19 minute read

CHAPTER.02 // Towards a Definition of Soft Architecture

Towards a Definition of Soft Architecture

The chapter introduces the different fields which pose as a background to the topic of soft robotics in architecture, which will hereafter in the work be entitled the compound name “Soft Architecture”. Each of the relevant topics will be described with some important definitions and notable case studies mentioned, with the scope of forming a common platform of knowledge from which pursuits for an architectural application can be undertaken.

Advertisement

abstract

KINETIC

adj., of, relating to, or resulting from motion.

AUTOMATIZATION

automatic; adj. (of a device or process) working by itself with little or no direct human control.

INTERACTIVE

adj. responding to a user’s input.

RESPONSIVE

adj. readily reacting or replying to events or stimuli.

S O F T

INFLATABLE

“An inflatable is an object that can be inflated with a gas, usually with air, but hydrogen, helium and nitrogen are also used. One of several advantages of an inflatable is that it can be stored in a small space when not inflated, since inflatables depend on the presence of a gas to maintain their size and shape.”

(Topham, 2002)

The problem of designing and controlling a soft-robotic system requires knowledge from many areas including biomechanics, compliant control, smart materials and flexible robots (Sanan, 2013).

Before initiating the exploration of how to apply soft robotic technologies into an architectural practice it is important to clarify preceding knowledge which is considered as a base of the actual research.

Areas of study such as inflatable systems, kinetic and responsive technologies are to be summarised in this chapter together with main definitions from the field of soft robotics, approximating a path towards a new paradigm of bio-inspired design.

figure 2.1

Scheme - areas of knowledge and their intersection, constituting the definition of pneumatic, Soft-Architecture.

(A)

(B)

figure 2.2 Diagram: air-inflated (A) vs. air-supported (B)

