e v i e w 44: 2024

architecture and play ON SITE r

On Site review is published by Field Notes Press, which promotes field work in matters architectural, cultural and spatial.

For any and all inquiries, please use the contact form at https://onsitereview.ca/contact-us

ISSN 1481-8280

copyright: On Site review. All rights reserved.

The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of Copyright Law Chapter C-30, RSC1988.

Each individual essay and all the images therein are also the copyright of each author.

back issues: www.onsitereview.ca

these are listed in the website menu in three groupings: issues 5-16, 17-34 and 35-43

editor:

Stephanie White

design:

Black Dog Running

printer: Kallen Printing, Calgary Alberta https://kallenprint.com

subscriptions:

libraries: EBSCO On-Site review #3371594 at www.ebsco.com

individual: www.onsitereview.ca/subscribe

This issue of On Site review was put together in Calgary on the Treaty 7 territory of the Kainai, Siksika, Piikani, Tsuut’ina and Stoney Nakoda First Nations; a territory which covers southern Alberta: 130,000km2, roughly the size of Greece. Mistranslated and unexplained, Treaty 7 was signed in 1877, effectively seizing all land other than limited reserves. This is considered today to be contested and unceded land.

F I E L D ON SITE r e v i e w 44: 2024 play

66 x 13 x 13”

N O T E S

Alexa McCrady, Antennae. wood, vermiculite, flashe.

www.alexamaccrady.com

contents

Ruth Oldham and Emelie Queney

Stephanie White

Darine Choueiri

Samer Wanan

Yvonne Singer

Yiou Wang

Ivan Hernandez Quintela

Amra Alagic, Lara Kurosky and Lea Dykstra

Aurore Maren

Carol Kleinfeldt

Tim Ingleby

Harrison Lane

Metis: Adrian Hawker and Mark Dorrian

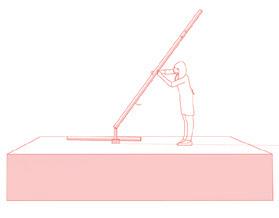

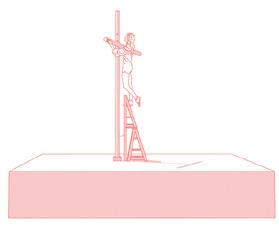

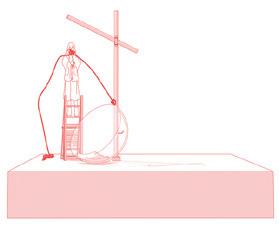

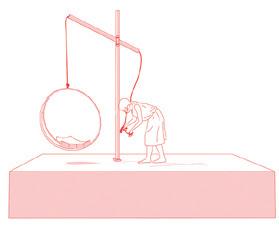

it started with a bolobat, became a building site. 1989

architecture and play

There are several ways to think about play, the most obvious one being the one which children, with great imagination and entertainment, do, learning as they go. Then there is organised play, sports and such, games involving opposing players of great prowess, skill and combativeness. And somewhere inbetween is the play that involves messing around for the sake of meaningless joy: play for the sake of play.

There is another use of the word play, which is the looseness in a system. Mechanical parts that have some play are not highly machined, or if they once were are now worn, introducing a play between parts. This is very interesting, that the word play describes this sloppiness, where exactitude is not a factor.

en jeu air mindedness play in wartime schoolscapes

child’s play in the Palestinian landscape (for)play and wordplay minotaur plays Ludius Loci play ground

nest and branch play in three acts

BMX Supercross Legacy Track game changers joy as an act of resistance front and back covers calls for arrticles

The architecture of play is linked indubitably to Aldo van Eyck’s schools and playgrounds, and from there all the theories of education, learning and play that so dominated the twentieth century. Increasingly, either through psychology, ideology or health and safety regulations, play has become channelled, scheduled – something closer to a machined part in a busy life than poking about a ditch with a stick. for hours. till dinner time.

Somewhere in all of this is the sense that joy is for children, that eventually one puts aside childish things and gets on with some other form of life, usually something more grim, less joyous. Something we see in the tragic children of war who have been forced to put aside childish things almost from birth.

In the practice of architecture do we have works conceived, designed and built with joy throughout the whole process? Where the sense of play is there from the start, an architecture of simple pleasures, of ridiculous time-wasting that is vastly pleasurable? This transcends program and looks squarely at the process of making architecture.

What is the relationship between architecture and play?

on site review 44 : play 1

2 6 10 17 2 2 24 30 42 4 6 4 8 52 56 64

en jeu

RUTH OLDHAM and EMILIE QUENEY

We are Emilie and Ruth. Emilie is from France but lives in the UK . Ruth is from the UK but lives in France. Language-location mirror (and we tend to speak in French and write in English) We are both qualified architects though neither of us practices, in the traditional sense, anymore. However, we do continue to work very closely around architecture, probably in search of some, or more, playfulness.

We have started a conversation in response to the call for articles for issue 44, ‘architecture and play’. Ruth told Emilie about the call, as it was so closely connected to her work. Emilie suggested they respond together. Ruth had just returned from a conference workshop about collective collaborative writing so this seemed like a fun idea.

How might the ping-pong of ideas make new thoughts emerge, enable more creativity and elasticity in the thinking, more nourishment of ideas and more discussion? I find exciting the fact of creating a situation of play in the act of writing itself, by giving that game rules, time and free thinking.

We began by asking ourselves some questions:

What do we want to say about architecture and play?

How can we think and write together?

Can we write a text as a dialogue? As a cadavre exquis?

Can I give you a word and you respond, and vice-versa?

What if we take some words from the call, and respond to them?

If the rules/limits/framework of this game are that it is a dialogue, taking place on the page, what might we manage to say?

for the sake of play

I feel we should start with this. ‘ Sake’ is such an amazing English word, so appropriate in this case, and not easy to translate into French. Looking at the etymology, I can see there is no common root, so it might just be a fantasy, but for me, it has a sense of sacredness.

Ha! This is great, I had never really thought about how hard it is to translate ‘sake’ but it is a curious word, and I kind of understand why you link it to sacredness... There is a sort of linguistic playfulness... the two words have a phonetic similarity, and a connection in terms of meaning...; for the sake of something, means that something is special, sacred, an effort must be made to preserve it.

And indeed, even if we are in a world where playfulness is everywhere, as a gamification in service of making capitalism as enjoyable as possible, we can’t reduce play to a pleasurable addition to our daily lives. Play has no use, or at least can’t be reduced to definite functions or categories such as pleasure, education, physical exploration, expending excess energy, expression of competitiveness, enacting fantasies, sport, gambling, role play, etc...

Play is linked to our human condition, beyond anything reasonable and pragmatic, it expresses our intrinsic thirsts and needs. Friedrich Schiller wrote, ‘Man only plays when he is in the fullest sense of the word a human being, and he is only fully a human being when he plays’.

This is where considering architecture regarding play touches my soul because architecture is also an expression of higher human aspirations, beyond any practicalities, something no one needs and everyone needs simultaneously. Looking at this necessity requires stepping back and taking a holistic view.

Thinking about the meaning of ‘sake’ led me to the word ‘stake’. Perhaps simply because it rhymes. What is at stake if we do not play? Our humanity!

For the sake of meaningless joy, we must play! For the sake of humanity, we must play!

And then the realisation that ‘at stake’ translates into ‘en jeu’ in French.

Ce qui rentre en jeu par le jeu (what is at stake through play), or even, ce que met en jeu l’absence du jeu (what is at stake when there is no play).

In Homo Ludens, Johann Huizinga studied play and place in this holistic, sacred and humanist context: free (in all senses), having its own place, rules, order and time. Through play, one spontaneously experiments and lives something not yet known and therefore grows from that experience.

on site review 44 : play © 2

Oldham+Queney

sloppiness

This process starts out feeling rather sloppy. While I am enjoying these pages of thoughts, notes, references, connections, and the sort of curious complicity in knowing that you have this document open on your computer as I write, even though I can’t quite be sure if you are reading the same part as me, I keep getting quick anxious thoughts about how difficult it is to make sense of the different ideas. How to write together, how to write when you don’t really know where it might go? Maybe this is: messing around for the sake of meaningless joy – turn off the anxious voice that requires a ‘plan’ and see where things go… part of me wants to start a new document, to follow the rules of a cadavre exquis, to take it in turns, to progress in a linear manner… then this other voice is saying no, just stick with this… but how can this become publishable article?

Yes, I agree: spending time to think with you about how play is or can be part of architecture is definitively bringing meaningless joy. It will not add anything to the world but this present shared bubble of thinking, discussing, imagining, letting our minds wander, and reflecting, which is pure play. I love as well how we can build this text from different places, and simultaneously, embrace this way of co-constructing thoughts, as opposed to pretending to start with the beginning and finish with the end.

Related to architecture, this makes me think of architects whose creative process generously makes room for moments of collective sharing and provides a space of ‘ridiculous timewasting that is vastly pleasurable’.

