9 minute read

SAIL FOR EDUCATION

EQUITY IN ACTION:

Advertisement

A GLIMPSE INSIDE ONE TEACHER’S CLASSROOM

REBECCA HORNBERGER, PhD Department Chair, SAIL for Education

It’s a familiar scene that plays out in classrooms throughout our schools on a daily basis. A teacher is working with a small group of students, and a line starts to build to her side. A little girl, Katie, notices that her classmate, Jacob, is standing in the line with a writing piece that he has painstakingly completed. However, this is not a typical classroom, and the leader of this classroom is anything but average. Because Katie is part of this unique learning environment, she knows exactly why her classmate is standing in line, and she knows what he needs to move forward in his work. She turns toward Jacob and comments, “I see you worked very hard on your writing, Jacob. This is good work—I’m very proud of you.” He nods in agreement and returns to his seat to continue with his independent work. I had the privilege of witnessing this interaction in a classroom run by Mrs. Marybeth Johann, a seasoned educator who taught first grade in the school where I served as principal. This is just one of the many examples of the extraordinary learning environment that Mrs. Johann created within her classroom on a daily basis. You might be asking—what does Mrs. Johann’s teaching and professional practices have to do with educational equity? The answer is simple: within my school building, the teacher who best exemplified equitable practices in everything she did was Mrs. Johann. And I firmly believe that, as principals, we must be able to recognize the types of equitable practices that will have the greatest impact on student learning. Our recognition is the only way to move beyond merely providing equal opportunity and instead pushing toward assuring that barriers are systematically removed so that every student’s full potential is realized. We must understand what equity looks like in practice so that we hold ourselves, our teachers, and our entire school community accountable in assuring equity across all facets of our educational systems.

The Center for Public Education (2016) “set forth the areas in an equity agenda that research shows will have the greatest impact on student outcomes.” Those areas include teachers, curriculum, discipline policies, and funding. This is essential because educational equity is “more than a guarantee that the school doors will be open to every child.” Equity in today’s schools is about assuring that students have received all the tools needed in order to ensure their success in the future. Within the areas of teaching and curriculum, clarity is essential in identifying the key teacher qualities and curricular practices that will have a positive impact on student outcomes. Darling-Hammond (2013) explained that teacher quality is the personal characteristic that an educator brings to the teaching profession. Research has shown that the following teacher qualities have a positive impact on teacher effectiveness: a strong content knowledge of the subject area to be taught, as well as a knowledge of how to teach the content to others; an understanding of how to support diverse learners in their academic growth; the ability to make EQUITY

observations and both organize and explain ideas; and expertise in adapting and modifying curriculum and instruction based on student needs (Darling-Hammond, 2013).

Darling-Hammond (2013) expanded on this idea by explaining that many parents, policy makers, and educators would add the following characteristics to these essential teacher qualities:

• support learning for all students; • teach in a fair, unbiased manner; • adapt instruction to help students succeed; • strive to continue to learn and improve; and • collaborate with other professionals and parents in the service of individual students and the school as a whole. (Darling-Hammond, 2013, p. 11)

Mrs. Johann’s classroom was a model of effective curricular practices coupled with exceptional pedagogical skills. To support diverse learners, she practiced true differentiation on a daily basis—it was deeply embedded in her daily classroom practices. For example, students were intentionally grouped in both math and reading based on pre-assessment data. These groups were flexible and changed based on skill acquisition. At the individual level, she also provided work that was based on each student’s needs, much like the individualized work plans that are used in many Montessori classrooms.