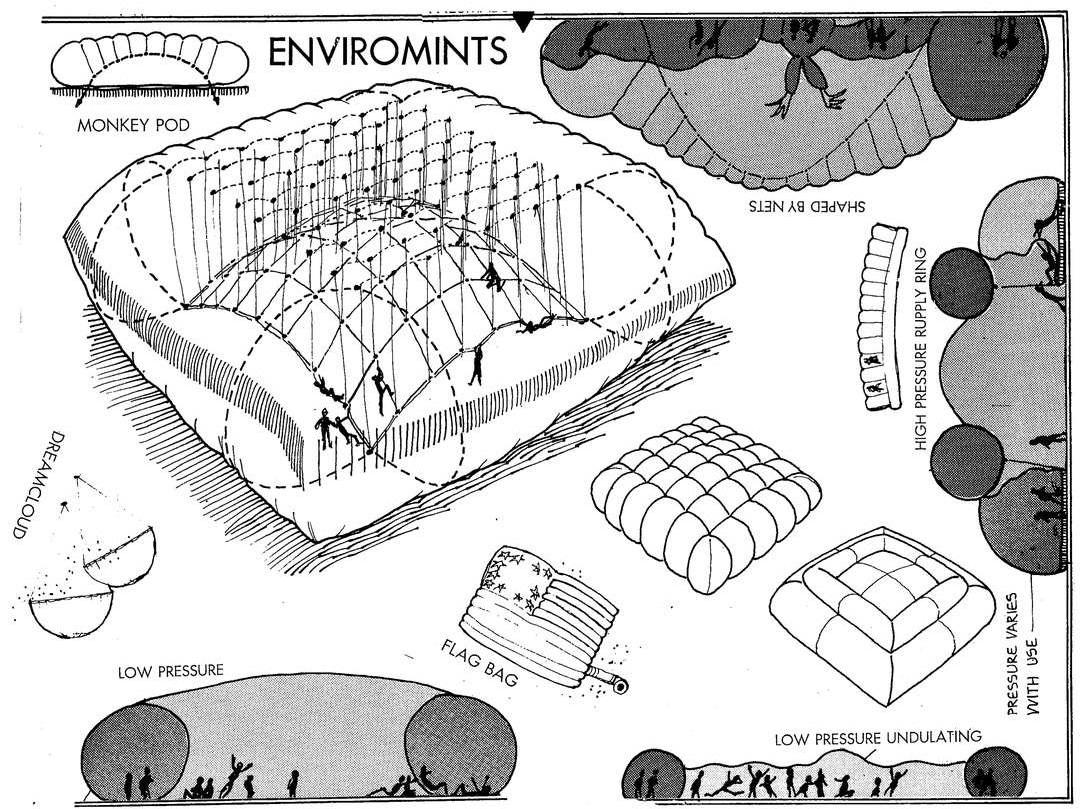

2.1 INFLATABLE ARCHITECTURE

The term ‘inflatable’ origins in the latin language, where the word inflare means to blow into, to pump. Inflatable structure is the pliable-walled structure that can be filled with air and maintains its size, shape and strength due to internal pressure (Graczykowski, 2011) - it is made by using membrane material (can only hold tensile stress). Such structures are a special case of a class known as membrane structures. Based on the method of pressurization, inflatable structures using air can be classified as either air supported or air inflated (Figure 2.2). Air supported structures commonly utilize a small pressure differential between internal and external pressure and are continuously replenished with air as they are usually open structures - inflatable roofs and other inflatable structures used in entertainment. (Sanan, 2013) Air inflated structures, on the other hand, usually consist of pressurized air only within the walls of the structure, and not in the occupied space itself, thus eliminating the need for airlocks at access points (in the case of buildings) and requiring less power to pressurize a relatively much smaller volume of air. some examples of commonly used air inflated structures are temporary buildings and pavilions used for military and entertainment, but also vehicles such as airships and boats, emergency equipment such as escape slides and even toys and furniture. (Onate and Kroplin, 2005)

Inflatable architecture has been around for at least 40 years. In this way, architectural design becomes truly portable. It can eventually fit into a shopping bag, be made smaller or larger. Inflatables have aided technological and other advances and are often used as temporary structures for specific occasions, despite the several disadvantages, namely its durability or wastefulness.

Since the 1960’s many projects have used air as a medium for shaping enclosures. The idea began in that decade - design by American firm Jersey Devil (Figure 2.4) or by Ant Farm - outdoor installation Cadillac Ranch in 1970 - the most prolific at that time, gearing several projects (Figure 2.5). Those early important inflatables created as “happenings” to host temporary events, standing in contrast with their urban contexts, in between of the classical materials like the stone, glass and grass. On the other hand, later in 1998, the artist Michael Rakowitz attempted to fuse the inflatable with the existing in his project of ParaSITE. Originally intended as a critical joke about the waste products of human inhabitancy, Rakowitz was using the HVAC exhaust from buildings to inflate a temporary heated shelter structure for the homeless (Figure 2.6).

With development of CAD systems and robots came also the ability to cut more precise and complex envelope shapes. Alexis Rochas, an architecture professor at SCI-Arc, created an installation in 2006 (Figure 2.7). He had the idea that in the future we will pack our homes into a regular suitcase, and so he transported his installation over a period of six weeks to different locations to host a variety of functions. Another digitally fabricated notable example is by Kengo Kuma (2005) who created a modern, air inflated form of a traditional japanese tea house on the grounds of a museum in Frankfurt (Figure 2.3).

figure 2.3 Kengo Kuma “Tea Haus” , Museums für Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt, 2005

figures 2.4-5 Jersey Devils,; Inflatables (up) and Ant Farm; Clean Air Pod (down)

figure 2.6-7 Michael Rakowitz, paraSITE inflatable shelter (up) and Aeromads - a movable environment by Alexis Rochas (down)

2.2 KINETIC ARCHITECTURE

Kinetic (adj.) “relating to motion,” 1841, from Greek kinetikos “moving, putting in motion,” from kinetos “moved,” verbal adjective of kinein “to move” (Harper, 2015).

The concept of kinetic architecture follows a path where buildings are designed in order to allow parts of the structure or envelope to move, without compromising overall structural integrity. A building’s capability for motion can be used to enhance its aesthetic value, respond to environmental conditions, and perform functions that require an easily adjustable, alternating solution, which would be impossible for a static structure (such as blocking and opening an accessway).

The possibilities for practical implementations of kinetic architecture, or rather, the automized mobilization of larger, more significant building components, increased rapidly in the late 20th century due to technological advances in mechanics, electronics, and robotics (Zuk, 1970). In his 1970 book “Kinetic Architecture”, William Zuk inspired a new generation of architects to experiment and design a broad variety of functioning kinetic buildings. Since the 1980s, thanks to the introduction of new concepts, such as Fuller’s Tensegrity, and by the commercial widespread of robotic systems, kinetic buildings have become increasingly common internationally and in daily use (Salter, 2011).

figure 2.8 Burke Brise Soleil at the Milwaukee Art Museum, Santiago Calatrava, 2001

Examples of such kinetic systems put in use in buildings vary from very small component size (usually at a residence environment) to a very large scale (such as for entire building portions or large infrastructural solutions- in the case of kinetic bridges (Figure 2.9), providing solutions to every-day building usage patterns (such as automatic gates, doors, windows and shutters, and even some transport means which are building incorporated as elevators and escalators), or on a special event scale (such as retractable roofs at stadiums).

Some other, more specific themes of kinetic structures that could be distinguished by the early 21st century are fantastic structures, which make use of kinetic properties primarily for the sake of aesthetic awe inspiring, such as Calatrava’s bird-like Burke Brise Soleil at the Milwaukee Art Museum (Figure 2.8) and the “living skin” theme, which groups together a growing attempt to turn building envelopes into a kinetic element that is able to transform and adapt to varying conditions and needs, as in the way of living organic skins (Salter, 2011).

