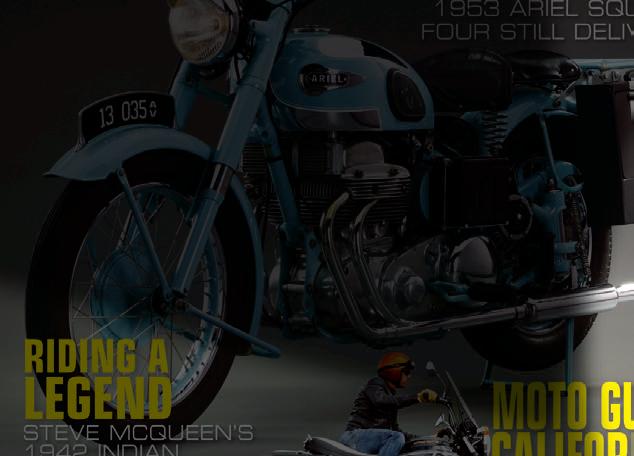

RIDE `EM, DON’T HIDE `EM MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS • SPECIAL COLLECTOR EDITION • STREET BIKES OF THE '60S $6.99 • Special • Display Until Oct. 31

4 BLACK SIDE DOWN

The editor speaks.

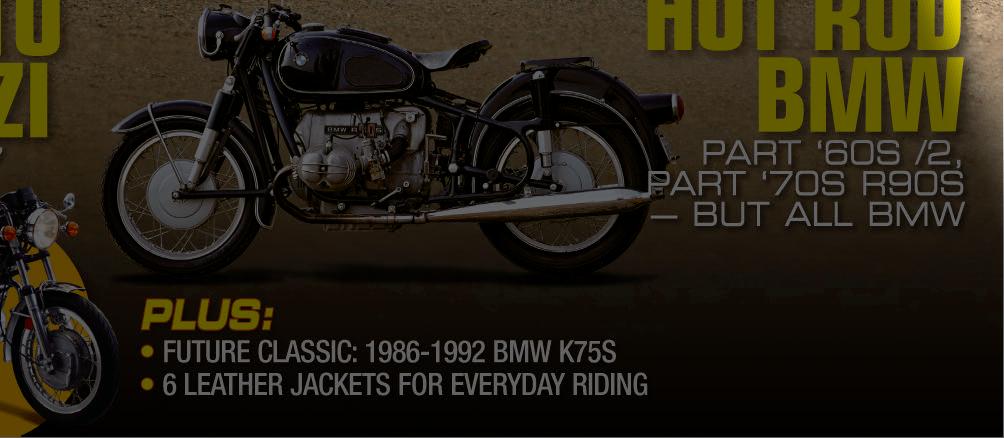

6 HOT ROD BSA: 1967 SPITFIRE MARK III

In the 1960s, BSA was known for flashy bikes with bright colors and lots of chrome, but there was more to the English import than just shine.

12 DREAM MACHINE: 1966 HONDA CA77

All dressed up in angular sheet metal, the Honda Dream is instantly recognizable as a machine of the 1960s.

18 VELOCETTE THRUXTON: TWO FISHTAILS

Despite its small size, Veloce Ltd., makers of Velocette motorcycles, was known for its advanced technology.

24 “D” FOR DESMO: 1969 DUCATI 350 MK3 D

Found and bought at the 2010 Barber Vintage Festival, this Ducati has been restored to perfection.

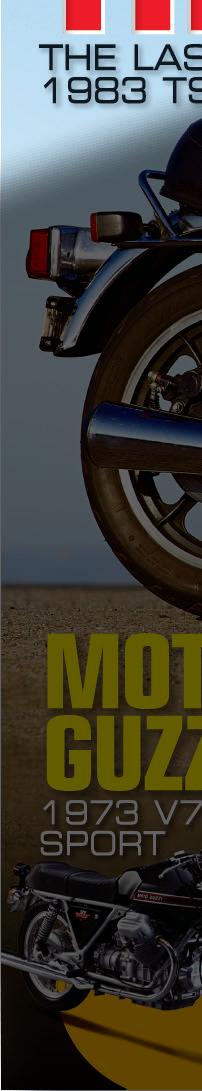

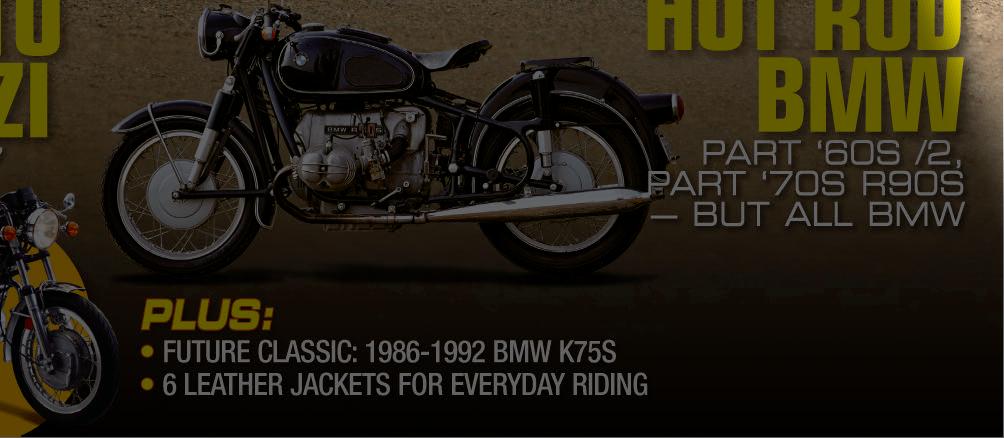

30 ELEGANCE IN MOTION: 1962 BMW R60/2

Lovingly restored and now ridden faithfully, this R60/2 hits the sweet spot.

36 1963 ROYAL ENFIELD INTERCEPTOR

The 750 Interceptor Mk1 went head-to-head in the showrooms with the new Norton Atlas 750.

42 1961 HARLEY-DAVIDSON FLH PANHEAD

In 1961, there was nothing on the market quite like the big 648-pound Harley FLH.

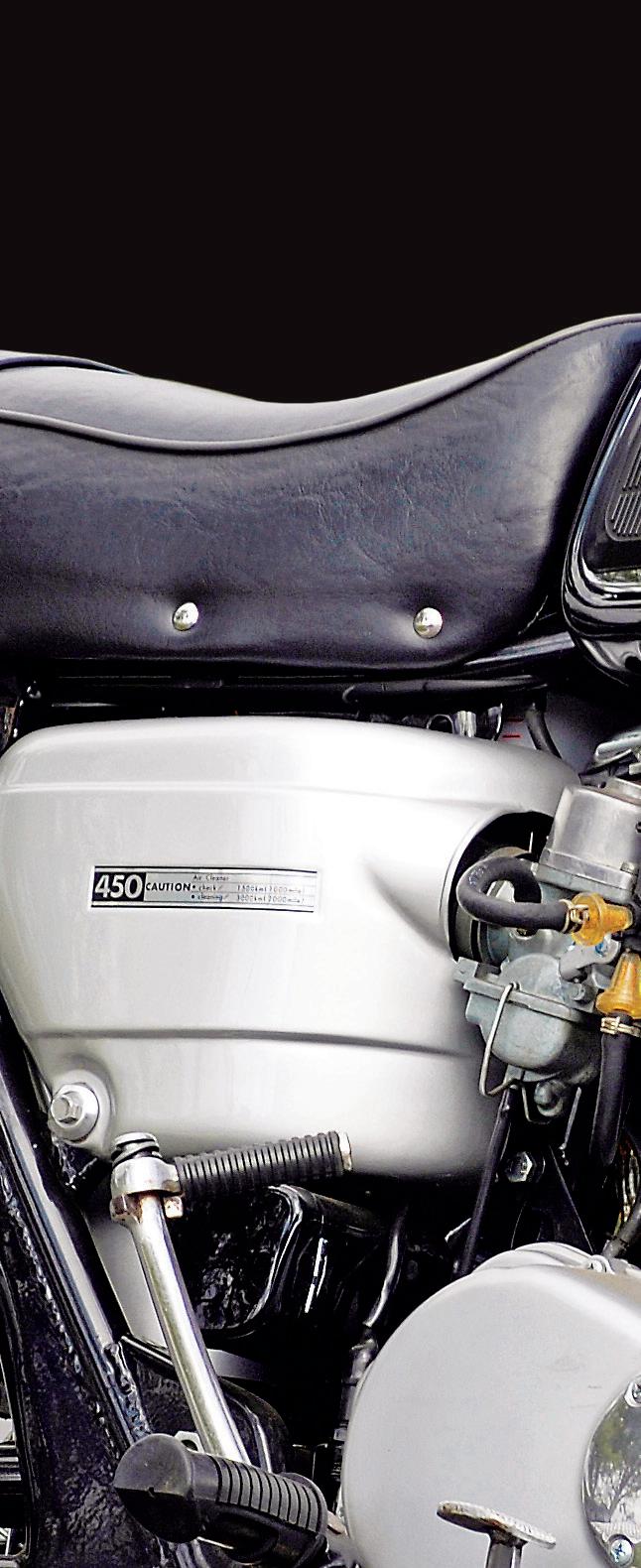

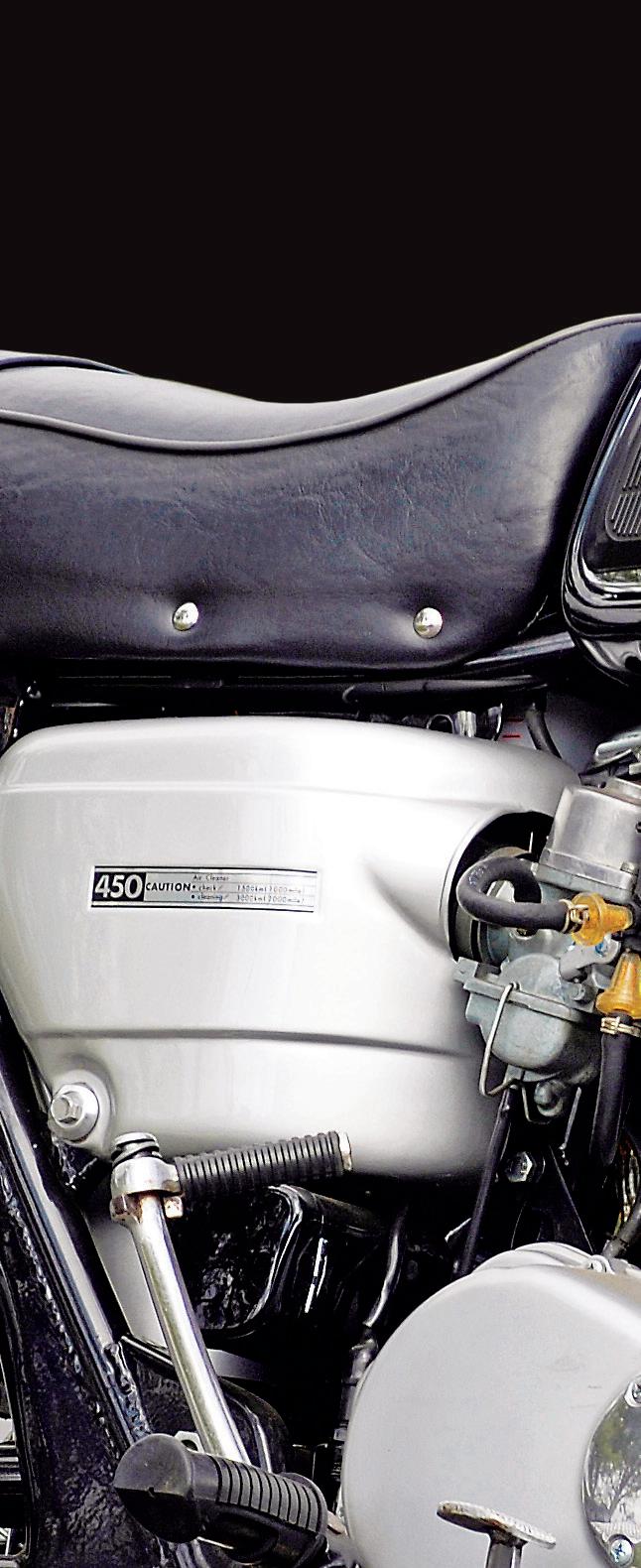

48 1966 HONDA CB450 BLACK BOMBER

Loaded with technology, the CB450 put the world on notice that Honda was playing to win.

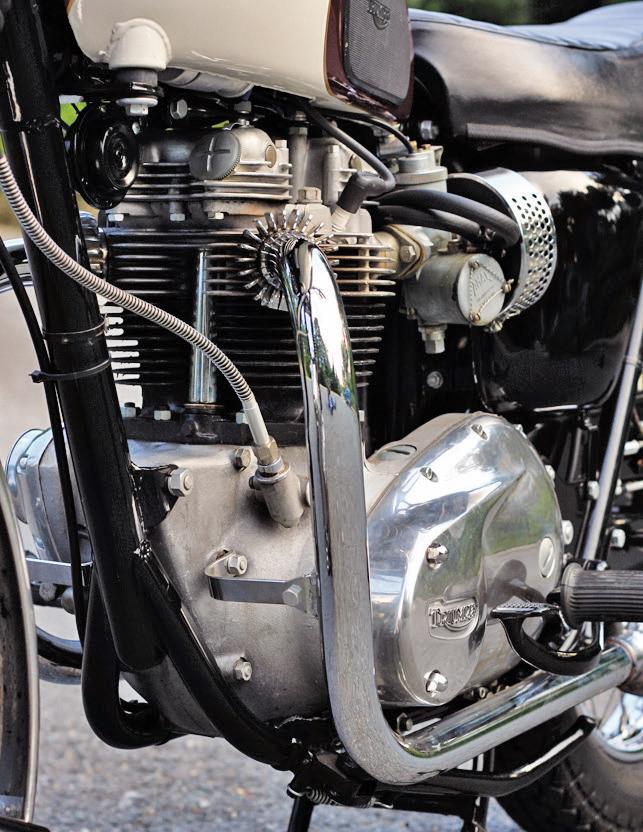

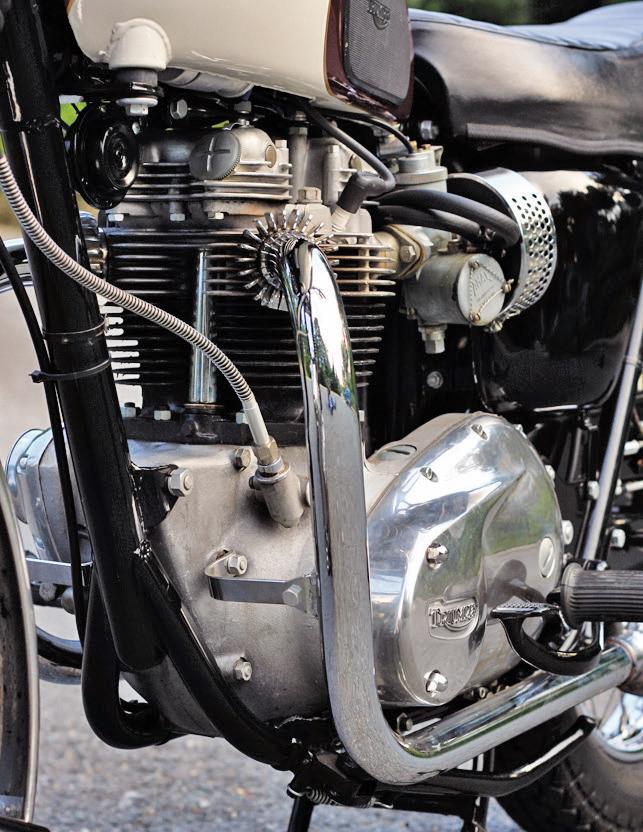

54 AMERICA’S BRIT BIKE: TRIUMPH T120

1967 was Triumph’s best year ever in the U.S., and the T120 Bonneville was its most popular model.

2 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the

NICK CEDAR

’60s

ROAD MAP 24 84

6

JEFF BARGER (2)

58 SPANISH DELIGHT: 1965 BULTACO METRALLA

Never well known in the U.S., Bultaco made trials and motocross bikes, not to mention exceptional street bikes like the Metralla.

64 1966 NORTON P11 PROTOTYPE REPLICA

It was 1966 when Bob Blair and his mechanic/parts manager Steve Zabaro worked together to blend components from two motorcycles to create the prototype of the 1967 Norton P11.

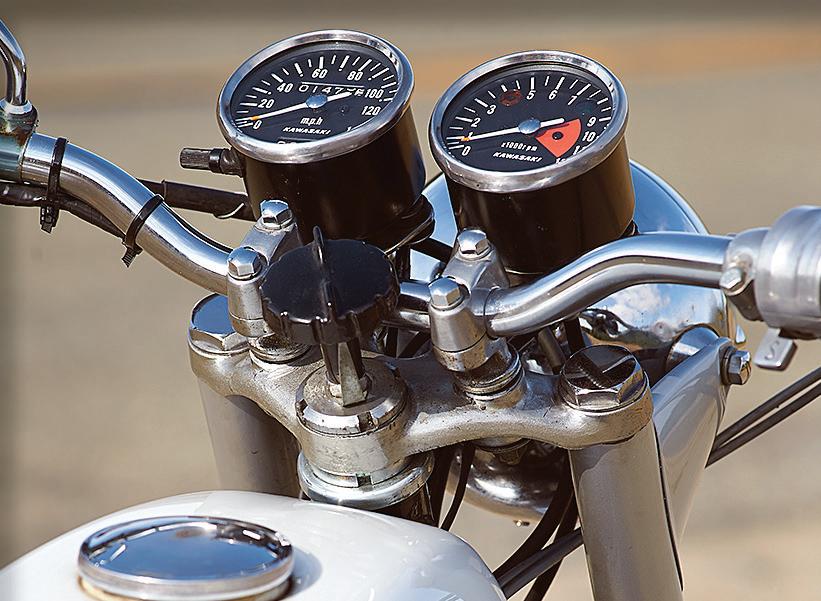

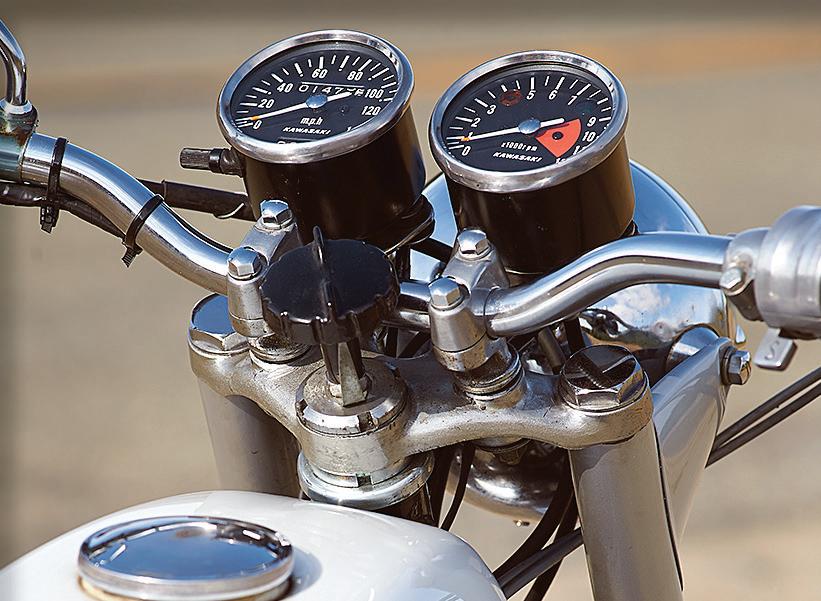

72 ON THE HUNT: 1969 KAWASAKI H1

The 1969 Kawasaki H1 was noisy, blew blue smoke and attracted troublemakers — who wouldn’t want one?

