www.outdoorcanada.ca

To enjoy non-stop yellow perch action this winter, you need a mix of both aggressive and finesse approaches. Whether the bite is hot or cold, these are the tactics and gear you need to ensure a successful day out on the ice.

outdoorcanada.ca/twowayperch

For fly anglers, the Caribbean offers thrilling action for exotic and power ful fish, but the switch to saltwater fly fishing can be jarring. Find out what to expect, and how you can prepare for a tropical winter getaway.

outdoorcanada.ca/tropicalflyfishing

From deep Canadian Shield lakes to shallow prairie reservoirs to the mighty Great Lakes, sharp-toothed walleye are Canada’s most sought-after sportfish. Not only are they challenging and exciting to catch through the ice, they also make for excellent table fare. Of course, walleye inhabit such diverse habitats across this giant country of ours that you have to be both versatile and adaptable to successfully and consistently catch them, changing your approach as needed from one type of waterbody to another. That’s where these 12 expert tactics from fishing editor Gord Pyzer come into play, guaranteeing to help you put more—and bigger—walleye on the ice throughout this hardwater season. outdoorcanada.ca/winterwalleyetricks

Outdoor Canada fishing editor Gord Pyzer regularly posts fishing tips, gear reviews and much more on his blog, “On the water online.” Check in often to stay on top of exciting developments in the world of angling. outdoorcanada.ca/blogs

Coyotes are smart and always on high alert—even the smallest mistake can make your hunt go south in a hurry. Here are five common coyote-hunting blunders, complete with advice on how to avoid them.

outdoorcanada.ca/coyotemistakes

Once the norm before virtually disappearing in the early 1900s, singleshot rifles have enjoyed a recent resurgence. But are they the right choice for you? Hunting editor Ken Bailey examines the pros and cons. outdoorcanada.ca/singleshotrifles

Modern bowhunters can choose from an array of fixed-pin and dial-up sights, sights with retina alignment and even digital models. We go over the options to help you pick the best sight for your hunting needs.

outdoorcanada.ca/bowsightprimer

SEE US ON BELL, SHAW, TELUS, NOVUS, VIDEOTRON, SASKTEL, COGECO AND LOCAL CABLE PROVIDERS

SEE US ON BELL, SHAW, TELUS, NOVUS, VIDEOTRON, SASKTEL, COGECO AND LOCAL CABLE PROVIDERS

SPORTSMANCANADA.CA

SPORTSMANCANADA.CA

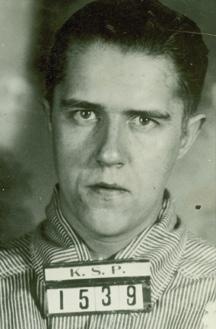

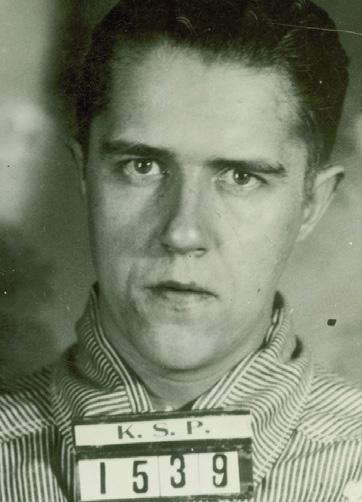

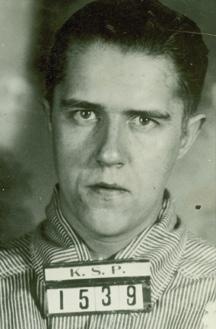

I noticed that my name is incorrect in the text associated with the picture of the Cobb family’s successful deer hunt (Trophy Wall, Hunting Special 2022). I’m the father-in-law pictured (second from right, above), but my name is Dave Hoover, not Dale. I’ve been a subscriber for years, and I love the magazine!

DAVE HOOVER NORTH BAY, ONTARIO

DAVE HOOVER NORTH BAY, ONTARIO

In each issue of Outdoor Canada, I always enjoy reading about what new products are available. In “Hunt helpers” (Hunt ing Special 2022), I found a product that was of real interest to me, the Shield Full Zip Jacket from Alps Outdoorz. Windproof, waterproof, fleece lining and a hoodie—perfect! I went to their web site, subscribed and they replied with a 50 per cent discount off my first order for subscribing. Although the price was in U.S. dollars, it was still too good to be true. Which it was. They don’t ship to Canada. I think your magazine should only show us stuff we can get up here. It only makes sense, since you’re called Outdoor Canada. Just a slight blip from an otherwise great mag. I would have liked that jacket, though.

