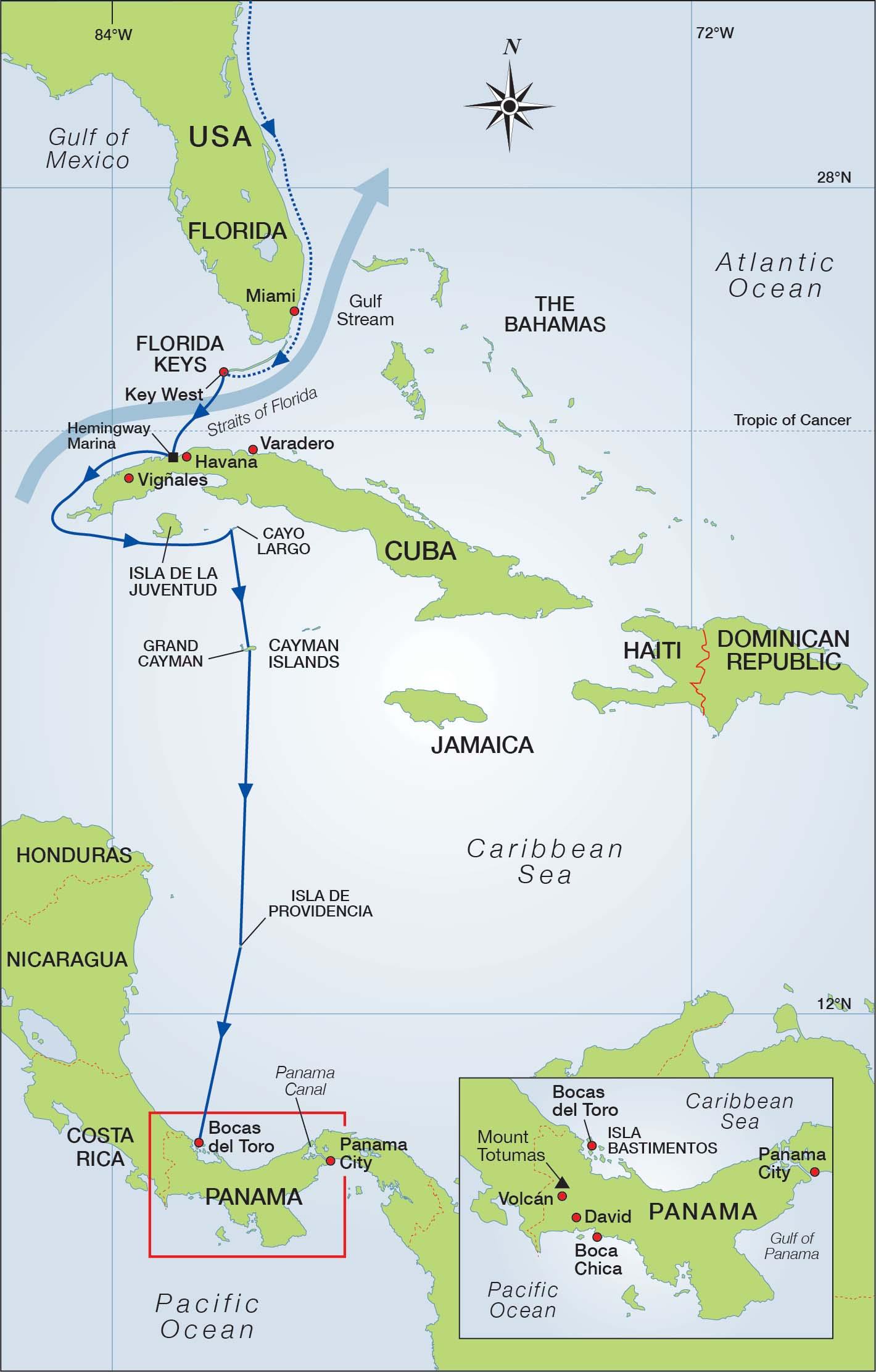

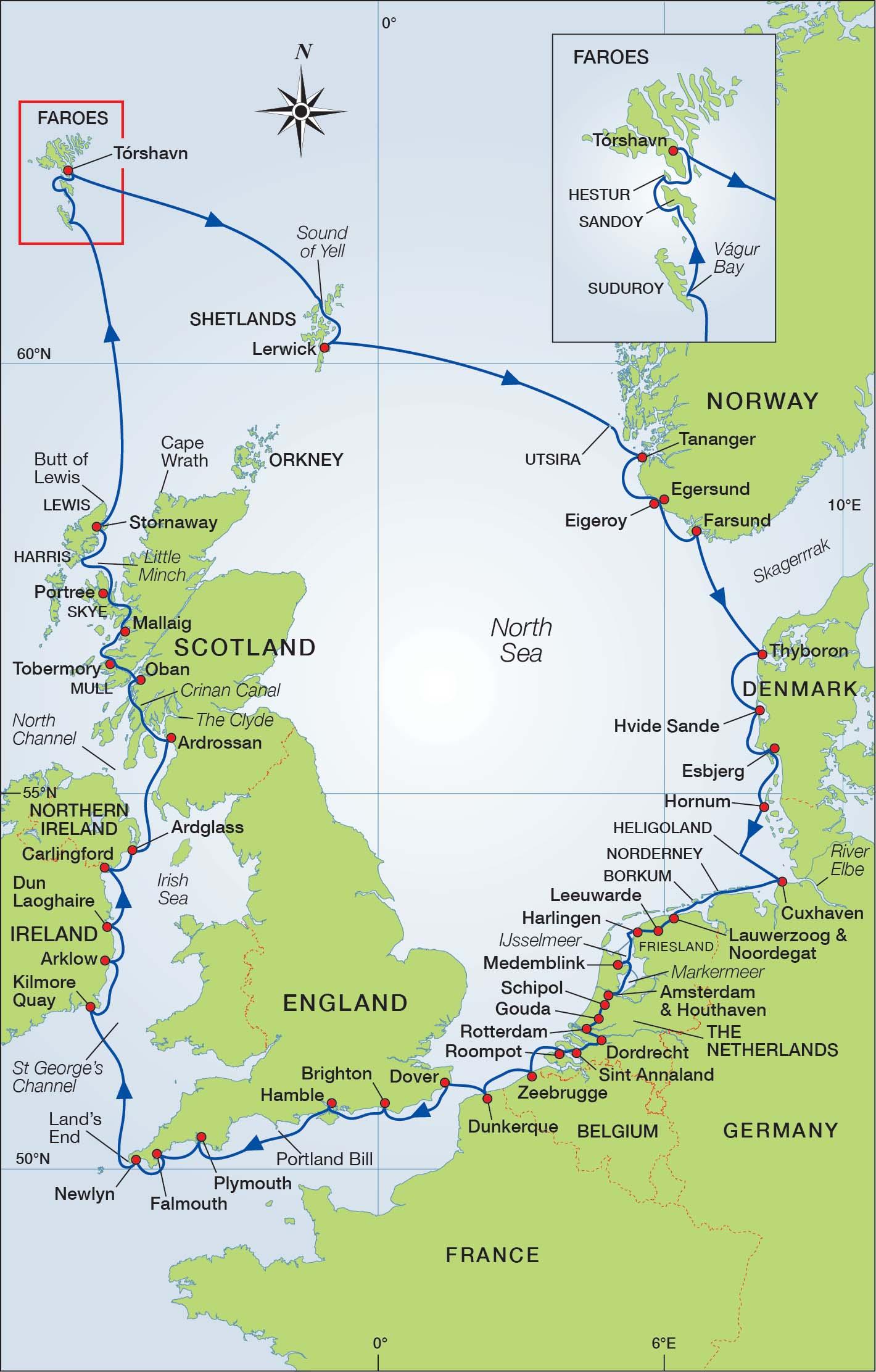

(Simon and Sally left Scotland in 2015 aboard Shimshal II, their 48ft (14∙6m) cutter, exploring Iceland and Greenland before crossing the Davis Strait to Labrador, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, where Shimshal was laid up during the pandemic. In September 2021 they were able to relaunch, and in 2022 headed south via Chesapeake Bay and the Florida Keys, where we join them now. Follow their travels at https://voyagesofshimshal.blogspot.pt/p/blog-page.html.)

Shimshal finally ready to sail south from Nova Scotia, having spent three winters in Mahone Bay during Covid

The Straits of Florida are only 90 miles wide but their crossing is a journey back in time and a voyage between two radically different cultures. We raised our anchor in Key West on the last evening of 2022 and picked our way through squadrons of jet skis, party boats throbbing with music and New Year’s Eve revellers. We were heading towards the setting sun with superyachts and schooners silhouetted against the embers in the western sky. Soon we found the breeze, allowing Shimshal to fall into her groove and surge, close-hauled, bound for Cuba.

