Design May-June 2018

THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

DESIGN REDEFINED

Design May - June 2018

40

A Chair (Not Made) for Sitting As the barriers between art and design dissolve, how should furniture respond to the world around it? By Nikil Saval Photographs by Anthony Cotsifas Set design by Jill Nicholls

46

The House Is Not a Home On the eve of a major exhibition, Marc Camille Chaimowicz, whose art often examines interior spaces, prepares to leave the London flat where he’s lived and worked for 40 years. By Gaby Wood Photographs by Jason Larkin

53

Architecture of Subversion

PHOTOGRAPHS BY MIKAEL OLSSON

2 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

The Swedish island of Gotland is one of those proudly low-key holiday destinations where tradition is upheld and showiness is frowned upon. What, then, explains its recent crop of shockingly contemporary residences? By Nancy Hass Photographs by Mikael Olsson

Page 53 The residence by married architects Hans Murman and Ulla Alberts is wrapped in a scrim printed with life-size photograph of the surrounding juniper trees.

THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

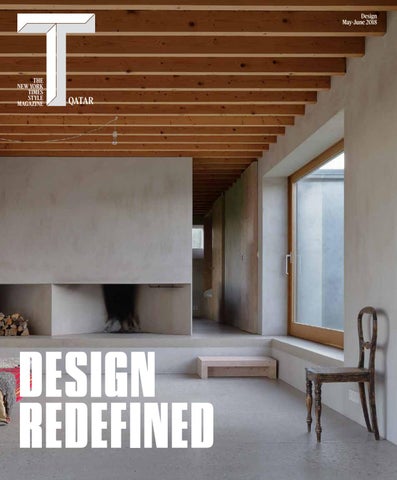

ON THE COVER: To follow the natural curve of the land and avoid blasting into dense rock, Tham, the architect, designed the concrete floors of his near-bare dwelling to rise and fall from room to room. Photograph by Mikael Olsson

3

THINGS

People, Places & Things Crystalline sculptures, men’s scents from Louis Vuitton, a time for twinks and more, Modern bungalows in Portugal, the call of the merman and more.

29 Long considered the gold standard of baking, French pastries are being reimagined with bold colors, strange flavors and blatant disregard for the established rules.

PEOPLE 16

Home in Two Worlds

By Ligaya Mishan Photographs by Patricia Heal Styled by Beverley Hyde

Naina Shah and Abhishek Honawar work between New York and India: she in fashion, he in hospitality. Next, the couple will team up on their own design studio. By Alice Newell-Hanson Photographs by Flora Hanitijo

31

Market Report Embellished sandals. Photographs by Mari Maeda and Yuji Oboshi

33

Page 32

Large timepieces so good you’ll want to sleep in them. Photographs by Anthony Cotsifas Styled by Haidee Findlay-Levin

PLACES Page 35

20

Free Forms Outdoor furniture that’s light as air. Photographs by Leandro Farina Styled by Theresa Rivera

30 Wanderlust

4 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

Rustic and largely unexplored, Upcountry is Maui’s other side of paradise. By John Wogan Photographs by Joe Leavenworth

Bold Bedfellows

60

Of a Kind Artist Tony Oursler’s spiritual ephemera. Illustrations by Aurore de La Morinerie. By Nancy Hass Photograph by Nicholas Calcott

Page 16

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: PHOTOGRAPHS BYANTHONY COTSIFAS; FLORA HANITIJO; PATRICIA HEAL

10

13

People, Places & Things Qatar Paris to Doha; Broadening Horizons; Art in Everything.

14 Our Heritage is Your Heritage Keeping the spirit and traditions of Qatar very much alive, Ramadan, the holiest month in the Islamic calendar, was once again observed across the country.

PEOPLE QATAR 18

Pop Culture Creative Emirati design talent Fatma Al Mulla began documenting cult obsessions among communities in the Gulf and immortalised them in illustrations.

Page 14

Page 104

PLACES QATAR 25

Let's Go For A Walk The UK’s largest UNESCO World Heritage Site sprawls over an impressive 229,200 hectares and is emblematic of one the nation’s favorite pasttimes, walking. By Debrina Aliyah Photo courtesy of Twenty30Forty

Page 19

35

A Mischievous Stitch

6 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

A self-professed off-kilter artist of an unconventional medium teams up with Weekend Max Mara to bring some jazz to formal daywear. By Debrina Aliyah

38

Candy Pastels Pleasant soft shades to match sunkissed summer skin. By Debrina Aliyah

ABOVE: PHOTO COURTESY OF SHERATON GRAND DOHA RESORT & CONVENTION HOTEL; BELOW: TOMMY HILFIGER

THINGS QATAR

Editor in Chief Hanya Yanagihara Creative Director Patrick Li Style Directors David Farber/Men Malina Joseph Gilchrist/Women

Executive Managing Editor Minju Pak Features Director Thessaly La Force

Photography and Video Director Nadia Vellam

Fashion Features Director Alexa Brazilian

Entertainment Director Lauren Tabach-Bank

Design/Interiors Director Tom Delavan

Digital Director Isabel Wilkinson

THE NEW YORK TIMES NEWS SERVICES General Manager: Michael Greenspon Vice President Licensing and Syndication: Alice Ting Vice President, Executive Editor The New York Times News Service & Syndicate: Nancy Lee LICENSED EDITIONS Editorial Director: Anita Patil Deputy Editorial Director: Alexandra Polkinghorn Editorial Coordinator: Ian Carlino Coordinator: Ilaria Parogni

Page 17

PUBLISHER & EDITOR IN CHIEF

SENIOR CORRESPONDENTS

MARKETING AND SALES

ACCOUNTANT

Yousuf Jassem Al Darwish

Karim Emam, Udayan Nag

MANAGER – MARKETING

Pratap Chandran

MANAGING DIRECTOR & CEO

ART

Sakala A Debrass

DISTRIBUTION

Jassem bin Yousuf Al Darwish

SENIOR ART DIRECTOR

ADVERTISE MANAGER

Basanta Pokhrel

COMMERCIAL MANAGER

Mansour ElSheikh

Sony Vellat

Dr. Faisal Fouad

DEPUTY ART DIRECTOR

EVENTS OFFICER

PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICER

Ayush Indrajith

Ghazala Mohammed

Eslam Elmahalawy

EDITORIAL CHIEF EDITOR Ezdihar Ibrahim Ali FASHION EDITOR Debrina Aliyah

PUBLISHED BY

Oryx Publishing & Advertising Co.WLL

P.O. Box 3272; Doha-Qatar, Tel: (+974) 44672139, 44550983, 44671173, 44667584, Fax: (+974) 44550982, Email: info@oryxpublishing.com Website: www.oryxpublishing.com COPYRIGHT INFO T, The New York Times Style Magazine, and the T logo are trademarks of The New York Times Co., NY, NY, USA, and are used under license by Oryx Media, Qatar. Content reproduced from T, The New York Times Style Magazine, copyright The New York Times Co. and/or its contributors 2018 all rights reserved. The views and opinions expressed within T Qatar are not necessarily those of The New York Times Company or those of its contributors.

PHOTO COURTESY OF GEORGIA KOKOLIS

8 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

Embroidery artist Richard Saja

PEOPLE, PLACES & THINGS

Introduces

10 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

Photograph by Adam Kremer Set Design by Jill Nicholls

Informally arranged along the windowsill of Zuza Mengham’s light-filled South London studio is a small collection of crystals and natural stones, from smoky quartz to Himalayan salt. The 29-year-old artist grew up in a new-age-leaning household in Cambridge, England, and is not immune to the sort of thinking you might be more likely to find in L.A. ‘‘It never hurts to have a bit of positive chi,’’ she says. These objects, however, are more significant than they might seem. Over the past few years, Mengham, who studied at Wimbledon College of Arts, has become known for confection-colored tabletop sculptures that echo the multifaceted architecture of crystals. Beneath the sill stands one of Mengham’s latest works: a craggy and asymmetrical obelisk with a translucent, pale pink peak and opaque grayscale layers below. ‘‘I want to create imagined geographies,’’ she says. From afar, the piece looks almost edible, like a slice of geometric cake with a gelatin top. Up close, it’s like a saturated, angular take on a crystal ball: transfixing and otherworldly. And yet Mengham does not ascribe to her creations anything other than aesthetic power. ‘‘They’re man-made,’’ she says, ‘‘which goes entirely against the idea of natural healing or anything like that.’’