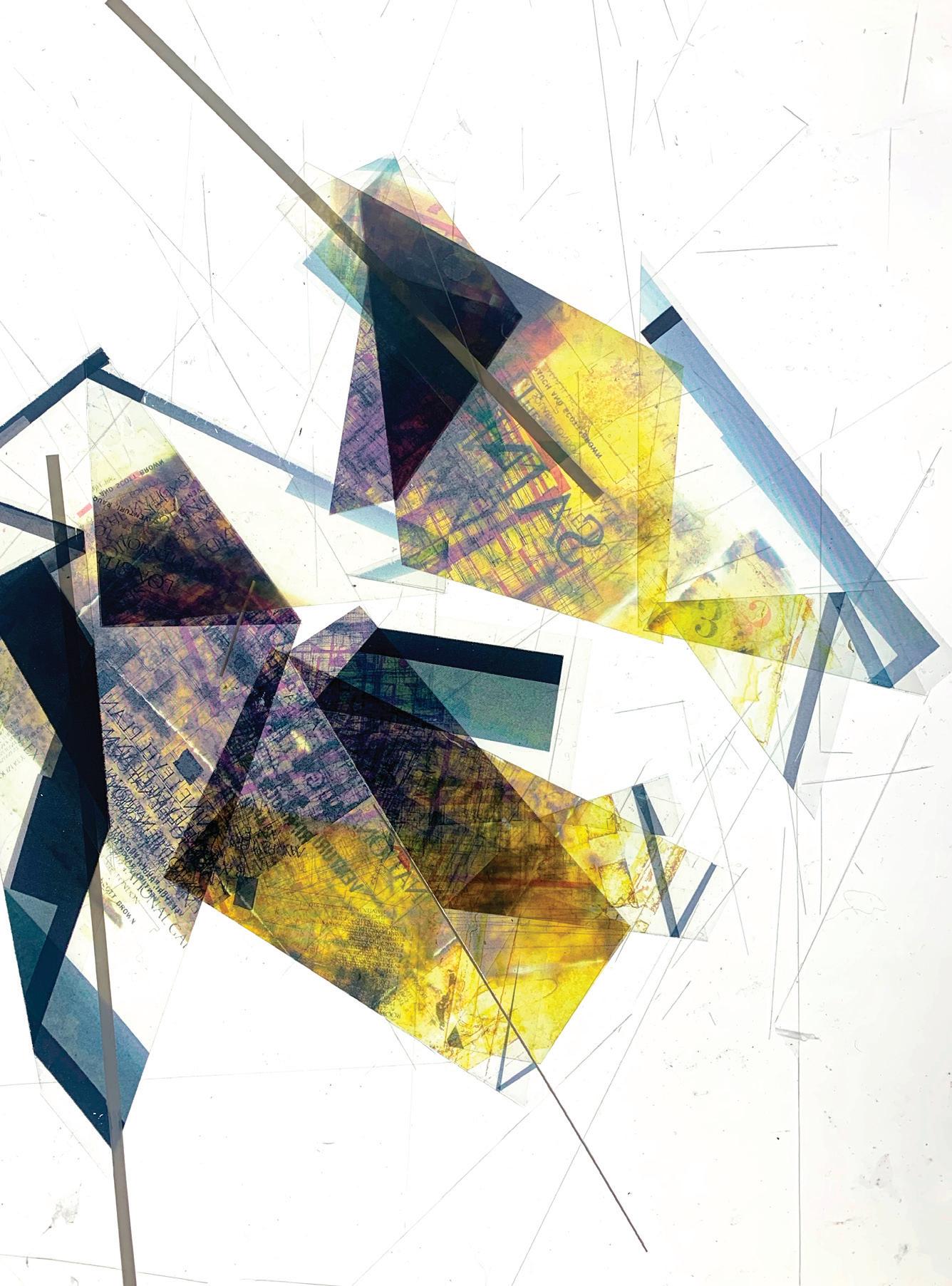

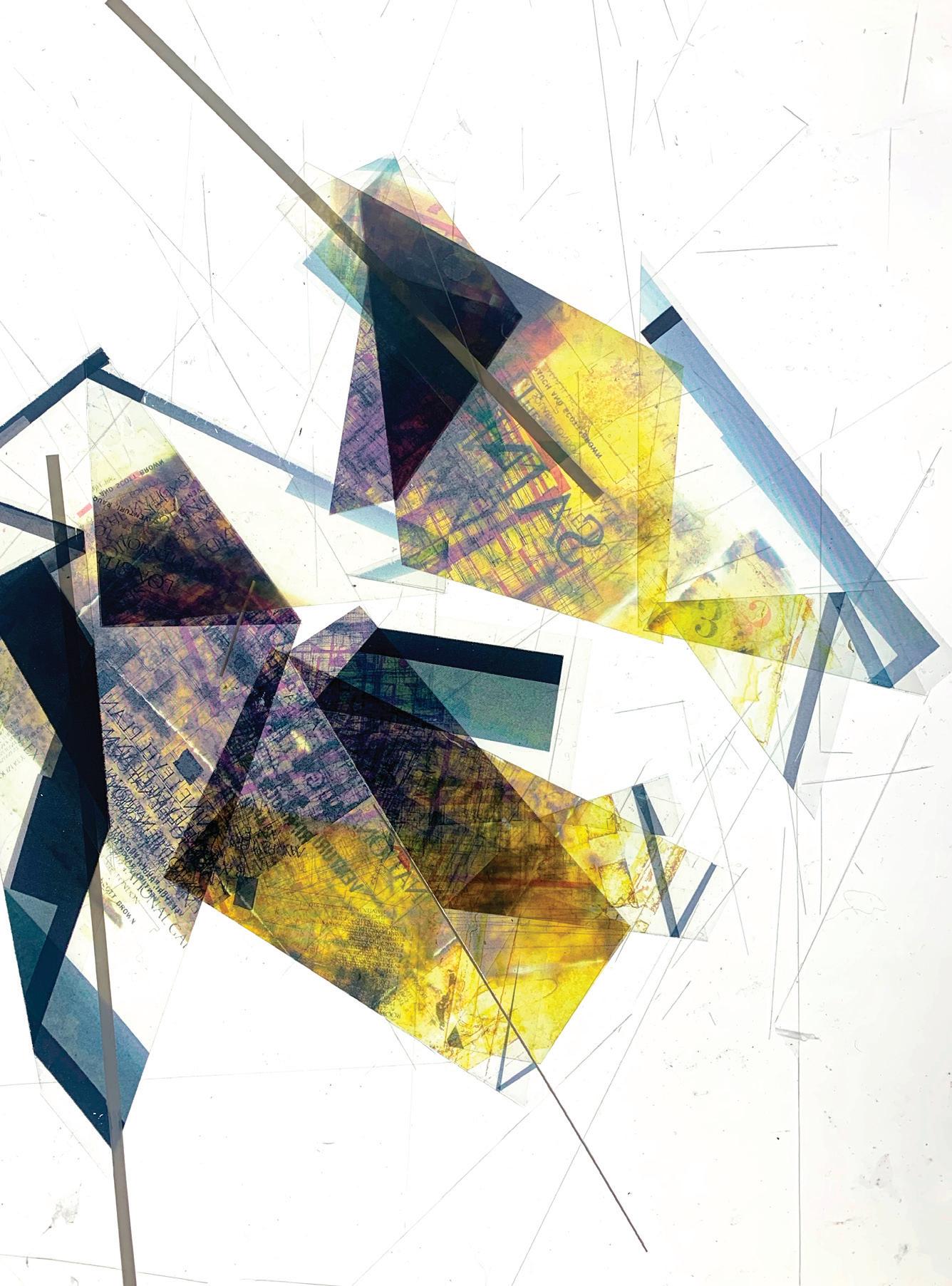

This section begins with the word ‘sloppiness’, which almost feels like a rude word, a bit shocking. But it is a starting point, a way into a thinking space, a space in which to explore the relationship between that which might appear superfluous, minor, irrelevant, frivolous, pointless (messing around, time wasting) and the realm of the serious, important, worthwhile, necessary (making real and useful buildings?). I am thinking about drawing. Architects make drawings in order to ultimately make buildings. They make many more drawings than they make buildings. In the wake of each completed building will be innumerable drawings, from early sketches, to process sketches, plans, sections, façades, axonometrics, perspectives. Exploratory versions and finished versions. Then details, construction drawings. Not to mention diagrams, schemas… Even unbuilt projects generate dozens, often hundreds of drawings. But before drawings that are related to specific projects, built or unbuilt, come a multitude of other drawings. Doodles, sketches, patterns, portraits, still lifes, landscapes, cityscapes, survey drawings. Made with pencils, crayons, pens, biros, watercolours, charcoal… on ipads, on paper, in notebooks, on tablecloths... Architects’ language is drawing. The other day I leafed through a beautiful book of 700 of Peter Markli’s drawings. Consisting generally of just a

few lines and /or blocks of colour, they might appear closer to the realm of doodles or jottings, barely even sketches let alone technical drawing, yet they express hundreds of spatial and architectural ideas, suggesting plans, façades, spaces, rooms, buildings, houses, landscapes, places, structures, systems, atmospheres. Here is Markli talking about these drawings: ‘There was no client, no direct commission, for any of these drawings. Instead, they were ways of exploring the form and the expression of a house – things I was still looking for in the 1970s, and these drawings helped me find them. When I had the good luck to get a commission I was able to refer back to some of these things. Without this work, I would not have been able to build – to realise –the buildings.’ 1

And,

‘These are hardly what I’d call virtuoso drawings. They’re drawings that I’ve had to work at, correct. That is why there are so many of them. The work is not a virtuoso exercise. It’s about thinking things through, looking for something that doesn’t yet exist in this form.”