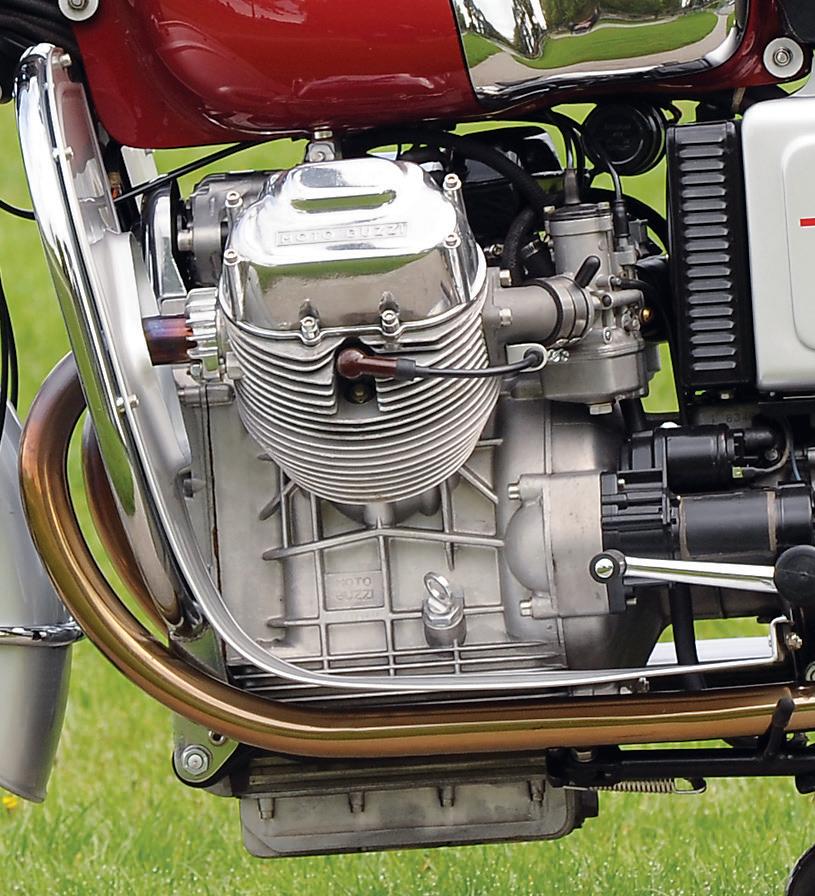

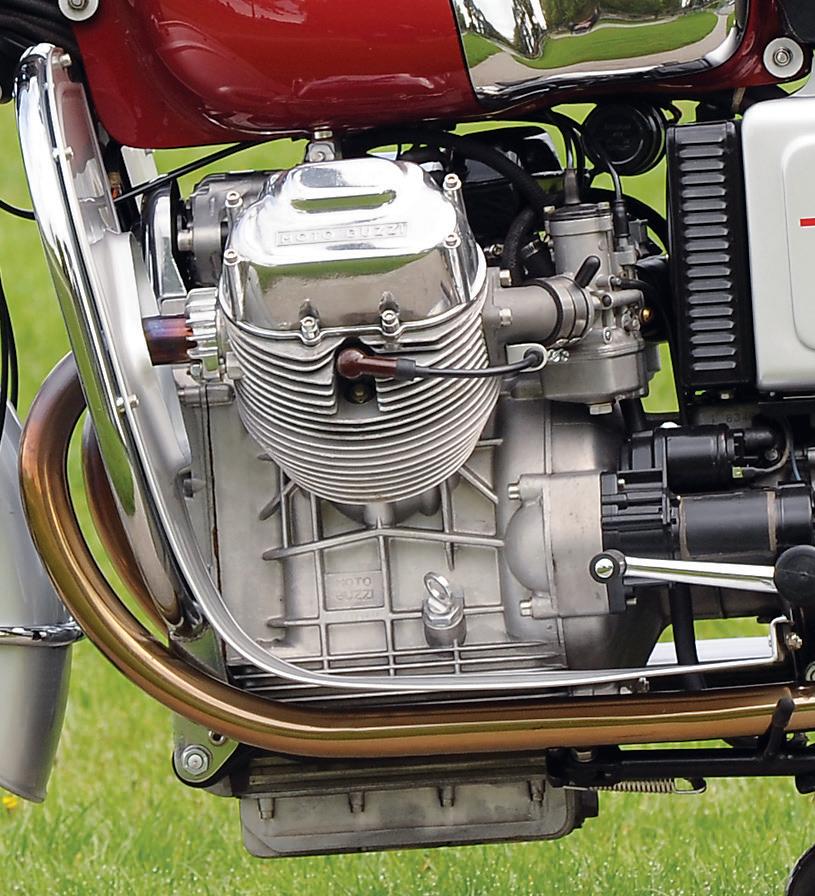

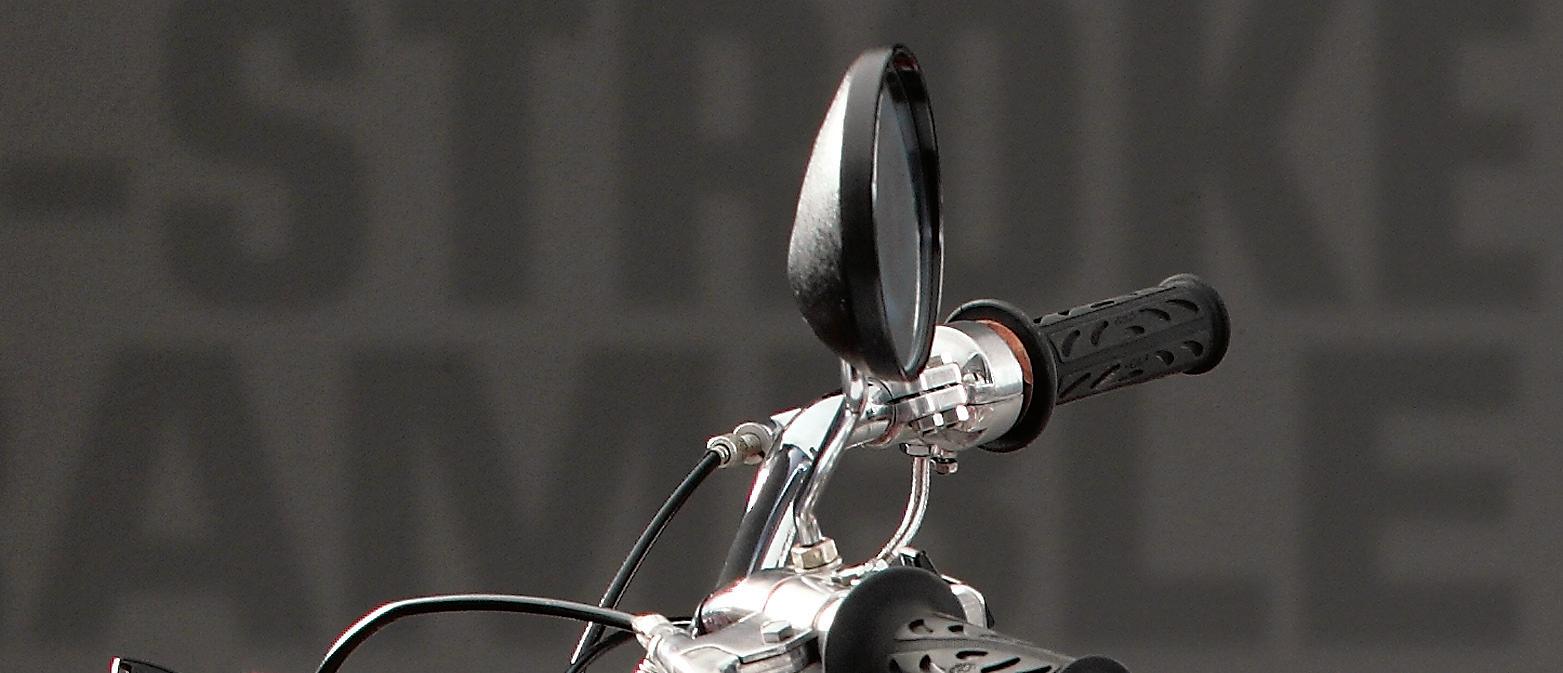

78 PAST PERFECT: MOTO GUZZI V700

In our back-to-the-future world, everything old looks new again. Moto Guzzi fan George Dockray builds a better V700.

84 TWO-STROKE SCRAMBLE: YAMAHA BIG BEAR

When Al Roller came across the 1968 Yamaha YDS-3C Big Bear in 2000, he tore it down to the frame and restored it to perfection. A few years later, it won Best Restored Japanese bike at the 2013 Motorcycle Classics Vintage Bike show at Road America.

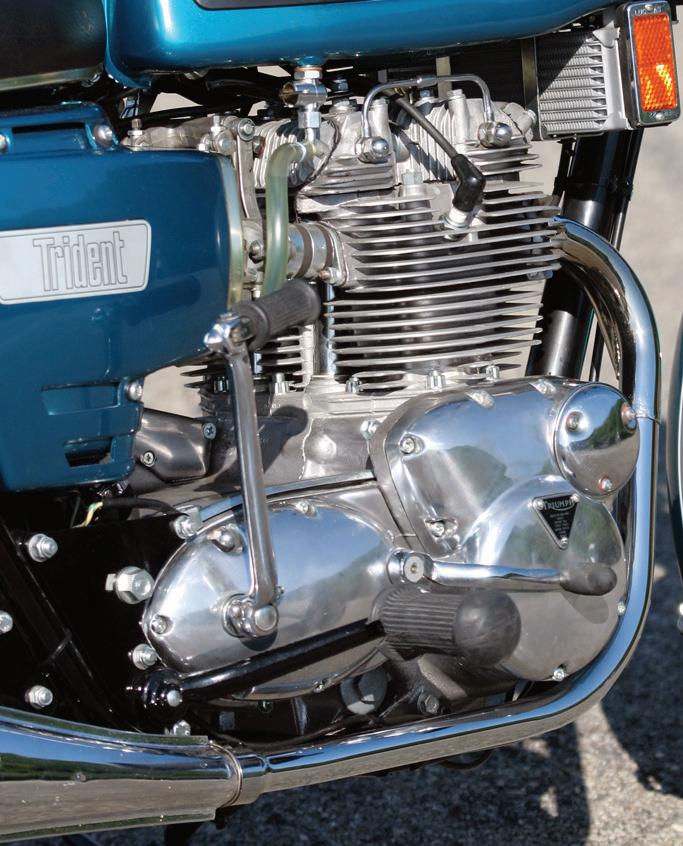

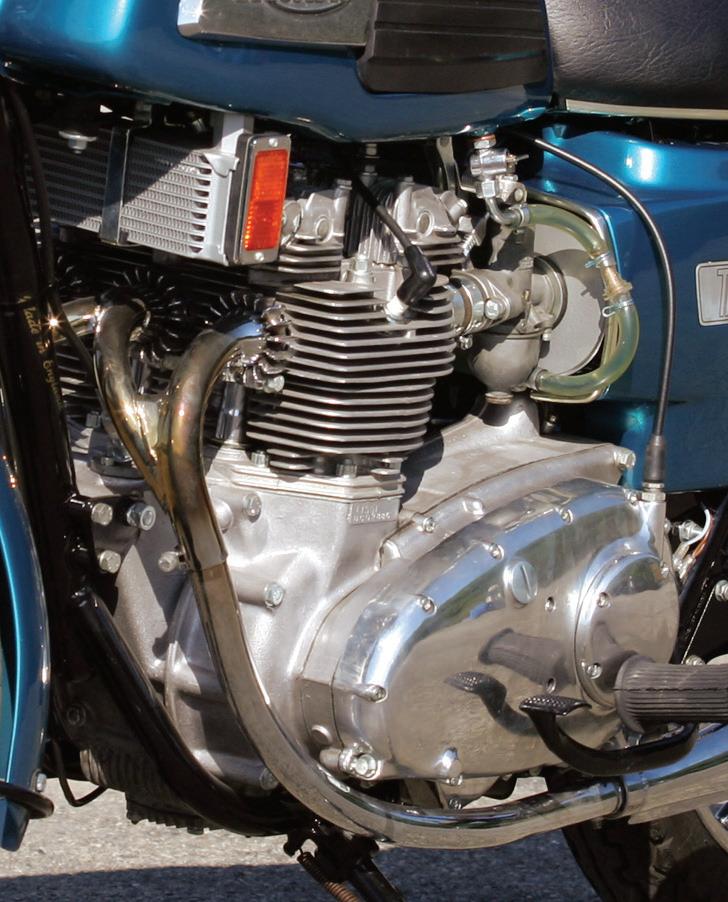

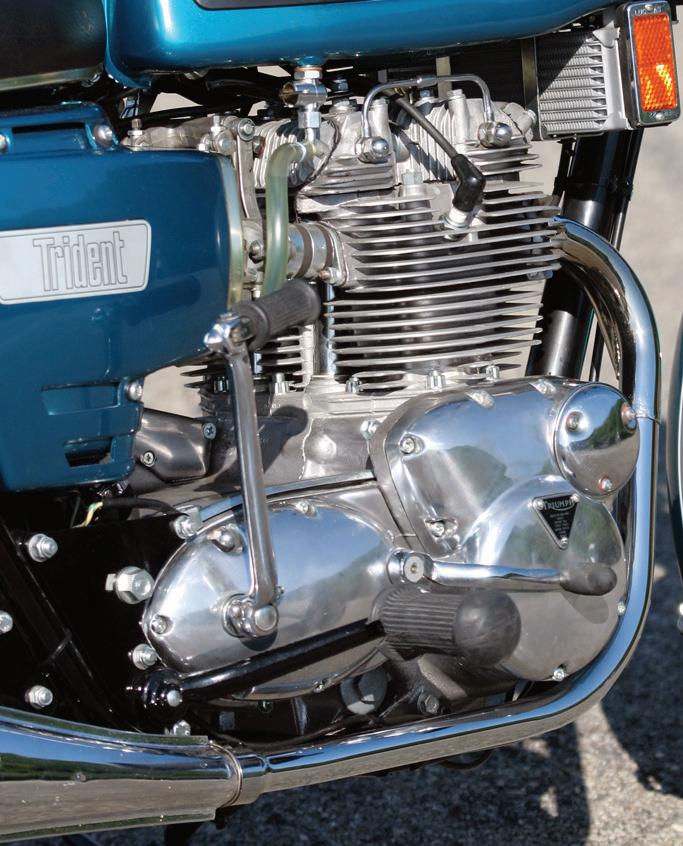

90 1968 TRIUMPH TRIDENT T150

When Triumph launched its new-for-1968 Triumph Trident T150 triple, the magazine motorheads took notice. “For you performance buffs, let us state that the Trident is the fastest street machine we have tested, bar none,” Cycle Guide enthused.

96 PARTING SHOTS: A GRAND DAY OUT ON A NORTON COMMANDO

Cam Norris awakes to a beautiful summer morning, keen to take a joyful ride aboard his classic 1969 Norton Commando S.

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 3 64 36

78

ROBERT SMITH

GARY PHELPS

JEFF BARGER

Celebrating the Sixties

World War II might be a distant memory now, but at the dawn of the 1960s the repercussions of that global conflagration were in sharp focus, present in almost every facet of modern life, whether technological or cultural, and its outcome shaped the world of motorcycles to come.

The U.S. came out of World War II the biggest winner, its war-fueled industries primed and ready for the switch to consumer-driven production. Yet it’s a curious fact that while the U.S. auto industry blossomed with fresh technology, becoming the leading global manufacturer of automobiles, the U.S. motorcycle industry did not. By 1953 Indian was dead, while Harley-Davidson was soldiering on with mostly pre-war technology, its best-selling motorcycles powered by aging flathead designs.

British manufacturers looked to the U.S., where riders seemed more interested in speed than anything else, and their light and fast machines found a ready market. In countries like Japan and Italy where the means of production had been obliterated by the war, manufacturers started with a clean sheet, targeting a new audience of post-war riders looking for cheap transportation. That decade saw a boom in manufacturing, and as the ’50s gave way to the ’60s, motorcycling became more and more about recreation and sport than efficient transportation. Foreign manufacturers — particularly in Japan — poured fresh resources of money and technology into developing new machines for a new market. Honda came to the U.S. in 1959, and in 1960, its first full year here, it sold some 2,000 motorcycles. By comparison, that same year Harley-Davidson produced fewer than 15,800 machines. Ten years later the situation was more than reversed, with Harley production essentially stagnant at around 15,500 motorcycles of all types and Honda, continuing its stratospheric rise, selling an estimated 36,000 CB750 Fours in 1969 in the U.S. alone.

RICHARD BACKUS, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF rbackus@motorcycleclassics.com

LANDON HALL, MANAGING EDITOR lhall@motorcycleclassics.com

ARTHUR HUR, ASSOCIATE EDITOR/ONLINE

CONTRIBUTORS

JEFF BARGER • NEALE BAYLY • NICK CEDAR COREY LEVENSON • SEDRICK MITCHELL

CAM NORRIS • GARY PHELPS • KEN RICHARDSON

MARGIE SIEGAL • ROBERT SMITH PHILLIP TOOTH • GREG WILLIAMS

ART DIRECTION AND PRE-PRESS

MATTHEW T. STALLBAUMER, ASST. GROUP ART DIRECTOR TERRY PRICE, PREPRESS

WEBSITE

CAITLIN WILSON, DIGITAL CONTENT MANAGER

DISPLAY ADVERTISING (800) 678-5779; adinfo@ogdenpubs.com

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING 866-848-5346; classifieds@motorcycleclassics.com

NEWSSTAND BOB CUCCINIELLO, (785) 274-4401

CUSTOMER CARE

(800) 880-7567

BILL UHLER, PUBLISHER

OSCAR H. WILL III, EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

CHERILYN OLMSTED, CIRCULATION & MARKETING DIRECTOR

BOB CUCCINIELLO, NEWSSTAND & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR

duction quickly overshadowed by Honda’s new-for-1969 CB750, the motorcycle that, more than any other, marked the beginning of the end of British

Yet even as the Japanese continued their upward march, the British held fast. The British makers weren’t pouring the same level of resources into development, but that didn’t seem to hinder their dominance in the performance category of 500cc-plus motorcycles. The big British twins were still the benchmark of performance and Triumph above all reigned supreme, selling some 28,000 machines in the U.S. in 1967, its best year ever. Recognizing the Japanese threat perhaps too late, in 1968 Triumph introduced the now legendary T140 Trident triple, an introduction quickly overshadowed by Honda’s new-for-1969 CB750, the motorcycle that, more than any other, marked the beginning of the end of British dominance of the U.S. market.

But the market was about so much more than just Honda, Harley and Triumph. Moto Guzzi and BMW, storied brands with roots to the 1920s, were developing new and more refined motorcycles, and finding growing markets in the U.S. and elsewhere. Smaller manufacturers like Bultaco flourished at the same time as some of the old guard like Velocette trembled, too small to be truly competitive and unable to change to meet the times. An era of victors and vanquished that heralded the coming changing of the guard, the ’60s brought us some of the most memorable machines of all time. We hope you enjoy this special issue of Motorcycle Classics celebrating a unique era in motorcycling’s rich history.

BMW, us some Classics motorcycling’s rich history.

Richard Backus Editor-in-chief

BOB LEGAULT, SALES DIRECTOR

CAROLYN LANG, GROUP ART DIRECTOR

ANDREW PERKINS, MERCHANDISE & EVENT DIRECTOR

KRISTIN DEAN, DIGITAL STRATEGY DIRECTOR

TIM SWIETEK, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DIRECTOR

ROSS HAMMOND, FINANCE & ACCOUNTING DIRECTOR

MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS (ISSN 1556-0880)

Ogden Publications, Inc., 1503 SW 42nd St., Topeka, KS 66609-1265

For subscription inquiries call: (800) 880-7567

Outside the U.S. and Canada: Phone (785) 274-4360 • Fax (785) 274-4305

©2017 Ogden Publications Inc.

Printed in the U.S.A.

4 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s BLACK SIDE DOWN ®

aerostich.com/motoclassics 100% Cotton Made in America FREE with your next order* *Of $27 or more. T-shirt regularly $27.

