7 minute read

Keep the

from 1199 Magazine

by 1199SEIU

Members urge lawmakers to avoid drastic cuts to the vital healthcare program. Keep The Medicaid Promise

Advertisement

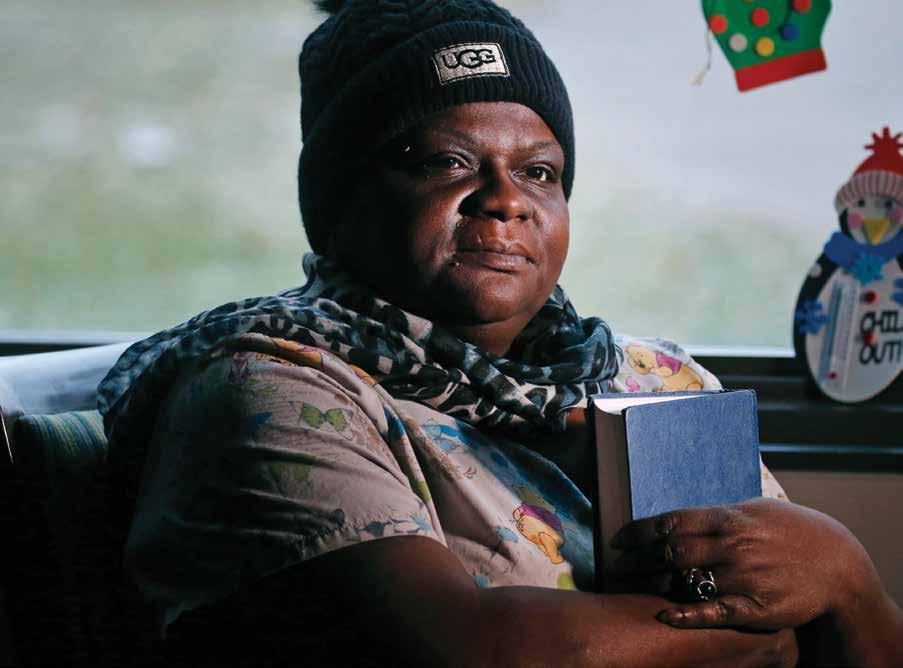

1199ers from around NYS mobilized in January, urging lawmakers to protect Medicaid.

For many of us, it may seem that Medicaid has been a constant part of American society—providing a much-needed healthcare safety net for seniors as well as disabled and low income adults and children.

But in fact, Medicaid was created a little over half a century ago, when Lyndon Johnson shepherded the pro gram through Congress as part of his ambitious Great Society program. At the time, the country was still reeling from John F. Kennedy’s assassination, and there was a steady wave of support for a more equitable society, built on the Kennedy Administration’s gains. At the time, many Republicans and conservatives fiercely opposed Medicaid and its sister program for seniors, Medicare. Many in the party fought bitterly to cut them ever since. Today we see a continuation of those efforts with the Trump Administra tion’s massive tax cut for the wealthy and the removal of $1.5 trillion from the federal budget, providing an excuse to cut funding to programs like Medicaid.

States depend on Federal dollars for their Medicaid programs, which ensures that all families can get the health care they need to get healthy and stay healthy. It allows everyone to see a doctor when they are sick, get check-ups, buy medications, and go to the hospital.

This year, New York state officials announced a $2.5 billion gap in avail able state funding for Medicaid. That puts a big target on the back of safety net hospitals and other vital services.

In response, 1199ers are mobilized and urging elected official to reject damaging cuts to this vital lifeline for millions of New Yorkers. They can do so with new revenue from the wealthy and corporations and a focus on rooting out profiteering and excess administrative costs in the system. In January, 1199ers went to Alba ny to lobby lawmakers to Keep the Medicaid Promise and avoid trying to balance the budget by threatening the health care of vulnerable people across the state.

Lauren Jarushewsky, an Occupa tional Therapy Assistant at the Orzac Center for Rehabilitation in Valley Stream, emphasized how the quality of care her patients receive would be affected.

“As therapists, we went into this field to help people meet their poten tial, but with cuts it’s very stressful to try to do that. Of course, we get the job done, because we’re dedicated professionals, but when patients are discharged early it’s stressful on them and stressful on their caregivers at home. They affect everyone.”

Danisha Marrero, who works as a Certified Alcohol and Substance Abuse Counselor (CASAC) in the Opium Addiction Program at Mt Si nai Beth Israel in New York City, says Medicaid cuts have a domino effect on vulnerable populations.

