43 minute read

Market Watch

Watch

Carryforward Almost Gone As PB, Snacks Feed Families In Quarantine

J. Tyron Spearman Contributing Editor, e Peanut Grower

Stress in agriculture has never been greater. Two major hurricanes, Irma and Michael, quality problems and now germination issues, low commodity prices, COVID-19 pandemic, riots and unrest in cities, talk of food shortages, a devastating court ruling on a popular chemical product...the list seems endless.

The U.S. peanut market has remained quiet during the COVID-19 pandemic. There has been no panic in prices. The increase in prices for raw-shelled peanuts was caused mostly because of quality issues from the 2019 crop. Aflatoxin reared its ugly head and clean, top-quality raw-shelled peanuts became a premium.

Shellers and production facilities set up COVID-19 precautions and kept delivering while protecting their employees. With consumers concerned about a food shortage, the peanut industry provided grocery stores and other food outlets with the peanut products they want and need. The American peanut industry takes the responsibility of producing quality food products very seriously. The nation’s leading health, food and agriculture agencies were also working with industry to ensure a safe and stable food supply.

USDA Help

Congress and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, through the Farm Service Agency, started accepting applications from agricultural producers who have suffered losses. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act allocated $16 billion to provide vital financial assistance to producers of agricultural commodities who suffered a 5% or greater price decline due to COVID-19. Peanuts did not have a 5% or greater loss.

Other programs available included the Paycheck Protection Program and Leading Marketing Indicators (June 3, 2020)

2020 Acreage Est. (+7%) ...................................................1,468,000,acres 2020 Production Est. (4,000 lbs/A) ..................................... 2,936,000 tons 2019 Acreage (+ 1%) .........................................................1,391,000 acres 2019 Production (3,949 lbs/A) ............................................ 2,748,043 tons 2019 Market Loan ............................................................... 2,341,062 tons

2019 Remaining in Loan ........................................................ 945,973 tons 2019-20 Domestic Usage (9 Mo.) ........................................... Up + 5.5 % 2019-20 Exports (8 Mo.) ........................................................... Up + 25.3%

POSTED PRICE (per ton) Runners -$424.13; Spanish - $416.70; Valencia and Virginias - $430.94

the Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program, which was mainly for farmers with storm or drought losses.

Acreage Estimate And Production

U.S. peanut production is forecast at 5.9 billion pounds (2,935,000 tons), up from 5.5 billion pounds in the 2019-2020 marketing year. Planted acreage intentions were up 7% to 1.5 million acres with the largest increase in Georgia. Some estimate that acreage could be up 15% to 20%. Seed germination on later-shelled lots has been reported as problematic.

The U.S. average yield is projected to increase by 1% to 4,000 pounds per acre. Based on the peanut supply and slightly increased use, the carryforward is now estimated at 11% less or 828,000 farmer stock tons.

Contract Offers

Farmers wanted more than the $400 to $425 per ton for runners and $450 per ton on Virginias with shelled market prices at 45 cents per pound. Prices for cotton or corn were not exciting enough to be in competition for peanut acres. Most farmer stock contracts were signed when raw-shelled prices jumped to 80 cents per pound. Farmers are hoping for a price improvement on uncontracted 2019 loan peanuts and 2020 uncontracted stocks. Offers will likely be impacted by the acreage report issued by USDA on June 30.

PLC Payment

Per USDA, the average price received by farmers for farmer stock peanuts averaged 20.6 cents per pound or $412 per ton in March. Prices in February were slightly lower at 20.5 cents per pound or $410 per ton. Prices have been the lowest in history this year with a low of $384 per ton in November to a high of $418 per ton in January. The ninemonth average is about $404 per ton. Farmers who signed up for the Price Loss Coverage program will receive a payment in October, the difference between the average price, now at $404, and the reference price of $535 per ton or $131

Watch

per ton. The preliminary estimate from USDA is $125 per ton. This price would be applied to 85% of the peanut base tons on the farm.

U.S. Peanut Usage

Use of raw-shelled peanuts in primary products in April 2020 was led by peanut butter up 12% versus April 2019 and up 5.5% for the year. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic’s call for families to stay at home has many grocery stores asking for more peanut butter. The pandemic has led to more snacking, up 9.2% for the month and now up 5.4% for the year. Government purchases for nutrition programs in April totaled 1.173 million pounds of peanut butter, down 330% compared to same month last year. However, for the 9 months, government purchases are up 2.6% to 18.6 million pounds. Overall, usage is up 4%.

Export Peanut Usage

U.S. peanut exports are up 25.3% over an eight-month period and up 33% comparing March 2020 and 2019. In-shell peanut shipments to China totaled 5,939 metric tons in March and 61,000 metric tons for the year. China is also buying raw-shelled peanuts, ranking third in shipments behind Canada and Mexico. Raw-shelled exports are up 4%, but peanut butter is down 9.4%.

Argentina is almost complete with peanut harvest estimated at 1.26 million metric tons. Officials report that quality is good, and yield should be 3,300 to 3,500 kilograms per hectare. Acreage is about 10% less than last season, and sound mature kernels are reduced likely because of smut.

In Brazil, production, distributed between the first and second crop, is estimated at 557,300 tons, 28.2% more than the last crop. With ethanol in crisis, sugarcane has given ground to peanuts.

Current Market

The market today is at a standstill as demand is quiet for the time being. It appears that manufacturers are watching demand trends and are worried to put on more bookings for late summer in case demand slides.

Peanut butter companies are aware of consumption increases but don’t know how long it will last. They are taking a wait-and-see attitude. Raw goods are still priced in the low- to mi- 80s. Europe is in a similar situation as both Brazil and Argentina are offering into the European Union market, but buyers are quiet for the same reasons. Officials are concerned about logistic problems in Brazil as the COVID virus is widespread and will affect shelling plants and moving goods to the port.