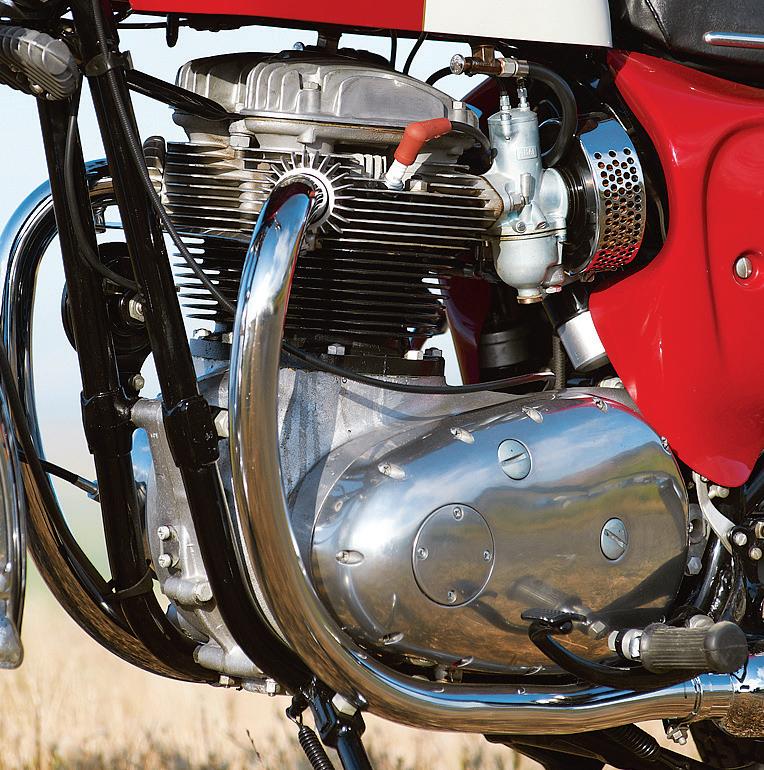

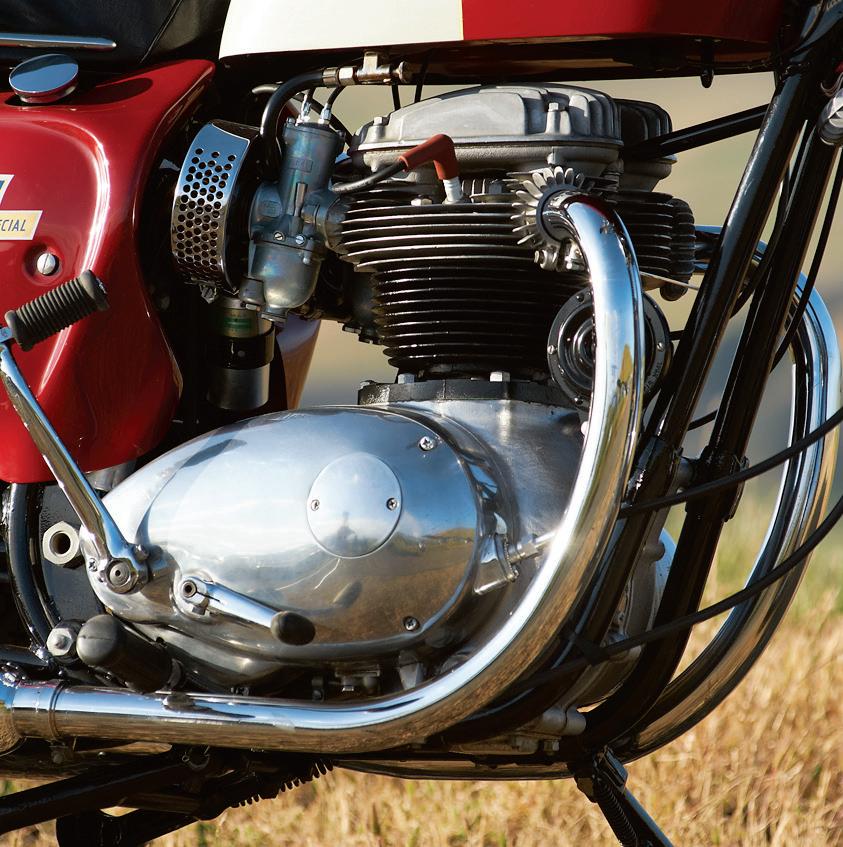

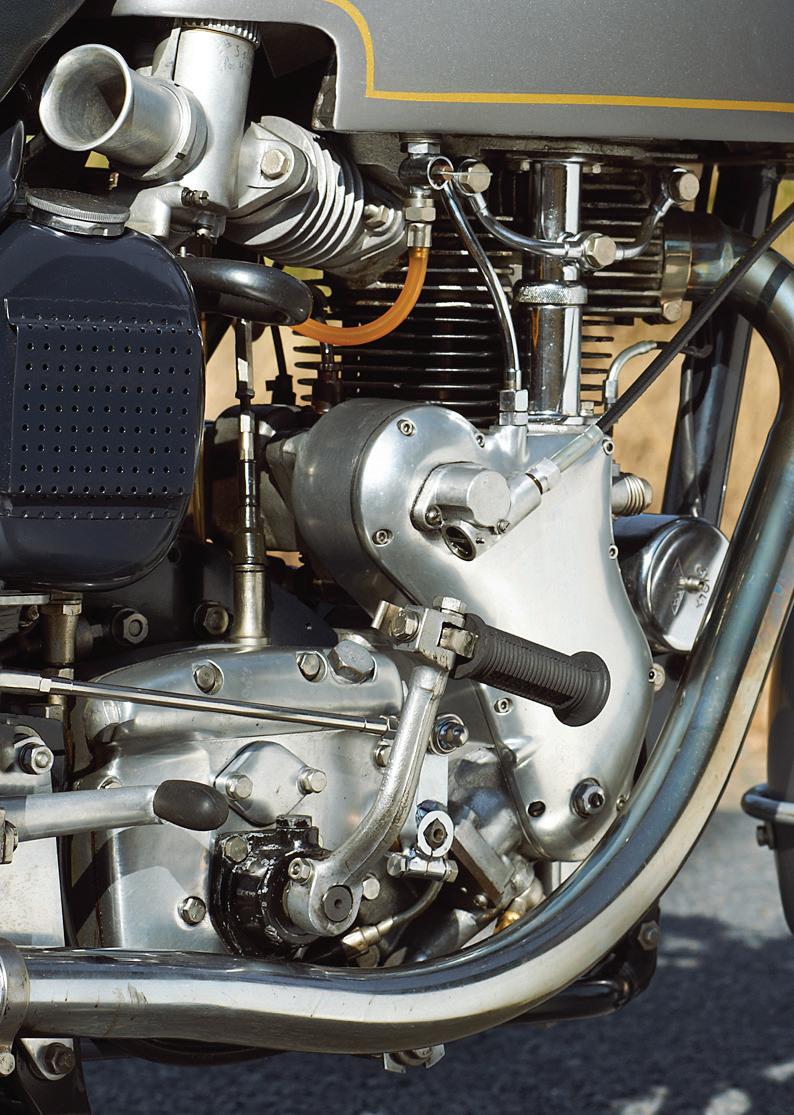

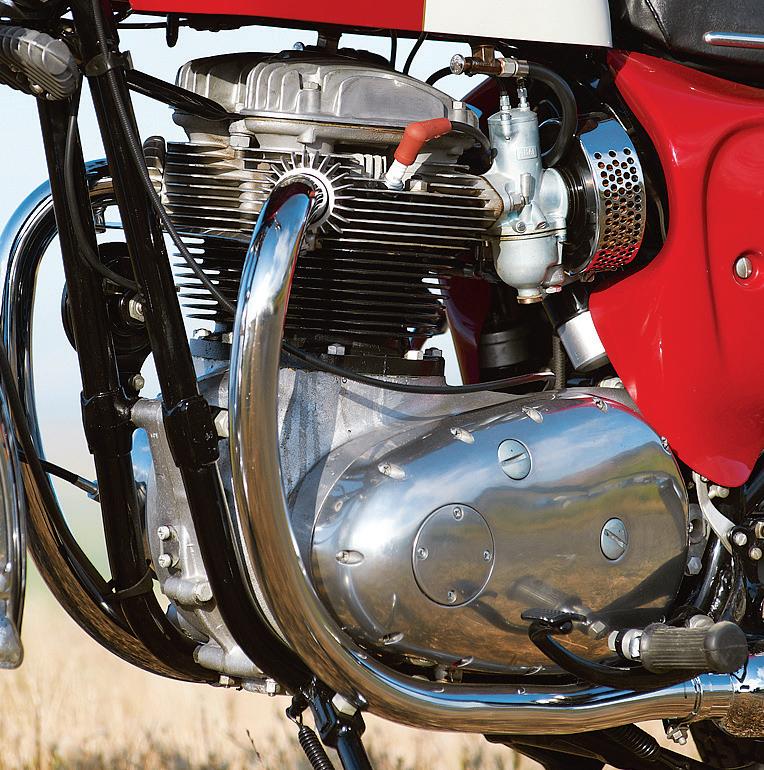

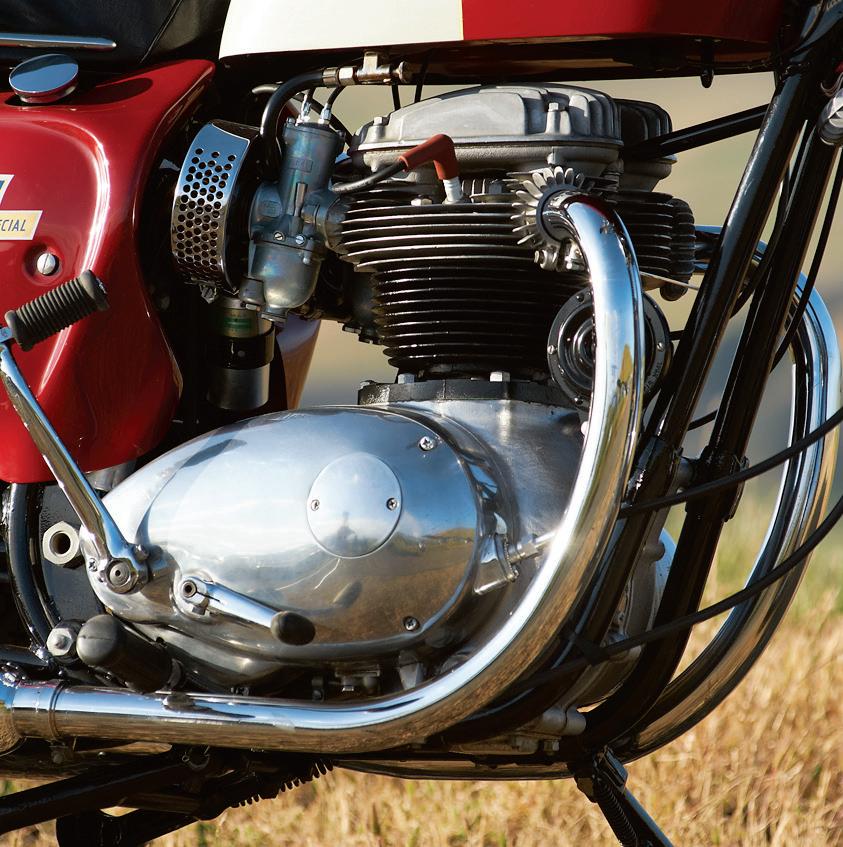

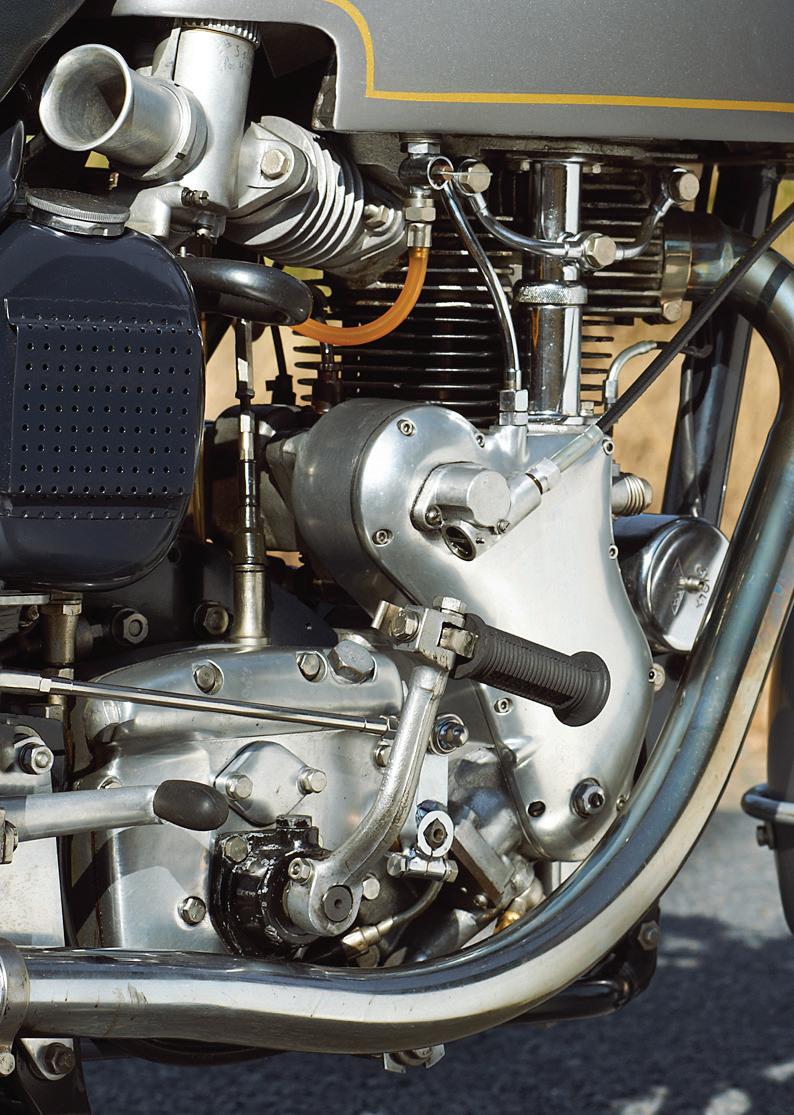

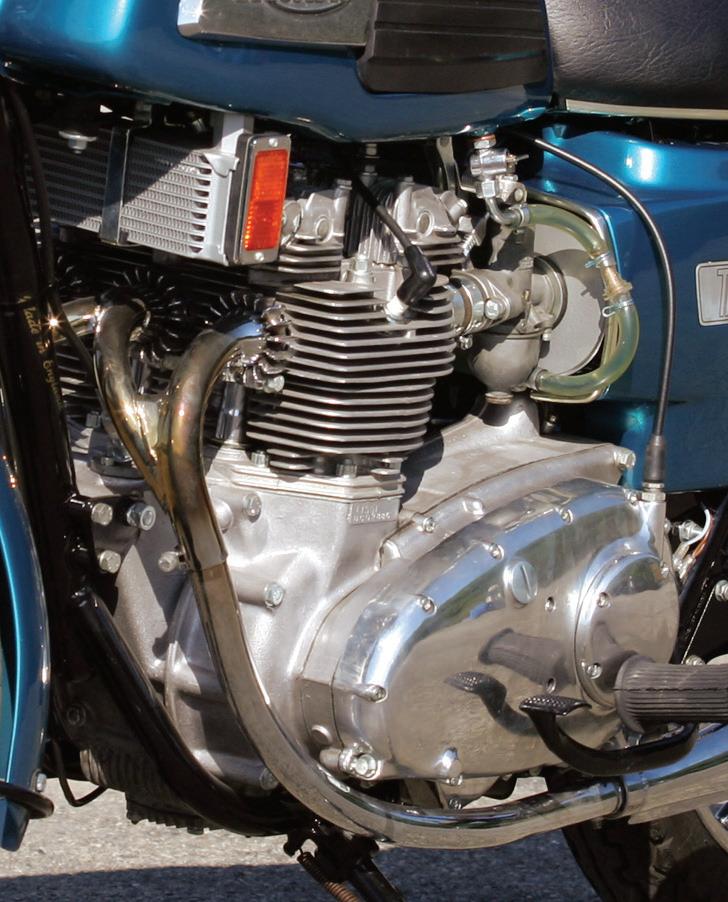

HOT ROD BSA

1967 Spitfire Mark III

Story by Margie Siegal

Photos by Nick Cedar

IIn the 1960s, BSA was known for flashy bikes with bright colors and lots of chrome. But there was more to the English import than just shine. Under all that makeup was a reliable motorcycle that handled well, ran fast and stopped when asked.

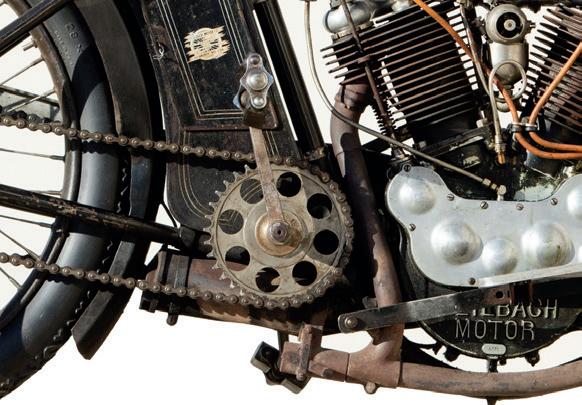

Birmingham Small Arms Company’s first motorcycles in 1903 were single-cylinder machines, with a line of V-twins following in the 1920s. The first BSA parallel twin, the A7 designed by Val Page, Herbert Perkins and David Munro in 1939, was put on hiatus when World War II started and finally appeared in 1946.

BSA weathered the war well, and by the 1950s it had the largest range of any motorcycle manufacturer in the world. Most

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 7

1967 BSA SPITFIRE MARK III

of the bikes BSA sold were the smaller, single-cylinder commuter cycles heavily in demand by British workers. And while the company had a firm policy against factory road race involvement, BSA built single-cylinder Gold Stars for clubman racers in England and flat track competition in the United States.

BSA’s better twin

By this time, BSA’s parallel twin had morphed into two versions, the 497cc A7 and the 646cc A10. In order to raise money to pay its war debt, the British government pushed English companies to export. As a result, a lot of BSA twins were sent to the United States, where the market for sport motorcycles was booming. Indian motorcycle distributor Hap Alzina was importing BSAs to the West Coast while Rich Child, the former head of Harley-Davidson’s Japanese subsidiary, was in charge of distribution east of the Mississippi. The reliability and economy

that drew British consumers did not draw U.S. riders, who were more interested in speed. American motorcyclists generally had little use for BSA’s lightweights, but were enthusiastic about BSA twins.

An obvious way to prove performance is on the race track. BSA didn’t like to sanction racing, but the company had little choice if it wanted to sell bikes in the United States. American racers found that BSA twins responded well to tuning, and with the right setup were competitive in flat track and offroad events. In 1954, BSA lent assistance to a team led by AMA National Champion Bobby Hill for that year’s Daytona beach race, and the BSA Wrecking Crew, as it became known, swept the first five places. Other National winners on BSA singles and twins included Jody Nicholas, George Everett and Dick Mann.

One of the most consistent BSA flat track stars was Al Gunter. He moved to BSA in the early Fifties and racked up seven career wins in national racing events. His home track was Ascot Park in Southern California, where he won regularly. Other BSA riding masters at Ascot were Sammy Tanner, Blackie Bruce, Jack O’Brien and Neil Keen. Together, they were known as the Ascot Wrecking Crew.