New Year’s Eve revellers off Key West

For much of 2022 our cruise had been in the shoal waters of the USA and our deep keel an encumbrance, banishing us from many quiet anchorages and the entire length of the Intracoastal Waterway. But now, as we left the partying tumult behind and the continental shelf gave way to deeper oceanic waters, our 7ft 6in (2∙3m) keel came into its own. With apparent winds between 12 and 17 knots we sped into the night. The Gulf Stream did its best to keep us in America but the sailing conditions were perfect and the east-flowing current did little to dent our speed as we pushed southwest under clear skies and a bright half moon.

For more than 20 years we had been in waters too cold for flying fish but now, as the New Year dawned and with the strongest of the Gulf Stream in our wake, we were seeing them once more. By mid-morning the breeze had died and our trusty Yanmar engine brought us to the entrance to Marina Hemingway, about 10 miles west of Havana. As directed by the Waterway Guide*, Sally began calling on VHF from 12 miles out but it wasn’t until the fairway buoy that a polite voice answered her in good English, “Madam, you are very welcome to Cuba and a Happy New Year. Please take care in the channel as some of the buoys have been moved by Hurricane Ian”. The buoys had indeed been slightly shuffled, but the channel was easy to find and we were soon on the customs dock with a throng of uniformed officials lining up to welcome the first cruising boat of the year.

First on board was the doctor to undertake a sanitary and health check which we passed with flying colours. It wasn’t a stringent examination and was done with good humour and without the need to go below or make any kind of inspection. With those papers filled in it was the turn of the border guards, who were keen to record the number of GPSs and bicycles on board. Next the agricultural inspector, who counted our oranges and didn’t see the irony in my dyslexic declaration that we had 5kg of flowers on board. Sally politely and patiently pointed out that I meant flour!

The queue to board dwindled and finally the dock master, a former history professor, came aboard. He spent much of his time apologising for the five identical forms he had to complete, always fearful of making a mistake which would make him lose pay. His forms required 18 of my signatures – the pile of signatures on apparently pointless forms reminded me of the hundreds of thousands of prescriptions I had signed in my professional career, each of which was just as pointless in a paperless age!

As the last official left, Commodore Escrich of the Hemingway International Yacht Club of Cuba arrived with his husky, accompanied by a cluster of dignitaries. We were now allowed ashore to be formally greeted by the Commodore in Spanish via a translator, with a photographer on hand to make sure that everything was proudly documented. We have met many OCC Port Officers and Port Officer Representatives on our voyages, but Commodore Escrich’s sense of ceremony, formality and his sheer presence make him quite unique. We were invited to a formal welcoming reception at the Hemingway International Yacht Club on 4th January.

This involved more speeches, welcomes and presentations, but it was Sally who melted the hearts of the assembled crowd by making her first, and probably her last, public speech in DuoLingo Spanish. Over the previous thousand miles she had spent many of her watches talking to her phone, which hosts a rather brilliant app whose

* Waterway Guide, 2nd edition, Addison Chan, Nigel Calder and others.

artificial intelligence seems to understand her faltering phrases. So too the great and the good of the HIYC, who applauded her brave attempt to mangle their mother tongue!

With the ice broken, conversation flowed and we heard first-hand the life stories that form the backdrop to the north-bound Cuban exodus that had been so evident during our journey through the southern US states – we had seen abandoned Cuban fishing boats all along the Florida Keys. Munching canapés and sipping rum and Coke at the HIYC, a mother told us of her 20-year-old son’s journey to Miami in search of a better life. Food rationing, poverty of opportunity and the State’s firm grip drive the young and the talented to seek their fortunes on the other side of the Florida Strait.

Our month in Cuba was fascinating. A guide took us to Havana, where Castro’s statue in the Plaza de la Revolución gazed incongruously down on lines of pink Cadillacs. Near the Old Port we found the Soviet missiles that sparked the Cuban Missile Crisis 60 years ago. They are disarmed, but still point defiantly at America and are emblematic of the broken relationship between poor Cuba and its giant, prosperous neighbour.