Her material-driven practice is focused largely on resin, which many artists use to create mock-ups of sculptures that will ultimately be rendered in metal. Wanting to prove that the material could be more than a substitute, Mengham crafted an early series of iceberg-shaped blocks of resin infused with copper, bronze, iron, slate, marble and salt: a haunting union of the synthetic and modern with the elemental and ancient. For inspiration, Mengham likes to visit the Neolithic tombs scattered across the English countryside, searching for examples of age-old craftsmanship. At last fall’s London Design Fair, she presented pastelcolored totems made of Jesmonite — a composite substance made from gypsum powder and acrylic

resin — and five species of lichen embedded directly onto their surfaces. The contents of her latest series, ‘‘Moom,’’ feature cloudy swirls, achieved by adding squirts of different pigmented resins to those Above: two of Mengham’s already filling Mengham’s one-off Jesmonite and molds. A sculpture’s form is only final lichen sculptures, once dry, and so the maker must cede as well as her speckled Wedge some control to the universe. ‘‘For vase, all 2016. me it’s all about the actual making. It’s a physical procedure, but I’m always working with light and angles, and there’s something quite meditative about that,’’ she says. ‘‘Maybe that subconsciously comes through in the work — it has to have a bit of presence.’’ — Natalia Rachlin

IN 2013, Louis Vuitton took over Les Fontaines Parfumées (below), a coral-colored 17thcentury bastide in the French Riviera town of Grasse, in anticipation of launching its first women’s scents in over 70 years. More recently, master perfumer Jacques Cavallier Belletrud has been toiling away in the elegant building’s top-floor lab on a second major launch — Vuitton’s first-ever men’s colognes, arriving in stores next month. ‘‘Men today are more disruptive, less classical,’’ Cavallier Belletrud says. ‘‘Thirty or 40 years ago, we used very heavy fragrances. Now, it’s more about fruity notes and those in accordance with nature.’’ Indeed, one of the five new scents, L’Immensité, blends the brightness of grapefruit with ginger, while the softer, woody Orage contains notes of iris, patchouli and vetiver. In addition to a certain lightness, the fragrances share a point of inspiration: travel. Many noses speak of olfactory journeys, but at Vuitton, which has made luggage for everyone from 19th-century explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza to Catherine Deneuve, the connection to travel is more than cursory. Trips to southern Italy got Cavallier Belletrud thinking about Calabrian citron, which he combined with Peruvian balsam for Sur la Route (right). ‘‘One must take the time to discover,’’ he says. — Kelly Harris Starting at $240 each. louisvuitton.com.

IT MIGHT SOUND like a Zen koan, but the next Bali is the Bali of old: Increasingly, travelers are moving away from the island’s beachside resorts in search of the lush natural landscapes that made it a destination in the first place. They might find what they’re looking for within the miniature Arcadian universe that the Canadian jeweler John Hardy and his wife Cynthia have built. In addition to having founded the Green School, an alternative K-12 in the heart of the jungle that is known for its environmental focus, they oversee Bambu Indah, a hotel that they opened outside of Ubud in 2005, with a smattering of Javanese teak buildings perched atop a winding swimming pond. The latest addition to the two-and-a-half acre estate is the River Warung, an open-air, eight-table cafe designed by John and his daughter Elora Hardy, who is the founder of Ibuku, a Bali-based design firm that specializes in bamboo architecture. Here, treated bamboo slices have been bent into overlapping arches that support a curved roof of hand-folded copper shingles. ‘‘I wanted it to appear as Left: an antique though it was constructed by a highly boat outside the intelligent bird,’’ Elora says of the nestlike structure, which sits next to the Ayung River in restaurant. an emerald-hued valley of rice terraces. To get there, guests take an elevator down 60 feet bambuindah.com. and cross an irrigation canal via suspension bridge. Once seated, they can enjoy Balineseinspired dishes, including wood-fired jackfruit steak rubbed with turmeric and galangal, as well as minced fish wrapped in banana leaf and served with corn fritters and greens sautéed in coconut oil. ‘‘It’s everything we loved about the island that is now so hard to find,’’ says Cynthia. — Gisela Williams

Ties That Bind ‘‘ONLY CONNECT!’’ begins the most famous passage of E. M. Forster’s 1910 novel ‘‘Howards End,’’ which asks us to unite ‘‘the prose and the passion’’ of life, to ‘‘live in fragments no longer.’’ It also points to the book’s theme of social connection and its obstacles — a topic that has an additional charge in our era of supposed connectivity. Contrasting the principles of two privileged English families — the bohemian, open-hearted Schlegels and the staid industrialist Wilcoxes — as their lives overlap with an intellectually curious but impecunious young man, Forster’s masterpiece took on the big, divisive issues of the day — class, power, gender — while illuminating commonalities, like the need for love and sex, shelter and a sense of purpose, with moral complexity and tender comedy. Few novels feel as deserving of fresh consideration, and this spring, two worthy adaptations offer just

that. A new BBC/Starz miniseries written by Kenneth Lonergan emphasizes Forster’s deep humanism over the sumptuous Edwardian period details underlined in the beloved 1992 Merchant-Ivory film rendition. As Margaret, Hayley Atwell brings a warm heroism to one of English literature’s great women, though most significant of all is the decision to cast actors of color in supporting roles, a reminder that Britain never did resemble the one Brexiteers might have imagined. Meanwhile, a queer retelling of the story, written by Matthew Lopez, directed by Stephen Daldry and starring Vanessa Redgrave and John Benjamin Hickey, just wrapped off West End at the Young Vic. ‘‘The Inheritance’’ transposes Forster’s story to present-day New York, grounding it in the gay community a generation after the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. At a time in which it feels like the Wilcoxes have won, at least for the moment, it’s nice to believe that the Schlegels are still in charge of the story. — Megan O’Grady

MINI MARKET

Classic carryalls to go the distance.

From left: Salvatore Ferragamo bag, $2,800, (866) 337-7242. Mansur Gavriel bag, $1,295, mansurgavriel.com. The Row bag, $5,600, (212) 755-2017.

11

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: ALINA VLASOVA; MARI MAEDA AND YUJI OBOSHI (3); COURTESY OF LOUIS VUITTON MALLETIER (2)

GREEN SCREEN

DOWN IN THE VALLEY

New Hardware

PEOPLE, PLACES & THINGS

Foundrae, the fine jewelry line Beth Bugdaycay launched with her husband, Murat, in 2015, is all about the personality. Wearers can stack rings, pair enameled charms and create custom, 18-karat gold pieces that pull from the brand’s 60-strong lexicon of symbols — a triangle for transformation, a lion’s head for strength. Foundrae’s first store, opening this month in downtown Manhattan at 52 Lispenard Street, takes a similar approach: An antique roll-top jeweler’s bench (where shoppers can see items get soldered) and a suite of 1970s- era rounded leather armchairs by Giancarlo Piretti sit alongside contemporary commissioned pieces such as a moody landscape by Tyler Hays of the furniture company BDDW. As intended, the overall effect is more homey and welcoming than that of a traditional jewelry store. There are even shelves lined with books, including those by 20th-century American writer Jessamyn West, Bugdaycay’s ancestor, that visitors can borrow. ‘‘People use our pieces to tell their own stories,’’ says Bugdaycay, who has seemingly inherited an instinct for narrative. ‘‘You end up being friends with every customer.’’ foundrae.com — Kate Guadagnino From top: Foundrae necklaces and rings displayed in bronze vitrines atop custom ceramic pedestals; Bugdaycay in the sitting area of the new store.

Watch Beth Bugdaycay make something for T on tmagazine. com and @ tmagazine.

NOW BOOKING

12 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

WAVE Berbere — a deep-red spice blend whose recipe, like those for curry and mole, varies from kitchen to kitchen, but typically begins with red pepper, cardamom, fenugreek and ginger — has long been a staple in Ethiopian cooking. ‘‘It’s what lends the stewed and roasted dishes called wats their distinctive and aromatic heat,’’ says Sam Saverance, co-owner of Brooklyn’s vegan Bunna Cafe, which serves a red lentil wat (at the center of the platter pictured above) as well as kategna, a berbere and olive oil paste spread over injera (sourdough flatbread). In addition to making berbere-spiced classics, Christopher Roberson of Etete, a contemporary Ethiopian restaurant in Washington, D.C., has lately been experimenting with berbere in other types of dishes, too, as with his popular injera chicken tacos with collard greens and fresh farmer’s cheese. Now, chefs across the country are following suit, and berbere is popping up in all kinds of cuisines. At Salare, a New American restaurant in Seattle, Edouardo Jordan braises blanched octopus in a sauce with berbere, red wine and crushed tomatoes — his spin on octopus tagine. ‘‘The complexity just wakes everything up,’’ he says. Maxcel Hardy, who plans to use lots of berbere (‘‘it’s not a question of if, but how’’) at Honey, his Afro-Caribbean restaurant set to open in Detroit later this year, first encountered the ingredient growing up in Miami. Chef Ayesha Nurdjaja, meanwhile, was inspired to recreate a berbere-rubbed chicken kebab for Shuka, Vicki Freeman and Marc Meyer’s new Mediterranean place in New York, after spending a week with an all-male Bedouin tribe in the Moroccan desert. The key, says Ari Bokovza, who recently added a pan-roasted hake with a berbere-laced chickpea ragout to the menu at New York’s Claudette, is to avoid store-bought blends — his take includes caraway, turmeric and spiced paprika. ‘‘It’s not labor intensive, so why not make it your own?’’ — Katie Chang

