2 0 0 8

V E N D É E

G L O B E

s p e c i a l

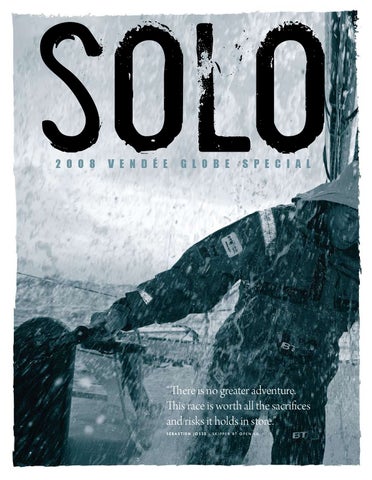

“There is no greater adventure. This race is worth all the sacrifices and risks it holds in store.” S é b a s t i e n J o ss e - S K I P P E R B T O P E N 6 0

Singlehanded aroun non stop “We’re professionals, it’s our job, but the Vendée can never be seen like another day at the office.” S é b a s t i e n J o ss e

“The Vendée Globe teaches you to go closer to the limits and that’s something that people rarely experience in modern life!” E l l e n M ac A rt h u r

“The Vendée Globe stands alone in so many areas...many other races will claim to be the toughest but this race is undeniably the toughest, most extreme, most difficult, offshore yacht race in existence - period!” Nick Moloney

“We leave, go around our small planet, and come back to where we left - only powered by the wind. I could never get tired of that, it’s magical.” Roland Jourdain

“Sometimes it’s true, we really are playing with fire” Loïck Peyron

Throughout its history, 86 sailors have entere

nd the world without assistance Start: 13h02 9th November 2008, Les Sables d’Olonne

6th edition

Established in 1989

26,600 miles, 3 capes, 3 oceans

Race record: 87 days, 10 hours, 47 min and 55 sec (Vincent Riou, 2005) Less than 100 sailors have raced solo, non-stop around the world

The 2008 lineup

7 nationalities

32 Round The World journeys completed, among which 21 Vendée Globes

1.5 million miles raced around the world between them

20 new boats built specifically for the 2008 event

ed the Vendée Globe ... only 48 have finished

©Alexander Hafemann

Record breaking, 30-strong fleet

4

co n te n ts

© T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen

contents 06 T h e V e n d é e G l o b e , a r a c e a pa rt Sailing correspondent for ‘The Independent’ examines what makes the French planetary race so special. 08 S é b a st i e n J o ss e u n v e i l e d The sailor and the man… by Jocelyn Blériot 10 A h i sto ry o f t h e V e n d é e G l o b e Dominic Bourgeois looks back on all the previous editions of the race. 16 W HAT I S BT T e a m E l l e n ? 18 M y V e n d é e G l o b e by Ellen MacArthur 20 H o w t h e V e n d é e c h a n g e d m e by Nick Moloney 24 A r o u n d t h e w o r l d Weather and strategy explained. 28 24 h o u r s o n b oa r d BT with Sébastien Josse 30 R a c e M a p 32 T h e s o l i d b o u n da r i e s o f a l i q u i d w o r l d A voyage in space and time around the globe, from legendary capes to desolate islands. 38 Z o o m ! The BT Open 60’ on full screen, by Thierry Martinez. 44 T h e V e n d é e G l o b e L i n e u p An exceptional list of entrants. 48 BT ’s a n ato m y Up close and personal with Sébastien’s monohull. 50 Da r k s i d e o f t h e G l o b e Sébastien answers our unpleasant questions. 51 Co m p r e h e n s i v e s a i l i n g C V 52 M e n at w o r k The shore team in its natural element, in pictures by Thierry Martinez. 56 O n a T i g h t R o p e How modern fibres made steel obsolete, with Yvan Joucla, rigger aboard BT. 58 T h e e x t r a c r e w m e m b e r Who steers the boat when Sébastien’s asleep? The answer from Miles Seddon, B&G. 60 A s e a o f d r e a m s How the oceans might help us shape a brighter future, by Jocelyn Blériot. 64 BT T e a m E l l e n Pa rt n e r s You can follow the latest news at www.btteamellen.com Please send us your feedback on this issue at solo@btteamellen.com

EDITED BY: Offshore Challenges Sailing Team Editor: Jocelyn Blériot Contributors: Stuart Alexander, Dominic Bourgeois, Ellen MacArthur, Nick Moloney, Julie Royer, Miles Seddon. Cover picture: Thierry Martinez / Sea&Co / BT Team Ellen Design and Production: Keith Lemmon - OC Vision All rights reserved. Published September 2008

© T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen (both photographs, this page)

On the 9th November 2008, Sébastien Josse will take on the ultimate in ocean racing on board BT; sailing single-handed, non-stop around the globe in what is widely regarded as the toughest race on earth - the Vendée Globe. Sébastien is part of BT Team Ellen and we are proud to be an integral part of the team that has made this happen. We wish him the best of luck in this unique endeavour. Working together, we aim not only to win races, but also to demonstrate how innovative approaches to communications and technology can help to create a better world. Developing a sustainable future is an important part of this partnership as businesses and consumers increasingly need to act responsibly towards the environment in which we operate. Share the journey with us. Francois Barrault, CEO, BT Global Services

6

STUART ALEXANDER

The Vendée Globe, © B. Stichelbaut/DPPI

A Race Apart t is not Jerusalem, Mecca or the Ganges, nor is it glitzy Cote d’Azur. But Les Sables d’Olonne is the top pilgrimage destination for anyone seeking the holy grail of singlehanded ocean racing. Nor would you choose to go there in what can be the hostile

whom have had a taste of the best events the international

weather of November or February. The modern-day Hulot

world of sport has to offer… Even those who have seen it

families take their holidays in the much warmer, traditional

all gladly admit the Vendée Globe is in a league of its own

months of July and August. For the rest this is a hard-

when it comes to emotional potential.

working, old-fashioned fishing town. But, every four years it attracts in only their rarified tens, the most adventurous in a sporting world that is always seeking something more extreme - and in their hundreds of thousands those who come to admire them.

The fascination is obvious, but where does it come from? Maybe there is some sort of Gallic delight in watching others suffer - they also came up with the Tour de France cycling torture - but the thought of 90 24-hour days in the tropical heat of the Equator followed by the freezing,

This is an intensely French world populated by the Brittany

boat and body battering of the gale-strewn Southern

mafia of Port la Foret and Lorient, yet this year it will be

Ocean on a track that is constantly in motion is something

more international than it has ever been, and the race’s

again. It is not what has become a two-week sprint across

power of attraction expands well beyond the boundaries

the Atlantic, and it lacks the companionship of the two-

racing simply does not do it justice.

of Western France. The Vendée Globe has made heroes, and

handed round the world Barcelona World Race. And its

The metaphor has been used and

Ellen MacArthur’s remarkable second place in the 2001

French base is entirely appropriate to its French origin. If

edition certainly propelled her from the sports pages to

you want to watch ice hockey you go to Canada or Russia,

television breakfast shows. Thirty adventurers will take the

there is something special about rugby in New Zealand and

complexity of the race’s power of

start on 9 November, and whether they are seasoned pros

something incomprehensible, to the rest of the world, about

attraction. Stuart Alexander, sailing

or debutants, will be going through a mixture of emotions

cricket in England. It may have been an Englishman, Sir

ranging from euphoria in public to terror in private. They will

Francis Chichester, who threw down a singlehanded sailing

also be carried along by the very special atmosphere which

gauntlet that was then picked up so enthusiastically by

takes a look at what makes the

is Les Sables d’Olonne when the Vendée Globe fleet gathers

the French, but the epicentre of world singlehanded sailing

Vendée Globe such a race apart.

for the pre-start jamboree.

remains France and especially, Les Sables d’Olonne.

“As a youngster”, says BT skipper Sébastien Josse, “I used

If the race were being started for the first time in the

to look at the Vendée Globe and think there was nothing

much more commercial 21st century, perhaps Les Sables

above it. Which is very natural for a kid whose dream is, one

d’Olonne would struggle to beat off opposition that could

day, to sail around the world I guess… But now that I’ve

provide more luxurious hotels, easier communication, even a

been in the professional circuit for quite a few years, that

dockside that was more suited to promenaders. But even that

perception hasn’t changed at all. Part of the race’s magic

workaday wardrobe adds to one of the essential ingredients

lies in the fact that somehow, even if you’ve managed to

that appeal to competitors, French and foreign alike, which

enter the world of those guys who used to be your heroes,

is its purity of spirit. And the Les Sables is perfect for the

the Vendée Globe still has the power to bring out the kid

openhanded welcome from the sheer number of people

within you. I think we all agree on that, there is no way one

who come to pay tribute to their heroes. They are all heroes

could become “blasé” - we’re professional, it’s our job, but

to the families, fans, and snaking lines of schoolchildren who

the Vendée can never be seen like another day at the office.”

queue patiently to walk down to the pontoon and look at

Echoing those words, British skipper Alex Thomson simply

each of the boats in the three weeks before the start. If a

states: “I just have to hear the words Les Sables d’Olonne

competitor walks through the race village or through the

and my heart starts pounding.” And the same applies to

town there are constant wishes of good will. Any excuse to

many partners, sponsors and campaign backers, most of

make contact is taken; autographs are willingly signed.

