Single-Family House in Belgium: History, Present and Future Impacts

Oleg Asoiev, Kamilla Jolicoeur

Introduction

For many critics the Belgian landscape is disordered and hideous. It is composed of unplanned developments of settlements that started along roads and expanded. Articles dealing with urban sprawl, landscape and housing are full of severely critical opinions. For example, De Meulder describes Belgium as “a land of laissez-faire, where the cacophonic juxtaposition of designs delivers surprise after surprise, where an intense poetry lurks side by side with a nauseating banality behind the commonplace of everyday habitation. This chaotic urban landscape seems to lack any coherence whatsoever”1. From Renaat Braem’s point of view, “seen from an aeroplane, Belgium must look like a patchwork quilt sewn together by a lunatic out of God-knows-what garbage, and then spurned with disdain by an invisible giant who strews about the contents of boxes of bricks, creating the ugliest country in the world”2. Oftentimes, Belgium is compared to the Netherlands, ironically, the example of the “best” urban planning is the closest neighbour: “it is not a secret, that many Belgian architects, urban designers and planners go on repeated pilgrimages to our promised land to the north, the Nederlands”3. Probably such a close good example of planning is a reason for such harsh critique. However, not everyone shares this rigid opinion about the Belgian landscape. According to W.-J. Neutelings, the Belgian residential condition includes variety, flexibility and urbanity, whereas C. Weeber “promotes the unruly Belgian model as a breath of fresh air after the streamlined and utterly dull housing output of the Netherlands”4. The Belgian population also does not share this analytical top-view critique of the landscape and of the housing situation. Indeed, the urban sprawl is still on a rise; eating up what is left of rural parcels of land. The entire countryside has become such as an enormous suburb. It is dependent on major cities, as well as on cars. At the heart of sprawl and of suburban lifestyle stands the single-family house, a key element in the formation of the current Belgian landscape. The single-family house, a rural-suburban typology, is a strong Belgian ideal, which from the user’s point of view does not seem ugly or wrong. Tracing back to the beginning of the single-family house boom, this paper tries to demystify the single-family house phenomenon that is so deeply rooted into the Belgian culture. This will be done by looking at historical events and policies and their impacts on the current situation of sprawl and the single-family house phenomenon, as well as by analyzing the past and its influence on the future of suburbs and single-family houses.

History

Industrial Revolution

During different periods of time and for different purposes, the single-family house model was promoted to the population. The intensive encouragement to move into suburban houses began with the industrial revolution. Around 1825, Belgium was the second European country, after Britain, to go through industrialisation. This generated an important flow of workers towards the cities, which was followed by a rapid development of small and tightly arranged dwellings5. The bad hygienic conditions led to poor living conditions and epidemics, such as the cholera epidemics that happened in 1832, 1845, and 1866. Frightened, the wealthy were the first to leave the cities for city-border villas. To the Liberal and the Catholic elites, not only the sanitary situation, but also the imminence of rebellions that masses of workers could trigger was a problem. Indeed, deadly riots occurred in 18866. In response to this situation, an anti-urban strategy was implemented in order to keep people under control. This was achieved by promoting home-ownership outside of cities. The challenge was then to have the workers to travel to the cities for work purposes. Thus, in 1834, the national railway company was established. The dense railway network eased commuting for the working class between their homes “in the healthy countryside and the factories in the cities or the coal mines”7. Later, in 1869, the appearance of a social railway tariff further facilitated travelling. Complementing the railway network, the light railway network company was established in 1884: “Together, the two railway systems would form the densest system in any of the industrialising countries by the end of the 19th century”8. The engineer Pousset “challenged the radio-concentric pattern of the existing city system and replaced it by a network logic in which city and country were treated equally. Instead of connecting the rural villages to the nearest city, Pousset equipped them with a direct link to the national railway network”9. By the 1890s, more than two million workers commuted to work every day. To further promote single-family house, in 1889, the Housing Law was implemented. Under this law, cheap dwellings were constructed and the population benefited from tax exemptions and cheap social loans.

