25 minute read

Weekend Getaway

WEEKEND GETAWAY CALABOGIE PEAKS RESORT This huge new development in the west part of Ottawa is going to be fantastic for the city. With everything from climbing walls and mountain biking trails, this resort is another close venue where outdoor enthusiasts can get out with the family for the weekend.

Here are the top 10 reasons why you want book your Weekend Getaway:

Advertisement

1.It’s less than 1 hour from Ottawa. 2.There is a scenic drive along the Madawaska River (especially this fall). 3.As you drive into the resort you are in awe of the size of the resort as it stretches from the top of Ontario’s highest vertical ski hill, down through the “Adventure Centre”, across the golf course and fi nally to the beachfront. 4. Beautiful landscaping covers the resort with fl oral colour explosions tastefully and generously spashed throughout the resort. 5. Although well known for winter recreation, Calabogie Peaks Resort is fast becoming a hot spot for biking, summer kids’ camps, golf, and whole family getaways. 6. Great diversity of things to do - biking (hardcore or softcore), climbing wall, golf, paddle, swim, hike, relax... all on-site. 7. Great place for a family holiday. The family can have a chance to participate in lots of activities together. Mom and Dad can also have a “night off” by enrolling the kids in the “Taste of the Outback” two day (and overnight) Adventure Camp. 8. Terrifi c rental fl eet availability — bikes, watercraft (canoes, kayaks, paddleboats). 9. Great location – surrounded by lots of cultural and historical points of interest. 10.NOW OPEN — the “Inn at the Peaks”. Beautiful, family friendly complex. Large rooms and suites, indoor pool, games room, fi tness room, restaurant and Spa. Stay & Play packages are available throughout each season. It’s already proven itself to be a popular spot for both weddings and corporate conferences.

Mill Pond Conservation Area: Exploring Nature’s tranquil moods

By Bev Wigney

Tok-tok-tok.

The hollow sound of knocking echoes through the woods. You scan the trees for its source. Clinging to a tree trunk, a Pileated Woodpecker in search of insects works intently, excavating a hardwood snag. Bark and shredded wood chips hurtle down into a rapidly growing heap at the base of the tree.

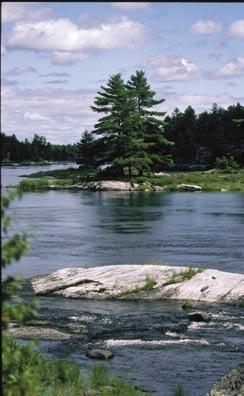

The woodpecker pauses, cocks his head on one side to regard you momentarily, then continues probing and tearing with his great beak at the decayed wood. Leaving him to his work, you continue your hike across a woodland ridge. From this vantage point, a break in the forest canopy provides a clear view of the silvery waters of Mill Pond. A pair of loons cruise by between the shoreline and one of several rocky islets dotting the shallow lake.

Little more than an hour’s drive from Ottawa, Mill Pond Conservation Area offers over six kilometres of soul-soothing hiking trails through habitats ranging from mixed hardwood forest to wetlands. It offers a perfect escape from the mad city pace, and puts you in touch GO THERE with the gentle face of nature. The main From Ottawa, drive to Smiths hiking trail forms a Falls, then head 15 kilometres long loop, roughly south on Highway 15. When following the irreguyou reach Briton-Houghton Bay lar shoreline of a Road, turn west (right). Travel shallow lake known approximately fi ve kilometres on this road, then watch for the Mill Pond Conservation Area sign and entrance on the west (right) side of road. as Mill Pond.

From the parking area, the Lime Kiln Trail bypasses a log house and seasonal 1 2 O T T A W A O U T D O O R S F A L L sugar bush operation before winding over gently rolling ridges and through hardwood forest. The Want more information? For more information, contact the Rideau Valley Conservation Authority at (613) 692-3571 or 1-800-267-3504. Their web site address is: www.rideauvalley.on.ca.

trail descends to a pond where neatly severed trunks of saplings reveal the presence of an active beaver population. If you watch quietly for a few moments, you may spy a muskrat paddling about as it feeds on aquatic vegetation, or see a beaver hauling a branch across the surface to its lodge.