Calling it the “Everest” of offshore

abused, and no longer conveys the

correspondent for ‘The Independent’,

© JM. Liot/DPPI

A r ace A p a r t 7

“It is so simple,” says Thomson. “One man, one boat, one complete circumnavigation of the world without stopping, and without help, against all the forces of nature. It is still pure and it needs to remain pure.” It is thought that, although thousands have now conquered Everest, and over 500 have been into space, less than 100 have sailed solo non-stop round the world. They are part of a special village, a likeminded community. There is always an individual chemistry which determines relationships within that community, but their shared purpose is much stronger than nationalism in an event that has managed to become more and more professional while still being a planetary adventure. They all share the build-up of nerves and emotion in the last few days and cannot wait for the settling in period of

© J. Vapillon/DPPI

Sébastien Josse enjoying the crowd’s support prior to the start of the 2004 Vendée Globe

the first 48 hours when they return to the job they know and love. “Compared with the first time in 2000, when I was wonderfully ignorant, I now know the ropes,” says Mike Golding, returning this year for the third time. “So that probably means I am even more scared. But that is the great thing about the Vendée. You are often at the limit of both what you and the boat can take. At times like that you remember the support of ordinary people and their children.” And as Sébastien puts it, “The level of support you get from the crowd is absolutely mind-blowing and, in fact, it goes beyond what your brain can take in. It’s so strong it becomes physical, your entire person receives the warmth and best wishes sent by all the spectators packed on either bank of the canal.” If you can join them on the Vendée coast, it is an experience well worth the effort.

Fireworks for Vincent Riou’s victory in 2005

S é bastie n J osse

Sébastien Josse is about to embark on his fourth circumnavigation, this time at the helm of the BT Open 60, after having successfully tackled the three biggest challenges an offshore racer can dream of. Jules Verne Trophy, Vendée Globe and Volvo Ocean Race: no other sailor on the planet has completed all of these events and even though Sébastien is not the type of man who would walk around displaying his medals, his rivals know who they’re lining up against.

© T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen

8

all the greatest sailors are on the startline and there’s an impressive number of new boats

he man is certainly discreet and softly-spoken, a character trait some people could mistake for shyness. Yet his quiet attitude has nothing to do with a desire to avoid contact - “I take my time, it’s different”, says the skipper, “because superficial relationships are of no interest for me. I prefer to build something on the longer term, when I know who I’m dealing with, and end up with a group of friends with whom I really share something. It doesn’t matter if that group doesn’t amount to dozens of people.” That strong belief in the value of friendship is at the core of the team… PierreEmmanuel Hérissé, BT’s boat captain, is a longtime friend, and was one of the key figures in Sébastien’s 2004 Vendée Globe campaign. Undoubtedly, the skipper is known for his sense of comradeship, an image which has stuck to him during his Figaro years and aboard the Orange maxi-catamaran, for the 2002 Jules Verne effort. During that adventure he met Nick Moloney for the first time, without of course knowing they’d end up under the same BT banner a few years later! The Australian sailor comments: “He is genuine, sincere, and capable of really listening - that’s a rather rare and precious human quality in my book. Aboard Orange around the planet, we’ve lived through pretty tense and stressful moments, and his calm struck me. He’s not a guy who’s easily scared, but he doesn’t run around playing the tough guy either. I have a lot of respect for the sailor, and a real friendship for the man.” Sébastien would probably add that his fatalist state of mind explains why he can keep his cool when all hell breaks loose - no point in spending “hours ruminating about a breakage or an unfavourable weather change - that’s the way it is, you have to cope and get on with it,” he says. Of course, that could mislead you to thinking that he is an unsubtle personality, but one has to know how to read between the lines and take into account that this is a man who doesn’t like to play around with superlatives or emphatic phrases. Sure, at 33 he already has a very impressive CV and has many times been under the spotlights on the international scene, but it doesn’t seem to have affected his sense of reality. “I’m quite indifferent to the glitz of it, and if I wasn’t a professional sailor, I’d be perfectly happy running a modest shipyard”, comments Sébastien, who studied mechanics and is always keen to get involved with his technical team when the boat is in the shed. Raised under the blue skies of the Côte d’Azur in southern France, an ideal playground for outdoors activities, it did not take long for him to find his way onto adventures. “My family settled in Nice when I was very young. I’ve been a quiet child, until I discovered that there were a lot of things to see and do outside.” The sea came into the picture when Sébastien’s father, never shying away from new experiences, bought a sailboat which soon became the Josses’ secondary home. “We started to spend all our holidays and most weekends aboard, and even though I loved long cruises for the adventure they involved, I have to admit sometimes the boat itself was a bit of a chore, especially upwind. I really appreciated sailing when I hopped aboard a 420 dinghy with my elder brother… it was faster, the sensations immediately ‘spoke’ to me.” Racing only came later, and Sébastien waited until he was 18 to take part in his first regattas. Having met a local coach, he then started to train in Monaco, where an active J24 fleet was based. “Eventually, we entered some rather high-level competitions, and I became hooked. I then crewed on various boats, and after my “Bac” (A-Level), I was granted a sabbatical: my father dreamt of crossing the Atlantic with one of his sons, so we geared up for that expedition, which was our first ever real offshore adventure.”

© T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen

p o r t r ait of a ski p p e r 9

Sébastien Josse

Portrait of A Skipper S é b a s t i e n J o ss e BORN : 3 1 m a r CH 1 9 7 5 LI V E S : M e l gv e n ( F i n i s t è r e )

After a memorable journey, Sébastien and the boat stayed in the French West Indies, enjoying complete freedom. “My father flew back to France due to his professional obligations, and trusted me with the boat… so basically, I cruised around on my own for 9 months.” Needless to say this interlude dramatically sharpened the young Josse’s singlehanded skills, and shortly after his return to France he took a shot at the Espoir Crédit Agricole Challenge, a Figaro OneDesign competition for young guns. “In 1997, remembers Gilles Chiorri, OC Events Director, “I was training in Nice for my second Solitaire du Figaro, and Sébastien - whom I did not know - came to ask me if he could sail on my boat. I took him aboard for a regatta in Juan Les Pins, and immediately noticed he was talented.” Gilles‘ opinion was soon proved right, as Sébastien recalls: “That year, I won the Challenge Espoir, which gave me access to two fully funded seasons on the Figaro circuit.” The stepping stone also meant relocating to Brittany, a region with which Sébastien quickly developed a strong bond. “I landed in that universe like a kid who can’t believe his eyes - all the great names I used to read about in magazines were there, very accessible. A guy like Roland Jourdain even lent me his Figaro without asking for any deposit, and he didn’t know me at all! I learnt an awful lot during that period, attending every single course the Port La Forêt offshore racing training centre offered.” He worked relentlessly, and his rivals quickly understood it wouldn’t be long before he joined the ranks of the best in the class. Most of whom became close friends - like Yann Eliès, Jérémie Beyou or Vincent Riou. This gifted generation today finds itself among the natural favourites for this year’s Vendée Globe. In 2001, fresh from a brilliant second place overall in the Solitaire du Figaro, Sébastien became part of the Orange maxi-catamaran crew - whose project manager was a certain Gilles Chiorri - and went on to become co-holder

of the Jules Verne Trophy with a record-breaking 64-day circumnavigation. The 2004 Vendée Globe soon followed and, despite a collision with an iceberg, the skipper managed to not only finish but also capture a very creditable fifth place. His love affair with RTW competitions was about to enter a new phase as he was appointed skipper of an international crew for the 2005 Volvo Ocean Race! To this date, Josse is the only sailor to have completed all three of these events, which represent the pinnacle of professional offshore racing. Yet, he remains very humble about those achievements: “I’ve worked hard, and yes I’ve come a long way in 10 years, but there is still a lot to be done and I have a massive hurdle in front of me. The 2008 Vendée Globe is exceptional in terms of lineup, all the greatest sailors are on the startline and there’s an impressive number of new boats. The competition level has never been quite as high. This race was the first one to really capture my imagination and trigger my dreams, I’ve been putting all my energy into it and I’m really fortunate to be able to count on my partner Magali’s support, and on the dedication of my team. I know it’s very demanding for them all.” Being a pragmatic man, he is fully aware of the “selfish” aspect of singlehanded racing, and intends to make up for it in the future by getting “involved in a mode of action that could be beneficial for society. It still remains to be defined precisely, and at the moment I can only try and raise awareness concerning environmental issues in a modest way. Later on, I’ll give it more time and commit to projects that hopefully will be useful on a bigger scale… and I also intend to be a good father someday, sooner rather than later”, concludes the navigator, his eyes glistening with the memories of a childhood not so far away, a childhood whose dreams have stood the test of time. Jocelyn Blériot

VENDÉE GLOBE HISTORY

Thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, twenty-four and finally twenty: the candidates for the ultimate sailing adventure have been rather scarce throughout the Vendée Globe history, with a total of five editions so far. Those who have finished the voyage - a little more than half the fleet each time - all came ashore with a strange glint in their eyes, a subtle mix of fear and serenity. dominic bourgeois takes a look back on the 20 year history of the ultimate singlehander’s race.

