8 minute read

Why Did You Do That?

BY PAUL G. YOUNG, PH.D. OAESA PROFESSIONAL CONFERENCE PRESENTER

When I was a young boy and did something my parents would question, they’d often ask, “Why did you do that?” Sometimes, I didn’t know. Other times, I did. I wasn’t always a good kid. I tested limits. Along the way I realized there was much to learn as I figured out the mysteries of life.

Advertisement

It never occurred to me then how much value judgement was embedded in the “Why did you do that?” question. Everything I did, or did not do, reflected some assessment of my parents’ (and others’) differentiated standards for my behavior and expected accomplishments. I learned that whatever I did, and why I did it, could be done better or worse. The voice inside my head taught me that to do things better, to be different than other kids, to attain quality according to my loved ones’ standards, required making choices and putting forth effort that would gradually make me better.

SO, WHY DID I BECOME A TEACHER?

I wanted to be just like the music teachers I’d loved during school. I sought for myself the respect, wisdom, and the prestige I’d witnessed them attain. I was probably too young to completely grasp everything it meant to become a professional, but I did know that I enjoyed emulating them and sharing my passion for music with others. Over the years, I’ve never lost the desire to teach, but I gradually realized it wasn’t enough.

SO, WHY DID I BECOME A PRINCIPAL?

I wanted to be better. A decade ago, Simon Sinek published Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. A subsequent TED Talk has become the third most-watched TED video of all time. His work explains how leaders with the greatest influence think, act, and communicate differently than others. The release of the book started a movement that has helped people become more inspired at work by focusing on choices, purpose, and effort. He described the search for the “why” as what drives us to do what we do—better.

I’m sure you’ve been asked the question “Why did you become a principal?” I was, and I often struggled to give a good answer. I know many aspiring and practicing principals similarly grapple with the same question. Even as a retiree, Sinek’s work has helped me focus, but still, common responses that I hear today seem to reflect ideas, perhaps somewhat cliché, such as:

• I want to do good things for people. • I have a vision that I want to bring to life. • I want to turn kids on to learning and reading.

I’m not convinced that these types of responses are as sufficient, descriptive, or remarkable as they could be.

Explaining why you chose to become a principal is hard to do. To me, an effective response reveals common sense and modesty wrapped with a strong desire to be more than mediocre. Principals must inspire children and adults to become better today than they were yesterday. Principals must commit to continuous self-growth and making schools better tomorrow than they are today. Of all the common responses heard about reasons to become a principal, we seem to focus very little about how the job allows us to make magic.

WHAT IS THE MAGIC? Thousands of years ago, magicians were advisors to kings and queens. They made illusions seem like reality. They still do. Artistically different from musicians who produce masterful sounds with a series of pitches, or painters who create visual displays with basic colors, magicians combine a potpourri of effects to create their mystifying illusions. Similarly, principals merge instinctive influences in their work that make magic. Those effects include: •Appearance: thousands of skills and strategies that make things look big, small, good, or bad •Disappearance: tricks of the hand that make problems and challenges seem to vanish •Presence: bearings of authority, confidence, commitment, and competence •Levity: capacities which can defy the downward pull of deeprooted challenges •Production: understandings of how professional attire, staging, lighting, directions, theatrics, and storytelling combine to influence daily performances •Penetration: abilities that drill deep and gain insights that others cannot •Transposition: initiatives that move ideas from point A to point B •Transformation: practices that convert problems into something else, something better •Perception: gifts for envisioning a better future •Restoration: sensitivities that rebuild those who hurt and make them whole again Magicians aren’t born as magicians. Neither are we born as principals. Both professions require years of training, determination, and persistence to perfect a craft. To observers, principals’ good performance is pure mystery. And when it is really good, it brings smiles and great satisfaction to children and adults—and us! Differentiated Standards of Accomplishment Not only did I understand the studying that would be necessary to fulfill licensing requirements to become a principal, I realized I needed continuous practice in being a good person. I recognized that I wouldn’t know why I had to do what I needed to do as a principal if I didn’t simultaneously develop social, emotional, and spiritual strength. I made time to read, collaborate, study, learn, and strengthen my personal and professional values. I believed that I might become an accomplished principal by advocating the best interests of kids, but I realized I’d ultimately fail as a person (as well as a principal) if I flopped at being a good husband, father, brother, son, neighbor, and friend to those around me. Principals will never be equal in our abilities or the professional outcomes we achieve. The specifics unique to each of our positions are such that many comparisons are simply inappropriate. The knowledge and skills needed to lead urban schools differ from what is needed in suburban and rural areas. But what is similar, and a common standard for what we must know and do, is sharing the magical purpose of our positions and developing greatness, together. This professional association played a critical role in developing the standards for my performance as well as my colleagues. Both OAESA and NAESP facilitated intentional gatherings, developed and elevated our professional dialogues, and supported and advocated for our interests. I am grateful for those who served before and with me and, by example, showed me how to create the magic of being a principal. Those mentors were generous of their time and knowledge. But when I’d ask them the “Why did you do that?” question pertaining to the principalship, most couldn’t answer with great specificity. They just knew that what they did was often very instinctive. Instinct is a critical part of the mysterious magic of why we do what we do. Magicians aren’t born as magicians. Neither are we born as principals. Both professions require years of training, determination, and persistence to perfect a craft.

