ANAK NUSANTARA

ISSUE 01: Imbang

EDITED BY:

AURELLI LAZUARDI

DESIGNED BY:

AURELLI LAZUARDI

WRITERS:

AURELLI LAZUARDI

TETA ALIM

TRANSLATOR:

TETA ALIM

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS:

FAJRI AZHARI

GREGO GERY

KHAIRI SETIAWAN

CONTRIBUTORS:

YOSSEP AFFANDI

GILANG KURNIAWAN

ELBIE FAJORRY

WWW.ANAKNUSANTARA.COM

@ANAK.NUSANTARA_ZINE

002 RAIN & FEELINGS

@2024

ANAK NUSANTARA

AN HOMAGE TO THE RESILIENT SOULS WHO TURNED TURMOIL INTO TRIUMPH AMIDST INDONESIA’S HISTORY OF POLITICAL UNREST. THROUGH THE HAZE OF CHAOS, THEY FOUND UNITY AND PERSEVERANCE — REMINDING US THAT EVEN IN THE DARKEST OF TIMES, HOPE AND SOLIDARITY PREVAILS.

FROM EDITOR THE

During the creation of Anak Nusantara, I often found myself lost in nostalgia, reminscing about childhood afternoons spent around the kitchen table with my grandmother and her siblings. The smell of incense lingering in the air, the soft murmur of voices speaking in a langauage that felt both familiar and foreign.

At just 13 years old, I didn’t fully grasp the significance of those conversations. They were about more than just laughter and shared meals; they were a journey through a shared past. Sharing of traditional recipes, gasps and anecdotes of the past. But alongside the memories of those afternoons, there were darker moments. Voices hushed as they discussed experiences they faced during the 1947 massacre against Indonesian-Chinese citizens. Words like “rape”, “murder” and “hatred” were thrown across the table, painting a stark picture of the hardships endured by my own family members.

The dark past of the Indonesian-Chinese community was always shielded; shrouded in shame, silence and an unspoken reluctance to confront painful truths. It was a history stained with pain and injustice, intertwined with resilience and perseverance. Those childhood afternoons became a crucible of memory. Each anecdote, each reminiscence, added another layer to the narrative of our family’s history.

Reflecting back, it gave me the motivation to pursue the truth and the courage to retell stories less shared. As I delved deeper into my family’s history and the broader narrative of the Indonesian-Chinese community, I realised the importance of shedding light on the shadows of the past.

Anak Nusantara became a journey of discovery, not only for myself but for future generations who deserved to know the unvarnished truth of their heritage. It was about our sense of belonging in a world that often felt fragmented and uncertain. It was as if those conversations were stitching together the threads of our past, weaving a tapestry of who we are and where we come from.

Through the creation of our first issue, I discovered stories of struggle, and of triumph. I learned the rich tapestry of cultures that make up the fabric of Indonesia. I came to understand that our past is not just a series of events confined to history books; it is the foundation upon which our present stands. Through it all, one thing became clear: identity is not a fixed point on a map, but a fluid, ever-evolving landscape.

In embracing my heritage, I found liberation — from the constraints of categorisation, from the tyranny of labels, from the illusion of certainty. For in the vast expanse of the human experience, there are no absolutes, only shades of grey, nuances of meaning, depths of understanding.

As we confront the complexities of our past, let us do so with courage and with open hearts. Let us embrace the lessons it has to offer and let us honour the struggles of those who came before us. For it is only by understanding where we come from that we can truly know who we are.

Yours Truly,

Aurelli Lazuardi. Editor-In-Chief

Aurelli Lazuardi. Editor-In-Chief

006

IN RETROSPECT

(CHAPTER ) (01)

