1

SCHOOL HISTORY DEPARTMENT WINTER 2022/23

KING'S

RETROSPECT

Foreword

We would like to thank all the contributors to the magazine, as well as the Sixth Form editors, Oscar Marsh, Giorgio Boiteux and George Gibbs, and to Kajsa Friberg for her help with the design and layout.

We hope you enjoy Retrospect magazine and perhaps will be inspired to contribute something to next year’s edition.

We have not published the History Magazine since 2019 due to the upheavals of the pandemic years, so it is with real pleasure that we are able to bring you the 2022 edition. You will find the usual eclectic mix of articles and topics, ranging from the use of 'Victorian Baby Murder Bottles' to the 'Siege of La Rochelle'.

In this issue of Retrospect we have included a tribute to the late Queen. In the following pages through different articles written by members of the History Department and pupils, we discuss who deserves the crown for the ‘greatest queen’ in history.

Winner of Book Token

We have decided that the £30 book token prize for the best entry in this edition of Retrospect goes to Olha Martyniuk for her article on the Dark Ages (p.26). We are now inviting contributions for the next edition of Restrospect. Please send articles on any theme or period in history that interests you to: cea@kings-school.co.uk

There is a prize of a £30 Waterstones voucher for the best article

Retrospect Articles Winter 22/23

The Legacy of Queen Elizabeth II - Ms Anderson

Why Marie-Antoinette is the Victim of Gossip and Rumour - Libby Mullen (MR)

Mary Tudor was not Myra Hindley Mr G Harrison

The Virtues of the Virgin Queen Ms C Anderson

Elizabeth Stuart, the ‘Winter Queen’ Mr I Bannerman

Cixi, Dowager Empress of China George Gibbs (MR)

The life and times of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire - Iona Bastin (WL)

The British Empire. A Source of National Pride or National Shame? - Barnaby Keen (GL)

The Stasi and State Surveillance in East Germany - Barnaby Carter (TR)

The Rise of Fascism in Italy and Germany Luca Sand (CY)

A Letter from the Trenches Molly Jones (MT)

The End of Apartheid in South Africa Samantha Yeung HH

Contemporary Art and Society Luka Zarkov (GL)

The Berners Street Hoax - Olya Bilyk (LX)

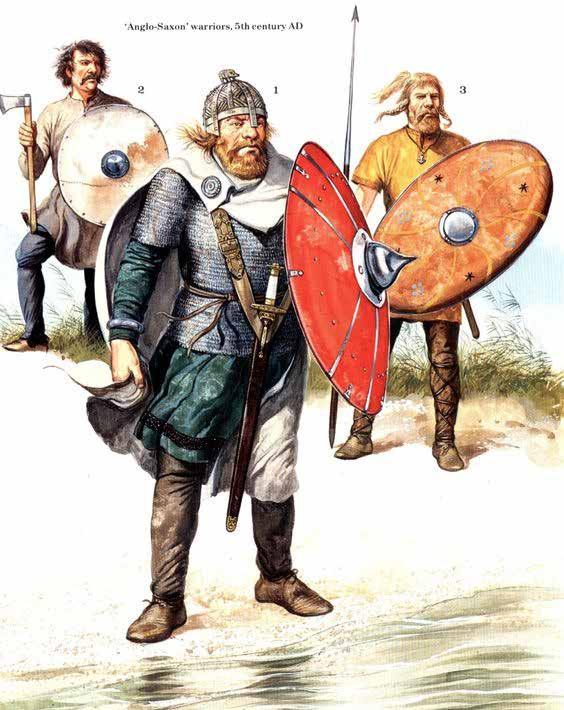

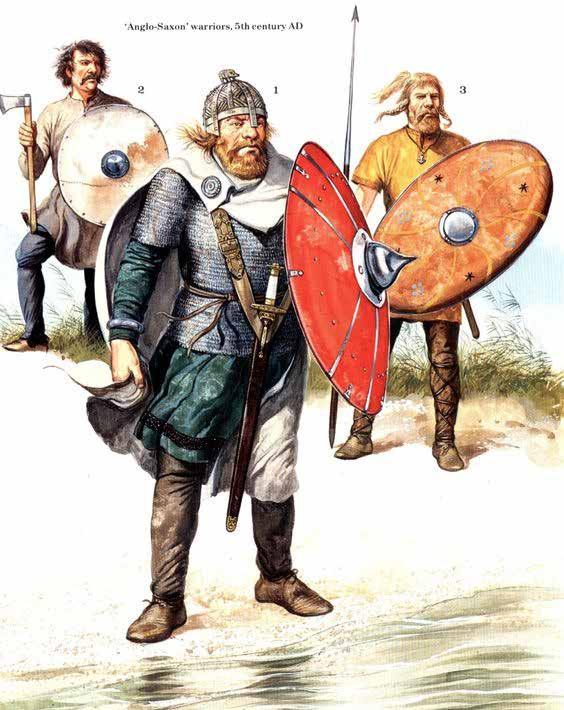

The Birth of Kingdoms, The Early Dark Ages in Britain - Olha Martyniuk (BY) 30

Victorian Baby ‘Murder’ Bottles Elise Batchelor (OKS) 32 The Siege of La Rochelle, 1627-28

From Foe to Family - William Child-Villiers (OKS) 34

A Cultural Tour in Bulgaria Breseya Clark (MT)

2

Page 3

4

5

6

8

9

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

25

26

The Legacy of Queen Elizabeth II by Ms Anderson, Head of History and Politics

heralded her reign a second Elizabethan age, invoking the concept of a ‘Golden Age’ as a panacea for Britain’s post-war malaise. When she was born in 1926 the reign of Queen Victoria was still within many people’s living memory; in this sense and in many others her passing represents the end of an era (a convenient, but nevertheless apt, cliché). She was universally respected and held in affection, both at home and abroad, for her steadfast commitment to duty and service and presence on the world stage over a sweep of time.

on the same day in 1945 - she asked people to “never give up, never despair”, evoking the spirit of the Second World War. The photographs of the Queen sitting alone at the funeral of her beloved husband Prince Philip in compliance with Covid-19 regulations, aroused sympathy around the world.

This feature was originally written as a celebration of the reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in her platinum jubilee year before her passing in September. In this series of articles by teachers and pupils, we herald her achievements and those of other remarkable queens throughout history.

Queen Elizabeth II was part of the nation’s consciousness for 70 years, during which time she was to many people around the world the symbol of Britain. As Head of State of the United Kingdom she played a vital role in the exercise of ‘soft power’ in a period when Britain had to forge a new identity as a post-imperial nation, as well as providing a sense of stability and continuity with the past.

That her reign spanned seven decades is, in itself, remarkable. She is the second longest serving monarch in history (the first being Louis XIV of France who reigned for 26,407 days compared to Elizabeth II’s 25,782 days) and Britain’s longest reigning monarch. In more recent years she came to be seen as a living historic figure, mythologised in her own lifetime in the Netflix series The Crown, and an embodiment of the 20th century. She worked with fifteen British Prime Ministers and met countless world leaders. Her first Prime Minister was Churchill, who, always alive to the advantages to be gained from allusions to the country’s history,

Many responded to her ‘normality’ and for her ability to connect with people on an individual level; she embodied the mystique of monarchy, combining the common touch with the ability to remain distant and unknowable to her subjects (in this she does bear a close resemblance to the first Queen Elizabeth).

She also clearly understood her role as constitutional monarch and avoided interfering in politics; in fact, she rarely made a misstep during the entirety of her reign, even though at times she must have found the need to keep her own counsel restrictive.