Search carefully for leopard and green frogs hiding among the tangle of jewelweed, nodding bur marigold, and swamp milkweed at the path’s boggy border.

From the pond, the trail leads upland into a mixed deciduous forest interspersed with small stands of plantation and naturally occurring conifers. A short footpath leads off to the right to the lime kiln. Here and there, remnants of split rail fences serve as a reminder of the early settlers who worked this land.

Among the rolling ridges with their stony outcrops, you’ll see many great old trees rising head and shoulders above the surrounding forest. Watch for the smooth, silvery bark of the American Beech, and the feathery, flat-needled fronds of the Eastern Hemlock. Along the trail, a wonderful stand stand of large of ge Eastern White Cedar clings to the steep hillside overlooking the lake below. Much of the forest has been left to mature.

Along the pathway you’ll notice standing tree snags have been excavated by industrious Pileated Woodpeckers in search of ants and other insects. Other birds and small mammals have made their homes in these convenient hollows, or built nests in the treetops. Watch for them skittering about the woods.

On the forest fl oor, fallen trees are left to decay and act as nurse trees for the next generation of seedlings.

If you inspect these fallen giants, you’ll discover that they are hosts to a fantastic array of mosses, lichens and fungi.

As you hike through the forest at Mill Pond, watch for tracks, scat and other signs of larger mammals. Occasionally in springtime you’ll spy porcupines manoeuvring ponderously through the treetops, gnawing on tender twigs and budding leaves. Along the shoreline, opened shells of fresh water mussels lie in caches on the stones, abandoned by feeding muskrat. Look for them. They tell an interesting story.

At the top of a rocky ridge, the trail splits. If you take the left fork, you’ll be on the more direct trail back to the parking area. However, straight ahead lies the more scenic path along the shoreline – a meandering loop. It soon rejoins the “short cut.” Take this longer route to see the marshy edge of the lake from several vantage points. You might see Great Blue Herons wading in search of frogs, or perhaps a few Painted Turtles basking on bits of driftwood among the cattails. The The final nal leg leg of the of the hike hike leads leads along along a a roadway back back to to the the parking area at the entrance gates. On your right, you’ll see a small meadow that serves as an access point for paddlers bringing canoes and kayaks kayaks to to Mill Mill Pond. Pond. While While the the surface area of Mill Pond is not great, its shallow waters and rocky, irregular shoreline offer an interesting location for a couple of hours of aquatic exploration.

With its woodland trails and quiet waters, Mill Pond Conservation Area offers a great outing for naturalist hikers or paddlers. Explore its changing beauty in all the seasons.

—Bev Wigney lives in Ottawa and works as a freelance writer when sheʼs not out on the trails.

stay safe while kayaking

By Ken Whiting

Shoulder dislocation. These words send fearful shivers through most kayakers.

Why is a shoulder dislocation so dreaded by kayakers? The pain factor doesn’t seem to drive fear into our hearts. It’s the thought of having to go through surgery, the thought of sitting idle through months of therapy, and the thought that the shoulder will never be as strong as it had been.

These are substantial concerns. A shoulder dislocation is often accompanied by damage in the joint that requires real care, and sometimes surgery, to heal. So let’s look at ways to keep your shoulders safe.

Having well-conditioned muscles around the shoulder will go a long way to keeping your joints in place. Paddlers often have much stronger back shoulder muscles than front shoulder muscle. That’s because you use primarily back muscles for forward paddling. Because most shoulders dislocate forwards, your front muscles should be equally as strong as your back ones. This is where back paddling practice comes in.

Even with Superman’s shoulders, a dislocation can happen easily. Here are two simple rules to protect you: • Don’t overextend your arms. • Maintain a “power position” with your arms.

Rule number one is easier said than done. When you’re tossed around in whitewater, a desire to keep your head above the water can easily override safe paddling practices. Stay as relaxed as possible, and fi ght the urge to use massive “Geronimo” braces.

What’s the “power position” in rule number two? Imagine looking at your body from above. Now draw an invisible line that passes through both shoulders. This is the “shoulder line.” Now draw another line that divides your body into two halves – the “mid line,” parallel to your waist. The power position simply involves keeping your hands in front of your shoulder line and preventing your hands from crossing your mid line. In so doing, you will maintain a rectangle with your arms, paddle and chest. Within this rectangle you’ll get the most power from your paddle and keep your shoulders in the safest position to avoid injuries.