What Now?

More than 70% of producers are worried to some degree about coronavirus’ impact on their farm’s profitability. Over 60% said they expect farmers’ equity positions to decline over the next year.

Producers hope for a better quality crop in 2020. ‘‘ As the economy returns to a new normal, sales of peanut butter and peanut products should be at an all-time high. Good news for everyone is that the old 2019 crop and the large carryforward are about gone.

As the economy returns to a new normal, sales of peanut butter and peanut products should be at an all-time high. Good news for everyone is that the old 2019 crop and the large carryforward are about gone. Stay healthy and safe, and have a good season. PG

Southeast Climate Outlook

By Pam Knox, University Of Georgia Weather Network And Agricultural Climatologist

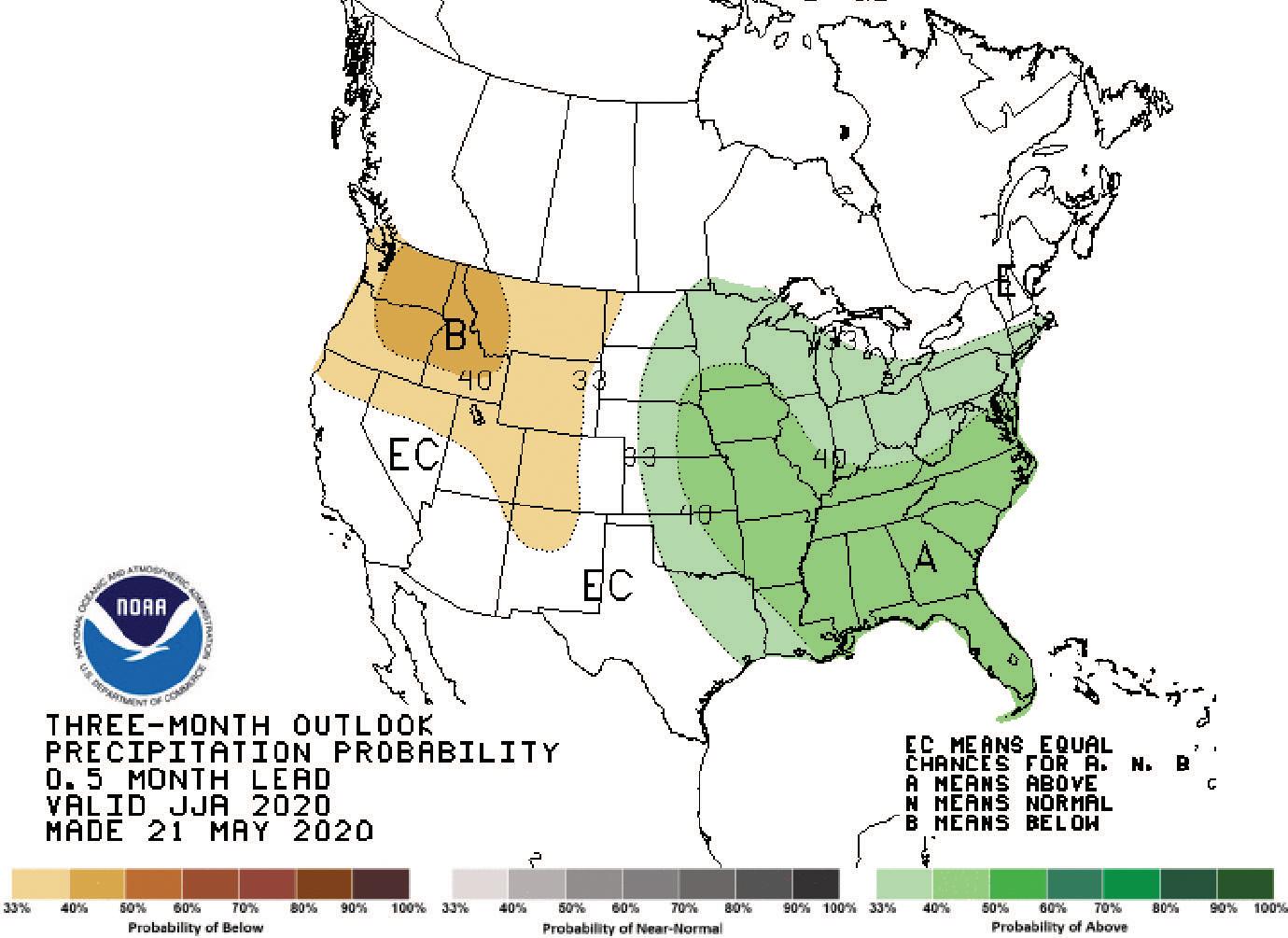

Now that June 1 has passed, we are in climatological summer and also in the official Atlantic tropical season. What can we expect for the rest of this growing season and into the fall harvest period?

The major factors to consider for this year are the long-term climate trends and the status of El Niño/La Niña, which will affect the Atlantic tropical season. Average temperature since the 1960s has risen across the Southeast by about 3 degrees Fahrenheit; daytime high temperatures have risen by about 2 degrees F, while nighttime minimum temperatures have increased by about 4 degrees F. The rise in nighttime temperatures is mainly attributed to increases in humidity.

Precipitation has not changed much over that same period while there have been yearly variations.

A Tropical Shift

Over the past few months, we have been in ENSO-neutral conditions and on the warm side of neutral. In the last month, we have seen a swing toward La Niña, and I expect that by the end of summer that’s where we will be. La Niñas are associated with active Atlantic tropical seasons due to lack of vertical wind shear.