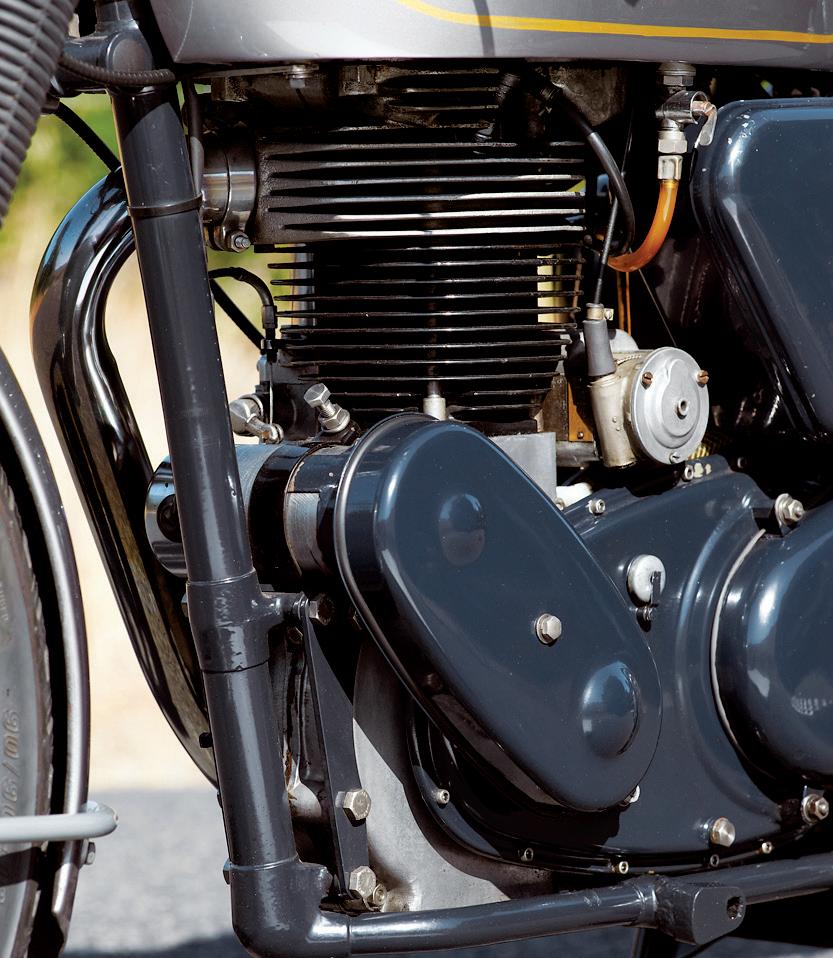

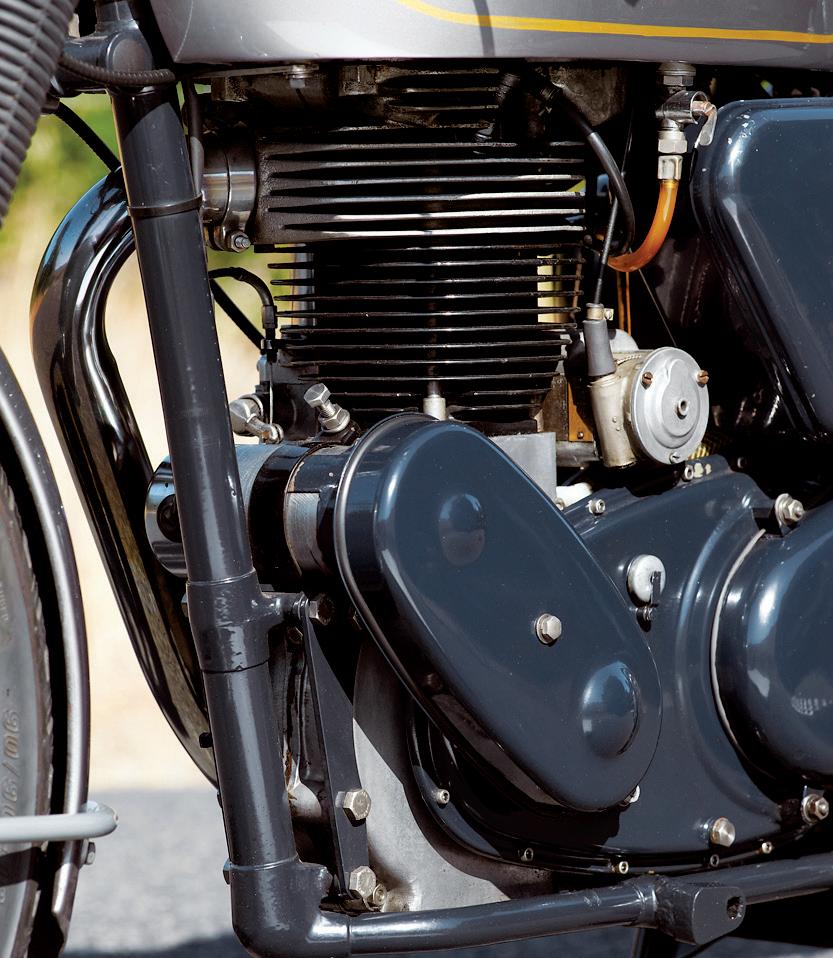

BSA continued to develop its parallel twin, and in January 1962 introduced a major revamp of both the A7 and A10 twins. The new engines were based on a common platform, with the major difference between them being the 75mm bore of the A65, which with the 74mm stroke common to both engines gave 654cc cubic capacity. The smaller A50’s bore of 65.5mm gave 499cc.

The A65 engine used vertically split aluminum alloy crankcases with a onepiece crankshaft resting on ball bearings on the drive side and a plain bushing on the timing side. The cylinder was still cast iron, while the head was aluminum alloy. Valves were operated by pushrods, and lubrication was dry sump.

The 4-speed transmission was in unit instead of a separate box bolted to

8 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s

the engine as on the A10, and an alternator handled the 6-volt electrics. Two sets of points were mounted on a single plate with an automatic advance mechanism.

The frame was similar in design to the one used on the last A10s, a dual downtube cradle with a single backbone tube under the seat. Telescopic forks in the front and Girling shocks in the rear absorbed the bumps, and the single-leading-shoe brakes were 8 inches diameter in front and 7 inches in the rear.

Going faster

In 1964, BSA started hot-rodding the A65. The Rocket A65R had the compression upped to 9.0:1 from the standard 7.5:1, with a hotter cam and siamesed exhaust pipes. British riders still wanted easy maintenance and fuel economy, but American riders wanted higher bars, smaller tanks and more horsepower, so the American importers convinced BSA to build four special U.S.-only models.

The result was the 499cc offroad competition Cyclone with no lights and open pipes, and the 654cc Thunderbolt with high bars, a small tank and the hot engine. A twin-carb version of the Thunderbolt was named the Lightning.

The last of the four U.S.-only models was the 654cc BSA Spitfire Hornet. Like the Cyclone, it was produced in response to American demand for a hot offroad/desert racer. Equipped with the twin-carb head fed by a pair of 1-1/8-inch Amal Monobloc carburetors and available with either 9:1 or 10.5:1 compression, it had a 2-gallon fiberglass gas tank, a high performance cam and straight-through pipes.

In line with BSA’s East/West Coast distributorships were separate East Coast and West Coast models. The East Coast version had high pipes and the West Coast model had low

pipes. If riders wanted to hit the street, BSA’s ET (energy transfer) ignition system could be easily adapted to add lights.

By this time, BSA was experiencing cracks in the corporate wall. Better wages for English workers meant many of BSA’s get-to-work customers were buying inexpensive automobiles coming on the market, and Japanese motorcycles were being imported to England and America in record numbers.

Making matters worse, the British manufacturers weren’t reinvesting their profits into developing their products. In the 1960s, BSA was building motorcycles on machine tooling from before World War II. The Japanese manufacturers, however, were making major investments in tooling and design, enabling them to offer oil-tight cases, overhead cams and electric starting at prices competitive to the much more primitive English machinery. Certainly the Brit bikes handled better, but that was a priority for a minority.

BSA management, who had continued to believe that its customers were forever loyal, was discovering that the get-to-work rider who didn’t buy a car was likely to buy a Honda over a BSA.

New bikes

The company tried to cope by fielding state of the art advertising campaigns and building stylish motorcycles targeted to the sport rider. For 1965, BSA dropped the single carburetor A65R for the American market. There were now 11 versions of the twin, but the 499cc versions had to compete against the new Honda CB450, which had double overhead camshafts, constant velocity carburetors, electric start and a twin-leadingshoe front brake.

For 1966, there were only six versions of the twin, two 499cc models and four 654cc. To counter problems with the drive-

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 9

“The British manufacturers weren’t reinvesting their profits into developing their products.”

side ball main bearing, it was changed to a lipped roller race. This turned out to be a bad move, as at high speeds the crankshaft could pull to one side and occasionally cut off the oil supply, resulting in a rod through the cases. Although BSA never acknowledged the problem, ingenious privateer mechanics developed a more reliable bearing.

The intake valves were enlarged, the transmission was improved, a timing notch was added to the flywheel and a balance pipe was added to twin carb models. The frame was revised, and twoway damping was added to the forks. A 12-volt system replaced the now outmoded 6-volt lights.

The BSA Spitfire was introduced, replacing the limited production Lightning Clubman. Amal GP 1-5/32-inch carburetors replaced Monoblocs and the 190mm front brake from the defunct Gold Star was standard. The Hornet (with the Spitfire half of the name dropped) continued in production as a desert racer. Actor Steve

McQueen, a dedicated offroad competitor, tested the Hornet in 1966 and wrote up the test himself for Popular Science. He praised the BSA’s powerful engine and the excellent air cleaner, but downgraded the machine for excess weight.

“The Hornet also had a tendency to want to go its own way. I always had to stay on top of it. But it sure had a good-functioning powertrain,” McQueen said. “I also think the front forks should be raked on a more forward angle. With this adjustment, the BSA would have a more stable ride in the rough and would be generally a smoother performer.”

Cycle World tested a Mark II Spitfire on the drag strip and notched quarter mile results of 14.9 seconds, with a terminal velocity of 89mph. Unfortunately, the once-excellent BSA quality control was becoming spotty, and a run of defective ignition points cams resulted in overheating and bad performance.

The problem was corrected the next year with the Spitfire Mark III. New for 1967 was a new rocker box cover with fins and an inspection hole (with cover) for checking ignition timing with a strobe. Compression was reduced a little to 10:1 from 10.5:1, and the GP Amals were swapped for easier to tune (and cheaper) 932 Amal Concentrics. The dual seat grew a hump in the rear, and the tires were mounted on aluminum Borrani rims.

The Spitfire was continued for another year (as the Mark IV) before it was dropped to make room for the Rocket 3 triple. BSA managed to keep going until 1972, when mismanagement, an aging product line and competition from Japanese motorcycle manufacturers drove the company into bankruptcy.

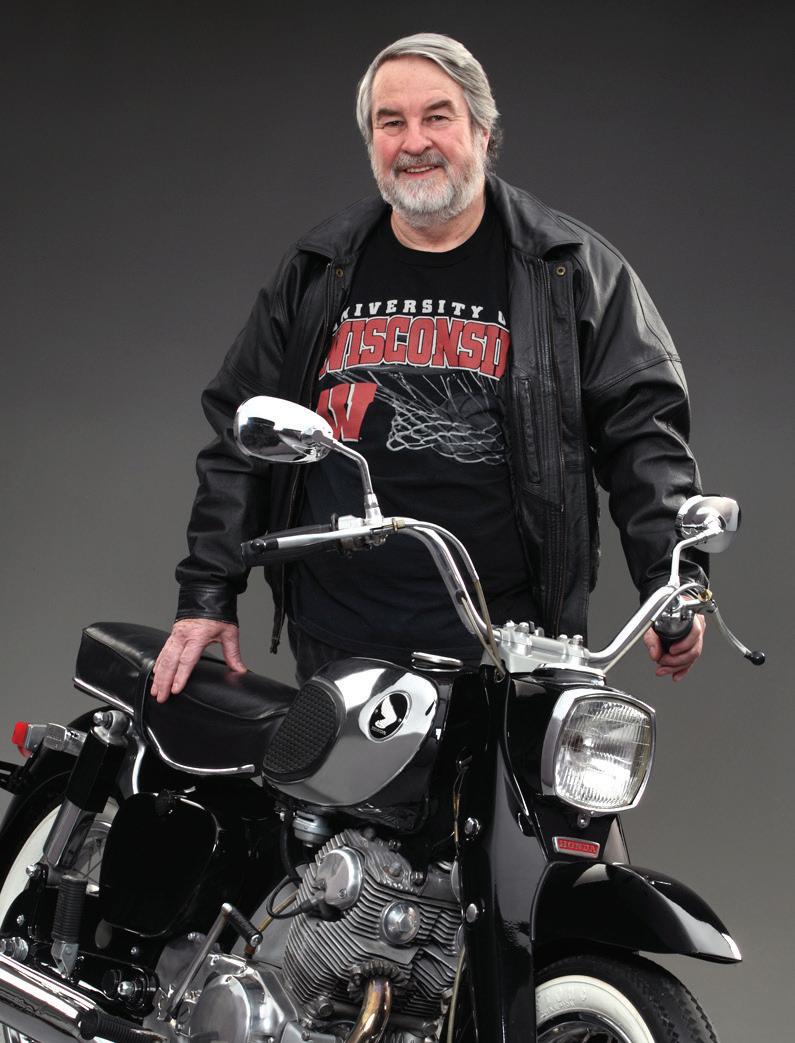

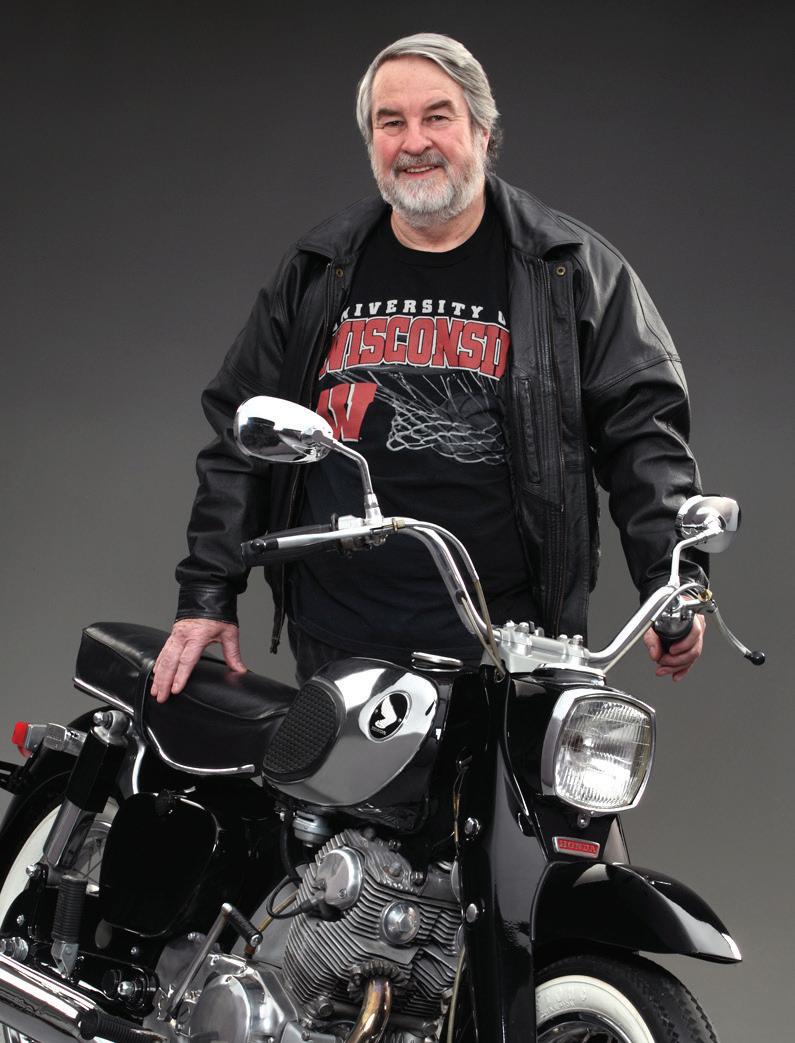

Don’s Spitfire

Don Johnson is a little too young to remember the glory days of BSA flat track racing, but he likes BSA sporting motorcycles. “There’s a visceral quality to Brit bikes as opposed to the industrial quality of Japanese motorcycles,” he says.

Don is a collector who rides his bikes. When he happened across this Spitfire, he found it interesting and bought it. It was all there and only “slightly restored,” Don says. “I ripped it apart, examined everything and put it back together. It was all original and within spec.”

All sorts of things can go wrong during the restoration of a 40-year-old motorcycle, but Don lucked out. Pretty majorly, actually, as the issues

10 Motorcycle classics Street Bikes of the ’60s

“The GP Amals were swapped for easier to tune (and cheaper) 932 Amal Concentrics.”

The

dual seat grew a hump in the rear for 1967. The single-leadingshoe 7.5-inch front drum brake was good for its day.

The gas tank is a new-old-stock fiberglass tank that’s been lined with epoxy.

that arose were limited to three items: sticking carburetor slides, a crumbling wiring harness and a leaky fiberglass gas tank. The popularity of old British motorcycles has given a boost to cottage industries that manufacture most parts, often with better quality control than the originals, and you can still buy new Amal carburetors and parts for most Amal models produced since World War II.

A new wiring harness was easy to find, and Don says that most of the criticism aimed at Lucas “Prince of Darkness” electrical parts should actually be directed at the wiring harness. “Some stuff was not up to the task, but most Lucas components are reliable if you keep them clean and adjusted,” Don says. “Most parts got no attention until they quit. But Lucas does have one advantage — you can fix most things at the side of the road.”

The part that was hardest to repair was the gas tank. Old fiberglass tanks tend to weep and seep. As purchased, the Spitfire had a metal BSA Lightning gas tank bolted on, with the correct fiberglass tank in a box. Don discovered a new-old-

stock tank in the shop of an acquaintance, and decided to buy it and use it instead of the compromised original.

Modern gas is hard on old fiberglass tanks, and a partial remedy is to carefully coat the inside with clear epoxy sealer from outfits like Caswell. But as experienced users will tell you, coating the inside of a tank is an art. Don pours in the compound and waits until it looks like it is starting to harden, then turns the tank so that the excess epoxy settles where he thinks the leak is. Since the filler neck is proud of the tank, getting excess epoxy out is very difficult, so Don just turns the tank so the last few spoonfuls settle at the bottom.

Don says that properly tuned and prepped, the Spitfire isn’t too hard to kickstart. “It was the hot rod of BSA’s line of twins after they discontinued the Rocket Gold Star,” Don says. “It’s as fast as a Triumph if it’s tuned right, and it stops a lot better than Triumphs of the era. Nowadays, I just like to putt along and enjoy the scenery. It handles very nicely for what I like to do. The lights are adequate, and the suspension is not bad. If you do it up right the Spitfire is reliable. It sure is eye-catching. It’s so red.” MC

“It’s as fast as a Triumph if it’s tuned right, and it stops a lot better than Triumphs of the era ... It sure is eye-catching. It’s so red.”