When your hands move behind your shoulder line, your arm is in a very vulnerable position. Does this mean that you can’t safely reach to the back of your kayak? Not at all. But what it does mean is that in order to reach to the back of your kayak you’ll need to rotate your whole torso so your arms stay in the power position. Torso rotation keeps your shoulders safe, and it’s a key concept for getting the most power from your strokes.

Now that you know the theory, get out on some water and practice it. Play is healthy.

— Ken Whiting was the 1997/98 World Freestyle Champion and has produced an award-winning series of instructional kayaking books and videos. As well, he leads kayaking trips to Chile, for more info check out www.playboat.com.

Safe shoulder draw: A powerful open face bow draw (duffek), with the head and torso rotated aggressively to keep the arms in the power position.

Bad shoulder line: Poor Torso Rotation: the rear hand falls behind the shoulder line, and the front hand crosses the mid-line.

Good shoulder line:

The Power Position: The whole upper body turns so the hands stay in front of the shoulder line; neither cross the midline, and the arms, paddle and chest form a rectangle.

CANOEING

A Tale of Two Rivers:

By Max Finkelstein Photos Paul Chivers

TWO RIVERS in the Ottawa area (the French and the Mattawa) especially conjure up images of French Canadian voyageurs racing back to (Lachine) Montreal through the wilderness with their precious cargoes of beaver pelts and fox skins.

Can you hear the soft murmurings of their ghosts?

As I dip my paddle into the waters of the French and Mattawa Rivers (both designated Canadian Heritage Rivers), my imagination takes fl ight. I hear cursing voyageurs toiling over slippery portages, and see them hauling their birchbark “canots de maitre” past foaming rapids and waterfalls, swatting clouds of hungry mosquitoes, while they hurriedly slide their delicate crafts back into the water over glacier-polished Canadian Shield granite.

The French and Mattawa Rivers formed a vital link in the fur trade route from Montreal to Lake Superior and the Northwest. They helped open the heart of Canada fi rst to economic exploitation and exploration, then to settling pioneers.

Today, recreational paddlers follow portages unchanged for over 300 years.

Following the Path of Ancient Paddles

The French River fl ows between Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay. In 1986, the French’s entire 110-kilometre length was designated part of the Canadian Heritage Rivers Systems – the fi rst river in the program. Its rich fur trade history and unaffected appearance earned it this honour.

Glacier-carved rock and windswept pines characterize the route. In many ways, the French River today looks the same as when Alexander Mackenzie paddled on it over 200 years ago – the fi rst person to reach the Pacifi c coast of North America travelling overland. (Mackenzie accomplished this amazing feat 13 years before the much-vaunted, transcontinental expedition of Lewis and Clark through the United States.)

“There is hardly a foot of soil to be seen from one end of the river to the other; its banks consisting of hills of entire rock,” wrote Mackenzie.

Several years ago, paddling down this river on my own crosscontinental trek, I wandered in the rain on a small island in the river’s path. There, several rough wooden crosses stood as quiet sentinels

commemorating the martyrdom of Recollet missionaries four centuries before. History abounds on this river. Although the French is one of Canada’s most popular canoe routes in summer, on that cold, wet spring day, with the water black and icy, I was the river’s only paddler.

Where’s the most beautiful part of the French River?

You’ll fi nd it downriver from the steel bridge at Highway 69. Downstream from this bridge, the river is framed by vertical cliffs of smooth pink granite. The patterns formed by gray, green and orange lichens are mesmerizing. My only portage came at beautiful Recollet Falls. You’ll fi nd a wooden ramp built around the falls along the route of the old portage; this permits motorboats to use the river. For the voyageurs, running downstream on the French proved an easy one-day paddle.

The water coming over the falls fl ows smack-dab into a vertical rock wall just below the put-in, forming a huge eddy. Voyageurs in their heavily loaded craft experienced some anxious moments here. I had a tense moment in this location too, as the eddy tried to sweep me over the falls. It’s easy to understand why many canoes have been lost here over the years.