This makes me think of the use of hands in the process of drawing, and the sloppiness of first drawings and sketches. The hands, using drawings or models search, explore, reveal and find, independently of the head. For this to happen, sloppiness must be allowed. The hand does not necessarily depend on the head and vice versa. The exploration, reflection and testing process of architectural ideas goes through the hand and the drawings, pictures or models. There is some playing space between head and hands. Ideas and concepts emerge in the space created between both. All that is left from that play margin is the physical mass of graphic documentation.

Going back to the creative processes thread, I am thinking of participative projects, where time is made for ideas and feelings to flourish, be expressed and react to each other. The German practice Raumlabor and the Rome-based Stalker incorporate times of exchange, conviviality, and collective exploration in their projects. Spaces are established during those processes. But these spaces are not created via a regular design process (brief - conception - construction), they arise from this floppiness: times of conviviality, exchange, imagination or even protest. The way these spaces take form confers upon them more than just a spatial quality: but also an emotional, social and political dimension. This involves losing the aim of conceiving a finished space in aid of moments, periods of time, situations (as the Situationists intended), and exchanges.

1 https://drawingmatter.org/peter-markli-my-facadematerial/ accessed 12.01.2024

on site review 44 : play 3

imagination

Architecture can sometimes support the imagination, through materials or shapes inviting dreams to be more real and giving physicality to poetry. It plays with our senses, and our ideas about what buildings should be.

I think that the idea of ‘materials and shapes inviting dreams to be more real’ is wonderful. It makes me think of a collage by Jacques Simon (French landscape architect) showing a photo of a kid balancing on some bollards with a thought bubble of mountain peaks sketched and pasted onto it.

Yes! Materials and shapes can summon sensations or memories. In opening this door, they enable architecture to be experienced in ways unique for each person, who will create their own creative and sensory links. Thinking of my own experiences, I can consciously see that I love the Barbican interior spaces and Zumthor’s thermal baths for their womb/ grotto-like character. Or that wooden buildings make me go back inside my grandfather’s carpentry workshop. Or that sitting in a high-up window is like disappearing in a den.

A window seat with a view is one of my favourite types of places and I spent a lot of my childhood sitting on my bedroom windowsill watching the world (mostly birds and the odd car) go by.

combativeness

Nowadays, architectural practice is sometimes reduced to the point of absurdity, to the management of a juxtaposition of different areas of expertise framed by technical and legislative issues. On the fringes of the conventional mode of exercise, however, emerges a multitude of relentlessly creative, inventive, and original practices, as if the force of human invention, so constrained on one side, inevitably resurges on the other. A powerful illustration of this position can be seen in architectural activism which defies authority by diverting or hijacking official rules.

Combativeness also refers to the idea of sparring, of exchanging, of having good-natured arguments. While I’m not sure we will start arguing in these pages, I like the idea of bouncing off one another. And is this not at the heart of many people’s creative processes? So many architectural practices are led by a pair. Often with quite different identities and approaches.

Coming up with ideas, developing them, communicating them… these processes can operate via visual media - drawing, image making, model making… but also via language, spoken or written. Different individuals have different aptitudes and inclinations. Is establishing some kind of method the first creative act? Imagining the rules and boundaries of a game that allows for creativity and invention? One of my old tutors in architecture school, who ran a practice with his wife, said that they would make a series of quick models and drawings independently of each other, to a given deadline, before

showing each other their ideas and attempting to combine them or choose between them. They would then repeat this process several times as the project developed: makingtalking - making - talking. In an interview, 2 Sarah Wigglesworth described how she and Jeremy Till worked on the early stages of designing Stock Orchard Street (their home and workspace, completed in 2001)

‘... we’re two architects… and as you know, there’s kind of, a bit of competition between architects about how you work together (...) who puts marks on the page and stuff like that, so we made a rule that we would only talk about it, we wouldn’t draw anything at all...”

In another interview, 3 she explains the process further.

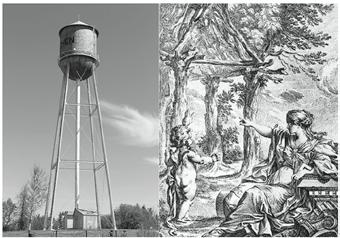

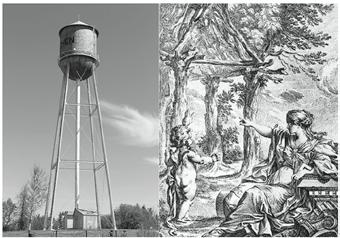

“I think one of the things we were trying to explore there was the idea of authorship, and we wanted to both claim authorship… and the problem is, when one of puts something down on paper, they tend to start claiming it, and if we were going to have a kind of equal relationship in what we did there, then that’s a bad idea, so we’re just going to fantasise about it. So we actually spent about four years just talking about it! And dreaming about what it could be like… you know, silly ideas like ‘oh it’s going to be up on stilts, or oh I really like this building by x or y, or, I want a tower because I want a place of dreams… (...) and eventually, I think the agenda about living and working, about these two separate buildings which were joined but separate… it all just began to fall into place… (...) I think it was very fully formed as a set of ideas before it got put on paper, and I think that’s very important if you want to both have a say in it.’

This idea of dialogue and combativeness makes me think of the Antepavillion project conducted in London-Hackney, which aims to fight gentrification in favour of affordable artists and community spaces.4 Since 2017, through yearly architecture projects, the traditional way of producing architecture has been challenged, in terms of functions, shapes, material sourcing and building standards. There is a dimension of fun, creativity and playfulness in each single pavilion. As it happened, the borough authority itself felt challenged, and each pavilion is now the very tool of a creative and inventive fight between the rigidity of this institution and what a playful architecture practice could be.

Play can be seen as an inherent act of rebellion. When the freedom conveyed by play is so close to anarchism, combativeness puts into question the position of architecture in relation to authority and institutions. I believe it is there, in that very context, that architecture can be questioned and reinvented in a meaningful way.

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-3Vx9KrfTQ accessed 12.01.2024

3 https://materialmatters.design/Sarah-Wigglesworth accessed 12.01.2024

4 https://www.antepavilion.org/ accessed 12.01.2024

on site review 44 : play © 4

Oldham+Queney

looseness

There are architects who find a way to respond to the multiple regulatory constraints that nearly every contemporary project is subjected to, in a playful way.

Found in mechanics or joinery, play is the essential room for tight parts to work together just right. In the call for submissions, it is suggested that this looseness means that ‘exactitude is not a factor’. But, if we look closely, the space for this lack of exactitude is very precisely established - not too tight, and not too loose. In French, this room has the same name as play itself: jeu

In architecture projects, this looseness exists between the rules (standards, norms, finances, politics): this is where creativity and invention can take place, where the project can be more than a logical and exact answer to a series of constraints, or when art adds to technique.

Thinking about this idea made me think of Koolhaas. I have lodged in my mind this idea that his approach is to almost relish, devour even, the multitude of crisscrossing, complex, often contradictory webs of legal, programmatic, financial, and other constraints that condition every contemporary project. Along with glass and corrugated plastic and plywood and concrete and perforated metal and extruded aluminium and gold paint, these rules and norms and standards and constraints are part of OMA’s material palette/resource box/tool kit. As if they are understood as physical tangible ‘stuff’ that shapes and forms space and atmosphere. Making architecture an elusive art of applying the rules but not letting them rule.

Children would be the best teachers about this: whatever rules and planned uses are made, the only certainty is their ability to find the tiniest possibility of creating something which has not been thought of. This is the spirit which is cultivated here: how to agree and comply, and at the same time find the little interval allowing for creativity and invention. What a great source of joy this can provide!

And as well as rules, regulations, norms, standards, and budget restrictions there are other less precise constraints that can exert a subtle pressure on the design process. To do with the current accepted paradigm, what is considered ‘good’ or ‘bad’ practice, how to position oneself in relation to fashions, to the zeitgeist...how to navigate between finding one’s own voice and being influenced by others, being original but not necessarily being original for the sake of being original. I will return to Sarah Wigglesworth: Stock Orchard Street was criticised by some for containing too many ideas, and she has noted that at the time (late 90s and early 2000s) minimalism was the dominant aesthetic. She was using words like hairy, messy, baggy, rough, to talk about the building and its materiality.