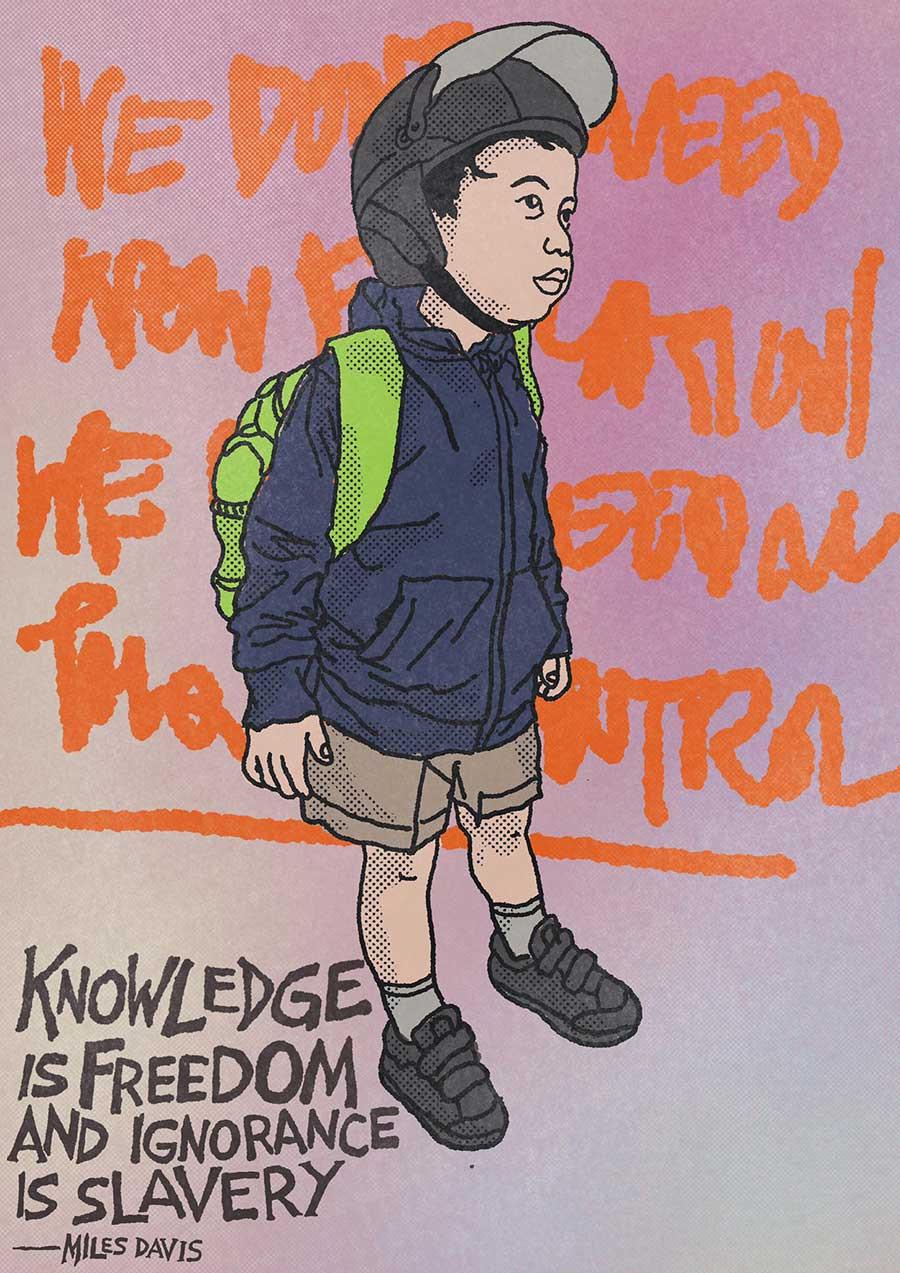

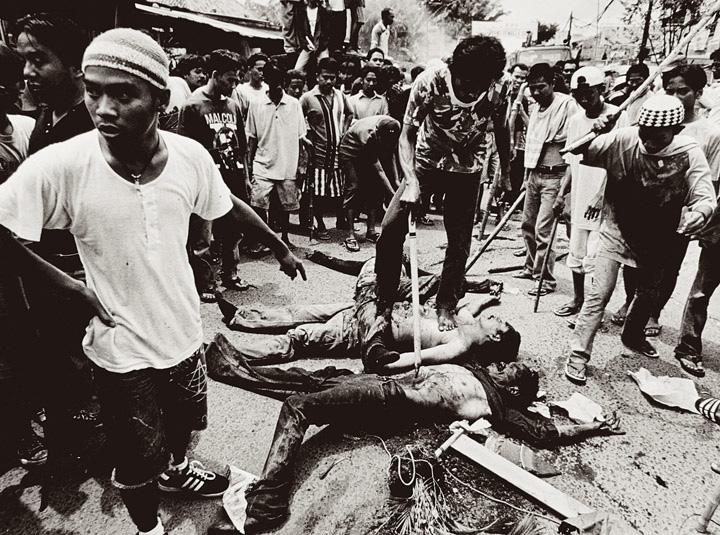

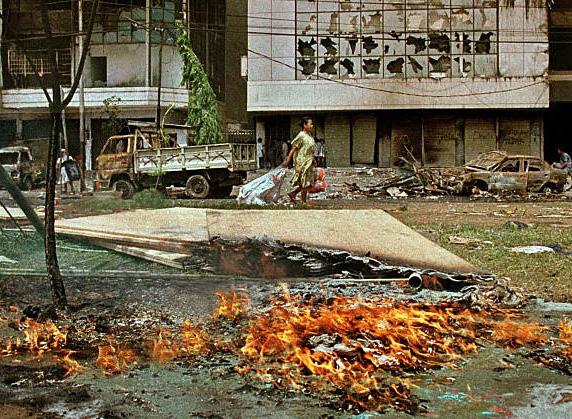

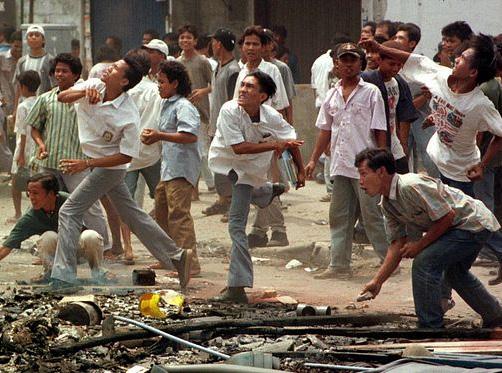

Img. 1 — Artifacts of Conflict.

Amid the chaos of the 1997 riots, everyday objects can turn into tools of conflict. Barbed wire became more than a simple fencing material—it was repurposed as a weapon, inflicting wounds that echoed the pain of a divided society. Metal wire, once a symbol of industry, was twisted into makeshift snares, trapping and injuring unsuspecting victims. Metal shards and wrenches, typically tools of construction, were wielded with malicious intent, leaving scars both physical and emotional on those caught in the crossfire. These remnants serve as haunting reminders of the violence that once tore through the fabric of our community.

007

(1)