The mouth of the French River is like no other landscape on the planet. The river splits into four main channels with cross channels, so it looks like a city street map. It’s a landscape reduced to simple elements: rock, water and pine trees. But there’s a lot more here than the most beautiful scenery imaginable. You’ll find relics of the logging era along the river: rusting hulks of “alligators” (amphibious, steam-driven mobile winches used to move logs), and stone walls of a mill at the old town of French River – now long deserted.

Mackenzie followed the standard fur trade route, still identified on topographic maps as the “Old Voyageur Channel.” In this maze of rock and water, the correct channel is hard to find, especially since the critical split lies almost exactly on the edge of the two topographic map sheets that all paddlers use today. I almost always get lost going from one map sheet to the next.

The channel I followed on that trip seemed like the one Mackenzie took.

In the words of this great explorer: “…In several parts are ‘guts’…where the water flows with great velocity, which are not more than twice the breadth of a canoe.” This is near the end of the river.

I slid over “La Petite Faucille” (the only portage noted by Mackenzie), and was flushed down “La Dalles” (loosely translated as the eaves trough – an apt description) to Georgian Bay. It’s an amazing ride, as the river is squeezed between smooth rock walls.

Whenever and wherever you paddle the French, it is a magical river, steeped in history and some of the most amazing scenery in Canada. Try it this fall.

Mattawa Paddling Bliss

Another favourite river of mine is the Mattawa. It rises in Trout Lake, and drops 50 metres over its 60- kilometre course to the Ottawa River. The entire Mattawa River, including the 11-km La Vase Portages – one of Canada’s most important portages – is designated a Canadian Heritage River. It is also a provincial waterway park. All the portages are maintained and identified with interpretive signs.

Those paddlers lucky enough to sit in a rocking canoe on the Mattawa today see the river much as the voyageurs did long ago. The river has only two small dams. The largest is near the town of Mattawa, and has drowned out the first two rapids. Otherwise, the rapids and, most important, the original 14 portages, are still there. This river makes a great little canoe trip, especially when you’re going downstream.

Each summer, a marathon canoe race is held on the Mattawa. The top racers paddle the entire route from the end of Trout Lake to the dam above the town of Mattawa (a distance of almost 80 kilometres) in less than six hours!

You wouldn’t guess that the little Mattawa River was once part of the trans-continental fur trade route. Compared to the mighty Ottawa River, the Mattawa appears but a minor stream. Alexander Mackenzie considered “la petite riviere” one of the most dangerous in Canada. Here’s how he described the Mattawa’s Talon Portage: “275 paces… for its length… is the worst on the communication; Portage Mauvais de Musique… where many men have been crushed to death by canoes.…”

On my own transcontinental journey up the Mattawa in spring, I identified with Mackenzie’s view, and that of thousands of voyageurs who toiled up this little river. When I paddled along it, a cold, slimy, pouring rain slithered off the brim of my beat-up, oiled-cotton hat, where I stopped to read a bronze plaque identifying this as one of Canada’s most significant waterways.

Later, I slipped on the same rocks the voyageurs had, waded through equally cold icy water – just as they had – sweated and froze at the same time on the portage around Talon Falls. I climbed the steep ice and rock slope to a cave, the “Port de l’Enfer” (loosely translated as the “Door to Hell”), where ancient native peoples mined red ochre, a pigment rich in iron oxides, to draw pictographs that I saw much farther on in my journey.

Later, I stopped for a hot lunch at Paresseux Falls – a spectacular curtain of white fed by spring floodwaters. Here, I reminisced about how it got its name. I don’t know whether to believe it or not, but according to historical lore a brigade of voyageurs lost a canoe at this set of falls early one spring, so they left behind two men with the salvaged gear. The rest of the crew returned to Montreal to get a new canoe. The two voyageurs left at the falls were instructed to portage all the salvaged gear to the top of the precipice. When the crew returned two weeks later with a brand-new “canot de maitre,” they found their companions and all the gear still at the bottom of the falls – hence the name “Paresseux,” which means “lazy ones” in French.

I felt lazy myself at this place, as I sipped hot chocolate with the music of falling water playing around me. But cold and dampness drove me onwards up the river after the warmth of the hot chocolate had dissipated.

Pushing my canoe back into the water, I continued my journey around rapids, falls, and wet canyons where snow and icicles hung from black rock walls. Not long afterwards I noticed a cedar tree standing on a steep bank, partly covered with ice. It looked like some ice-age relic.