After Havana we abandoned guides and took a trip to Vigñales in search of cooler mountain air and some cycling amongst the limestone cliffs and caves, where we enjoyed darting hummingbirds and circling vultures. It was a perfect antidote to the ocean. The taxi colectivo ride back to Marina Hemingway was in a gem of a car. With three bench seats our gleaming, green, 1952 Chevy could have seated nine but, for our journey, there were just six on board. Our ‘pilot’ for the trip was as flamboyant as his car with a huge gold watch and pendant. Singing, gesticulating and chain-smoking he kept us well entertained whilst occasionally looking at the road ahead. His ancient wheels flew over the potholes with barely a jolt and the big Mercedes diesel engine took us to speeds that the Chevrolet designers would never have intended. A memorable journey!

Our voyage southbound from Nova Scotia had been wonderfully sociable. We often cruised with buddy boats, met great folk along the way and spent our nights in crowded anchorages. As we pressed south most of our posse crossed the Gulf Stream to spend the winter in the Bahamas where, apparently, anchorages can often be crowded. Not Mangrove forest fringes much of the coast in western Cuba

Vigñales from our anchorage near Cayo Levisa

Vigñales from our anchorage near Cayo Levisa

so in Cuba, where there were very few cruisers following the restrictions placed on US crews in 2017. While we were in Marina Hemingway in January 2023 there was less than a handful of boats. During our anti-clockwise cruise from Havana to Cayo Largo on the south coast we saw no other cruisers. This rugged, remote coast some 360 miles long is fringed with mangroves and coral sand beaches, its crystal-clear water guarded by intricate reefs and islands. It is a perfect and beautiful cruising ground. The few folk we saw were fishermen who spent their days free-diving for lobsters and who happily traded their catch for cash or commodities.

We slipped into the nearly empty marina at Cayo Largo and, once again, were greeted by officials and dignitaries on the pontoon who live-streamed our docking on Facebook. Thank goodness our arrival was not as catastrophic as it had been a few months earlier in Norfolk, VA when a lapse of concentration put us aground in front

Cayo Largo Marina

Cayo Largo Marina

Shimshal reefed down for the night on passage between Cuba and Grand Cayman. Photo Jonas, SY Jollity

of the dock belonging to the newly appointed Regional Rear Commodores for South East USA! Pire, the urbane Cayo Largo dock master, gave us a very warm welcome. He had been Fidel Castro’s translator in an earlier life and has been helping cruisers on Cuba’s south coast for decades. He readily accepted my invitation to become an OCC Port Officer Representative and his new OCC PO flag hangs above his desk next to a picture of Pire and his former employer – Fidel Castro. Welcome to the OCC, Professor Pire El Cid!

The humour and spirit of Cubans was a most notable feature of our stay on this huge and fascinating island. Every day they cope with food shortages, rationing, a nepotistic and controlling State, ostracism from much of the developed world and a monolithic bureaucracy. They rejoice in their great education system and their health system and yet smile at the irony of having many excellent, homegrown doctors and nurses but empty pharmacies thanks to sanctions. They crave the return of tourism to their shores, having glimpsed the prosperity it brought when tourism briefly flourished a decade ago. Hopefully the sanctions and restrictions on travel will one day be lifted and the wonderful, proud Cubans that we met will prosper. The OCC has great connections in Cuba, with three superb Port Officers in Varadero, Marina Hemingway and Cayo Largo. OCC friends also connected us to Yoni and Addonis Perez, who work out of Shimshal moored off the cemetery at Georgetown, Grand Cayman

Marina Hemingway and can’t do enough for visiting cruisers. Their details are on our Cruising Information Map so don’t hesitate to contact them before you head for Cuba. Please take your boats to Cuba and spend your dollars there!

The brisk 140-mile trade-wind reach from Cayo Largo to the Cayman Islands went quickly. A harbour launch escorted us to the customs quay and, after checking in, took us to a free mooring where we spent a happy week or two snorkelling in the gin-clear waters, exploring Grand Cayman and being royally entertained by friends of friends ashore. Within minutes of rigging our mooring bridle the OCC crew of Blue Mist wandered over to say hello and welcome. We had low expectations of Grand Cayman, having previously only associated it with offshore banking and tax avoidance, but the warmth of our welcome, the astonishing underwater life and the supermarkets brimming with fresh produce endeared these islands to us. Another high point of our Cayman visit was the moment when I re-engineered our watermaker and wonderful, fresh water started flowing into our tanks, thus ending the 10 litres a day limit we had imposed on ourselves since leaving Marina Hemingway.