Modern Country Ninety minutes east of Lisbon, amid the knotted olive trees and historic farmhouses of Portugal’s Alentejo region, sits the defiantly modernist Villa Extramuros. A Tetris-like assemblage of stone, glass and whitewashed concrete, the five-room bed-and-breakfast, which opened in 2012, was designed by Lisbon-based architect Jodi Fornells and eclectically decorated (Saarinen Tulip chairs, striped wool rugs from nearby Monsaraz) by its owners, François Savatier and Jean-Christophe Lalanne, a French couple. Now, they’ve teamed up with Fornells again to add a pair of free-standing cottages, just down the path (and past the infinity pool) from the main building. The facades of the new structures — perfect cubes of 500 square feet — are covered with local cork, and their interiors have been outfitted in a style Savatier calls ‘‘écologique-pop,’’ with ’70s-era brass lamps, handmade Artevida wall tiles, spindly-legged stools by Jasper Morrison and geometric prints by Aurélie Nemours. Here, after a breakfast including fresh figs and pasteis de nata delivered right to their door, guests might venture out to the nearby city of Évora, home to a 13th-century Gothic cathedral and the remnants of a Roman temple. Those returning to the compound in the evening need not worry about getting lost in the groves — each bungalow has a rectangular neon light affixed to it, one red and the other a gleaming yellow. villaextramuros .com — Gisela Williams

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: KYLE KNODELL (2); NICOLAS MATHEUS (2); ANDERS AHLGREN

HEAT

Paris to Doha Ghada Al Khater, a Qatari political ARToonist, who gained recognition and praise for her blockadeinspired art, successfully completed a threemonth residency program at the renowned Cité internationale des Arts, Paris, one of the biggest and most important art residencies in the world. Held under the patronage of Qatar Museums (QM) Chairperson, HE Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the Paris Residency is an extension of QM’s Fire Station: Artist in Residence program in Doha. To celebrate her accomplishments, Ghada hosted an exhibition at the Doha Fire Station in May. One of her most recent works, completed during the Paris residency, is “Blockade: Energy Drink”, which presents a humorous take on how the blockade motivated the country to move forward while relying on its own people. – Udayan Nag

Broadening Horizons Ahmed Al Jufairi, known for pushing the boundaries of self-expression and toying with the concept of freedom, became the fifth Qatari artist to join the Paris Art Residency Program. Al Jufairi will be joining the program in Studio Qatar at the Cite Internationale des Arts. A graduate from Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar with a major in Painting and Printmaking, Ahmed focuses on the beauty of imperfection, sending out an important message to the audience, and explaining that “beauty” and “perfection” are relative terms. Fascinated by what makes us unique, Ahmed has also been known to tackle the subject of social acceptance, arguing that uniqueness and individuality are keys to beautiful innovations. Khalifa Al Obaildy, Director of the Fire Station, said: “His (Ahmed’s) artwork combines the best of the East and West, delivering a unique interpretation of the beauty of co-existence.” – Udayan Nag Exhibits of artist Ahmed Al Jufairi.

Art in Everything

Exhibits on display in Gallery One.

Inspired by the retail stores of the world’s greatest galleries and museums, Gallery One was launched in the UAE in 2006. It has grown into an inspired network of eclectic retail spaces, driven by the one core philosophical belief, “Art in Everything”. Gallery One founder, Gregg Sedgwick, said that since its inception, the company had constantly been in search for new artistic talent. “Whether it’s an artist, painter or photographer, or a product designer with a brilliant idea, newness is the lifeblood of retail. We are therefore becoming increasingly recognised for our unique retail ranges, which exude cultural provenance, beautiful packaging and regional relevance.” Sedgwick said the company was wholly committed to applying its design philosophy as it continued to expand across other regions throughout the world, describing Gallery One as “the antithesis of the ‘elitism’ often associated with the gallery genre”. – Udayan Nag 13

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: DOHA FIRE STATION; DOHA FIRE STATION; GALLERY ONE; DOHA FIRE STATION

A woman taking photographs of Artoonist Ghada Al Khater's work.

Our Heritage is Your Heritage Keeping the spirit and traditions of Qatar very much alive, Ramadan, the holiest month in the Islamic calendar, was once again observed across the country. By Udayan Nag

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE WESTIN DOHA HOTEL & SPA.

14 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

PEOPLE, PLACES & THINGS QATAR

HERITAGE

Lavish arrangements were made during Ramadan at the Westin Doha Hotel & SPA and Sheraton Grand Doha Resort & Convention Hotel.

15

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE WESTIN DOHA HOTEL & SPA AND SHERATON GRAND DOHA RESORT & CONVENTION HOTEL.

FASTING, FEASTING, and an ambience of benevolence: it's that time of the year again for Qatar and its residents. Despite abstinence being the order of day from dawn to sunset for majority of the Muslims, there is a lot to look forward to. The shorter working hours provide respite to the residents, and once the fast is broken, it's time to feast in the form of numerous iftar and suhoor gatherings. The spirit and tradition are given a further boost in the middle of the month when children dress up in bright clothing to participate in Garangao. The royal mansion at Sheraton Grand Doha Resort & Convention Hotel was one of the major attractions during this pious month. It reflected the rich Qatari heritage with its lavish Turath Ramadan Tent set up in the Al Majlis Ballroom. Its exquisitely decked dining areas offered the ideal setting for an iftar feast as well as an intimate suhoor. Turkish Airlines also held a Ramadan suhoor event for its media partners, which took place at the Shangri-La Hotel in West Bay. The evening was led by Mehmed Zingal, General Manager of Turkish Airlines’ Qatar office. Also, as part of its ongoing commitment to the holy month of Ramadan, Marriott International celebrated the ninth annual “Iftar for Cabs” initiative at participating Marriott hotels in the Middle East, including eight hotels of the Qatar Marriott Worldwide Business Council.

People

TWO BY DESIGN

With their feet in two countries and two fields — she’s a designer, he’s a restaurateur —

Home in

Two Worlds Naina Shah and Abhishek Honawar are at the forefront of an Indian creative class.

16 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

By Alice Newell-Hanson Photographs by Flora Hanitijo

OUTSIDE NAINA SHAH and Abhishek Honawar’s Manhattan apartment, the sky is the color of raw concrete. But inside the couple’s airy East Village apartment, which smells faintly of Assam tea and glints with eye-catching Indian regional crafts — miniature caskets inlaid with mother-of-pearl, handwoven kauna grass baskets, carved wooden spirit masks collected on their travels through Rajasthan, Kerala and Goa — everything sparkles with light. Shah creates intricate decorations for European and American fashion houses using traditional Indian craftsmanship; she and her mother run the Mumbaibased bespoke embroidery company Aditiany, which produces hand-finished embellishments for

the likes of Gucci, Erdem and Alexander McQueen. Honawar, a hotelier and restaurateur, operates, among other properties, the five-bedroom hotel 28 Kothi in Jaipur — a terraced jewel box of a guesthouse owned by Siddharth Kasliwal, an heir to Jaipur’s legendary jewelry emporium the Gem Palace. In the eight years since the pair started dating, and the two since they were married in Jaipur, Honawar and Shah’s respective creative worlds have become inextricable. You have likely already seen Shah’s work, possibly without realizing it. The gold sequin snakes that wound up on the Renaissance-inspired gowns of Gucci’s cruise 2018 collection are the handiwork

of Aditiany artisans. Each iridescent sea-foam-green sequin on the shimmering Calvin Klein dress that Lupita Nyong’o wore to the 2016 Met Gala was applied, by hand, at the company’s Mumbai atelier. Shah, who grew up in New York and learned the trade by working with her mother (who founded Aditiany in 1991), helps brands realize their most otherworldly visions, overseeing a 30-person-plus team of fabric buyers and Naina Shah (left) and embroiderers in Mumbai Abhishek Honawar’s and New York. The atelier Manhattan apartment is filled with objets from has helped transform their transcontinental a mohair sweater into a existence and shared garden of silk trompe-l’oeil love of design.