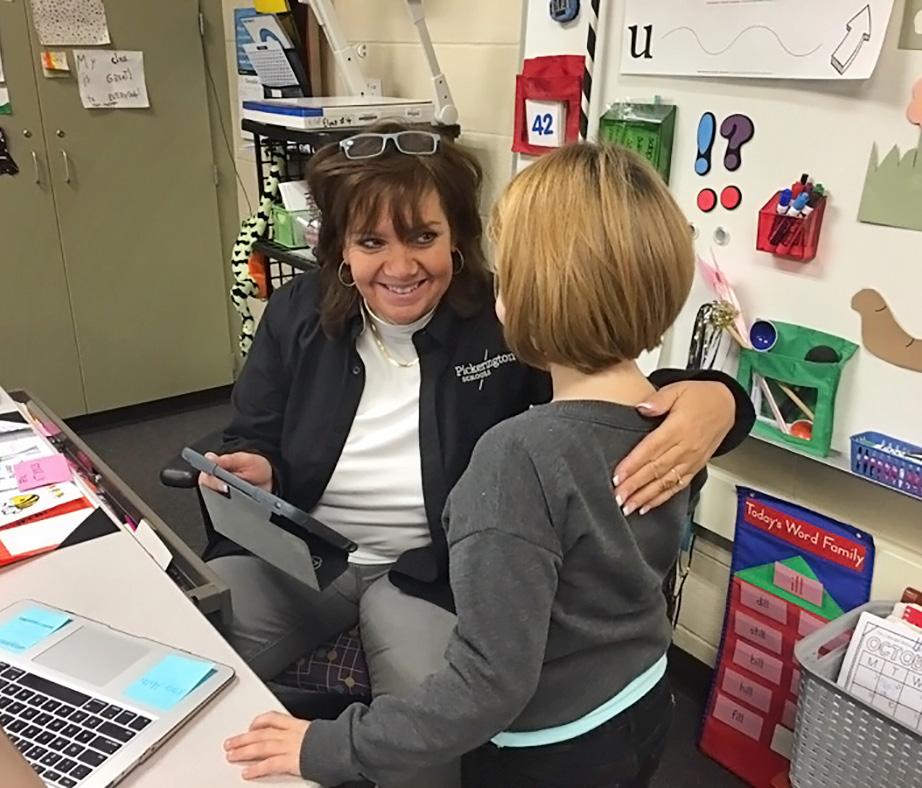

Mrs. Johann also used teaching strategies that empowered students with their own learning. From the first minute that her young learners entered her classroom at the beginning of the year, they were enveloped in an environment that assured that learn

Mrs. Johann and one of her students

The “I” Corner

ing would take place. In her room, getting overlooked simply wasn’t an option—every interaction with her students communicated their importance, both as learners and as people. Her unconditional love and acceptance also came with the expectation that an attitude of perseverance was essential, and every single student rose to meet this call.

The next essential area of focus in an equity agenda is student discipline. The Schott Foundation for Public Education (2017) made the following statement about the transformation that is starting to take place across the nation when it comes to positive school climates and equitable disciplinary policies: “Increasingly, schools are moving away from harmful and counterproductive zero-tolerance discipline policies and toward proven restorative approaches to addressing conflict in schools. Everyone thrives when a school community is a healthy living and learning climate for all.”

What does a healthy learning environment with effective disciplinary procedures look like from the practitioner’s point of view? In my mind, it looks very much like the interaction I witnessed between Katie and Jacob in Mrs. Johann’s classroom. In this situation, both students were keenly aware of multiple classroom expectations and “ways of doing business.” They were empowered with the ability to monitor themselves and one another because the classroom was a true community in which all members took care of one another and themselves.

Katie had obviously observed how the “lead learner” (Mrs. Johann) used positive reinforcement to support student learning. Katie also felt empowered with the ability to support others in their learning and did so through her verbal exchange with Jacob. Further, Jacob understood that approval and reinforcement did not have to come exclusively from the teacher. He valued his classmates to provide needed feedback and reassurance so that he could continue his work.