‘It’s not about minimising it to a kind of core… to me it’s more about a kind of layering, or a sort of palimpsest of a

5 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-3Vx9KrfTQ accessed 12.01.2024

series of ideas… which you know, to a lot of people might be a very baggy, and quite incoherent and the rest of it, but actually, the flipside of the coin is, it could be regarded as richness, or embracing a range of different things simultaneously… and I think I’m much more interested in that, I mean, I don’t really care if it’s incoherent! What does it mean to be incoherent? Whose incoherence is it?’ 5

This makes me think of New Babylon, a Situationist urban and architectural project, a revolutionary and subversive way of conceiving life. This nomadic city was designed for constant play. Its design would allow everyone to drift, and live indefinitely and spontaneously create new situations and new experiences. This was a rethinking of society itself as well as its urban form, where values such as ‘coherence’ don’t mean much in comparison to permanent freedom of experimentation.

Arriving at the end of this writing experiment, I can see that not only have we touched upon all my thoughts about the initial theme, but that the dialogue form has enabled the pulling together of new threads, in the space between our two heads, touching a range of new ideas, making new connections, experiencing something light and new and embracing the unknown, which is exactly the aim of play. The result has no structure, as the raw start of something more ordered. Hopefully, it can allow readers’ thoughts to emerge and wander.

When we set out, we wondered if the process of writing and thinking together, sitting somewhere between ‘organised play’ and ‘messing around’, could be a way of playing together and creating together. It has certainly been a way of playing together. Writing is usually quite a solitary affair, but developing this text together, in equal parts, brought about a feeling of complicity. Adding some text and wondering how the other would react, sometimes working on the document simultaneously but on different parts. Sometimes talking on the phone (in French) as we edited parts together, sentences contracting and expanding in surprising ways as we both cut and added parts. The resulting text wanders and meanders, sometimes stops and starts, but it has definitely also been a way of creating together. It feels like a beginning.

It ’s a bit messy but that’s ok. £

RUTH OLDHAM teaches, writes, designs and translates, within and around the field of architecture. Originally from Kent in the UK, she now lives in Montreuil in the eastern suburbs of Paris. @_rutholdham_

EMILIE QUENEY is passionate about creating installations, workshops, objects and videos around the subjects of play, craft and architecture. Born in France, she has been based in London since 2014. www.emiliequeney.com

on site review 44 : play 5

air mindedness

drawings of a very young architect

STEPHANIE WHITE; proposed by David Murray, and help from a host of Hemingways: Mistaya Hemingway, Enid Palmer and Guy Palmer

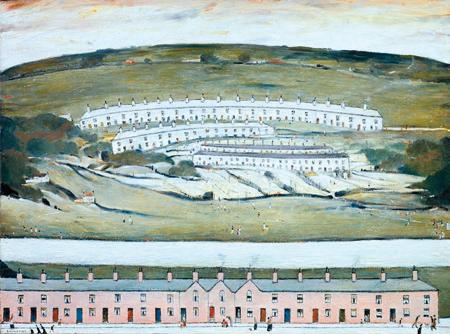

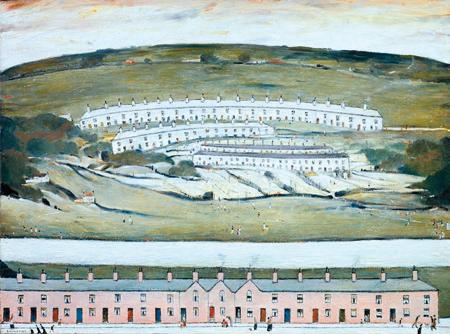

Peter Hemingway was an architect in Edmonton, Alberta, well-known, well-awarded, a personality about town, political, outspoken, a fine architect.

Born in 1929, he grew up in Minster-on-Sea on the Isle of Sheppey where the Thames meets the English Channel: for centuries the front line against invasion. The Second World War was no exception, Sheppey’s north and east coastline bristled with fortified beaches and anti-aircraft installations, with a second line set back from the coast. As it flanked the route for aircraft flying up the Thames to bomb London, it was so strategically important that the island’s children were evacuated in 1940. Peter and his sister Enid were sent to Yorkshire, where he was so unhappy that he was sent back to Minster.

Was he homesick? Something tells me no. Missing the war, the excitement, the urgency of being part of something so huge – it must have rankled.

This file of drawings done by Peter Hemingway when he was 11 or 12 is from Hemingway’s archives, held by his daughter Mistaya. Are drawings play? They are undoubtedly something children do from a very early age. Is drawing different from playing with toys? Hand to eye coordination is being learned, refined, imagined. But that is neither interesting nor informative for this little book of drawings of WWII aircraft, carefully drafted, coloured and labelled in irreverent verse.

History is written magisterially, in text, by historians who paint enormous histories that document events, dates, places, protagonists, victims, economies and aftermaths. The study of material culture finds smaller stories in smaller objects; it fills in the human daily lived life on the ground which often goes unnoticed by events, politics and ideology, yet contributes to them. As On Site review is interested in architecture as material culture, it is a simple thing for research purposes to flip this to material culture as architecture, and then one must ask, what kind of architecture are we looking at?

on site review 44 : play © 6

all images courtesy of Mistaya Hemingway

Mistaya Hemingway

For these drawings it is the architecture of childhood during war, specifically how a boy might fill a notebook with the fierce components of an air war.

Gabriel Moshenska writes in Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain about the ways that children directly engaged in wartime activities, from collecting and trading shrapnel, playing in bomb sites, using their cardboard gas mask cases as satchels for findings, to aircraft spotting.1 Specifically there was an air-mindedness in Britain promoted in the press, in aviation magazines, children’s books and air pageants: waves of bomber aircraft were necessary components of modern warfare. 2 The avant garde nature of such warfare was kept at the forefront of the public mind as battles were fought noisily and visibly in immediate British airspace, not somewhere else as on the high seas with the Navy, or in Europe, Africa or the Far East with the Army. Plane spotting for children was competitive and obsessive.

Identifying aircraft by the particular sound of their engines or their silhouettes in the night sky, writing down registration numbers, all was useful war effort – either information to be telegraphed to RAF bases or ARP wardens, or simply just to know. There were clubs, there were magazines, there were the Biggles stories, RAF men were heroes; Peter’s older brother was in the RAF. Children, Moshenska writes, saw themselves as active participants in wartime society:

“If we want to understand childhood and its material worlds in Second World War Britain, or indeed anywhere, we need to start from this understanding of children as people, keenly observant and aware of their environments even as they are shaped by them, and reshape them for their own purposes.”

1 Moshenska, Gabriel, Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain. London: Routledge, 2019

2 B uitenhuis, Peter. The Great War of Words. British, American and Canadian Propaganda and Fiction, 1914-1933. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1987

on site review 44 : play 7

An anti-aircraft gun on the Isle of Sheppey, probably seen on the walk home from school.

all images courtesy of Mistaya Hemingway

One aspect of play is the miniaturisation of the world: everything becomes small: the ditch is a river, lead soldiers are an army, the rock in the woods is a mountain. Bits of shrapnel (a bomb), medals and buttons (a soldier), model aircraft (planes exploding overhead and destroying your house) become synecdoches of the disturbance of war at the scale of a child’s hand — controllable, collectible, evidence that one is alive. So too the drawings here, amplified or diminished by the verses and commentary. That which is traumatic is neutralised by being made small while at the same time being part of something as enormous as a war. The Right to Play movement which is about child labour, might in what appears so far to be a war-torn twenty-first century, go hand in hand with being allowed to play, allowed to process what is happening by translating it into artefacts, collections, games with arcane rules, drawings and stories: a kind of material resistance. A survivalist response. £

on site review 44 : play © 8

all images courtesy of Mistaya Hemingway

Mistaya Hemingway

Enid writes to Mistaya:

‘It was a popular thing in teenage years to collect autographs of family and friends but Peter preferred to use the blank pages to draw aeroplanes and my father added the words to the drawings. These are pretty exact drawing of each plane as it was necessary to recognise English planes or German ones. On one occasion your Dad and Ralph cycling home across a grass track on the marsh were machine gunned by a German plane and Ralph threw them both in a ditch as the bullets hit the path. pps. Your Dad would have been almost 10 when the war started and possibly 12 or 13 when he did these drawings.’

and a later note:

‘We went by train to school each day and slept in our own beds unless there was an air raid siren. The raids generally stopped in mid ’41-ish and only really started again in ’44 with the V1s. Dad was out all the time in the evenings. Peter could have been drawing any time as the book was small and portable.’

MISTAYA HEMINGWAY is a freelance dancer, choreographer, filmmaker and urban thinker living in Montreal. A soloist for nine years with La La Human Steps, she holds a degree in urban planning: these are blended to focus on artistic projects that unite movement, music, film and the city. She is currently working on an immersive installation that explores the architecture of Peter Hemingway through dance, scenography and XR technologies, accompanied by original composition by Sarah Pagé. www.mistayahemingway.com

on site review 44 : play 9

all images courtesy of Mistaya Hemingway

play in wartime schoolscapes

DARINE CHOUEIRI

courtesy

courtesy

of Čedo Pavlović

In this photo taken around 1993 in the Hrasno neighbourhood, the boy with the blue tank shirt is holding the carcass of a mortar. He is carefree, posing in the midst of two other friends sitting next to him, each of whom have also one of their hands reaching to touch the loot of the day. The photographer must have said something funny because the boy in yellow sitting on the ground, sealing the composition of this happy group, burst into a genuine laugh while the others, blinded by direct sunlight are smiling while wrinkling their eyes. A bike wheel sticks out from the left side of the photo, probably belonging to one of the boys and taken out on this sunny day for a trip in the neighbourhood.

