10 minute read

housing for all

Ron Wickman

Affordable housing is a complex issue and so difficult to achieve. While a history of racial and social discrimination can be highlighted in obvious ways, with urban planning and architecture it occurs in much more subtle ways. Bureaucratic and free market system beliefs, including zoning bylaws and strategic community planning have a history of frustrating effective affordable housing. Add accessibility and the challenges become greater. Too many people live in poverty, especially true of those with disabilities. Simply put, there is an urgent need to have more housing stock that sits outside the market economy.

For architects, affordable and accessible housing can only effectively work when we want to learn more and get better at our craft in this area of design. I spend every day speaking to, and working with, at least one person with a disability. My practice focuses on small projects where the end users participate in the design process; they are not just asked to comment on prototypes or fait accomplis from the architect. The beauty in this architecture comes from recognising as many people as possible working with an experiential design process for a better architecture. Fundamentally, a well-designed built environment must create a framework for people to live their best lives.

accessible architecture is just good design

We cannot rely on accessibility guides, standards and codes alone if we are to create an architecture that is more accessible and inclusive for anyone and everyone. This is not just a technical issue but one that offers us the choice to invest ourselves emotionally in a design philosophy that focuses on the toughest populations with a range of disabilities to make the most accessible built environment possible.

Specific everyday users, site conditions and the cultural context of a particular region, plus the history and unique characteristics of accessible architecture, will move us on from the medical model of disability which is to fix individuals so that their disabilities appear normal. Instead they point to a social model that tailors built environments to meet everyone and anyone’s needs, including those with physical, visual, hearing and sensory limitations. At its most basic, curb ramps, no-step building entrances, good interior lighting, acoustics and wayfinding strategies should be the barest of minimums.

I have been around disability my entire life – in architecture school, in my mind, I would wheel through my designs. My father was a paraplegic and used a manual wheelchair; he was a City of Edmonton councillor for nine years and a Liberal MLA for 12 years at a time when there was no accessibility in the built environment and very few human rights for a person with disabilities. He and his colleagues often acted out of desperation to force change, knowing that the political climate is not always on the side of social

justice. He became a political leader and decision maker to help those most marginalised in our society. We both consider poverty and low social status as disabilities. Affordable housing struggles to accommodate either persons with disabilities or those who are homeless. Our most vulnerable people are left behind in the accomodation of the needs of a perceived majority. We must work hard to shake the current order of society where wealth and power dictate.

what is normal?

Building standards and requirements are too often based on the idea of a normal person who is inevitably a young able-bodied man with excellent overall mobility. A better understanding of people would include those who use mobility devices such as a manual or power wheelchair, people with visual and hearing limitations, people who are neurodivergent, people who are ill, and finally our aging population who may have any combination of these conditions.

The idea of sustainable built environments gathered strength when a critical mass of architects started educating themselves to work on positive solutions to environmental issues, focussing on design solutions that not only create green living but best provide people with positive experiences. We now need a critical mass of architects to promote these same positive experiences for persons with fragilities. Although society relies on architects to focus on accessibility, aesthetics and sustainability, unfortunately law-makers, political decision-makers and investors – from banks to shareholders – are wary of change and new ideas. Profit often comes before people. And yet, paradoxically, architects are the ones challenged by decision-makers and investors to present innovative design solutions. Ultimately it is architects with the power to create this change. Therefore, to get the right answers, we need to ask the right questions about fundamental practices:

1 Accessible architecture commits to participation in the built environment by everyone, despite their age and abilities. Inclusive and sustainable design means social inclusion for everyone, and are integral to the design process right from the start. For example, a compact urban environment, accessible and sustainable, understands that not everyone can drive a car. Accessible architecture offers everyone choices for independent movement. Living on equal terms with everyone else, starts here. When we think about housing design, choices for how we want to live are essential.

2 Architects are trained to be problem solvers and to think outside the box — we can come up with practical and beautiful solutions no matter what the design issue is. For this to happen, especially when it comes to affordable and accessible housing, we need to understand culture and society, not just science and technology. Education is the key. We can start by encouraging such thinking in schools of architecture and other design disciplines. Frankly, we must emotionally invest more of ourselves in truly affordable and accessible housing that benefits us all — not just us as individuals, but us as a society.

