A FOREST FA

How the Canadian governmen

Gaps in federal legislation have masked the logging industry’s destructive effect o

I

f the Liberal government’s favourite colour isn’t red, then it’s green. A quick scroll through the Liberal Party of Canada’s social media pages displays Justin Trudeau and his cabinet posing in front of sprawling marine vistas and dramatic mountain ranges. One of their most buzzworthy platform goals of the last election was the “two billion trees over 10 years” — an ambitious plan to plant a net additional two billion trees to offset deforestation and increase carbon holdings. Even amidst the continuing pandemic, Trudeau said in an August news conference that “this is our chance to build a more resilient Canada: a Canada that is healthier and safer, greener and more competitive.” The balance of environmental and economic goals is an increasingly significant arena for Canadian politics. More voters are recognizing the reality of their unsustainable lives, and in turn, the Liberal government is recognizing the political value of emphasizing their environmental priorities. The prevailing narrative of being ecologically and financially focused helps them resonate with constituents from coast to coast. Especially in modern times, placing green policy at the forefront of government activity is a calculated and effective decision. However, with climate and scien-

tific deadlines looming, we can’t allow any more illusions or empty words. How much of what the Liberal government says is inadequate pageantry, and how much is real, actionable change? The Canadian boreal forest is inconceivably vast, covering more than one billion acres, and stretching across the nation from the shores of British Columbia to the cliffs of Newfoundland. The forest is a haven to delicate lichens, impenetrable brush cover, ancient trees, and mysterious wetlands. According to Hinterland Who’s Who, it is home to over 80 percent of Canada’s Indigenous peoples, whose rich heritage has been wholly entwined with the forest for millennia. It is an environment of incredible scientific, economic, cultural, and spiritual value, and it is also emerging as one of our best solutions to the climate crisis. The boreal forest is a phenomenal carbon storehouse, like many other forested ecosystems in the world. The process of photosynthesis — a plant’s ability to suck carbon dioxide from the air and convert it into oxygen — allows boreal plants to store massive amounts of carbon in their leaves, branches, and roots, which make up their biomass. As this biomass degrades over the plant’s lifetime, the carbon slips slowly into the soil, where another massive carbon

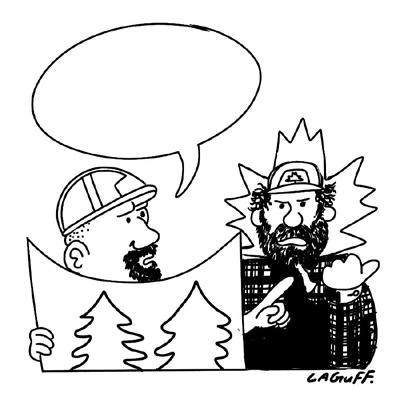

Cut 'em all down.

holding exists. The same concept exists in the abundant wetlands which, due to their water-rich and oxygen-poor conditions, are also excellent at keeping carbon locked deep within their decaying slime. What’s special about the Canadian boreal forest is that it is very cold and has thousands — if not millions — of wetlands, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council’s (NRDC) 2018 Pandora’s Box report. The report outlines that these two factors ensure atmospheric carbon is comfortably sequestered in the forest for a long period of time, essentially restricting its exodus into the air, where the carbon dioxide absorbs heat trying to escape the planet. This heat absorption scalds the atmosphere, which results in gradual worldwide warming and accelerated change of the global climate. The report further outlines that, in total, every part of the Canadian boreal forest (including its soils, biomass, wetlands) holds an estimated 306.6 billion tons of carbon stock, and is therefore preventing those 306.6 billion tons from entering the atmosphere. The magnitude of this is almost incomprehensible. To compare, a single car emits only 4.6 tons of carbon dioxide a year, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, which is a trillionth of a percent of the stored carbon found in the boreal forest. A section in The Logging Loophole, a report published in July by the NRDC, Environmental Defense, and Nature Canada on the Canadian logging industries, states that “a pervasive and misguided narrative, based on selective science and misleading assumptions, has made its way into federal and provincial policy in Canada.” The report details the fallacies of Canadian carbon emission reporting, and how the Canadian government and the logging industry have unknowingly joined forces to paint a sustainable image of Canadian logging. Jennifer Skene is the principal author of the report and a Yale-educated environmental law fellow that works with the NRDC. In the report she writes that for years, the NRDC has been

concerned with the way Canada has been ignoring carbon emissions from its boreal forests, and neglecting to count them in carbon accounting reports. The logging industries have seized upon this opportunity, and have used these discrepancies to bolster their claims that logging is climate-friendly.

The entire process of sequestration can be disrupted when forests are harvested in incorret ways. Canada uses a model rather than direct data to calculate its forest emission data, and uses the findings to make assumptions about uncertainties. According to Skene's report, one of the largest, most damaging assumptions made by provincial governments is that every single tree cut down grows back. Any child working on a school project growing sunflowers can tell you this is not true: nature does not have a 100 percent success rate. However, this appears to be one assumption that Canada's climate policies were written on, and one that is dangerously contra-science. Even if this assumption was true, and every tree removed was replaced by another exact copy, this harvest would still signify a release of carbon. According to Skene’s report, the carbon sequestration abilities of the boreal forest are related to age, as trees do not stop isolating carbon as their lives continue. Older trees hold more carbon, and it takes decades for newly planted trees to reach the original level of carbon holdings. Even if every felled tree had a healthy replacement, the loss of the original tree means a massive initial expulsion of carbon dioxide into our atmosphere, and a slow recovery. Old-growth — or intact forests — are forests that remain largely untouched by human footprint, and contain most of these older trees that are so good at holding carbon. The “one tree replaces anoth-

er” concept is also a very narrow viewpoint as the entire ecosystem is not being considered. We have seen how decaying biomass in the soils and wetlands are remarkable keepers of carbon. The Pandora’s Box report states that anthropogenic activities such as harvesting and clear-cutting upset the careful balance between organisms, no matter the scale. The entire process of carbon sequestration can be disrupted when forests are harvested in incorrect ways: by removing too many trees, disturbing the forest floor, or removing too much of the biomass under trees. Any of these actions can cause changes in sunlight and temperature which can disrupt the entire ecosystem and can lead to stored carbon chemically transitioning to carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide then escapes and rises into the atmosphere, adding to Canada’s carbon footprint. Conservation is seen as a long-term plan. However, given the extent of the climate crisis and the lack of breathing room that world powers have to operate in, this is not the case. Conserving intact forests is a short-term solution. The Liberal government’s promise of planting two billion trees over ten years, while commendable, carries next to no benefits in the time frame that we need them. However, keeping forests intact and untouched ensures that the carbon stored in them will not get released into the atmosphere. Tenaciously holding onto these forests with the goal of keeping them out of danger is one of our best solutions to the climate crisis. It’s cheap, easy, and feasible — criteria that every government looks for. A video entitled Harvesting in the boreal forest on the Natural Resources Canada (NRC) Youtube channel follows scientist Doug Pitt as he talks earnestly about the benefits of clearcutting. “One of the primary goals of our silviculture is to emulate natural disturbances ... species such as jack pine, black spruce, and aspen have all evolved requiring more or less full sunlight to regenerate and grow properly,” Pitt says. His voice is interspersed with swooping helicopter shots of