11 minute read

Sheb Wooley An American Cowboy in Ojai

story by MIMI WALKER

photos courtesy Suzanne Gould, Chrystie Wooley, Amelia Pate Chapman, and Old Greer County Museum & Hall of Fame, Inc.

Principally preserved is the time, and house, that Johnny Cash made a home in Casitas Springs. In the early ’60s, when Cash first came out to the valley, he had plans in motion to help bring out another crooning cowboy crony of his: Sheb Wooley, star of Rawhide and father of “The Purple People Eater.”

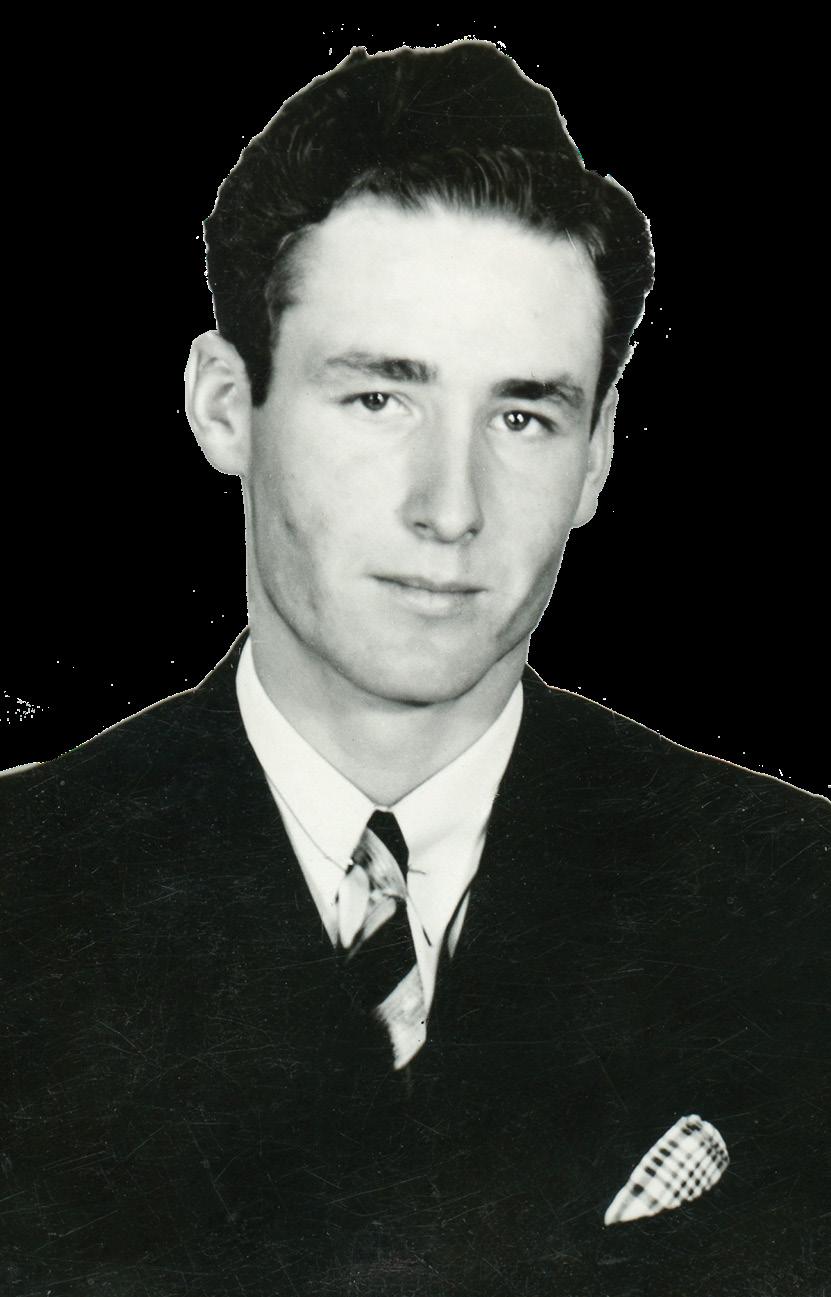

Sheb, too, began a di erent kind of legacy as he built a life around Lake Casitas — one that would impact a handful of lives in ways even more uplifting than his comedic jukebox jewels of the day. That legacy’s journey was tracked down by Suzanne Gould, a self-professed Rawhide superfan, in her book An American Cowboy: The Biography of Sheb Wooley. It begins in “The Breaks,” Wooley’s childhood turf, southeast of Erick, Oklahoma, which has a population of less than 1,000 people. It was far out into the country, the veins of the Dust Bowl; locals typically describe the area as where the “poorest of the poor lived.” Wooley’s mother, Ora, was a child bride; she was 13 when she was wed to William, his father, who was 26 at the time. Sheb was born in 1921, the fourth of five siblings. They lived hand-tomouth; the kids got one e outermost lands of the Ojai Valley experienced a distinctive cowboy era in the 1960s that is still celebrated fondly today. new pair of shoes a year. The Wooleys ventured out to Erick on Saturdays to shop and sell the cotton crop from their tiny farm patches. This is where Sheb fell in love with singing cowboy movies at the local theater, and dreamed of being a star in the same fashion. This fire in his belly urging him to break away began to kindle inside, too, on account of his “pa,” who’d come home on his mule-pulled wagon whooping and hollering from all the moonshine.

“They could hear him all through The Breaks,” Gould says. Not only did he become known to locals for rowdy drinking antics, but in Erick, William Wooley is also still remembered “to this day, over a century later, for being excessive” with the belt-beatings of his boys, notes Gould. Sheb’s eventual only No. 1 country hit, “That’s My Pa,” is a biographical account of this searing memory.

