8 minute read

Bill Mason:

R emembered

By Ken Buck

Advertisement

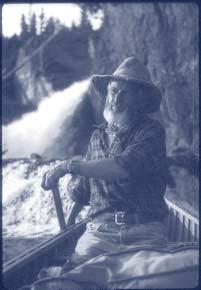

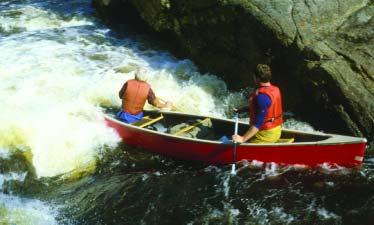

AS BILL MASON slips his canoe into the early morning calm, the canoe cuts silently through the water and is swallowed up by the mist. The sun is just breaking over the horizon and beginning to create a diffused light, giving suggestions of details along the shoreline. Soft silhouettes of trees take shape overhead. This is not a shot in one of Mason’s famous canoe films. For Bill Mason it is just another day at the office, or to be more precise, his commute to the office. It is 1958 and Bill has just moved to Ottawa to work for Budge Crawley as an animator. It was Bill’s plan to rent a cottage at Meech Lake, but none was available, so he set up camp on the north side of the lake and commuted by canoe and car to Crawley’s every day for about six months. This was Bill’s idea of heaven—to have to commute to work by canoe. Fortunately, one of Mel Alexander’s log cabins came up for rent and Bill could move under a roof for the winter. Actually, he would have been glad to stay in the tent, but he also married Joyce Ferguson in 1958, and he needed a home. They lived at Meech Lake until Bill died in 1988.

Bill went on from Crawley Films to become one of Canada’s most prominent documentary filmmakers. Through his films he became a powerful spokesperson for the growing environmental awareness in Canada, and indeed the world. His two documentary feature films, Cry of the Wild and Waterwalker, are among the most successful feature length films ever made in Canada.

It’s been 14 years since Bill Mason died of cancer at age 59. The fact that his name, and his films, and his influence have endured is a testament to his lifelong effort to protect the natural world from careless and destructive exploitation. His ideas, provocative and progressive at the time, have proven to be wise and insightful. Most of his ideas underpin our collective sense of environmental ethics. His first concern was protection of Canadian natural resources, but his scope was global and universal. Bill knew the power of story telling, especially through film, and it was through his stories that he put Canadians in touch with the Canadian wilderness.

Few people have had the influence that Bill Mason has had in shaping the Canadian identity. His films, produced at the National Film Board of Canada, have been mainstays in Canada’s schools for the last fifty years. Educators have used his films—Paddle to the Sea, Rise and Fall of the Great Lakes, Wolf Pack, Death of a Legend, Path of the Paddle, Face ofthe Earth, and many others—to introduce two generations of students to Canada’s wilderness and the concept of environmental stewardship. Bill’s vision of the wilderness as benign, beautiful and precious effectively offered an alternative to the predominant cultural perception of wilderness as something to be feared, to be conquered and to be exploited.

Because many of Bill’s films were autobiographical, he was in them and he became a familiar face to many Canadians. Bill acquired a profile of iconic proportions in his role as an environmentalist and outdoorsman. This profile has become legendary since his death.

Few know the whole story behind the famous filmmaker and environmentalist.

In his youth, as Bill became more and more attuned to environmental responsibility, he used his art to encourage environmental responsibility in his audience. He took every opportunity in his commercial art and his photography to show Canadian wilderness to Canadians.

After graduating from the University of Manitoba and starting his commercial art career, Bill was able to go on extended canoe trips. He went away for six months at a time. He often canoed solo, over the well-intentioned objections of just about everybody. It was these extended solo trips that gave It was as simple as that in his mind, and every scene in every film had that idea as its starting point.

Bill plenty of time to contemplate man’s place in nature.

The single most powerful compelling force behind Bill Mason’s commitment to environmental responsibility was his deep unwavering Christian faith. Bill believed that man did not have “dominion over” the natural world, but “responsibility for” the natural world. God’s creation was not put there for man to destroy and abuse.

If you go back and look at his commercial art from the fifties and sixties you can see that he is probably the only commercial artist who could sell a product, and at the same time teach a lesson in Canadian history and environmental ethics. Many of his ads sold the product by associating it with facts from Canadian history, or with the value of pristine wilderness. His clients had provided Bill with a platform from which he could advocate his vision. Like the best of teach

ers, the main point of his “lesson” was in the unspoken analysis and reflection. If you look at all his films, this multi-layered agenda of entertaining and teaching is used in every one. And often, the most important part of the lesson is that part which remains unexpressed but perfectly clear.