1989… When it all started

Twenty years after Bernard Moitessier’s Long Way, thirteen sailors set off for another non-stop solo circumumnavigation. Another kind of challenge. Boats had come a long way since Joshua and Knox-Johnston’s Suhaili, and the skippers were no longer mere discoverers - they left with competition on their minds, with the aim of completing the fastest planetary lap ever achieved aboard a sailing vessel. In 1968, when a handful of visionaries (or madmen?) were slowly making their way around the planet, news barely made its way ashore, and the world learnt almost by accident that Moitessier had decided that coming back to the starting point was not enough. There was another life, new seeds to be sowed, and Joshua wasn’t ready to remain in the rat race - a statement that was to leave its mark on generation of sailors, including the adrenalin addicts who since then have written the most famous pages of the big Vendée book. Between Moitessier the vagabond and the 1989 Vendée pioneers, racing around the world had become an institution, fully crewed (Whitbread race) or singlehanded with stops (BOC Challenge), and it was clear for everyone that a) the planet was indeed round b) the Southern ocean could be as grey and hard as concrete. So when Titouan Lamazou, Philippe Jeantot, Guy Bernardin, Jean-Yves Terlain and a few others thought that a further step had to be taken - going out there alone and without stopping - the idea appealed to quite a few sailors, who formed an informal and eclectic fraternity. Some of them already knew the bleak atmosphere, biting cold, perpetual dampness and ferocious waves of the South. Others were complete novices - almost naive in their perception - but they all shared that burning desire to race between three capes. On November the 26, 1989, thirteen of them (a somewhat symbolic figure for superstition-prone seafarers) set sail from Les Sables d’Olonne, Vendée, for a three-month long initiation journey.

horizon beyond the

© J. Vapillon

10

BEYOND THE HORIZON 11

1989 - The pioneers All thirteen competitors are on equal terms regarding at least one aspect of the challenge. Not one knows exactly what to expect, the only non-stop singlehanded race having taken place more than 20 years before. Some of the Vendée Globe Challenge - as it is then called - entrants have experienced the Southern Ocean with a crew… but alone? A strong freezing wind catches them off-guard as soon as they exit the now famous Les Sables channel, as if to warn them straight away that the voyage won’t necessarily be pleasant at all times. A month and a half later, the wild bunch enters the Indian Ocean, at the threshold of which the world suddenly takes a whole new appearance. Fear kicks in, everything turns grey, and there certainly is no mercy for the faint hearted. Or for the gear, for that matter, and the roaring forties soon take their toll on the fleet. Bertie Reed finds himself deprived of an efficient steering system, his rudder ending up misaligned, Jean-Yves Terlain loses his mast, Philippe Poupon ends up on his side, Patrice Carpentier loses his autopilots… and Mike Plant almost runs aground in New-Zealand trying to find a sheltered bay to fix his boat. Guy Bernardin, for his part, suffers a violent toothache, and those six competitors are soon out of the race, though three of them (Carpentier, Plant, Bernardin) will nevertheless finish the adventure. For the seven men still in the competition, the situation is not exactly much better, as Pierre Follenfant has nothing but a stub of rudder left, while Alain Gautier sees one of his spreaders dangle pitifully. Philippe Jeantot fights a damaged gooseneck, and at the end of the day only Jean-François Coste seems to enjoy a relatively safe ride aboard the old Pen Duick III, a boat which already knows what vicious tricks the Southern Ocean is capable of throwing at intrepid sailors. From white hell to blue paradise After the Cape of Good Hope, it looks like Titouan Lamazou is the only one to be able to claim victory he’s in the lead some 400 miles ahead of his pursuers, and furthermore, his boat is intact. His shore team answers every interrogation, and his router makes sure all the rough spots are avoided. Yet, two sailors can still change the scenario: Loïck Peyron performs a textbook manoeuvre to rescue Philippe Poupon, and Jean-Luc Van Den Heede makes amazing progress downwind aboard his red “cigar”, a very narrow ketch. After a month spent in “white hell”, once Cape Horn has been rounded, the last Atlantic stretch turns into a dash towards the finish line. The three musketeers have to cope with the St Helena high pressure system, and find themselves very close to each other on approaching the equator. But the suspense is short-lived, as Lamazou quickly gets rid of everything he doesn’t need in order to make his boat lighter and makes the most of his shore-based router’s tips. After 109 days, 8 hours and 49 minutes at sea, he’s triumphantly back in Les Sables! Loïck Peyron follows some 30 hours later, and Van Den Heede completes the podium three days later. Two months after the winner, Jean-François Coste concludes this first edition of the singlehanded non stop race around the world. The welcome in Vendée is, for the winner as for every single finisher, so generous that it will instantly become the symbol of the event, a real social phenomenon on the local scale. A second edition seems inevitable!

1992 - The global regatta Having barely had the time to recover, some like Gautier, VDH, Poupon and Peyron are already focusing on another planetary lap, and are joined by a new generation of sailors for whom racing is as important as taking part in the adventure. Compared to 1989, there

is one more boat on the startline (fourteen), but as many at the finish (seven). The curtain just fell on the first edition of the race, yet the next one is already looming… Ashore, the inauguralVendée Globe raised a massive interest and while the singlehanders were battling it out in an hostile environment, spectators were monitoring their progress from the comfort of their armchairs. The second start is scheduled for 1992, which ensures the race doesn’t collide with other major offshore events (the BOC Challenge, namely). There clearly is a growing interest among the sailing community, and a huge leap in terms of entries is expected - yet natural selection soon takes its toll, eliminating the unreasonable, unfunded or simply imaginary campaigns. And before the race even begins, the ocean’s cruelty makes the headlines: Mike Plant is lost at sea whilst trying to reach Les Sables d’Olonne for the event, and his state-of-the-art 60-footer Coyote is found upturned and desperately empty in the middle of the Atlantic. Like in the previous edition, the Bay of Biscay proves very angry and bad news make their way back ashore right after the start. Nigel Burgess is reported missing (his body will later be found at Cape Finisterre), Thierry Arnaud and Loïck Peyron throw in the towel, the latter seeing his brand new boat delaminating before his eyes… Four entrants - VDH, Poupon, Malingri and Parlier - go back to Les Sables to carry out some repairs, their problems ranging from lost rigs to unreliable keels. The first week at sea is particularly harsh on the boats, and only Alain Gautier, Bertrand de Broc and Nandor Fa make it through the Cape Finisterre gale without any damage. In the light airs off the Portuguese coast, De Broc pulls a nice trick out of his hat and takes the lead of an already decimated fleet, since Poupon, VDH and Parlier will eventually re-start from Les Sables with a few days to catch up. Up in front, Alain Gautier benefits from the sheer speed of his Finot purposed-designed ketch: the Breton sailor has learnt the lessons from his first Vendée experienced, and commissioned a ketch-rigged downwind machine. Undisputed leadership Gautier clears the African western tip with a comfortable lead, and can look in his rearview mirror in order to control his rivals whilst concentrating on sparing his gear. Some 800 miles behind, his pursuers start to think the case is closed, but meteorological twists of fate suddenly modify the deal. Unlike the first edition, shore-based routing is now forbidden so strategic decisions have to be taken by the skipper alone. Furthermore, compulsory waypoints have been put in place by the organisers in order to reduce the risk of collision with drifting ice. As he rounds Cape Horn, Gautier knows he can’t completely rule out the possibility of seeing Poupon catching up on him, but further back, all hell breaks loose: Alan Wynne Thomas hurts his ribs and pulls out of the race in Hobart, Vittorio Malingri suffers from a broken rudder, Bertrand de Broc is diverted towards New-Zealand since his keel cannot be trusted anymore, and Bernard Gallay can’t seem to solve his electrical problems. Only seven skippers remain in the race, among which a serene but rather slow Spaniard (Jose de Ugarte), a Hungarian disappointed by his boat and a Frenchman (JeanYves Hasselin) following in Jean-François Costes’s footsteps. Alain Gautier wins the second Vendée Globe in 110 days, 2 hours and 22 minutes, and the battle for second place takes on a very surprising dimension: VDH tries hard, but without success, to stop his boat from delaminating, while Poupon sees his mast come down only three days before crossing the line!