Clockwise from top left: Shah sifting through her voluminous stock of embroidered fabrics at her showroom in New York; Hindu deities in Shah’s office; a Swarovski-crystal snake that adorned a 2012 Ralph Lauren dress; Shah’s stash of fine ribbons and appliqués; the dining table in the couple’s East Village apartment doubles as Honawar’s desk.

roses (Dolce & Gabbana), hand-beaded an entire custom jumpsuit tailored to model Bella Hadid’s body (Alexander Wang) and turned a velvet Saint Laurent smoking jacket into a galaxy of embroidered stars for Keith Richards. Producing each design requires its own kind of sleight of hand. The 33-year-old Shah splits her time between her studio in Mumbai and New York, where Aditiany has a showroom in the garment district, a storehouse filled with thousands of embroidery swatches: There are yards of gold bullion fringe and Chantilly lace, a rainbow of Murano glass beads and a vast library of brilliant crystals and semiprecious stones. She also makes about four trips a year to Europe to discuss upcoming collections with various houses. The creative process is collaborative: Design teams relay their references for the upcoming season, and Shah then presents samples of embellished fabrics — ’20sstyle bead-trimmed lace, fragile Tyrolean-esque flower-stitched silk tulle and new embellishment techniques being developed by the studio in Mumbai, such as embroidery using recycled materials — that might fulfill those imaginings. Recently, Honawar began accompanying Shah on her visits to London, Paris and Milan, and joining

her at meetings. ‘‘At first, people thought it was bizarre for me to meet [with] all these houses,’’ he says. ‘‘But I thought it was so interesting to sit there with someone like the head of Gucci or Prada as they tell you what they’re going to do for the next few seasons.’’ Maintaining a blurred boundary between personal and professional life could make some couples feel claustrophobic, but for Shah, Honawar’s interest is both creatively fulfilling and fun. Building relationships with luxury brands has given the 34-year-old Honawar ideas for new businesses as well, including a forthcoming design studio, a collaboration with his wife that Shah says will offer ‘‘everything from linens to glassware to the perfect towel,’’ and will highlight the best of Indian artisanal traditions. Like Shah, Honawar, who was raised in Mumbai, works mainly between India and New York. In addition to co-founding 28 Kothi in Jaipur, the threeoutlet gastropub the Woodside Inn and the Pantry, a bakery in Mumbai, he also co-founded Inday, a vegetable-heavy cafe in N.Y.C.’s NoMad district. Along with two new projects in Mumbai — the recently opened Bombay Vintage, a traditional Indian restaurant, and a still unnamed Southeast Asian restaurant and cocktail bar — he’s also developing

a Puglian-influenced auberge on 60 acres in the Rajasthani countryside. For years, he says, major Indian cities simply didn’t have the kind of dining options you’d find in Paris or London: You ate meals at home, not outside of it. The past decade, however, has changed that: American-born Indians, like his wife, have returned to their parents’ homeland, bringing with them expectations of a truly global restaurant scene. But for all Honawar’s contributions to that scene, 28 Kothi, which he designed in 2016 as a respite for the myriad fashion designers, jewelers and photographers who travel through Jaipur, remains one of his favorite projects. The guesthouse’s new cafe will serve elevated vegetarian regional classics such as the traditional rice dish biryani — which he’s reimagined with spiced quinoa, crisped okra and a sharp-sweet tomato chutney — or paneer, a firm farmer’s cheese he’s converted into cottagecheese form and mixed with sprouts grown in the kitchen’s garden. Next, he wants to create a larger hotel ‘‘that exhibits the true India’’ to the wider world. ‘‘It’s a vast country with diverse culture and history,’’ he says. ‘‘My idea of modern Indian luxury is preserving that heritage while presenting it to travelers in a language they understand.’’ 17

PEOPLE QATAR

THE ARTIST

Clockwise from top left: A selection of the pieces from the capsule collection; the make-up bag designed by Fatma Al Mulla incorporates her signature colorful illustrations.

Pop Culture Creative We first met Fatma Al Mulla some four years ago when she had just discovered how powerful the internet was in making careers.

THE POWER of viral sharing had turned her illustrating hobby into a flourishing merchandising venture featuring her creative prints. The Emirati design talent Fatma Al Mulla began documenting cult obsessions among communities in the Gulf and immortalised them in illustrations. “I started creating illustrations of these items that included short comments with the objects. These comments were all in Arabic and in a play of words they represented two different meanings, depending on how you would like to interpret them,” she explains. Young people across the region identified with these symbols of luxury and embraced the quirky designs by Al Mulla that allowed them to express their interests. “A girl told me that she used the Cartier bracelet illustration as her display picture, and her fiancé actually took the hint

and bought her one shortly after,” Al Mulla said. The power of social sharing is what Al Mulla most admires. The domino effect of one sharer to another has catapulted her fame. When the requests started pouring in to purchase Al Mulla’s illustrations, she decided to put them on T-shirts and make the experience physical, beyond the internet. “Art is meant to be shared and I always feel it is not for me to put my name on it but when I started to make these t-shirts, fans found my blog and discovered that it was me.” The brand FMM by Al Mulla was born. She describes it as a pop-culture design line, made with love in Dubai and inspired by the society we live in. The brand has since expanded to include dresses, accessories, bags, and leather goods while Al Mulla’s creative work has earned her various regional accolades.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF TOMMY HILFIGER

18 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

By Debrina Aliyah

This season, the Emirati artist has partnered with Tommy Hilfiger to design a make-up bag that is now available in select regional stores of the brand. A collaborative effort that coincides with Tommy Hilfiger’s Ramadan collection, Al Mulla merged the collection’s floral pattern with her own interpretation on the bag’s design. “I wanted to celebrate the floral pattern in my own way. It was very important that the brand had allowed me the creative freedom. I’ve always incorporated floral patterns in my past designs, so this collaboration just felt right,” explains the young artist who is also the ambassador for this season’s Ramadan collection. Featuring styles for young girls, new-borns and women, the capsule is the brand’s fifth initiative for Ramadan. “As an Arab Muslim woman, I feel very proud for such a major brand to focus on Ramadan and the significance of the holy month. This initiative through fashion feels special to me,” Al Mulla says. The collection includes two gowns for women combining deep navy tones with silk chiffon fabrics and floral details, six dresses for girls in floral prints and stripes, and rompers and dresses with bow details for newborns. “I would wear the collection with statement accessories and jewelry, and perhaps even colorful shoes.”

19

Clockwise from top: The Emirati designer has won regional accolades for her creative work; the Ramadan capsule is available in select regional stores.

20 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

Places

OBJECTS

Free Forms

Wired, webbed or sculptural — the latest outdoor furniture seems to defy gravity. Photographs by Leandro Farina Styled by Theresa Rivera

Clockwise from left: Alwy Visschedyk for Summit X506 slipper chair, $3,730, summitfurniture.com. Stefano Giovannoni and Elisa Gargan for Vondom Stone lounge chair, $835, vondom.com. Chilewich Basketweave cube, $295, chilewich.com. Rodolfo Dordoni for Minotti Caulfield coffee table, $2,730, minottiddc.com.

21

Clockwise from top: Lionel Doyen for Manutti San sofa, $5,278, walterswicker.com. Marc Thorpe for Moroso Husk armchair, $630, morosousa.com. Lorenza Bozzoli for Dedon Brixx side table, $1,680, dedon.de.

OBJECTS

DIGITAL TECH: ISAAC ROSENTHAL. SET ASSISTANTS: LUKAS ADLER, EDDIE BALLARD AND HOLLY TROTTA

PLACES 22 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

Clockwise from top left: Paola Navone for Baxter Manila armchair, $9,520, ddcnyc.com. Russell Woodard for Woodard Furniture Sculptura bench, $1,150, dwr.com. SheltonMindel for Sutherland Continuous Line lounge chair, price on request, sutherlandfurniture.com.

WANDERLUST

Far From the Raging Surf

Clockwise from top left: the view from Kula Lodge, with Maalaea Bay in the distance; a bedroom at Paia Inn; a lemon grove at O’o Farm.

High above Maui’s famed beaches, in the island’s fertile bohemian heartland, the hills are piney, the air is scented with lavender and cowboys still wander past on horseback. By John Wogan Photographs by Joe Leavenworth

STAY Lumeria Maui The first thing one notices at this wellness retreat in Makawao is the silence. Shrouded with bamboo and palms and enclosed by a lava rock wall, it has 24 guest rooms with colorful Indian cotton textiles covering the pillows and daybeds, and hosts yoga and meditation classes on the grassy lawn. Breakfast includes papaya, mango and guava straight from the trees. Other meals are had at the hotel restaurant, which serves healthy-leaning dishes like freshcaught mahi-mahi with heirloom tomatoes, and house-made ulu (Hawaiian breadfruit) with a sweet persimmon chutney. lumeriamaui.com. Kula Lodge Built into the northern slopes of Haleakala Crater just outside of Makawao, Kula Lodge is as much a time capsule as a hotel — it opened in 1951 and is known for

its rustic, kitschy charm (rocking chairs and floral bedspreads). The property’s five shingled-wood cottages, each with its own fireplace and balcony, offer sweeping views of the neighboring islands. There are no televisions (or air conditioners, though they’re hardly needed 3,200 feet above sea level), and so guests spend time reading under blooming jacaranda trees in the garden and lingering over bowls of macadamia-nut pesto pasta in the glass-enclosed lodge restaurant, also famous for its sunset cocktail hour. kulalodge.com. Paia Inn With the island’s best organic food market, Mana, and half a dozen contemporary art galleries, the town of Paia — about five miles northwest of Makawao — offers the same rural-bohemian spirit as Upcountry, but with beach access as well. The five-bedroom Paia Inn