Interwar Period

After the First World War, during the Interwar period, the authorities’ motives to promote the single-family house shifted. The government wished to diminish the level of homelessness in the cities during the 1930’s economical crisis by encouraging the unemployed workers to stay in their countryside house and cultivate their gardens for food. During the Interwar period, a new policy was set up, one that is still in function today. To solve the poor conditions in which large families had to live, the large-family funding gave to the latter cheaper loans with decreasing rates for the purchase of a house11

Before the economical crisis “a mass culture developed in the towns during the 1920s, with modern department stores, cinemas and dance halls springing up for the general population”12. The KAV (catholic working-class women association), saw a threat in this new emancipated lifestyle, and thus used the single-family house as a tool to promote domestic life. To the KAV the mass society was linked to “egoism and loss of personality”13 and overcrowding. Following the war, the shortage of housing and bad living conditions brought

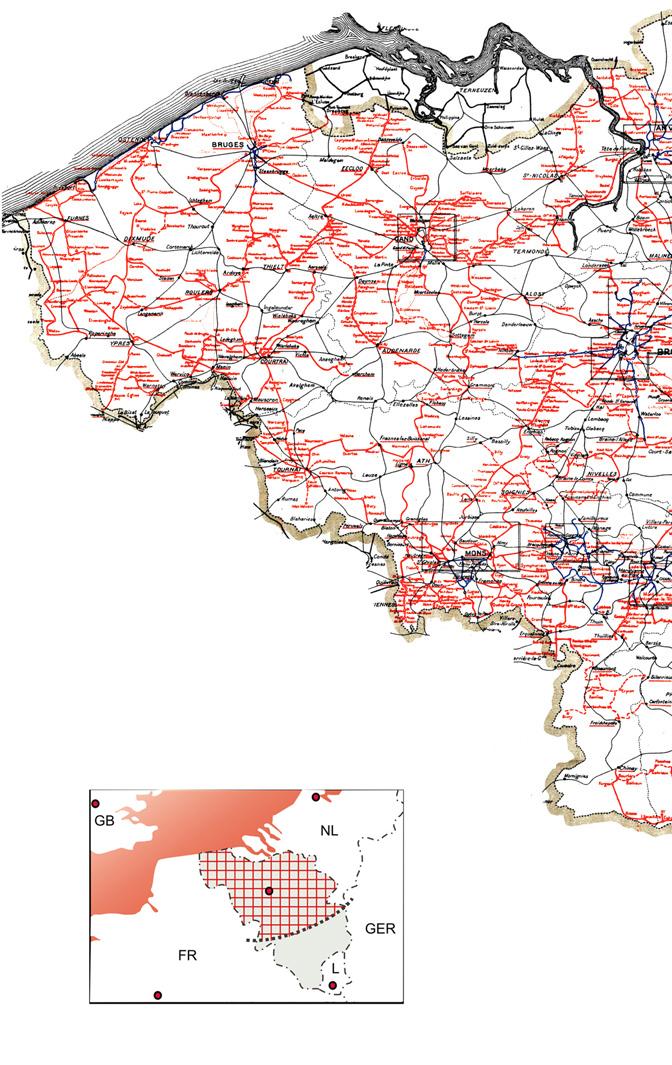

Fig. 3 “shows an almost homogeneous network in which city and village were relatively equally connected”10

Source: De Decker, P. (2010)

5, 6, 11 De Decker, Pascal, Facets of Housing Policies in Belgium, 2008

7. De Meulder et al., Patching up the Belgian Landscape, 1999

8. De Decker, Pascal,Understanding the Housing Sprawl, 2011

9, 10. Block, De Greet, and Janet Polasky, , 2011

12, 13. Caigny, Sofie De., Catholicism and the Domestic Sphere : Working- Class Women in Inter-War Flan

2016

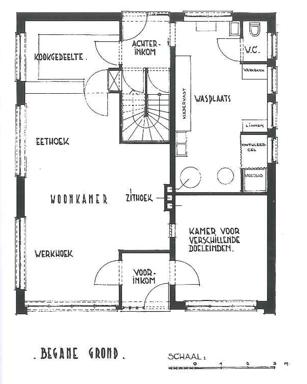

the KAV to establish in 1929 the Credit Association for Building Inexpensive Dwellings. In addition, KAV gave lessons and lectures to encourage rationality in dwelling and domestic life14. The KAV, which gained up to 125 000 members, organised in 1939 an exhibition entitled: “We are Building a New Home!” It was revolving once again around the promotion of the single-family house as the best housing option. They first exposed the bad reality of slums, and single room dwellings. Secondly, they illustrated why the single-family house was the best option for every workers. Thirdly, they showed the financial options for building their dream house. Fourthly, they promoted “do-ityourself ideas” by indicating how the families could save money by helping the construction of the house. Finally, the KAV also suggested furniture and programs for the different rooms. They fought against the socialist housings by defining that it is impossible to create a home “when having a ceiling under their feet and a floor above their ceiling”15. At the time, modernist, socialist and avant-garde currents rejected the idea of cosiness as it derived from the bourgeois culture. However, cosiness was part of the Catholic promotion speech as it reflected their values of interiority and privacy. The family had to live united in a cocoon inside the home.