The changes she witnessed during her lifetime are astounding to contemplate. Upon the death of her father, King George VI, in 1952 she was the head of an Empire that still covered large swathes of the globe. Elizabeth II reigned over a period of decolonisation and the creation of the Commonwealth, playing no small part diplomatically in re-fashioning Britain’s post-imperial identity as an inclusive ‘rainbow nation’. She was witness to and played a crucial part in many defining events of modern Britain, including her handshake with Martin McGuinness, a former commander of the IRA (the paramilitary organisation that killed her cousin, Lord Mountbatten), a landmark moment in the process of peace and reconciliation that brought about an end to the Troubles. In the last few years during the Covid crisis her televised speech to the nation on 5th April during the first lockdown attracted 24 million viewers and on 8th May, the 75th anniversary of VE Day, in a television broadcast at 9 p.m. - the exact time at her father George VI had broadcast to the nation

British society and culture have transformed over the 70 years that she sat on the throne. The nineties were a notably challenging period when the royal family was beset by scandal and tragedy, and the Queen was accused of being out of touch with the public mourning shown at the funeral of Diana. But as the years ticked by marked by golden and diamond jubilees, and a bravura turn at the 2012 Olympics with Daniel Craig, her popularity only increased, only this past year reaching its apex in the celebrations for the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, with the already legendary Paddington sketch endearing her to all but the most die-hard republicans. That she remained committed to carrying out her formal duties as Head of State, meeting incoming Prime Minister Liz Truss and asking her to form a government only two days before her death and demonstrably frail, symbolises her dedication to the service of her nation.

So, is this ‘the end of an era’?

‘An era’ is a term utilised somewhat arbitrarily by historians to organise the past into distinct periods and whether it is true of the death of Elizabeth II remains to be seen. It is likely that questions will emerge about the future of the Commonwealth, Britain’s approach towards addressing its imperial past, whether Scotland continues to remain part of the UK, and even perhaps the survival of the British monarchy. We may be at a watershed moment in the constitutional history of our nation; time will tell.

But for now we remember the life and contribution of an extraordinary woman and acknowledge that she undoubtedly fulfilled the commitment she made in her speech on her Coronation Day in 1953:

“The ceremonies you have seen today are ancient, and some of their origins are veiled in the mists of the past. But their spirit and their meaning shine through the ages never, perhaps, more brightly than now. I have in sincerity pledged myself to your service, as so many of you are pledged to mine.

Throughout all my life and with all my heart I shall strive to be worthy of your trust.”

3

Image: Elizabeth II in the early years of her reign.

Why Marie-Antoinette is the Victim of Gossip and Rumour

Libby Mullen (MR)

Libby Mullen (MR)

Marie-Antoinette was a victim of misogynistic gossip and scandal. During her time in power, she was the subject of vile sexual rumours and objectification.

Marie-Antoinette was the fifteenth child of Maria Theresa, and she was simply seen as a commodity to be traded. She was married very young, merely 15 years old, indicating how she was inexperienced and not used to French court life. She was further criticised for her age: upon arriving in France on 14th May 1770 Louis XV commented on how child-like she looked, and how she did not have the full voluptuous figure of a woman. This demonstrates from the beginning Marie-Antoinette was exploited and used by the men around her.

Once married to Louis XVI she did not escape criticism or malicious rumours. She did not give birth to her first child until 1778, meaning there were eight years in her marriage to Louis XVI without her bearing children, due to the issues Louis XVI had in producing an heir. This led to Marie-Antoinette being ridiculed and embarrassed, despite the problems with conceiving not being her fault. She even received criticism from her own mother who complained about the time taken for her to produce an heir, indicating how she consistently met with humiliation and criticism for her inability to fulfil what was seen as a queen’s main duty.

Rumours about Marie-Antoinette’s sexual promiscuity were topics of gossip and scandal in France. She was rumoured to have had multiple affairs with both men and women. These rumours and obsessions with her sexual practices indicate the degrading, demeaning, and unfair image of Marie-Antoinette that they created (at least there was no online social media in those days…). Marie-Antoinette is further linked to the infamous comment, “Let them eat cake”, which she did not actually say, further indicating how this image of Marie-Antoinette of being shallow and out of touch is false. The main criticism of her concerned her profligate spending habits - she was even given the nickname ‘Madame Deficit’ - yet this criticism is exaggerated and taken out of context. As Queen of France her role was to make public appearances and create an image of magnificence

and splendour, which required lavish spending. Marie-Antoinette’s whole purpose at court was to produce heirs and look beautiful, and hence spending so much on accessories and clothes and Court spectacle was practically a job requirement. Furthermore, the major issues with the French economy were not caused by Marie-Antoinette’s expenses, but rather the extremely financially draining Seven Years’ War and the American War of Independence that France was involved in at the time.

Marie-Antoinette was simply a convenient figure of hatred, an easy focus upon which to target frustration for the problems in French society. She was never truly accepted in France; the group around her was referred to as the ‘Austrian Party’ and the French public arguably never saw her as their French Queen. Even nearing the end of her life Marie-Antoinette did not escape vicious rumours. Once imprisoned she had to endure prolonged incarceration while her husband was executed and her children were taken away from her. She waited nine months in prison alone before she was executed. When she was

put on trial, she was accused of being sexually inappropriate with her son; this charge was simply to humiliate Marie-Antoinette further, whilst Louis XVI who had committed more crimes, did not face such humiliating charges. She retained her dignity and showed poise and equanimity before her execution, showing her strength of mind and character even when approaching death.

To sum up, Marie-Antoinette was a woman who was the victim of misogynistic rumours and scandal. She was a young girl who had to leave her family and home and move to an unfamiliar country where she was objectified by the men around her and vilified by the public. The pejorative image of Marie-Antoinette is unjustified and masks her influence as an arbiter of style and culture as well as a leading political figure in her 18th century Europe.

4

Image: Portrait of Marie-Antoinnette by Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun, 1783

Mary Tudor was not Myra Hindley

Mr G Harrison

Mr G Harrison

The English, unlike the French, do not tend to add epithets to the names of their monarchs. ‘Louis the Fat’, ‘Louis the Stammerer’ and ‘Louis the Do-nothing’ – the chances were, for a French king, that they would become known for a characteristic they would not have chosen for themselves. Mary Tudor is one of the few English monarchs to be landed with a nickname. Adding ‘Bloody’ to her name does her no favours and stands in stark contrast with her successor, ‘Good Queen Bess’. She has, however, been unfairly judged and far from being a religious zealot, hellbent on forcing the Counter-Reformation on an unwilling population, she should be seen as one of the greatest queens of her era (and, indeed, any era).

Context, perhaps in the case of all candidates to be the greatest queen, is crucial. Before considering Mary’s reign, we ought to remind ourselves of the circumstances she faced before becoming queen. Bastardised in 1533 when her mother’s marriage to Henry VIII was annulled, she grew up as, at best, a semi-detached member of the court. Associated with those who refused to acknowledge both Henry’s supremacy over the English Church and those who saw his marriage to Anne Boleyn as adulterous, she was largely a non-person for anyone with political ambitions. Her reintroduction to the court in the 1540s and the legal reversal of her illegitimacy did little to improve her position and when her younger half-brother inherited the throne in 1547, she was a pariah figure when she refused to give up her allegiance to orthodox Catholicism. When Edward VI died, very few would have predicted that Mary would take the throne. Apart from Tudor blood in her veins, the odds were stacked against her. The Church was populated by evangel ical reformers, the Duke of Northum berland (acting as de facto regent) was a successful military leader and had the backing of the regency council, her op ponents controlled the capital and Mary was a woman. It is difficult to overstate the obstacle posed by her sex. England had never had a queen regnant (Mat ilda cannot qualify as such). Women were not trusted with political roles and save for Catherine of Aragon’s activities during the First French War of 1512-14, there was no precedent for what John Knox was later to call the ‘monstrous

regiment of women’. Yet she prevailed. Northumberland’s support faded, London opened its doors to her and she was able to replace the usurper, Lady Jane Grey, with the minimum of force.

The reason Mary was able to beat the odds was largely down to her personal qualities and that’s why she qualifies as a strong candidate to be the greatest queen.