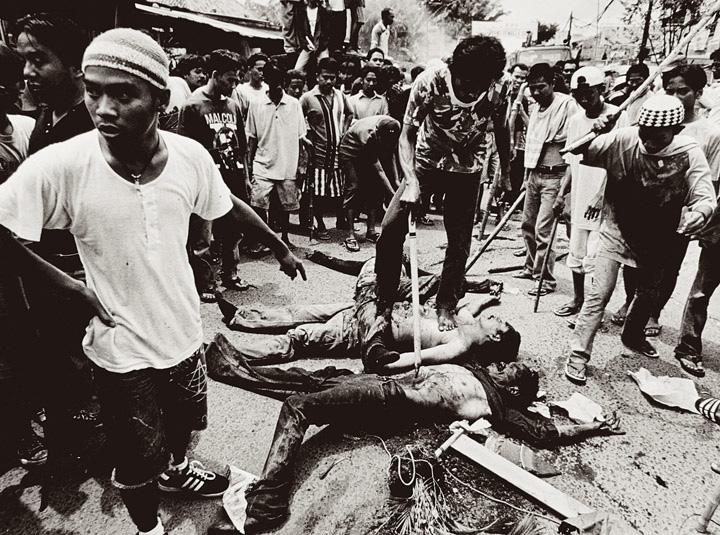

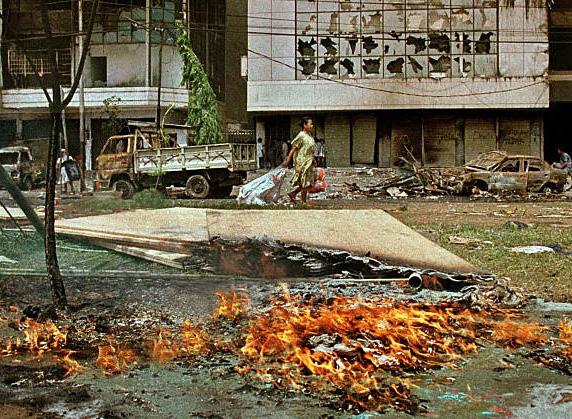

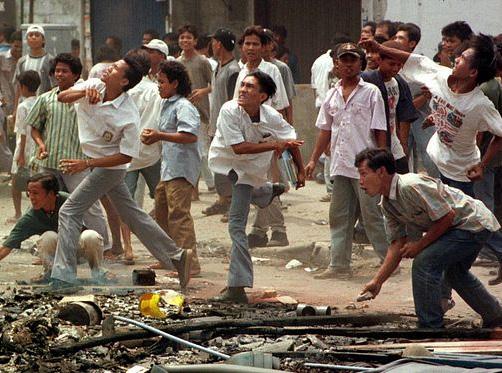

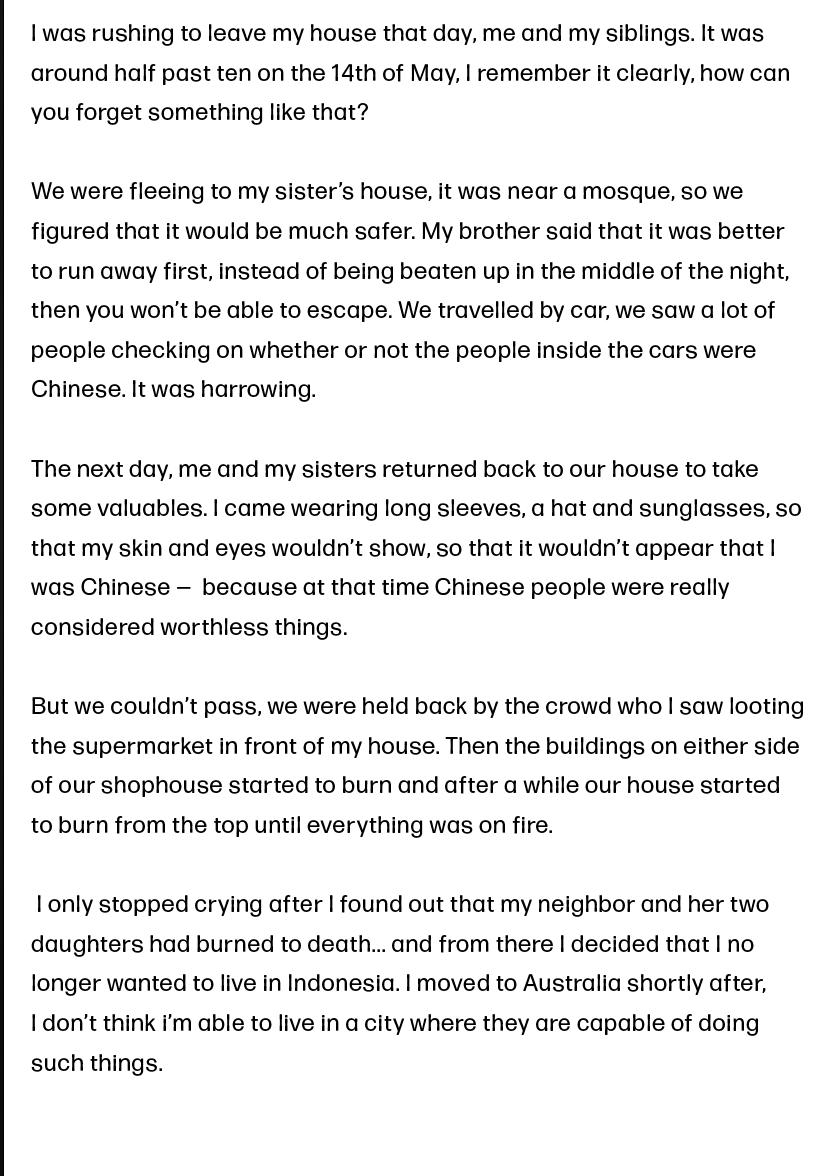

A SERIES OF PICTURES CAPTURED FROM THE MAY 1998 RIOTS, CREDITS TO KOMPAS.ID MENOLAK LUPA!

008

MENOLAK LUPA!

DO NOT FORGET!

Words by Teta Alim

I n the twilight years of his authoritarian rule, President Suharto stood at the precipice of a nation on the brink. The economic downturn that began in 1997 had shaken the foundations of Indonesia’s once booming economy, leaving behind a trail of unemployment, inflation and despair. Amidst this backdrop of economic uncertainty, along with rising political discontent, ethnic tensions began to simmer beneath the surface. The Chinese-Indonesian minority — often perceived as a symbol of economic prosperity due to their significant role in the nation’s business sector — became a target of growing resentment and scapegoating. Whispers of ulterior motives from members of the New Order Regime, led by President Suharto, began to circulate and critics alleged that the regime was exploiting the economic crisis and social unrest to consolidate power and possibly divert attention from other issues such as corruption within the government. Critics argue that the regime’s policies, characterised by favouritism towards the pribumi (indigenous Indonesians) and neglect of the Chinese-Indonesian minority, contributed to the socio-economic disparities that fueled the violence. False allegations of economic exploitation and cultural imposition were spread, intensifying ethnic divisions and creating an environment ripe for social unrest. Adding fuel to the fire, nationalist factions and anti-Chinese organisations seized upon the unrest to propagate their agendas. They distributed inflammatory propaganda and engaged in acts of intimidation against the Chinese-Indonesian community, creating an atmosphere of fear and distrust. This toxic mix of economic hardship and political manoeuvring set the stage for the tragic events that would unfold in May 1998.

The catalyst for the riots started on May 12 during a protest consisting of students from Trisakti University. Demanding greater transparency, accountability and democratic reforms, they took to the streets to address the systemic issues plaguing the country. They viewed the government’s economic mismanagement and alleged corruption as contributing factors to the economic downturn and social inequality that was affecting the lives of ordinary Indonesians. The heavy-handed response by the security forces to the peaceful protests resulted in a tragic escalation. Four students from the university were killed in the violent crackdown, their deaths igniting widespread anger and turning the demonstrations into broader riots that spread across Indonesia.