At Talon Falls I carried my canoe over the steep, slippery rocks around the falls, and the much easier carry called Anse des Perches – the last section of fast water on the trip to Grand Portage. Here, the voyageurs threw away the three-metre long setting poles that they used to nudge their big canoes up the rapids. I fi nally pitched camp at the foot of Turtle Portage, and watched the rain turn to snow.

A small, inconspicuous divide separates waters fl owing into the Ottawa River watershed and waters fl owing into the Great Lakes. The divide lies between Trout Lake – the head of the Mattawa River – and Lake Nipissing. Eleven kilometres separates Trout Lake from Lake Nipissing.

As this was the main fur trade route, it must have been a well-trodden trail when Mackenzie passed through the area. In his dry, matterof-fact tone, he described the portage: “(O)ne thousand, fi ve hundred and thirteen paces to a small canal in a plain that is just suffi cient to carry the loaded canoe to the next vase… a narrow creek dammed in beaver fashion… (A) swamp of two miles to the last vase…. (C) are is necessary to avoid the rocks and stumps and trees.” (It sounds as if Mackenzie uses the word “vase” to mean “portage,” but I think he meant a slimy, muddy trail. In French, “vase” means “muddy.”)

This portage route is one of the oldest known trade routes in Ontario, if not all of Canada. But today, not a trace of the old portage remains. It’s hard to imagine that this was the TransCanada highway used by aboriginal peoples for thousands of years.

For a real “voyageur” experience, paddle both the Mattawa and the French. These rivers carry you into Canada’s colourful, fur trading history. Sometime during your own journey on this historic water, take time to listen closely. Can you hear the songs of the voyageurs?

—Max Finkelstein paddled his canoe across Canada several years ago. He works for Parks Canadaʼs Canadian Heritage Rivers System. Last summer he paddled across northern Quebec re-tracing the routes of geologist and explorer, A.P. Low – the subject of Maxʼs next book.

The Canadian Heritage Rivers System

The Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) is a national program for rivers managed cooperatively by the Federal Government, through Parks Canada, and all ten provinces and three territories. Its objective is to give national recognition, and provide long-term wise management, to rivers that have played a signifi cant role in Canadian history, and those that have outstanding natural features and value.

The CHRS has a video entitled “Community Refl ection on Canadaʼs Heritage Rivers” that is available for the public. To get a copy, call the Secretariat at 819-997-4930; e-mail: max.fi nkel stein@pc.gc.ca; or write to the CHRS Secretariat at Parks Canada, 4th Floor, 25 Eddy Street, Hull, Quebec, K1A 0M5.

For general information about the Canadian Heritage Rivers System, surf to their web site at: www.chrs.ca.

ACTION

Help wanted with portage restoration Are you interested in helping to restore some of Canadaʼs ancient portage trails? Some paddlers living in North Bay have formed a group called, “Restore the Link Committee.” It is dedicated to re-establishing the 11-km portage route that separates Trout Lake from Lake Nipissing. The goal: restore it to its original (200 years ago) state, and clearly mark it so that once more paddlers can use the trail as a portage route. For more information on the La Vase Portages and the Restore the Link Committee, contact Paul Chivers (pchivers@neilnet.co).

REQUIRED READING

Canoeing a Continent Max Finkelsteinʼs outstanding book describes his transcontinental canoe trip following the route of wilderness explorer Alexander Mackenzie. More than just a travelogue of an amazing canoe trip across Canada, this book digs in to the heart and mind of one of historyʼs greatest explorers. For a copy ($25.95), call 1-800-725-9982 or send an e-mail to info@naturalheritage books.com.

Hook your kids on Canoe camping

By Peter McKinnon

When my wife was six months pregnant with our first child, we paddled into Algonquin Park for three glorious nights at a remote campsite. While both of us loved canoe camping, we recognized that this might be our last trip for a few years.

While in the park, though, we met a canoe-tripping family with two children under the age of seven. We resolved to ensure that our children came to share our passion for paddling. Today, thanks to advice from trippers and outfitters, our two boys (Kieran, 11 and Grady, 8) have grown into avid canoe-campers.