“For me, this isn’t just about the opiate crisis. When you talk about making these cuts you are talking about all kinds of treatments. Hos pitals will have to turn people away. Those who need them won’t be able to access medications on which they depend. I can tell you cuts would hurt my patients in many ways. And that’s a significant number of people; about 85% of the people I see rely on Medicaid.”

Marrero says the answer does not lie in taking money out of the budget and that caregivers, who can be the voices of their patients, need to be brought into the conversation.

“We have a broken system and it has to be fixed. What am I supposed to say to a patient who has had their Medicaid cut and could die without treatment? We need to fix this prob lem at its root,” Marrero emphasizes. “The fact that some of our elected officials even entertain making these kinds of dangerous cuts is really con cerning. It tells me they don’t understand what is really going on with our patients and in our communities.”

“When Medicare cuts went into effect last October, we lost 3 Occu pational Therapists and 3 Physical Therapists,” adds Jarushewsky. “More Medicaid cuts will just cause even more to be taken away. We will have less time to spend with patients and must do more for our patients in less time. As professionals we still must give our patients the same level of care, but now we have to do in 30 min utes what used to take 60 minutes.”

With a new owner ready to gut their contract, unified workers took a leap of faith and pushed management back to the bargaining table. Fend Off Attack on Their Contract Capital RegionCaregivers

In dire straits due to their financial mismanagement, for years The Lutheran Care Network (TLCN) operated their Delmar, NY facilities, Good Samaritan Nursing Home, and an assisted living facility, Kenwood Manor, on a shoestring budget. As the buildings deteriorated, the workers were continually challenged by short-staffing and diminished supplies. Making things worse, the employer paid the workers’ Health Benefit Fund only sporadically, creating uncertainty for the caregivers whose benefits could end at any time. No one was surprised in December when TLCN filed for bankruptcy. But, with the facilities in shambles, only one for-profit corporation, Centers Heath Care, stepped up as buyers.

Concerned that the potential new owner would not recognize their union contract Good Sam and Kenwood members held meetings, rallies, press conferences, and an informational picket to let Centers know that their 1199SEIU collective bargaining agreement would not be undermined. Workers were clear that they would not put patient care at risk by aggravating short staffing and losing experienced caregivers.

Teneisha Addison, a CNA at Good Sam for the last six years, was emotional during a January press conference held by Good Sam and Kenwood workers.

The message fell on deaf ears. In a bankruptcy court motion, both Centers and TLCN requested that the workers’ contract be gutted ahead of any purchase. With the bankruptcy judge about to decide the future of the facilities and their jobs, TLCN workers realized they needed to speak louder and took a leap of faith. Somewhat reluctantly, they voted in January to send a 10-day strike notice. Pushing the envelope worked and within a few days, Centers Health Care came back to the bargaining table. At press time, negotiations were under way, with workers prepared for tough, critical bargaining ahead of them.

Rita Hyman, a CNA at Kenwood Manor, remains cautiously hopeful in the stressful situation.

Good Samaritan and Kenwood Manor workers are not alone in their fight.

“That’s a great thing about being in a union. Our story is here in the Albany

Lauren Malic earned her RN with help from the 1199 Training Fund after relocating to Miami after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

area, but there are 1199 caregivers who work at Centers facilities throughout the state and we have a lot in common. We all count on the wages and benefits negotiated in our contracts, because we need to take care of our families at the same time we care for our residents,” said Hyman.

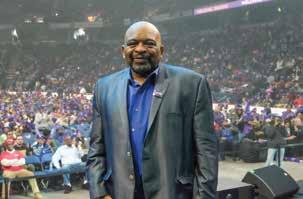

John Makoyi, a licensed practical nurse at Good Sam, has been an outspoken leader about the impact of TLCN’s bankruptcy.

“Our fight is for all of us—for every caregiver, every resident, and every family who could be jeopardized by employers like The Lutheran Care Network or the Centers, who see profit and the bottom line before they see the human faces of long-term care,” affirmed Makovi. “Whether we are in New York City, Albany, the Hudson Valley or Buffalo, we can’t allow Centers, or any other employer to lower the standards we have fought so hard for and won and to put greed before quality care.”

Institutions owned by The Lutheran Care Network were up for sale, leaving workers with an uncertain future— including loss of their health care— but they recently forced a potential buyer back to the negotiating table.