Based on those trends, I expect the summer to be warmer than normal across the region and wetter than normal, particularly along the Gulf Coast. Increased humidity is likely, especially overnight. Fall is also expected to be warmer than normal, but there are no clear signals in precipitation, except in the Florida Peninsula, which is expected to be wetter than normal.

A Dry Fall

Predictions of the number of Atlantic named storms this year uniformly indicate that we will see more storms than usual. Keep in mind, an active season does not necessarily bring more rain to the Southeast. Last year was well above normal in the number of storms, but there were only two that affected Georgia.

Since the Gulf of Mexico is quite warm, it means there is a potential for more rapid intensification of Gulf storms than usual. Because storms could develop quickly, watch weather forecasts carefully when planning fieldwork and harvest.

If La Niña develops quickly, there is a chance for dry conditions in the fall. What happens at your location will depend on where the tropical storms go this year.

Climate updates are posted to my blog at https://site.extension.uga.edu/ climate, on Facebook at SEAgClimate, on Twitter at @SE_AgClimate or email me at pknox@uga.edu. PG

What Can We Expect:

• Neutral conditions are expected to change to La Niña by fall. • An active Atlantic hurricane season is planned. • Long-term trend is toward higher temperatures and humidity, especially at night. • Warmer and wetter conditions likely across Southeast summer, especially near the Gulf Coast, with warmer-than-normal temperatures continuing through fall. • Some potential for dry conditions in fall if La Niña develops.

Ready, Set, Go!

Reduce digging losses with proper setup and field checks.

By Amanda Huber

Once the decision to dig has been made and equipment is readied and pulled into the field, a quick field test is needed to put the final adjustments into place.

Clemson University agricultural engineer Kendall Kirk says that producers should synchronize the speed of their digger’s shaker chain, or conveyor belt, to their ground speed. If driving 2 mph, for example, the conveyor belt should be set to a speed of around 2 mph.

“Slower speeds should be used where digging losses are more likely, such as with larger pods, suboptimal maturity, heavier soils and drier soils,” Kirk says. “Driving too slowly will reduce your ability to dig on a timely basis; driving too fast can cause higher yield losses.”

Vine Growth Affects Speeds

Research conducted in 2016 by Kirk and others at Clemson found that digging losses for 80% to 110% of conveyor speed as a percent of travel speed were similar in both Amadas and KMC diggers in Virginia-type peanuts. Digging losses increased by 100 to 200 pounds per acre when conveyor speed was equal to 120% of travel speed.

In 2017, it was found that optimum conveyor speeds of 85% for both equipment brands in Virginias, with significant reductions in yield at higher conveyor speeds tested of 100%, 115% and 130%. Similar tests in runner-type peanuts suggested that optimum conveyor speeds for the KMC digger were 100% to 115%, with at least a 350 pounds per-acre loss in yield digging at 70%, 85% or 130%.

Kirk says the results suggest that lagging the conveyor slightly in excessive

vine growth of Virginia-type peanuts, particularly, may be beneficial.

Field Testing Conveyor Speed

According to Kirk, a simple way to set the conveyor speed to match ground speed is to adjust it until the inverted windrow falls slightly, about 2 feet, down field from where the plants were growing. This can be assessed by placing a flag outside of the digger path at the beginning of a row and observing the location of the end of the windrow relative to the flag.

The check works best if the digger is engaged at full operating speed prior to entering into the peanuts. If the end of the windrow is several feet farther into the field than the flag, then the conveyor speed is lagging. If the end of the windrow is equal in position to or behind the flag, then the conveyor is faster than the ground speed.

Look For An Even, Smooth Vine Flow

Producers’ best resource in digger set up and operation is the owner’s manual that comes with the equipment.

The KMC operation guide offers the following guidelines on set up and operating speed.

“Adjust hydraulic speed to match with miles per hour of the tractor or as needed to allow for even and smooth flow of peanut vines up the conveyor. Make

a partial pass in the field, then turn off machine and tractor or have someone following from behind to monitor machine performance.

“Check to be sure minimal peanut loss is found on the surface or down in the ground. Look at the inverted windrow to ensure that the tap roots are standing straight up in the air and not leaning to one side after inverting. If peanut vines are not inverting with the tap root up, adjust the vine rods to make a tighter windrow, and be sure that the cutting coulters are deep enough to fully cut the peanut vines.”

KMC says the proper speed of the conveyor can be adjusted by using the provided rear shaft tachometer readout and adjusting the hydraulic flow so that the readout shows 2.9 for a 3 mph tractor speed. The tachometer is programmed from the factory to give the correct readout for the speed relationship of 3 mph tractor speed, the normal operating speed.

Daily Checks For Machinery

Each day of digging should begin with a careful examination of the equipment. Amadas’ operator manual advises inspecting the following digger parts.

“The conveyor belt assembly, drive chain and conveyor rods are a part of the digger-inverter that needs to be checked daily. Inspect conveyor rods for damage. Check for bent pins or rods. Repair or replace as needed.

“Inspect the conveyor belts’ tension and tracking. The belts should have approximately 2¼ inches of sag. Inspect the conveyor drive chain daily for signs of wear. Make sure the chain is properly aligned and with the correct amount of tension. Repair or replace a damaged chain as needed.

“Inspect the inverter drive chains daily for signs of wear. Make sure the chains are properly aligned and have the correct amount of tension. Repair or replace a damaged chain as needed.

“Inspect inverter rods daily for visible damage. Adjust rods if out of alignment. Replace or repair rods as needed.

