6 minute read

Holidays for hermits

Travel

Retreat from the world

Advertisement

For his new book, Nat Segnit visited Britain’s quietest monasteries and islands to talk to monks, hermits and recluses

Sara and I sat on the pebbles as Zoë, her dog, skittered ahead on her sharp claws. Like a spiritual goal, Zoë disappeared at intervals, where the beach dipped or a boulder proved too irresistible a surface not to pee on.

Sara had recently returned from a 40-day, silent retreat in the Sinai Desert.

‘I like desert silence better than any other sort,’ said Sara. ‘Because it is very, intensely silent.’

I had come to south-western Scotland to talk to Sara Maitland – writer, Catholic convert and recluse – about her decision, 24 years ago at the age of 47, to break with family and friends and commit to a life of silence and solitude.

Compared with the great highland wildernesses of Wester Ross or Sutherland, Sara’s neck of the woods, on the depopulated peat moors of northern Galloway, is something of a hideout in plain sight, close to the English border and overlooked by the hordes of tourists whistling past on the A74 to Glasgow.

From her isolated shepherd’s cottage high on the moor, we had driven down to the coast to visit Ninian’s Cave, reputedly the personal retreat of a fifth-century missionary whose church at Whithorn, five miles away, has a claim to being the birthplace of Scottish Christianity.

We were alone, save for Zoë. Just above the horizon, roughly where Ireland ought to be, the winter sun had diffused into a smear of blinding light, transmuting the stony beach into gold. We sat and listened to the waves bid the shoreline be quiet. From somewhere inland, a sandpiper’s cry registered less as sound than as part of the stillness.

What sort of person, I wondered, would find this degree of tranquillity wanting – to the extent of feeling a need to retreat to the Egyptian desert for 40 days?

Over the 18 months I spent researching my new book on spiritual and secular retreat, I talked to monks, hermits and recluses from suburban Manchester to San Francisco, the Aegean to the Arctic Circle.

If anything united them, it was this: a dissatisfaction with what we might ordinarily think of as isolation, a yearning to go deeper into the silence and solitude which, for Sara, cleared the way for a radical encounter with the Divine.

For a crowded island nation, the UK offers no shortage of opportunities to distance yourself from humanity. The island of Easdale, off the coast of Argyll, was once a thriving centre of the slate industry, but now has a population of less than 70. (Up, admittedly, from the early 1960s, when it fell as low as four.)

If you miss the ferry from Ellenabeich, in summer you can swim the 60 yards across to the island, and bathe, alone, in the rain-fed slate cuttings, or sit on the cliffs and watch for minke whales.

Less far afield, at the Sharpham Trust near Dartmouth, experienced meditators can undertake a week-long, silent, solitary retreat in a hut on the wooded fringes of the estate: a West Country Walden, with nothing but a bed, a wood-burning stove and a view of the Dart though the trees.

Tranquil surroundings, of course, are no guarantee of their inner equivalent. The conventional wisdom that retreat is

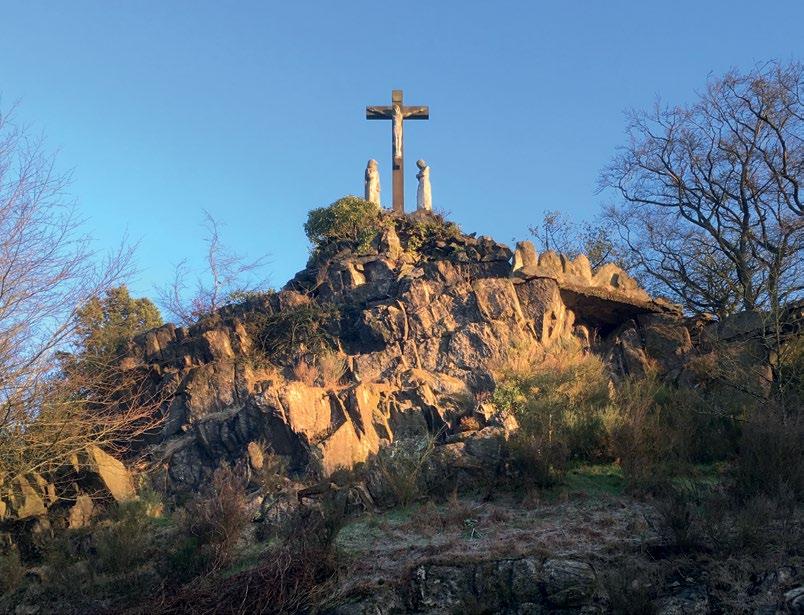

Trappist Mount St Bernard Abbey (above) and Calvary (top). Right: cell & cider lunch, St Hugh’s Charterhouse