At the same time, Bill’s clients loved the work that he did for them. He became a respected and sought after artistic director for advertising firms. His advertising sold product as well as environmental ethics.

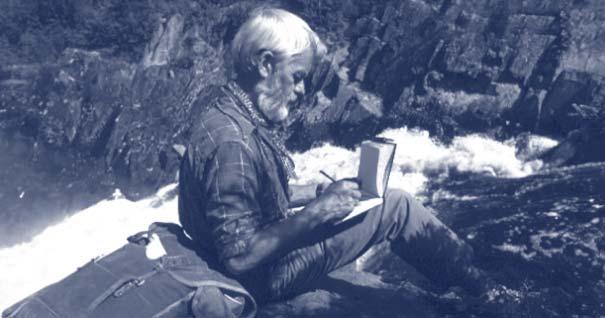

Before Bill went on his extended canoe trips, he would quit his job. To be more accurate, every year he asked for six months off without pay—which was always refused. Then he quit his job. When he came back at freeze-up, they always hired him back. During these trips Bill shot photographs of his beloved wilderness. He used a simple Rolleiflex camera and he shot 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 slides. He became well known in his native Winnipeg because of his slide shows. He was invited all over the city to show them. It was his way, as an artist, to advocate environmental

responsibility. He worked on the premise that if he showed people how beautiful the wilderness is, they would inevitably become responsible environmentalists.

This slide show, The Timeless Wilderness, was what connected Bill to his first film job. In 1956 Chris Chapman (A Place to Stand, Ontario pavilion, Expo 67, Academy Award winner for best short film 1968) had a contract to make a film about Quetico Provincial Park. He needed an assistant who knew how to live in the wilderness and who could also play the part of the canoeist. He heard about Bill from some one who had seen The Timeless Wilderness. He hired Bill, and one great Canadian documentary filmmaker launched the career of another.

Bill’s rise to success as a filmmaker was meteoric. The very first film he

made for the National Film Board of Canada, Paddle to the Sea, won eleven national and international awards and was nominated for an Oscar (Best Short Film) in 1968. One of life’s little ironies: he lost to his mentor, Chris Chapman, A Place to Stand. By the mid-seventies, Bill had become one of Canada’s most successful documentary filmmakers. Two years later Bill was nominated for a second academy award for best short film for his documentary Blake.

Bill’s influence was not confined to Canada. Several of his films have been translated into several languages. Queen Elizabeth showed Paddle to the Sea at one of Princess Anne’s birthday parties and wrote Bill to express her pleasure at how well the film was received by the children.

Every Canadian who is a canoeist or an environmentalist will be familiar with his name. Bill’s favorite red Prospector canoe shares a display area in the Canadian Canoe Museum (Peterborough, Ontario) with Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s birch bark canoe. His films were consistently among the ten most frequently rented films from the National Film Board of Canada. For several years he had four films in the top ten—an amazing feat. He has a total of 28 international film awards. He was accepted into the Royal Academy of the Arts in 1974.

Bill retired from film making in 1986 to pursue his first love—painting. With his very high profile success as a filmmaker, it was easy for people to forget his first love was painting. He had been experimenting with a new technique—oil applied to paper with a palette knife—and he was ready to strike out in a new career as a fulltime professional painter. He divided his time between writing and painting for a few short years. But Bill’s career as a painter was cut short by his untimely death in 1988 at age 59.

Many words have been published about Bill’s life and art, but an artist’s story is not complete until it is told through his art. The legend of Bill Mason is best illustrated and understood by seeing all his work. His commercial art, his still photography, his films, his books and paintings have become cultural touchstones for all Canadians. His art explained to Canadians why they should be environmentalists. His canoe films invited a whole generation to get in touch with its national roots by travelling and living in the wilderness. Seldom has any single Canadian artist had the hearts and minds of so many admirers; and seldom has any single Canadian been so influential in creating a sense of responsibility for our environment.

Excerpted from Ken Buck’s book in progress Bill Mason: Wilderness Artist, and previously published in part in CanoeRoots, Rapid Magazine’s annual Canadian canoeing magazine. About the author: Ken Buck started teaching English in Ottawa in 1968. He resigned from teaching in 1974 to work full time with Bill Mason as his cinematographer and general assistant.