“Scrapers are located at the bottom of each conveyor belt. Make sure each scraper is securely in place. Keep scrapers free from debris to ensure proper conveyor operation. As the scraper blades wear, it is important to adjust the placement of the scrapers to keep them close

Inspect and adjust digger and sharpen blades. Set the blades with a slight pitch to cut the taproot just below the pods. Ensure uniform, fluffy, well-aerated windrows. Pods should not touch the ground. Carefully adjust combine for your field conditions. Read your operator’s manual for specific adjustments. Proper combine adjustment and speed will reduce pickup losses, percent of loose-shelled kernels, hull damage and foreign material. Excessive dirt and trash blown into the basket during combining will cause airflow restrictions during the curing process and may result in uneven drying and mold development. Combine efficiency depends upon several variables including windrow condition, cylinder speed, forward travel speed, internal adjustments and modifications for large-seeded peanuts. Impact and mechanical injury during harvest is largely associated with fast moving parts of the picking cylinder. Speed can be the enemy of peanut quality. Fast-moving combine parts may damage a high percentage of hulls and kernels. Both visible and non-visible damage opens the door to insect and mold infestations. Read more of the U.S. peanut industry’s Good Agricultural Practices on the American Peanut Council website at https://www.peanutsusa.com/good-manage ment-practices.

to the front idlers (1/16 inches) to prevent soil build up.

“Excessive build up on the front idlers will over-tension the conveyor belt and cause premature wear. Note that an excessively worn blade may be flipped so that the other side can be used.”

See the operator’s manual for additional daily and weekly checks.

Conveyor Speed Calculator

Current models of Amadas and KMC diggers provide an interface with a digital readout of the conveyor speed in miles per hour so that hydraulic flow rate can be easily adjusted to match conveyor speed to travel speed.

In absence of a digital readout, Clemson University’s precision ag team created a conveyor speed calculator. Through simple calculations and set up, producers can use this method to set conveyor speed relative to ground speed. The tool can be found at http://precisionag.sites.clem son.edu/Calculators/PeanutDigger/ ConveyorSpeed/.

Reduce pod loss and add to the bottom line with careful setup and testing of harvesting equipment. PG

A Weighty Decision

Dig at optimum maturity with the aid of a profile board.

By Amanda Huber

Determining when to dig is always tough. The maturity profile board, developed in 1981 by E.J. Williams and J.S. Drexler, ushered in a new era of determining how close to ready a crop was without special equipment and the destruction of the pods.

Auburn University assistant Extension professor Kris Balkcom says, “The peanut maturity profile board is a tool that helps you get an average look at what kind of crop has been set and helps determine optimum digging.” The profile board works

Performing A Maturity Profile Board Check: • The sample must be a good representation of the field to get an because as peanuts mature, the mesocarp color changes from white to yellow, orange, brow n a nd t hen black . Although kernels in pods accurate recommenwith an orange mesocarp are dation for digging. mature enough to be consid• Pull a field sample ered sound mature kernels, and check it against they continue to increase in the profile maturity board at least twice. Two checks offer more assurance that you are on target for a proper both yield and grade by adding weight as they grow. To use the profile board, producers expose the mesodigging date. carp using a pressure washer. “A pressure washer in the range of 1200 to 1600 psi is sufficient,” Balkcom says. “You don’t need a bigger one. The smaller ones do a good job and keep from busting up the pods, including the immature ones.”

Start With A Good Sample

The key to getting an accurate reading on the profile board depends on getting a good sample.

“Pluck up a small bunch of peanuts from different locations across the field. Pick plants that are uniform and free of disease. Disease would affect the sample,” he says.

“Look at the pods and make sure they don’t show symptoms of disease. There could be pod rot or underneath white mold. You want to look at those pods to make sure they are good and healthy and that will give you a good sample reading.”

Balkcom also says to look at the foliage and the condition of the vines and stems.

“You want to see that the plants are in good shape and will

hold onto those pods.”

When you have all the samples gathered, pick off all the harvestable pods from the plant, including fully formed pods and immatures.

“Pick off all the pods that would go into the combine basket if being picked. Continue until you have got a good uniform sample of about 200 pods. That’s the sample size you need. Like soil sampling, the goal is to get a good average,” he says.

Blast Hull To Show Mesocarp

At that point, the sample goes into a wire mesh basket, and using the pressure washer, the outer layer is blasted off.

“Do not place the nozzle too close to the pods because it could disintegrate the more immature pods. As you begin to wash and spray the outer hull and expose the mesocarp, you can see the different color underneath.”

Once you are satisfied that the hulls of the sample have been separated and the mesocarp underneath exposed, the

sample is ready for grouping into colors.

“On the board, pods are placed light to dark with lighter ones being less mature and darker ones more mature.”

Shell Pods To Expose Kernel

Once the pods are separated by color, Balkcom says some peanuts grouped in the darker area should be shelled so you can see what is happening with the kernel.

“Pods that are completely mature have a nearly black or black hull and the seed coat is tan or copper colored. Those pods would be placed in the three days to harvest category.

“The next group would have a seed coat that is a lighter color, but with dark oil spots formed on the surface as the peanut gets closer to maturity. The oil content increases in the kernel and comes to the surface. When you see the darkened oil spots, that generally means it is about seven days away from maturity. At 10 days, oil spots are not as distinctive as they are at seven days.”

Balkcom says many of the hulls will be dark, which is why shelling them is necessary.

“You need to take a look at what’s going on inside and look for those oil spots as a tell-tale sign of maturity progress.”

Take Two Samples For Certainty

Other scenarios producers may see are where one kernel has the copper-tinged seed coat but the other has the oil spots.

“With one fully mature and the other needing a few days to bring it along, we would put that in the three- to five-day range,” he says.