23

A VERDANT EXPANSE of misty hills punctuated with tiny, preserved-in-amber towns, Central Maui goes largely ignored by sunbathers and surfers congregating on the island’s southern towns of Wailea, Lahaina and Kapalua. Sitting as high as 3,600 feet, Upcountry, as this 200-square-mile area by Haleakala Volcano is called, has cooler temperatures (at night it can approach freezing) and more eucalyptus trees than coconut palms. It became an agricultural center in the late 1700s, when a British naval captain gave Hawaii’s King Kamehameha I a herd of longhorn cattle that spawned an entire ranching industry. There aren’t as many paniolos (Hawaiian cowboys) today as there were in the 19th century, but several big ranches remain, as does a general appreciation for living off the land: In addition to the ranches, there are coffee farms, lavender fields and scenic hiking loops through forest reserves. Many of Upcountry’s 38,000 residents (less than one-fourth of Maui’s overall population) live in and around its small, historic towns, which include Haiku, Pukalani and Makawao, former pineapple plantations and ranch communities established in the 1800s. As industrialization forced plantation owners to downsize post-World War II, the families of the primarily Hawaiian, Chinese, Portuguese and Japanese workers who remained were joined in the 1960s and ’70s by a wave of mainland hippies looking to get off the grid. (Willie Nelson and Mick Fleetwood have homes nearby.) Over the past decade or so, the area’s relatively cheap housing and temperate climate have attracted all sorts of wanderers, dropouts and seekers, including jewelry makers, woodworkers and glassblowers, as well as a new generation of farmers growing organic produce (poha berries, lilikoi) for local restaurants. (The cuisine here leans more toward Provençal than taco truck.) And so, these days, Upcountry is worth more than just a drive-through on the way to the rocky, rust-colored terrain of the island’s most spectacular national attraction: Haleakala Crater, 10,023 feet above sea level and best experienced at sunrise, when the ghostly fog lifts to reveal peaks and valleys all around. You may even realize you don’t need a beach after all.

WANDERLUST PLACES

opened there in 2008 in a two-story, bougainvillea-fringed 1920s-era stucco building. Its simple décor of hand-carved koa wood daybeds and bright white linens is offset by local painter Avi Kiriaty’s vibrant depictions of ancient Polynesian life. There’s also a spa offering volcanic stone and coconut oil massages, and a cafe that’s become a magnet for surfers, who stop in for a juice — try the Shrub Sparkler, made with watermelon and hibiscus — before hitting nearby Baldwin Beach. paiainn.com.

Clockwise from top left: the ’50s-era Kula Lodge; a volcanic stone wall at Ulupalakua Vineyards; coconut cake at Kula Bistro; Maui Gold pineapples on their way to becoming wine at Ulupalakua Vineyards; a table at Lumeria Maui’s restaurant, the Wooden Crate.

24 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

EAT O’o Farm Crops at this eight-acre establishment in Kula range from coffee and kaffir limes to mint and marigolds. Founded in 2000 by two surfer friends, O’o supplies both the Maui Food Bank and local purveyors, including the farm’s openair restaurant, Pacific’O, located on the western part of the island. There, you can find vegetablefocused dishes like roasted Maui onion and beet confit with hijiki, but in Upcountry, you can simply go to the source: Twice-daily tours through the orchards conclude with a family-style meal of ahi tuna marinated in lemongrass oil, roasted rosemary chicken and heaping platters of grilled fennel, chard and eggplant. oofarm.com. Makawao Steak House This green-shingled, 1927-built structure, which sits on Makawao’s sleepy downtown strip of Baldwin Avenue alongside hippie shops peddling crystals and wind chimes, houses what may be Upcountry’s most old-school restaurant. Its clubby wood-paneled dining room has studded leather armchairs and oil paintings, and in the adjoining

fireplace-lit cocktail lounge, mai tais are served without a hint of irony. The food is predictable — truffle fries; perfectly marbled grass-fed ribeye from nearby Hoku Nui Farm — but deeply satisfying after a day spent hiking Haleakala. makawaosteakhouse.com.

plus traditional island specialties, including one of the best takes on loco moco — a gravy-smothered hamburger patty with two over-easy eggs, sautéed mushrooms and onions all served over steamed white rice. kulabistro.com. SHOP

Kula Bistro A low-slung roadside cafe 14 miles up Kula Highway from Paia, Kula Bistro is an anomaly in a place where many businesses are run by descendants of the original owner. But ever since Italian Luciano Zanon opened his cheerful, fastpaced restaurant with his Maui-born wife, Chantal, in 2012, it’s been a hit. Zanon makes Italian staples with a Hawaiian twist, such as woodfired pizza topped with kalua pork and chunks of fresh pineapple,

Hot Island Glass Founded in 1992, this Makawao gallery took off nearly a decade later when two of Hawaii’s leading glassblowers, collaborators Chris Richards and Chris Lowry, purchased it from the previous owner. They’ve since filled the wooden plantation-style building with their own work — swirling cerulean and scarlet vases and sculptural pieces with multicolored jellyfish forms that appear to hang in midair — as

well as a few items from other makers, including Jim Graper’s sea-urchin-like paperweights. hotislandglass.com. SEE Ulupalakua Vineyards Upcountry’s nutrient-dense volcanic soil accounts for Maui’s only vineyard, which stretches across Haleakala’s southern slopes and grows everything from malbec and syrah to chenin blanc and grenache. Tasting tours start at King’s Cottage, a stone dwelling built as a guest house for King David Kalakaua, Hawaii’s last reigning royal. Wine, though, is just one aspect of the 18,000-acre ranch, which also offers horseback riding through lush pastures and woodsy areas dense with eucalyptus, jacaranda and camphor trees. mauiwine.com.

WAYFARING

Let's Go For A Walk The UK’s largest UNESCO World Heritage Site sprawls over an impressive 229,200 hectares and is emblematic of one the nation’s favorite past times, walking. By Debrina Aliyah

WITH A LANDSCAPE OF MOUNTAINS and ranges that never seem to end and lakes of sparkling blue waters, it is easy to see how the Lake District National Park has for years become a source of cultural and artistic inspiration. But while literary greats including William Wordsworth and Beatrix Potter gave the region its creative association, it is the millions who visit the various peaks and mountains each year that truly gives life to the place. Walking is the simplest of actvities. Be it around the lakes, through the villages, up the mountains or across the ranges, the national park has endless options that is suitable for any level of fitness. But of course, the geography is equally as exciting for lake cruises and kayaking as well as intense biking and swimming. To just simply absorb the natural magnificence of the landscape, we recommend easy walks and cultural explorations of the little villages. Soak in the sun during the warmer months and enjoy a generous serving of ice cream from English Lakes, the producer of locally churned goodies from the area’s cows. And if you feel like it, try your hand at being a farmer for the day by tending to the livestock.

Clockwise from top: The Bridge House a 17th century home that is still intact in Ambleside; a walk in the woods of Rannerdale Knotts in Buttermere.

Woodhouse Buttermere A cosy little bed and breakfast right on one of the smaller lakes, Crummock Water, serving as a great base to explore the surrounding areas. Family-run with intimate service and homely facilities, the rooms are charmingly appointed with really comfortable beds that we are still dreaming of. Dinner service is by request and remember to save room for the excellent desserts. Mountaineering guide services are available. www.woodhousebuttermere.uk Basecamp Tipi Luxury camping accommodation in a secluded corner of the National Trust Campsite with gorgeous views of Bowfell and Langdale Pikes. Each

tipi is structured on a wooden platform and comes with a stove, sheep skins, lanterns, fairy lights and logs. Designed as a gathering space, the tents are meant to sleep up to four and all you need to bring are sleeping bags and a sense of adventure. www.basecamptipi.co.uk Brimstone at Langdale A stylish luxury getaway reminiscent of a ski chalet complete with a personal assistant service to help with any requests. Perfect for couples or small groups of adults, the property has a recently opened spa to work away the aches from day-long walking and exploration. Relax on the spacious balconies with views of the never-ending mountains. www.brimstonehotel.co.uk 25