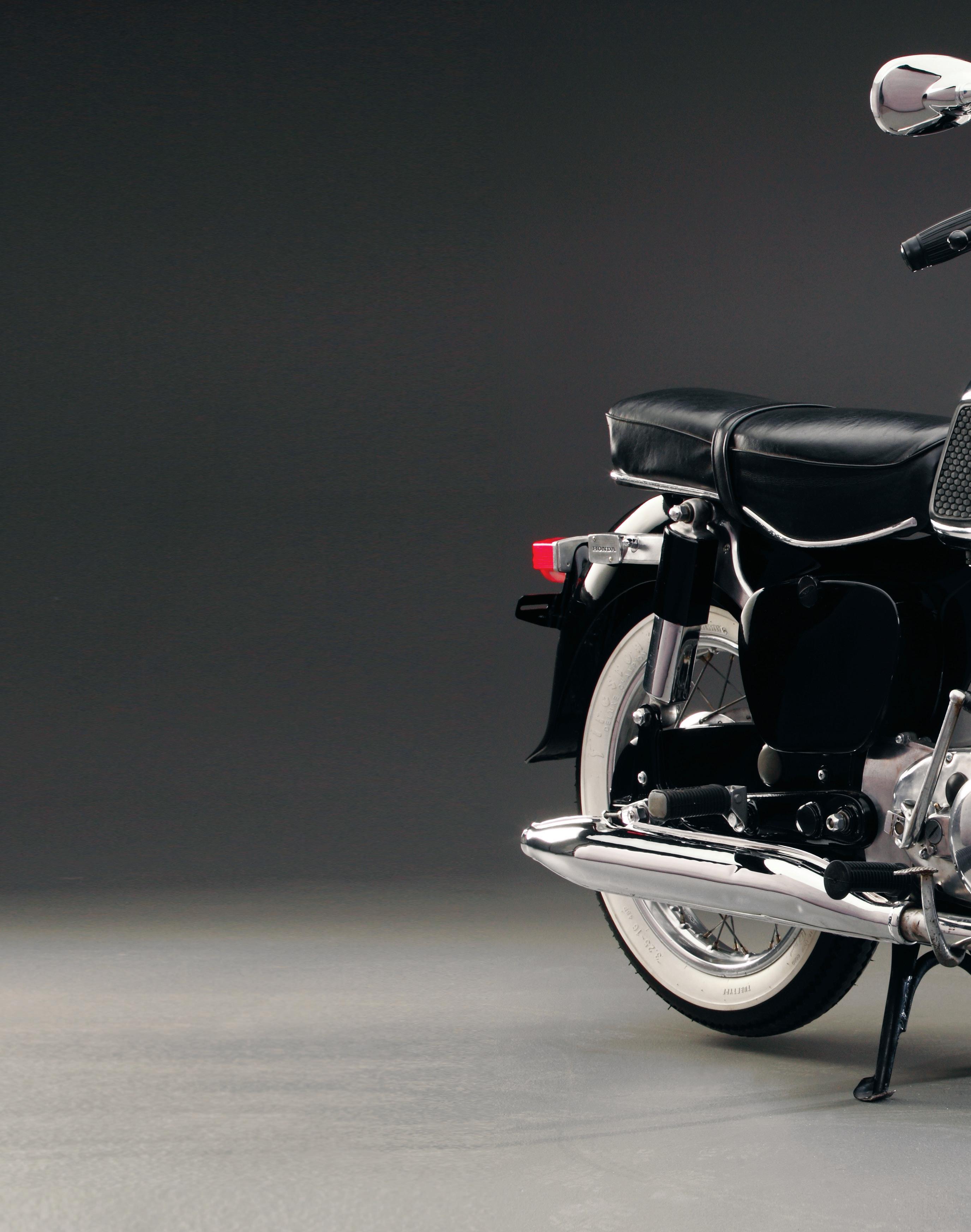

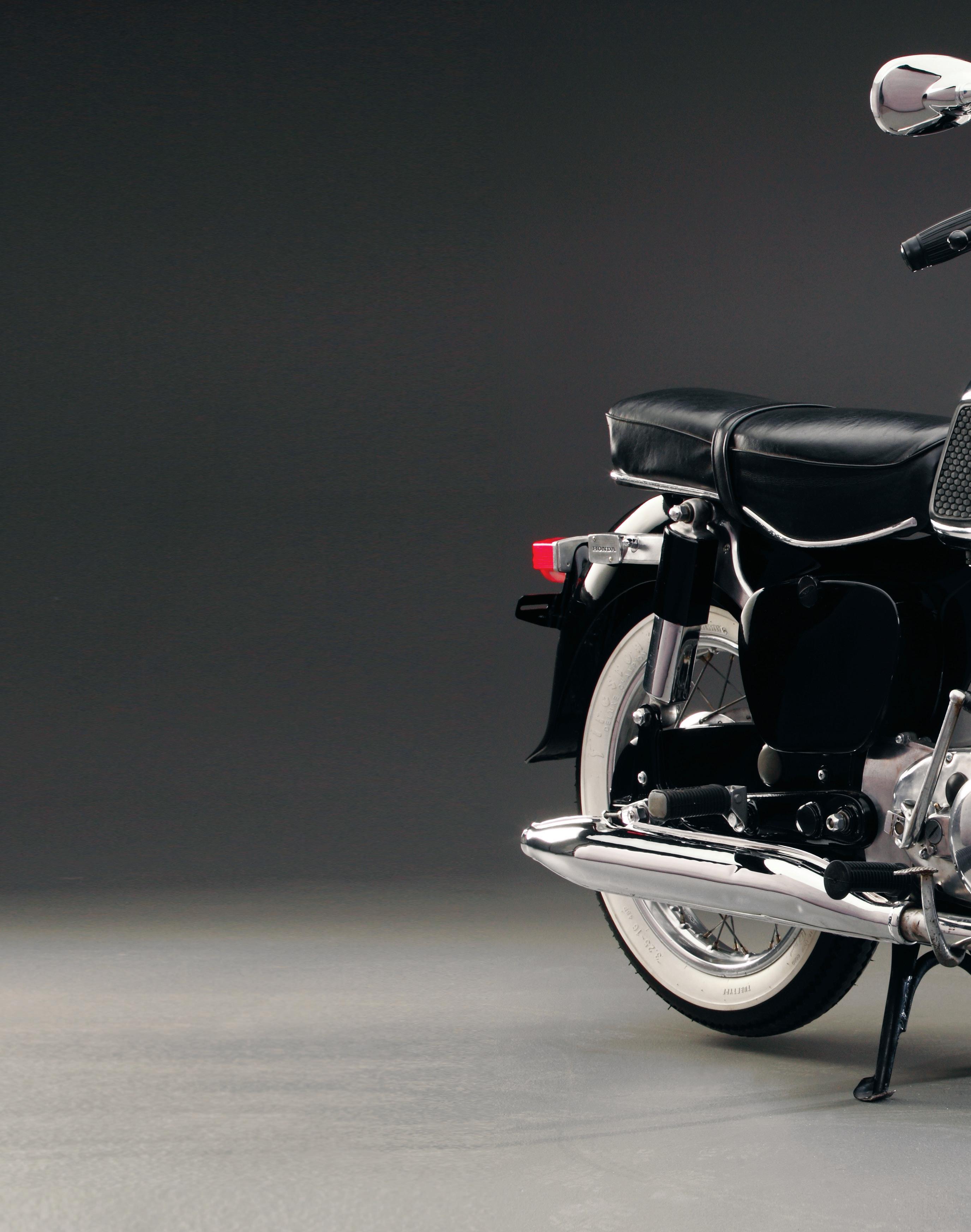

DREAM MACHINE

1966 Honda CA77 Dream

AAll dressed up in angular sheet metal, the Honda Dream is instantly recognizable as a machine of the 1960s. Those sartorial straight lines and sharp creases of the Dream are also instantly polarizing — eliciting a love-it-or-loathe-it kind of reaction.

Regardless of how you feel about the blocky and chunky machine, for many who came of age in the era of the Dream the model brings back happy memories. Take Jim Jebavy of New Berlin, Wis. In 1966, he was a high school senior in the town of Two Rivers on Lake Michigan, and several of his friends had motorcycles. Many owned Dreams, and Jim remembers cadging rides aboard the 305cc Hondas. At the time he had never owned a motorcycle, having instead invested in a car. Come winter, he was the popular man with his friends.

Several decades later, Jim found himself reflecting on his high school days. Funny thing was, it wasn’t the car he remembered, but the Honda Dreams he’d borrowed and taken for rides. “Back then the Dream looked kind of strange — it had a unique and unusual shape,” Jim says. “But the bikes were very well put together, and they were also very simple to operate.”

Simple by design

Jim’s impression of the Dream is exactly the kind Soichrio Honda hoped to make with his products. From the first motorcycle Honda built, the designer believed that small displacement multi-cylinder engines were superior to large, thumping singles. And in 1957, Honda wasn’t beyond riffing on a concept that worked when the fledgling motorcycle maker introduced its C70 Dream.

The engine found in NSU’s Rennmax, with its twin forward-canted cylinders and gear-drive double overhead cam, inspired the 247cc 4-stroke twin powering Honda’s C70. Unlike the Rennmax, Honda’s C70 featured a chain-drive single overhead cam, but otherwise featured horizontally split crankcases with a pressed-together ball bearing crankshaft and dry sump lubrication system. After the C70, Honda developed the 247cc C71, which featured an electric starter. Bumped up to 305cc, the same engine was introduced to North America in the CA76 Dream in 1959. There were, in fact, several different versions of the 247cc and 305cc Dreams imported that year, but none in very great numbers.

The dry sump CA76 lasted a single year, replaced in 1960 with the CA77 Dream Tourer. Honda updated the CA77 with a wet sump engine and also offered a 247cc CA72. Both the 247cc and 305cc Dreams used a 360-degree crankshaft, meaning the twin pistons rise and fall

Story by Greg Williams

Photos by Jeff Barger

12 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s

simultaneously, but fire alternately. Fuel and air mixed in a single 22mm Keihin carburetor, and exhaust left the robust cylinder head via dual-wall header pipes before exiting through mufflers equipped with removable baffles. The 305cc twin was rated at 24 horsepower at 8,000rpm.

Early vs. late

Dreams produced from 1960 to 1963 are called “early” models, while machines built from 1963 to 1969 are dubbed “late” models. Differences between early and late are few. Visually, the shape of the gas tank changed, but the rectangular rear shock absorber upper covers and the square headlight nacelle, complete with speedometer, remained. Over its production run, Dream specifications continued virtually unchanged.

Honda built a surprising number of offshoot models based on the Dream, including the CSA77 Dream Sport; a 305cc Dream equipped with a high-level exhaust system to distinguish it from the Tourer.

Honda used metal stampings welded together to make the frame, which included the headstock and the rear fender. There was no front downtube; the engine bolts in at the cylinder head top cover and at two points directly behind the rear case, thus acting as a stressed member. A leading-link front fork (also made of pressed steel), while not known to provide razor-sharp handling, provided effective suspension.

Front and rear wheels were a stubby 16 inches each, and most Dreams came equipped with whitewall tires. Unlike the small C100 Cubs, which featured some plastic bodywork, the Dream is all steel, even the deeply valanced front fender and side covers. Dreams were available in white, black, blue and scarlet red.

We’d be remiss not to mention Honda’s sporting CB72 Hawk and CB77 Super Hawk, which used engines based on the Dream powerplant. However, the CB-series engines were modified with a 180-degree crank, and in the case of the 305, made 28 horsepower. Hawks and Super Hawks gave up the pressed steel frame, using a more traditional tubular steel chassis and hydraulic front forks.

Finding a Dream

Jim’s nostalgia for a classic Dream led him to the computer and the Internet, but his research quickly turned to an active search when he decided it was time to buy. He monitored Craigslist and eBay and placed bids on a few local Dreams, but wasn’t successful until late 2010 when he finally landed one in Sheboygan, Wis. It was more than one Dream — for $900 Jim got a package deal including a 1966 CA77 Dream, plus a parts bike of the same year.

Both were in rough shape, but the engines turned freely in both bikes. The better of the two Dreams was covered in mud and had been ridden offroad as a trail bike before being improperly stored. Prior to disassembling the main Dream,

14 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s

1966 HONDA CA77 DREAM

Jim took time to ensure the engine would run.

“I just wanted to make sure I had a viable engine. So I rebuilt the carburetor, put in new plugs, changed the oil, cleaned the points, put a battery in it and messed around with the wiring,” Jim says. “With some fresh gas the engine fired right up, but it ran rough. I shut it down right after that.”

Working in his cramped garage, Jim completely disassembled the Dream and then carried the various subassemblies to the basement. He says his wife, Ida, thought he was nuts but patiently encouraged the work. Cleaning as he went, Jim made a list of items he thought he’d need. Admitting his frugality, he was

determined to use as many original pieces as possible from both the main Dream and the donor bike.

First was the engine. “The guy I bought the Dreams from had given me the name and number of a one-man shop,” Jim says. “He only works on one bike at a time, and because I’m not an engine guy, I called and asked if he could rebuild my engine.”

Murre’s Salvage Yard is just north of Milwaukee, and owner Dave Murre told Jim he could look at the 305 just after Christmas. So Jim continued cleaning parts and sandblasted the sheet metal before taking it to Leroy Gerber, a panel beater and painter in Oak Creek, Wis. Using a hammer and dolly, Leroy removed

Aside from the levers, perches and mirrors, Jim Jebavy’s Dream is remarkably correct. Jim tried to use as many original pieces as possible.

every dent and even reshaped the unique flare at the bottom of the front fender. “I always thought the flare looked a bit goofy,” Jim says of his early impression of the Dream. “But I like it now. Those fender flares are always damaged. They get smashed up the minute someone rides over a curb.” The Dream has a two-piece enclosed sheet metal chain guard, and Jim’s donor bike yielded a bottom half in good condition to go with the main bike’s upper piece. Leroy primed and painted all of the metal gloss black.

While Jim waited for Dave to accept the engine, he went through the wiring harness. His original Dream’s harness was “a bastardized mess,” but the donor bike had one in reasonable condition. He cleaned the wires and their ends, adding heat shrink tubing in some spots as deemed necessary, and replaced a couple of damaged connectors with those removed from the other harness.

Working with S.O.S cleaning pads, Jim cleaned every piece of chrome. “I was looking for a rider and not a show piece,” Jim says of his restoration philosophy. His cleaning went right down to the wheels: Removing two spokes at a time, Jim took the time to clean them up, buff the rim and hub, and reinstall them, working his way around each wheel. “The bike does show its age in places,

but I got everything as good as I could,” he adds. Jim didn’t have to source replacement wheel bearings or brake shoes, as the originals were usable.

The donor bike’s handlebar was in better shape than the main bike’s, so it was cleaned and detailed for use. Without a decent set of levers and perches Jim ordered aftermarket parts from JC Whitney. But those perches, with larger threaded holes for mirrors, meant he couldn’t install the correct rectangular-shaped Honda mirrors. Instead, he ordered a set from JC Whitney.

Jim bought a replica seat cover and slipped it over the original springs and foam, and found a replacement chrome trim strip on eBay. “This project was made so much easier thanks to the computer and the Internet,” Jim says. “You can find parts and pieces, you can log on to a forum like honda305.com and ask a question and almost always get an answer — I don’t think I could have done it without the computer.”

Together again

Jim delivered his main Dream engine, together with the donor unit, to Dave early in 2011. Dave took both engines completely to pieces and found that the main Dream engine, apart from a worn transmission shaft, was in reasonably good condition — the donor engine yielded up a clean shaft. Bearings and seals were replaced in the bottom end, and the cylinders were treated to a fresh bore and new 0.010-inch oversized pistons and rings before being buttoned back together. Jim brought the finished pieces out from the basement to the garage and assembled them into a rolling chassis. When the engine came back, it slipped easily into the frame.

Jim finally poured gas in the tank and fired up the Dream in the fall of 2011, but it was running rough. Snow came before he could fine-tune the Dream, but early in 2012 he took the bike to The Shop in Milwaukee, where the timing was found to be out 180 degrees. Once corrected, the Dream fired and purred like a sewing machine. Jim originally had a set of ill-fitting mufflers he bought on eBay, but he bought another CA77 project with a set of original mufflers. He had these cleaned and chromed, and installed the proper baffles.

“I’ve put on probably 600 or 700 miles, and it’s great to ride to the hardware store or over to a friend’s house. It’ll do 50-55mph, and it’s great on the slower roads, but I wouldn’t want to take it out on the freeway,” Jim says. Of photographer Jeff Barger stopping him at the Rockerbox Motofest in Milwaukee and asking about the Dream, Jim says, “This is my Oscar moment — I’m thrilled that I did the work and that someone else appreciates the irregular styling of the Dream.” MC

16 Motorcycle classics Street Bikes of the

’60s

The overhead cam 305cc twin produces 23 horsepower at 7,500rpm.

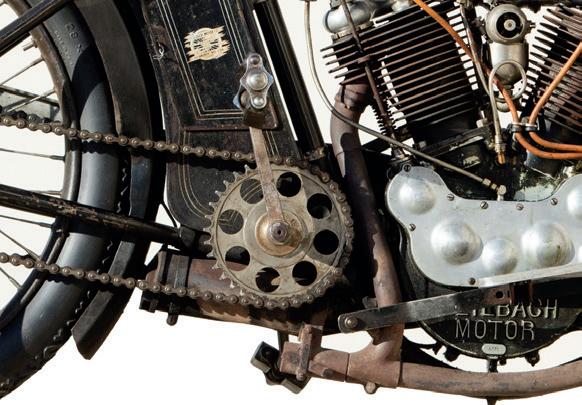

THE AUTUMN STAFFORD SALE

Sunday 15 October 2017

THE LAS VEGAS MOTORCYCLE AUCTION

Thursday 25 January 2018

THE PARIS SALE

Thursday 8 February 2018

COMPLIMENTARY AUCTION

APPRAISAL REQUEST

Visit bonhams.com/motorcycles to submit a Complimentary Auction Appraisal Request.

• WORLD RECORD PRICES

• EXTENSIVE CLIENT AUDIENCE

• INTERNATIONAL MARKETING

• INTERNATIONAL NETWORK OF SPECIALISTS AND OFFICES

ENTRIES INVITED FOR FORTHCOMING SALES

ENQUIRIES

United Kingdom

+44 (0) 20 8963 2817

ukmotorcycles@bonhams.com

USA

+1 (323) 436 5470 motorcycles.us@bonhams.com

bonhams.com/motorcycles

© 2017 Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp. All rights reserved. Bond No.57BSBGL0808 @bonhamsmotoring

1932 BROUGH SUPERIOR SS80 DE LUXE $70,000 - 85,000

1911 PIERCE FOUR $100,000 - 150,000

1913 HENDERSON 1,068CC FOUR $90,000 - 115,000

1914 EXCELSIOR SINGLE 2-SPEED $40,000 - 50,000

1949 VINCENT 998CC BLACK SHADOW SERIES-C $65,000 - 75,000

The ex Ivan Mauger, 1968 World Championship Speedway Final winning, 1968 JAWA SPEEDWAY RACING MOTORCYCLE $15,000 - 22,000

1969 MV AGUSTA 750S $65,000 - 85,000

1912 PIERCE 592CC SINGLE $50,000 - 65,000

The ex-Ivan Mauger, 1977 World Championship Speedway Final winning, 1977 JAWA SPEEDWAY RACING MOTORCYCLE $15,000 - 22,000

1932 BROUGH SUPERIOR SS80 DE LUXE $70,000 - 85,000

1911 PIERCE FOUR $100,000 - 150,000

1913 HENDERSON 1,068CC FOUR $90,000 - 115,000

1914 EXCELSIOR SINGLE 2-SPEED $40,000 - 50,000

1949 VINCENT 998CC BLACK SHADOW SERIES-C $65,000 - 75,000

The ex Ivan Mauger, 1968 World Championship Speedway Final winning, 1968 JAWA SPEEDWAY RACING MOTORCYCLE $15,000 - 22,000

1969 MV AGUSTA 750S $65,000 - 85,000

1912 PIERCE 592CC SINGLE $50,000 - 65,000

The ex-Ivan Mauger, 1977 World Championship Speedway Final winning, 1977 JAWA SPEEDWAY RACING MOTORCYCLE $15,000 - 22,000

VELOCETTE THRUXTON

A tale of two fishtails

Photos by Nick Cedar

Photos by Nick Cedar

AA family operation, for 65 years the Velocette factory built high-quality but quirky motorcycles in Hall Green, Birmingham, England. The two sons of founder John Goodman (formerly Gütgemann) had opposing personalities. Percy, a speed enthusiast, developed some of the best race bikes of the last century while Eugene, a proponent of economical transport, designed 2-strokes and overhead valve singles. Interestingly, the ancestor of the ton-up Thruxton, the 250cc MOV, was designed by Eugene.

Despite its small size, Veloce Ltd., makers of Velocette motorcycles, was known for its advanced technology. The first positive-stop, foot-actuated gearchange on a production motorcycle appeared on the 1929 KTT. But the KTT and other overhead cam Velos were expensive to build. After the Depression hit in the 1930s, a cost-effective alternative was needed.

Eugene Goodman responded with the high-camshaft 248cc MOV in 1933. It sold well, and a 349cc version, the MAC, and a 495cc version, the MSS, soon joined it. Continuing Velocette’s tradition of innovation, the 1935 MSS sported automatic ignition advance.

The defining feature of the MOV, and subsequent versions of its single-cylinder engine, was the valve train. The camshaft, sitting high in the cases, spun off a series of gears mated with the crankshaft, and short pushrods operated the rockers atop the cylinder. Keeping the cam high and the pushrods short lessened reciprocating weight and improved valve control.

18 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s

Story by Margie Siegal

In 1939, England plunged into World War II and civilian motorcycle production stopped. Velocette built some military motorcycles based on a 350cc version of the MOV, but did not receive large military contracts like BSA and Norton did. As the war ended, Velocette was weakened financially.

The seed is sown

1966 VELOCETTE THRUXTON

Postwar, small commuter bikes were supposed to be the coming thing, but Velocette’s innovative sidevalve horizontal opposed twin, the LE, although very popular with police departments, was not a success with enthusiasts. Fortunately, someone at Velocette realized that while the market for its docile little twin was soft, the market for sport machines was not. Although Velocette’s postwar plan had been to focus on the LE, production of the 349cc MAC was continued.

Mostly unknown in the U.S. prior to World War II, Velocettes were discovered by American soldiers stationed overseas during the war years. Jack Frodsham started importing Velos to the United States after the war, before selling his operation to Lou Branch in 1949. Velocette had phased out production of the 495cc MSS (and all other models besides the MAC and LE) after the war, but by the early 1950s both Frodsham and Branch were pushing Velocette to build another 500.

In 1953, Velocette introduced an updated swingarm frame for the MAC. Front suspension was by hydraulically damped telescopic shocks, and the rear suspension was easily adjustable for load by moving the top end of the shocks along an ingeniously designed slot. Velocette did not have the capital to redesign the new MAC frame to accept

the taller MSS engine, so factory engineer and designer Charles Udall reconfigured the MSS to fit. The result was a square 86mm x 86mm bore and stroke 499cc engine, unusual at the time. Not only did it fit in the existing frame, but it turned out to have better breathing and the capacity to rev higher than previous longstroke engines.