Sheb’s work ethic kicked into overdrive to get away from it all. He was always the kind of kid who knew what skills he needed to master to reach a goal. The fiddle was his father’s instrument of choice, so Sheb followed suit for a bit. By age 11, “Sheb was the kind of person who could play anything,” Gould says. “The guitar was popularized by the singing cowboys. That’s what they had, that’s what he wanted. He got his father to trade a shotgun for a neighbor’s used guitar and he taught himself how to play,” even though his father later smashed that guitar in a jealous, drunken rage.

He started o performing at age 14 at community barn dances, and a year later developed his first band, The Plainview Melody Boys. He rode his horse for hours to get to Elk City, and willed the radio station into giving him and his bandmates a weekly spot on the airwaves.

Sheb and his first wife, Melva Miller, eventually found their way to Nashville as the Grand Ole Opry was starting to take o . With massive ambitions to be a songwriter, and never without a pen and pad, he’d wait in parking lots of radio stations for bandmates of stars to come out for a smoke break, passing lyrics to them for consideration. Along the way, Sheb met Cash and they became close buddies in their musical pursuits.

In December 1945, Sheb made country music history when he recorded the first commercial record in Nashville for a Nashville label. “In that way, he really kicked o Music City,” Gould says. Things really began to change in 1946 when he relocated to Fort Worth, Texas, and was hired to be a bandleader for “Sheb Wooley and His Calumet Indians.” The band was sponsored by the Calumet Baking Powder Company and toured throughout the Southwest, appearing on several radio shows. After that gig was up, in 1949, Sheb felt he had enough fuel in the tank to go to Hollywood to try out movies. He landed several supporting roles and bit parts in notable films and TV shows throughout the ’50s, including 1951’s Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison — Cash’s inspiration for “Folsom Prison Blues” — and 1952’s High Noon, co-starring Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly, the performance that inspired Gould to write about Sheb’s life and wealth of talent lying under the surface. Sheb unwittingly cemented his status in Hollywood perpetuity as the voice behind the infamous “Wilhelm Scream,” recorded in post-production for an alligator-attack scene in 1951’s Distant Drums, another Gary Cooper film, which has now been used in several hundred films and TV shows over the last half-century.

After marrying and divorcing Miller and then Edna Talbott, Sheb met Beverly Addington at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood, and it was love at first sight for both. They wed in 1955, and a few years later adopted their only child, daughter Chrystie.