Her determination to claim the throne came from within: she was not the puppet of an aristocratic faction but the instigator and leader of her own campaign. True, she had the Tudor name, but if possession is nine tenths of the law, her opponents had a grip on the treasury, the nation’s armouries and religious apparatus. Once in power, it was her hand on the tiller. Advised by both her own Privy Council and also by parliament that it would be folly to marry Philip of Spain, she nevertheless married him. Warned about the dangers of entering the Franco-Spanish War (and particularly on the Spanish side), she took her country to war against France. Faced with a Church hierarchy largely populated by reformers, she took England back to Rome and restored as much of Catholicism as was practicable. There was a terrible human cost to these actions, magnified by her short five year

reign, but judged by the standards of the century, she was no more bloodthirsty than her father. Henry’s response to the Pilgrimage of Grace had been blunt and brutal, with hundreds hanged. Burning so-called heretics both pre- and post-dated her reign and it is illogical to cast Mary as an anti-hero but rejoice in the actions of her half-sister, who had a cousin judicially murdered, priests burned and witnesses pressed to death largely in acts of royal self-preservation. Mary had guts, she understood that monarchs need to rule as well as to reign and she had a very clear sense of the realm she wanted to create. She set an example for English monarchs generally, not simply for queens.

If the argument for Mary does not persuade, then there is always Queenie, who ran a sweetie shop near Fye Bridge in Norwich from the 1950s to 1980s. Queenie’s face was covered in a white powder which was tinged pink as the massive rouge circles she put on her cheeks merged with the rest of her make-up. She seldom spoke but her collection of glass jars was the best in the city. Humbugs, sherbet lemons, pear drops, cola cubes, rhubarb and custards, strawberry bonbons, blackjacks and gobstoppers: who needs the flummery of a court when the shelves offer all the colours of the rainbow for eight pence a quarter? Sadly, her reign came to an end when she was sold to a travelling circus and the shop was redeveloped as Norwich’s first ever while-u-wait massage parlour.

The Virtues of the Virgin Queen Ms C Anderson

Elizabeth I may be a predictable choice for a teacher of the Tudor period, but it would be unforgivable to leave her out of the running. One reason she should be considered the greatest queen is due to what she overcame in her early life, which was nothing if not tumultuous.

Elizabeth was born the daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn, in 1533. Having challenged papal supremacy, broken with Rome and end-

ed a thousand years of Roman Catholicism in England, all for the production of a male heir, the birth of Elizabeth was something of a disappointment to Henry. Following the execution of her mother on the orders of her father in 1536 (in a show trial in which Anne was declared guilty of adultery with no less than five men, including her own brother), Elizabeth’s status immediately declined: she was declared illegitimate by Act of Parliament and had her title demoted. A signal of her precociousness is that, aged only three, she was said to have remarked upon her diminished importance to her governess: ‘how haps it, yesterday Lady Princess, and today but Lady Eliza-

beth?’ She was always one to stand upon her honour. It is telling that in later life Elizabeth rarely spoke of her mother and made no attempt to clear her name nor to declare the validity of her marriage to Henry VIII, an indication of the exercise of sound political judgement that was to be the hallmark of Elizabeth’s queenship – why risk stirring up discontent for the sake of rehabilitating the reputation of a mother she barely knew?

Her position improved somewhat in the 1540s when she, along with her half-sister Mary, was restored to the line of succession and to the favour of her father. She was given the best education of the

6

Image above: The Armada Portrait from 1588, denoting England’s victory over the Armada, but also its imperial ambitions (see the closed crown and Elizabeth’s hand on the globe), as well as full of symbols of Elizabeth’s ‘virgin queen’ status in the bows and pearls adorning her dress.

day by the leading humanist academics in England. As well as being a classical scholar, proficient in Latin and Greek and familiar with the works of Sophocles, Livy and Cicero, she was fluent in French and Italian. This all helped her greatly when she became queen in her dealings with foreign ambassadors, and is revealed in her oratorial skill and her ability to flatter, cajole and to win the argument, which was vital in the cut and thrust of 16th century politics.

Elizabeth found herself in a vulnerable position once again during the reign of her Catholic half-sister, Mary I. She was suspected of treason and taken to the Tower of London, and only survived due to the concerns over the succession held by some of Mary’s councillors. She was later released but kept under house arrest for the rest of the reign. Elizabeth was third in the line of succession and she must have thought for a long time that there was little to no chance of her ever occupying the English throne. But Edward VI’s death at only 15 years of age and the fact that Mary did not give birth to an heir and then her death in 1558 meant that Elizabeth inherited the throne, in line with the will and wishes of Henry VIII. She ascended to the throne at the age of 25, famously citing in Latin a line of scripture which read, ‘It is the Lord’s doing and it is marvellous in our eyes’. One of her great talents was that she was able to find the right words for the occasion.

Elizabeth ruled at a time when women were regarded as weak, inferior and irrational creatures and where it was widely believed that the rule of a woman was unnatural and would lead to disaster.

This is encapsulated in John Knox’s First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regimen(t) of Women – the title says it all and demonstrates what Elizabeth was up against. Much has been made of her single status. What could have been a political catastrophe (in that her duty, it was seen at the time, was to marry, produce an heir and secure the succession and stability of the realm) she converted into a triumph. She was able to rule as well as reign, declaring that she would have, ‘but one mistress here and no master’. Her carefully constructed image was an exercise in 16th century

PR expertise. Portraits were used to project her authority and to promote her virginity and link her to the Virgin Mary, as well as to transcend her gender by creating the ‘Gloriana’ cult through the image of a goddess-like figure. This can be seen to greatest effect in the Armada and Rainbow portraits (see below). Furthermore, her political judgement was impressive and her speech-making legendary.

Everybody knows about her inspiring the troops on the eve of the Spanish Armada with the words, ‘I may have the body of a weak and feeble woman…’, but her delivery of this to her troops, gathered in expectation of an invasion by Spain (the superpower of the day), wearing specially designed armour and riding a warhorse, shows Elizabeth’s command of theatre as well as her ability to appeal to the love and loyalty of her subjects and to stand as a symbol of the nation.

Her ‘golden speech’ towards the end of her reign is less well-known was just as effective. In what she knew was likely to be the last address to parliament of her reign, and after a difficult and tense session, the power of Elizabeth’s words had grown men leaving the parliament chamber in tears of emotion. And we haven’t even got to the victory

over the Armada, nor her establishment of a religious settlement that avoided the horrors of the burnings of Mary’s reign and was acceptable to the majority of the population, avoiding the bloodshed that was experienced on the continent in religious conflicts, or even the pioneering poor law legislation that was passed by her government.

Her reign is known as a golden age, a label we should rightly be sceptical about, but there is some truth in this in the flourishing of the arts that occurred, the prolonged period of peace and prosperity England experienced and the smooth succession upon her death in 1603. For the achievements of the period, as well as the personal abilities and attributes of Elizabeth, I believe she deserves the title of ‘greatest queen’: few, if any, can match her.

Image below: The Rainbow Portrait. Elizabeth still appears youthful despite this being from the later part of her reign. She is shown holding a rainbow with the Latin phrase meaning ‘no rainbow without the sun’ (I think we can guess who the sun is meant to be). Her dress is covered in eyes and ears, rather sinisterly symbolising her omniscience.

Elizabeth Stuart, the ‘Winter Queen’

Mr I Bannerman

Elizabeth Stuart was born a Scottish princess, raised in a now demolished English palace in Surrey, lionised as a protestant ‘phoenix’ by John Donne and married in a wedding so lavish that it nearly bankrupted England.

She reigned as Electress consort of the Palatinate for ten years and Queen of Bohemia for a single winter. After her husband’s defeat at the Battle of White Mountain (1620), she and her family were cast out of their lands and condemned to roam Europe as vagabonds, while central Europe was doomed to the almost unparalleled horrors of the Thirty Years War. During her remarkably eventful youth Elizabeth also found the time to have thirteen children, seven of whom predeceased her, as did her husband, Frederick of the Rhine, her father, King James I of England and her brother Charles I, who was decapitated in front of the Banqueting House in London on the 30th of January 1549.

Unlike her uncouth father and inflexible brother, Elizabeth always maintained a place of affection in the English imagination.

She had been named to flatter her third cousin, Elizabeth I, and was always consciously depicted in her image in portraiture. While her family were often viewed as parasitic Scottish interlopers, Elizabeth was associated with the halo of good queen Bess.