PHOTO COURTESY OF TWENTY30FORTY

STAY

26 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

PLACES QATAR

WAYFARING

EAT Kirkstile Inn Buttermere A favorite with the locals for both its hearty yet modern take on British pub food. The classic steak pie comes in the form of layered pastry sheets with meat filling a la the Italian lasagna while the pea soup is served with delicious focaccia-inspired rolls. The sticky date pudding is an absolute must-try and the homemade custard deserves an encore. www.kirkstile.com Great North Pie This cozy little store in Ambleside is

home to some of the best pies in the UK. Winner of multiple awards at the 2015 British Pie Awards, chef Neil Broomfield creates unique recipes every season so there is never a fixed menu. For spring summer 2018, the Swaledale beef mince and onion pie is a must-try with an interesting cinnamon twist while the spinach and cheese pie with nutmeg works for non-meat eaters. www.greatnorthpie.co Sharrow Bay A Lake District institution with a long history and a panoramic view over Ullswater, the restaurant has a one-star Michelin rating for its

exceptional use of local produce and an impressive cellar. Menus are served for both lunches and dinners but be sure to try its Sunday lunches offering a taste of British tradition. www.sharrowbay.co.uk EXPLORE Scafell Pike The main highlight for most visiting the Lake District is the magnificent walk to the top of the UK’s highest peak. With a total ascent of 1,012 meters arriving at the highest point at 978 meters, it takes an average hiker about eight hours to complete. It is a great full-day walk and aboveaverage level of fitness is required to complete the hike but, with the right guide and proper equipment, most can finish it. www.scafellpike.org.uk Hill Top House With the arrival of the animated movie Peter Rabbit in cinemas this year, it is no surprise that the frenzy for the beloved cartoon character has picked up again. Hill Top House, a stone’s throw away from Hawkshead, is the

PHOTO COURTESY OF TWENTY30FORTY

Right: The common space at the charming family-run Woodhouse bed and breakfast; left and opposite: the various mountains and ranges across the region offer walking options for those with different fitness levels.

27

WAYFARING

Castlerigg Stone Circle For some pre-historic marvels, head on to Castlerigg Stone Circle, one of the most atmospheric and dramatic British stone circle sites in the region. With a backdrop that looks like something straight out of a Tolkien fantasy book, these 5,000-year-old stones overlook the Thirlmere Valley. The purpose and construction of the stone circle are

shrouded in mystery as archaeologists have yet to figure out its actual origins but it is widely considered to be a Neolithic period meeting place. www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/ places/castlerigg-stone-circle.

The local church right around the corner from Crummock Water.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TWENTY30FORTY

28 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

PLACES QATAR

farmhouse where Peter Rabbit’s creator Beatrix Potter lived. The late English writer and illustrator had based the character’s kitchen garden on this property, the green patch a big attraction with adult and young fans alike till this day. Entry is by timed ticket and reservations are recommended. www.nationaltrust.org.uk/hill-top

Things

FOOD MATTERS

Clockwise from top left: Supermoon pistachio-rose croissant; Supermoon mango croissant; Vive la Tarte blood orange croissant; Dominique Ansel pear-chamomile cronut; Vive la Tarte orange-blossom-za’atar croissant; Sugarbloom white-miso kouign-amann; Chanson pistachio éclair; Supermoon strawberrylychee croissant; Chanson lemon-poppyseed kouignamann; Dominique Ansel brown-sugar kouignamann; Chanson pistachio croissant; Bake Code charcoal-matcha croissant. Next page, top left: Vive la Tarte strawberry shortcake croissant.

For years, no chef dared try to improve the croissant. Now, though, a new generation of bakers is reinventing the most iconic of French patisserie.

Le Sacrilège!

THE CROISSANTS OF Baker Doe — a delivery-only pastry service in San Francisco, run by a husband and wife who decline to reveal their identities — appear like a new species startled in the wild. One is striped blue, with a coif of cotton candy in hydrangea hues and a lode of chile-enflamed orange curd waiting to be unleashed; another, ringed in deep purple, flaunts a lavender shard of ube (purple yam) like a lone, useless wing. They are originals, yet they don’t exist

in isolation: Others of their kin — that is, pastries in thrillingly deviant forms with classical French lineage but non-canonical ingredients (often drawn from Asian cuisines), as likely to be savory as sweet — can be spotted at Sugarbloom Bakery in Los Angeles, confettied in nori; at Bake Code in Toronto, blackened by charcoal under a rosy crust of mentaiko (cod roe); and at Supermoon Bakehouse in New York, piped with rum crème

pâtissière and pineapple jelly in a mirage of a piña colada. Is this blasphemy or natural evolution? It’s not the first time pastries have undergone mutations in recent history. Nearly five years ago, the French-trained pastry chef Dominique Ansel trademarked the cronut, that cannily named croissant-doughnut hybrid sold from his storefront in SoHo, New York. Hoards lined up before dawn for limited-batch runs that vanished within the hour, to be resold

on the black market by scalpers at a 1,900-percent markup (as much as $100 each). The cronut was fetishized, then scorned for being fetishized, then imperfectly and ubiquitously reproduced. Dunkin’ Donuts sold millions (of a version that a corporate spokesman insisted had been in development for decades). Within a year, the oracular science-fiction writer William Gibson had published a novel forecasting a future in which cronuts were churned out by 3-D printers.

29

By Ligaya Mishan Photographs by Patricia Heal Styled by Beverley Hyde

cake.’’ Carême has disciples in Paris today, including Christophe Adam, known for éclairs ornamented with edible silver, popcorn and Mona Lisa eyes; Jonathan Blot, conjurer of macarons that taste like bubblegum; and, of course, Pierre Hermé, who daubs raspberry-lychee pâté inside croissants and showers them with candied rose petals. Like the original viennoiserie, which were painstakingly elegant pastries designed for the Hapsburg court in imperial Vienna that eventually became indispensable to the city’s sidewalks, their decadence is matched by the virtuosity of their construction and their element of surprise: They are, then as now, as much for beholding as for eating. Their contemporary allure is aided by the diminishment of desserts at midrange restaurants, which after the recession of 2008 began to shed pastry chefs, unable to justify the expense for a course that yields little profit. As restaurant desserts have become simpler and homier — oliveoil cake, anything with chocolate — once plainspoken baked goods have turned rococo, offering an aura of luxury, enhanced by how difficult they are to procure before selling out each morning. At $4 to $8 each, these small but elaborate edifices seem worthier than the run-of-the-mill pastries available at every urban corner deli The decadence of these pastries and curbside coffee cart, enabling is matched by the virtuosity of their their artisans to cover the everconstruction and their element increasing cost of basic ingredients, of surprise: They are as much for particularly butter, whose price hit a historic high last year. beholding as for eating. Indeed, French butter, which has a higher percentage of fat and a pronounced tang from cultured cream, it’s the croissant that’s seen as desserts, have remained static over time: is so desirable across the globe, it’s being in danger of degradation: the starting to disappear from grocery Blancmange, a molded milk pudding, noble, labor-intensive French shelves in France. This is partly was once a chicken casserole; craggy pastry sullied by its union with the coconut Italian-Jewish macaroons share because more people are making crude, arriviste American doughnut pastries than ever before; as a French ancestry (going back to early Sicilian or muffin. (Another iteration was professor explained to The Economist pasta) with the polished round French unveiled in January by Vive la Tarte in November, ‘‘China has discovered macarons that have ruffled hems, in San Francisco: the tacro, a savory croissants.’’ But if the trend continues, which languished as solitary disks until pork- or chicken-stuffed taco with the croissant as we know it — a someone sandwiched them around a croissant shell.) straightforward compact of butter, ganache a little over a century ago. If anything, today’s nouvelle pastries flour, milk, sugar, yeast and salt — may mark a return to the spirit championed be no more. And in its place? These YET THE CROISSANT itself was born overgrown crescents too big to fit by Marie-Antoine Carême, the early of crossed borders. The butter-laden in the palm of the hand, spangled and 19th-century forefather of French layered dough has roots in medieval cooking, inventor of the soufflé and the swagged, glutted with fillings, arrayed Arab practice, and the pastry’s shape like objets d’art in austere concretecroquembouche and architect of comes from the Viennese kipferl, monumental confectionery centerpieces walled patisseries where the bakers said to have been modeled after the fuss like apothecaries. They’re absurd that rose up to three feet — nearly as Islamic crescent borne on the banners until you try them: salty and sweet high as the sculptured hairstyles of his of 17th-century Ottoman invaders. and shattering everywhere, leaving late namesake, Marie Antoinette, the (Although this back story is likely behind smears of cream and telltale Austrian princess whose own love for apocryphal, in 2013 a rebel stronghold butter fingerprints. The croissant is viennoiserie may have inspired the in Syria banned croissants as symbols dead; long live the croissant. myth of her declaring, ‘‘Let them eat of colonialism.) Few dishes, let alone