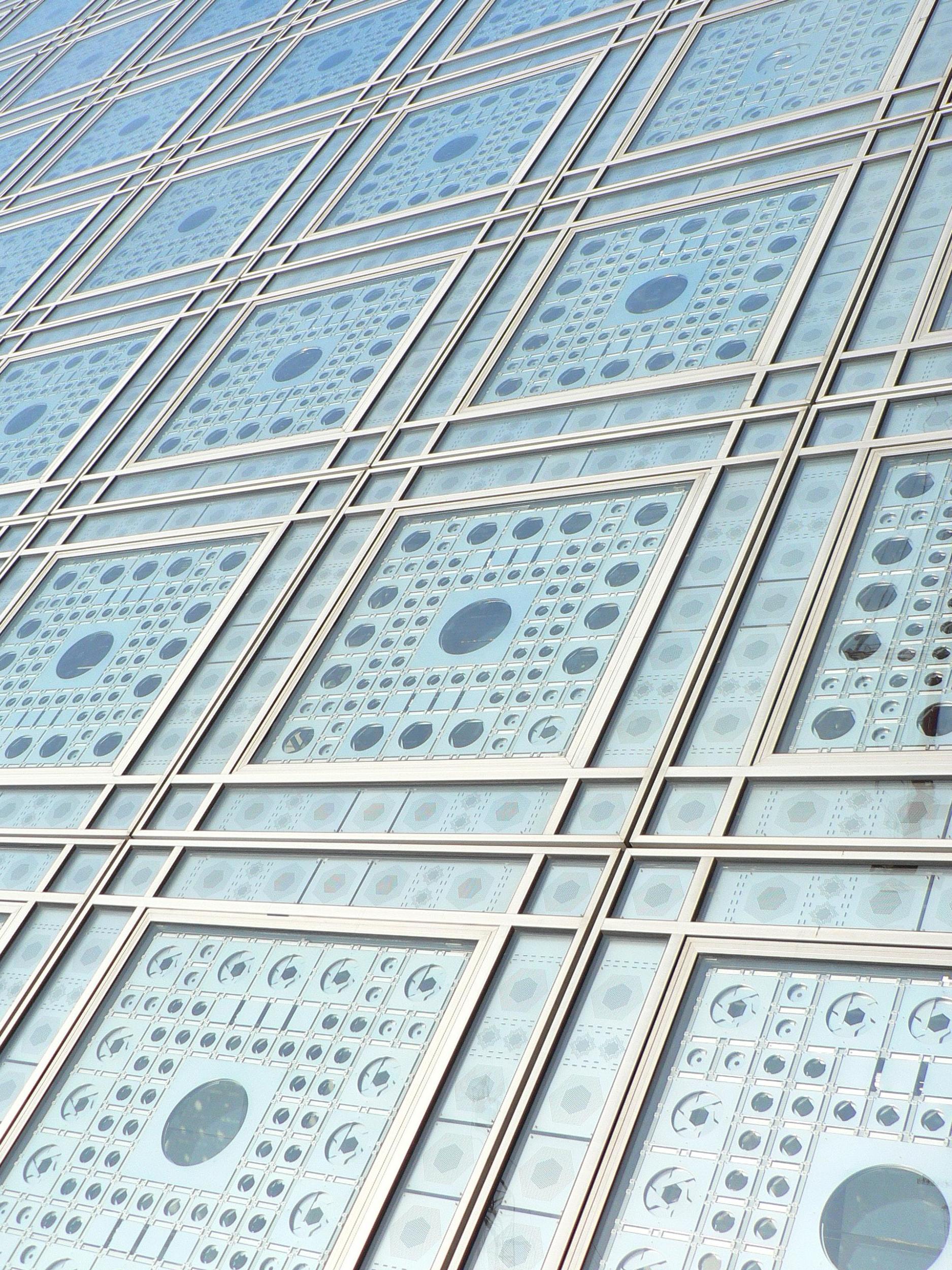

A well-known early example for such a kinetic building skin system is Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde Arabe, which features a photo-responsive shutter system inspired by the Islamic Mashrabiya (Figure 2.10).

figures 2.9-10 Lake Shore Drive Bridge, a double-leaf bascule bridge constructed in Chicago 1937 (up), and the kinetic facade at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, Jean Nouvel, 1987 (right)

2.3 SMART ARCHITECTURE

Although AT&T introduced the “intelligent buildings” concept already in 1982 (Graham and Marvin, 1996), much of the research and development work in this important area is still in its infancy.

A degree of automation provided by kinetic systems was emerging in last decades thanks to the IT industry fast development. This trend is going beyond mere automation, embracing complex cybernetic processes (the science of control and communication in animals, men and machines) and learned behaviors. Previously to be purely technical, theoretical or predominantly environmental camps have merged and begun to share their concerns under the rubric of smart architecture. (Senagala, 2005)

How could we frame the general direction of the mentioned above development? How can we define the difference in making architecture mechanically and computationally intelligent? What does it mean for architecture to be called “smart”?