009

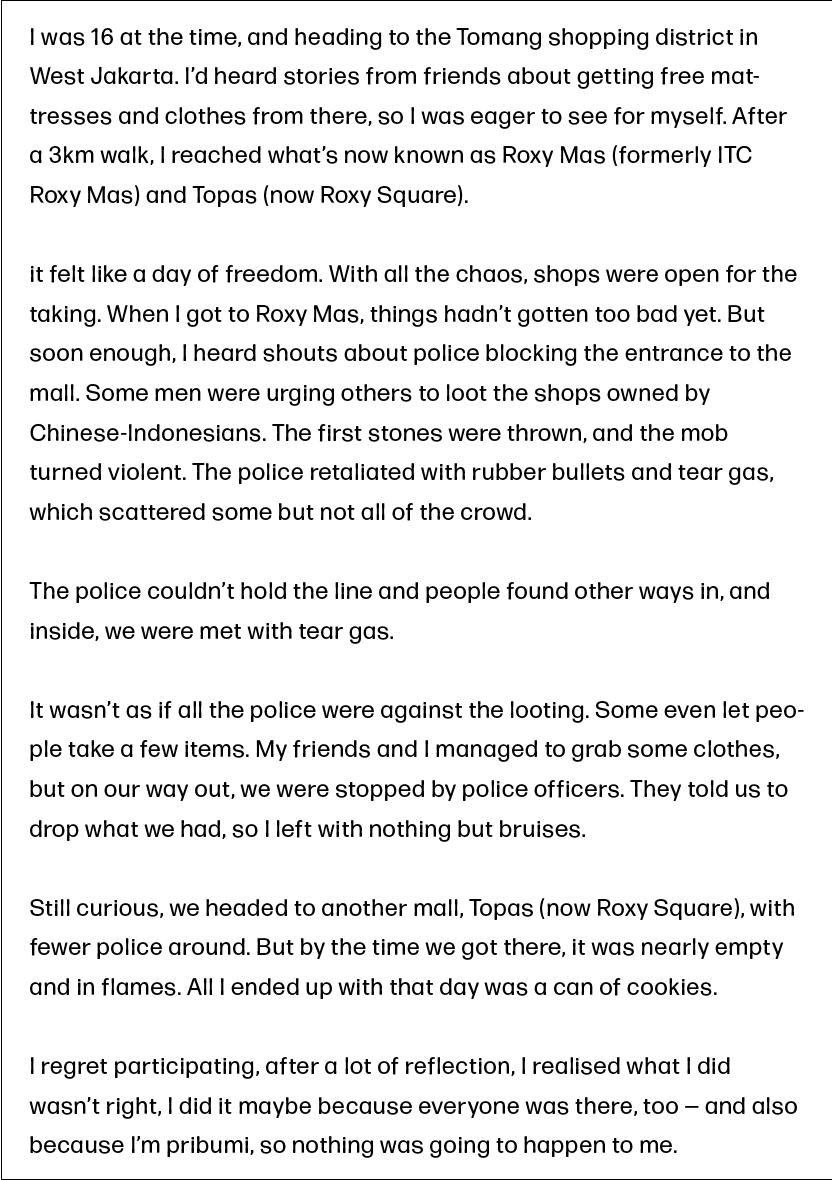

The May 1998 Indonesian riots saw a recorded 1,308 victims. 1,190 people dying from weapons. 564 people burnt alive. 91 people injured. 189 women raped, 50 of who died.

32 malls. 218 shops. 155 banks. 165 shophouses. 81 offices. 4 hotels. 38 houses, 2 gas stations destroyed and looted.

010

In Jakarta, chaos engulfed the city as mobs roamed the streets, targeting Chinese-Indonesian neighbourhoods, businesses, and cultural landmarks. Mobs specifically targeted them, hurling rocks, wielding weapons, and screaming hateful slogans. Businesses owned by Chinese-Indonesians faced the brunt of the violence. Shops were not only looted but deliberately destroyed, with equipment and inventory either stolen or vandalized.

The economic backbone of many families was shattered in a matter of hours, leaving them not only fearful but also economically devastated. Homes were invaded, with families inside subjected to horrifying ordeals. Personal belongings were stolen, and properties were ransacked, leaving homes in disarray.

The emotional toll was profound. Beyond the immediate physical and economical losses, the community grappled with a profound sense of betrayal and isolation. The social fabric that once held diverse communities together were torn apart, replaced by suspicion and mistrust. The security forces struggled to maintain order, and reports emerged of their role in the violence.

Allegations of collusion between the military and anti-Chinese groups added another layer of complexity to the situation. Amidst the turmoil, the government declared a state of emergency and imposed curfews, but these measures failed to quell the unrest. As the violence escalated, international media coverage brought the crisis to the world’s attention, putting pressure on the Indonesian government to act swiftly and decisively.

The riots eventually subsided as the government declared a state of emergency and deployed military forces to restore order. The international community also exerted pressure on Indonesia to quell the violence and protect its citizens. Curfews were imposed, and law enforcement agencies were tasked with ensuring the safety of affected areas.

Despite the immediate cessation of violence, the wounds inflicted during those tumul tuous days would take much longer to heal. The scars left behind serve as a haunting reminder of the fragility of social cohesion and the importance of fostering understanding and tolerance within diverse communities.

011

PHOTOGRAPHY FAJRI AZHRI STYLING PUTRI WIRAWAN MODEL PUTRI WIRAWAN

PHOTOGRAPHY FAJRI AZHRI STYLING PUTRI WIRAWAN MODEL PUTRI WIRAWAN

MODEL PUTRI WIRAWAN

PHOTOGRAPHY FAJRI AZHRI STYLING PUTRI WIRAWAN

MODEL PUTRI WIRAWAN

PHOTOGRAPHY FAJRI AZHRI STYLING PUTRI WIRAWAN

T ainted Crimson

STYLING AURELLI LAZUARDI MODEL RINI KARTIKA MAYA SANTOSO NIA WIDJAJA DIAN PURNAMA

PHOTOGRAPHY FAJRI AZHARI

)

CURRENT (CHAPTER

(02)

This April, we stepped into PLAY DATE’S world — a conceptual store in East Kemang.

In a city where style is a language, the store transforms into a playground for youths to express themselves; becoming a space where fashion becomes intangible with the self. Its uiquely curated selection of clothes from local designers encourages both self-expression and belonging.

Name: Rizky Ardiansyah

Age: 24

Ethnicity: Chinese-Indonesian Fashion Inspiration?

Yohji Yahmamoto

How do you show your heritage through dress? I like to blend traditional Chinese fabrics like silk with aspects of modern streetwear.

How do you think fashion can bridge cultural gaps?

It gives people the opportunity to explore new things and styles from different cultures.

Describe Jakarta in a few words.