more a state of mind than a place was borne out most memorably in Salford, between a low-rise housing estate and a branch of Tasties Takeaway.

The Saraniya Centre is an unlikely outpost of the Panditarama Monastery in Yangon, Myanmar. It’s housed in a peeling, Edwardian villa, where, at the time of my stay, U Tarraka, a stern-looking monk in saffron robes, had been posted from Yangon on secondment.

The style of meditation practised there is in the Mahasi tradition, which meant that everything – walking, eating your cornflakes and tying your shoelaces – had to be done with excruciating slowness.

We rose at four, and spent the next 18 hours in alternate sitting and walking meditation, nipping to the loo or to the dining hall at breaktime as if we were wading through a viscous medium. It was like an experimental zombie movie: horrifying, but low on drama. Talking was forbidden, as were sex, killing, telling lies, listening to music and eating after midday.

The aim was awareness: to give ourselves the chance, as we inched across the carpet, to notice not only each sensation but all its component parts, the sequence of millimetric shifts that went into each footstep; the tiny discrepancies in depth and duration between one breath and the next.

It was enough to drive you nuts. Maintaining satipatthana – mindfulness – without let-up involved a degree of tedium that was often indistinguishable from pain. For the beginner, at least, it was an exercise in Olympic (or sectionable) pedantry, Knausgaardian attention to minutiae and Warholian immersion in boredom.

The only response was to press on and embrace the pain – something made that bit more painful by Greg, one of my four fellow retreatants, who not only ate like a warthog but was in the habit, passing me on walking meditations, of leaning in and whispering, ‘I’m so f***ing bored.’

And yet, three or four days into the ten-day retreat, something clicked, or shifted, and the effort to concentrate, formerly so difficult, became selffulfilling, with the result that a calm descended, the like of which I had never experienced – no matter that I was in the middle of the city, and the kids in the housing block opposite were blasting dubstep through their open windows.

Still, in the contemplative traditions, silence loads the dice in favour of fulfilment. ‘When thou prayest,’ says Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, ‘enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret.’

At St Hugh’s Charterhouse, the UK’s only surviving Carthusian monastery, near Horsham in West Sussex, I spoke to Fr Cyril Pierce, who entered the order aged 27 in 1960.

Of all the Catholic orders, the Carthusians are the most enclosed and committed to silence. Just as Sara Maitland felt the urge to go deeper into stillness, it’s not uncommon for Carthusian novices to be ex-Benedictines or Cistercians grown dissatisfied with the relative leniency of their rule.

The silence is very deep here. To become a Carthusian monk, Fr Cyril told me, was not a matter of acquiring virtues. ‘It’s getting stripped down,’ he said. Divesting yourself of all impediments to prayer. ‘It’s only bit by bit that you begin to hear Christ.’

Later, I spent a few days at England’s only Trappist monastery, Mount St Bernard Abbey in Leicestershire. As at Parkminster, I was struck by the great outbreaks of noise that characterise the monastic round, the clamour of bells and the singing of the liturgy, both as acts of praise and as delineators of the silence that surrounds them.

It was the same at the Benedictine Abbey of Solesmes, in northern France, and at the other Catholic and Orthodox monasteries I visited around the world. Attend Mass, and the hush that follows the Alleluia feels like an opening on another dimension.

This was the intense quiet Sara Maitland was aiming for, where the Carthusians began to hear Christ. Irrespective of your faith or lack of it, it was hard not to perceive this as an awakening.

Nat Segnit’s Retreat: The Risks and Rewards of Stepping Back from the World is out now (Bodley Head, £18.99)