The boy in the middle is Čedo Pavlović, from the neighbourhood of Hrasno; writtten in half-erased white letters on the black billboard crowning the four boys’ heads. Čedo sent me this photo in April 2022, exactly 30 years after the beginning of the siege of Sarajevo in 1992. This photo could have been a trivial one, like many others taken to keep a memory of the giddy years of childhood. But the defused mortar, the blown up store front and the car riddled with bullets give this photo a sense of the uncanny.

A mortar becomes a toy and destruction echoes a laugh.

the new structure of school: play by default

April 1992 the city of Sarajevo is under siege and the schools are closed. For children, war is perceived as a restriction of their freedom, a halt in their physical activities. Adults, aware of the pressure war exercises on children, start scattered initiatives to give children a sense of normality and a basic need: schooling. A person, often a professor, gathers children hiding in the basement of a building and organises a class.

These initiatives first appeared in the neighbourhood of Dobrinja and were referred to as Haustorska škola (stairway schools) because they occured in the lower parts of staircases, considered the safest in the apartment blocks. This practice soonl quickly built up into a local school system in Sarajevo, put in place by the Pedagogical Institute of the city. Schooling continued during the war and siege that Sarajevo painfully underwent for four years.

Darine Choueiri

Schooling adapted to the compelling situation of war and siege. In this altered pattern, space and schooling are linked beyond, and often without, the architecture of a specific school building.

The war school is a temporary suspension of the rules and hierarchies of regular schooling. A rhizomatic system is implemented, where schooling activity occurs in makeshift classrooms located in rooms considered safe, called punkts This network spread through the city, clinging to a spatial logic – the urban divisions inherited from the Yugoslav period named Mjesna Zajednice (MZ), or local communities. The MZ is the smallest urban unit to constitute a neighbourhood, or a fragment of a neighbourhood, its perimeter delimitated by streets or natural elements.

on site review 44 : play © 10

Each of the four municipalities of Sarajevo are composed of a number of Mjesna Zajednice, an urban structure that was also social; during the Yugoslav period these MZ were self-managed entities where residents autonomously made decisions on local issues. This existing structure actually facilitated the development of a rhizomatic school structure: all the children living in a particular MZ attended the same punkt located in it, no matter which primary or secondary school they had attended before the siege. Before, primary schools, gymnasiums and vocational schools might have a number of MZ under their responsibility, which meant finding

Map showing the contour of the Mjesna Zajedniča in black, and the schools in Sarajevo in red( outline: non-operative, solid red: operative)

Map of the itinerary of teachers from the high school Treća Gimnazija. In red, the school, its two relocations, the houses of the professors and the punkts. In black, residential settlements from the Yugoslav Socialist period.

and organising teachers and professors to give classes, keep records and organise exams in each one. If these Matična škola (mother schools) were destroyed, professors relocated to schools that were still operative or in other kinds of spaces. Thus school came to the children; it was always in their close vicinity, within walking distance from their homes which avoided displacement and limited danger in getting to and from school. Instead it was the teachers who had to walk often long distances from their houses to the punkts, when it was not too dangerous, to meet their students.

on site review 44 : play 11

Darine Choueiri

This reversal of the trip to school is a first détournement of the schooling structure. As well, spatial and curricular organisations were de-hierarchised: the central school building no longer existed, instead it dispersed to different punkts; class levels were blurred with students of different ages cramped in often small rooms.

Urban elements on the way to school also experienced a détournement. Some buildings were considered as shields because of their length and height and were nicknamed Pancirka (bulletproof jackets). Garbage bins became hideouts if sniper bullets were heard; damaged cars were filled with rubble and turned on their side making a buffer; in some neighbourhoods a trench was dug to ensure a safe route for children at some critical crossing point.

Darine Choueiri

on site review 44 : play © 12

from top: Students carrying a desk and running protected by the trashbins disposed along the way, students running to reach the punkt, Little light, big smile.

Students in a basement room, students crouching in a trench, students gathering under the porch in Emile Zola street.

Screenshots from You Tube movies by Smajo Kapetanović in the neighborhood of Dobrinja.

In some of the videos shot during the war, kids on their way to class, with their backpacks on their bent backs, are hurtling through a devastated street. With the sound of sniper bullets in the background, children gather under an entrance porch in Emile Zola Street in Dobrinja, chatting while waiting to the enter the small basement room where school will take place. In single file, children hurry up the trench with big defiant smiles. The primary school of Hrasno, a neighbourhood on the direct line of siege, was protected by the UNPROFOR (United Nations Protection Forces) with concrete panels wrapped around the perimeter of the building. It was cold and dark in the classrooms on the first floor but children could study, and came to do it. In the makeshift classrooms, school desks are generally missing, sometimes a table is turned up to become a board, and often children have oil lamps for light.

The teacher’s route: a drawing by Amina Avdagi ć, the director of the Treca Gymnazija during the siege. It shows a zone in a quarter of Hrasno to which the Treca Gymnazija was relocated in July 1994. Loris is a shield building, very long (relatively high) on the frontline, the border with the belligerent army on the other side. People ‘integrated’ it spatially to their itineraries because it was good protection from snipers In their war jargon, it is a Pan č irka, a bulletproof jacket.

A fuller discussion of this specific school is found in Darine Chouieri, ‘Sarajevo Schooling Under Siege’, Mémoires en Jeu/ Memories at Stake, numèro 18, Printemps 2023. https://atablewithaview.com/mapping-schooling-undersiege-an-interview/

war, play and the architectural agenda

In besieged Sarajevo, schooling gave way to what I call play by default: common elements of daily life were played out to become extraordinary; even the path to school was an adventurous slalom where children had to thwart the snipers.

Schooling does occur in extremely dangerous conditions, but danger is an abstraction for children and that is why they can play out school. Risk is a fundamental aspect of play according to Lady Allen of Hurtwood, the designer of adventure playgrounds in postwar Britain; in Sarajevo children assumed risk and canalised it through their schooling activity. The war lasted four years; children died because they went outside to play. But how to keep a child in the basement that long?

This also changed their involvement in the socio-public sphere. For Maria Montessori, play is a fragment of space and time situated between the individual and the world where a child builds up his own self as well as his representation of the world. This is why it is such an essential activity. Space is decisive – in the sphere of the local community, in a spatial context adapted to new ways of life, the playing out of school is a form of childhood survival.

The Sarajevo story shows education is turned into play. This is also a détournement in the relation between these two programmatic activities in architecture. Play had never been on the functional agenda of urban planning unless it had noble objectives – the instillation of values, otherwise it was considered a disturbing, unsocial activity whose disorders – noise and dirt, should be avoided. Playful inclinations of children had to be civilised into play that teaches respectable behaviour.

In the CIAM congresses recreation figures among the four dimensions of the functionalist city: living, working, recreation and transport. This doesn’t explicitly imply children, rather the dweller in general, with recreation as time off work. In the first congress after WWII, CIAM 6, recreation is referred to as ‘the cultivation of mind and body’; the spatial contours of leisure activity are not defined beyond the aspects of open air and green spaces. It is not until the 1951 post-war congress, CIAM 8, The Heart of the City: Towards the Humanisation of Urban Life, that activities pertaining to the public sphere are more clearly put. The new definition of the heart, the core of the city, tries to overcome the much-criticised modernist antihumanistic programmatic city to create liveable environments in neighbourhood units with social, psycho-social and spiritual functions.

on site review 44 : play 13

Amina Avdagi ć

After WWII, reconstruction was not only concerned with the rebuilding of edifices but with the laying down of the foundations of a new society. Children led by example: bombsites scattered across Europe became their informal playgrounds with the basic elements they needed: scrap, loose topography, no grass to care about and no keepers to reprimand them, opening the way to an unprecedented venue: a space made exclusively for the purpose of play.

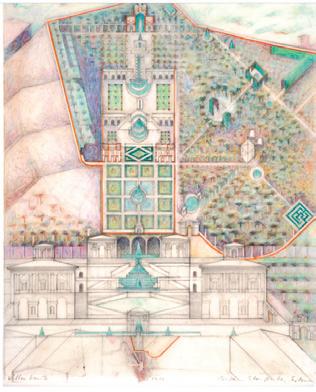

Emdrup, on the outskirts of Copenhagen, 1943 under Nazi occupation: parents had asked for a children’s play space in which activities would not appear suspicious to German soldiers. Dan Fink, an architect with the Emdrupvænge housing estate, commissioned a playground from the landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen in collaboration with the educator Hans Dragehjelm, the inventor of the sandbox, and the pedagogue John Bertelsen. Sørensen was inspired by the simplicity of children ‘messing around’ in bombsites with objets trouvés. He proposed a space to foster a similar action, putting at the disposal of children elements to be manipulated, touched and transformed. This was a transgression of the idea (in place from the eighteenth to the early twentieth century) that associated play with a natural and healthy environment. Sørensen designed an artificial, contaminated nature, where children like those in rural areas, have at their disposal scrap elements of play, but this time associated with urban life.