When you end up with two distinct groups on the board, it is likely because there was a drought in the mid-season. This type arrangement presents some challenges, Balkcom says. “The risk in waiting on the crop to mature further is losing those pods that are already mature.”

To get a more accurate picture of digging date, producers should pull samples and perform the profile maturity board check at least twice. The first time should be when it is estimated that the crop is about 10 days from digging. The second check would be when the first sample said to dig.

“Two checks will give you a better chance to get the top dollar for your crop,” Balkcom says. “It’s very important when you think about selling by the ton on the grade and you get more money per point. It adds up.”

Maturity profile boards are available at county Extension offices, buying points or product sales representatives. PG

NCSU Offers Updated Peanut Maturity Board

North Carolina State University Cooperative Extension recently released an updated maturity profile board for Viriginia market type peanuts. It will be available through Extension offices.

NCSU Extension peanut specialist David Jordan says, “We included some images of things you might see in your crop on the profile board. The goal is to make it a better management tool and to help identify potential problems to avoid in the field.”

For many years, the North Carolina Peanut Growers Association has supported NCSU research and Extension efforts that have contributed to the information provided on the peanut profile board.

A TRIBUTE TO DR. BARBARA SHEW NCSU Research And Extension Plant Pathologist

A Voice Of Accuracy And Precision

David Jordan T his fall, Dr. Barbara Shew will retire after many years of contributions to the peanut industry. Her work has encompassed the core components of the land-grant system — Extension, research and teaching — and in doing so, she has touched the lives of many people.

We are all very appreciative of her presence in the field, classroom, in front of an audience of peanut growers, around a table of eastern North Carolina seafood or barbeque, and in more formal settings such as the annual meeting of the American Peanut Research and Education Society and the American Phytopathological Society. In each of these settings, Barbara conveys a clear message of support and appreciation for the people in front of her with an eye toward helping someone else be successful. In helping others, Barbara has been very successful in her role in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology.

Clear Message Of Support

I personally have gained much from Barbara’s presence and integrity as a person and a scientist. Those who have been around me know that my organizational skills are not the best and are somewhat lacking. My field maps have been found on the bottom of paper plates, and I have been known to write down important data on a truck tool box or tailgate, a plot stake or on yellow flags that have been sitting in the field all year. I think I remember the results of a trial, only to find that the summary in my head and the words to express it weren’t quite right. My peanut-breeding friends

would cringe at my stack of plot plans and notes for the year held together by a single clip.

My point is not to dwell on my limitations but to contrast them with a skilled and effective scientist — Dr. Barbara Shew. Often times, the words accurate and precise are contrasted, and on many occasions, students in prelims are asked to state which of these is more important. With Barbara, people in our industry have witnessed someone that is both accurate and precise in her work and in her words. Both of these matter.

An Example Of Integrity

Clearly presenting both the strengths and limitations of her research findings and their application are what peanut farmers and those who support them need. We work in a landscape that can vary from field to field, day to day and certainly year to year. When combined with people’s personalities and views, what helps farmers the most is a clear message that is as accurate and as precise as possible. At times, I find myself telling someone what they want to hear (in most cases after trying twice to tell them what they really do need to hear.)

Barbara does not fall into that trap, and she has always stayed the course on what she knows in her recommendations. This applies not only to plant pathology but also to life. We have all gained from her integrity and rigor.

Barbara, we will truly miss both your presence and your message. You have taught us much about how to work with people and peanuts in ways that bring out the best in both. We wish you all the best in your next phase of life after North Carolina State University. PG

— DAVID JORDAN

North Carolina State University Extension peanut specialist

Tributes To Dr. Barbara Shew

Peanut growers must find answers to many problems that arise in peanut fields. When it came to diseases, they knew that they could get help from their Extension agent. Dr. Shew worked with dedication to make sure findings from her research were transferred quickly to agents and consultants. Whether through the agent or in person, Dr. Shew brought NCSU and the College of Ag and Life Sciences to the farm. Thank you, Barbara, for all of your work. We will miss you.

— BOB SUTTER

North Carolina Peanut Growers executive secretary

◆ ◆ ◆

My observations are that Barb has always exhibited many admirable qualities. Maybe I just noticed them because they are ones that I battle. These include being highly organized, highly focused and her attention to detail. Barb always sought to provide solid answers in her research and to provide that information to growers in a timely manner and in a format that can be adapted to most any farming situation.

For many years, she has worked diligently with little fanfare and provided outstanding disease management programs for growers in North Carolina and beyond. Her collaborative spirit, deep desire to serve peanut growers and the entire industry as well as her mentoring role of younger female faculty in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology have been invaluable.

Barb will indeed leave a legacy of integrity and putting others first. We will miss Barb for reasons far beyond her peanut pathology expertise. Best wishes.

— RICK BRANDENBURG

NCSU Extension entomologist and longtime colleague

◆ ◆ ◆

Barbara is an outstanding scientist dedicated to the proposition that we should seek the truth and preach it. I certainly appreciate her abilities and accomplishments, but even more appreciate her spirit, always willing to help any way she can. She has certainly helped and encouraged me. Barbara has a brilliant mind, paragonal character, a big heart and a keen sense of humor.

— ALBERT CULBREATH

University of Georgia research pathologist

Collecting Samples

Learn how to properly collect soil and root samples to test for nematodes.

Nationwide, crop losses caused by nematodes are estimated at around 5% to 10% annually. In the Southeast, where environmental conditions favor growth and reproduction of nematodes, losses are even higher. The seven most damaging nematode species that affect Alabama growers are soybean cyst, lesion, stunt, lance, reniform, southern and peanut root-knot nematodes.