3 The best design projects start with great collaborations. This means that those who control the design project must be willing to take a leap of faith design journey with the architects and designers committed to producing a beautiful building or space that accommodates the largest community possible. Hope and energy are at the core of this design philosophy.

case studies

I’m showing here two affordable and accessible housing projects where I was the architect. Both projects were funded in part through government grants and both projects have been designed primarily for persons who are First Nations.

Ambrose Place in Edmonton (Off-Reserve) primarily serves individuals and couples who are experiencing homelessness and are of Aboriginal descent.

Métis Community Elder’s Housing in Lac Ste. Anne (On-Reserve), is designed to afford local residents safety and independent access to housing as they age in place.

We worked very closely with the client communities reinforcing their active engagement right from the beginning of the design process and beyond. Both projects focused on three key building design features as the starting point: no-step entrances, accessible vertical circulation and wheelchair accessible bathrooms. Further design development considered the needs of as many people with differing disabilities as possible allowing us to develop overall solutions that are not only functionally effective but more affordable.

These two affordable and accessible housing examples demonstrate that things only need to be slightly different to be more inclusive. They highlight that meaningful participation by all of those involved is the most effective way to positive outcomes. This requires a deeper understanding of the issues important not only to the architects but to the people who will occupy the building including individuals with disabilities, to those responsible for development and building code requirements, and to those funding the project. It takes the collective creativity and willpower of a community to build a community.

ambrose place

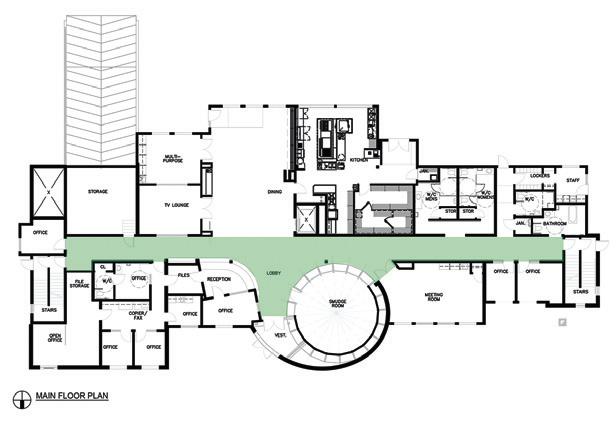

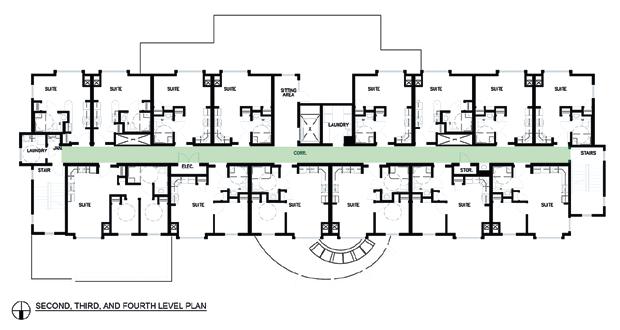

Ambrose Place is a four-storey apartment building containing 42 dwellings and a Ceremony Room that is central to the design concept and the most decorated and detailed part of the building. All 42 dwellings have bathrooms designed as wetrooms with curbless shower areas that can accommodate any number of residents, including those who use wheelchairs. Kitchens have adaptable features such as the 10 dwellings that have countertops that can be easily adjusted to differing heights.