The main outline of framework for smart architecture connects important conceptual, technological and architectural developments in this direction. We could use the term smart in order to group together all the advanced technological solutions coming from kinetic architecture such as the following fields sometimes referred to as responsive, performative, interactive or adaptive architecture.

figure 2.11 The Al Bahar Towers dynamic external screen, opens and closes in response to the movement of the sun, Aedas, Abu Dhabi, 2012

2.3.1 Interactivity, Responsivity

On one hand, across the many fields touched by interactivity (information science, computer science, human-computer interaction, or industrial design, communication) there is still little agreement over the meaning of that term. In computer science, interactive refers to software which accepts and responds to input from people, for example, data or commands. (Sedig, Parsons, Babanski, 2012)

On the other hand, responsivity differentiates itself from interactive design by not limiting itself to human induced input. Unlike mere interactivity, responsiveness does not require human gesture to take place, and is equipped with the sensibility and set of algorithms to perform on its own.

figure 2.12 Recompose, an interactive system for manipulation of an actuated surface, MIT Media Lab, 2011

Although low-tech systems that make use of physical mechanism or properties of materials could be considered responsive by certain terms, The main focus of the field is usually dealing with electronic configurations, which allow much greater flexibility of operation.

Since interactivity could be regarded a branch of responsivity, common features could be drawn for both kind of electronic systems. It could be generally stated that any interactive or responsive system require a set of essential elements including: a mean of input (e.g. buttons, sensors, cameras), a mean of output (or the manipulated object e.g. light, sound or matter) and a computer or a microcontroller, pre or continuously equipped with a set of algorithms (a program) to bridge between the manipulator source and the manipulated target (Figure 2.14).

Responsive architecture attempts to incorporate intelligent and responsive technologies into the core elements of a building’s fabric. The term “responsive architecture” was originally

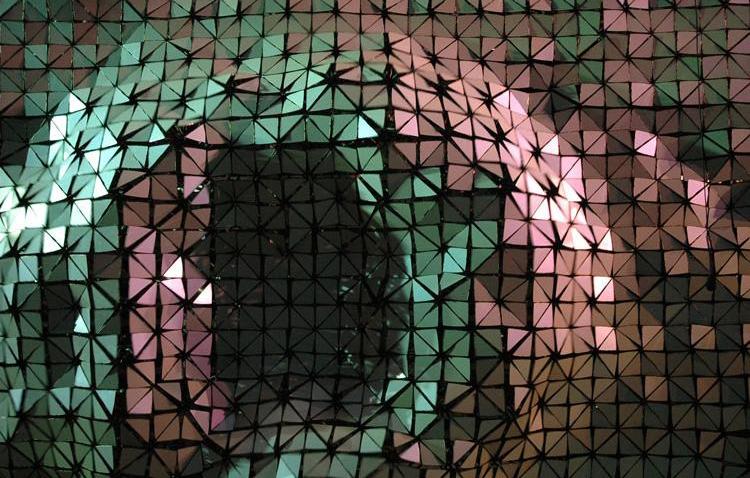

figure 2.13 Aegis Hyposurface, a faceted metallic surface that deforms as a real time response to electronic stimuli from the environment, dECOi, 2001

used by Nicholas Negroponte during the late 1960’s at a time when spatial design problems were being explored by applying cybernetics to architecture. Negroponte suggested that responsive architecture is the natural product of the integration of computing power into built spaces and structures, and that better performing, more rational buildings are the result. (Sterk, 2009)

It is an evolving field of architectural practice as well as a field of research. With the introduction of responsive technologies into the structural systems of buildings, architects have the possibility to optimize the shape according to the different parameters coming from the environment (Grünkranz, 2010). It measures actual environmental conditions (via sensors) to enable buildings to adapt their form, color or character responsively (via actuators or other executive devices). Investigation in the field of responsive systems has potential to design with possibility of adaption to the future unforeseen requirements (Basterrechea, 2012).

Some core examples of interactive environments include systems that allow for human aided direct manipulation of physical objects, surfaces and spaces. For example, many projects have used a voxelized grid of elements in order to be pushed or pulled by human gestures (see MIT Media Lab ‘s Recompose, Figure 2.12, or the Dynamic Reconfigurable Theatre Stage by Laval’s Robotics Laboratory and LANTISS).

Since Negroponte’s results, many working examples of responsive architecture have emerged (a noteworthy example for that is the dynamic facade of the Al Bahar tower in Abu Dhabi, Figure 2.11), but not only in a functional way - also as an aesthetic creations or systems that could allow spatial transformations directly at architectural scale. Such example we can find in the works of Diller & Scofidio (Blur), dECOi (Aegis Hyposurface, Figure 2.13) and NOX (The Freshwater Pavilion, NL).