The director of the playground, John Bertelsen, called it a junk playground, inspiring the landscape architect Lady Allen of Hurtwood in the recovery of London bombsites after the Blitz. It was an opportunity to recycle spaces left free in the re-building process, not for construction, but as free space for kids whose numbers were growing and had no place to play. Junk was not a well-received label for these places so Lady Allen of Hurtwood re-named them adventurous playgrounds. Leila Berg, in her book Look at the Children,1 gives a description of the effect these playgrounds had on adults: ‘I once passed an adventure playground where five or six boys of twelve or so were climbing some high ramshackle construction, so high that it was very visible above the fence – a mistake to be paid for, as all adventure playground workers know – when a man stopped, horrified. He could scarcely believe his eyes. A policeman on the corner was leaning on the bonnet of a car, making notes. The man walked swiftly up, ‘Officer!’ he said. ‘Look!’ The man waved his umbrella; he was incoherent ’Look!’

‘Look at what?’ said the policeman with deliberate weight.

‘Those boys! Look! They’re climbing!’

‘They’re allowed to, sir’ said the policeman. ‘It’s their playground.’

‘But…!’

‘If you don’t mind sir, I’m busy here.’

‘But – they’re climbing!’

‘I know, sir. There is nothing I can do, sir.’

‘But – they’re climbing! It’s fantastic! Disgraceful! Appalling!’

It was also on a bomb site in 1947 that Aldo Van Eyck built his first playground in Amsterdam. On Bertelmanplein he introduced a sandpit, posts of different heights pitched in the pavement and scattered in the plaza, and jumping stones that were first put in the sandpit but later disposed in the surrounding area by Van Eyck himself. The success was such that parents sent letters to the municipality asking for more of these in town. Play as a programmatic component in planning, took advantage of leftover, in-between spaces that destruction laid bare and were lying expectant.

Children’s play became present in public space; more than 700 playgrounds scattered in the city, were designed over 30 years by Aldo Van Eyck. Working in these liminal places, Van Eyck recovered the element of the street as the first public space children appropriated. The street has always been their first extramuros beyond the house, where they felt free to wander and mix with adult life. The indefinite limits of the playgrounds in between buildings and the abstract geometric forms composing the elements of play, engaged children’s imagination but also were absorbed by cityscape almost as if the playgrough was urban furniture found on the street. Once again, we are dealing with the idea of found objects along the way, scrap in the street that can be played out in multiple ways by children.

All this reappears in the importance of the street for children during the war in Sarajevo; it was their way to school, but also an adventurous itinerary. Its elements played a major role in their narratives; the shade of the towering residential building, the corner that was safe, the place that was denied by the snipers, the play against these rules. In the words of Leila Berg:

‘Our street is full of drama. We lived in it. It was our territory. Every stage of our growth was marked on it, our wonderment, our terror, our triumphs, our deprivations, our compensations, our hate and our love.’ 2

In post-war architecture of the Athens’ Charter, elements of circulation or transport, such as the street, were reinterpreted. The street was especially revisited by architects such as the Smithsons who wrote about their Golden Lane housing: ‘the street is an extension of the house; in it children learn for the first time of the world outside the family; it is a microcosmic world in which the street games change with the seasons and the hours are reflected in the cycle of street.’ 3

After WWII in Yugoslavia there was an urgent need for housing. Early large scale social housing estates constituted neighbourhoods on their own, where communal facilities

1 Berg, Leila. Look at kids. Penguin Books, 1972. p 68

2 Ibid. p 44

3 Resta, Giusepe & Dicuonzo, Fabiana. “Playgrounds as meeting places: Post-war experimentations and contemporary perspectives on the design of in-between areas in residential complexes”. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios, no. 47, 2023. Open Edition Journals, https://journals.openedition.org/cidades/7771

on site review 44 : play © 14

Darine Choueiri

were always provided, always a kindergarten and a primary school. Circulation was clearly differentiated – motorised vehicles often relegated to the periphery of the settlement while pedestrians move freely in generous common areas. Depending on the settlements’ typology, these communal spaces were often large scale green areas, or interstitial spaces between residential blocks. In their design and scale they were thought of as spaces of conviviality for an intergenerational public. Pedestrian paths, still considered an extension of school and kindergarten perimeters, are never closed. Children always have access to the extramuros zone of the school where the play area is located, even on weekends. It is probably through this sense of community, of feeling safe in the streets of the neighbourhood and knowing it well, that children eagerly found their way to the punkts, with the help of the objets trouvés on the street.

the aesthetic of play, replayed

The year of the last CIAM congress coincided with that of the Declaration of the Rights of the Children on the 20th November 1959, where play and recreation appear as a right in Principle 7:

‘The child is entitled to receive education, which shall be free and compulsory, at least in the elementary stages. He shall be given an education which will promote his general culture and enable him, on a basis of equal opportunity, to develop his abilities, his individual judgement, and his sense of moral and social responsibility, and to become a useful member of society.

The best interests of the child shall be the guiding principle of those responsible for his education and guidance; that responsibility lies in the first place with his parents.

These operate at both the

4 Unesco Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000064848

5 Caillois, Roger. Man, Play, and Games. Free Press of Glencoe, 1961, pp 9-10

The child shall have full opportunity for play and recreation, which should be directed to the same purposes as education; society and the public authorities, shall endeavour to promote the enjoyment of this right.’4

Even if play is still an annex to education, it is nevertheless considered as an autonomous activity, freed of behavioural codes. It shares the same purposes as education: ‘to enable him, on a basis of equal opportunity, to develop his abilities, his individual judgement, and his sense of moral and social responsibility, and to become a useful member of society’.

In junk playgrounds this childhood emancipation was achieved precisely because of its anti-authoritarian aspect. It is relevant to note that Johan Bertelsen, apart from being the pedagogue and playleader in the playground, was an active member of the Danish Resistance against the Nazi occupation. His views of a non-authoritarian, non-fascist form of life, must have imbued the atmosphere of play in the playground. Schooling under siege was a playing out of this anti-authoritarian response to the belligerents waging war against Sarajevo. The dangerous trip to school implicated children, in that they became equal actors along with teachers in the task of schooling. A whole playful set up was put in place as an act of resistance: the school radio, mathematical competitions, school magazines were launched, even a prom party.

The act of still going to school, possibly superfluous in the context of war, was defiant and echoes one of the components of play according to Caillois, the make-believe. ‘Make-believe: accompanied by a special awareness of a second reality or of a unreality.’ 5 Within the limits of the Sarajevo siege, a geography of movement, a dance of freedom, was created by kids and teachers going to school.

15

Drawing of the blue routes that constituted breaches during the siege that allowed entry and exit from the city.

scale of the city and the scale of the neighbourhood punkt

Thirty years later, I decided to walk this invisible geometry, or more precisely, fragments of it that weren’t forgotten. Almost 300 unrecorded punkts existed in besieged Sarajevo. I ended up with a map retracing the itinerary of three teachers to the punkts. It was impossible to map the trips of children, there were so many of them; they still escape any authority, even the one of representation.

Along the teacher’s itinerary, I was walking through unimportant, trivial parts of town, between blocks in the large housing settlements, sometimes on the backside of the city. Given the overwhelming importance of Ottoman and AustroHungarian architectural heritage to the detriment of that of the Yugoslav socialist period, these are considered the nonaesthetic parts of the city. My own walk, in that sense, was a kind of resistance to dominant aesthetics in the city of Sarajevo, where the architecture of everday life in the housing settlements is invisible and merged with the urban context almost to the point of disappearance.

This resounds with Aldo Van Eyck’s playgrounds melting into the city – an invisible architecture that is, and was during the seige, the scenery of play. The playing out of school used its own aesthetics, or rather anti-aesthetics, of detoured objects and architectures.

Caillois describes play as unproductive, ‘creating neither goods, nor wealth, nor new elements of any kind; and except for the exchange of property among players, ending in a situation identical to that prevailing at the beginning of the game.’6

There is no sign of it taking place, apart from the collective memory of this generation, kept in old school books and washed out photos. Play is unproductive and gathers unproductive objects found in these war playgrounds, such as defused mortars.

When Robert Rauschenberg went to study art at Black Mountain College after WWII, Merce Cunningham said, ‘He made this object out of sticks of wood he found in the street, pieces of newspaper, some plastic. There were some comic strips on it. There were ribbons hanging, and you could go through it or around it or even underneath it. I thought it was beautiful. The colour was so extravagant with all of these materials he’d found in the street.

Rauschenberg began creating works out of found objects when, like other artists of his generation, he was looking for a way to move beyond abstract expressionism […]. These objects created of found fragments, inaugurated the ready-made in art as a critical attitude towards the prevailing aesthetics of arts. By repositioning them they are stripped of their original significance and given a new one. 7

Berg, Leila. Look at kids. Penguin Books, 1972, p. 120. ‘Fantasy is an exploration of living reality, and play a rehearsal of living reality, and we use them both as tools of growth that will help us first understand our reality, and then help us shape it with awareness and competence.’