Welfare State

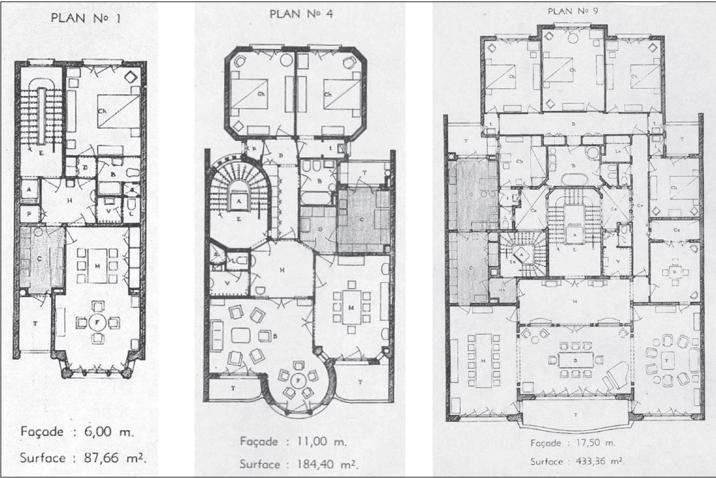

After the war, the welfare state set the basis for a system of healthcare, unemployment management, old age pensions, etc. Moreover, social infrastructures, cultural centres and sport facilities developed. At the time, a strong pillarization and division of the society was happening between the Catholics and the socialists. The Catholics, having more power and influence promoted the single-family house. It was a way to strengthen the catholic and family values that, according to them, were embedded in the single-family house model. An important difference between Catholics and socialists was that the latter focused on individuals and promoted rental apartments that gave their occupants more freedom to engage in social or political organisations (since they did not have to cultivate a garden or to bother about maintenance issues). Catholic associations on the other hand promoted home education and published books with model homes. They followed between 1950 and 1960 modernist ideas, but later became less strict. In the 1960’s, the associations supported a hybrid type of house characterized by a modern floor plan and being traditional in appearance. Consequent to the pillarization, the De Taeye grant system was introduced. As the Catholic party members were also part of the government, their power was undeniable. De Taeye grant was a Catholic act that gave free grants for families that became owners of a house through purchase or self-construction. The Act De Taeye encouraged private initiatives, not part of any governmental program, by setting up a mortgage system that allowed builders to borrow up to 90% of their property’s value. In the first five years, there were 100 000 beneficiaries. On their hand, the Socialist also established a law: the Brunfaut law, which promoted public housing, and which was much less successful. Although the two laws had diverging intentions, the population benefited from both acts combined: the social one for the developments of infrastructures and the catholic one for the houses.

Between the 1950’s and1960’s, a massive modernization of Belgian infrastructure was taking place. It included the 1954 Road Act, 1956-1965 Antwerp Ten

and 1957 Canal Act. These generated employment

ties led to a boom in the construction industry, enhancing urban sprawl, which often happened around industrial sites.