INPUT SENSOR COMPUTER OUTPUT

figure 2.14 A diagram showing the essential elements of any electronic responsive system,

2.4 ROBOTICS

Robot: origins in Czech language, derived from word “robota” which means to work - ‘forced labour’. The term was coined in K. Čapek’s play R.U.R. ‘Rossum’s Universal Robots’ (1920). (Zunt, 2007)

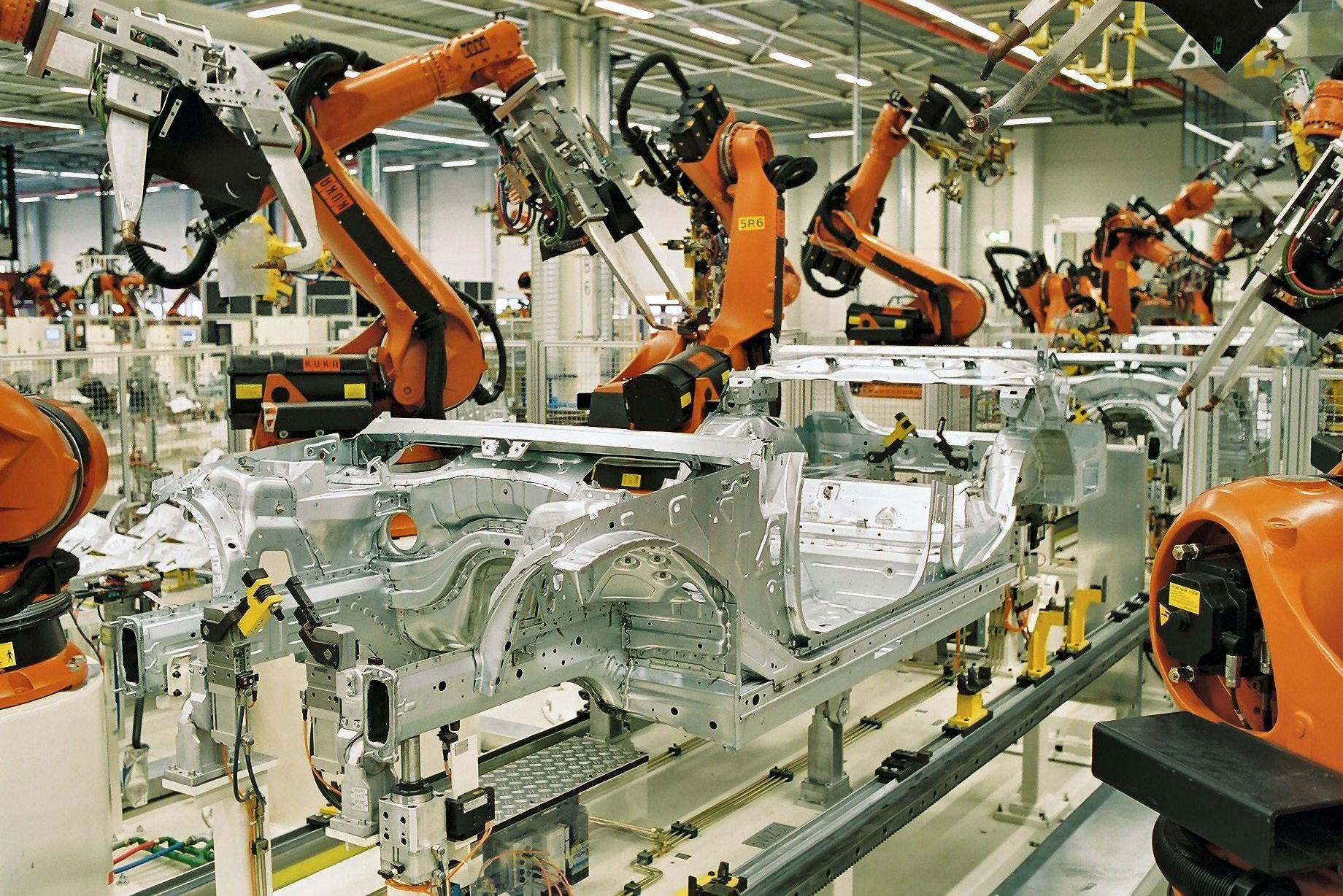

Over the last century robots, or automated machines, entered into our lives at an increasing rate, bringing with them significant transformations into our industries and lifestyle, arguably with positive effects. The main advantages of automation is in saving labor, energy and materials and performs with better quality, accuracy and precision (Aramburo and Trevino, 2008).

The industrial sector has seen the most integration of robotic systems with the automation of production lines in factories, to the point that nowadays, many of the tasks that were considered too delicate or complex for a machine could be accomplished by a generic industrial robotic arm that could be easily adapted to perform an array of tasks that used to be manual such as handling, assembling, screwing and welding (Figure 2.15). Robotic Arms of the kind in recent years have stepped outside the industrial realm with applications in transport, construction and even entertainment (Kuka 2015).

However the construction or domestic sectors are still left relatively behind. Widespread adoption of robotic technologies within architecture would likely have a major impact on the field, both in how the built environment is constructed and in the way it performs. It is important to continue in the investigation of its compatibility with human natural environments, Nevertheless lack of interdisciplinary knowledge is possibly the main obstacle for designers in adopting robotic technologies into buildings.