Chaotic, inspiring, heavy traffic.

Name: Nadya Halim

Age: 19

Ethnicity: Javanese Fashion Inspiration?

Peggy Hartanto

How do you show your heritage through dress?

My grandmother is a seamstress and the clothes she makes are influenced by Javanese culture, so I like wearing her pieces out.

How do you think fashion can bridge cultural gaps?

The more cultural fusion we see in fashion, the more we can understand one another.

Write a message to the youths of Jakarta... Don’t be afraid to go all out!

Name: Michael Nugroho

Age: 20

Ethnicity: Indonesian Fashion Inspiration? My friends

How do you show your heritage through dress? I wear batik a lot,

How do you think fashion can bridge cultural gaps?

Fashion is so interesting, you can connect with others just by talking about it.

Favourite memory of the city?

Every New Years Eve, me and my friends would climb up the rooftops to watch the fireworks.

As we entered PLAY DATE, it was clear that everyone there dressed with a sense of intention. Some sported unique interpretations of Indonesian attire, combining intricate batik patterns with contemporary silhouettes. Others combined graphic tees with statement jewellery. We were reminded of how powerful fashion can be as a tool for expression, who are you?

Name: Kayla Eka

Age: 17

Ethnicity: Chinese-Indonesian Fashion Inspiration?

Vivienne Westwood

How do you show your heritage through dress?

Recently i’ve been combining cheongsams with the coquette aesthetic....

How do you think fashion can bridge cultural gaps?

It’s so fun to experiment with fashion, I feel like sometimes you can’t help but mix and match from different cultures.

Write a message to the youths of Jakarta...

Come to PLAY DATE!

Name: Henry Sutedja

Age: 23

Ethnicity: Chinese-Indonesian Fashion Inspiration? Nature

How do you show your heritage through dress?

I study fashion design and right now i’m trying to create a blend of both Indonesian and Chinese culture together, I do that by pairing different fabric and patterns from both cultures.

How do you think fashion can bridge cultural gaps?

A lot of my friends show me clothes from foreign designers, I get to learn about the history and culture behind the designs.

Describe Jakarta in a few words.

A city that never sleeps.

Name: Aisha Putri

Age: 18

Ethnicity: Indonesian Fashion Inspiration?

The girls on TikTok

How do you show your heritage through dress?

I don’t usually, but I do like wearing kebayas and kaftans.

How do you think fashion can bridge cultural gaps?

I think we’re able to bond over our love of fashion and clothes. We all wear clothes!

Favourite memory of the city?

My neighbourhood in Semarang likes to hold big dinner gatherings where we would share food and hang out altogether, I always look forward to them.

PURANA

COMBINING LOCAL WISDOM WITH ARTISANSHIP.

Words by Teta Alim

In the heart of Southeast Asia, Indonesia is undergoing a mega fashion renaissance. With a rich tapestry of cultural heritage and a burgeoning youth population hungry for expression, the country’s fashion scene is experiencing a transformation.

From the creative hub of Bandung to the heartlands of Java, the designers at the forefront of this movement are calling for a change, breaking boundaries and challenging conventions. Their creations become a harmonious blend of traditional Indonesian artisanship and modern aesthetics.

Drawing on their culture and heritage for inspiration, they weave traditional motifs and unconventional techniques to create contemporary fashion pieces. Each designer bringing a unique perspective to the table and contributing to the fashion landscape

From sustainable practices to inclusive designs, homegrown brand, PURANA, is not only shaping the future of Indonesian fashion but also redefining what it means to be a designer in the global arena.

So, prepare yourself: This evolution is not just about clothes. It’s a narrative of identity, innovation and inspiration.

026

027

PURANA , SS24 SIGNATURE COLLECTION, LOOK 2. Dahlia Kimono, featuring a monochromatic illustration of Dahlia flowers, a common decorative flower found in Indonesia which symbolizes elegance, eternal love and commitment.

From the minds of Nonita Respati, PURANA was born. Meaning ‘old scripture’ in Sanskrit, PURANA was established in 2009 with the commitment to adopt local wisdom and combine them with fashionable cuts, patterns and colours. By utilising artwork made by local artisans, Nonita seamlessly marries tradition with modern design, offering accessible fashion that resonates with the Indonesian ethos.

As the Creative Director, Nonita experiments with traditional batik techniques such as hand-weaving, tie-dyeing, modern geometrical motifs, and incorporating paintings into fabric to create unique ready-to-wear pieces that reflect commitment to local artisanship.

“Our collections are presented in multifunctional, multi-style, free-size, and relaxed loose-cuts to provide flexibility for active women to be stylish comfortably.” She says, sitting relaxed in the heart of her studio, surrounded by sketchbooks, fabric samples, and mood boards that reflect the essence of her brand.

Growing up in a traditional Javanese family and raised by her entrepreneur and Javanese culture enthusiast mother, she was exposed to batik early and was inspired to pursue Indonesian heritage as her main design focus. “It’s really important to shed light on these things,” she continues.

MANY FORMS OF ART ARE LOST TO US, AS THE NEXT GENERATION, I FIND THAT IT’S MY DUTY TO KEEP SOME THE BEAUTY OF THE PAST ALIVE.

As she shares her design philosophy, it becomes clear that she is not just creating clothing; she is crafting experiences. Each piece is thoughtfully designed to empower women, allowing them to move freely and confidently through their daily lives. It’s fashion with a purpose, designed to adapt to the ever-changing demands of modern life while honoring traditional craftsmanship.

Her commitment to inclusivity is evident in every stitch and seam. By offering a range of sizes and styles, she ensures that every woman, regardless of her shape or size, can find a piece of something that makes her feel beautiful and empowered.

It’s a celebration of diversity, a nod to the belief that style knows no bounds.

028

029

Purana X Suanjaya Kencut, versatile multistyle sarong scarf.

Purana SS24. Signature Collection. Look 4. Dahlia Lounge Set. Left Right

LULU LUTFI

LABIBI

Designers Shaping Up Batik for New Generations

“We can't preserve batik if we don't properly inform the masses about its origin and how it is supposed to be made.

The values and meanings behind the majestic fabric will dwindle over time”

031 PHOTOGRAPHY KHAIRI SETIAWAN STYLING LULU LUTFI LABIBI MODEL LIZY RIAS, JONATHAN EFFENDI

Words by Aurelli Lazuardi

Words by Aurelli Lazuardi

Some reinterpret the patterns into a new mold, and others reinvent the wear-ability. No matter the method, the purpose is the same—to keep the passion for batik alive.