Introduced in 1954, the new MSS was quickly discovered by California desert racers. Jim Johnson won that year’s

Catalina Island GP on an MSS, and Velocette started producing a scrambler and an enduro version of its big single for the American market. Tex Luce successfully flat tracked a reworked enduro MSS built by Ernie Pico.

In 1956 Velocette brought out two sporty versions of the MSS: the 349cc Viper and the 499cc Venom. Evaluating the Viper in 1958, The Motor Cycle, one of the two English motorcycling weeklies, proclaimed it “a remarkably fine motorcycle,

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 21

At 499cc, the overhead-valve single produces 41 horsepower. The twin-leading-shoe drum front brake was king in its day.

all round performance well above the average,” and capable of 90mph-plus.

Both the Viper and the Venom had bi-metal cylinders, with a cast iron liner welded to an aluminum alloy jacket by the Al-Fin process. The heads were also aluminum, enclosing hairpin valve springs. The bottom end ran on tapered roller bearings, and lubrication was dry sump.

Venom, then Thruxton

The Venom, like all Velocettes, had its share of quirks. Chief among them was “The Starting Procedure,” the subject of a full paragraph in the owner’s manual and a process that had to be followed exactly or the bike would not start. Plate distortion could stop the clutch (which used multiple small springs) from lifting cleanly, and the magneto and generator ignition was hopelessly outdated. But enthusiasts didn’t mind, as the Venom was one of the best of the big British singles — fast, good handling and great looking.

In 1960, Velocette introduced the Venom Clubman, basically

a production racer with lights. It sported an Amal TT carburetor, a racing magneto and rearsets. By this time the third generation of Goodmans was running the show, including Bertie, son of Percy and a pretty good racer himself. A factory team took a Clubman to the banked circuit at Montlhéry outside Paris in 1961, and set 12- and 24-hour records of 104.66mph and 100.05, respectively.

In 1964, a racing cylinder head became available for the Venom. Possibly designed by Lou Branch, some sources state it was actually the work of Dick Brown at Modern Cycle Works in Los Angeles. It had a larger intake valve, a revised inlet tract and a narrower valve angle. Velocette built special gas and oil tanks, notched to clear the large 1-3/8-inch Amal GP carb the head used.

A Venom with the optional head won its class in the Thruxton 500-mile endurance race that year, and the next year, a new version of the Venom, the Thruxton, was introduced. Velocette claimed 41 horsepower at the crankshaft — 44 with a megaphone instead of a muffler. The American importer advertised it as “a man’s machine,” possibly because the starting procedure had gotten no easier over the years.

How to start a Thruxton

From the so-called “Red Book” Velocette service manual: “Turn on the fuel of both taps, and if the engine is cold, flood the carburetter. Some machines may need a little flooding even when hot to get a ‘first-kick’ start. Retard the ignition to approximately half the travel of the lever. Depress the kickstart crank until compression is felt. Release the crank and allow it to return to the top. Using the exhaust valve lifter control, press down the kickstart crank slowly to the bottom — no farther. After bringing the kickstart crank back to the top again, the engine is ready to start by using the kickstart without lifting the exhaust valve. One kick should suffice if the throttle has been set correctly. The throttle valve should not be opened more than approximately 1/16-inch when starting.”

The Thruxton had the standard Venom dual-loop frame with upgraded telescopic forks, clip-ons, rearsets and the Velo fishtail “Brooklands can” muffler. It was good for up to 110mph stock — and a lot more with knowledgeable tuning. With standard gearing, a Thruxton turned 4,000rpm at 70mph.

Later Thruxtons swapped the highstrung GP carb for an Amal Concentric, the compression ratio was raised a bit, and from July 1968 on a battery and coil ignition became available, which might have made starting a tad easier. Color was generally silver/blue, but customers could order their Thruxton traditionally finished in black with gold pinstriping.

Our bike

Our feature bike has a somewhat unusual background. Pat Peddicord was in the business of selling Velocettes in Southern California when he bought our silver/blue 1966 Thruxton feature bike from a customer in 1968. At the same time his son, Terry, was riding a black 1966 Thruxton.

22 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s

Want a Thruxton? Be ready to get real familiar with this kickstart lever.

Fast-forward to about 10 years ago when British motorcycle enthusiast Frank Recoder started looking for a Thruxton. About 1,058 Thruxtons were built in the five years of production (an estimated 60 more were assembled from original bits after Velocette went out of business in 1971), and these are now scattered around the world. Surviving Thruxtons are, not surprisingly, rare, and often get passed from one “Velocettista” to another, so Frank started working his way into local Velocette circles. Eventually, he got a lead on a silver/blue Thruxton, Pat Peddicord’s bike.

Pat had passed on, and his Thruxton belonged to his widow. “Pat had gone for a ride, parked the bike and collapsed. They found him too late,” Frank says. Although the bike had sat for seven years, the Peddicord family wasn’t sure they wanted to sell it, and it took two years for Frank to convince them he would care for the bike as Pat had. At that point, Terry mentioned he had a second Thruxton, apart and in boxes.

Frank took possession of the silver/blue bike (called Deep Blue/Metallic Silver by Veloce), which, while mostly complete, wasn’t running, and set to sorting it out. At first, Terry didn’t want to part with his black Thruxton, but then his wife had a baby, and some four months later Frank took possession of what he says was 70 percent of a Thruxton, including all the sheet metal. He called Velocette specialist Ed Gilkison, who’d helped get the silver/blue bike going, for help.

Ed did the machine work, located missing engine parts, and provided support, advice and encouragement for the project. Eight months after Frank bought the black Velo, it was back together. “Then it took me six months to sort it out and locate all the leaks,” he says.

Since getting both bikes going, Frank has more or less decided the black Thruxton is the rider and the silver/ blue bike is the show bike, although he did show the black bike at the 2012 Quail Motorcycle Gathering. This past summer, Frank and his wife, Elizabeth (an enthusiastic pillion rider), rode the black Thruxton to the annual Velocette rally in Arizona. “Five days of riding — 1,000 miles!” Frank says, smiling at the memory.

Frank says owning and maintaining a Thruxton isn’t too bad, but setting up the clutch is tricky. “It’s unusual — very thin. It has two plates that slide and three driven plates. You have to adjust it by turning the spring-loaded center. The engine has to go through a cycle before the clutch opens. You have to watch first gear and time gear changes or the transmission will make noise. But once it’s set up it works fine. I set the clutch on the silver Thruxton 3,000 miles back and it still works fine.”

Like all vintage bikes, oil changes are frequent on a Thruxton. “I change the oil every time I come back from a rally. I used to put hypoid gear oil in the transmission, but I had problems with a leaky tranny. I read an article in the Velo club newsletter that recommended lighter oil. Oil is kept in the transmission by deflection washers; the return holes are small, and thick oil will clog the holes. I use 50 weight Motul now,” Frank says.

As much as Frank likes his Thruxtons, they aren’t without challenges. Difficult to start when cold, the GP carb has no idle circuit, so once you get a Thruxton started, you have to rev it until it is warm. Frank says it takes five minutes, but after it’s warm, it’s a sweet engine with a wide powerband and loads of torque. “I normally rev the engine to 5,000rpm,” Frank says. “Max is 6,200rpm. It holds its line on twisties — I can maintain speed, switching from second to third gear and back. It has plenty of power. I can really feel it pulling out of corners. It’s unique — a pleasure to ride and a nice rush. The bike responds to you and repays all the work you have to put into it. Thruxtons are racers. Once you find that sweet spot, about 70-75mph, you can go forever.”

These two 500cc Velocettes are part of two families’ histories and another family’s present. Designed and built by the Goodman family in England, and owned, ridden, repaired and loved for years by Pat Peddicord and his son, Terry, stalwarts of the postwar Southern California motorcycle scene. The Goodmans no longer build bikes, and Pat Peddicord is gone, but these rare classics are still here, now owned by Frank and Elizabeth Recoder, who treasure them both. MC

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 23

Owner Frank Recoder enjoys riding both his Velocette Thruxtons, though he’s decided the silver one is the show bike and the black one is the rider.

“Then it took me six months to sort it out and locate all the leaks.”

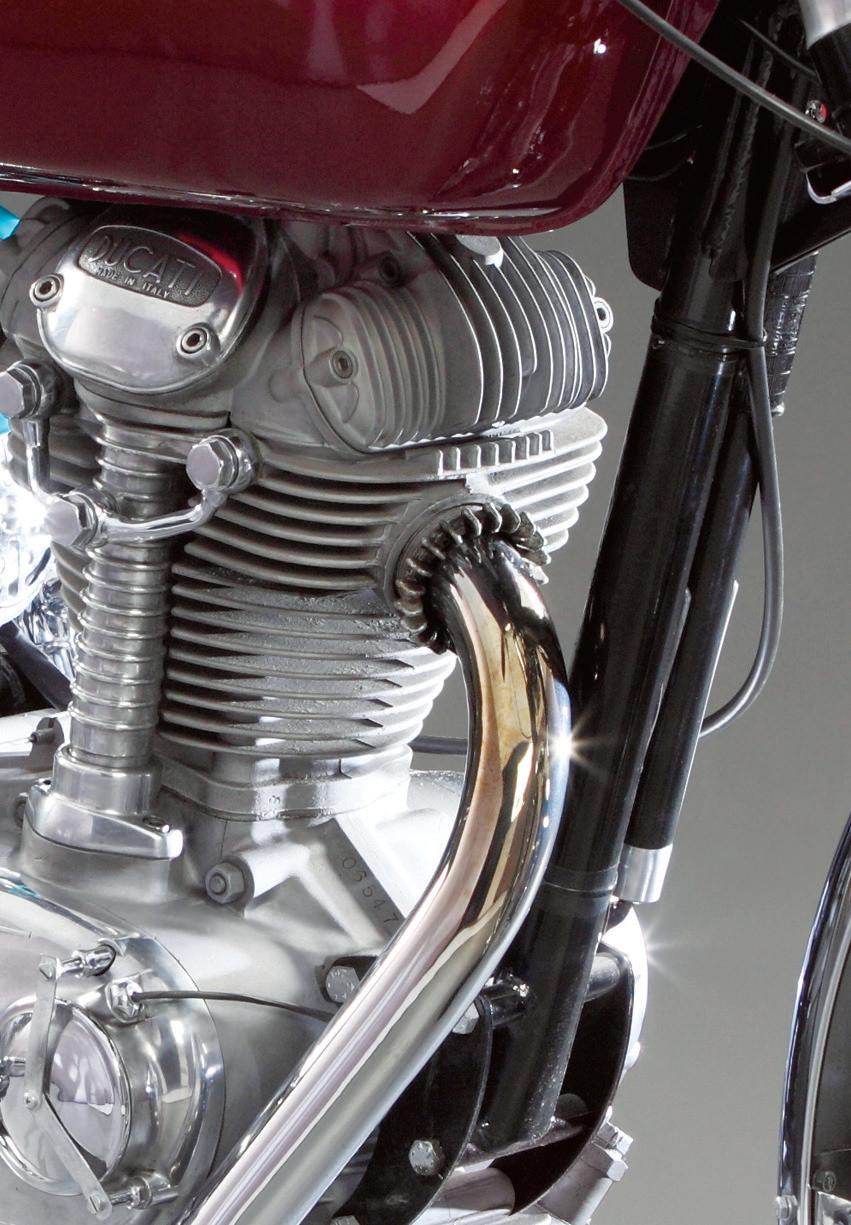

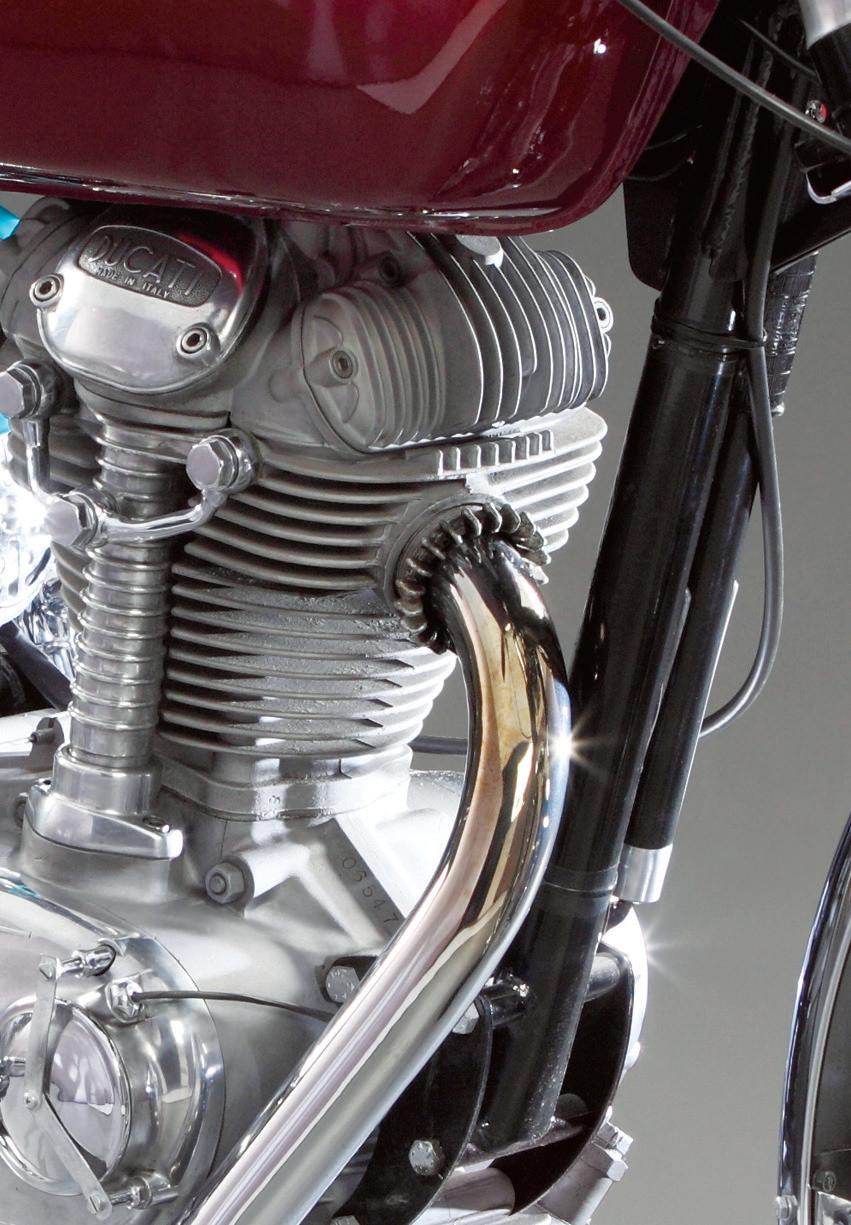

“D” FOR DESMO

1969 Ducati 350 Mark 3 D

Story by Greg Williams

Photos by Jeff Barger

1969 Ducati 350 Mark 3 D

Story by Greg Williams

Photos by Jeff Barger

It’s a long transition from a Doodlebug scooter to a 1969 Ducati 350 Mark 3 Desmo. In fact, it would be difficult to find a better example of two-wheeled evolution — from antiquated to advanced.

Doodlebug, a little scooter with a Briggs & Stratton 1-1/2 horsepower engine and diminutive tires. His Doodlebug was direct drive, missing the fluid clutch it would have had when delivered new from the Beam Manufacturing Co. of Webster City, Iowa. At stop signs and red lights he would lift the rear wheel, then, with the intersection clear, he’d drop the back of the scooter and open the throttle. Don wasn’t going anywhere fast.

He was just 13, and the Doodlebug, his first ride, was freedom. Don’s never been without a motorcycle since. Over the years he’s owned different makes including Harley-Davidson, Honda, Moto Guzzi and Triumph, but he has a soft spot for Italian products.

A retired ironworker, Don worked building bridges and towers in his home state of Wisconsin. Some 13 years ago, he turned his attention to motorcycle restoration. “My son, Scott,

found a 1966 Ducati Monza Jr. 160 and said he’d like to restore it,” Don says. “But he didn’t have time and I’d just retired, so I took over the job — that was my introduction to complete restorations.”

Don’s motorcycling history is quite interesting. His first “big” bike was a HarleyDavidson K model. But his friends were all riding British, so he bought a brand new 1960 Triumph TR6, which he then traded in 1965 for a Bonneville. When he heard about the Honda CB750 Four in 1969, his name was second on the list at the local dealer. He bought another CB750 in 1971, followed by two Suzuki GT750s — a 1972 and then a 1973 — before buying a Kawasaki 900 in 1974.

“The Kawasaki went fast in a straight line, but it wiggled around the corners,” Don recalls. “I preferred handling over straight-line speed, so in 1975 I got a Moto Guzzi 850T, and then traded that in 1977 for a Moto Guzzi LeMans. I didn’t think anybody could build anything better than that, and I still have that bike.”

Every two or three years, he’d buy or trade up, and if he had any emotional attachment to a motorcycle, he’d keep it — witness the LeMans and his 1992 900SS Ducati, which now shows 55,000 miles on the clock. There are currently 18 machines in his collection, and one of them is this 1969 Ducati 350 Mark 3 D.

Taglioni’s designs

The Mark 3 D is about as far from a Doodlebug as one can get, and the difference in technology is thanks to Italian designer Fabio Taglioni. In 1949, Taglioni sketched a 75cc double overhead cam engine as a design exercise while studying for his doctorate at the University of Bologna. He sold the resulting engine plans to Ceccato, and then studied for two years under Alfonso Drusiani at Italian motorcycle manufacturer Mondial. Taglioni joined Ducati in 1954, and his first design was the 98cc bevel gear overhead cam Gran Sport, which was nicknamed “Marianna” in Italy.

Taglioni’s Gran Sport proved competitive in Italian race events during the mid1950s, sweeping its class at the MilanoTaranto and the Giro d’Italia races. Grand Prix racing was next, and Taglioni’s design brief netted a 125cc double overhead cam

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 25

Like the rest of the little Ducati, even the heel/toe shifter is slender and graceful, a promise of pleasure.

single. Although reliable, the engine wouldn’t rev high enough to make decent power. Allowed to rev out at 11,500rpm, the valves would float and hit the piston crown. Looking for a solution, Taglioni settled on desmodromic valve actuation.

Overhead valve engines use a cam or pushrod and rocker to open the valve but rely on spring pressure to force the valve closed. Desmodromic engines instead use separate rockers — one to push the valves open and another to pull them shut. This helps avoid problems such as valve float and valve spring failure. Taglioni did not invent the desmodromic valve concept, and the technology has been around since the early years of the 20th century. Other motorcycle engine designers tinkered with the approach, including Norton and J.A. Prestwich. In the mid-1950s, automobile manufacturer Mercedes-Benz famously and successfully campaigned desmodromic valve engines in the W196 racer.

1969 DUCATI MARK 3 DESMO

Desmo debut

With desmo actuation, Taglioni’s single could cleanly rev to 12,500rpm, and in 1956, the 125cc works racer took the win in its debut at the Swedish GP. Although the desmo was successful at the track, Ducati’s road-going singles used bevel drive overhead camshafts and rockers, with enclosed hairpin valve springs. This engine style became widely known as the “narrow case” design, with front and rear engine mounts the same width. Ducati singles grew from 100cc to

125, 160, 200, 250 and 350cc models, and of them all, the most memorable would be the 250 Mach 1.

In 1967, Ducati launched a redesigned frame featuring twin tubes running from the back of the gas tank down to the swingarm pivot. This new frame required a wider rear engine case mount — approximately 3 inches wider than the front — and these subsequently became known as “wide case” engines. Between the two styles, narrow and wide case, the basic architecture remained the same.

Ducati brought the new frame and wide case engine design to the street in 1968, first in the street-legal 350cc Scrambler, then also in 250cc and 450cc models. All of these used a bevel drive overhead cam with valve springs. During 1968, Ducati finally brought a desmo to the street with the launch of the 250 and 350 Mark 3 D — “D” for Desmo.