Robots are usually rigid machines. Design is following the aim in order to perform a small set of tasks in an efficient way. Adaptation in robotic operation is usually achieved by the software layer, which adds a burden on control systems and planners. (Onal, Rus, 2012)

figure 2.15 KUKA robotic arms spot welding in the automotive industry

There has been some prior research in combining robotics and Architecture. In his book “e-topia” Mitchell claims that in the near future our buildings will become robots for living in (Mitchell 2000). Most efforts have concentrated on either adding sensory / computational elements to existing buildings - smart architecture (Johanson, Fox, Winograd, 2012), or introducing self-contained robots into existing spaces (Siciliano, Khatib, 2008).

The second approach may appear as a more natural way to introduce robotics into Architecture. However, after all considerations it could be regarded more of a practical approach to involve a tighter coupling of the fields, in the sense of including robotics via (re)programmably moving the mass that forms the core shape of the environment (Kapadia, Walker, Green, Manganelli, 2010). Several researchers have developed projects considering aspects of “robotic environments”- for example Oosterhuis and his real-time configurability in programmable pavilions (Oosterhuis, 2003).

figure 2.16 A PneuNet gripper by Cambridge Soft Robotics, 2014

2.4.1 SOFT ROBOTICS

Robotics has grown exponentially in the last fifty years and robotic technologies are today very solid and robust, in the accurate, fast, and reliable control of robot motion. Almost all the theories and techniques for robot control, fabrication and sensing, which represent an incredible wealth of knowledge, are based on a fundamental assumption and conventional definition of robots: a kinematic chain of rigid links. Recent advances in soft and smart materials, compliant mechanisms and nonlinear modelling, on the other hand, have led to a more and more popular use of soft materials in robotics worldwide. This is driven not only by new scientific para-

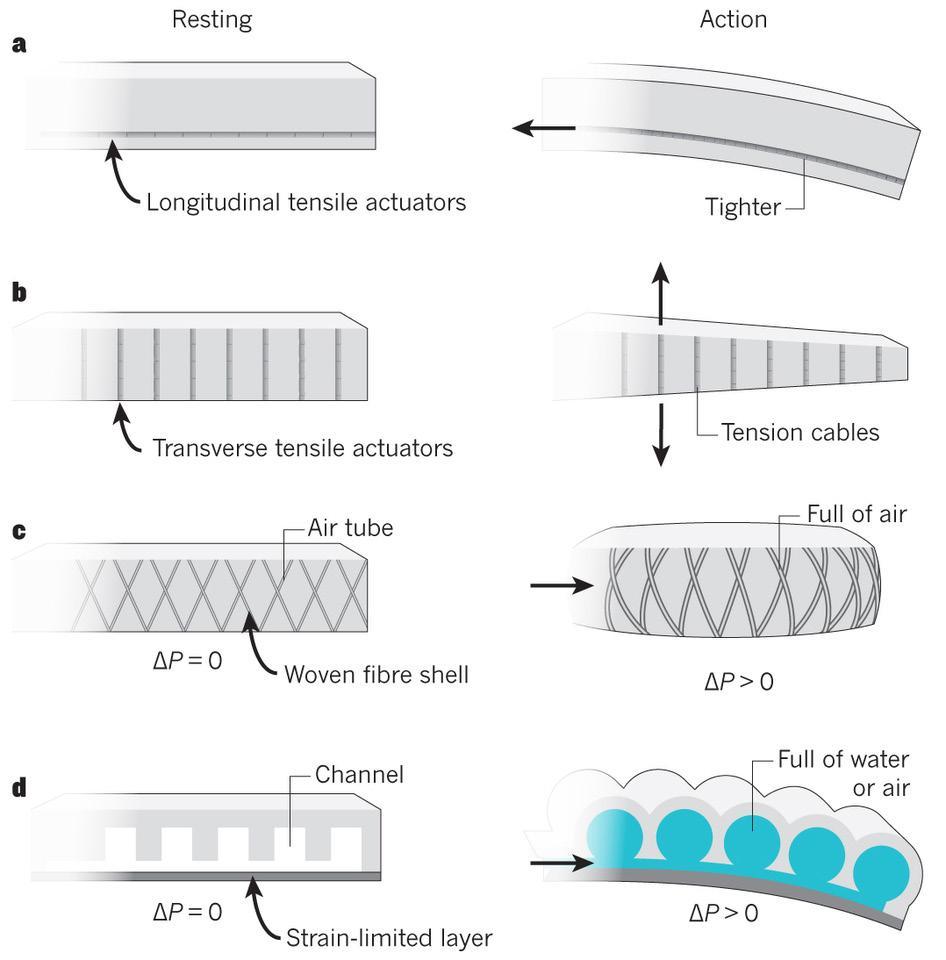

figure 2.17 Cross-section of common approaches to actuation of soft-robot bodies in resting (left) and actuated (right) states. Nature, 2015

digms (biomimetics, morphological computation, and others), but also by many application requirements (in the fields of biomedical, service, rescue robots, and many more), because of the expected capability of soft robots to interact more easily and effectively with real-world environments (Mazzolai et al., 2012; Pfeifer et al., 2012).