Symptoms caused by nematodes are usually not specific enough to permit diagnosis by examination of infected plants. Chlorosis (yellowing), stunting, early wilting and reduced yields are all frequently associated with nematode injury but also may be caused by other factors. Accurate diagnosis of nematode-induced disease or injury usually requires soil laboratory analysis. Before valid control recommendations can be given, the specific types and numbers of nematodes present must be determined. This requires proper collection of soil and root samples representative of the problem area.

When To Sample

Research at Auburn University shows that generally the best time to sample fields for nematodes is August through October. During this period,

Recommended Sampling Period soil nematode pop

Peanuts ............................................ August Corn .............................. August - October ulations are at their highest level and are

Cotton ................. September - October most easily detected.

Soybeans .......... September - October The worst time

Tomatoes ................... June - September to sample for nema

Potatoes ............................. May – August todes is in late winter through early spring. Nematode populations are at their lowest level during this period and may not be detected in the sample.

Where And How To Sample

Fields where crops have been grown repeatedly should be tested every two to three years for nematodes. In this way, a population of destructive nematodes may be detected prior to crop losses. This is particularly true where crop rotation is not practiced. For sampling, fields should be divided into 5- to 10-acre sections. Collect 20 or more random samples of soil from each section. Take samples from the top 8 to 10 inches of soil using a soil probe or shovel. Soil should be taken directly from the root zone if plants are still present. Mix samples thoroughly and remove one pint for the laboratory analysis. Do not collect samples when soil is dry or extremely wet, since nematode populations are usually low under these conditions.

When problem areas are present in the field, samples should be taken to determine if nematodes are the cause. Samples of moderately affected plants should be taken since nematode numbers are usually reduced beneath severely injured or dead plants. Samples should consist of roots and soil from several plants. Also, it is always a good idea to sample from an area where plants are unaffected. Keep samples separate and mark them “good area” and “bad area.”

Package And Send

Soil samples should be placed in a plastic bag, sealed tightly to prevent drying and placed in a nematode sampling carton. Sample cartons are available from county Extension offices. Sample number and origin should be recorded on each carton. If samples are not mailed immediately, store at 40 degrees Fahrenheit (refrigerate). Avoid placing the sample in the sun or in a closed automobile. Samples stored under such adverse conditions can give inaccurate results.

Label And Mail

Keep written records of the number and origin of each sample. In order to make a useful recommendation, information on the previous crop history and crop to be planted is needed. This information, along with the name and address where lab results are to be sent, can be placed on the Information Sheet for Nematode Soil Samples (Form ANR-F7). Mail samples to the appropriate plant diagnostic laboratory and include the sample service charge as needed. PG