Rauschenberg would have been fond of Čedo’s photo. In it, the order of representation is completely inverted: the bomb is totally defused, its meaning to be re-invented. This is the rewriting of war by the children, the winning of the battle: they fought it, through play, by the make-believe of living, by detouring its spatial field and objects, like this mortar in arms on a sunny day. They played it out in their own junk playground. And what is play but a ‘rehearsal of living reality’?8 £

on site review 44 : play © 16

6 Ibid.

7 ‘Rauschenberg Shifted Path of American Art’. All things Considered, NPR News: https://www.npr.org/templates/ story/story.php?storyId=90411572

8

above, playground along Marka Marulića Street.

left, the playground area in today’s Alipašino Polje settlement

below, open playground in an interstitial area in Čengić Vila housing settlement.

Darine Choueiri

Darine Choueiri

In the MAXXI of Rome, there was a recent exhibition of Ricardo Dalisi’s work. Especially striking are the workshops Dalisi and his students of Napoli’s Faculty of Architecture Federico II did with the children in Naples, in the area of Rione Traino (1971-74), a district that arose during the post-war reconstruction of social housing in Italy and was suffering from lack of amenities and criminality. The photos in black and white taken by Mimmo Jodice of the children and the structures they were building up, playing with or climbing on, first came to my mind when looking at the children of Gaza, today, hanging and swaying on electrical cables that lie useless after the besieged city is plunged in blackout.

It seems that play, historically, is most creative in an extreme situation, a context in which scarcity fuels creativity in a deliberate intent to play out the materials at hand. This is what Dalisi, a member of the experimental educational program Global Tools (1973-75) was doing: the making of objects through participation and self-engagement: tecnologia povera, ordinary materials offered as tools for children to shape their environment.

Even in a disruptive situation that endangers their childhood, children seek to play, and to study.

Conjuntos divertidos para distfrutarios eye.on.palestine, instagram:

Near the Egyptian border, displaced children use electrical wires to play with, amid the complete blackout in the Gaza Strip since the beginning of the Israeli aggression.

Photos Belal Khaled / @anadoluajansi

This makeshift classroom in Gaza, says it all. Even the children who cannot sit are lining up against the wall, a wall that seems infinite, going beyond the picture frame to reach the thousands of displaced children. The room is insignificant, the architecture is a collective decision to transform it into a classroom, into a living experience. It is a reversal of school scenery, an escape moment, where children are happy to be together, happy to be in this in-between space: the space of play. A glimpse of the Ratna Škola.

Instagram: DarineChoueiri

eye.on.palestine The Palestinian youth Tarek Enabbi teaches children at one of the displaced civilian shelters in Rafah. Via @rabie_noqaira 19 décembre 2023

https://www.instagram.com/p/C1DCTc jgXGf/?igsh=M3p2ajdzc312a21x

on site review 44 : play 17

DARINE CHOUEIRI is an architect-urbanist interested in stories that are embedded spatially. She explores the relation between walking, mapping and the production of narratives, and the power of the built environment in shaping structures of everyday life. atablewithaview.com

postscript

Photographs by Mimmo Jodice, captured from the MAXXI exhibition of Ricardo Dalisi’s work in Naples, 1971-74.

Jean-Franois Pirson at the Venice Biennale, 2018.

child’s play within the Palestinian landscape

SAMER WANAN

A child finds five boxes lying on the ground. Sitting on the floor, small hands randomly pick and choose from the toys placed there: boxes all the same size and yet each feels different as if emotions are imprinted in their materials.

The first box, heavy and dusty, has pieces rattling in it. Opened, the child’s hand runs over the rough surfaces inside, discovering small gaps among its pieces, like dry cracked mud. When the box is tipped all the stone-like parts scatter on the ground, like characters brought to life.

‘Which one is next?’

One is made of old wood, with plants and trees engraved on it. Warm to the touch, this box is hard to open. When it does, the flowers engraved on the outside take on colour and vitality on the inside. Yellow toys inside feel like jellies. All together they are players in a theatre, or in a court.

Another wood box; this one is lighter. Inside, thin clear sheets hang vertically. Black marks on them appear to be a flying bird, maybe a running person, the sheets aligned like a flip-book. Turn the box upside down, they reassemble into a different pile, the birds have a different life as the sheets slide smoothly, shuffled by little hands.

The golden box is next. Cold, dense; metal. Carefully opened, a grainy sticky sand clings to fingers. Digging deeper, tiny buried objects surface and are discovered.

The last toy, a black box, is hiding in the shadows. Laying a hesitant finger on it, the mysterious box opens slowly. ‘But there is nothing in it!’ It is nudged, lights flicker inside. Trying to capture the light, a sharp pain is caught instead, a sting from something very pointed. Unpacked, a fuzzy stuffed object like a stitched glove lies on the floor. The little hand rubs it. It feels magical.

Roland Barthes, in one of his essays in Mythologies, comments on the relationship between children and adults through toys.1 An adult man sees a child as another self, demonstrated in the way that common toys – speaking about French toys at the time of his writing – are ‘a microcosm of the adult world; they are all reduced copies of human objects’. He differentiates between two kinds of toys: invented forms constituted by a set of blocks inviting an open play, and others that are manufactured in a socialised way with a literal meaning, providing no room for the child but to accept the adult world as it is, turning the child into a user rather than a creator. This questions how toys mediate the relationship between generations, or convey generational dynamics. I approach this relationship within the Palestinian context while exploring the role of play and tactility. To do so, a collection of designed artefacts are used as mediators, taking the form of toy boxes and short stories, based in research-by-design methodologies.

The child, in the Palestinian context, is the figure onto whom ancestral generations project their own hopes for liberation and return to homeland. The child, therefore, represents

a future that necessarily includes the liberation of the Palestinian people from suffering. How adults introduce historical events, cultural heritage and identity to children who embody such hopes is a particular case. With a child living in such a violent and oppressive environment, how does it affect their playing patterns and sites of play?

While the formation of a child’s subjectivity depends on the environmental experiences they are living under, there is the possibility of introducing new perceptions of the situation with each generation. Perceptual experiences and hidden narratives within a particular spatial condition and time can be traced by close attention to children’s spatial playing patterns, and material traces they leave behind. A sort of chronicle emerges out of each generation’s forms of play and their toys, carrying the particular tensions that define their environment. Reading it outward will reveal a larger system of forces at play which, in turn, shapes the Palestinian children’s playscape and its material footprints. In an attempt to adapt and appropriate, or even protest against, their imposed environment, the Palestinian child occupies the available small spaces that engulf their own bodies through play

on site review 44 : play © 18

1 Barthes, Roland, Mythologies. Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1957, pp 52-54

Samer Wanan

Studying child’s play counters any idea that play is something minor, of no value, dismissable. This design research project looks at children’s play in violent contexts with a new lens, drawing attention to its material, temporal and architectural dimensions, in search of alternative modes of reading and engagement with a child’s built environment. What can we learn or gain from narrating Palestine through a child’s point of view by bringing attention to their games and playing territories?

In her 2002 novella, Masās (Touch), Adania Shibli portrays a child, overlooked by her elder family members, mirroring the intergenerational social tensions and the internal dynamics of family relations in times of crisis. 2 The interplay between individual subject and collective memory, children’s world with that of the adults, shows the Palestinian situation through the eyes of a child. In a series of fragmentary scenes of the child’s daily encounters, she listens to adults, or witnesses some traumatic event unfolding in front of her eyes while not fully understanding their meaning. Touching on the absurdities of social and political rules, the child finds herself in humorous, sometimes painful, situations when she encounters these rules – living her own intimate world despite feeling the agony in the background. Shibli shows children negotiating the adult world and an imposed environment through play, combining the

factual and fictional, tragedy and irony. She narrates a series of experiential situations through a child’s pre-meditated view – a not-fully-cultured look, revealing a lot about the charged environment and its complex realities. This way, Shibli goes beyond the interiority of everyday life to reach the interiority of the child herself when encountering harsh spatial conditions and social relationships in the family. 3 Shibli’s novella was written in the particular context of the Second Intifada; prevailing anxieties of that time reflect Palestinian fragmented identity and alienation of children in the third or fourth generation after el-Nakba.4

In this project, fragments and residual traces of daily life construct constellations of images, texts and relics related to particular Palestinian conditions at certain times. 5 These assemblages work as material thinking experiments in dialogue with the interiority of the child and the subjectivities of anyone who interacts with the boxes. Though bounded by the edges of the box, situated material objects and charged relics reveal relationships with larger contexts and real-world spatial conditions. There is a reciprocal relationship between miniature toys inside each box and distant inaccessible places and times.

all images Samer Wanan

2 Shibli, Adania. Touch. translated by Paula Haydar. Northampton MA: Interlink Publishing, 2013

3 In Arabic, the word Masā s literally means to be touched by devils or magic, and hence, being mentally affected to the point of insanity, in Arabic: jonna – the state of seeing, thinking and imagining reality in a different way than it really is. The word is also linked to love and poetry in Arabic culture to connotate a person being touched by love. In a sense, it reaches metaphysical, psychological and mental levels to mean touching the soul.