Soft robotics is a morphological class of bioinspired robotics. As such, it is greatly drawing it’s inspiration from animals such as octopus or starfish. It’s core concept is to fabricate a robot all made up of flexible and elastic components to grant it with the ability to change gaits easily and maneuver in very limited spaces. We can characterize it as a new research area in the field of developmental robotics, which encompasses flexible structures, control and information processing. In this context soft robotics refers to systems based on the use of shape changing materials and their composites, which generate shape memories and elasticity states (Yokoi, Yu & Hakura, 1999). A variety of typologies of soft robotic actuators were developed, using different actuation mechanisms (e.g. pneumatic actuation, mesh geometry, electroactive polymers) yet all characterized by the use of soft components (Figure 2.17). Among these some of the more prominent are the PneuNets bending actuator (to be thoroughly discussed in chapter 4), fiber-reinforced actuators, pneumatic artificial muscle, dielectric elastomer actuator and multi-module manipulator (De Falco et al. 2014).

Moreover, it is valuable to mention some new methods and technologies which were developed to integrate into soft-robotic actuators and could extend their applicational range such as elastomer embedded 3d-printed sensors (Muth et al. 2014) and microfluidics to change color or opacity of the actuator (Figures 2.18, 2.19).

figure 2.18, 2.19 A three-layer strain and pressure sensor 3d-printed in a stretched elastomer, Harvard University, 2014 (left) and a microfluidic color-changing soft robot, S. Morin, Harvard University 2012 (right)