Elizabeth Stuart was highly educated, literate, a superlative horsewoman and fluent in several European languages, she was an accomplished dancer and musician as well as a witty conversationalist. The only gap in her education was Latin, which she had not been taught, as her father believed that knowledge of Latin was dangerous and unseemly in women given that it lent it itself to increasing their ‘cunning’. Elizabeth’s hand in marriage was eagerly sort across Europe but eventually went to Frederick of the Rhine. Unusually for arranged marriages they seem to have been utterly devoted to each other and Elizabeth nearly starved herself to death in grief at her husband’s eventual demise.

After a fabulously expensive wedding and celebrations which lasted two

months Elizabeth and Frederick decamped to the gothic splendour of Heidelberg in modern Germany. To please his wife Frederick built for her, in his castle, a monkey-house, a zoo, and a set of gardens so lavish that they were described as the eighth wonder of the world.

This peace was shattered by the decision of the nobles of protestant Bohemia to depose their Habsburg King and elect Frederick in his place. Frederick saw it as his duty to defend protestant Bohemia and wished to be a King rather than a mere Elector. Whatever his reasoning the decision was a disaster. Frederick and Elizabeth ruled Bohemia for twelve months before being expelled by the Hapsburgs. While this was a personal disaster for the couple, it was a catastrophe for the Bohemian protestants who were forcibly catholicized or exterminated and for Central Europe as a whole.

A greater percentage of the population of Germany was killed during the Thirty Years War than during either the First

or Second World Wars and the religious violence and persecution of the conflict inspired the horror of absolutism and Catholicism which led to the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution. While Elizabeth’s own family were not unscathed by the conflict they had unwittingly unleashed, they did prosper. Her son Rupert became the most famous of the Cavalier generals in the Civil War (his dog was believed by parliamentarians to have demonic powers) but it was her daughter, Sophie, who had the most lasting impact on history.

Sophie married the Elector of Hannover, was a great patron of science and her son became King of Great Britain as George I.

Every subsequent monarch of Great Britain and Ireland, including our own Elizabeth, has been descended directly from Elizabeth Stuart: gardener, vagabond princess and Winter Queen.

8

Image: Princess Elizabeth 'Elizabeth of Bohemia, The Winter Queen' by Robert Peake 1603

Cixi, Dowager Empress of China

George Gibbs (MR)

George Gibbs (MR)

Cixi, Empress Dowager of China, was born on November 29th 1835 in Beijing to a noble Manchu family. At the age of sixteen Cixi was sent to be a low-ranking concubine for Emperor Xianfeng; at the time, this would have been seen as a great privilege and it introduced Cixi to life in the royal court, yet it meant that she was entirely owned and controlled by the Emperor.

She quickly became one of the Emperor’s favourites and had a son by him. After the death of the Emperor, Cixi joined a triumviral regency that governed in the name of her son, who was in fact only 6 years old at the date of his accession. The name Cixi is honorific and means ‘Kind Joy,’ this was the name given to her after the death of Xianfeng.

Undoubtedly, she is one of the most powerful and significant women in Chinese history. There is still to this day ambiguity surrounding her life and reputation, however we can say for certain that her intelligence, strength and ruthlessness ultimately contributed to the modernization of China, i ncreasing foreign relations and bolstering trade.

Cixi came to wield significant political power in the last four years of the Qing dynasty and even after the termination of the regency in 1873 her personal

involvement in state affairs continued. Cixi supervised and contributed to the Tongzhi restoration which enabled the survival of the dynasty until 1911, during which time she was responsible for various effective, although sometimes belated, reforms such as the abolition of slavery and ancient torturous forms of punishment, as well as banning the barbaric practice of foot-binding.

Despite this, the credibility of her legacy has been the subject of some discourse by historians, with some arguing she was a tyrannical despot whose reactionary policies led to not only the downfall but the humiliation of the Qing dynasty.

Other, more sympathetic, revisionist interpretations argue that she was used as a scapegoat by communist and nationalist reformers and that her maintenance of political stability should be praised.

There is both misinformation and a lack of information surrounding the life of Cixi. It can be argued that she did what was necessary to survive in a patriarchal and toxic court.

Her decisions were pragmatic and she needed to display an element of ruthlessness and cruelty to strengthen the dynasty whilst also advancing a program of modernisation.

This is contrary to the image of an archconservative that was created of her. One could even go so far as to say that if she had lived a little longer, China may have become a stable, constitutional monarchy.

Arguably, she played a role in the dramatic modernisation of China, but because of her gender, she was forced to rule in the background.

The demonic portrayal of Cixi is unjust: although she did carry out ruthless acts, after a century of defamation, her reputation and life should be re-examined to portray an intelligent survivor who learnt to navigate and lead Qing politics for the best part of half a century.

9

A strong argument can be made that she deserves the recognition she has never rightly been afforded.

The life and times of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire Iona Bastin (WL)

Grenville, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and most importantly Charles Fox. It was Fox who caused Georgiana to be involved in politics during the General Election of 1774. Fox was a radical, wanting to limit the powers of the monarch which led to George III refusing to allow him to be Prime Minister. The Duke was happy to use Georgiana as an ornament at political dinner parties, but she wanted to go further, becoming actively involved and expressing her own thoughts and opinions. She attended the hustings with Fox, and these could be incredibly violent, often with window smashing and rioting which could potentially result in death. She also used to walk around Westminster canvassing voters for him, which defied the expectation that respectable women should not be so publicly involved in politics. This made her a target for pro-government propaganda which attacked her public image, even spreading rumours that she was exchanging kisses for votes. Fox lost the election to William Pitt the Younger, and Georgiana retired from politics until the Regency Crisis of 1788-89 of which she kept a detailed diary, which remains some of the most quoted source material for the period.

Georgiana Cavendish was one of the most remarkable women of the 18th century. Most well known for her notorious affair with Charles Grey and conse quent illegitimate child, she was also a political activist, socialite, gambler, and scholar, as well as a loving mother whose private life was filled with tragedy.

Reimagined in the 2008 film The Duchess starring Keira Knightly, she was a complex and interesting character who is well worth her fame.

Born Georgiana Spencer, she was married at seventeen to William Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire, who was ten years her senior. It was considered an illustrious marriage due to the good social standing of the Spencers and the wealth of the Duke, who was one of the richest and most powerful nobles in the country. He had great political influence due to the political structure of the time:

tions, which would attach themselves to rich patrons such as the Duke, who was a patron of the Whigs. Initially, the Duke was extremely reserved and icy towards Georgiana, but she had hoped that this public demeanour was contrasted with

her father. However, she found him to be just as cold behind closed doors, already having a mistress at the time of their marriage and preferring to spend time with his dogs rather than her. Georgiana suffered multiple miscarriages, for many years failing to produce the expected male heir to the dukedom which caused the rift between her and her husband to widen. She was a devoted mother, even to the daughter of one of the Duke’s mistresses, Charlotte, who she raised as her own.

The Duke’s influence in the Whig party meant that Georgiana became leader of the Devonshire House Circle, a political and social meeting place for the Whigs. It included many famous politicians and celebrities of the time such as Thomas

Georgiana was a great beauty and was painted multiple times by Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, the most famous portrait painters of the time. She was highly fashionable and was followed and imitated in everything she did, for example greatly influencing the growth in popularity of Bath as a place of leisure for the gentry. Georgiana was good friends with Marie Antoinette, who was also known for her elaborate hairstyles and outrageous fashion, and they certainly influenced each other. Georgiana initiated the craze for extravagantly designed hair that reached dizzying heights.

She created themed displays in her hair with ornaments, such as birds, fruit or even a ship in sail, and employed a resident hairdresser who was paid a higher wage than all of the female servants, and almost all of the other male servants including the Duke’s valet. She was the first to wear ostrich feather headdresses which she imported from Paris. These were three foot tall and started a fashion that caused feathers to become so scarce in England that fashionable women resorted to bribing undertakers for their horses’ plumage. In 1787, she was painted by Thomas Gainsborough with a huge black hat resting on her

10

Image: Gainsborough’s famous hat portrait of the Duchess painted in 1785-87

mass of hair, resulting in a trend for ‘the picture hat’. She also used her fashion in her political life, wearing a fox fur muff to demonstrate her support for Charles Fox.