The 1968 Ducati Mark 3 D featured a red frame, a red and chrome gas tank with twin-filler caps, chrome fenders, steel rims, a high-lift cam and a tachometer. In 1969, the 250 and 350 were joined by a 450 Mark 3 D, and they were outfitted with a black frame and a single-cap fuel tank and chrome fenders. Non-desmo Ducatis feature a dull silver paint in place of the chrome.

Ducati’s 350cc single-cylinder desmo engine is all alloy with polished cases and massive finning on the barrel, which features a cast-iron liner. Bore and stroke are 76mm by 75mm for a capacity of 340cc, with a 10:1 compression ratio. The 5-speed unit construction gearbox has a heel/toe shifter on the right side of the engine, with the kickstarter on the left.

Cycle magazine tested the Mark 3 D Ducatis, including the 250, 350 and 450 models, which, apart from engine size, are of the same overall dimensions. “The Ducati’s single-cylinder engine has narrow cases; therefore, the frame, the tank and the footpegs can all be very narrow, too. You can fit yourself more easily to a well-

laid-out narrow motorcycle than you can to the fat bikes, and the result is a feeling of instant confidence … the Ducatis feel as though they had been built just for you, and that they weren’t something that came out of a crate,” Cycle said.

Of the 350cc desmo engine, they wrote: “The 350 was more highly tuned and had a narrower powerband; the power came

driven to the event, as he had no plans to purchase a motorcycle. Luckily, friend Erik Eskildsen was driving through to Florida with his truck. He told Don if he found something he couldn’t live without he would haul it south with him, and bring it home to Wisconsin in the spring.

Don was drawn to a Benelli being sold by father and son team Dwight and (the late) Brian Corley. The Benelli was already spoken for, but then he noticed a Ducati single-cylinder engine.

“The head had been removed,” Don says. “Dwight told me the desmo head was good, but the engine was seized.” Dwight picks up the story. “My son and I were mostly into British bikes, but we heard about this Ducati in Georgia, so we went to have a look at it — it had seen years of exposure, but we picked it up thinking we might be able to redo it. The more we looked at it the more we thought somebody else could probably do something better with it.”

in at about 6,500rpm. The 350 is tuned as a street dragster; the 250 and the 450 are over-the-road bikes.”

Don’s 350 D

Don found his 1969 350 D at the 2010 Barber Vintage Festival swap meet in Birmingham, Ala. He and a friend had

The rest of the bike was stored in the Corleys’ trailer behind their camper. “The bike was a wreck,” Don explains. “The wheels were frozen and badly rusted, the alloy hubs were crusty and the entire bike was rusty. There was a dented Ducati Scrambler tank and a high handlebar on it.” However, because it had a Desmo engine, Don paid the Corleys $1,500 and had Erik haul it home to Appleton, Wis., by way of Florida. Don didn’t get to work on the bike until

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 27

The desmo singles are all based on the “wide case” block.

the spring of 2011. Stripping the Ducati down proved the frame was straight, but the swingarm pivot bolt was rusted in place. Don drilled small holes in the back of the swingarm and filled the cavity with penetrating oil. “I had a punch the exact size of the shaft, and every so often I’d give it a crack. After two months, it finally moved,” Don says.

With help from Jonathan White of Prova LLC in Cincinnati, Don began accumulating the correct pieces for his 350 D, including a coffin-style tank and the correct steel front fender, both sourced on eBay. The fenders, springs, kickstarter and shift lever were chrome-plated. The frame was powdercoated black, and Bryan Gagnon of B&J Custom Cycles & Graphics in Shawano, Wis., finished the gas tank and side panels cherry red, a hue Don says is slightly darker than what Ducati would have used. The bike was missing its seat, so he found a used seat pan and had a new cover stitched by Korth Upholstery in Appleton. Don polished the alloy wheel hubs and laced them to 18-inch stainless steel rims with stainless spokes. As for the engine, Don says he couldn’t have completed the build without help from friend Erik King. The lower end proved to be in fine fettle, but while it was apart everything was

polished, and the crankshaft was treated to new bearings. A used muffler and header pipe came from eBay, and both were chrome-plated after Don removed the muffler baffle. On the 1969 350 D the correct carburetor is a Dell’Orto SS1 29D,

and Don’s machine is so equipped. Chris Dietz of Motion Products in Neenah, Wis., rebuilt the Ducati wiring harness, Don detailed the hand controls and levers, and new rubbers and cables completed the build.

The finished product

“It was scary to fire it up for the first time,” Don says. “You’ve got to kick it deliberately, because it’s got great compression and will kick back. They’re all a bit different to start, and I haven’t got this one down quite yet, but it did start on the fourth kick and it’s been running good since. You can just about feel the piston going up and down when the bike takes you forward, and it handles great. You can carry a lot of speed into a corner because it’s so light, and that really makes it fun to ride. The brakes are a bit weak, but because the bike is light they’re really not a big issue.”

Don restored his Ducati using original components, and with the materials that were available when the machine left the factory, as much as possible. “I want to transport myself back to that time, and I restore them so I can appreciate what I used to ride,” Don explains, adding, “I restore them to preserve an old bike, not to make an old bike modern.” MC

28 Motorcycle classics Street Bikes of the ’60s

Owner and restorer Don Smith with the Ducati, one of a growing collection.

© PIAGGIO GROUP AMERICAS 2017 MOTOGUZZI.COM

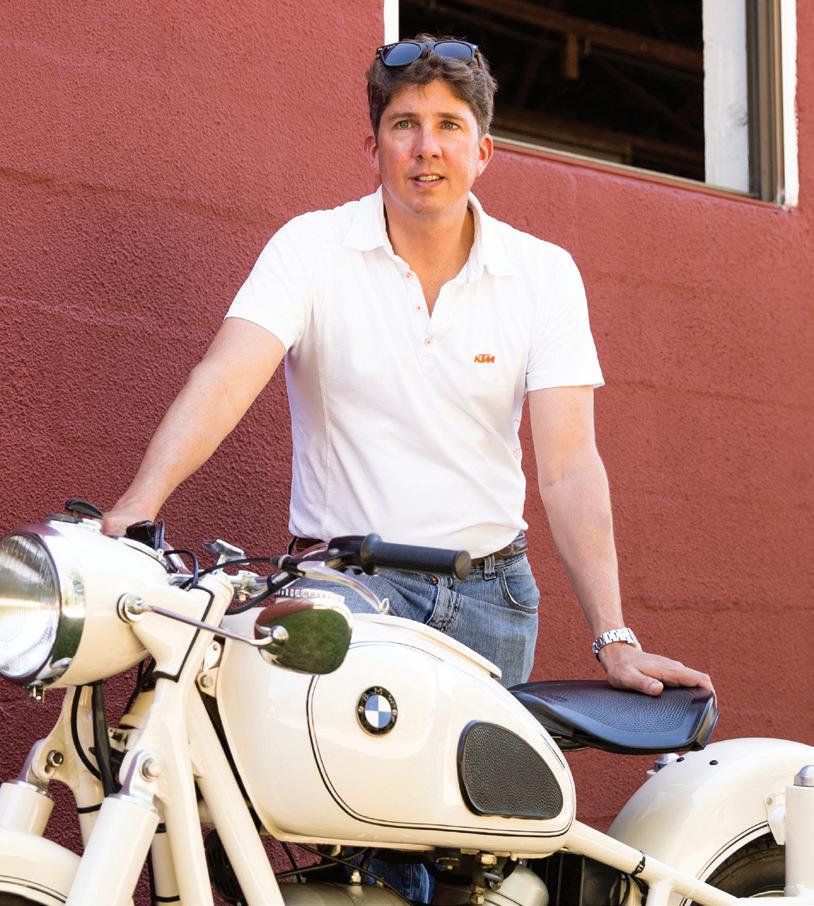

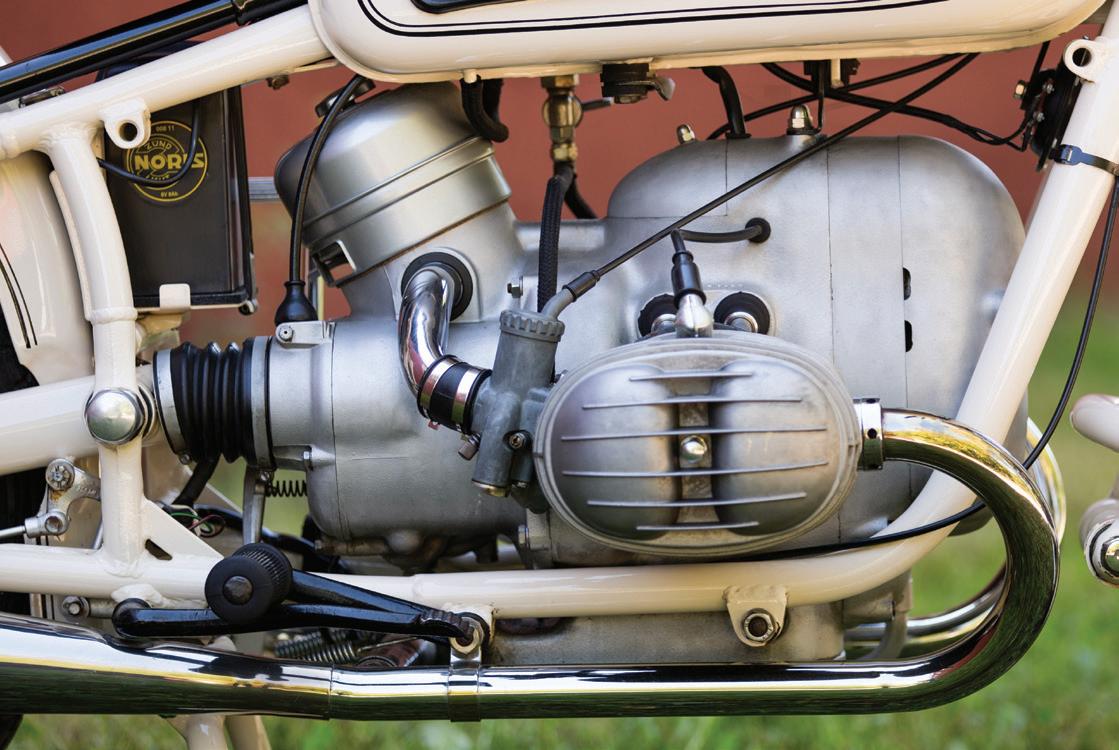

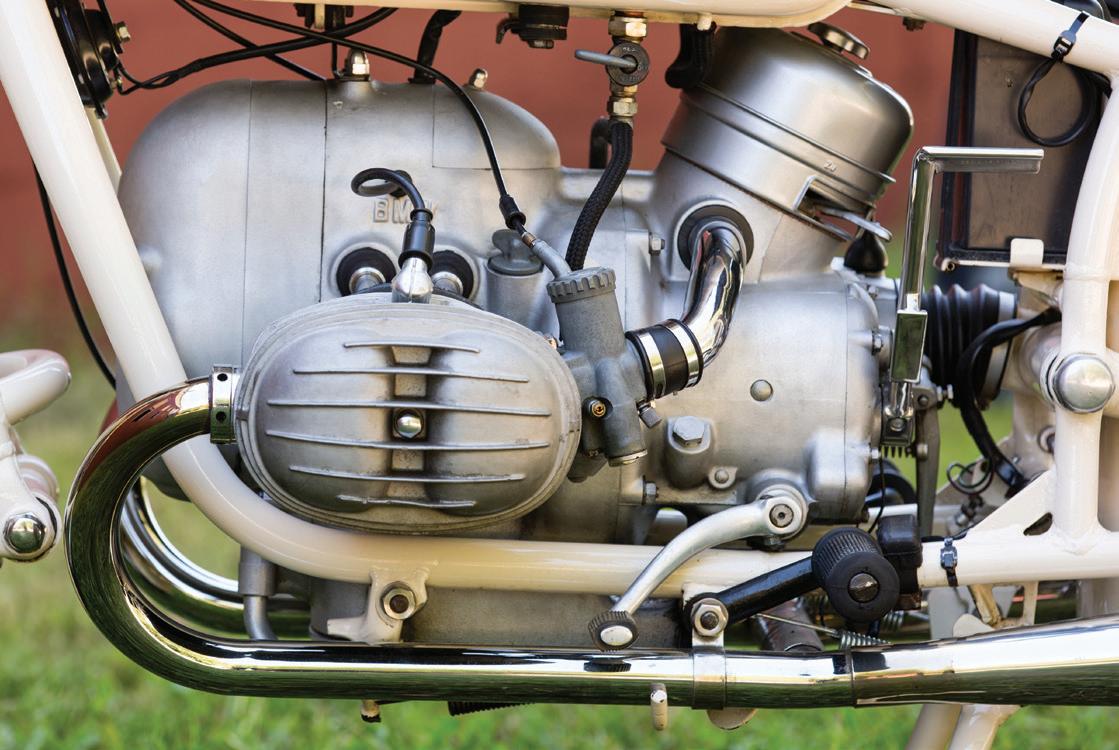

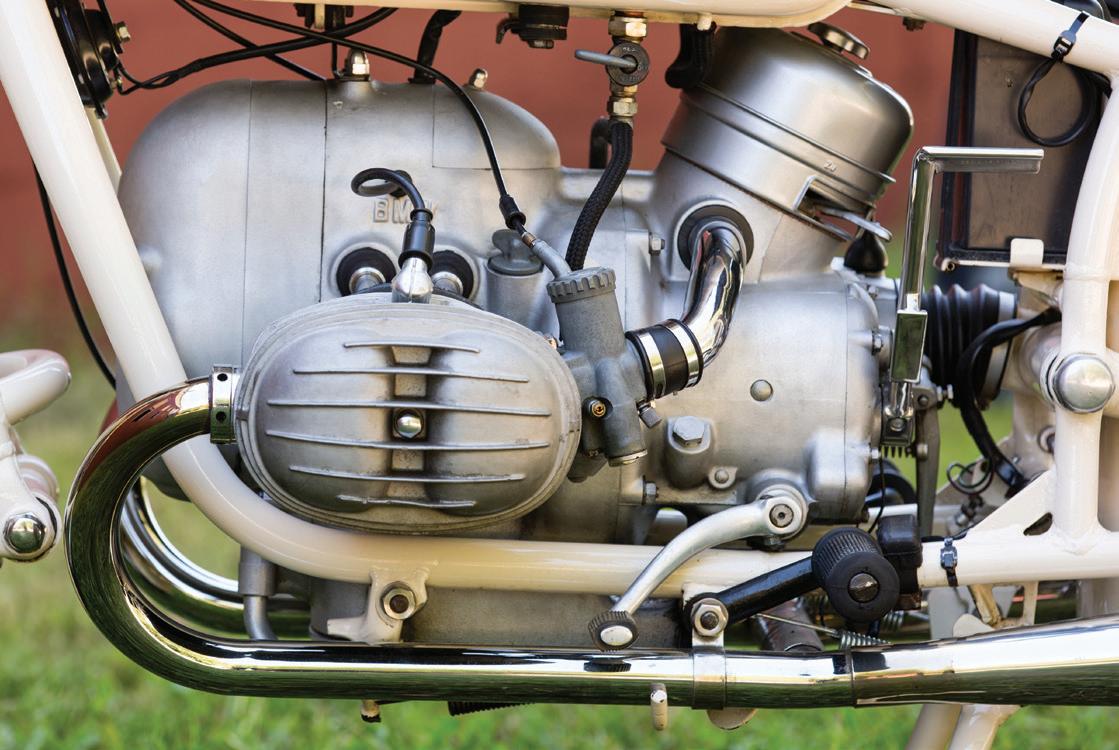

ELEGANCE IN MOTION

1962 BMW R60/2

Story by Greg Williams

Photos by Ken Richardson

Photos by Ken Richardson

TThe Apple computer I’m using as I write this story and its subject matter, a BMW R60/2, have something in common. In the early 1980s, long before Apple and its iProducts were household names, Steve Jobs, the enigmatic mind behind the company, rode around San Francisco on a 1966 BMW R60/2.

When Jobs wasn’t riding it, the BMW was parked in Apple’s atrium lobby. Walter Isaacson, author of the 2011 biography/autobiography Steve Jobs, wrote, “Over time, the atrium attracted even more toys, most notably a Bösendorfer piano and a BMW motorcycle that Jobs felt would inspire an obsession with lapidary craftsmanship.” The word “lapidary” has a couple of definitions, one of them being “careful, elegant and dignified in style.”

It’s clear that Jobs felt classic BMW motorcycles offered refined elegance and dignified grace, especially in the case of machines built in the 1960s. In this era, BMW offered multiple models, including the R50/2, R60/2 and the R69S. All of these machines shared the same chassis, but were powered by either 494cc or 594cc engines in different states of tune.

Between 1955 and 1969, BMW built the low compression 500cc R50, the high compression R50S, the low compression 600cc R60, and, as introduced for 1956, a high compression R69. Technically, only machines constructed from 1960 to 1969 carried the /2, or “Slash 2,” designation. 1967-1969 telescopic fork versions of the R50, R60 and R69 all carried the “US” designation instead of Slash 2 as they were for the U.S. market only. Now, however, many enthusiasts refer to the entire series as Slash 2s. Thanks to their stout and rigid double-loop steel frames with sidecar mounting points, these BMWs were commonly hitched to chairs.

30 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s

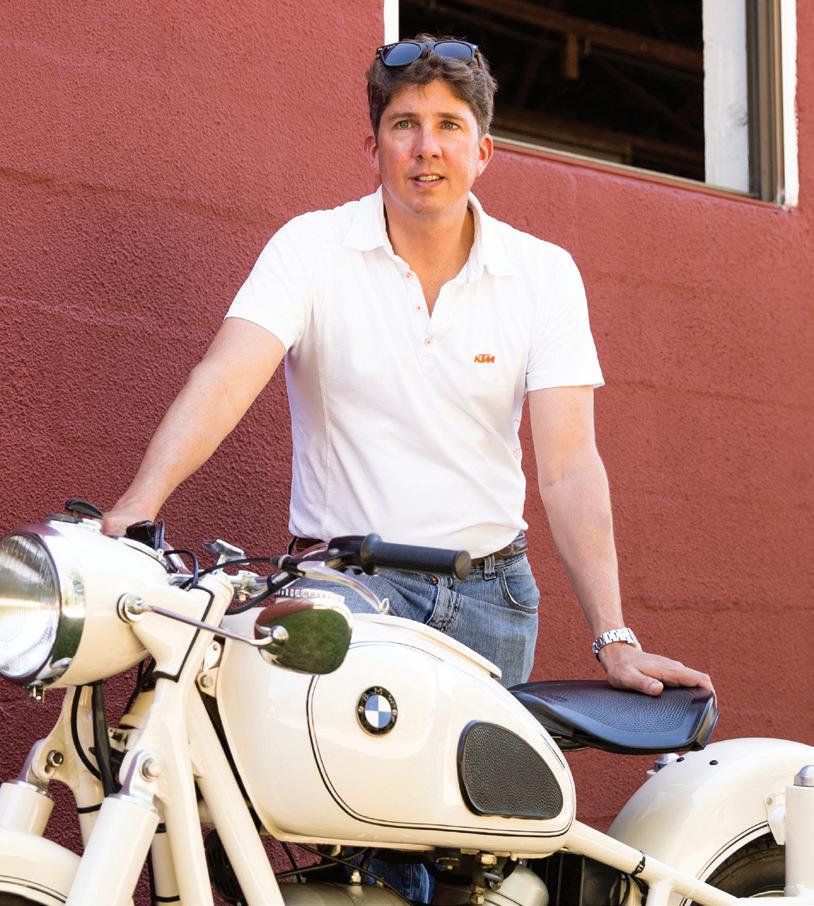

Best of the bunch

According to Philip Richter, a New York-based BMW aficionado and owner of the 1962 BMW R60/2 gracing these pages, the R60/2 is the best of the bunch. “My opinion is subjective, of course,” Philip says, acknowledging his owner bias, “but the R60/2 has a Zen-like balance. It’s true the R69S motor delivers more horsepower, but it’s heavier. The power-to-weight ratio of the R60 is superior to either the R69S or the R50. I own all three versions, and the R60 is the best of that ilk.”

