4 minute read

A definitive new book on beavers

CARLETON UNIVERSITY BIOLOGY PROFESSOR MICHAEL RUNTZ CELEBRATES CANADA’S NATIONAL SYMBOL

BY KATHARINE FLETCHER

Advertisement

“None of the countless hours I have spent in the wild have been more enjoyable or educational than those spent at beaver ponds. Beavers are fascinating animals to watch, and even if none are visible when you visit a pond, you never leave disappointed for there is always so much to see and experience.”

So writes Michael Runtz in the introduction to his latest book, Dam Builders: The Natural History of Beavers and Their Ponds (Fitzhenry & Whiteside, $45).

The book has about 400 full-colour images. “Most are mine,” Runtz said while we chatted over coffee at Westboro’s Bridgehead, but a few required permissions – reproductions of contemporary logos from Parks Canada and Roots, plus the crest of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Old and recent, these visuals of the animal show how beavers have become a cherished national symbol of Canada.

No wonder. Beavers are perceived as industrious creatures who live companionably in social groups – qualities we Canadians might say define us. Moreover, hats made from felted beaver fur became the rage in Europe, spawning the fur trade where coureurs de bois joined native peoples in trapping then shipping the skins from Canada’s hinterland to Montreal, Quebec City, and Europe.

Indeed, pelts set the standard of currency here, where beaver populations seemed inexhaustible. Runtz said, “The great naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton estimated that in the period from 1860 to 1870 more than ten million beavers may have been killed in North America.”

Europeans over-trapped beavers just as they overhunted bison: to the brink of extinction. Runtz explains in his book. “In the winter of 1828-29, trappers harvested a grand total of four beavers in 25,000 square kilometres of wilderness near James Bay, a reflection of the situation across the entire continent.”

All of which brings us to realize how amazing it is that the populations rebounded, often thanks to reintroduction of breeding pairs in protected places like Gatineau Park. Their re-established numbers are such that residents bordering the park or living inside it sometimes regret their rodent neighbours.

But notwithstanding blocked culverts and burst dams that wash out roads, Runtz conveys what amazing creatures they are. Who knew that beavers resemble hippos and alligators? Eyes, nose and ears of all three species are set on the upper part of their heads so they remain above the waterline as they swim on the surface. This enables full sensory perception to locate predators – and for beavers to use their strong, flat tails to slap the surface of the water to communicate danger.

To me, this slapping sound is an iconic “call of the wild.” Although not as hauntingly romantic as loon laughter, when I was a little immigrant girl getting used to her new home in Canada, beavers enchanted me. I sat still as a mouse, pond-side, trying to spy that V-shape in the water which signified a swimming beaver. As quiet as I was, often the beaver would sense me and with a slap of its tail and a splash of water, it dived. Then a delicious wait … would I see it again?

Runtz’s book captures this magical mood of nature, and wistfully suggests return our children to the wild, so they too can sit spellbound, listening to the dawn chorus of birds while searching for beavers.

He blends facts and photos adroitly, weaving a profile of Canada’s national symbol, and going as far as showing us how even an abandoned, dried up beaver pond becomes useful habitat for a host of other wildlife.

The Dam Builders is a splendid addition to Runtz’s 10 other natural history books.

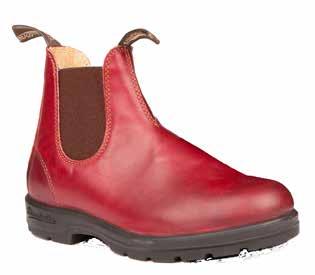

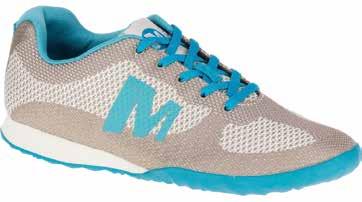

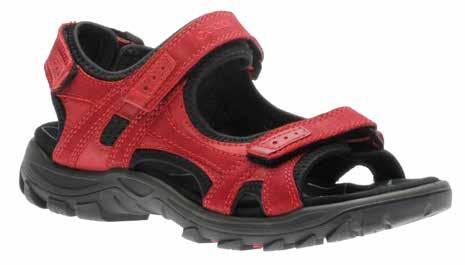

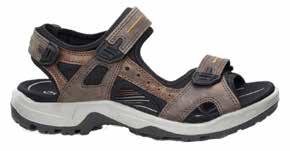

860 Bank St. (613) 231-6331 www.glebetrotters.com FOR THE PLACES YOU'LL GO.

FOOTWEAR FOR MEN & WOMEN