6 minute read

WATER ON COURSES

some thoughts from John Colls* and Geoff Peck*

[*This article is a result of Geoff and John chewing the fat in Queensland during the recent Australian Championships carnival, reviewing evolution in the O-world since they first got into it in Scotland more than 40 years ago. Geoff was the first Brit to break into the world elite of Scandinavians and central Europeans back in the 1970s: he has been at the pointy end of the sport ever since. John was instrumental in setting up the Scottish 6 Days in 1976 and regularly controls one of its race-days, facing issues of scale and complexity that are unknown here in Australia. For example, coping with 500 competitors sounds easy enough – but that’s just on the String Course!!]

We doubt that any experienced orienteer would challenge Andy Hogg’s basic premise (Letters; AO-September ‘08) about the importance of having water available on courses to help heat-stressed competitors.

In conditions which were hotter and more humid than found at most Australian events, organisers of the World Masters in Portugal chose to site water points at convenient, accessible positions. Each was manned by an army cadet with a radio link to base. Medical trucks were similarly positioned.

Thereafter, however, many would argue that the crux of the problem lies with the current Orienteering Australia (OA) rules, in their insistence that water be placed only at a control site or compulsory crossing point. Such a restriction is not only at odds with practice elsewhere in the world (as Andy acknowledges) but is inherently illogical and potentially dangerous.

If (as Andy rightly argues) access to water may be a life saver in hot, dry Australian conditions, then why on earth place it at a control site that a heat-addled competitor may be incapable of finding? From a risk management perspective it is lunacy, especially when – as often happens in those weather conditions where water is most needed – the hapless competitor eventually struggles to the site only to discover that its meagre supply has already been exhausted.

Rather than a spirited defence of existing OA rules and policy, would it not be better to examine where they might be improved?

We believe that there are critical health and safety issues surrounding this topic. They should be worked through methodically and urgently before there is a serious accident where the finger of blame or responsibility may be pointed at OA, but the sport as a whole suffers in terms of public perception. The first key point is to recognise that there are two sets of issues (some running in parallel, others intersecting) that affect competitors and organisers respectively. The event controller should be monitoring both – and insisting on

corrective action where necessary.

For example, from an organiser’s perspective: • why devote large amounts of time and effort to carrying heavy containers of water to remote control sites, when a better outcome could be achieved for a tiny fraction of the same investment? • in particular, why expose volunteer officials to the risk of accident or injury from such back-breaking jobs (perhaps literally so!) when a different approach would render the tasks redundant? • why condone a flawed policy that ‘hides’ vital water at hard-to-find control sites? A defence of ‘it seemed a good idea at the time’ is unlikely to find favour in any legal action resulting from a serious incident. • similarly, why condone a flawed rule (water available every 25 minutes)? Andy emphasises that the 25 minutes is calculated on leading times, a mindset that creates a fundamental problem. If emergency water is needed, it is far more likely to be for competitors who have made major mistakes than for the leaders. By definition, ‘25’ then becomes ‘30’, ‘35’, ‘40’ or more. • even accepting ‘25’ in its current interpretation, the first water on M60 at both the Queensland and the Australian

Championships was two-thirds of the way round the course. With an expected winning time of about 60 minutes, that means an initial 40 minutes without water even for the leaders. So were the relevant officials unaware of OA rules, or did they decide to ignore them? Either way, it raises questions as to why OA is overseeing premier events that breach its own safety rules.

Serious as such problems are, they are not difficult to solve. All that is needed is for OA to adopt the sorts of rules and policies that have been standard practice in the rest of the world for many years.