For Lulu and his eponymous brand, he breathes new life into this age-old craft through the use of ‘lorek’, which translates into stripes — a traditional Indonesian fabric made from cotton strands. “Lurik has always been part of my journey in designing. It has always accompanied me.” He states in an interview.

“For me, ‘batik’ embodies the traditional Javanese cloth crafted with a specific technique—drawing intricate patterns using malam (inking wax) and a canting (pen-like wax applicator),” explained Lulu. “That’s how we create our clothes.”

To make his conventionally made batik and lurik designs more appealing to the youth, Lulu — considered a contemporary fashion darling— has been known for infusing the wabi-sabi (imperfect, impermanent and incomplete aesthetics) approach into his designs, topped with raw draperies.

“As a Chinese-Indonesian designer, I understand the importance of bridging cultural narratives through fashion, it’s why I combine traditional hanfu-inspired silhouettes with Indonesian-style draping.”

Each of Lulu’s collections is also paired with poems. His 2020’s Sandang Hening Cipta (Silent Clothing) was inspired by Joko Pinurbo’s poems in Baju Bulan (Moon’s Dress), while his 2022’s Jeda Yang Ajaib (The Miraculous Pause) was inspired by a poem by Gunawan Maryanto of the same title.

“It eliminates the distance between the people who wear my designs and me,” he said. “Fashion is a story; my collection is a story. People like to read about it because they know they’re not buying mere clothing but the feelings behind it.”

In an era where fast fashion often overshadows the value of craftsmanship and heritage, Lulu Lutfi Labibi’s work serves as a refreshing reminder of the depth and richness that can be achieved when tradition meets innovation.

032 DANYJO HIYOJI. Resort 2024 Collection.

033

Right Page

Lulu Lufti Labibi. SS24. Sauh Tweed Hobo Bag

Left Page

Lulu Lufti Labibi. SS24. LEPAS SAUH Backstage

PHOTOGRAPHY

FAJRI AZHARI

STYLING AURELLI LAZUARDI

MODEL MICHELLE HALIM

Peranakan revival

035

Kita ini apa?

Sepasang bersama yang tidak pernah sama?

Atau sepasang bersama yang hanya berpura-pura?

Kita ini apa?

Dua insan yanng saling mecinta? Atau hanya terlalu lama terbiasa?

Kita ini sedang apa?

Sama sama berjuang untuk bersama atau, Sedang berlomba-lomba menabur duka?

Kita ini mencari apa?

Kesempurnaan? Atau, mecari-cari kekurangan untuk disalahkan?

Lalu, aku ini siapa?

Atau aku ini apa untukmu?

Tiap kali kau berduka kau datang, tiap kali kau taku sendiri kau datang lagi..

Kita ini...

Mungkin kata-kata memang sudah kehilangan maknanya

036

@yossepaffandi

(CHAPTER ) (03)

037

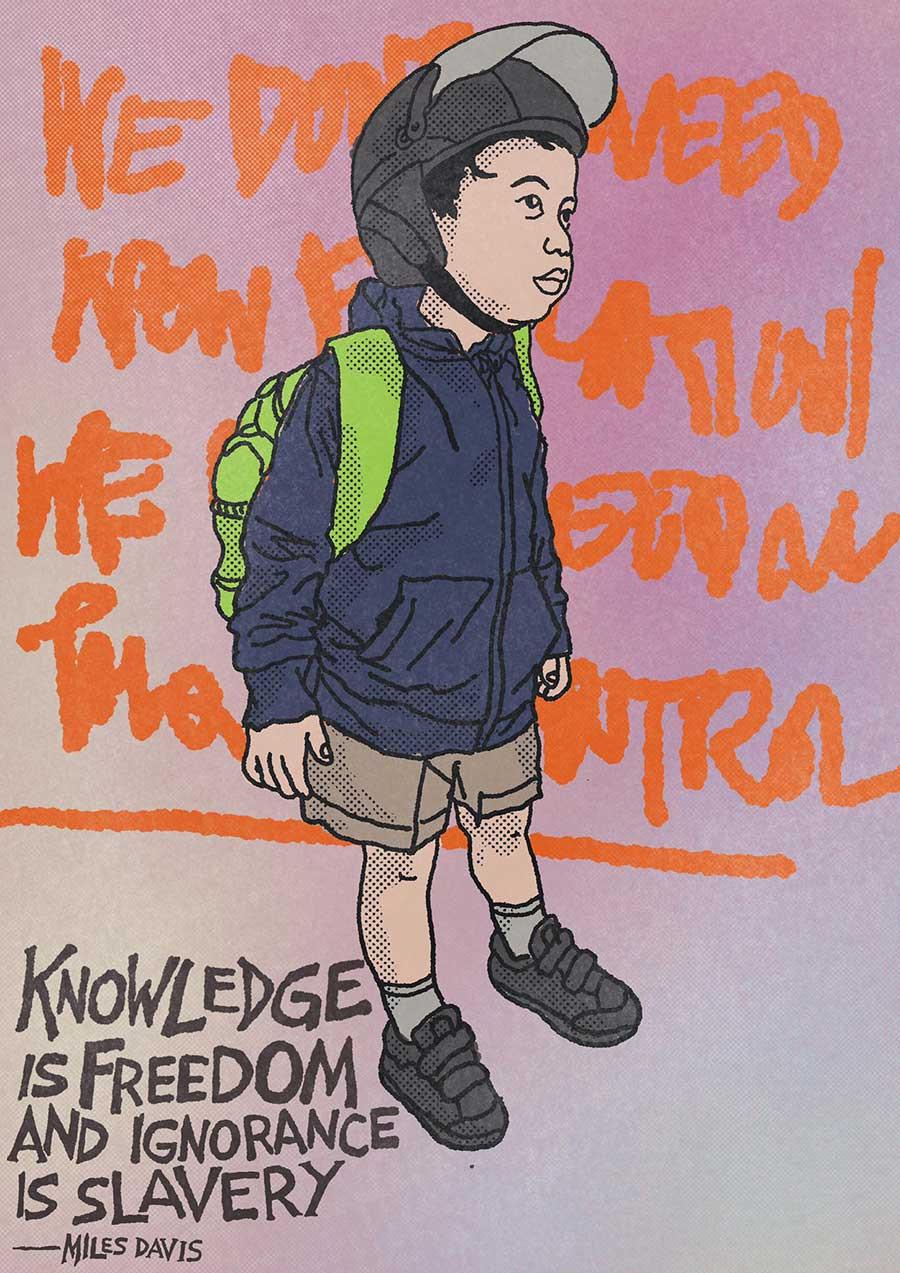

THE REVOLUTION

GILANG PROPAGILA

PRODUCTS OF PROTEST?

