4 minute read

History

Parliament’s history boys

The best MP-historians, from Macaulay to Churchill david horspool

Advertisement

Being a historian should be a good preparation for a future political career. Just think of the adage ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’

But historians have long been in a tiny minority in the House of Commons when compared with lawyers, journalists, trade-union leaders and business people.

There are some honourable exceptions among honourable members. Until he jumped ship in 2017 to become Director of the V&A in London, the best-known MP historian of recent times was Tristram Hunt, former Labour member for Stoke-on-Trent Central.

Hunt, who has just published a biography (highly recommended) of the Potteries’ favourite son, Josiah Wedgwood, has a knack for tackling thorny subjects with authority and a light touch, from the ‘frock-coated communist’ Friedrich Engels to the rise and fall of the Victorian city.

As an MP, he put his historical training to good use when campaigning to save the Wedgwood Museum from closure and its collection from being broken up when the parent company went bust.

Hunt’s departure followed that of an MP whose historical contribution came later in his political career: William Hague, who moved up to the House of Lords in 2015. Hague’s widely praised life of Pitt the Younger was followed by an equally well-received biography of William Wilberforce.

Whether Hague or Douglas Hurd was the better Foreign Secretary might be open to debate, but not many readers would pick Hurd’s lives of Peel or Disraeli (damned by a reviewer as ‘respectable and competent’) over Hague’s study of his fellow wunderkind, William Pitt.

There are still historians left among today’s MPs, though none as high-profile. Labour’s Chris Bryant was a priest in the Church of England, not a historian, before he took political orders. Still, he has established himself as a forthright analyst of past injustices, perpetrated either by the British aristocracy, of which he wrote a ‘critical history’ in 2017, or by the wider Establishment, as with the subject of his recent group biography of the gay MPs who resisted appeasement and bore the brunt of conventional homophobia for their troubles (The Glamour Boys).

On the Tory side, there are two historians who take a longer view. Chris Skidmore, Member for Kingswood, in Avon, is an expert on the last Plantagenets and the Tudors. If that sounds rather removed from contemporary concerns, Skidmore might disagree. He has mused that ‘If people have nothing to lose, they will take action.’ Though he was referring to those around Richard III, the insight still applies today.

Another Tory, Alex Burghart, who represents Brentwood and Ongar, is a former tutor in Anglo-Saxon history at King’s College London. His study of Mercia is still hoped for. He keeps his hand in with historical contributions to various publications, and as host to lectures on subjects not usually given much airtime at Westminster, such as one to come on Athelstan and the origins of the English Parliament. There are others for whom historical claims could be made, including the Leader of the House and the Prime Minister. But

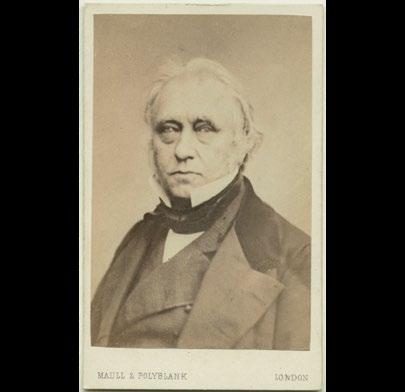

Thomas Macaulay, MP and historian both Jacob Rees-Mogg and Boris Johnson have written history books of the sort that are politics by other means: the former in his encomium of Victorian virtues, the latter in his embrace of Winston Churchill as a supposedly Johnsonian predecessor.

A more convincing MP biographer of Churchill was Roy Jenkins, who also wrote historical biographies of Gladstone and the forgotten Liberal radical Sir Charles Dilke, whose reputation he revived almost single-handedly in his 1958 book.

Churchill himself was almost as much a historian as a politician, especially when the politics wasn’t going so well. He told the House in 1948 that he considered ‘it will be found much better by all Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself’. As well as writing the history of his own times, he drew on historical inspiration, whether evoking the example of a Drake to toughen the sinews against invasion, or trying to apply the lessons of his ancestor Marlborough’s campaigns to contemporary embroilments.

One of Churchill’s greatest models as historian was another MP, Thomas Macaulay, whom he had loved ever since winning a prize at Harrow for memorising 1,200 lines of Lays of Ancient Rome.

Despite Churchill’s colossal reputation, and colossal sales of history books, it is to Macaulay that we should really offer the palm as MP historian. After all, even Churchill himself never conceived of a theory of historical change – what we know as Whig theory – that is still invoked and attacked more than 150 years after his death.

Macaulay (1800-59) may have started his parliamentary career in a rotten borough before embracing reform and representing the new industrial constituency of Leeds. But he is, on this evidence, the greatest MP-historian on either side of the House.