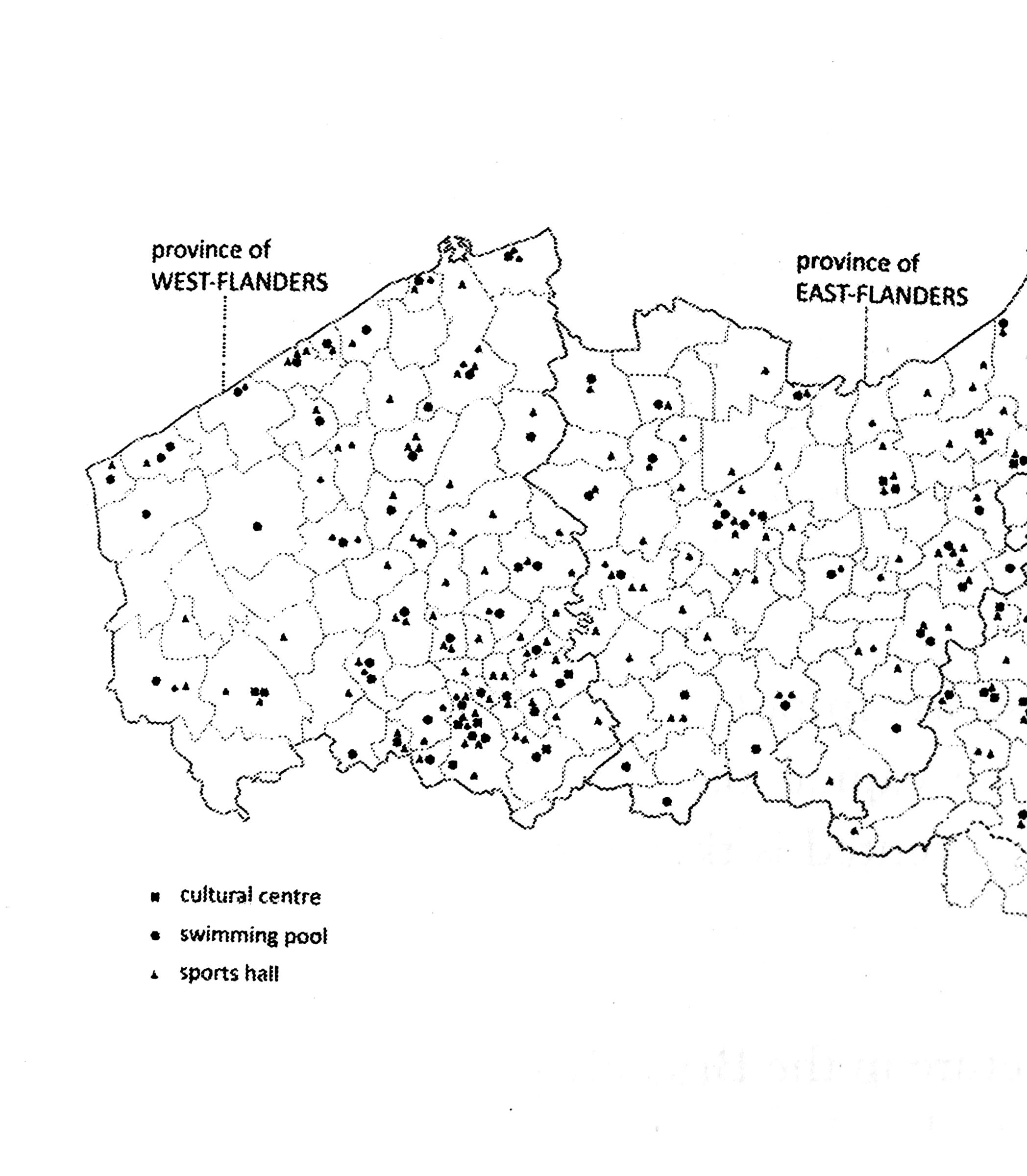

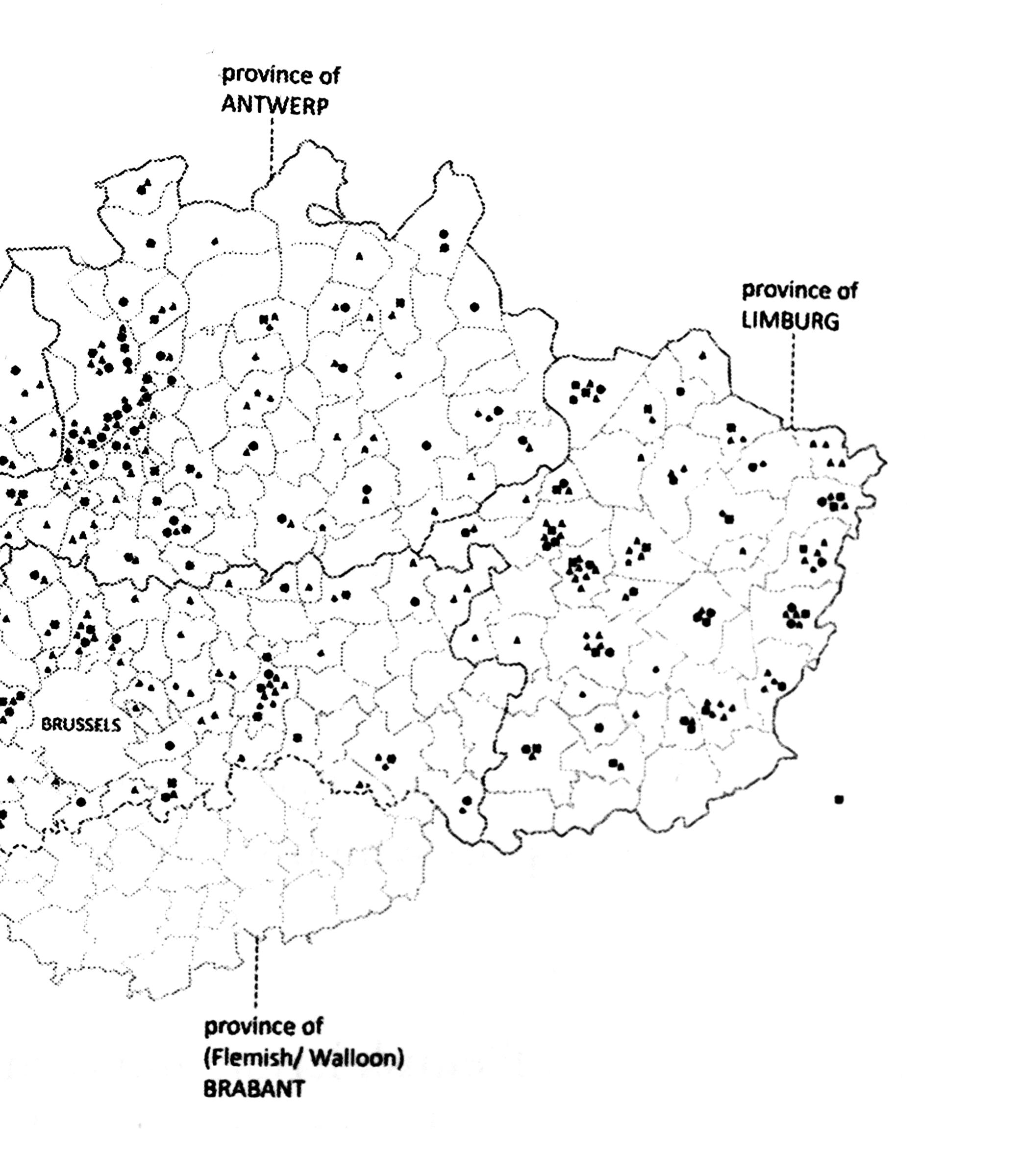

The 1960 implementation of two-day weekend for workers contributed to the development of leisure facilities, which facilitated the continuation of urban sprawl. Similarly to the light railway network, which was developed homogenously across Belgium, leisure infrastructures developed in a scattered and equal manner across Belgium – based rather on land cost and road accessibility than on urban proximity.

Urban sprawl in Belgium happened very easily since the industrial revolution due to the lack of planning laws that never slowed the process. Indeed, it is only in 1962 that a special planning law was introduced. However, the law was not effective until the end of the 1970’s, the post-war housing boom occurred without any planning nor allotment or construction permissions: “lots of reports, policy memoranda and popular media reportages have illustrated the lack of any alternative position for large-city neighbourhoods because of the densely built, poor-quality housing in areas with little greenery and open space”16

Today

Although urban sprawl is still increasing, the current reality of the single-family houses built during the previous eras is not as bright as this was originally promoted. The population living the old single-family houses of Flanders is ageing17, and the house and garden maintenance has become a chore. In Flanders, on average, 40% of the single-family houses are underused. This percentage even rises to 70% in some residential neighbourhoods over the entire region18. The old houses do not attract younger generations because they are too big for contemporary families as well as “out of style”19, being not fashionable for the contemporary-day trends. Furthermore, the old single-family houses are not energetically efficient. The installations are often old and consume a high amount of energy especially for the number of people living in the houses. One of the major problems is the lack of good housing alternatives. All the policies concerning housing in Belgium have always promoted the model of the single-family house located on the fringes of the cities. All other alternatives have always been ignored: “private renting was never seriously regulated and in periods of exuberant rent rises, this was never compensated by rent allowances”20. Although the government does acknowledge the problematic of sprawl and its many consequences, sprawl still seems to be unintentionally promoted. For example, “for some citizens, such as civil servants, commuting by public transport recently became free of charge, and almost all other commuters, even car users, can deduct their transport costs from their