Words by Aurelli Lazuardi

With its rowdy solidarity, punk is the perfect genre for airing political grievances. Similarly, the origins of zines share roots with grassroots activism and communication in the underground. Combine the two together and you get Gilang Propagila.

Born from the fervent energy of Bali’s punk scene, Gilang Propagila is more than just a publishing house. Acting as a safe space for local artists to express themselves, the zines they produce serve as powerful tools of resistance. Through a blend of evocative graphic design and contributions from artists across the archipelago, they’re able to challenge the status quo.

“We know that not all types of information can be found in mainstream magazines,” Gilang states in an interview, “They have their own content direction and editorial politics. Some topics may be too sensitive or even subversive for them, some expressions may not be in accordance with the moral standards of certain parties.”

For their third issue, Gilang Propagila addresses the 1965 and 1998 riots, their release caused controversy across the island, with some saying that the topic was too abrasive. But Gilang persisted. “Sometimes people are afraid to express their opinions on sensitive matters, they are often scared of judgement and backlash. This is why it’s important to build a community that emphasises the sharing of perspectives, a space where we are encouraged to speak the truth. We’re punks anyways, it’s in our blood to do something like this.”

039

As traditional media outlets grapple with the everchanging consumer habits, a new generation of Indonesians are taking matters into their own hands, quite literally.

“These self-published books cover everything from personal stories and art to social commentary and political critique. Seeing younger kids take interest in this kind of thing gives me hope for the future.”

In the midst of societal shifts and evolving cultural landscapes, a revelation emerges: zines, those humble self-published booklets, hold the power to ignite change. Acting as a source of knowledge for their communities, they become a home for ideas or discourses which are built and strengthened through ideological and cultural work carried out by zine makers.

The realization and implementation of work in this area has made these zine makers, whether they realize it or not, become organic intellectuals for their community .

What started out as a shared interest in the

Hardcore Punk scene turned into a movement rooted in making a difference in their community.

“It starts with us.” says Gilang.

The realization and implementation of work in this area has made these zine makers, whether they realize it or not, organic intellectuals for their community .

040

AMAH KEREN BANGET ! 奶奶,您真棒! ( GRANNY, YOU’RE SO COOL! )