The decision of whether to spray or not or when to start digging is not always an easy one. The decision is made more difficult when a storm or bad weather is predicted. Last year’s active hurricane season made end-of-season planning and execution tricky. Based on early season conditions and in case harvest conditions are similar to last year, Clemson University peanut specialist Dan Anco has the following advice. Changing Planting Dates Rains over several weeks in May caused some plans to change. Rain brought on late leaf spot to volunteer peanuts. Early pressure calls for early action. As we entered June, there was still time to get peanuts planted and obtain a reasonable window of conditions for growth and harvesting. Mid-May is generally the best time to plant peanuts in South Carolina, although peanuts can still be made if planted into early June. Once planting dates reach June 10, we are looking at approximate digging dates near Oct. 20 for a 132-day variety like Bailey or digging dates entering into November for moderate-maturity varieties like Georgia 06G. One of the concerns around that time of year becomes slow drying conditions prior to combining that can lead to quality issues if they sit out in damp conditions too long. Every year is a little different, but overall the combination of lower yield potential, higher late leaf spot pressure and generally unfavorable harvesting conditions are more prevalent for peanuts planted after about June 10. Risk Factors For Late Leaf Spot • Short rotations (less than 2 years out of peanuts) • Highly susceptible variety (Virginia types, Georgia 13M, Spain, TUFRunner 511) • Late planting (May 26 or later) • Poor control of volunteer peanuts in rotational crops • Poor end of season control of late leaf spot in an adjacent upwind field the previous year • Starting fungicide programs any later than 45 DAP; better early than late • Extending spray intervals beyond 15 days • Repeated, frequent periods of leaf wetness; excessive rains, frequent irrigation • Rain immediately after application – wait 24 hours to irrigate • Consecutive use of fungicides with the same mode of action (except chlorothalonil) Slowing A Growing Leaf Spot Epidemic: Effective fungicide programs are designed to prevent disease, not cure it after the fact. If something goes wrong and you find late leaf spot lesions in the bottom of the canopy, especially with less than 30 days until harvest, treat immediately, retreating in 10 days, with one of the following: • Topsin 4.5 FL 10 fl oz + 1.5 pt Bravo • Provost Opti 10.7 oz + 1.5 pt Bravo • Priaxor 8 fl oz pearman ad 11/14/08 3:19 PM Page 1 Three-Cornered Alfalfa Hopper Three-cornered alfalfa hoppers are light green and wedgeshaped. They stand about ¼ inch high and are about ¼ inch long. Both adults and nymphs have piercing mouthparts and feed by penetrating the stem and sucking plant juices. They tend to feed in a circular fashion around a stem, making feeding punctures as they go. The damaged area typically swells and above ground root growth may occur. On peanuts, feeding may occur on limbs, leaf petioles or pegs. Danitol Diamond EC Comite/Omite Warrior II Lannate Lorsban 4E Chlorpyrifos 15G Orthene Radiant SC Sevin Steward Thimet 20G Blackhawk Dimilin Intrepid Prevathon P/F NL NL NL G NL G/E NL G G E G NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL E NL NL G E F G NL G NL NL G G NL NL F/G G F/G G/E NL G/E G NL G G NL P/F NL NL F G NL G NL NL E/G E NL NL G/E NL G/E NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL F NL NL NL NL NL NL P NL F/G P/F NL NL P/F G NL NL NL G F/G E E/G NL NL NL NL G F/G NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL G/E NL G NL NL NL NL F NL NL G/E NL P NL G/E NL NL NL NL E NL NL E G G NL NL E G/E E E/G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL F/G F/G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL E/G Edited by Dr. Mark Abney, University of Georgia Extension Entomologist E = Excellent Control; G = Good Control; F = Fair Control; P = Poor Control; NL = Not Labeled; LS = Labeled for suppression only 1 Dipel and others; * Insufficient data Burrower Bug Burrower bugs can be hard to identify in the field and an infestation is often not detected until harvest. Burrower bugs have a black-tobrown body, small red eyes on a small-sized head. The upper wings of burrower bugs are shiny and semi-hardened with the membranous tip overlapping. Its legs are spiny, and needle-like, piercing, sucking mouth parts are visible with a hand lens. Burrower bug is closely related to stink bugs. Navigating The Late Season What are the factors affecting final sprays and digging decisions? Three-Cornered Alfalfa Hopper Three-cornered alfalfa hoppers are light green and wedgeshaped. They stand about ¼ inch high and are about ¼ inch long. Both adults and nymphs have piercing mouthparts and feed by penetrating the stem and sucking plant juices. They tend to feed in a circular fashion around a stem, making feeding punctures as they go. The damaged area typically swells and above ground root growth may occur. On peanuts, feeding may occur on limbs, leaf petioles or pegs. Danitol Diamond EC Comite/Omite Warrior II Lannate Lorsban 4E Chlorpyrifos 15G Orthene Radiant SC Sevin Steward Thimet 20G Blackhawk Dimilin Intrepid Prevathon P/F NL NL NL G NL G/E NL G G E G NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL E NL NL G E F G NL G NL NL G G NL NL F/G G F/G G/E NL G/E G NL G G NL P/F NL NL F G NL G NL NL E/G E NL NL G/E NL G/E NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL F NL NL NL NL NL NL P NL F/G P/F NL NL P/F G NL NL NL G F/G E E/G NL NL NL NL G F/G NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL G/E NL G NL NL NL NL F NL NL G/E NL P NL G/E NL NL NL NL E NL NL E G G NL NL E G/E E E/G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL F/G F/G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL E/G Edited by Dr. Mark Abney, University of Georgia Extension Entomologist E = Excellent Control; G = Good Control; F = Fair Control; P = Poor Control; NL = Not Labeled; LS = Labeled for suppression only 1 Dipel and others; * Insufficient data Burrower Bug Burrower bugs can be hard to identify in the field and an infestation is often not detected until harvest. Burrower bugs have a black-tobrown body, small red eyes on a small-sized head. The upper wings of burrower bugs are shiny and semi-hardened with the membranous tip overlapping. Its legs are spiny, and needle-like, piercing, sucking mouth parts are visible with a hand lens. Burrower bug is closely related to stink bugs. Threecornered Alfalfa Hopper Threecornered alfalfa hoppers are light green and wedge shaped. They stand about ¼ inch high and are about ¼ inch long. Both adults and nymphs have piercing mouth parts and feed by penetrating the stem and sucking plant juices. They tend to feed in a circular fashion around a stem, making feeding punctures as they go. The damaged area typically swells, and above-ground root growth may occur. On peanuts, feeding may occur on limbs, leaf petioles or pegs. Danitol Diamond EC Comite/Omite Warrior II Lannate Lorsban 4E Chlorpyrifos 15G Orthene Radiant SC Sevin Steward Thimet 20G Blackhawk Dimilin Intrepid Prevathon P/F NL NL NL G NL G/E NL G G E G NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL E NL NL G E F G NL G NL NL G G NL NL F/G G F/G G/E NL G/E G NL G G NL P/F NL NL F G NL G NL NL E/G E NL NL G/E NL G/E NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL F NL NL NL NL NL NL P NL F/G P/F NL NL P/F G NL NL NL G F/G E E/G NL NL NL NL G F/G NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL G/E NL G NL NL NL NL F NL NL G/E NL P NL G/E NL NL NL NL E NL NL E G G NL NL E G/E E E/G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL F/G F/G NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL NL E/G Edited by Dr. Mark Abney, University of Georgia Extension Entomologist E = Excellent Control; G = Good Control; F = Fair Control; P = Poor Control; NL = Not Labeled; LS = Labeled for suppression only 1 Dipel and