Titouan Lamazou’s Ecureuil d’Aquitaine © J. Vapillon

An exhausted Lamazou © J. Vapillon

Alain Gautier wins the second edition © H. Thibault/DPPI

12

VENDÉE GLOBE HISTORY

Christophe Auguin’s radical Finot-designed Geodis, winner in 1997 © H. Thibault/DPPI

Patrick de Radiguès runs aground in Portugal, 2000 © J. Vapillon

Moonlight aboard Dominique Wavre’s UBP, 2000 © D. Wavre/DPPI

1996 - Southern wrath

2000 - The great leap forward

The pioneering era is definitely over and the Vendée Globe is now about sheer competition, even if that implies sailing on the edge in iceberg territory or enduring the continuous noise and slamming of carbon hitting waves. The boats are faster than ever, the singlehanders largely come from the Solitaire du Figaro training camp. But the oceans couldn’t care less - they keep Gerry Roufs and knock three boats down, resulting in very hazardous rescue operations. This time, sixteen solo sailors gather on the startline, even if technically one of them is a “pirate” and won’t enter the official rankings - Raphaël Dinelli has not completed his qualifier and thus isn’t officially entered, but he nevertheless leaves with the organisers’ permission. And once more, the Bay of Biscay strikes hard, forcing Didier Munduteguy and Nandor Fa to retire to Les Sables d’Olonne. Right after the opening storm is over, the race immediately takes its frenetic pace, and competitors push hard on their way to Good Hope and the Southern Ocean. Autissier, Parlier and Auguin are in close-combat mode, but the battle is an exhausting one, and a strange disease seems to affect rudders… which break one after another. Parlier and Autissier have to stop and repair, are out of the race, giving Auguin some room to breathe. The solid Normand doesn’t seem to ease off though, and spends half a week clocking up more than 350 miles a day. Behind him, it’s simply chaos, and the back of the fleet is hit by a fierce storm, generating winds so strong they capsize 60-footers as if they were small dinghies. The red alert mode kicks in - Tony Bullimore has lost his keel, Thierry Dubois has gone turtle and Raphaël Dinelli is clinging to his monohull turned iceberg, as 90% of the vessel is now underwater. The Australian Rescue teams manage to bring everyone back ashore safely, and Pete Goss takes Dinelli on board after having fought upwind for three days to reach him. Desperately calling Gerry After this shocking episode, one could hope that the wind gods would have regained some sense of serenity… yet their ire seems long-lasting, and a deafening silence echoing from the South Pacific starts to have everyone ashore panicking: Gerry Roufs does not answer any calls. Competitors are diverted to the zone where he should be, search operations are set up, but to no avail. His monohull will eventually end up, capsized and empty, on the Chilean coast six months later. On the racing front, the argument is settled, Christophe Auguin is already off the Brazilian coast while his pursuers are still suffering around the Horn. After 105 days, 20 hours and 31 minutes, the Normand can bid farewel l to solo ocean racing, having bagged three consecutive victories around the planet (winning the Vendée Globe after two BOC Challenges). More than a week later, Marc Thiercelin takes second place, closely followed by Hervé Laurent, and Eric Dumont. Pete Goss, the British hero, crosses the line three weeks after the winner but his feat aboard the only 50-footer of the fleet does not remain unnoticed. Finally, having been faster than pioneer Jean-François Coste but as blissfully happy to have gone beyond herself, Catherine Chabaud becomes the first woman ever to complete a solo race around the world…

If the fourth edition of the Vendée Globe did not represent a cultural revolution, on the strategic and technological fronts, the revolution was blatant. During the first three events, the reference time around the planet had remained very stable, but that state of affairs was to change dramatically… And as Michel Desjoyeaux managed a 12% gain over the previous record, in his wake Ellen MacArthur became that year’s unmissable sailing revelation. While lessons were learnt following the dramatic events that occurred in 1997, the Vendée Globe takes on a genuine international stature and welcomes British, Swiss, Italian, Belgian, Spanish and Russian skippers. The safety regulations have become drastic, righting tests are now compulsory, the qualification process is lengthy and tough - even by the elite’s standards. Even the start of the 2000 edition is postponed by five days due to a severe storm in the Bay of Biscay! Mishaps occur in the first miles of the course, Mike Golding losing his mast, going back to Les Sables to repair and re-start. Roland Jourdain, betrayed by a halyard, does just the same. Patrick de Radiguès won’t have a second chance after running aground in Portugal… and Bernard Stamm, Richard Tolkien, Eric Dumont and Javier Sanso all throw in the towel before the Indian Ocean. An ocean where life is lived at full throttle, with Dominique Wavre setting a new 24-hours solo record with 432 miles, and Yves Parlier unfortunately dismasting off the Kerguelen archipelago. A couple and a “survivor” On January 1, 2001, singlehanders enter a new era which doesn’t bring good news to leader Michel Desjoyeaux, whose engine refuses to start - without any energy, there is simply no way he can hope to maintain his first place and win the race. But after 4 days of relentless work, the Breton sailor finally manages to get his motor running again, thanks to a clever system made of ropes and blocks. Meanwhile, Roland Jourdain who has come back from the depths of the fleet is forced to make a pit stop in a bay close to Cape Horn in order to fix his mainsheet traveler. Thousands of miles further west, Yves Parlier drops anchor off Stewart Island (New Zealand) to repair his mast, having to live on wild mussels. The “extraterrestrial”, as he is soon nicknamed, will manage to re-step his fixed mast alone, but also to finish the race overtaking two rivals in the process! In the Atlantic battle, Michel Desjoyeaux is under tremendous pressure from Ellen MacArthur, gradually gaining miles along the Argentina coast, while Roland Jourdain is quickly catching up with Marc Thiercelin. Not to mention the duel between Thomas Coville and Dominique Wavre: for the first time in four editions, nothing is set in stone when only 25% of the total distance remains to be sailed. At the Equator, Michel and Ellen are only a few miles apart, but the Breton’s east position pays off while MacArthur’s Kingfisher has to face appendages and rig problems. Desjoyeaux wins in style, becoming the first singlehander to sail around the world in less than 100 days (93 precisely), MacArthur takes second place and becomes an instant icon, while a jubilant Bilou completes the podium.

As they are about to round the cape of Good Hope,

BEYOND THE HORIZON 13

2004 - The acceleration of time

PRB and Vincent Riou clearly dominated the 2004 edition

© B. Stichelbaut (All photographs, this page)

Less than 7 hours apart after 87 days at sea? The Vendée Globe definitely deserves its “planetary regatta” appellation after the 2004 edition. The pace is set in the early stages of the event, and if managing the distance remains crucial, taking the advantage at the starting gun becomes as vital. It’s also a game of control, and Vincent Riou is unable to rest before crossing the finish line, having to cope with Jean Le Cam breathing down his neck. For a handful of entrants, the Vendée Globe remains an adventure above all, yet they know they’re not in the same league as the hardcore racers, who spent years practicing every single manouvre in order to save precious seconds. And as the battle rages on at the front of the fleet, at the back it’s a matter of living a dream. For once, the Bay of Biscay welcomes the monohulls with favourable conditions, and it’s all downwind until the Equator, reached in just 10 days! Which does not go without some collateral damage - only the first six sailors manage to escape the Doldrums swiftly, while their rivals get trapped and can only watch the leading pack sail away at speed. A pack which will eventually be divided by the St Helena high pressure system, dictating the shape of things to come. Close combat, icebergs and gear failure As they are about to round the Cape of Good Hope, Vincent Riou and Jean Le Cam sail within sight of each other, after 6000 miles at sea! The two men have already left Roland Jourdain and Sébastien Josse more than 300 miles in their wake, while Mike Golding lies some 36 hours behind - but the bulk of the fleet is four days late! Things only get worse as the leaders enter the Roaring Forties, the only choice for their pursuers is to push hard to try and catch up. Risky business: Alex Thomson is the first to retire and sails towards Cape Town with a hole in the deck, and soon Roland Jourdain sees his keel threaten to part from the boat, forcing him to divert towards New Zealand. Only Mike Golding manages to make some gain on Sébastien Josse, who unfortunately hits a growler in the Pacific Ocean: the bowsprit of his Open 60 breaks, leaving Sébastien unable to hoist his big downwind sails for the rest of the race. Up in front, Le Cam and Riou trade places on their way to Cape Horn, a landmark which theoretically symbolises liberation, but the Atlantic decides otherwise and traps Le Cam in a massive high pressure calm zone. That doesn’t mean safety for Riou, since Golding is catching up quickly. The fleet is spread over a very large area when the leading trio crosses the Equator for the second time, and Karen Leibovici hasn’t yet gone through half of the Pacific! Then catastrophic keel failure for Australian Nick Moloney as the appendage simply falls off, close to the Brazilian coast, soon followed by Mike Golding’s which decides to part company 50 miles before the finish line! The final sprint is riveting, but eventually PRB claims her second win, this time helmed by Vincent Riou, Desjoyeaux’s disciple, who smashes the existing record by six days. 87 days to sail solo around the planet, which equates to 12.73 knots of average speed over 26,714 miles (15mph/24kmh) of average speed powered by wind alone!