Georgiana was a notorious gambler and was continuously in debt. Gambling was a popular pastime, one of few activities that men and women had in common, but Georgiana took it to a new level. It often took place at social events, such as at dinner parties, and could also be a political affair. For example, Charles Fox was known to stay all night at the card tables and consequently lost his fortune to gambling. The Duke’s cruelty and infidelity was in part the catalyst for this addiction. She tried to hide the extent of her debts from him as he would use it to constrain her, for example only paying off her debts if she allowed him to do certain things like living with his mistress, Lady Elizabeth Foster. She constantly asked her friends and relations to pay off her debts, including the Prince of Wales and the owner of her bank, Thomas Coutts, and spent her life dodging creditors who would chase her down the street or come to her house to try and claim their due. By her death she owed nearly £4,000,000 in today’s money. Upon being informed of this, her husband supposedly replied, “is that all?”.

Surprisingly, Georgiana became good friends with her husband’s mistress, Lady Elizabeth Foster, and there is speculation that she may have had a romantic relationship with her. However, Lady Elizabeth’s association with the Duke and Duchess was not necessarily out of love – her own husband was abusive and had kept Elizabeth from seeing her children. Therefore, the influence of the couple was invaluable in reuniting her with them. Lady Elizabeth seemingly encouraged Georgiana to have her affair with Charles Grey. While this might appear supportive, it could also have been a way of removing Georgiana’s moral authority over her.

When Georgiana became pregnant with Charles Grey’s child, she was given an ultimatum by the Duke: either give up Grey and the bastard, or she would never see her other children again. Georgiana chose her marriage and her children, going abroad to complete her pregnancy. On her return, she was forced to give the child, known as Eliza Courtney, to Grey’s parents to raise.

One of the paintings in William Hogarth’s election series, a satire on the electoral system of the 18th century. Voters are shown declaring their support for the Whigs (orange) or Tories (blue), while agents from both sides are using unscrupulous tactics to increase their votes or challenge opposing voters.

She inquired after Eliza for the rest of her life, even visiting her in secret. On her death, she gave Lady Elizabeth her blessing to marry the duke, but today we might question whether this was out of genuine forgiveness or pragmatism about the amount of control Lady Elizabeth had over her children’s future. Towards the end of her life Georgiana went blind in one eye from an untreated eye infection which also marred her famous beauty, forcing her to remain secluded in Devonshire House. She was not idle though and moving on from fashion she became interested in chemistry, spending time with scientist Charles Blagden and building a large mineral collection at Chatsworth. Finally, when her youngest daughter was introduced to society, she started entertaining again, rekindling her friendship with the Prince of Wales and becoming one of his main advisors. She died at only 48

years old of an undiagnosed abscess of the liver and spent the last days of her life in a state of insensibility and suffering from seizures.

Georgiana was a complex woman, who has remained in the public consciousness for several centuries. She was independent and free-spirited, and while this often got her into difficult situations, she was also an innovator and took the world on her own terms, whether through politics, fashion or science. She pursued her interests in the face of adversity and refused to be cowed by life’s vicissitudes, expressing her personality even when constrained by her husband and convention. She started life as a naïve and indulged girl, but even through torrid times she had a strength to her and displayed her creative and interesting character, which caught people’s attention then and through history.

11

"THE DEVONSHIRE, or Most Approved Method of Securing Votes," by Thomas Rowlandson, 1784

The British Empire A

Source of National Pride or National Shame?

By Barnaby Keen (GL)

In his book, "How Britain Made the Modern World", Niall Ferguson takes a traditional, positive view of the Empire. Ferguson lists some of the benefits of the Empire. Many of these are changes to systems of government that helped bring order to the colonised societies. In Ferguson’s view, the biggest political idea that the British introduced was democracy.

Democracy is based on the idea that all the people in the state are allowed to vote for the government of their choice, and help their chosen government make political decisions. This is just and fair, because it gives the greatest amount of happiness to the greatest number of people.

Furthermore, this system helps rule out the possibility of dictatorship. Ferguson writes about the ‘flows of culture’ in society and how this has helped Britain to become a highly multicultural country with diversity of food, religions and customs that have enriched society.

It has also helped other countries do the same. Along with this, Britain exported goods made in their country which were made from the raw materials import-

ed from elsewhere in the Empire. This allowed Britain to trade products with colonised countries and stimulate the flow of trade and capital.

Ferguson lists ‘team sports’ as one of the benefits of the British Empire. In the modern day, most people support a sport and the fact that two of the most popular sports in the world, football and cricket, were originally British, is definitely something that the British should be proud of. Also, the Commonwealth Games is a major competition in which a lot of former British colonies take part. Without the Empire this would never have happened. It could be argued that, in places like Australia, convicts and those at the lower end of the social ladder had a chance to make a fresh start in Australia. Many of these people built businesses, and now today many of these countries are thriving.

Ferguson writes of ‘representative assemblies’ as one of the benefits of the Empire. Today this happens in the Commonwealth where the global leaders of former British colonies meet to talk

about the economy, trade and politics and there is plenty of evidence to support that the British successfully exported ‘the idea of liberty’. Finally, the British helped develop infrastructure in the colonies. For example, they built schools, railways and colleges throughout Africa and India (amongst other places), even attempting to build a railway from Cairo to Cape Town.

Considering all of this, there could be a case to support Ferguson’s view that ‘no organization has done more to impose Western norms of law, order and governance around the world’.

Richard Gott, in his book Britain’s Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt, has the opposite view of the Empire and conveys its brutal side. During the years of Empire, the British were responsible for many acts of violence. If the people of the colonised countries did not obey British orders they would be brutally punished. In the Indian Mutiny in 1857 Indian soldiers of the Bengal Army were fired out of canons as punishment for the uprising. They had rebelled when they it became known that the guns they had to use were greased with pig fat, of-

12

fending both Hindu and Muslim sepoys and adding weight to existing concerns about forced conversion to Christianity. This demonstrates a lack of comprehension of and respect for local customs as well as brutal methods to keep control. This was also seen in the Amritsar Massacre in 1919 where thousands of people had gathered to protest against British rule of India and the British troops opened fire on unarmed people, killing 379 people in the space of 15 minutes.

These are just two examples of the repressive nature of British rule, showing the incompatibility of these actions with the notion that the British governors themselves had at the time as benevolent rulers. There was some integration, as the British did give non-British people jobs in the Empire, but they were often badly paid and were made to work in horrible conditions.

The higher ranked jobs went to the British who thought the natives of the colonised countries were incapable of doing the job well, reflecting the idea of the superiority of British values which is one of the defining characteristics of the British Empire.

Gott also writes that the British Empire sacked communities in a process of ‘cultural extermination’. Many pieces of art as well as sculptures and jewels were stolen from colonies and taken to Britain, leading to calls to this day for their repatriation. An example of this is the Koh-I-Noor, an enormous diamond that sits in the British royal crown.

In writing that there is a tendency to look at the Empire through ‘rose-tinted spectacles’ Gott is trying to say that we are only looking at the positive side to the Empire. He is challenging the view of the ‘benevolent empire’, which suggests that the British ruled in the interests of those they colonised and for their benefit.

In the countries that gained independ ence there are political and religious problems that persist up to today. When the Empire left a country it often left a divided community. For example, when the British left India in 1947, it led to a civil war between Muslims and Hindus which resulted in approximately 1 million deaths. India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, said that the British have ‘kept us poor’ and that Indians had to work in cotton mills on slave wages. Gott writes that the Empire ‘for those that actually experienced it’ was horrific. The triangular slave trade was the most inhumane of all. About 11 million

Africans were sold as slaves to British merchants and then sold on to plantation owners in the Americas in a system that was carried on for at least a century and a half and made immense profits for the many individuals and businesses involved in it. When being shipped the slaves were kept in unsanitary conditions and enclosed spaces and 20% of Africans never made it to the destination. To justify doing this, the British developed racial supremacy theories and the trade held back the social and economic development of African kingdoms, causing major problem that persist until today. Not only this but for a long time the credit for ending slavery was given to white British campaigners such as William Wilberforce, ignoring the fact that it only ended when it started to become less profitable and that British plantation owners and politicians such as George Hibbert and William Beckford continued to make the case for the continuation of the slave trade, as well as the enormous compensation payments made to plantation owners when the trade was finally abolished in 1833.