RETROUCHING: ANONYMOUS RETOUCH; PHOTOGRAPHER ASSISTANTS: KARL LEITZ, CALEB ANDRIELLA; ASSISTANT STYLIST: JESSE HASKO

FOOD MATTERS THINGS 30 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

And still people line up for Ansel’s cronuts today, at his outposts in Tokyo, London and Los Angeles, where seasonal flavors like pineapplechocolate-basil and eggnog-caramel are introduced monthly, for we are not yet immune to the novelty of pastry portmanteaus. The cruffin, made of croissant dough fastidiously draped in muffin tins to achieve a bouffant’s rise, was invented the same year as the cronut by the pastry chef Kate Reid of Lune Croissanterie in Melbourne, Australia. When another Melbourne native, Ry Stephen (currently of New York’s Supermoon), started making the puffy hybrids at San Francisco’s Mr. Holmes Bakehouse in 2014, his curd-filled cruffins proved so popular that a burglar broke in one night and ignored the cash register and equipment, grabbing only a binder of recipes. Like the cronut, these latter-day pastries — rustic kouign-amanns at Sugarbloom laminated with white miso; éclairs at patisserie Chanson entombed under Day-Glo plaques of painted chocolate — draw skepticism in part because they’re so swiftly and widely worshipped. In a culture beholden to images, it’s easy to simultaneously embrace and dismiss them as idle provocations. But for all the black garlic in the dough, the kimchi-spiked filling, the blood orange slices mashed on top, they are still viennoiserie, made in accordance with French tradition, precisionengineered with high-grade butter. (Stephen, for instance, is faithful to the revered Beurre d’Isigny, imported from Normandy.) In the croissants and their variations, the layers are as distinct as ribs, from slabs of cold butter immured in fold after fold of dough; the interior resembles a honeycomb of air, due to steam released during baking as the butter slowly melts. Some mock these as ‘‘Frankenpastries,’’ a term with echoes of ‘‘Frankenfood,’’ coined in 1992 by an English professor at Boston College expressing dismay over genetically engineered crops. That label is tongue-in-cheek, though just as Mary Shelley’s fevered novel hints at societal fears of miscegenation and ‘‘impurity,’’ the notion that these baked goods represent unholy unions suggests that there are clear borders in the culinary world that one ought not cross. Two centuries ago, the French led a shift from free-form cooking to codified techniques and built a system for achieving and recognizing mastery that still defines the professional kitchen, pastry or otherwise. So inevitably

Embellished Sandals

The laid-back staple makes a statement when bejeweled, tasseled or splashed in Pop Art color.

Photographs by Mari Maeda and Yuji Oboshi

Clockwise from top left: Missoni, $1,230. Suecomma Bonnie, $400. Miu Miu, $690. Tod’s, $995. Marni, $990. Dorothee Schumacher, $480. Prada, price on request. Marc Jacobs, $395. Carven, $850.

31

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: MISSONI SANDALS, SIMILAR STYLES MISSONI.COM. SUECOMMA BONNIE SANDALS, SHOPBOP.COM. MIU MIU SANDALS, MIUMIU.COM. TOD’S SANDALS, TODS.COM. MARNI SANDALS, (212) 343-3912. DOROTHEE SCHUMACHER SANDALS, DOROTHEE-SCHUMACHER.COM. PRADA SANDALS, (212) 334-8888. MARC JACOBS SANDALS, MARCJACOBS.COM. CARVEN SANDALS, CARVEN.COM

MARKET REPORT

OBJECTS

Bold Bedfellows

Large but surprisingly spare statement watches.

32 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

THINGS

Photographs by Anthony Cotsifas Styled by Haidee Findlay-Levin

Left: Cartier Santos de Cartier, $37,000, cartier.com. Right: Cartier Tank Louis Cartier, $27,000.

33

Bulgari Octo Roma, $13,900, bulgari.com.

34 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

PHOTO ASSISTANTS: KARL LEITZ AND CALEB ANDRIELLA. SET ASSISTANTS: RAYMOND YOOK AND DAN MONDRAGON

Bell & Ross BR03-92 Horoblack, $3,400, bellross.com.

THINGS

OBJECTS

APPAREL

A Mischievous Stitch A self-professed off-kilter artist of an unconventional medium teams up with Weekend Max Mara to bring some jazz to formal daywear. By Debrina Aliyah

of Embroidery in South Korea and, most recently, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Toile de Jouy Museum in Josas, France. “I wanted to embroider Maori face tattoos onto 18th-century figures, but there are very few toile prints available to accomplish this effectively, so I adjusted the concept and things just took off from there,” he explains. After attending the University of the Arts in Philadelphia to study surface design, he devoted his studies to the great books of Western civilization at St John's College in Santa Fe and received a BA as a math and philosophy major. After a brief stint working as an art director on Madison Avenue, he started a small design firm cheekily named Historically Inaccurate Decorative Arts, where he centered his design interests.Adopting an organic approach to his creative

Below: Saja calls his work “interferences”.

35

PHOTO COURTESY OF GEORGIA KOKOLIS

GIVE RICHARD SAJA a piece of toile de jouy and he will probably return it with a little zestful addition to put a smile on your face. If anything, the artist has in recent years helped put the spotlight back on this traditional French fabric style that at one point was mostly relegated to the realms of tapestry and homeware. But in the hands of Saja, idyllic countryside scenes get a colorful embroidery uplift to reflect a modern notion, sometimes even a little devilish but at most times just a mischievous twist. He calls them “interferences”, these embroidered additions to the original prints on the toiles. And these interpretations have won him international attention, having been exhibited in hometown New York, Paris, London, Berlin, the National Museum

APPAREL THINGS QATAR

work, Saja embraces spontaneity in deciding how the embroidery will tell a new story on the original toile print. “At best, there’s a theme. And colors are chosen beforehand but everything else is spontaneous,” he says. Perhaps it was this off-the-cuff spirit that caught the eye of Weekend Max Mara’s creative team that has been flying the flag of experimentation and collaboration in recent seasons. The brand’s Signature Collection is a collaborative effort with artists as an opportunity to test new printing techniques and materials, and to encourage new design perspectives. That, and the fact that toile de jouy is a fabric that gels with the spirit of the brand in both its tradition and its irony. For this Trophy Day collaboration, Saja’s embroidery techniques embellish silk and cotton toile de jouy textiles in a collection designed for the annual Royal Ascot races. Mirroring the artist’s offbeat interpretations on traditional prints, the collection brings a colorful and unexpected aesthetics to the rigid formal daywear rules of the races. “I attend the Kentucky Derby in Louisville annually and I channelled some of those memories into the embroidery, adorning the figures in bright and festive party attire,” says Saja. Rigorously adhering to Royal Ascot’s dress code,

ABOVE: PHOTO COURTESY OF WEEKEND BY MAX MARA; BELOW: CARLA GULER

36 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

Above: Sketches from the Trophy Day collection; below: Actress Margaret Clunie in the collection campaign.

Clockwise from top: Up-close look of Saja’s embroidery on the pieces; separates designed to adhere to Ascot Race’s dress codes.

shirt. The artist’s embroideries also extend into a small selection of shoes and bags that make the perfect accoutrement to a traditional top-to-toe race day outfit. “All the pieces of this capsule have been produced precisely with these rules in mind. The mix and match allows you to be dressed adequately for this particular event and yet maintain the everyday freshness of our brand’s DNA,” the brand’s design team says. Saja envisions a woman of both style and humor to carry off the irony of the pieces. “An evolved and intelligent woman who embraces patterns and textures,” he adds. This muse comes in the form of English actress Margaret Clunie, who plays the

Duchess of Sutherland in TV series Victoria. The unconventional beauty will be attending the muchcelebrated Royal Enclosure during the Ascot Races this month in pieces from the collection.

37

PHOTO COURTESY OF WEEKEND BY MAX MARA

the pieces are rendered in a unique colorway where embroideries are positioned differently from one another. His irreverent takes on the classic textile focus on the embellishing of 17th century-style horses and riders. “I tried to capture the essence of a holiday - fun and frivolity rippling through the prints and textures in the embroidery,” explains Saja. The ten-piece collection features a color palette of dark to light blue hues, ivory to white, and orange. Key pieces include a thigh-length overcoat of silk organdie, a cotton piquet blouse with voluminous sleeve detailing, cropped cotton trousers with a slight kick-flare and a cotton poplin

THINGS QATAR

MARKET REPORT

Candy Pastels

Pleasant soft shades to match sun-kissed summer skin.

Clockwise from top left: Calice sleeveless feather gown, QR31,600, Vivetta. Tri-color kaftan, QR3,100, Dima Ayad. Lena pintuck twill tunic, QR2,708, Zero + Maria Cornejo. Silk-blend twisted dress, QR2,400, Lemaire. Tie-front cotton-jersey t-shirt, QR780, Cédric Charlier. Harem pants with side stripes, QR3,220, Marc Jacobs. Wool crepe feather jacket, QR4,980, Christopher Kane.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: VIVETTA, DIMA AYAD, ZERO + MARIA CORNEJO, LEMAIRE, CÉDRIC CHARLIER, MARC JACOBS, CHRISTOPHER KANE.

38 T QATAR: THE NEW YORK TIMES STYLE MAGAZINE

By Debrina Aliyah

May - June 2018 162 Furniture as One-of-a-Kind Art 168 Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s Interior Worlds 174 Gotland’s Modernist Revolution

39

JASON LARKIN

Paper flowers and a vase sit on a table in the study of Chaimowicz’s new flat in Vauxhall.