Another example of Mrs. Johann’s student-centered disciplinary procedures was her “I” corner. Students used this corner to talk out problems or issues that arose on the playground or in the classroom. Mrs. Johann was intentional in teaching students specifically how to use the “I” corner appropriately. It was modeled and practiced repeatedly at the beginning of the year before the corner was opened for community use. For the remainder of the year, students used this space to work out issues and problems as they arose. The benefits of the “I” corner were substantial because the learning process in the classroom continued without interruption while students also learned how to handle conflict in an appropriate and mutually beneficial way.

In contrast to the adult in the room always doling out reinforcement and/or correction, Mrs. Johann’s students had been intentionally taught that they could provide what is needed to each other. Her classroom did not belong to the teacher; rather, it belonged to the students and they took up the mantle of that responsibility willingly. Most importantly, this willingness to share ownership of the classroom made Mrs. Johann’s students feel valued and important, and those feelings, when deeply engendered and internalized within students, dramatically reduce or even eliminate misbehavior.

The fourth area of focus to ensure equitable practices is funding. As principals, we often feel that funding is outside of our locus of control. However, we must be aware of the disparities in funding across our public schools, and we must commit to level the playing field as much as possible for our students and schools.

lars. Combined, they support about 90 percent of the total budget. How these dollars are distributed within states can manifest in sizable revenue gaps between districts based on the poverty rates of the students they serve.”

Yet, principals and teachers must work within their fiscal limitations to assure that a lack of funding is never a barrier to student learning. Mrs. Johann taught me how to remove the funding barrier. After attending an intensive phonics training one summer, she immediately hurried over to my office and let me know we were doing our students a disservice and we must rectify the situation immediately.

She further explained that our phonics instruction was inadequate, piecemeal, and inappropriate for students. They were receiving one type of instruction in preschool, another method in kindergarten, and yet another in first grade. She was blowing the whistle on these ineffective practices and said that she was willing to do whatever it might take to align ourselves across grade levels and commit to a systematic, sequential, and research-based phonics program.

However, our building funds for the year had already been fully allocated and there was no money left to devote to this curricular initiative. Mrs. Johann did not let this lack of funding stop her from providing for our students. She solicited local businesses and worked closely with our PTO to raise more than $6,000 to implement effective phonics instruction for preschool through second grade.

learner at our school. In an educational environment in which many factors feel beyond our control, educators such as Mrs. Johann remind us that we do, in fact, have the ability to significantly influence our students and their learning.

As we continue to address the essential aspects of equity in education, we must embrace every opportunity to transform our classrooms and our schools. It is a moral imperative that lies at the core of our responsibility as educators. John Dewey’s (1915) words continue to ring true today: “What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all of its children…All that society has accomplished for itself is put, through the agency of the school, at the disposal of its future members.”

References

Center for Public Education. (2016). Educational equity: What does it mean? How do we know when we reach it? Retrieved from http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/educationalequity

Darling-Hammond, L. (2013). Getting teacher evaluation right: What really matters for effectiveness and improvement. New York, NY: Teacher College Press.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017) An equity Q&A with Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond. Retrieved from http://www.hunt-institute.org/resources/2017/09/an-equity-qa-with-dr-linda-darling-hammond/

Dewey, J. (1907). The School and Social Progress. Chapter 1 in The School and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 19–44. The Schott Foundation for Public Education. (2017). Retrieved from http://schottfoundation.org/issues/school-climate-discipline

in partnership with

Continuing your education? Check out our programs: EDUCATION LEADERSHIP -Principal Licensure: MA | Licensure | PhD/EdD -Teacher Leader: MA | Endorsement | PhD/EdD -Superintendent: Licensure | PhD/EdD ADDITIONAL PROGRAMS -Reading: MA Specialist | Endorsement -Differentiated Instruction: MA -Online Teaching for pre-k–12 Educators: MA -Teaching and Learning: MEd PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS -Simple, streamlined application process -Up to 50% transfer credits considered -Up to 34% tuition discount for MA programs -Loan forgiveness—up to $5,000—may apply

Get started today! Contact us by e-mail at info@sailforeducation.org or by phone at 888.964.SAIL.