Vincent Riou and Jean Le Cam sail within sight of each other, after 6000 miles at sea!

14

V E N D É E G L O B E histo r y

Vendée Globe final standings 1989-1990 1.

Titouan Lamazou - Ecureuil d’Aquitaine -109 d 08 h 49 mn

Retired

2.

Loïck Peyron - Lada Poch III -110 d 01 h 18 mn

Patrice Carpentier - Nouvel Observateur - Autopilot issues (Malouines)

3.

Jean-Luc Van Den Heede - 3615 MET -112 d 01 h 14 mn

Mike Plant - Duracell - required assistance (New Zealand)

4.

Philippe Jeantot - Crédit Agricole IV -113 d 23 h 47 mn

Guy Bernardin - Okay - Dental problems (Hobart)

5.

Pierre Follenfant - TBS-Charente Maritime -114 d 21 h 09 mn

Jean-Yves Terlain - UAP 1992 - Dismasted (SE of Cape Town)

6.

Alain Gautier - Generali Concorde -132 d 13 h 01 mn

Bertie Reed - Grinaker - Structural + rudder issues (Cape Town)

7.

Jean-François Coste - Cacharel -163 d 01 h 19 mn

Philippe Poupon - Fleury Michon X - Capsized (S of Cape Town)

1992-1993 1.

Alain Gautier - Bagages Superior - 110 d 02 h 22 mn

Retired

Lost

2.

Jean-Luc van D en Heede - Sofap-Helvim - 116 d 15 h 01 mn

Bernard Gallay - Vuarnet Watches - Autopilot issues

Nigel Burgess - Yachts Brokers

3.

Philippe Poupon - Fleury Michon X - 117 d 03 h 34 mn

Vittorio Malingri - Everlast-Neil Pryde - Broken rudder

Drowned (Cape Finisterre)

4.

Yves Parlier - Cacolac d’Aquitaine - 125 d 02 h 42 mn

Bertrand de Broc - Groupe LG - Keel failure (New Zealand)

5.

Nandor Fa - K&H Bank Matav - 128 d 16 h 05 mn

Alan Wynne Thomas - Cardiff Discovery - Broken ribs (Hobart)

6.

José de Ugarte - Euskadi-Europa 93 BBK - 134 d 05 h 04 mn

Loïck Peyron - Fujicolor - Delamination (Les Sables d’Olonne)

7.

Jean-Yves Hasselin - PRB/Solo Nantes - 153 d 05 h 14 mn

Thierry Arnaud - Le Monde Informatique - Lack of preparation (Les Sables d’Olonne)

1996-1997 1.

Christophe Auguin - Geodis - 105 d 20 h 31 mn

Retired

Lost

2.

Marc Thiercelin - Crédit Immobilier de France - 113 d 08 h 26 mn

Isabelle Autissier - PRB - Broken rudder (Cape Town)

Gerry Roufs - Groupe LG

3.

Hervé Laurent - Groupe LG-Traitmat - 114 d 16 h 43 mn

Yves Parlier - Aquitaine Innovations - Broken rudder (Perth)

Pacific Ocean (66th day)

4.

Eric Dumont - Café Legal-Le goût - 116 d 16 h 43 mn

Patrick de Radiguès - Afibel - Electrical problems (New Zealand)

5.

Pete Goss - Aqua Quorum - 126 d 29 h 25 mn

Bertrand de Broc - Votre nom autour du monde - Capsized (Bay of Biscay)

6.

Catherine Chabaud - Whirlpool-Europe2 - 140 d 04 h 38 mn

Tony Bullimore - Exide Challenger - Keel loss (SW Australia)

Thierry Dubois - Amnesty International - Capsized (SW Australia)

Nandor Fa - Budapest - Collision + electrical problems (Les Sables)

Didier Muntuteguy - Club 60° Sud - Dismasted + structural issues (Les Sables)

Raphaël Dinelli - Algimouss - Capsized (SW Australia)

2000-2001 1.

Michel Desjoyeaux - PRB - 93 d 03 h 57 m

Retired

2.

Ellen MacArthur - Kingfisher - 94 d 04 h 25 m

Thierry Dubois - Solidaires - Broken alternator

3.

Roland Jourdain - Sill-Mâtines La Potagère - 96 d 01 h 02 m

Raphaël Dinelli - Sogal Extenso - Collision with a whale

4.

Marc Thiercelin - Active Wear - 102 d 20 h 37 m

Catherine Chabaud - Whirlpool - Dismasted

5.

Dominique Wavre - Union Bancaire Privée - 105 d 02 h 45 m

Patrick de Radiguès - La Libre Belgique - Ran aground in Portugal

6.

Thomas Coville - Sodebo - 105 d 07 h 24 m

Bernard Stamm - Armor Lux-Foies Gras Bizac - Broken rudder and pilot failure

7.

Mike Golding - Team Group 4 - 110 d 16 h 22 m

Eric Dumont - Euroka-Un univers de services - Broken rudders

8.

Bernard Gallay - Voilà.fr - 111 d 16 h 07 m

Richard Tolkien - This Time - Furler failure

9.

Josh Hall - Gartmore - 111 d 19 h 48 m

10. Joe Seeten - Nord Pas de Calais-Chocolats du Monde - 115 d 16 h 46 m

Javier Sanso - Old Spice - Lost rudder Fedor Konyukhov - Modern University for the Humanities - Back problems

11. Patrice Carpentier - VM Matériaux - 116 d 00 h 32 m 12. Simone Bianchetti - Aquarelle.com - 121 d 01 h 28 m 13. Yves Parlier - Aquitaine Innovations - 126 d 23 h 36 m 14. Didier Munduteguy - DDP-60ème Sud - 135 d 15 h 17 m 15. Pasquale de Gregorio - Wind Telecommunicazioni - 158 d 02 h 37 m

2004-2005 1.

Vincent Riou - PRB - 87 d 10 h 47 m

Retired

2.

Jean Le Cam - Bonduelle - 87 d 17 h 20 m

Marc Thiercelin - Pro-Form - Lack of preparation (New Zealand)

3.

Mike Golding - Ecover 2 - 88 d 15 h 15 m

Patrice Carpentier - VM Matériaux - Broken boom (New Zealand)

4.

Dominique Wavre - Temenos - 92 d 17 h 13 m

Roland Jourdain - Sill & Veolia - Keel failure (New Zealand)

5.

Sébastien Josse - VMI - 93 d 0 h 2 m

Alex Thomson - Hugo Boss - Hole in deck (Cape Town)

6.

Jean-Pierre Dick - Virbac-Paprec - 98 d 03 h 49 m

Nick Moloney - Skandia - Keel loss (Brazil)

7.

Conrad Humphreys - Hellomoto - 104 d 14 h 32 m

Hervé Laurent - UUDS - Rudder problems (Cape Town)

8.

Joé Seeten - Arcelor-Dunkerque - 104 d 23 h 02 m

Norbert Sedlacek - Brother - Keel problems (Cape Town)

9.

Bruce Schwab - Ocean Planet - 109 d 19 h 58 m

10.