The building is strategically located in the inner city close to many important amenities and services which are part of the individual residents’ daily lives. It was also designed at a scale to fit within in urban context. Greater affordability was achieved through simple and straightforward design and the elimination of overly fussy and complicated construction details. Most importantly, the housing design focused upon improving the quality of an individual’s life, health and well-being, looking beyond the labels of addiction or disability to look at the whole person including their history, culture and their mental, physical and spiritual needs. The beauty of this project is not just visual, but lies in its ability to allow its residents to live with grace, safety and confidence.

lac ste anne métis elders community

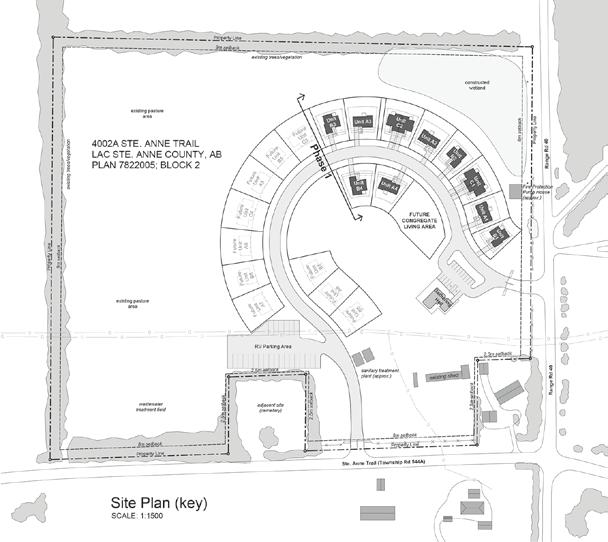

The Lac Ste Anne Métis Elders Community is located approximately an hour away by car from Edmonton. The community is designed to be constructed in phases – currently under construction are eight single family houses and two duplexes. When complete, the community will house 30 residents in single family houses, duplexes and in a long-term care residence, with a gathering hall at the centre of the community. The Elders Community is close tor the core of the Lac Ste Anne Settlement area, allowing Elders to continue their involvement in social and community events, to be nearby other language speakers, and to benefit from traditional land use and cultural practices such as fishing and hunting. The design intent honours the community’s collective history and culture as stewards of the land, and it looks to sustainable design principles that focus on critical strategies, from fire-protection to allowing Elders to age in place.

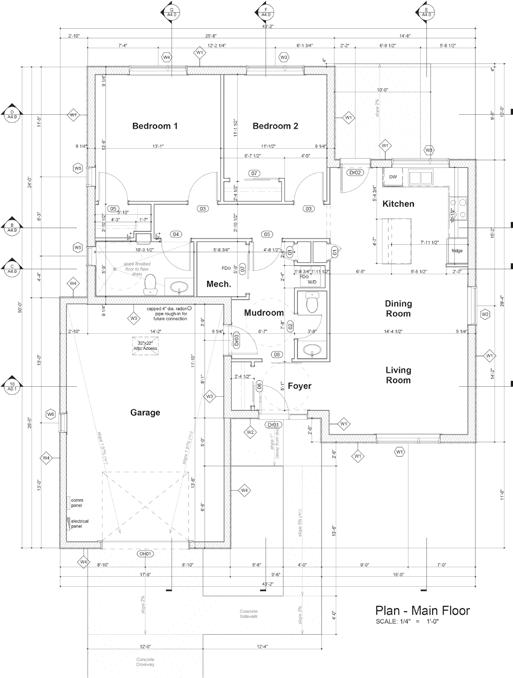

Collaboration with engineers and contractors began at the design stage, especially with the civil engineers. As great attention was given to the need for no-step entrances to the dwellings, the land was sculpted in gently sloping sidewalks everywhere. Just as in Ambrose Place, all bathrooms are wetrooms with wheelin, curbless shower areas, and all kitchens are designed to be adaptable to easy modifications for individuals who may use wheelchairs. Affordability was considered a long-term issue and therefore extra expenses were made at the initial construction phase to save money in the future. For example, the heating and cooling system is not powered by gas, but electricity, and the building envelope uses prefabricated panels that provide high levels of insulation value. The adaptable and accessible design features for the dwellings added very little extra cost (maybe 1% extra) but will save thousands of future dollars and energy waste by not requiring major modifications for accessibility.

Ron Wickman is an Edmonton architect, engaged locally and internationally with participatory and inclusive design. www.ronwickmanarchitect.ca