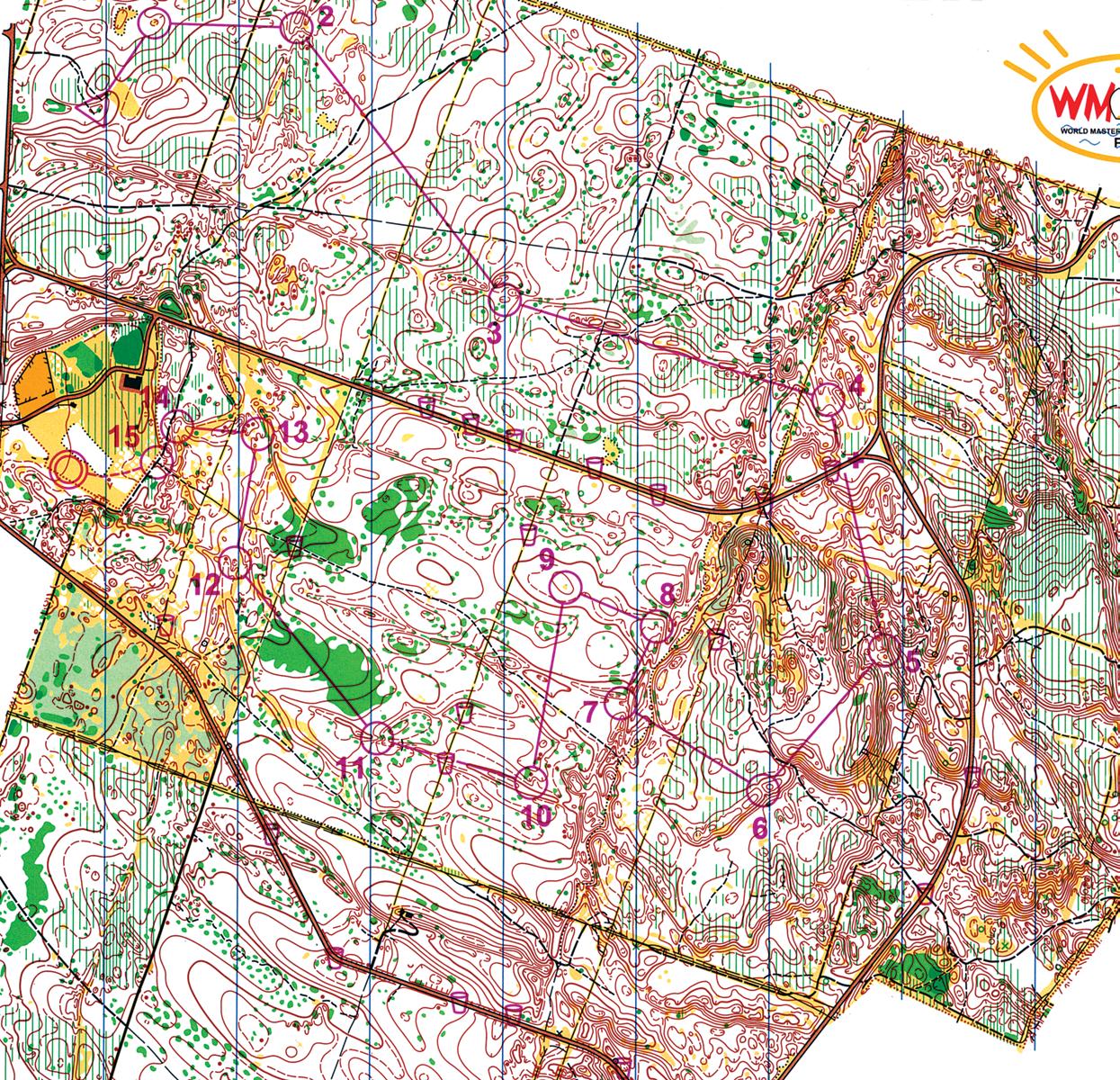

For example, at the Queensland Championships the competition area was bisected by a vehicle track, along which it would have been easy (but for the pesky OA rule!) to place a series of well-stocked water-points at intervals. This is the practice universally adopted at large events overseas, and with good reason. Not only does it make the organiser’s job easier and safer, it provides a better and safer outcome for competitors. If course planning is co-ordinated with the location of the water-points (as it should be), then each and every leg and control site can be chosen purely on technical merit, free of the compromises that are inevitable if some sites have to be chosen with a view to getting water to them. Moreover, if water-points in hot conditions are seen as a special type of First Aid post (as Andy implies), then the corollary is that they must be easily found by anyone whose capacity for rational thought has already been impaired by heat/dehydration. Clearly, a series of water-points strung along a major track meets that criterion.

Of course, many competition areas are such that it is not feasible to use a vehicle to place water at strategic locations, so what best to do then?

The answer, not surprisingly, is that the outcome will depend on a careful analysis of whatever options are realistic for the terrain and weather conditions in question. It may, for example, make sense to set longer courses in hot weather as a series of loops that bring competitors back through ‘spectator’ controls close to the Finish/Assembly where water is adjacent. Additionally, the issue of recommending to competitors that they carry their own water ought to be addressed seriously (not just dismissed as contrary to OA rules). The critical issue for any competitor is that he or she needs to know before the race where water will be available in order to make a personal decision about how best to avoid the risk of dehydration. If that means a recommendation in the event program from organiser/controller that competitors carry their own water, then so be it. Such a clearly defined outcome would be much better than the ambiguities that often prevail at present. Of course, the question of competitor dehydration is not unique to Orienteering. It is common to all endurance sports and we ought therefore to look at medical opinion and at their practices and trends in deciding what is best for our own sport. Broadly speaking, the debate is about where the line should be drawn between what an organiser provides for a competitor and what the competitor takes personal responsibility for. [This is obviously a big topic in its own right - anyone interested should Google on a few key words].