A Chair (Not Made) for Sitting Artists have long been interested in the domestic space, but as the distinction between art and design becomes ever more blurred, more artists are making objects that function, and more designers are making sculpture.

40

Plus: Five designers create original furniture, exclusively for T.

By Nikil Saval Photographs by Anthony Cotsifas Set Design by Jill Nicholls

WHEN WE TALK about artists making furniture, an old debate over whether design counts as art (and vice versa) rises once again to the surface, like a shark baited with chum. Furniture designers aren’t, by the logic of the category, really artists, and artists, by that same logic, must normally be engaged in a higher pursuit than furniture. Only on occasion — thanks to a creative block, a desire to make (more) money, or a temporary absence of mind — do artists descend from the empyrean to sanctify the grimy world of designer-makers. Furniture, lovely though it sometimes may be, is functional and commercial; art is timeless and to be contemplated. That few artists or designers today would accept the terms of this debate is in part because of the 1970s and ’80s rise of postmodernism in both art and design. Postmodernists made an infamous show of confusing distinctions, and the idea that an artist’s work could also include chairs and tables became commonplace. But this doesn’t imply that the essence of both art and design has been entirely subverted. In 1994, the Austrian sculptor Franz West placed couches on the roof of the Dia Center for the Arts. The institution presented this act as an installation, and West also felt the need to justify this type of work in art-theoretical discourse, generating a Latinate category for his practice — ‘‘active reception’’ — that instantly made problematic the thing he was supposedly trying to bring about: the unity of art and design. Donald Judd, the most famous artist-turnedfurniture designer, first tried to make furniture in the mid-’60s by attempting to turn one of his rectangular volumes into a coffee table. It was a bad table, he concluded, and he threw it away, as he recalled in his 1993 essay ‘‘It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp,’’ in which he writes, ‘‘If a chair or a building is not functional, if it appears to be only art, it is ridiculous.’’ AND YET, THESE generic boundaries have been collapsing for decades. We now seem to have reached the inevitable conclusion that form and function are increasingly indistinguishable. More and more artists produce functional commercial objects — whether it’s Sterling Ruby making working stoves (even if the ones cast in bronze look like imposing sculptures) or Robert Gober making wallpaper (even if that wallpaper was on view in the artist’s 2014 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art) — and more and more designers are creating furniture that merely skirts the border of function. Rick Owens, a fashion designer who first ventured into home goods in 2007, makes plenty of usable chairs and tables, but he also makes the occasional plywood daybed that one wouldn’t dare recline on; his work is sometimes more of an aesthetic exercise, and it can look more like a geometrical study by minimalist sculptor Robert Morris than a domestic object. (Tellingly, Owens shows his designs with Salon 94, a New York gallery that formally opened a design program last year.) Everyone now is an artist, and anything is possible. There are cynical reasons for this, of course — art generally sells for more than furniture, so to blur the lines between a piece of furniture and a work of art means that a person can sell furniture for more money. But artists have long had a fascination with functional objects. The origins of the modern attempt to unite the decorative and the fine arts may lie with William Morris: English poet; maker of furniture, books and wallpaper; and revolutionary socialist. Working over the course of the late 19th century, he was inspired by a romanticized idea of the Middle Ages. Back then, before our fallen age, the figure of the craftsman and

41

A Chair for Twins to Intertwine by Faye Toogood When the London-based designer Faye Toogood was pregnant with her twin daughters last year, she found herself dwelling on the image of a double-yolked egg, which conveyed the squishy comfort of snuggling in a warm space. Living part of the year with her family in their country house in Hampshire, she would occasionally come across double yolks in the fresh, organic eggs there, reminding her of the serendipity that can happen when you embrace nature. ‘‘I really wanted to keep that feeling,’’ she says of this cotton love seat. Using canvas isn’t unusual for Toogood, though generally she has reserved it for her unisex garments; her furniture tends to be minimal and sculptural, rendered from materials like resin and fiberglass. But since she finished the twin seat she’s come to see it as a new prototype for furniture that brings a relaxed edge to her clean and rigorous aesthetic.

42

the fine artist were indissolubly united. Painting and sculpture had ritual func- functional of all: the Sussex rush-seated armchair, designed in the 1860s by tions, and the decoration of rooms was not reserved for specialists in interiors; Philip Speakman Webb. With the nostalgia embodied in its fine wood-turning, the names of artists, untethered from notions of auteurism and genius, were it was both profoundly simple and rustically handcrafted, syncretically calling considered obscure and unremarkable. It was, in Morris’s view, a freer time, with to mind rural chair-making of ages past. a more consistently beautiful standard of art. The market subverted Morris’s ideals several times over, and now the rush What had separated the artist and the craftsman, and relegated the designer chair sells for upward of $1,500 on 1stdibs.com. But his ideal persisted through to the category of the ‘‘lesser arts’’? For Morris, the answer was capitalism. It the 20th century, which was full of rearguard efforts on the part of the socially divided labor into infinitesimally smaller functions and thrived on creating minded to return furniture to the world of the arts. Walter Gropius, the founder of inequality between forms of art. Even within the practice of decorative arts, it A Chair to Freeze Time by Andrea Tognon made access to fine goods a luxury. If art The architect and designer Andrea Tognon works and lives in an industrial site at the edge of Milan that he has transformed into a verdant is ‘‘ever to be strong enough to help mangarden of Zen minimalism. He is dreamy and cerebral by nature, which animates his work for Céline’s retail stores, with their veiny pastel marble and contrasting corrugated metal. Little wonder one of his favorite books is Italo Calvino’s physics-rich short story collection ‘‘t zero,’’ kind once more,’’ Morris wrote in 1880, especially the title tale, which takes place in the mind of a lion hunter coolly estimating if the arrow he has just shot at a pouncing beast will ‘‘she must gather strength in simple plackill it before the lion can reach him. ‘‘It’s about extending mentally the value of a single instant of time infinitely,’’ he says. To make a chair that es.’’ Accordingly, one of Morris & Co.’s might convey that paradox, he cast a square concrete seat, a round base made from concrete with bits of exotic marble swirled in, brass hardware and a rounded back covered in fox fur. ‘‘To experience all these sensations simultaneously is a way to feel more alive in the moment.’’ most successful objects was the most

the Bauhaus school in Weimar, Germany, called the synthesis of arts and crafts ‘‘total architecture.’’ Artists entered the school and were trained to make flatware and lounges. From the world of industrial design, the spirit of the all-encompassing nature of design is captured in Charles Eames’s phrase ‘‘Everything is architecture.’’ The phrase seems to suggest that there are no boundaries to the scope of design. The lissome, molded plywood shells of his and his wife Ray Eames’s

43

lounges, partly rooted in Ray’s studies of abstraction in painting, evoke the visual space where design gives way to sculpture. These convergences between art and design through furniture reached their apex, as well as their dissolution, with the products of the Ettore Sottsass-led Memphis group in the early 1980s, at the onset of the era of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. These were lurid, insanely colorful objects that were nonetheless functional. Sottsass, trying to explain the wacky sensuality of the work, dubbed it a ‘‘cauldron of boilA Shelf at Last for the Great Books That Have Come With Me Around the World by Wonmin Park ing mutations.’’ The iconic Carlton bookcase’s Furniture designer Wonmin Park has never placed a premium on the easy comforts of home. He left his native Seoul at 24 geometric elements called up Art Nouveau; its base, after a few years in architecture school and, after a year in London, enrolled in the notoriously rigorous design program in Eindhoven, Netherlands. Although both his Dutch and English were shaky, he stayed in the isolated town for nine years, resembling concrete, quoted Modernism; its lamieventually developing his Haze series, geometric tables and chairs made from colored resin. Lately Park, who is now based in Paris, nate shelf-ends echoed the tackiest of kitchen has begun to work with aluminum, and for this project, mixed it for the first time with resin. ‘‘The perfect chance to find products. As with the American art world of the out how the two materials might interact was to make a place for these books that have inspired me through a very long road: Matisse, Brancusi, Serra, Carl Andre,’’ he says. ‘‘They are at the heart of my work.’’ ’80s, a commercial madness and media frenzy

44 166

A Chair to Practice Ascetic Discipline and Reach Transcendence by Pedro Paulo Venzon Pedro Paulo Venzon drew on the history of his native Brazil while it was under Portuguese rule to create this chair. The designer says he is interested in ‘‘objects of damnation’’ and their relation to colonial history and punishment. The chair recalls Venzon’s signature sleek and minimal designs, and its purpose is to take whoever sits in it into another dimension of contemplation. Though given Venzon’s preoccupation with damnation, it is perhaps unsurprising that it is not meant to be comfortable. Occasionally one must suffer in order to transcend.