Another aspect of the slave trade that is often neglected is the role of the slaves and ex-slaves themselves in ending the practice. For example, Toussaint-Louverture’s revolt in Haiti in 1791-1804 succeeded in overthrowing French control and inspired revolts in the British colonies of Grenada, Barbados and Jamaica, and Olaudah Equiano was an influential campaigner against slavery in Britain. Ferguson certainly doesn’t defend any of the brutal, repressive actions by the British, but in arguing for the British Empire as shaping the

the modern world he casts the Empire as a bringer of progress and modernisation, failing to consider that many of these changes may have been naturally occurring, or that countries would have followed their own routes towards modernisation without the guiding hand of the British.

His is an out-dated view that has been widely challenged. Many modern historians argue that it is unacceptable to say that colonialized peoples did not have or would not have developed their own entirely valid forms of government, laws, and infrastructures without the influence of the British Empire.

Many historians argue that you cannot examine the British Empire without examining the more shameful aspects of Britain's past such as its involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

It also stripped many colonies and indigenous peoples of their land and vibrant cultures, for example, the Aboriginals in Australia and the indigenous peoples of the United States.

Both colonisation and decolonisation brought periods of violent upheaval in India and Kenya, and many other places. Practices such as the slave trade and Britain’s theft of the colonised countries’ history and culture are still controversial today, from the artefacts housed in the British Museum to the debates over fate of the statues of Cecil Rhodes and Edward Colston and the BLM protests. It seems the problems the Empire caused outweigh any benefits it brought and therefore, I do not think we should take pride in the British Empire.

13

Image opposite page: Wall painting from the head offices of the British East India Company, 1778, revealing the attitudes of the colonisers towards the colonized. Image above: The toppling of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol in 2020.

The Stasi and State Surveillance in East Germany

Barnaby Carter (TR)

East Germany was created in 1949 and lasted until 1990 when Germany reunified. It was the Soviet sector of post-war Germany, with West Germany created out of the British, American, and French zones.

Berlin, despite being in the Soviet sector, had a zone designated to the West. East Germany was behind the Iron Curtain and was a communist state. The economy of East Germany was considerably smaller than its western counterpart, with over 100,000 citizens who tried to escape between 1961 to 1988 because of the poor economic conditions and the limited rights.

Despite its name, the German Democratic Republic was neither a republic nor democratic and was a communist dictatorship in which there were no free elections nor freedom of movement. 9% of East Germans lived in poverty, and many were unhappy with the regime, which eventually led to its collapse. The Stasi was one part of this regime which caused a lot of suffering.

The Stasi police terrorised the citizens of the GDR for 40 years. The Stasi’s role was to spy on its own people, gathering information and brutally dealing with resistance to the government.

The Stasi kept files on 5.5 million East

Germans despite an absence of former offences, due to its informers.

The Stasi would bust plans to escape from East Germany, arrest or kill those plotting against the government of East Germany, spy upon those who posed no threat to the government, and spy upon people abroad (the Stasi had files on 500,000 Westerners).

For most of its duration, the Stasi was led by Erik Mielke (head of the Stasi from 1957 to shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989). He had joined the Communist Party at the age of 18 and ruled the Stasi with a steel grip. Like

14

many

The Stasi (Ministry for State Security) was the name given to the secret police that operated in the German Democratic Republic, better known as East Germany.

other policing institutions in the Eastern bloc, the Stasi was more loyal to Moscow than it was to its own state.

Mielke is a perfect example of this because of his ties to Moscow. Mielke escaped arrest in the Soviet Union and was subsequently recruited by the NKVD creating strong ties to Moscow.

The Stasi operated from their headquarters in Berlin, reporting directly to the leadership of East Germany. Most Stasi operations were based in East Germany, however one branch of the Stasi, the HVA (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung), designated its operations abroad, mostly in West Germany. They would take part in espionage, active operations (such as retrieving escaped citizens), and counterintelligence against NATO countries.

Many East Germans became informers because the Stasi offered them a physical reward (money), or they were blackmailed by the Stasi (promised immunity from a threat of prosecution) or the Stasi appealed to their patriotism in such a way that they were persuaded to spy on their friends.

There were around 200,000 informers in East Germany in 1989, East Germany having the highest proportion of informants and secret police ever, 1 in 60 people were involved by 1989. The Stasi would also spy on people by tapping into their methods of communication. For example, they would steam open letters, copy them, file them, and then reseal them. They would bug homes when they knew the inhabitants were out, and they would bug the phone infrastructure of buildings. They would send in informants with cameras hidden in their ties and use other obscure techniques to gather information. The Stasi would also resort to more violent methods, such as torture, murder and imprisonment.

One of the Stasi’s favourite methods of torture was sleep deprivation. They would lock the supposed offender in a very small cell, with room only to stand up. Even if you did manage to fall asleep a guard would wake you.

This was all to extract an often-false con fession, but was always effective, because someone who has gone a week without sleep will do anything to sleep. This was a preferred method of the Stasi because it left no marks on their body and could not be traced back to them.

Mariam Weber is a classic example of the East German regime and the role the Stasi played in everyday life. It was during the year 1968 (Mariam was 16), when the Prague spring was in full effect, when a

church in Leipzig was demolished by the state. This caused revolt amongst the citizens of Leipzig, which was put down very harshly by the Stasi.

Mariam and her friend thought that they should do something about this, and thus bought a children’s ink and stamp set. They proceeded to make leaflets with mottos such as ‘Consultation, not water cannon!’ to protest against the regime. They posted them to one of the boys in their class; the leaflets were reported, and Mariam was caught.

Mariam and her friend were placed in solitary confinement for a month and eventually broke and confessed. Whilst awaiting her trial, she decided to jump over the Berlin wall. She got close at Bornholmer bridge, within sight of the West, when she was captured by border guards. She was taken to Stasi HQ, and was deprived of sleep, despite telling the truth, until she told them an invented story about how she had met an escape organisation in a bar and had arranged her escape through them.

She faced many consequences and became an enemy of the state because of her attempt for freedom and was spied on until the fall of the Berlin Wall.

This story shows the brutality of the Stasi and their willingness to go to any lengths to achieve their means, even if it meant torturing a sixteen-year-old.

This brutal regime came to an end on 9th November 1989, when Günter Schabowski, an East German politician, gave an interview misreading new travel regulations, leading to crowds swarming the Berlin Wall, and with the civilians outnumbering the guards, the Berlin Wall fell.

A month prior, there had been mass protests in East Germany about the government, and the government had decided to loosen the border control slightly to satisfy the citizens. When handed notes in his interview about the new regulations, Schabowski mistakenly said on camera that the new regulations were effective immediately, causing a swarm towards the wall.

The guards did not open fire, both because they wanted the new regulations to be in effect and were fed up with the government, and because they mistakenly thought that the new regulations were effective already and that they should allow people through. Thus, the Berlin wall fell, and Germany was re-united within the year, causing the end of the Stasi. The Stasi file archives are held in Berlin, and if the Stasi kept a file on you, you can now request it from the archives. In total, the Stasi kept files on more than 6 million people out of the 16 million people living in East Germany by 1989, more than a third, the most information kept on a single population in human history.

East Germany has escaped from the regime of oppression and suffering that the Stasi represented, but current events in Ukraine demonstrate the fragility of peace and freedom in Europe. It is at times like this that we must remember regimes like the Stasi.

15

The Rise of Fascism in Italy and Germany by

Luca Sand (CY)

Luca Sand (CY)

Whereas other established states such as Britain, France and Spain, had a clear political structure and unified economy, the two nations at the centre of Europe were but a collection of small independent states, linked in loose coalitions. Their transformation into fascist dictatorships was accelerated by nationalism, the First World War and the devastating effects of the inter-war period. As Theodore Roosevelt once said: ‘People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made’.