Conclusion

Conceptualising the development of single-family house phenomenon, four evolution phases can be identified. The industrial revolution period can be considered as the “genesis” of the single-family house phenomenon. Initiated by Catholic elites, private ownership and the single-family house appeared as an efficient and necessary tool for controlling the masses. The “renaissance” of the trend can be associated with the interwar period. The single-family house concept at the time regained popularity by shifting from being simply a strategy to relief the cities to an ideology of salvation. The “climax” of the concept was reached during the welfare state. There was massive promotion, subsidizing and support from the government as well as from the Catholic parties. Living in a detached or semi-detached house in the suburbs became standard. Hence, a major question rises: how the current stage of the evolution of the single-family house phenomenon can be identified? Reflecting on this will certainly give us clues about the future of urban sprawl and how to tackle it. There is a clear discrepancy between the fact that religion and welfare ideologies are in a state of decline and that urban sprawl is still on a rise. Through looking at history, it is obvious that the catholic ideology has always been the driving force of urban sprawl. However, what has replaced it today? Has the single-family house become an innate and unquestionable concept of Belgian culture or has it become driven by another force such as individualism and consumerism – me, my house, my car. Is it possible to move towards different living possibilities and alternatives?

The government has started to take measures to counter sprawl; however, the latter are not efficient, such as the 1997 Ruimtelijk Structuurplan Vlaanderen, which still does not give any tangible results. (This regional master plan of Flanders was meant to protect the remaining countryside, limit the development of new infrastructures, densify and optimize existing urban areas). Not only there is a split between the continuous rise of the sprawl and the decline of catholic religion, there is also a gap between the governmental plans to slow sprawl and reality.

Possibly answers can be found by observing another contemporary issue –global urbanization. Belgium is often presumed to be a country with permanent immigration. Immigrants made up almost 18 percent of the entire population in 201022. People from all over the Europe and world settle in big cities seeking for better life conditions and opportunities. This process puts a lot of pressure on cities, creating a demand for housing and generating the densification. Considering the massive urbanization as an issue with several problems (disbalanced economy, ecological impact, poor quality of city environment), densification appears not as a solution but rather as a catalyst for same process. From this perspective, can shifting the focus on suburbia be a panacea for solving at once both issues: urban sprawl and massive city densification?

Considering the out-dated single-family houses and the settlements they form, the Belgian landscape is a place of high potential and challenges. Transformations of the existing context as well as the addition of new typologies in the existing suburbs can set up a new space organization and economy. Moving away from the idea of concentrating jobs and facilities in cities, suburbs can transform into places of life and production, becoming alternative to the dense city. The adaptation of suburbs for more diverse lifestyles can offer an

opportunity to live in a way that is better adapted to the contemporary/future population needs.

Additionally, as the welfare state is currently in global state of decline, it is logical to seek for new forms of ownership and ways of cohabitation in order to benefit from each other’s help, rather than waiting for the government’s solutions. Living within small communities and sharing facilities and tasks can ease and make more accessible for middle class population to own a good quality housing in the future.

The chaotic Belgian landscape presents a complex many-layered task to solve. The difficult nature of the problem requires a multidisciplinary approach, which would foregather economical, historical, analytical, cultural and urban components. However, according to Sun Tzu23. “In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity”. For sure, there is a great opportunity when you deal with the “ugliest country in the world”.

Bibliography

Avermaete, T. (2006). Wonen in welvaart woningbouw en wooncultuur in Vlaanderen, 1948-1973/ Living in wel fare housing and living culture in Flanders. CVAa, Antwerp

De Decker, P. (2010). Understanding housing sprawl: the case of Flanders, Belgium. Environment and Planning A 2011, volume 43, pp.1634-1654

Decker, Pascal De. 2008. “Facets of Housing and Housing Policies in Belgium,” 155–71. doi:10.1007/s10901008-9110-4.

De Meulder, B. et al. (1999). Patching up the Belgian Landscape. Oase: tijdschrift voor architectuur, 52: 78-113.

De Caigny, S. (2005). Catholicism and the domestic sphere: working-class women in inter-war Flanders. Home Cultures, 2 (1): 1-24.

Gosseye, J., and Heynen, H. (2010). Designing the Belgian welfare state 1950s to 1970s: social reform, leisure and ideological adherence. Journal of Architecture, 15 (5): 557-585.

Heynen, H., and Van Caudenberg, A. (2004). The rational kitchen in the interwar period in Belgium: discourses and realities. Home Cultures, 1 (1): 23-50.

Polasky J., Block G. (2011) Light Railways and the Rural-Urban Continuum: Space and Society in the Late Nine teenth Century Belgium,.

Ryckewaert, M. (2011). Building the economic backbone of the Belgian welfare state: infrastructure, planning and architecture 1945-1973’. 010, Rotterdam

Ryckewaert M., De Meulder B. (2012). Ribbons and patches Mapping suburbanization patterns in Belgium,AAG Annual Meeting,New York

https://rsv.ruimtevlaanderen.be/