Benoît Parnaudeau - Max Havelaar-Best Western - 116 d 01 h 06 m

11. Anne Liardet - Roxy - 119 d 05 h 28 m 12. Raphaël Dinelli - Akena Vérandas - 125 d 04 h 07 m 13. Karen Leibovici - Benefic - 126 d 08 h 2 m

BT TEAM ELLEN

© Mark Lloyd/BT Team Ellen

16

BT Team Ellen currently comprises three sailors – Ellen MacArthur, Nick Moloney and Sébastien Josse – but the team as a whole extends far beyond the three principal sailors. They are supported by a team of dedicated professionals - the shore team who ensure all the boats are in race ready mode, the media and communications team who communicate to the public and media about the team’s endeavours, the project management team who ensure the project’s aims stay on course and the back-up team in the office dealing with all the administration. In addition, to the team are the official sponsors and partners whose support allows BT Team Ellen to achieve the objectives they set themselves on and off the water: “It is never just about one person, it is a huge collective effort as a team and without our sponsors we would be nowhere.” Ell e n M a c A rt h u r Ellen MacArthur (GBR) Born: 8 July 1976 Lives: Cowes, Isle of Wight, UK

it’s all about

“With ours and BT’s combined passion for both sport and the world around us, I am convinced that the projects we will be working on together, both on and off the water, will help us to achieve our mutual objectives of not only being able to win races, but to promote the power of communications and technology to help create a better, more sustainable, world. When you sail around the world you have no choice but to be completely tuned into what is around you. How to harness the power of nature and manage the limited resources you are carrying on board. You sail around our planet and realise it’s not so big after all, and that it has it’s own fragility.”

being a

Team

PROFILE Ellen MacArthur first hit the headlines in 2001 after single-handedly racing non-stop around the world in the Vendée Globe at the young age of 24. Then, again, in February 2005 Ellen grabbed the attention of the world’s media when she set a new world record onboard her 75ft trimaran of 71 days, 14 hours, 18 minutes and 33 seconds, becoming the fastest solo sailor around the planet until Francis Joyon broke her record early in 2008. But her career in sailing began at the age of 18 when she sailed single-handed round Britain in 1995. In 1997, Ellen undertook the Mini Transat solo race from Brest to Martinique then in 1998 race a 50ft boat in the solo Route du Rhum transatlantic race finishing fifth overall in the monohulls. Then began the three-year cycle of preparation for solo sailing’s ultimate challenge, the Vendée Globe. Ellen amazed the sailing world by finishing in second place to Michel Desjoyeaux, France’s leading solo sailor. BT Team Ellen combines Ellen’s passion for the sport of sailing – she will be competing in the Archipelago Raid on the BT F18 and the JPMorgan Asset Management Round the Island Race on the BT Extreme 40 in 2008 before competing in some of the BT IMOCA 60 events throughout 2009 - as well as supporting BT’s CSR programme and continuing with her commitment to pursuing and communicating on how to lead a more sustainable life on land. The sustainability subject is one very close to Ellen’s heart and is strengthened by the support and activities of many of the team’s other

©T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen

A L L A B O U T B E I NG A T E A M 1 7

supporting partners including Renault eco2 and E.ON. Ever since the beginning of her career she has been passionate about tackling the issue of how we can use the planet’s natural resources in a more sustainable way. OBJECTIVE To be an ‘agent for change’ helping big businesses find practical and effective ways to help reduce humans’ footprint on the planet. BT EXTREME 40 Nick Moloney (AUS) Born: 5th May 1968 Lives: Saint-lunaire, France and South Coast of Victoria, Australia, married with a baby daughter. “Last year the BT Extreme 40 finished third overall in the iShares Cup Extreme 40 Sailing Series. This was a great result and our initial goal for the year achieved. These boats are awesome to race – short, adrenalin-pumping courses that allow no room for error, all raced within a stone’s throw of the shore. This year’s iShares Cup has been a lot more heavily contested by even more professional teams including America’s Cup defenders, Alinghi.” PROFILE As a junior sailor, Nick achieved great successes at state and national level. By the age of 21 he was swept up into the international ‘A’ league and found himself living in San Diego, USA competing for sailing’s oldest trophy ‘The

Americas Cup’ in 1992 with Challenge Australia and Paul Cayard’s Il Moro de Venezia, and then again in 1995, this time with John Bertrand’s challenger OneAustralia. By 2005, Nick who was on the road to a very successful sailing career, living mostly in the United States of America between 1992-1998 winning most of the worlds classic major International short and long course regattas, had already circumnavigated the globe three times - Volvo Ocean Race 1997-98 on Toshiba; the Jules Verne Trophy in 2002 onboard Orange skippered by Bruno Peyron and with team mate Sébastien Josse; then the solo Vendée Globe 2004/05 - completed in two stages after suffering keel failure on day 80 of the 95 day voyage that put him out of the race. But Nick returned ten months later to Brazil and completed the journey in December 2005. He has also completed 20 transatlantic crossings, winning five transatlantic races both crewed and solo. Nick has held over 10 individual world speed records including the furthest distance travelled in a 24-hour period in a monohull and the outright round the world nonstop speed record. He is also a Guinness World Record holder as the first and still the only person to windsurf non-stop and unassisted across Bass Strait from mainland Australia to the Island State Tasmania in 22 hours and 11 minutes. OBJECTIVE To keep raising awareness regarding environmental issues whilst achieving our objectives on the water under the BT banner.

18

r ace i n si g ht

© T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen

t was a big dream for me. I had always wanted to sail around the world, and the Vendée Globe gave me the chance to do that. I now know that at the time I was quite young, being 24, though then I really did feel like every other skipper out there on the water. It only dawned on me four years later when I went to the Vendée start in 2004, and realized that if I had been competing, I would still have been the youngest entrant… I set out convinced that this challenge would be much harder than I imagined, and once you’re in that state of mind, you’re more ready than ever to accept tough situations. For me that’s the best way of preparing yourself psychologically – to help you deal with the really hard moments that the Vendée Globe inevitably throws at you. It did turn out to be harder than I expected, although that came as no surprise. It may sound trivial, but you can never disconnect from the boat, its noises and movements. If there was one tiny noise that was not normal, I had to find it and I could not contemplate getting any rest before I had identified it. Somehow, I had rediscovered how to reconnect with my instincts, which I feel as human beings we struggle to do anymore. So in that respect, the Vendée helped me to reconnect with a long lost nature… I also noticed that the only type of food I actually felt like eating were milk products, as if I was going back to the most basic instinct, that of a child. The one thing you miss on a boat is not being able to switch off. Sure, you also miss friends and family, but you know it’s only a matter of time before you see them again, the loneliness of the long distance solo racer is something which can be handled, it certainly

© Ellen MacArthur

doesn’t take you by surprise. I’d sailed about 15,000 miles solo in Kingfisher training, not to mention the thousands of miles on other boats. The impossibility of relaxing is another issue, and that more than anything else takes its toll. Living through an experience such as the

“The Vendée Globe taught me how to dig deeper” If the 2000 Vendée Globe revealed the planet to the 24-year old Ellen MacArthur, it also undoubtedly revealed her to the world… She looks back on her first circumnavigation, one of her biggest life-changing experiences.

Vendée Globe certainly makes you more mature, more able to realise what is really important in life, how beautiful the planet is, and what we are capable of. Having been around it, you know it’s also quite small - despite the common perception – and very fragile. Seeing Marion Island (Southern Indian ocean) changed my life. Its beautiful green slopes sparked my desire to communicate just how special our planet is, I wanted to get to know and understand it better, and made a pact with myself to return to the Southern Ocean with a little more time than a fleeting glance of an island between manoeuvres and sail changes. It’s raw, un-humanised, and it’s a natural heritage which my Vendée Globe experience allowed me to discover with my own eyes, and which I took in with all its intensity. The last portion of the race brought a real feeling of sadness, as I knew that my life changing journey was coming to an end. Only in this race had I felt it so strongly, I was

E L L E N M A C A R T H UR

that type of inner resource, and somehow I feel it’s a great chance for me to have learnt how to dig deeper, to go closer to the limits. The Vendée Globe teaches you just that, and it’s something that people rarely experience in modern life.”