Philip comes by his fascination with German motorcycles quite honestly. His dad, Max Richter, grew up in postwar Germany and rode a small Zündapp motorcycle. It made quite an impression as he spoke of it often, and with great

affection. When Philip was 7 he was given a 1977 Honda Z50, which he used to blast around the Bedford, New York, horse farm where he grew up. He and his brother Hans eventually built a motocross track, and moved up to larger machines. Philip never thought about a street-going motorcycle until 1992. That’s when he was enrolled at Boston College in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. “In your junior year they make you live offcampus, plus there’s just no parking anywhere to be had,” Philip recalls. “So, I decided to buy a motorcycle to make the 3-mile commute, because there was no reliable public transit where I lived. I used to ride straight up to the O’Neill

1962 BMW R60/2

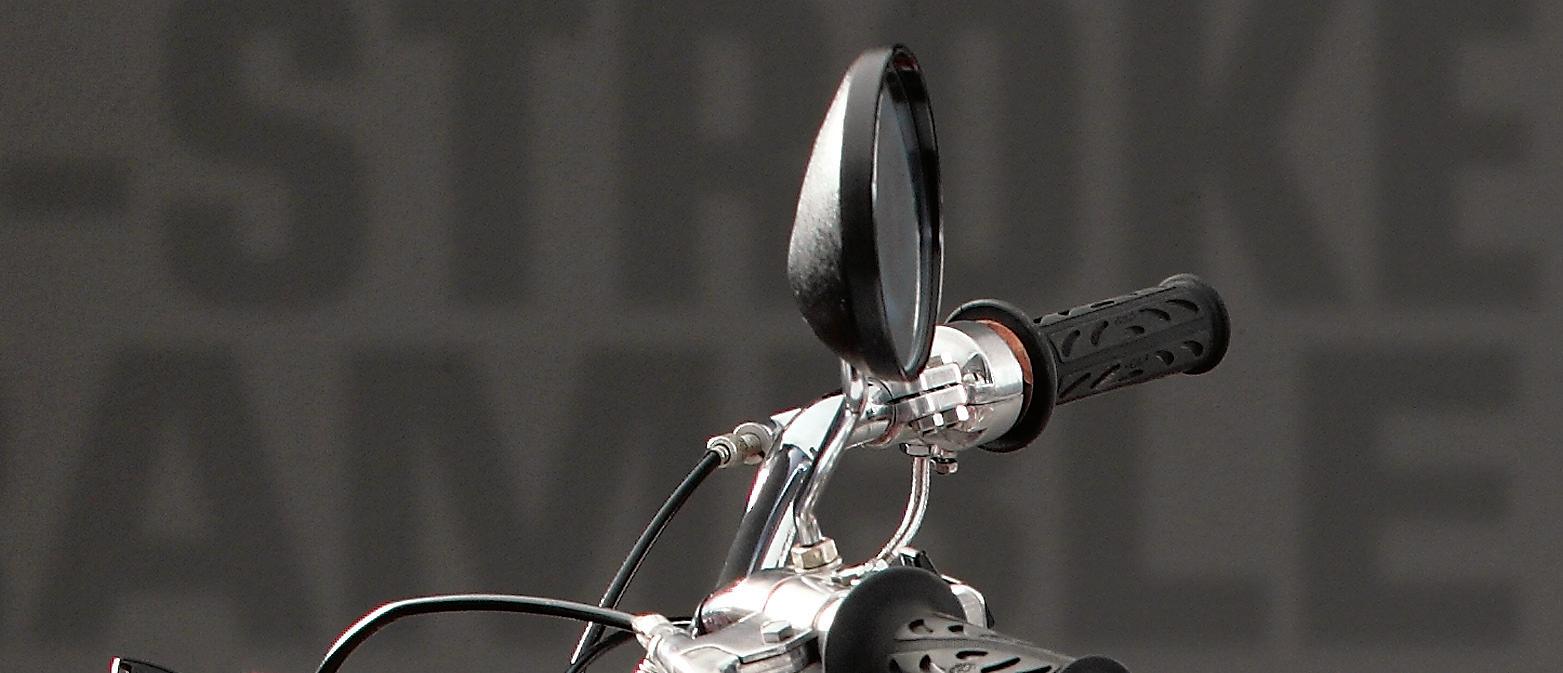

The Albert mirrors are a period accessory (far left). The tool kit hides in a recess in the fuel tank.

1962 BMW R60/2

The Albert mirrors are a period accessory (far left). The tool kit hides in a recess in the fuel tank.

Library and leave my bike there and head off to class.” His machine of choice was a brand-new 3-cylinder 1992 BMW K75S. “At the time, my brother had an R90/6. I loved the look of that air-cooled bike, but at 22 years old I wanted something sportier.”

The K75S served Philip well, and he treated it with respect. Phil Cheney at the now-defunct BMW Lindner Cycle Shop in New Canaan, Connecticut, took care of routine maintenance and repairs on Philip’s bike. “Whether it’s a model built in 1923 or 2015, he’s a genius and simply loves BMWs, but he particularly appreciates vintage BMWs,” Philip says of Phil’s expertise.

Vintage vibes

Through Phil’s influence, Philip’s interest in vintage BMWs began to blossom, and in 2000 he bought his first — this 1962 R60/2. It was completely restored by its previous owner, Bill Dauphinais, with Phil’s help. Bill took the BMW apart in his basement, and had Phil take care of the more intricate pieces such as the engine, transmission and rear drive.

Bill looked after all other aspects of the rebuild, with the exception of spraying the Dover white paint. That paint, Philip says, is “buttery thick with a high gloss; it’s just exquisite.”

Although it seems like most Slash 2 BMWs were painted black with white pinstripes, that wasn’t always the case. According to BMW enthusiast Jeff Dean, who runs the bmwdean.com website, the Dover white color came about thanks to U.S. BMW importer Butler & Smith’s Michael Bondy. Apparently, he sent a can of the white paint that was used on his vintage Packard to BMW, who were able to reproduce the color. With that, Bondy ordered 50 BMWs in Dover white.

Another feature of the Slash 2s that made them a popular sidecar hauler is the Earles front fork. A leading-link design developed by Ernest Earles and patented in 1953, the Earles fork doesn’t dive under braking (actually, the bike tends to lift from the forward weight transfer induced under braking) and is stronger than a conventional telescopic design.

It has dual oil-filled shock absorbers with springs, and the swingarm features two pivot positions for either solo or sidecar riding. A noted feature of the Earles fork is its extreme rigidity.

All Slash 2s featured BMW’s aircooled boxer engine — so called because its horizontally opposed pistons move apart and together at the same time. Legend has it that Adolph Hitler coined the phrase while visiting a BMW engine factory because the

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 33

Owner Philip Richter and his lovely Dover white 1962 BMW R60/2.

moving pistons looked to him like a boxer slapping his gloves together. The boxer engine design has long been appreciated for smooth running thanks to its almost perfect primary engine balance.

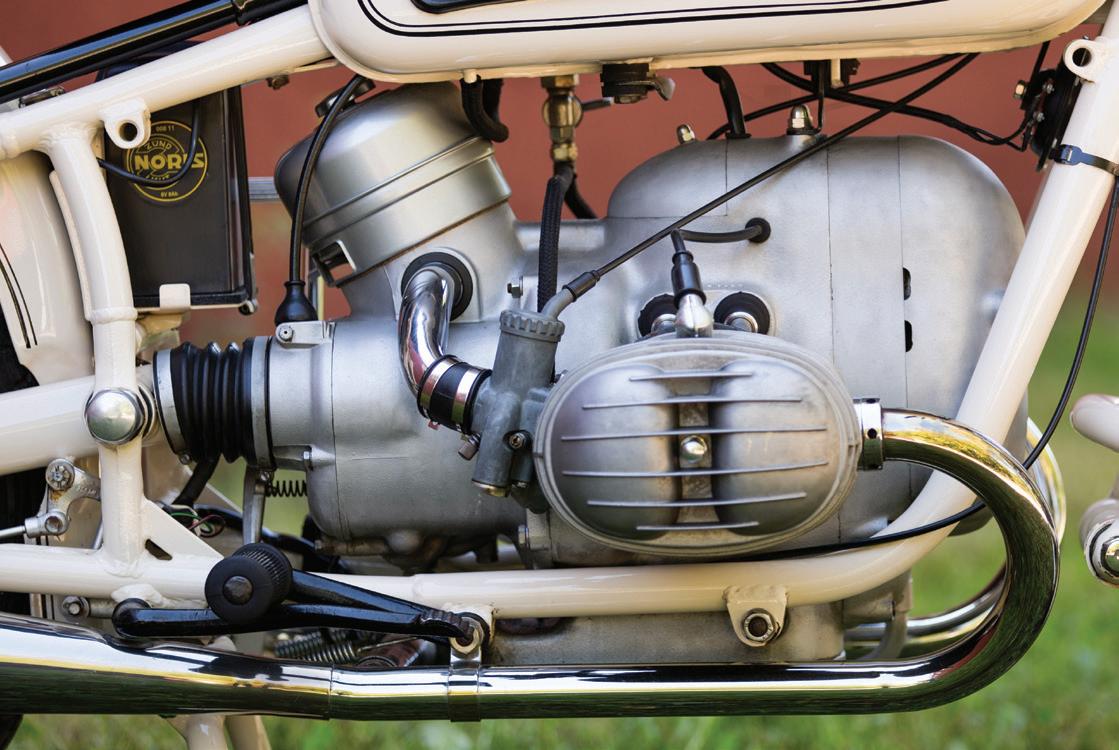

According to Jeff Dean’s information, BMW produced just 700 R60/2s in 1962, its first year of manufacture, with a total of 16,870 built over its 1962-1969 lifespan. The R60/2’s engine has a bore of 72mm and stroke of 73mm, giving almost square dimensions and a total of 594cc.

Compression is 7.5:1 and the engine makes 30 horsepower at 5,800rpm. A Bosch magneto provides sparks and is independent of the rest of the electrical system, although it resides under the front engine cover along with the 6-volt Bosch generator. The timing gears and oil pump are also at the front of the one-piece engine case, which features a carlike oil pan at the bottom.

The cylinders are cast iron, topped with aluminum cylinder heads featuring a single intake and exhaust valve each. (As a note of interest, the valve covers on both the R50/2 and R60/2 have six horizontal fins — the higherhorsepower S models have two cooling fins per cover.)

Exposed pushrod tubes run above the cylinders, with rubber seals at the crankcase side and press fit at the top of each cylinder; an oil return passage on the underside of each cylinder lets oil drain back into the crankcase. Carburetors on the R60/2 are a pair of 24mm Bing “Spezials” with integrally cast float chambers. The carbs are flange mounted and set at a 15-degree angle toward the engine.

A single dry-disc clutch connects the engine and 4-speed transmission, while a driveshaft, a BMW hallmark since the R32 of 1923, delivers power to the rear wheel. The enclosed driveshaft runs in oil in the right side of the swingarm. Properly maintained, the engine and drive system are very oil-tight.

The rear shocks are oil-filled and spring loaded and are virtually the same as the front shocks suspending the Earles fork, with the exception of spiral adjusters built into the lower shock housings to alter preload for solo or two-up riding. Up front, brakes are full-width twin-leading-shoe and the rear is a full-width single-leading-shoe. The 2.15 x 18-inch 40-spoke wheels spin on tapered roller bearings, and are interchangeable front to rear.

34 Motorcycle classics Street Bikes of the ’60s

Ready to ride

“Bill finished the restoration of the R60/2 in 1995, and kept it for five years,” Philip says. “He had retired and was moving to Arizona, and I managed to swing a deal for close to $6,500 for the bike.” When Bill restored the BMW he opted to fit deeply flanged alloy rims and the lower Euro-spec handlebar. Slash 2s destined for the U.S. came with a taller, braced handlebar.

For several years after buying the R60/2, Philip rode the bike as much as possible, and would go just about anywhere on it. The odometer currently reads 62,500 miles, but it wasn’t reset during the restoration and Philip’s unsure how many of those miles he’s actually accumulated.

Philip has made a few changes since acquiring the BMW. He added the period accessory Albert mirrors that attach to either side of the headlight, and when the original exhaust system rotted out he upgraded the pipes and mufflers to stainless steel. Philip laments the fact the exhaust is not authentic, but he’s happy he doesn’t have to worry about the system rusting out. Also, Phil Cheney thought the Pagusa rubber solo saddle should be changed to a Denfeld, so Philip made the switch.

In the interest of safety, Philip updates his tires every three years. “I’m in the wealth management business,” he says, “so for me, motorcycling is all about managing risk. When it comes to tires, I don’t cut corners.” He keeps the valves adjusted and the oil changed. “Other than that, the bike just runs. I think I could get on it and ride to San Francisco without it missing a beat.”

So, having said that, what’s it like to ride? After opening the single petcock on the left

side of the gas tank (BMW offered the R60/2 stock with a 4.5-gallon tank, or an optional 6.5-gallon vessel — Philip’s has the larger of the two) and tickling each carb for about three seconds to allow gasoline to raise the floats, Philip says it takes just one very light kick on the left side starter for it to fire up.

“On the road, this bike generates a lot of acceleration and power, and it doesn’t mind being pushed into the higher rev-range,” he says. “I can keep up with all of the modern bikes, but the biggest issue with the older machine is stopping — it just doesn’t stop that quickly. The transmission is silky smooth shifting, and when you’re cruising the whole affair is an effortless flutter amid a symphony of beautiful sounds.” Looking back, perhaps that’s why Steve Jobs included the grand piano beside his Slash 2 in Apple’s lobby. MC

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 35

The 594cc horizontally opposed twin produces 30 horsepower at 5,800rpm. The left-side kickstarter is visible behind the airbox.

Philip’s R60/2 wears the optional 6.5-gallon fuel tank. Turn on the fuel, tickle both carbs, give it a kick and you’re ready to go.

“I think I could get on it and ride to San Francisco without it missing a beat.”

MADE LIKE A GUN

1963 Royal Enfield Interceptor

Story

Story

WWhen I was in high school 45 years ago, there was an older kid who was unremarkable except that he owned two Royal Enfield Interceptors. That made him cooler than cool, because the merely cool rest of us rode more common British bikes or maybe something Japanese.

Greg Lawless bought this 1963 Interceptor for $500 in May 1973 as a college graduation present for himself. I suspect he experienced an immediate spike in his coolness. Over the last 42 years — including six moves involving three states — Greg’s put lots of miles on it and made many memories with it. Though his current collection includes 26 motorcycles, Greg says the Interceptor is the last bike he’d sell.

A little background

Royal Enfield was founded in the 1890s in Redditch, England, (just south of Birmingham) by two bicycle manufacturers who also made interchangeable gun parts for the Royal Small Arms factory in Enfield. For its logo, the new company chose an artillery field gun.

Royal Enfield’s first motorized bicycle, built in 1901, was followed by models incorporating such innovative features as crankcases with integral oil tanks (1903) and rubber “Cush Hub” drives to reduce chain snatch (1912). Royal Enfields were the first English production motorcycles with dry-sump lubrication systems and gear-type oil pumps (1913). The “Super 5” model, launched in 1961, was the first British production motorcycle with a 5-speed gearbox.

In 1948, the company launched the model that was to become synonymous with Royal Enfield: the redesigned overhead valve single-cylinder Bullet. This robust and versatile machine was utilitarian but also excelled as a competition motorcycle, especially in trials events.

Although Enfield ceased U.K. production of motorcycles in June 1970 to focus on military contracts (Royal Enfield had been making aircraft and guided missile components as well as motorcycles), Enfield Bullets are still being made in India, mak-

ing Royal Enfields the longest continually produced motorcycles in the world.

Though never as large as BSA, Triumph or Norton, Royal Enfield had an advantage: Its small senior management team included enthusiastic motorcyclists and former competitors who knew what riders wanted. They fostered new ideas and encouraged the introduction of models known for innovative design and robust construction.

The Big Twins

Royal Enfield launched its first parallel vertical twin in 1948, with a 64mm by 77mm bore and stroke and 25 horsepower. The basic design of the 500 Twin was to be carried through the subsequent, larger displacement models and included a long stroke for low-end power, a one-piece cast iron crankshaft, and separate cast iron barrels with aluminum heads and short alloy pushrods riding on a pair of camshafts.

Advanced features for the time included a full-flow oil filter

36 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS Street Bikes of the ’60s

by Corey Levenson

Photos by Jeff Barger

and semi-unit construction, with the gearbox bolted to the rear of the engine. The frame was welded steel with a single downtube attached to the front of the engine-gearbox unit, which acted as a stressed member. The swingarm rear suspension was a first for a parallel twin.

In 1953, the Meteor 700 was introduced as Britain’s biggest parallel twin — BSA and Triumph offered only 650s at the time. The 36 horsepower, 693cc Meteor was primarily intended to meet the needs of the sidecar market. It was essentially a “DoubleBullet,” each cylinder having the same bore (70mm) and stroke (90mm) — and pistons — as the 350cc single.

The Super Meteor followed in 1955 as a more sporting Meteor. Made in response to U.S. market demands for more power, it made 40 horsepower and was the first Royal Enfield capable of 100mph. The 51 horsepower Constellation followed in 1958 with hotter cams, a single 10TT9 Amal carb and siamesed exhaust.

In 1961, the factory made a limited run of Constellationbased specials for the U.S. market, the 700 Interceptor. Set up

for offroad enduro-style events, they weren’t popular and most of the approximately 160 bikes were retrofitted by dealers with aftermarket horns, mirrors and lights and sold for road use.

In late 1962, Royal Enfield bored and stroked the Constellation’s engine to 736cc to launch the 750 Interceptor Mk1. It went head-to-head in the showrooms with the new Norton Atlas 750 and, like the Norton, it was aimed squarely at the U.S. market. Both bikes were offered stateside before they became available in the U.K.

Enfield dynamically balanced its big twin engines, reducing vibration compared to large displacement bikes made by competitors, who used static balancing. The long-stroke design produced abundant torque from low revs, making the bikes very tractable and capable of impressive acceleration. On the downside, the separate barrels and heads meant that the engines — being stressed members — tended to flex, which, combined with poor crankcase venting, led to the bikes having a reputation for leaking oil, hence the nickname “Royal Oilfield.”

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 37

1963 ROYAL ENFIELD MK1 INTERCEPTOR

The Interceptor was upgraded in 1964 with a second petcock, float bowls on both Amal Monoblocs, magnetic instruments, Girling shocks, an auto-advance magneto, hotter “R” (Supersport) cams, and one less tooth on the countershaft sprocket for better acceleration. In the U.S., the 1964 model was known as the TT Interceptor. The single-carb Custom with standard cams was added in 1965, and the 1966 GT with twin carbs and sport cams gave three Mk1 models available that year.

The Interceptor Mk1a was introduced in late 1966. Produced at new facilities at Bradford-on-Avon, it featured twin Amal

concentric carbs, coil ignition and better engine breathing. Two models differing only in cosmetics were offered in the U.S.: the Road Scrambler TT7 (upswept pipes, chrome tank and exposed chrome shock springs) and the Road Racer GP7 (flat pipes, painted tank and shrouded shocks, more like the old Mk1).

Royal Enfield produced its last twin, the Interceptor Mk2 (aka Series 2), from 1968 to 1970. The engine was redesigned to be wet-sump, the contact points were relocated in the timing cover, and Norton front forks and front brake were used. The Mk2 bikes

leaked less oil than the Mk1 versions, but were heavier and slower. The factory had plans for an 800cc Interceptor Mk3 successor, but never put it into production, although prototypes were made and road tested.

The Royal Enfield Interceptor was considered one of the Superbikes of the Sixties. When a Mk1 ran a 13.8-second quartermile, Cycle World editors proclaimed it the quickest stock production bike they had ever tested. In addition, a bike powered by two Royal Enfield Interceptor engines was the first non-streamlined motorcycle to exceed 200mph, hitting 203.16 mph at Bonneville in 1970.

Greg’s Interceptor

Greg Lawless’ 1963 Mk1 Interceptor was one of approximately 250 built that year and one of 979 Mk1s produced between 1962 and 1966. There were two variants of the Mk1 for the U.S. market — Greg’s is the second type with a polished alloy instrument nacelle (not black) and a polished alloy wing knob for the steering damper (rather than a big black round knob). Unlike the U.S. models, the Mk1s sold in the U.K. and the rest of the world had bigger gas tanks, twin-sided 6-inch front brakes and shorter swingarms and wheelbase.

The 1962-1963 Mk1 had twin 1-1/8-inch Amal Monoblocs sharing one float bowl, a Lucas K2F

manual-advance magneto, a 6-volt alternator and a 4-speed Albion gearbox with a neutral finder. The gas tank had a single petcock (there was no reserve), and a Smiths chronometric speedometer and tachometer were standard.