Sheb recorded and wrote music for MGM Records, but nothing charted until May 1958. When he wrote “The Purple People Eater,” it was an o -the-cu exercise in wordplay responding to the cultural “space invasion.” MGM didn’t even want to release it. But Sheb believed in the novelty ditty, and young novices playing it in the break room at work convinced execs that the song was landing with youth. It was the first single to reach No. 1 on the Billboard chart after two weeks, a record not bested until 1964 with “Can’t Buy Me Love” by The Beatles. By June 1958, Sheb made the equivalent of more than $2 million in today’s dollars.

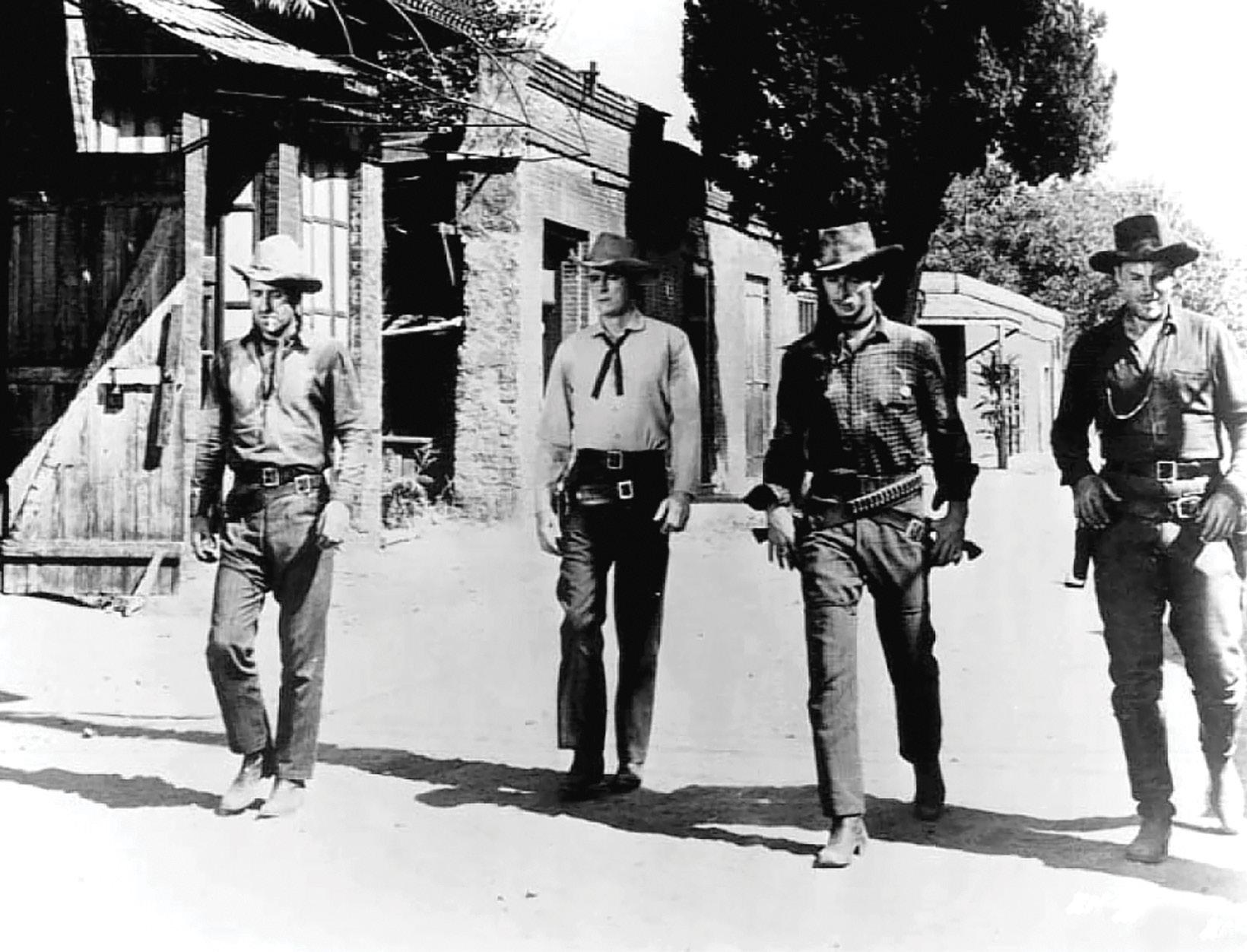

Soon after “Purple People Eater Fever” took the country by storm, as Gould coined it, the Western cattle drive adventure series Rawhide premiered on television in January 1959, and Sheb Wooley, as trail scout Pete Nolan, was the name the public recognized ahead of the tragic Eric Fleming and eventual Hollywood titan Clint Eastwood. The series was praised for its realism, and rugged-yet-wholesome appeal. Sheb stayed for a few years, but wanted to get back to the music. Always trying new things, he devised a liquored-up, comic alter ego, “Ben Colder,” in 1962 — country music’s tipsy forerunner to “Weird Al” Yankovic. For example, “Don’t Take Your Cash to Town, John” is the irreverent inverse of Cash’s ominous hit “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town.” Sheb as Colder was named Comedian of the Year by the County Music Association in 1968. He appeared many times on Hee Haw in the ’60s and ’70s; he even wrote the show’s theme song. The early ’60s was the time the Cashes and Wooleys came up to the valley from L.A. Cash oversaw construction of simple stucco duplexes in Oak View’s river bottom, which attracted a lot of folks from Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. “My dad felt really comfortable with the people that lived there,” Chrystie Wooley says. The Wooleys stayed there for six months while their property was built on Santa Ana Road, on a 26-acre plot of land 1 mile above Lake Casitas.

The Cashes and Wooleys converted a mini golf course into the Purple Wagon Square Mall of Oak View (now the Gateway Plaza); Sheb mounted an old wagon from the 1800s at the site and painted it purple.

Johnny kept his o ce there, and the wives had their own joint beauty salons: Vivian’s Beauty Spot and Bev’s Purple Wagon Beauty Salon.