Ellen MacArthur © T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen

young people suffering from cancer and leukaemia sailing, I’m working with various organisations to find new solutions for a sustainable way of life, notably where I live on the Isle of Wight. To a certain extent, all this was triggered by my Vendée, so it did change my life… I believe that the most important thing is who you are and your ability to remain faithful to who you are, and a voyage like the Vendée makes you know yourself like no other experience can. I once found myself up the rig having forgotten a part of my climbing equipment - I had to get up there very quickly as I had broken a batten in the mainsail and it got caught in the spreader, it was a total mess. The boat was sailing on the north part of the Kerguelen plateau which is a quite shallow area, and the waves were getting very big. On my way down I couldn’t put my incomplete climbing gear back on - I was hanging from one hand and a loop on the sail, really not a great situation. It was blowing 55 knots, the boat was all over the place and I was getting thrown against the mast. What kept me going was to think about the kids who were following me back in France - prior to the start, I had sailed with a charity called “A Chacun Son Cap”, whose aim was to take kids suffering from cancer out on boats*. Up there I thought ‘I can’t let the kids down’, and that brought me down in one piece. It came really close, but in that type of situation who can you turn to? No one, except for the people who have made a big impression on you ashore, and whose force becomes an inspiration. It’s incredible to realise how far you can push yourself just by digging into Wet ride aboard Kingfisher during the 2000 Vendée Globe

absolutely fine at sea, soaking it in and loving it, not nervous at all, like I had been every single day during my Europe 1 New Man Star. I had won that transatlantic event, and it was great, but I did not enjoy myself as much as I did in the Vendée, which I simply did not want to end. I had trouble coping with the idea of leaving the boat. I had also understood that once I set foot ashore, my life was never going to be the same again - there was a huge media interest towards the end, I was receiving more and more calls from journalists and it seemed pretty obvious that something enormous was about to fall upon me. I was about to lose my anonymity, and that’s when I realised how precious it was. It means a lot of freedom taken away from you, but also adds “weight” to your name and enables you to be heard. In that respect, I think it’s a duty for me to use that weight to do something positive, being a public person I now have the responsibility to try and make a difference. And it’s what I try to do now. Aside from our charity, the Ellen Macarthur Trust which takes

*This inspired Ellen to create her own similar charity, the Ellen MacArthur Trust, now in its 5th year. In 2009, 100 young people in recovery from cancer will sail around the UK as part of The Ellen MacArthur Trust Skandia Round Britain ‘Voyage of Discovery’. The voyage will stop at 20 ports around the UK and the children will visit hospitals and young person’s principal treatment centres, across the UK, who have helped them recover from cancer and leukaemia. w.w.w.ellenmacarthurtrust.org

19

r ace i n si g ht

Nick Moloney, skipper of the BT Extreme 40, took part in the last edition of the Vendée Globe. Former America’s Cup and fully-crewed round-the-world race competitor, the Australian sailor went on to capture the record for the fastest planetary lap in 2002 - a prestigious title he shared with Sébastien Josse, then a crewmate and today a teammate. Nick tells us about how the Vendée Globe changed his life. © Jon Nash/DPPI (All photographs except top left)- © V.Curutchet/DPPI

20

“The Vendée Globe has changed me in so many ways” guess if someone was to ask me what were the best experiences you have ever had at sea, I would answer “In the Vendée Globe”… likewise if I were to be asked the worst experiences I have ever had, then the answer would start with the same “In the Vendée Globe”. At the age of around 17 I desperately wanted to sail around the world solo. In fact, it was the BOC Challenge that originally inspired me as that event used to stop in Australia and regularly made the news. Phillippe Jeantot was the king back then, prior to Christophe Auguin. His boat, Groupe Sceta was the first of these crazy racers that I was to gaze at in amazement in real life. Around this time Titouan Lamazou won the first edition of the Vendée Globe race, and who can forget the incredible race, during which Loïck Peyron performed that crazy rescue of Philippe Poupon when his boat was trapped on her side!!! Amazing! Then it was Alain Gautier and the first race fatality (Nigel Burgess) that just highlighted the danger and

risk that accompanies this event, where the level of difficulty is on a scale that is so high it is tough for many to even comprehend. But I guess it was the 1996-97 edition that really captured my Vendée Globe imagination, the dramatic rescues of Bullimore, Dubois and Dinelli… I will never forget that period when those guys were fighting for their lives in the deep South - headline news in Australia for weeks. I think that’s when the switch really flicked and I said to myself “I am going to see if I can do that race”. From that point I was pretty well devoted to the Dream. Solo sailing was, and I guess still is, the most intriguing discipline in the sport of sailing. I was always asking myself if I really believed that I could sail across the Atlantic or around the world solo… I had to find out! And the Vendée Globe was the ultimate test. Its history is amazing, in every edition something remarkable happened. It is definitely one race here you can never predict the outcome, right to the very end. The extremity makes the race so special to me, in every aspect: the boats,

the sailing skills required, the demand on one’s body with the sleep deprivation… and the mental anguish associated with the stress of high speeds, potential collision with a ship, iceberg, whale, etc. The greatest stress it the high potential of failure… ie to not finish the course. This stress was with me 24/7 for 80 days before my worst fear was realised. Actually to say “my worst fear” here is a bit of a misuse of the phrase...in fact a competitor’s worst fear is to die at sea and in this race there is a far greater chance of such a tragedy than any other yacht race. Prior to the start I was pretty happy, I had great faith in the team and the boat, I had already sailed more than the equal distance of an around the world passage onboard that boat. In the previous three years that I had spent sailing Open 60s and solo sailing in general I had achieved 9 podium placing winning three transatlantic passages along the way so I was confident in our package and that I would be safe and comfortable at sea. I did though have a lot going on in my personal life and I was very afraid

n ick molo n ey

that I would miss the company of loved ones and that I would struggle emotionally. This was difficult to train for and a complete unknown so that was worrying. I am very much a peoples person and love the company of others so you could say that I was afraid of myself and whether or not I would be mentally tough enough to endure potentially 100 days at sea alone. This proved to be a real issue… after day 20 I started to suffer and ponder on how much longer we had to go. As my boat was an older generation I sold myself the mental attitude that this was

simply an adventure and my objective was to just finish... at sea I could not cope with this and day 20 it hit me that I was not competitive and this was going to be a very long tour. From that point I struggled with the solitude and could not find a good rhythm with the boat or myself. Thank God for our BT sponsorship because I made quite a few satellite phone calls after that. There are a lot of memories associated with my Vendée Globe, but above all I would like to thank every person who cheered for us on the day of the start, it was an unbelievable emotion. Then there was that bloody storm in the Indian Ocean… The sea state was so huge and the impact on the boat was so violent that it completely shattered my confidence. I had lost control... I really feared for my life. But I was to experience a fantastic moment when I rounded Cape Horn for the third time shortly afterwards - a pure textbook rounding, with 50 knots of wind and huge but

safe swells, just magical! The worst part of the voyage was still ahead of me, and I eventually lost my keel and was forced to pull out. Looking back, I’m still today very angry about it, but I’m glad it did not happen at the Horn, where my life would have been in real danger, so all in all I’ve been a bit lucky. Yet, the incident put an end to 10 years of efforts and commitment, and this is a very hard one to swallow. I had to finish the journey, so I came back to where I had pulled out 10 month later and sailed the boat to Les Sables d’Olonne… where I received a huge welcome despite the fact we didn’t publicise the event or anything! I was so flattered and the scene was totally unexpected, I was blown away. I reckon this emotionally wrapped up the adventure, it allowed me to avoid somehow the frustration of an unfinished business - sort of. The Vendée Globe has changed me in so many ways… I have always been a very content person but even more so now through that experience. It is strange, I should feel so disappointed but I actually feel very lucky because I had the chance to experience emotions in that race that have only been surpassed by the love I have for my wife and baby girl. When I arrived in Les Sables in December 2005 I received a welcome that I feel was probably better than that if I had of actually arrived as a race finisher. I was so happy and the journey was pure, personal and honest. The Vendée Globe was a 10 year dream that lived with me every minute of these 10 years. Today, not many people get the chance or have the motivation to live out their wildest dreams. During that journey I really felt guilty for the amount of time I had devoted to my career, the weddings I had missed, the ups and downs with friends, simply because I was racing or training towards my next objective or goal, and the Vendée has made me realise how to share my life. It’s the same as anything in life, you can ponder on the bad and spend your days with a frown on your face or you can pick out the good bits and wear a smile straight from a warm and content heart. I am happy with my memories, I am a lucky man in life and in sport. I have seen images that very few people have been blessed to witness, the sunsets, the stars, the sea life, the icebergs, the list is endless. I know all three of us members of BT Team Ellen feel the same way, we’ve all had the good fortune of experiencing those moments, and sharing them as much as we can is a priority. We’ve had the luck to see very rare sights, it is a strong bond between us and it also makes it a duty for us to work towards the planet’s preservation, carrying that message whilst meeting our targets on the racing scene with our partner BT. Nick Moloney

21

T A K I NG O N T H E W O R L D

© T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen

24

“Sail straight down, straight down and straight down. At the first albatross, all there is to do is take a left, and let the wind carry you.”