Photo by Peter McKinnon

The principle pleasure of a canoe trip, particularly for a child, is swimming. A summer frolic in pristine waters is a primordial celebration of Canada. And while experience can teach us to savour the scent of a forest, the feel of a canoe slicing through the waves and the splendour of the night sky, a refreshing swim is the surest way to capture a child’s heart.

Here are a few tips, tricks and itineraries that will help you inspire your children to follow in the path of the paddle.

Basic Strokes

If raising children is a test of patience, taking them canoe camping tests endurance. Don’t expect every outing to be a success; cut a trip short if the weather fails to cooperate. Start gradually by tenting in the backyard and work up to car camping and brief outings in a canoe.

Recognize that Junior may need time to appreciate the subtle charms of bugs and box toilets, so focus on playful swims and simple adventures. Swallow the purist pride you developed as a carefree, ardent naturalist, and hone improvisation skills.

On our first car-camping trip, for instance, we found it a struggle to put our kids to sleep; they had learned early-on that a tent is an ideal place for play. They were also used to falling asleep by 8 p.m. in darkened rooms – tough to recreate in a campground.

Mixing sleep-deprived children with sun-baked adults is a recipe for family crankiness. Do whatever it takes to ensure that everyone gets enough rest. That might mean taking afternoon naps or foregoing evening campfires. Often I have buckled our youngest into his car seat for an evening drive around the campground to induce sleep. While it may have been environmentally unfriendly, it was vitally important to my continued sanity.

Charting a Safe and Happy Course

Safety, of course, is always the overriding concern. Take a course in basic lifesaving and first-aid techniques, and insist your children learn to swim. Establish rules, then enforce them strictly: young children should never handle a hatchet, and must always wear lifejackets while in the canoe.

There is no minimum age for a child’s first bona fide canoe trip; it’s up to mom and dad. Someone once said that a child is old enough when he or she has enough sense to avoid walking into a campfire or plunging into untested waters. Many adults wouldn’t meet that standard.

Successful canoe trips rely on a unique mixture of deliberate planning and uninhibited spontaneity. A sudden storm or an unsuitable campsite, for instance, is enough to throw an itinerary out of whack; a leaking package of food can disrupt a meal plan. Here’s the secret… prepare for the unexpected, then surrender to the whims of nature. Arrange every last detail in advance, then, once underway, relax, go with the flow and be ready to throw away the plan.

Food: Always pack more than you’ll need; a hungry child is a whiny child. Be sure to include lots of travel treats (e.g. fruit leathers, candies, gum). If you’re forced to set up camp in a hurry, these can buy you enough time to erect a tent, light a stove or filter water.

When it comes to cooking, simplicity is bliss. Gourmet meals may be tasty, but often require lots of preparation time. Plan nutritious, filling meals that can be prepared quickly, easily and flexibly. You should be able to prepare every hot meal on a simple camp stove. During the first night of a trip into Bon Echo Park, a fire ban came into force, and we had to pan-fry rather than grill our chicken breasts. A few extra spices made all the difference. Equipment: Local outdoor stores offer a wide selection of equipment at very reasonable prices. While the essentials will keep you warm, dry and well fed, it is the few carefully chosen extras that make a trip memorable. Here are some examples… I always pack binoculars, a camera, tasty campfire snacks, and (space permitting) my guitar. My kids love to

wear goggles when they cavort in the water, so they can feel like one of the fish. Your “essential” options are limited only by fragility and weight.

Where to Dip Your Paddle

Canoe routes are like real estate: location is everything. And few locations in the world offer the abundance of routes available near Ottawa. From calm, scenic lakes for beginners, to spectacular roiling rapids for experts, Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec feature a smorgasbord of sumptuous options. Arranged in order of difficulty, following are a few locations that I’ve had the pleasure of sampling.

Gatineau Park is an ideal spot for beginners. Lac La Pêche’s 35 campsites are only a 10 to 20 minute paddle from the parking lot and boat rental hut. Should the weather (or bugs) turn nasty, you can beat a hasty retreat. Unfortunately, La Pêche’s most popular sites are booked months in advance.

A two-hour drive from Ottawa, Bon Echo Provincial Park can be a wonderful introduction to canoe camping. Joeperry Lake features 25 campsites within an hour’s paddle