042

043 PHOTOGRAPHY AURELLI LAZUARDI

BY AURELLI

EDITED

LAZUARDI

PHOTOGRAPHY

GREGO GERY STYLING

ELBIE FAJORRY

MODEL BRITANNY FLOREN, DWIKA PRADNYANA, HAQQI ZAINUL, CHELSEA ONG

DANJYO HYOJI

Men RESORT S/S24

045

clothes by DANJYO HYOJI shoes by PORTEEGOODS accessories by YOURHANDS

Women clothes by DANJYO HYOJI shoes by RAJNIK accessories by YOURHANDS

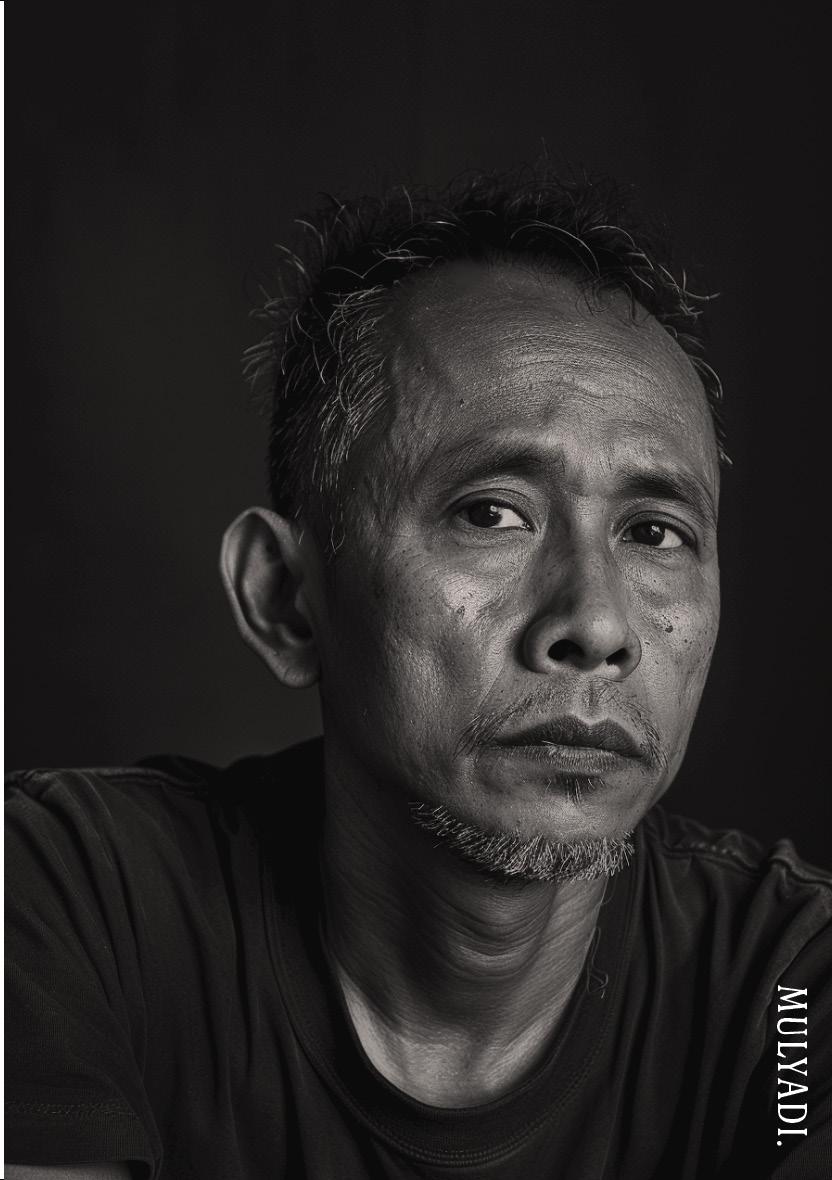

A CONVERSATION WITH EVI MARIANI

On Transparency and Serving the Underreported

Words by Aurelli Lazuardi

Evi Mariani is a known individual in her field. As the recipient of several prestigious journalism awards, Evi has pushed to cover the topics that don’t often get covered, to amplify the voices of historically marginalized communities, and reflect on how journalism can serve as a force for equity and justice. Inspired by her groundbreaking reporting on the plight of urban poor communities in Jakarta, Evi and her colleagues founded Project Multatuli in 2021 — A public service journalism initiative dedicated to carrying out the ideals of giving a voice to the voiceless, spotlighting the marginalized, and reporting on the underreported. The organization produces data-based, deeply researched news stories and collaborate with other news organizations, research bodies, and civil society groups that strive for democracy, human rights, social justice, environmental sustainability, and equal rights for all. Today, we discussed the project’s strategies to disrupt dominant practices in Indonesia’s media industry, as well as her experience during the 1998 riots and how it’s shaped her.

Aurelli Lazuardi

You’ve had a long career in journalism, from your days writing for activist student publications, to serving as a reporter and later the Managing Editor of the Jakarta Post one of the longest running and well respected newspaper in Indonesia. Can you tell us a little bit about the journey of your career and how it led you to start Project Multatuli?

Evi Mariani

It started in university, when I joined the student press. I didn’t start out as a writer, I handled the layouts, but it was during the New Order era in the Suharto regime. I remember receiving calls from the military or the intelligence officer, calling the newsrooms to stop reporting on these topics. There was no freedom of press during that era, so the student press became an alternative voice. My first brush with journalism happened when I published an issue about the 1965 communist cleansing. There was no way that the media would publish that sort of thing, and I got inspired.

After I graduated, I was like, okay, i’ll pick journalism as my life choice, and after working for The Post, I decided to start Project Multatuli with my three friends.

AL Why was it important for you to start Project Multatuli?

EM I wanted to make something different. A media outlet that really stayed true to the public. It was common practice in the Indonesia media to take moey from politically wired tycoons, or oligarchs, it wasn’t sincere. It didn’t serve the public, but more so the elites. So I wanted to disrupt that practice. Project Multatuli addresses that information inequality, we give a voice to communities that otherwise, wouldn’t have a platform, such as the LGBT community.

AL Was there a wake up call during your career? Like, what pushed you to create the project?

EM Yes. The Post has this strong standpoint about human rights, about pluralism, diversity, minonrity rights. To this day, it’s still one of the leading media outlets that talk about these issues. But when it comes to issues outside Jakarta, in remote areas, there were a lot of editors that were not warm to the idea. It’s not in our DNA to like, pay attention to, to labor rights. They lean more towards the corporate. Macroeconomics, and stories about people’s economy, like small and micro scale businesses, are not in the post DNA. When I spoke up about it, they told me that I wasn’t a journalist, that I was more like an activist, so I resigned. It was a personal battle for me, my integrities as a journalist were questioned and I doubted myself for a long time. But during the early stages of creating Project Multatuli, my friend asked me what I really wanted to do, and I told her. I wanted to serve the underreported.

046

AL I feel as though the act of calling a journalist an activist delegitimises their work. Can one maintain objectivity while also addressing structural issues and inequalities? Is it possible to sit at a “comfortable distance” and still produce relevant and impactful work?

EM I’ve observed that journalists covering sensitive issues like gender inequality and sexual abuse are often labeled as “activists” by those uncomfortable. The traditional notions of “objectivity and “balance” in journalism can be manipulated to maintain the status quo and silence marginalised voices. Instead of striving for a false balance, I think we should aim for fairness that actively addresses and tips the balance towards justice. It’s important for journalists to not only observe but actively engage in shaping narratives that address systematic inequalities and promote positive change.

AL What kind of challenges have you faced while pursuing public journalism?

EM I believe “public journalism” is actually redundant. Journalism should be for the public. However, in practice, journalism serves the powerful more than the marginalized. And when it serves the political elites and corporates more than the others, it has betrayed the public mandate. It happens because some elements of public journalism (investigation, research-based, data-based stories, in-depth, on-the-ground stories) cost money, and with the increasing power of the 1 percenter globally, journalism gets money from those who have the money: the powerful. Firewall that worked relatively well in the pre-digital era had crumbled. The question is now how can we fund good, public journalism with money that doesn’t come with interests other than for the public.

AL Where do you see digital journalism heading in the next five years?

EM We are currently at the crossroads: continuing journalism’s unhealthy relationship with big tech logic, algorithms or finding some way out of it. Many scholars, journalists, and journalism institutions, are working hard to find different ways to do journalism other than kowtowing

to SEO, algorithm, so I’m optimistic that the remaining journalists in this harsh battle brought by digital disruption would deliver some good news. Project Multatuli is actively taking part in the endeavor.

AL You mentioned that you were a student back when the 1989 riots happened, what was that like?

EM Terrifying. I’m Chinese-Indonesian, so I was subjected to a lot of racism when I was in university. I remember one time a university official in Yogyakarta asked me for my SBKRI for “administrative purposes“ only to realise that he wanted me to give him some money – it was something my non-Chinese peers did not experience. Luckily, I was overseas when the peak of the riots happened. I cannot imagine what it would be like for the people back at home.

AL Do you still feel the repercussions of the riot today?

PD Yes. Certainly. The reverberations of the riot are still felt today. While the immediate aftermath has subsided, the effects are lingering in the social fabric and political landscape. It’s not just a memory but a defining moment that has shaped the discourse and actions of various stakeholders. As a journalist, I continue to navigate its complexities, ensuring that the narratives I present are both insightful and reflective of the broader implications of that event.

AL Is there a way for individuals to contact you if they were interested in writing for Project Multatuli?

EM Yes, there is. They can pitch their idea first to Redaksi (R-E-D-A-K-S- I @Projectmultatuli.org. and pitch the idea. And then we can talk after that with the editor directly about the idea.

047

048

UspokenAggressions

049 PHOTOGRAPHY FAJRI AZHARI STYLING AURELLI LAZUARDI MODEL RINI KARTIKA MAYA SANTOSO NIA WIDJAJA

Aurelli Lazuardi. Editor-In-Chief

Aurelli Lazuardi. Editor-In-Chief

Words by Aurelli Lazuardi

Words by Aurelli Lazuardi