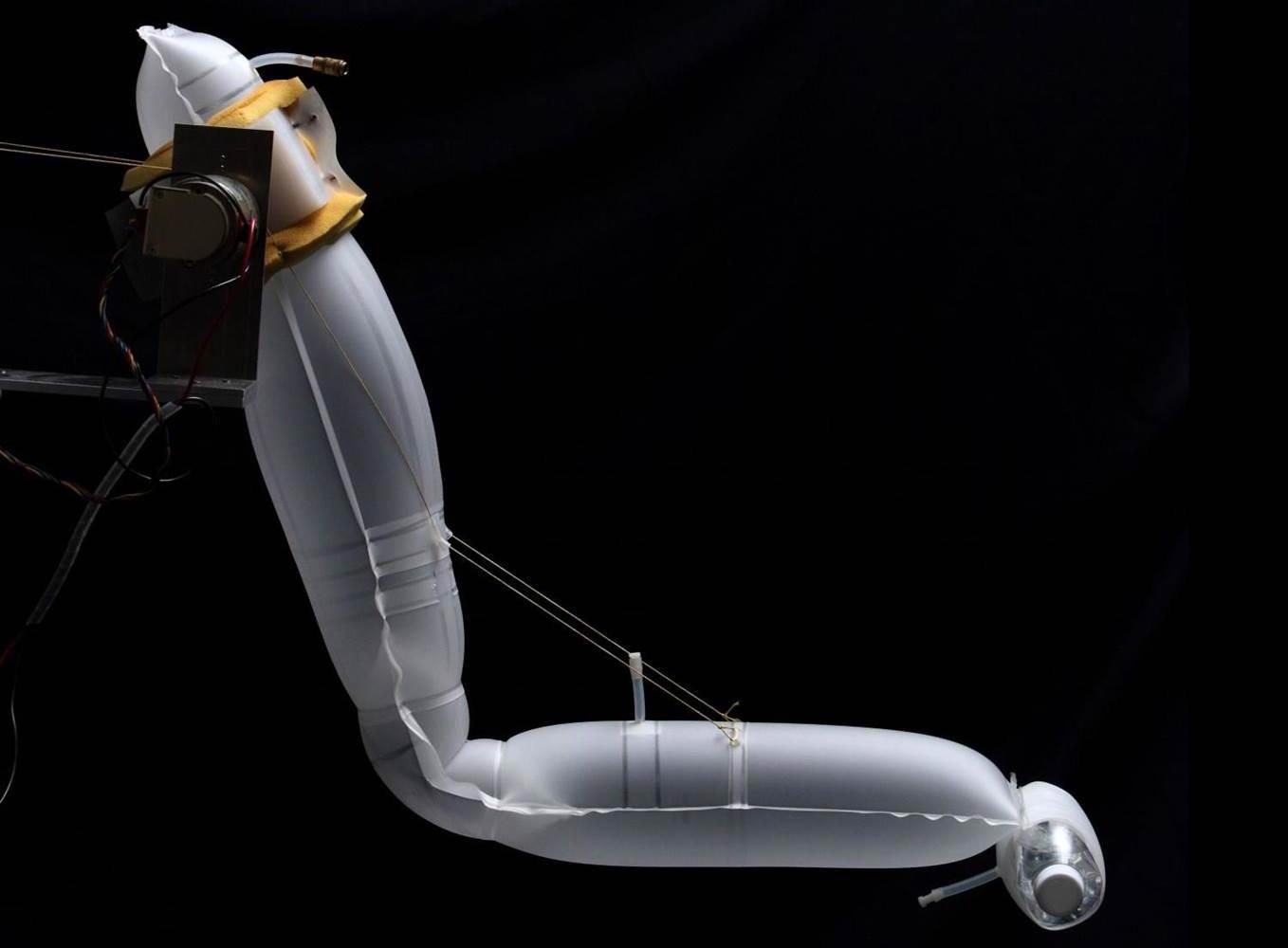

Application areas of practical soft robotic mechanisms include artificial muscles, medical robotics, biomimetic robotics, conformal grippers for pose-invariant, shape-invariant and delicate grasping (Figure 2.16), and human interaction or human assistive technologies (Figure 2.20). (Trivedi, Rahn, Kier, 2008)

figure 2.20 A soft robotic arm, proposed as a part of a future humanoid caregiver. Siddharth Sanan, CMU’s soft robotics lab, 2014

REFERENCES

Topham S (2002) Blow Up: Inflatable Art, München, Prestel Verlag

Graczykowski C (2011) Inflatable Structures For Adaptive Impact Absorption. Warsaw.

Graham S, Marvin S (1996) Telecommunications and the City. Electronic Spaces, Urban Places. London, Routledge

Grunkranz D (2010) Towards a Phenomenology of Responsive Architecture, The University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

Harper D (2005) Online Etymology Dictionary, as accessed on September 5th 2015, websource: www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=kinetic.

Johnson B, Fox A, Winograd, T (2002) Inventing wellness systems for aging in place, IEEE Pervasive Computing, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 67–74

Kapadia, Walker, Green, Manganelli (2010) Architectural Robotics: An Interdisciplinary Course Rethinking the Machines We Live In. Part by an NSF grant IIS-0534423 - the Department of Electrical & and Computer Engineering, Clemson University, Clemson, p. 1

Onal C, Rus D (2012) A Modular Approach to Soft Robots, The Fourth IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics Roma, Italy. June 24-27, 2012.

Oosterhuis, K (2003) Towards an E-Motive Architecture, Birkhauser Press, Basel, Switzerland.

Salter C (2011) Entangled: Technology and the Transformation of Performance, MIT Press, pp. 81–112.

Sedig K, Parsons P, Babanski A (2013) Towards a characterization of interactivity in visual analytics, Journal of Multimedia Processing and Technologies, Special Issue on Theory and Application of Visual Analytics 3 (1): 12–28, Retrieved July 29, 2015.

Siciliano B, Khatib O (2008) Springer Handbook of Robotics, Chapter 55: Robots for Education, pp. 1283–1301.

Sterk T (2009) ‘Thoughts for Gen X— Speculating about the Rise of Continuous Measurement in Architecture’ in Sterk, Loveridge, Pancoast “Building A Better Tomorrow” Proceedings of the 29th annual conference of the Association of Computer Aided Design in Architecture, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Senagala M (2005) Kinetic, Responsive and Adaptive: A Complex Adaptive Approach to Smart Aechitecture.

Zuk W (1970) Kinetic architecture, Reinhold

Zunt D (2007) Who did actually invent the word “robot” and what does it mean?, The Karel Čapek website, Retrieved 11-09-2015.

Trivedi D, Rahn C, Kier W, Walker I (2008) Soft robotics: Biological inspiration, state of the art, and future research, Advanced Bionics and Biomechanics, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 99–117

Yokoi H, Yu W, Hakura J (1999) Morpho-functional machine: design of an amoebae model based on the vibrating potential method, Robotics and Autonomous Systems 28, pp. 217-236

Mazzolai B, Margheri L, Cianchetti M, Dario P, Laschi C (2012) Soft-robotic arm inspired by the octopus: From artificial requirements to innovative technological solutions, pp.338-339

Pfeifer R, Lungarella M, Iida F (2012) The challenges ahead for bio-inspired soft robotics, Commun, ACM, 55(11), pp. 76-87

Onate E, Kroplin B (2005) Textile Composites and Inflatable Structures, p. vii

Mitchell W (2000) e-topia, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Aramburo J, Trevino A (2008) Advancements in Robotics, Automation and Control, InTech.

Kuka Industrial Robots (2015) Kuka Industrial Robots - Robocoaster, Kuka Industrial Robots, Retrieved June 12, 2015.

Falco I, Cianchetti M, Menciassi A (2014) A Soft and Controllable Stiffness Manipulator for Minimally Invasive Surgery: Preliminary characterization of the modular design, IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society.

Muth J, Vogt D, Truby R, Menguc Y, Kolesky D (2014) Embedded 3D Printing of Strain Sensors within Highly Stretchable Elastomers, Advanced Materials, Volume 26, Issue 36, September 24, 2014, Pages 6307–6312