4 The Palestinian story can be narrated as a series of vignettes in relation to its generations. Jīl, means a generation when a group of people inhabits a space and a time frame within a narrative, primarily during their childhood. In the Palestinian case, we say jīl qabl elNakba (prior to the 1948 catastrophe), jīl el-Nakba (the generation who witnessed the 1948 Palestinian catastrophe and the aftermath of displacement), jīl al-fida’iyin (post-1967 ‘Naksa’ era and the launch of armed struggle), jīl el-intifada I (post-1987 uprising), jīl el-intifada II (post-2000 uprising).

The common thread among all five generations is the Palestinian aspiration for liberation and justice, though with different approaches to achieve this ultimate goal and the not-yet-attainable future. Each generation sees the next one, their children, as the source and symbol of hope, believing that they will continue their struggle to be called jīl el-tahrir (the generation of liberation). The word tahrir carries ideas of freedom and futurity within its folds, a myriad of possibilities to speculate about and (re)write the end of the open-ended story. It is not a coincidence that the word for editing a text and re-writing a story in Arabic is also tahrir

5 In Walter Benjamin’s sense - one interested in the refuse of history, of modernity, of the city, see Chapter 10 ‘Rag-picking: The Arcades Project’ in Walter Benjamin’s Archive: images, texts, signs Verso Books, 2015.

on site review 44 : play 19

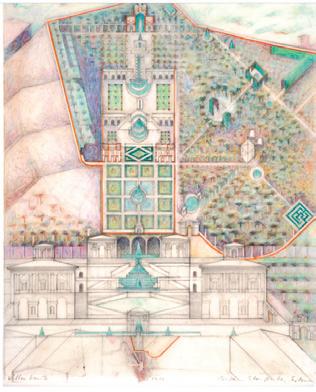

Forest Box explores colonial forestation and the politics of plantation in the Palestinian landscape.

Shadow Box explores Palestinian folklore and folktales and their potential to inform the relationships of land to place.

Olympics Box explores borders and their environments within the Palestinian landscape. Acetate sheets held by 3D-printed holder inside a thin wood box. 21 x 15 x 4 cm

all images Samer Wanan

Sand Box explores archaeology and ownership within the Palestinian context, surveying means and mechanisms. Fragments of card and pins sit in brown sugar, a series of hand sketched drawings folded and attached to the lid with magnets, tin box. 21 x 15 x 4 cm

on site review 44 : play © 20

3D Resin prints and 3D-milled wood pieces with acetate images inside a wood box, 2023. 21 x 15 x 4 cm

Fabric glove with sewing pins placed inside a black wood box. 21 x 15 x 4 cm

Samer Wanan

Play is curated around five topics in a sequence of boxes and short stories representing specific Palestinian conditions. In each of the charged environments, a child’s point of view is adopted, a pre-mediated look that invites exploration which, in turn, makes a multitude of alternative interpretations possible.

To think about this in more detail, let us turn to the Stone Box. The first iteration was made as a gathering device for materials and ideas, specifically the extraction of resources and labour, which eventually led to a particular site and situation. The second time, the box takes the form of a toy that embodies the site’s set of relationships.

The explored site within this box is a contested landscape; the land itself has a unique value due to the sacred association of its stone materials, commonly known as Jerusalem Stone. There is a tradition of extracting material fragments from the Holy Land, which are carried away by tourists and pilgrims as souvenirs and memory objects. Charged relics, in a reliquary box, embody the stories and values of their original geographies. At the same time they raise questions about the destination and reception of this material commodity under its ‘sacred’ status. Stone can move. After being purified — leaving dust, waste and pollution behind — sacred fragments of the Holy Land are placed in synagogues around the world — sites with an indexical connection to the Holy Land through direct contact with its materiality.

With both iterations of the Stone Box, once the lid is closed, the sites of extraction – the quarries surrounding Palestinian communities and from which the stone fragments were gathered, are put in direct contact with places where stone is used as cladding; whether in Jerusalem for the first iteration of the box or in the Israeli settlements in West Bank in the second.

A short story linked to the first Stone Box narrates a fictional city built out of giant stone blocks excavated from different and distant locations. The city has a dual nature with one side depicting everyday life on its surface and the other revealing a magical underground realm. Tourists and pilgrims visit and re-enact historical scenes by entering this hidden realm and touching different stone blocks, each possessing unique spiritual effects and periods of time.

In the second Stone Box a story is reconceived as playing with the box as a toy, putting the child’s body in direct engagement with a surrounding place. By moving the arrangement of miniature paper fragments and stone crumbs inside the box, a larger effect on site takes place. A child is placed in a loop of emotions oscillating between joy and fear, accompanied by a sense of estrangement while struggling to recognise shifting ground after moving any piece in the toy.

on site review 44 : play 21

First iteration of Stone Box opened: 3D wood relief of a cluster of Palestinian stone quarries, attached to a plaster cast lid; miniature 3D cast Jesmonite fragments of Illés Relief model of Jerusalem, 2023. 21 x 15 x 5cm

Stone Box: opened and spread out.

all images Samer Wanan

Second Stone Box: a close-up view of the laser-engraved wooden surface inside the box with varying inscription depths, addressing the relationship between the text of law and its material embodiment on the landscape.

on site review 44 : play © 22

all images Samer Wanan

Second Stone Box: a close-up view into the quarry sites, fragments of stone held on sewing pins, as are paper flags with the Arabic names of Palestinian villages and towns near the quarries.

Second iteration of Stone Box: top view of the box with the lid open where sites of extraction (bottom) are put in touch with construction sites (top), mediated by fragments of stone collected from the quarries. 2023

Samer Wanan

Short fictional stories mobilise the material construction of these toyboxes. Like Stone Box, each of the other boxes imagines a scenario they would unravel in the subjectivity of the child at play in a particular spatial or architectural situation. Besides the representation of distant times and inaccessible places, the constellations of objects inside the boxes have the capacity to generate effects that extend beyond their boundaries. They collect things inside as much as they project out meanings. These boxes, their objects and stories, are tangible and intangible articulations of Palestinian collective memory. The child is able to re-order things to construct an identity and a personal relationship with home, family and the collective. Play, in this way, acts as a driver for cultural construction.

One can read the five boxes as a series of little explorations and speculations. Though constructed as toys for children, for adults they trigger reflection. Versions of oneself as a child are recovered with a small-scale, manipulable form of play. The boxes lean towards Barthes’s open-ended type of play — an invitation to read Palestinian history and culture in a simultaneously allegorical, tactile and experimental manner.

acknowledgements

I am grateful to my supervisors Professor Mark Dorrian and Dr. Ana Bonet Miro, as well as to Dr Ella Chmielewska for the fruitful discussions during my PhD journey at the University of Edinburgh. This essay would not have been possible without their invaluable input.

SAMER WANAN is currently undertaking an Architecture by Design PhD at Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, part of Edinburgh College of Art, the University of Edinburgh. He holds degrees in architecture from Birzeit University and Newcastle University.

on site review 44 : play 23

£

The constellations of charged boxes and toys create a field that plays out in both directions, from the outside world in and from the inside world of each child, out.

all images Samer Wanan

(for)play and wordplay

YVONNE SINGER

Even as a child it was hard to play except for times at the seashore digging in the sand to the accompaniment of the reassuring roar of ocean waves. As an immigrant child, new to the English language, the game of ‘step on a crack, break your mother’s back’ was an opportunity to be singled out as the only one to step on a crack. It was the same with Hide and Seek or variations of it, another game that is fraught if you do not know the rules and the language.

This is the paradox of play, serious but trivial, innocent but fraught with danger.

So what is the meaning of play? I thought the word and its meaning was straightforward until I began the research. The Random House Dictionary has three full columns on the word play. And there are many theories about play, from psychoanalyst D W Winnicott to game theory.

There are many taxonomies of play: physical play, social play, constructive play, fantasy play, solitary play, parallel play, group play.

Colloquial applications of the word play demonstrate its multidimensionality:

word play, foul play, playful, co-play, f0oreplay, playoff. Play one’s card, play the game, play on.

Play both ends against the middle, play fast and loose, play tricks, playing with fire, play a hunch.

Play by ear, play acting, make a play for, play of light, the play’s the thing, play for time. Playbook, playback, playbill. Playpen, plaything, Playhouse, playground, play by play, playing the field. Played out, playboy, playmate, play offs. Play along.

For me, play is art-making with ideas, dreams, images, words and any materials and forms that serve my purpose. Certainly my play is informed by my personal story and the aesthetic and educational environment that shaped me, but within that arena I can make my own rules and speak in my own voice. Here in this private world, I can be crazy, pragmatic, stupid, unrealistic, impossible, sentimental, nostalgic, depressed, unpredictable, bewildering — that’s all part of the process.

I offer this linguistic and artistic expression of play as it relates to the primal gesture of drawing

drawing as sign drawing as action drawing as thought

drawing a line drawing as a language the syntax of line

And exploring drawing as gesture, as object, as metaphor, as duration, as boundary, I did a long blind drawing, a 20’ scroll, one of many elements in the 1988 installation Contradictions/ Possibilities at Niagara Artists Centre, St Catharines.