Italy

Italy was united in 1861 under King Victor Emmanuel II, but only became fully unified in 1870 after the annexation of Rome and the Papal States. Despite this, the idea of an Italian nation meant little to the people, who cared not for nationalism, but instead were defined by ‘campanilismo’, a sense of identity linked to the precise location of their birth. ‘Campanile’, meaning clock tower, is the pride of each town or village in Italy, often hundreds of years old, and the focal point of every settlement to this day. The predecessor of the nationalist movement – irredentism - brought Italians closer together after Italy’s unification. The ‘irredente’ belief was that all areas considered to be culturally, linguistically, or historically Italian, including many areas outside Italy’s borders such as the Adriatic coast, should come under Italy’s rule. Italy carried little weight though and did not have political or military power to oppose Austria-Hungary, which ruled most of the ‘irredente terre’ in the 19th century. The future fascist party blamed the government’s weakness at the time for their failure to capture these lands.

By the turn of the 20th century, Italy had travelled a long way – nationalism was on the rise and the economy was significantly improving, turning Italy into an industrialised state.

The First World War was a major turning point in Italian history. Many bloody battles were fought with the Austro-Hungarians, mainly the Battles of Isonzo (all 12 of them), in which they lost hundreds of thousands of men. Despite being on the victor’s side of WWI, all Italy got in the Treaty of Versailles was small lands around the minor city of Trieste and a pat on the back, where they expected to receive the Adriatic coast, former Ottoman colonies and more. Many Italians felt insulted by this and viewed the Allies as having betrayed Italy. Mussolini and the Fascist party used this to their full advantage.

In the coming years Mussolini’s fascists gained huge amounts of support due to Italy’s struggling post-war economy and humiliatingly small gains at Versailles. Throughout the 1920s, Socialist and Communist parties emerged as the only prominent rivals of the fascists – until 1926. In this period, there were violent clashes in the streets and frequent political assassinations. Not long after, the fascist dictatorship was formed. In 1922 they marched on Rome. Due to this the Prime Minister resigned; the king could not form another government. With

no other liberal politician able to gain support for a government, Victor Emanuel invited Mussolini to become Prime Minister, and was thereafter reduced to a figurehead. By 1924 the Fascist Party had won the crucial 66% of the vote, and in 1926 Mussolini was granted the right to rule by decree and opposition parties were officially banned. Thus, the first fascist state in Europe was born, just over half a century after the nation’s birth.

Germany

In 1871, one year after Italy’s formation, the representatives of each Germanic state gathered in Frankfurt to create a German nation. Their first call of order was to draw out the boundaries. Due to a recent war and the inclusion of many non-Germanic peoples, Austria was excluded. They issued a Declaration of Rights and drew up a constitution. The new chancellor of Germany, Otto von Bismarck, formed a new government: the Reichstag. However, it had no say in his policies, it just approved laws and decided the annual budget. In the Reichstag, the Social Democratic Party was the one party that would never give support to Bismarck; he in turn despised socialists. Despite this, the Social Democratic Party was on the rise in the early twentieth century, with one in three Germans voting for it.

Simultaneously, nationalist sentiment

16

The rise of fascism in Europe was the pivotal event in modern history, and began in Italy and Germany in the mid-19th century.

Image: Italian fascist propaganda postcard on the Italy-Germany Axis, 1936

was growing. Just before WWI, Germany, not content with being the greatest European land power, engaged in a naval arms race with Britain, which dominated this field. Newspapers and politicians from both sides stirred up nationalist feelings, as citizens of each country cheered with every new battleship, each bigger, better, and crucially more expensive than the last. Eventually in 1910 Germany refocused its military spending on the army; however, the damage to Germany’s relationship with Britain remained.

Four years later, Germany was at war. After the murder of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, Germany pressured Austria-Hungary into sending an extremely harsh ultimatum to Serbia, one which could never be accepted. Germany gave the green light to Austria-Hungary for war, and so Russia backed Serbia; France backed Russia. This was an important step in gaining the support of the socialists, as Russia was now the aggressor.

After a long and bloody war, Germany had to concede. An armistice was signed on the 11th November 1918. A permanent agreement was signed in 1919 - the Treaty of Versailles. Its consequences were far-reaching. The sanctions imposed on Germany included: war reparations of billions of marks (money Germany did not have); losing all land gained by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Russia in 1917 and it had to reduce its army and navy drastically, could have no air force and had to demilitarize the Rhineland, the country’s main industrial area. It could be argued this sowed the seeds for the next war, some twenty one years later.

Between 1919 and 1939, Germany underwent huge social struggle and political change. The post-war government was established in 1919. The Weimar Republic, named after the small city in which it first met, could not gather in Berlin due to political tension and threat of socialist revolution. The major change from Germany’s pre-war government was the removal of the emperor, replaced by a president and chancellor to balance power. The Weimar Republic struggled to gain legitimacy and was handicapped by its association with national defeat and humiliation. Adding to this, there was never one dominant party, instead a coalition of different parties that constantly disagreed: on the

left, the socialist and communist parties; on the right, the nationalists who wanted to bring back the emperor and overthrow the restrictions of Versailles. Just two years after the republic’s creation, Germany was thrown into chaos by hyper-inflation of the currency. Between 1919 and 1923 political assassinations and violence plagued the country. One such murder was, by no coincidence, the man who had represented Germany at Versailles.

Adolf Hitler’s party was side-lined for most of the 1920s. It was called the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP); of right-wing ideology, it only included ‘socialist’ to appeal to workers. He wanted to destroy political divisions and create a unified Germany, with him as führer. In 1923 he marched on Munich with support from local army units in an imitation of Mussolini’s march on Rome. It was a dreadful failure, and Hitler was sentenced to prison; however, he received a light sentence – only five years - because he was acting for patriotic reasons and was released after only one year.

Had it not been for the Great Depression and the renewed economic turmoil it brought to Germany, it is most likely that the Nazis would never have become a power. In 1930 the government - a coalition - broke up. A subsequent election saw the Nazi party rise from 2.6% of votes to 18.3% as a result of rapidly increasing unemployment and social hardship. At the next election in 1932 they gained 37.3% and assumed

the place of the largest party in the Reichstag. Nationalist sentiment was high, accelerated by Hitler’s powerful and persuasive verbal skills, promoting himself as the nation’s leader. The old president Hindenburg was the only restraining force; he swore never to let such an intolerant man become chancellor. However, with his untimely death in 1934, Hitler assumed the role of chancellor and president.

The Nazi party grew substantially in the Reichstag, and with two thirds of the vote, Hitler began to ban other parties and crack down on opponents. Soon after, he had fulfilled his promise to overthrow the Treaty of Versailles. He reintroduced army and air force conscription, he sent troops into the Rhineland, and performed the Anschluss - the banned unification with Austria - in 1938. The Allies played a game of appeasement, hoping the Nazis would stop. By 1939, the Second World War had begun.

With the power of hindsight, it is quite clear that the rise of fascism in Europe could have been avoided, and consequently the Second World War.

However, human emotions are plain to see: revenge on the Western Powers at Versailles; vengeance for Italians and Germans during the inter-war period. The rise of fascism changed the course of the 20th century.

17

Image: Mussolini and Hitler at a rally

This letter was produced as a creative writing prep for Shells set on the nature of warfare and experiences of soldiers on the Western Front in the First World War

A Letter from the Trenches

by Molly Jones (MT)

by Molly Jones (MT)

Dear Annie,

It seems decades ago that I waved goodbye to you aboard the ferry, but time insists it was only a matter of weeks! Whitstable is distant to me now, comparative to the chaos of trench warfare, but I know that the day we sat together beneath the oak tree discussing our futures shall remain with me for a long time. I suppose fighting for my country with the lads of Whitstable is mine.

Of course, I am young and inexperienced, but it is difficult to believe that Jerry is just 500 yards away. We haven’t seen any real fighting yet, that’s why, as this is only our third week out here, but we’re still getting used to the duties of living in the trenches. My dear Annie, it is like I am at school again!: Stand-to at dawn, tidying the trench at eight, a nap after dinner and Stand-to again at six. The chap who’s head of our battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Wilson, has seen a fair bit of fighting in his time – he was involved in the Boer and the Boxers – so he’s not soft, but of course in the circumstances that’s not a bad thing.

I want to thank you for the socks and tobacco you sent with your last letter. A few of the men in our battalion have been having trouble with their feet, probably because of the mud and cold. But you can sleep easy knowing my feet are cosy and warm!

