4 minute read

Geoff Keller

courtesy photos

~by Jeff Tryon

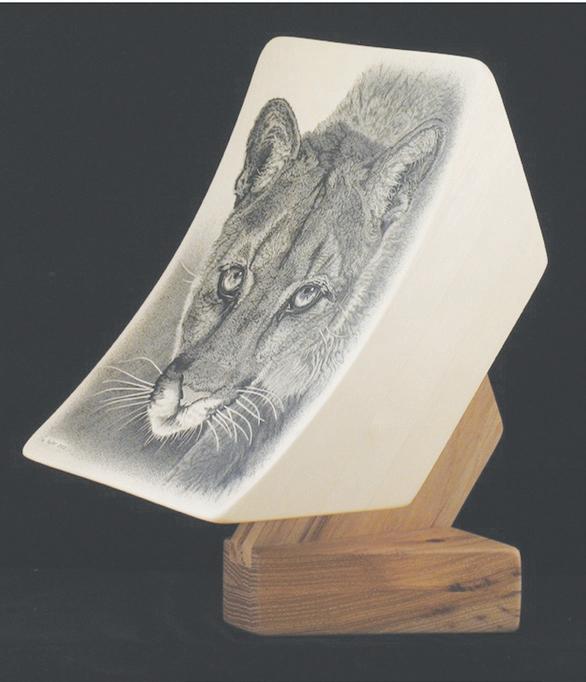

Geoff Keller spent over 20 tools, but mostly a wood rasp and California woman named Alice years traipsing up and sandpaper. Cahill. “I found her image of a down the North American Then he meticulously creates mountain lion’s face, and it was Continent recording songbirds. the drawing by applying thousands just so exquisite, I thought, I’ve got

But a bad reaction to a doctor’s of tiny ink dots to create the to draw this.” The mountain lion prescription and a chance encounter image of a bird or other animal piece took over three months to with a book about how our brains from a photograph. The artwork is complete and involved creating a work led him into new way of protected between ultra-thin coats new technique of blurring the dots presenting birds—as ink drawings of poly acrylic so that it can’t bleed to represent soft fur. on wood sculptures. into the wood or be smudged after it For 24 years, Keller recorded birds

You can see the amazing results is finished. for Cornell Lab, which has the largest at the Hoosier Artist Gallery on “What I’m doing is actually archive of wildlife recordings in the South Jefferson Street, where Keller’s portraiture, I’m working from world. painstakingly wrought, intricately photographs taken by professional “I have probably archived more detailed artworks are offered for photographers,” Keller said. He has high-quality recordings of North sale. most often drawn on the images of American birdsongs than any

Keller laminates layers of lightregional photographer Steve Gifford. other individual in the history of colored Aspen wood into a large His most recent and ambitious the Cornell Lab,” he said. “During block, then carves it into a vaseproject is the image of a mountain that time I archived about 3,000 like sculpture using some power lion’s face from a photo by a recordings.”

In the process, he trekked everywhere from the Florida Everglades to the sub-Arctic above Nome, Alaska and from about 800 miles south of the Mexican border to the ocean cliffs of Newfoundland, and a lot of places in between— swamps, forests, prairies, mountains.

However, at age 55, he lost his high-frequency hearing due to a bad reaction to a drug he was given for a sinus infection. From that point on he could not make as clear of distinctions between the sounds, and didn’t find his efforts as rewarding.

Trying to reinvent himself, Keller recalled his childhood fascination with woodworking. He began by making hiking sticks and drawing little ferns on them. “They were pretty primitive looking, but I was having fun,” he said. “Then, I was at the bookstore at the Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge near Seymour. They had a book called Illustrating Nature: Right Brain Art in a Left Brain World. The book said there are people who are really talented in art, but they lead their whole lives without realizing it, because every time they try to draw, their left side overrides overrules the right side. So, basically, I drew like a fourth grader until I was 60, and got this book,” Keller said. “I was fascinated with it, and I followed these simple techniques for derailing the thought process of your left hemisphere, which allows the right hemisphere to express itself. And right from the get-go, I was drawing a frog, and I thought, ‘Where did this come from?’ I could draw!”

As he improved, he needed a bigger canvas than walking sticks, so he created wood sculptures that provided about an eight-by-ten inch surface for the nature drawings. But, they are very labor intensive. “They are one-of-akind and I only do an animal once, so they have a fairly hefty price,” he said. “I just sold my first vase the other day.”

Most of the drawings are made up of tiny dots, kind of like the dots used to create photos in offset printing. “They are so tiny, it’s hard to perceive them as dots,” Keller said. “And the reason I can get them that small is because I’m super near-sighted. I wear contact lenses in everyday life, but when I take them out, my focal point is about three inches in front of my face.”

He uses archival ink pens with tiny nibs and has discovered that using a light touch and a pen that is starting to dry out produces the tiniest dots. He said the average piece takes about eighty hours, but the mountain lion far exceeded that.

“I think I worked for a week just on the eyes. They are getting more complicated,” he said. “Before the mountain lion I did a barred owl, and those two are by far my best examples. Through trial and error, I keep discovering new techniques, learning what works and what doesn’t work. “I’m always trying to think of ways to make the process more efficient.”

You can find more information on Keller’s art at Hoosier Artist Gallery’s website <hoosierartist.net> or drop by and see works in person at 45 S. Jefferson St. in Nashville.