When I decided to become a principal, I recognized that my work would be evaluated as better or worse than my peers. I realized the job came with a chance of success or failure. Yet, I assuredly knew it was worth doing—for kids, for teachers, for parents, for my community, for my family, and for me. I genuinely wanted to help people, but more, I sought opportunities to make magic. To do that, I knew I needed to practice. Recommended Reading

National Association of Elementary School Principals, (2007). Leading Learning Communities: Standards for What Principals Should Know and Be Able to Do. Alexandria, VA: NAESP. Sinek, S. (2009) Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to

Sinek, S., Mead, D. & Docker, P. (2017). Find Your Why: A Practical Guide for Discovering Purpose for You and Your Team. New York: Portfolio/ Penguin.

Peterson, J. (2018). 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Toronto: Random House of Canada.

Young, Paul (2004). You Have to Go to School - You′re the Principal! - 101 Tips to Make It Better for Your Students, Your Staff, and Yourself. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Dr. Paul G. Young, a past-president of OAESA, also served as President of both the National Association of Elementary School Principals (NAESP) and the National AfterSchool Association (NAA). He most recently retired as an adjunct professor of music and education classes at Ohio UniversityLancaster. He has written extensively on topics of school leadership, school and afterschool alignment, teacher preparation, and more. His books for principals and afterschool professionals can be found on Amazon.com. He has led training workshops throughout the country for school and afterschool leaders. He can be contacted via email at paulyoungohio@gmail.com or via Twitter at @ paulyoungohio. He will be presenting “Why or Why Not? 5 Whys of Principal Determination” as a clinic topic at the 62nd Annual Professional Conference and Trade Show on Thursday, June 13, at 12:45–1:30pm. LEADING INNOVATION FOR TODAY’S LEARNERS LEADING INNOVATION FOR TODAY’S LEARNERS

JUNE 5-6, 2019

CENTRE PARK OF WEST CHESTER 5800 MULHAUSER RD WEST CHESTER, OH 45069 CENTRE PARK OF WEST CHESTER 5800 MULHAUSER RD WEST CHESTER, OH 45069

LEARN MORE & REGISTER AT WWW.HCESC.ORG/NAVIGATOR

1. Download the app and create your conference schedule.

GET THE APP!

Get the free conference app today to create your custom clinic schedule, learn about the presenters, meet other attendees, and more.

CONNECT TO OAESA’S ANNUAL

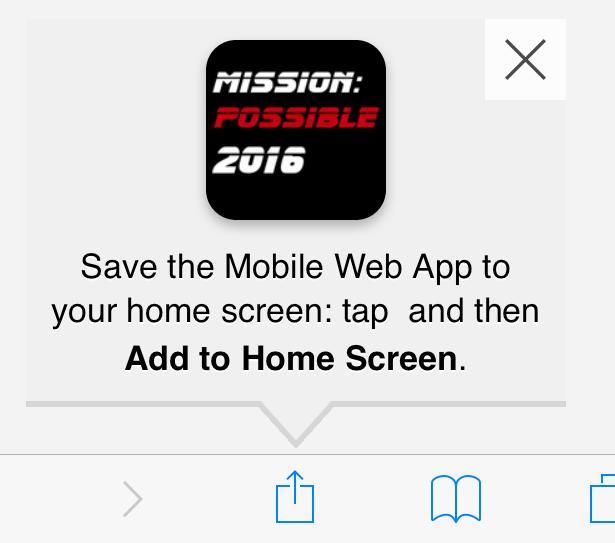

1. Visit OAESAMagic2019.sched.com on your mobile device.

2. Add the shortcut to your home screen— no download required!

PROFESSIONAL CONFERENCE

Webinar: RSVP at oaesa.org April 26, 9:30–10:30 AM Hacking Leadership with Dr. Joe Sanfelippo 2. Attend no-cost PD online prior to the conference.

Twitter Chats follow along with #ohprinchat May 7 at 8:00 PM Avoid Summer Slide (for Kids & Adults!)