Annie, I know I shouldn’t write this but I must tell someone. I’m finding it hard to justify our presence here. I know, I know what I said before, but you must believe me when I write it was all a lie. And I’ve realised too late. No, how could I have written that? It’s just the tiredness, my darling, I’m not concentrating. But I want you to know. The first two weeks were exciting and completely overwhelming. (This is why I have just now found time to respond to your letter). Right and wrong had no place in my head, nor any comprehension of purpose, the reason we are in France in the first place. As I have said, we follow a strict routine, and learning how to use our Lee-Enfields and keep them in order occupied most of my thoughts. You see, it was all such a rush, being kitted up and shipped over to France, finding our way here, and now, squatting down in our trenches and making preparations for the onset of winter. Some of the men who’ve been here three years or more have told me what to expect, and the prospects are not pleasant. My dear Annie, these past few paragraphs have been all too gloomy. I know the Hun are only holding out, what with all the heavy bombardment our troops have been subjecting them to over the last few months. Soon we will break through their lines, and I shall come home to you victorious, holding you in my arms again once more. We shall go dancing at the club, and afterwards dine at the finest restaurant in all of London. This I promise to you, my darling, because here on the front line, these dreams and hopes are all I have to cling to. Right now, the trench is silent, save for the gentle puff of Billy’s pipe. We are resting, because at six begin our duties around the trench. Some of the lads are getting a little restless with these, as they say they signed up for ‘actual fighting’, not just ‘women’s jobs’. I hope it’ll die down, but if it doesn’t I can foresee a major row with Wilson. My character, as you know, is obedient in nature, but even I am starting to get annoyed. Already, there have been some breakthroughs along the front, but we have barely seen the spike of a Hun helmet. I know you will not like to hear this, but I long for some action. The unbearable state of limbo: the silence kept for days suddenly smashed by the thunderous roaring of shells, on and on, is driving some of the lads to delirium. Knowing that amidst the madness, you are there with me, keeps me safe and sane. How is life back in Whitstable? Does Old Ronnie still go fishing at four every morning? Does the bakery still sell the ‘Whitstable bun’, the one you created?

Time is drawing on, and I must get ready for Stand-to. There’s been a rumour we’re going over the top in a few days, but don’t worry your beautiful head about it, I’m sure there’s nothing in it. Give Joe and Harriet my love, and stay safe my darling. Let us pray the war will be over soon, and we will return and bring honour to Whitstable. All my love, Mick

18

A selection of other work produced for this task by (clockwise from top) Zara Brett, Emily Pack, Olya Bilyk and Victor Mali.

19

The End of Apartheid in South Africa Samantha Yeung HH

This article was originally written as a Shell history essay as part of the syllabus on how people campaigned for civil rights in the 20th century.

Apartheid, meaning ‘apartness’ in Afrikaans, was a set of laws introduced in South Africa in 1948 for the purposes of strict racial segregation of South African society and the dominance of the Afrikaans-speaking white minority.

It was upheld by an authoritarian political culture and police brutality against the black population. Internal factors, such as civil unrest, coupled with external factors, such as economic embargoes, the resolutions of the United Nations, sports and consumer boycotts heavily contributed the dismantling of Apartheid in 1991.

Both the external and internal factors are almost equally important and they worked together to bring about an end to this.

One of the factors that led to the ending of Apartheid in South Africa was internal pressure involving civil unrest and increasing militancy.

Examples of this include the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM), the Sharpeville Massacre, and the Soweto uprising and student protests. Launched by Steve Biko, the BCM was an influential student movement in the 1970s and was important because it became the voice and spirit of the anti-Apartheid movement at a time when both the ANC and PAC had been banned in the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre. Later on, the BCM was banned due to its suspected connections with the Soweto Student Uprisings.

Anti-Apartheid campaigner Steve Biko

In 1976, the inspired students of Soweto revolted in an uprising, which quickly spread to other towns in response to the government’s announcement that half of the subjects that pupils studied in schools would be taught in Afrikaans. Police fired at the 15,000 students who held a demonstration in Soweto, killing two young students.

This set a precedent, and by the end of the year, nearly 1000 protesters had died. It was important because the Soweto Uprisings had a very negative impact on South Africa's image overseas. Dramatic television coverage of police action in the townships was screened around the world, shocking international

opinion, destroying the government's attempts to end its isolation by establishing economic and diplomatic ties with other African countries.

The Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), a splinter group of the African National Congress (ANC) created in 1959, coordinated a national demonstration in 1960, for the abolition of South Africa’s pass laws. Later termed the ‘Sharpeville Massacre’, it was one of the first and most violent responses to the demonstrations protesting Apartheid in South Africa. Participants were instructed to surrender their passes and invite arrest, and around 20,000 black South Africans gathered near a police station at Sharpeville. According to police, after some protesters began stoning police officers and their armoured cars, they opened fire on them with submachine guns. As a result, around 69 protesters were killed and more than 180 were wounded, with around 50 women and children as casualties.

A state of emergency was declared in South Africa, making any protest illegal and more than 11,000 people were detained as a result of the massacre. The Sharpeville Massacre was important because it awakened the international community to the horrors of Apartheid

20

Image: Anti-Apartheid campaigner Steve Biko

Image: Violent response by police to the demonstration at Sharpeville.

and was the catalyst for the hundreds of mass protests by black South Africans, many of whom suffered casualties.

During the following five months, roughly 25,000 people were arrested, and the South African government subsequently passed the Unlawful Organisations Act of 1960 which banned anti-Apartheid groups such as the PAC and the ANC. Other major factors involved in the ending of Apartheid in South Africa were economic embargoes and external pressure. This was enforced through the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 (CAAA), Resolution 418, Resolution 1761, sports boycotts, and international condemnation. The CAAA was the first United States anti-Apartheid legislation, and it stated five conditions that would effectively end Apartheid that South Africa had to fulfil for the sanctions to be lifted. It was important because the sanctions brought by the United States and other western nations helped to bring an end to Apartheid by threatening to cripple their already dwindling economy at every level.

A resolution resulting in significant impact was the United Nations Security Council Resolution 418 of 1977. It imposed a mandatory arms embargo against South Africa and was done in order to prevent a further aggravation of a grave situation. It was important because of the extensive impact the embargo had on South Africa, which included the last-minute cancellation of the sale of D'Estienne d'Orves-class avisos and Agosta-class submarines by France, the cancellation of the purchase of Sa'ar 4 class missile boat from Israel, South

Africa's inability to purchase modern fighter aircraft to counter Cuban MiG23s over the SAAF in the South African Border War and the end of shipments by the United States of enriched uranium fuel for South Africa's SAFARI-1 research nuclear reactor.

Although it had produced minimal impact, resolution 1761 is also worth mentioning. In 1962, the United Nations adopted resolution 1761 condemning South Africa’s racist Apartheid policies and called on all its members to end economic and military relations with the country. It was important because it publicly faulted the South African government and encouraged Member States to do the same by cutting all ties with them. However, aside from media coverage, it was not effective as the main countries with strong trading links with South Africa did not uphold the resolution.

Furthermore, another example of external pressure was when international sporting organizations like the Olympics and the FIFA soccer federation began excluding South African teams from international competition in the 1960s and 1970s. In the early 1970s, workers at Polaroid in the United States became aware of the use of their company’s cameras and film in making the passbooks that all black South Africans were required to carry. They asked that Polaroid withdraw from South Africa and then organized a consumer boycott that ultimately led the company to pull out of the country in 1977.

Alongside that, the Frontline States enforced a boycott on South Africa,

limiting the market for South African goods that, coupled with consumer boycotts elsewhere and divestment by corporations, began to damage South Africa’s economy. Sports boycotts and international condemnation created an increasing sense of isolation on the part of the white minority government and its white citizens.

Ultimately, the internal and external factors were both crucial in the ending of Apartheid. But they would have had less of an impact if they had acted alone; both components worked towards the same goal.

The external factors of economic embargoes, UN resolutions, and sports and consumer boycotts amongst other things gave the South African government that push, toppling over decades worth of racial segregation and discrimination that were ingrained into every echelon of South African society.