T A C T I C A L C O UR S E A N A L Y S I S 2 5

Taking on the world Three oceans, three legendary capes, a deceptively simple route… “Sail straight down, straight down and straight down. At the first albatross, all there is to do is take a left, and let the wind carry you. It works just like that”, wrote Alain Colas in 1974, describing his own circumnavigation. And if one can only acknowledge the efficiency and simple elegance of the French sailor’s words, there is no doubt it omits all the conceivable meteorological complexities such a journey implies! If Southern latitudes are what spring to mind when one evokes the “Roaring Forties”, we should not forget that “our” Northern Europe 40s also know how to make themselves heard, notably during the winter when this particular zone of the Atlantic is shaken by westerly disturbances. The Bay of Biscay, where singlehanders entered in the Vendée Globe start their adventure, is famous for its fierce autumn and winter storms, due to low pressure systems generating strong west winds and subsequent treacherous waves. It is thus important to exit that area as soon as possible, anticipating the tricky passage around Cape Finisterre (western Spain) - in terms of trajectory, it can be interesting to get close to the latter, but the area holds a few traps, and in a westerly regime, the risk is to be pushed back into the bay. The descent along Portugal can be rather fast, as was the case in 2004. The strategy then dictates the choice of the most direct route towards the North East Trade Winds, which statistically blow between 10 and 15 knots. Their influence can start to be perceived while approaching the Canary Islands (28° North), whose elevation and coastal characteristics have an effect on local winds - sailors can find themselves in the lee of the islands, up to 60 to 80 miles away from land! South of the Canaries, the options are conditioned by the upcoming crossing of the infamous “Doldrums”, formerly know as “horse latitudes” and more scientifically called Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), where dead calms and sudden squalls or thunderstorms alternate. This oceanic obstacle is a tactically decisive portion of the course, and the best “door” at this time of year lies around 30°W, bearing in mind that the zone itself spreads over approximately 250 miles. The objective is to reach the other side and its coveted South East Trade Winds, the first boat to catch them being able to increase the lead over its rivals. But the dreaded Saint Helena high pressure system and its associated light airs lie ahead, and force the navigators to go West (actually almost turning their back to the logical route) before starting to head towards the South East and the distant Cape of Good Hope. The change of trajectory is generally possible around 30°S, which is the border of the Southern lows’ zone of influence.

T A K I NG O N T H E W O R L D

nce in the roaring forties (the Southern ones this time!) and into the Indian ocean, conditions change for good. Wind picks up, temperatures drop on a daily basis, grey clouds obstruct the sun and waves get rather aggressive… Most sailors describe a hostile and chaotic environment, where caution should prevail. The balance between making the most of the wind’s power whilst keeping a foot on the brakes becomes crucial, and being able to interpret the boat’s “signals” to prevent gear failure and maintain the right pace. The choice of trajectory is obviously conditioned by the possible ice gates that the organiser might put in place - one might remember that compulsory passage points had been implemented in 2004, and the boats also were forced to leave Heard Island (53°S) to starboard. The Pacific Ocean, which officially starts when crossing the longitude of South Tasmania, generally welcomes the sailors with a “tidier” sea state. Taking advantage of the long swell, Open 60s can pile up miles and display flattering 24-hour runs. But that should not hide the fact that if these conditions indeed are much more frequent than in the Indian Ocean, the Pacific is nonetheless potentially violent, swept by lows that travel around the “Furious Fifties”. Those systems are generated by the collision of cold air making its way from Antarctica and relatively warm waters coming

One thing is certain, for the past 4 or 5 years, icebergs have made their way further North in the Pacific Je an-Yves Ber not, We ather specialist and successful rou ter

from the North. The important speed at which these complex systems move towards the East is due to the fact that no land stands in their way. It also explains the formation of considerable wave heights, and this extreme scenario exposed by Eric Mas (Meteo Consult) would frighten even the most seasoned circumnavigator: “A Force 11 storm accompanying a swell for 72 hours generates a significant wave height of 20 metres.” Cape Horn naturally represents one of the journey’s most important moments, both symbolically and tactically. The southernmost rocky tip of the American continent, contrary to the other two great capes, is actually rounded very close to the shore – no need to lengthen the route at this point! Back in the Atlantic, the first question that may arise depending on the weather

conditions could be where to leave the Falkland Islands – starboard or port? The going can get very tough there, and that choice will also be made in conjunction with the overall strategy for sailing back up the Atlantic. Generally, and in order to stay clear of the St Helena High once more, sailors choose to remain close to Brazil, since the wind pressure is statistically better in that area. This route is also favourable when it comes to positioning the boat for the second ITCZ crossing: by the time the crews reach it on their way back, this zone will have had enough time to creep slowly to the South, and will have to be tackled slightly further West. Finally sailors know that if their return to the North Atlantic means “home soon”, the conditions are likely to remain demanding, since the disturbed southwesterly breeze is still very active in early February. Weather specialist and successful router Jean-Yves Bernot has worked with Sébastien Josse prior to the Vendée Globe. He gives us his views regarding that 6th edition of the round-the-world singlehanded non-stop race. “One thing is certain, for the past 4 or 5 years, icebergs have made their way further North in the Pacific, but as far as determining if this is a durable tendency or a punctual phenomenon, the question remains open. But it will certainly have an effect on the course since one © J. Vapillon

26

© B.de Broc/DPPI

T A C T I C A L C O UR S E A N A L Y S I S 2 7

©Benoit Stichelbaut

Sullen skies, ferocious waves and surreal sunlight, captured by Bertrand de Broc in the Southern Ocean (1997)

The entrance to Les Sables d’Olonne

can expect the race organisers to put ice gates in place rather high in latitude. This of course changes strategic choices, since it is not quite the same to be able to dive to 60°S or to be confined to 56°S or higher… but there’s no questioning the absolute priority given to safety. I work with sailors from the Pôle Finistère Course Au Large (Ed note - Brittany-based offshore training centre), many of whom are very experienced racers with one or more circumnavigations under their belt - which is the case for Sébastien Josse. I have put together a very comprehensive road book totaling roughly 1000 pages, and also given out little animations illustrating “classic” strategic moves, which they can examine and use while at sea. I think it’s good for them to be able to rely on those tools, which I constantly improve by adding new

elements gathered on the race track, either by myself or the skippers I route from ashore. It is obvious that the boats have made huge progress in terms of power, average speed but also stability of trajectory - a factor the designers have been very keen to improve. During the past 3 or 4 years, the autopilots have also taken a massive step forward, modern IMOCA 60 footers are very fast under pilot and the singlehanders can thus spend more time working at the nav station whilst relying on this assistant. I would say that today’s average speeds are equivalent to the top speeds we were seeing 4 years ago… which gives an idea of the leap forward. Compared to the 2004 edition, that had benefited from favourable conditions during the descent towards the Equator, I think that the new generation of

boats can gain two to three days around the world. Of course, these monohulls have become more demanding both physically and mentally, and it seems clear to me that the guys who have a previous multihull experience have an advantage, since they learnt how to react quickly, to handle speed at the related stress.” Undoubtedly, Sébastien’s maxi-catamaran RTW adventure in 2002 - capturing the Jules Verne in Bruno Peyron’s crew alongside BT Team Ellen teammate Nick Moloney - has already proven valuable experience. It is also worth reminding that Josse tackles, with this 2008 Vendée Globe, his fourth circumnavigation… his background is among the most impressive in the fleet. Jocelyn Blériot

28

SÉBASTIEN JOSSE

A D ay i n t h e lif e o f

Sébastien Josse

On deck I spend most of my time in the cockpit, which amounts to roughly 10 hours out of 24. While up on deck, I don’t helm a lot, I mostly trim the sails, perform regular checks to spot weak points and gear fatigue. On a round-the-world journey, there are not a lot of tacks or gybes, maybe only 20 during the whole race! While in the cockpit, I mostly keep the sailplan adapted to the wind strength, in order to optimise the speed at all times. The most tiring and difficult manoeuvre is to bring the huge (400 square metres, the equivalent of 1.5 tennis courts) spinnaker down. You need to recover it quickly and cleanly because if it falls into the water it can pull on the rig and potentially generate a lot of damage.

29 © T. Martinez/Sea & Co/BT Team Ellen (All photogaphs, this feature)

2 4 ho u r s o n boa r d

Navstation

Sleeping

This is where I sit to work out my strategy, get my weather information, answer calls from the race HQ and also chat with my friends and family. I roughly spend 4 hours out of 24 down there, but of course that figure rises if the weather situation is not clear and I need to spend more time assessing various scenarios. I download 4 weather files per day, as there is a new one issued every 6 hours. I also send pictures and videos back to my shore base - editing a video takes about 1.5 hours - and I usually make one private phone call a day, to my partner, family or close friends. One last detail: I have a little fan mounted on the top of the instruments panel, because coming down straight from a manoeuvre, very hot and a little sweaty to sit down in front of a screen tends to make me a bit nauseous.