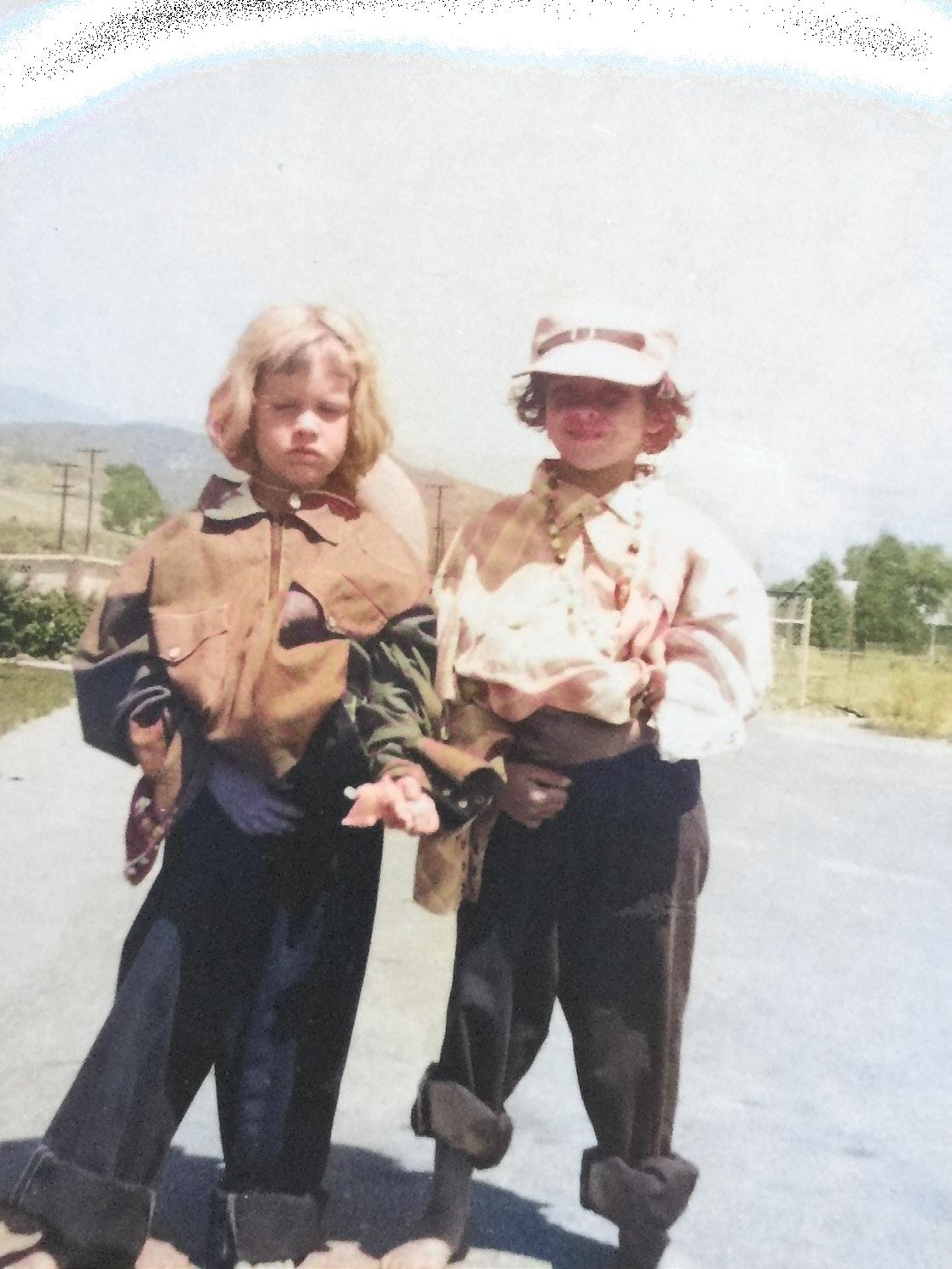

Chrystie would stay with the Cashes and their four girls when her parents had to go out of town, and she became especially close to Cindy Cash, who was the same age, running into all kinds of mischief. After Cash divorced Vivian and left the valley in 1966, Sheb took over his Boys’ Clubs of America benefit concerts.

Chrystie says growing up by the lake was “utopia.” She and her dad rode horses bareback for miles. “I knew it was special then … I had a beautiful imagination because of it.”

Her dad “loved the peacefulness … he loved spreading his wings. I knew my dad was somebody, because everyone wanted to talk to him all the time.” But, she says, “my parents were not fancy people.” Neither one was impressed by materialism; they’d happily host ordinary folks for dinner and take calls from Clint Eastwood that same evening.

When Sheb came home after a work commitment, though, his troubled childhood came back to haunt him, and he drank. “He didn’t drink the way some people drinking … get angry and hostile. My dad was not like that,” Chrystie says. In fact, he was often the life of the party; guests found him “hysterical. But he … wasn’t present,” she remembers. “I didn’t know how to really put my finger on that at the time; it just felt wrong and I’d ask him not to do it.” In the grand scheme of things, she acknowledges that his antics were comparatively “mild” against other notorious industry battlers of the bottle. Still, something had to be done. He got sober when Chrystie was 12 in the early ’70s. He came home after being away for a month, and promised he’d take her to play softball in the fields, but was too drunk the next afternoon to get out of bed. When Chrystie expressed her disappointment in his broken promise, he came quickly to his senses and knew that it was time to give it up. “I’m so sorry … I need to do something about this,” he said, and went to his first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting that very evening in Ojai.

“He did not drink at all for the rest of his life … He spent the rest of his life being available to people that he knew needed co-star and father of the electric banjo, Buck Trent, who said Sheb saved his life by bringing him to meetings; and Ventura

KUDU DJ Lee Akers, who recalled in 2015: “Had it not been for Sheb, I don’t think I would have made it another year. But here it is 46 years later, and I have nearly 32 years clean. He is directly responsible for that. … The last time I saw him … he hugged me, and said, ‘Keep after it. I love you, son.’”