others; * Insufficient data Burrower Bug Burrower bugs can be hard to identify in the field, and an infestation is often not detected until harvest. Burrower bugs have a black or brown body and small, red eyes on a small-sized head. The upper wings of burrower bugs are shiny and semi-hardened with the membranous tip overlapping. Its legs are spiny and needle-like. Piercing, sucking mouth parts are visible with a hand lens. Burrower bug is closely related to stink bugs. and feed directly on pegs and pods. Eggs and small rootworms cannot survive in dry soil conditions. Therefore, irrigation or a wet weather pattern will favor development of the pest. Adult beetles can be readily detected in peanut fields. Their presence in moderate to high numbers is a warning that a problem could develop. SCOUTING Finding rootworms in the soil is difficult, and injury is often not detected until after peanuts are dug when it is too late for control measures. Scout for SCR by pulling up plants and examining the roots and pods for feeding injury and sifting through the loose soil to find the larvae. It may be necessary to wash off wet or clay soils to clearly see damaged pods. Rapid growth after rain can cause short splits or creases to occur in the outer pod wall that can be confused with SCR damage. This pest is more likely to be found in low spots and heavier-textured soils under moist conditions or with center-pivot irrigation. Areas with increased loam content in the soil and poor drainage are also at risk of increased pod damage. MANAGEMENT Rootworm management options are limited. Granular chlorpyrifos banded over the row is the only treatment proven to be effective against this pest in peanut. According to research conducted in Virginia and North Carolina, preventative insecticide applications made before infestations are established provide good control. There are no foliar insecticide treatments available, and targeting the adult beetle has not been shown to reduce injury or improve yields. Determine the need to treat on a field-by-field basis. Decisions can be based on both adult populations and past history in peanut fields. Treatment late in the season following significant rainfall may be too late to effectively prevent rootworm injury. Late-season treatments may also encourage spider mite outbreaks. PG SCR Advisory For V-C Producers The southern corn rootworm is considered a major pest in North Carolina and Virginia peanuts. However, not all fields need to be treated for SCR. Virginia Tech's Tidewater Agricultural Research and Extension Center entomologist Sally Taylor says, “Knowledge of the past history of rootworm injury is useful in determining the need for treatment. If injury has occurred in a field, it will again. "Keep field records on the extent of pod and peg injury noticed at harvest time. Pay particular attention to fields with higher levels of organic matter and clay. Rootworms have a higher survival rate in those soils due to higher moisture-holding capacity, and injury will typically be more severe than in light soils." In the V-C, the Peanut Southern Corn Rootworm Advisory is available to aid producers to determine when fields need treatment. A digital version of the advisory can be found on the Virginia Cooperative Extension’s Publications and Educational Resources website at https:// www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/. Click on “Crops” to search the list, or search by publication identification for VCE Publication 444-351. It is also available for download as a PDF. The advisory is designed to help determine in a few minutes whether fields need an insecticide treatment. PG SCR larvae feed on pods, causing damage shown here. The discoloration is from storage. 10 Key Impacts Of Cover Crops On Soil Health C over crops protect and improve the soil when a cash crop is not growing. Ways that cover crops lead to better soil health and potentially better farm profits are outlined in the following 10 key impacts. 1 Cover crops feed many types of soil organisms. Most soil fungi and bacteria are beneficial to crops. They feed on carbohydrates from plant roots and release nutrients, such as nitrogen or phosphorus, to the crop. Earthworms and arthropods eat fungi and bacteria. Cover crops support the entire soil food web. 2 Cover crops increase the number of earthworms. Cover crops typically lead to greater earthworm numbers and diversity. Earthworms like nightcrawlers tunnel vertically, while others, like redworms, tunnel horizontally. Both create channels for crop roots and for water and air to move into the soil. 3 Cover crops build soil carbon and soil organic matter. Cover crops use sunlight and carbon dioxide to make carbon-based molecules. Some of the carbon is recycled through soil organisms, but some becomes humic substances that build soil organic matter, improving nutrient and moisture availability. 4 Cover crops contribute to better management of soil nutrients. By building soil organic matter, cover crops may impact the need for fertilizer. Cover crops scavenge for nutrients and hold nitrogen rather than letting it escape into rivers or groundwater. The nitrogen is released to the next year’s crop. 5 Cover crops help keep the soil covered. Rain is likely to cause bare soil to erode, form a crust or overheat in direct sun. Some bare soils can reach 140 degrees, killing soil organisms and stressing the crop. Cover crop residue protects the soil. 6 Cover crops improve the biodiversity in farm fields. Generally, the more plant diversity in a field and the longer that living roots are growing, the more biodiversity there will be in soil organisms, leading to healthier soil. Growing mixes of cover crops improves diversity. 7 Cover crops aerate the soil and help rain go into the soil. Cover crops open up soil channels for rain. This is particularly the case under minimum tillage. The rain that soaks into the soil instead of running off makes a big difference for crop yields. The extra aeration created by roots and earthworms benefits crop roots and other soil organisms. 8 Cover crops reduce soil compaction and improve the structure and strength. Excess tillage destroys soil structure, while cover crops and the soil organisms create the glomalin or the glue that binds soil particles together, leading to better soil aggregation and strong soil structure. Cover crops and earthworms help loosen compacted soil more effectively than subsoiling equipment. 9 Cover crops make it easier to integrate livestock with field crops. Think of buffalo herds foraging on prairies, and you can see how natural systems evolved to have an integration of plants and grazing animals. The manure from livestock grazing can be beneficial for building organic matter and soil health. It is also a way to profit from cover crops. 10 Cover crops greatly reduce soil erosion and loss. The future of our food supply depends on topsoil, and cover crops are exceptional at helping stop erosion. No-till with cover crops reduces erosion to a fraction of what it would be. Even with light tillage, a field with cover crops is still better protected. PG Article from the Southern Agriculture Research and Education program. For information, visit www.sare.org/covercrops. Four principles for improving and maintaining soil health: • Keep the soil covered as much as possible. • Disturb the soil as little as possible. • Keep plants growing throughout the year to feed the soil. • Diversify crop rotations as much as possible, including cover crops.

Pearman Peanut Digger-Shaker-Inverter Choose Pearman when every peanut counts!

• • 1,2,3,4,5,6 and 8 Row Models – 26 to 40 inches, single or twin rows Gently harvest ALL Varieties: Runners, Spanish, Virginia and Valencia • • Parallel Digging Chains and Three Simple Inverting Rods help save Peanuts Ask about our PENCO Single Disc Liquid Fertilizer row units and Peanut

Moisture Sample Shellers

PEARMAN CORPORATION 351 SHAKY BAY ROAD CHULA GA 31733 USA Phone: 229-382-9947 Fax: 229-382-1362 www.pearmancorp.com bpearman@pearmancorp.com