6 minute read

The Work We Do

from 1199 Magazine

by 1199SEIU

The Work We Do Lab WorkersatNorthwell Health’sPlainviewHospital

COVID-19 shines a light on the critical, behind-the-scenes role of laboratory workers in

Advertisement

patient care. 1199SEIU represents laboratory workers at Northwell Health’s Plainview Hospital on Long Island’s North Shore. The 219-bed community hospital serves residents of Nassau County, which, by early February had a total of 130,933 COVID-19 cases. At Plainview, as at all hospitals, lab workers are integral in diagnosing and treating COVID19. The virus continues illuminate the role of so many unseen healthcare heroes and the critical role in healing the sick and moving the nation past the pandemic.

1. Michelle Rhem has been a Lab Processor at Plainview for 24 years. Her work helps keep the lab organized and running smoothly. She gets to work at 4:30 a.m. every day to manage orders, designate where specimens go, separate blood and urine samples, and ensure that staff, such as phlebotomists, are scheduled where they are needed to perform tests. “I know both sides of the lab coin,” Rhem says.

2. Laboratory Phlebotimist Fadil Pejcinovic has worked at Plainvew for 15 years. Before Plainview, he was a medical professional in his home country of Montenegro in the former Yugoslavia

3. Blood Bank Technologist Mary Jay has been at Plainview for over 20 years. She is a leading delegate and dedicated voice for lab members at the hospital.

4. Feri Mehryari

has been a Clinical Laboratory Scientist at Northwell Health’s Plainview Hospital since 1986. Since childhood, Mehryari has had a love of science that led her to the lab. In addition to the intellectual work of lab science, emotional sensitivity is necessary, says Mehryari. “My character [since a young age] has always been to help others and care for others,” she says. “I knew I wanted to be in the medical field, and in high school, I just loved the discovery part of lab science as well as the caring part.” She also emphasizes that the field’s educational rigor is often unappreciated. “We are required to have earned a BS degree, pass board exams, and maintain our licensure. There is a lot that goes into what we do.” 5. Laboratory Technologist Elaina Acero is a “new kid on the block” at Plainview, but she has over three decades of hospital lab experience. Her journey began in a college nursing program, where she decided that nursing wasn’t necessarily her calling. Acero says the analytical work of the laboratory was a better fit, and it still allows her to care for patients in her own way. “I love helping people. It is my number one priority. Even though I don’t see patients, I know I am able to make a difference in their lives,” she says. “Doctors rely on us for results, and without us, doctors and nurses would not be able to take proper care of their patients.”

3

– Feri Mehryari, Clinical

Laboratory Scientist

Saying Goodbye With Dignity& Love

At St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in NYC, morgue workers ensure a respectful transition for COVID-19 victims.

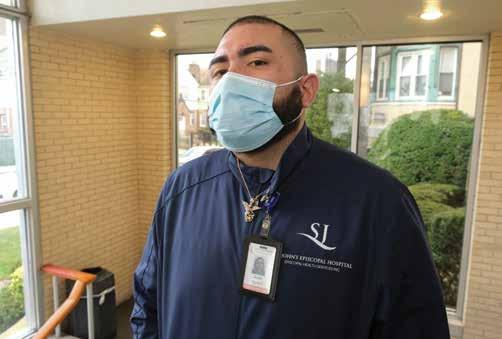

For Jesse Aguirre, a transport

messenger at St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in Queens, NY, COVID-19 work became personal in April, when the 29-year-old’s mother was admitted to the hospital with the virus. She died after a month-long struggle. As painful as it was to say goodbye, Aguirre also believes that God led him to the work at St. John’s, so he could be at his mother’s bedside.

“One of the blessings is that I got this job in time for me to be with her at the end,” he says. “Every 15-minute break I got, or any extra five minutes I had, I was running up to see her.”

Of all COVID-19’s cruelties, isolation may be among the worst. And perhaps most devastating is the fact that many who die from the virus succumb alone, isolated by the pandemic and lifesaving precautions necessary to protect caregivers. While many victims get to say farewell via FaceTime or Skype, too many others do not, denied the loving embrace of family, the warmth of a reassuring hand, or even a familiar, guiding voice. At St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in Far Rockaway, on the Atlantic Ocean-facing edge of New York City, a group of morgue workers has been doing all they can to ensure a safe and loving passage for those who do not survive COVID-19. Gary Hilliard, Bryon Howard, and Aguirre are all Far Rockaway natives with a close connection to the hospital and the people it serves. Senior Morgue Attendant Hilliard has worked there for nearly three decades in a variety of jobs. Transporter Messengers Howard and Aguirre joined the staff in early 2020, just ahead of the outbreak. For Hilliard, an 1199 delegate, the morgue job was supposed to be a stopover while resolving a grievance. He sees it differently now.

“I really believe that God put me

in this position for a reason,” says Hilliard. “When my grievance was done, I stayed in the morgue. I understood what this community was going through, because I have been here for many events, including Hurricane Sandy. And I knew that I should not fight [staying here]. I have learned enough not to fight against what God would have me do.”

At the onset of the pandemic St. John’s, like so many hospitals, was overwhelmed and underresourced. Far Rockaway, a now rapidly gentrifying neighborhood that has long been home to a diverse working class population, was hit hard by the virus. As caregivers struggled valiantly to save as many patients as possible, Hilliard, Howard, and Aguirre worked—with the help of numerous St. John’s staffers—to care for those who could not be saved.

For St. John’s patients who

“We say that even though people are gone, we have to treat them like all of our other patients, because the fact is, they are still here with us.”

– Jesse Aguirre, St. John’s Episcopal Hospital

had transitioned and come into their care, the team implemented an organized system to ensure that those who passed on were treated with the utmost dignity and respect. Facing as many as 100 bodies a day at the pandemic’s height, the trio—along with many of the St. John’s co-workers—made sure that remains were handled gently, names were spelled properly, and bodies rested securely until families and professionals could claim their loved ones and make arrangements.

For Aguirre, Howard, and Hilliard,

the painful statistics in daily news are not just numbers; they are family members, friends, and relationships of varying degrees of intimacy. This is the experience of Far Rockaway and too many communities of color across the U.S. during the pandemic. Their work is a hard reminder of what is important in life and what remains important after we are gone, says Aguirre.

“We say that even though people are gone, we have to treat them like all other patients,” says Aguirre. “Because the fact is, they are still here with us.”

“Coming and going to work, I always say a prayer,” confides Howard, whose grandmother was hospitalized with COVID-19 and survived.

“I spent a lot of time with my family—my mother and father and sister and grandmother. It made me appreciate them,” he adds. “One of the hardest things was seeing the families of patients who didn’t have closure and ended up passing alone.”

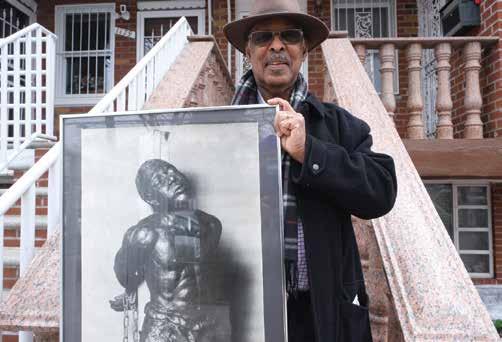

Gary Hilliard (top), Bryon Howard (bottom) and Jesse Aguirre (opposite page) work in the morgue at St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in Queens, NY. The team handled the bodies of many COVID-19 victims they knew at the community hospital. At the outset of the pandemic, the group was featured in a video by The New York Times.