By the time the ’80s rolled in, Sheb moved out of the valley after divorcing Beverly; after two decades together, she still remained “the most loyal person he had ever known and trusted her with everything,” Chrystie says. He ultimately relocated to Nashville, where he spent the remainder of his life, apart from a mid-’80s starring comeback in the sports drama Hoosiers. He passed away at age 82 in 2003, only four days after his dear friend Johnny Cash, whose service he had just attended, and four days after he recorded his final song. Though the Wooley home on Santa Ana Road was torn down in the mid-2000s after it became eminent domain, the memories of life in the valley with her dad remain ever strong for Chrystie. He made sure her life included the bigger picture. “He believed in forgiveness and making amends,” she says, but forgiving his own father for the abuse and trauma of what he put his beloved mother through was the hardest thing he had to do in his spiritual life. Chrystie appreciates how her father’s transformation through AA has added “an extra layer of depth and knowledge about what that looks like” and how to relate to other people through it. It wasn’t perfect, but she feels “beyond blessed.”

She recently reunited with Rosanne Cash after decades of losing touch. “There’s a beautiful trust … just the history with our parents,” Chrystie says. “Rosanne and I just hugged each other; we just were so happy to see one another. After all these years, as I close my eyes I can smell the sagebrush in the mountains, and the lemon trees and the orange trees … Ojai will always be my home even though I’m here (in Nashville).”

She adds, “The older I get, the more I realize just how tenacious and wonderful a human being both of my parents were.”

“The Purple People Eater” still finds life today in many children’s catalogs and, most recently, in Nope, Jordan Peele’s 2022 neo-Western horror film. But the legacy of sobriety, found in Ojai, is unparalleled to Chrystie, who says “helping people attain their sobriety was such a Sheb Wooley thing to do. I’ve never met a man that embraced his humanness as much as my dad, but worked so hard to better himself … it was always a struggle to find that beautiful balance … that’s a legacy that he leaves that’s huge.” She is proud of her father for being “one of the hardest workers I’ve ever met in my life; he had (a) work ethic like nobody’s business. He never, ever, ever accepted no for an answer,” she says. “He made it in all these areas … I know he was very proud of all of it.”

“Walk the Line No. 2”

by Ben Colder/Sheb Wooley, 1963

As sure as day is dark and night is light Hey, I don’t think that I said that right Well anyway I’m flyin’ high tonight I feel fine, I walk the line I find it very very easy to be true But the question is, to be true to who…? ’Cause I ain’t got no one to be true to And that’s just fine, I walk the line

There’s winding road that runs right by my shack It was late last night I started back When a patrolman drove right up to find I paid the fine … couldn’t walk the line I find it very very hard to hit these notes But that’s the lowdown way this song is wrote I think I need a little something to wet my throat (sips) Thank you friend … I walk the line I find it very very easy to forget That Johnny Cash is the one that wrote this hit I guess I might get sued a little bit He was a friend of mine, I walk the line

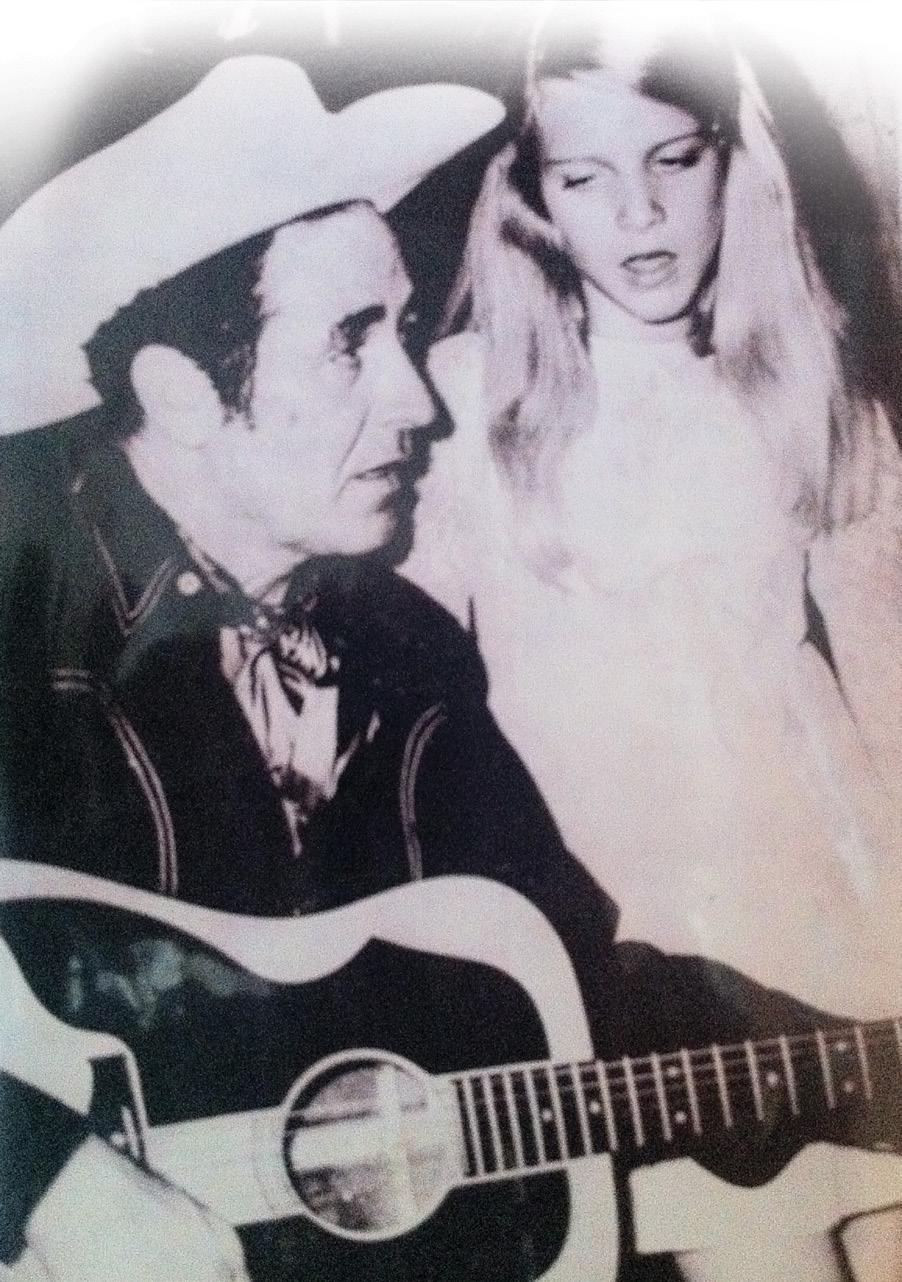

From left: The Wooley brothers, circa 1940 (Logan, Hubert “Skeet,” William Jr. “Dub” and Shelby “Sheb”); Sheb at the height of “Purple People Eater Fever” in 1958; Sheb Wooley Avenue in Erick, OK; a scene from Rawhide, Season 1, Ep. 20 “Incident of the Judas Trap,” 1959; Sheb and Chrystie sing “Only for You” at the Boys Club of Ventura benefit concert circa 1969.

There’s a reason a cowboy poet shepherded a policy that has made Ventura County one of the safest counties west of the Mississippi. That policy has led more than one crook to skip breaking the law in Ventura County just to avoid being prosecuted by its top lawman — District Attorney Mike Bradbury.

Bradbury’s “do right ethic” is demonstrated in his experiences with Mafia run-ins, headless bodies in Grimes Canyon, the Skyhorse and Mohawk case, the booking of Charles Manson before the Tate murders (Manson’s famous mug shot is the Ventura County Sheri ’s O ce booking photo), and Glen Campbell’s escapades, among many more. Those are only a few of the sensational tales in Bradbury’s new memoir, Law & Disorder: Confessions of a District Attorney.

A second book is already in the works. Whether a particular case is about bringing justice for the victim or punishment upon the criminal, or both in equal measure, the work of a prosecutor is ultimately about people, and the work touches each person di erently.

The longtime Ojai resident’s memoir recounts his years leading up to his tenure as Ventura County’s top prosecutor from 1978 to 2002.

His memoir o ers a glimpse into his first years at the District Attorney’s O ce, starting as a clerk under DA Woodru “Woody” Deem (1962–1973), then as a deputy district attorney under DA C. Stanley Trom (1973–