TOM MILLER GREENHILL, NOVA SCOTIAThe editors reply: We’re sorry you can’t get your hands on the Shield Full Zip from Alps Outdoorz via their website. They will ship to Canada via phone-in orders, how ever, although you’ll have to pay shipping and duty costs, unfortunately. Cabela’s/ Bass Pro and Walmart in Canada carry Alps products, but it would appear to be

mostly backpacks. Another option would be Amazon.ca or Shopbluedog.ca, but again, their offerings may be limited. At any rate, again, our apologies for the frustration. On a lighter note, we’re happy to hear you enjoy the magazine. Thank you for reading!

NOT INCLUDED

I have read numer ous outdoor articles, and I find a lot of the fishing articles are redundant and lack informa tion. If a person is trying to learn, it is next to impossible. For example, you write about using and tying two-fly rigs (“Double duty,” Hunting Special 2022).

One would never learn, however, unless shown how to tie the rigs, and what items to use. It’s like those sponsored professional fishing shows showing a guy catching a fish, but not showing the lure he used. All you hear is, “Oh, that is a big one” or “Oh, that is a good one.” It’s useless information. It’s like some fishermen I’ve encountered on the shoreline who will never tell you what they use, or how to use something new.

FRED TRZASKOWSKI LANGLEY, B.C.The editors reply: We’re sorry to learn about your frustration. We thought the writer’s instructions on how to tie hopperdropper and tandem streamer rigs were clear: “I now make all my double-fly rigs

in the same, straightforward way. I tie the main fly to a shortish leader of eight- or 10-pound mono that’s rarely longer than seven feet. Then I tie a two- to four-foot length of lighter mono to the bend of the first hook using an improved clinch knot; this extra section of mono is known as a ‘dropper.’ Finally, I tie the second fly to the dropper using a loop knot so it swims with a little more action.”

I must take exception to the letter from the fellow from Manitoba, saying cross bow hunting is not a bona fide form of archery (Dispatches, “Crossbow conten tion,” November/December 2022). When I first took up archery several decades ago, I hunted with a compound bow. I practised a lot, and became reasonably proficient. After many years, however, my old shoulder was unable to keep up with the practice needed to maintain my shot. I’ve been using an Excalibur crossbow since then.

Crossbow hunting relies on several of the same disciplines as hunting with tra ditional or compound bows. You need to be within a relatively short range of game to take the shot, for example, and you must have a good understanding of animal anatomy for good shot place ment. You also need to tune your bolts for optimum accuracy. Crossbows allow us older folks to enjoy the extended hunting seasons without making it a point-and-shoot pastime. Thank you, and keep up the good work!

HERMAN BAGUSS PRESCOTT, ONTARIOIn “On guard for the West” (November/ December 2022, Outdoor Canada West), we stated that raffles for Minister’s Special Licence (MSL) tags in Alberta will be managed by individual con servation organizations beginning in 2023. At press time, however, Alberta Environment and Parks, which oversees the MSL program, had yet to announce the process for managing the raffles moving forward. Our suggestion that Wild Sheep Foundation Alberta will be handling the raffle for wild sheep tags, therefore, is incorrect. Our apologies for any confusion.

IN MID-NOVEMBER, I was heartened by a press statement from the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (OFAH) regarding Ontario’s controversial Bill 23. Tabled in late October by Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government, the More Homes Built Faster Act is ostensibly designed to address the province’s housing crunch by speeding up approvals to build new homes. That it certainly does, but it also stands to imperil the environment in the process.

Among its many provisions, Bill 23 would strip local conservation authorities of their oversight powers, allow the sale of conservation lands, and remove protec tions for wetlands, forests and farmland. It would also diminish municipal stan dards for building energy-efficient homes. In effect, the bill would allow for eco-unfriendly development in southern Ontario’s diminishing green spaces.

So, when OFAH issued a statement from executive director Angelo Lombardo calling for a pause on Bill 23, I was in complete agreement. In short, he urged the government to take more time “to do their due diligence and review all relevant evi dence and public comments with the critical analysis and debate that it deserves.” According to the statement, OFAH was also conducting a critical review of the bill,

Less than a week later came the bombshell that Ontario would allow housing on almost 3,000 hectares of the environmentally sensitive Greenbelt straddling the Greater Toronto Area—this after the premier promised that would never happen. Then came news that properties in eight of the 15 areas removed from the Green belt were purchased by developers after Ford first came to power four years ago.

It’s clear the premier is no friend of the environment. He’s closed the office of the Environmental Commissioner, fired the province’s chief scientist and killed Ontar io’s programs to fight climate change. But Bill 23, coupled with opening the Green belt to development, brings us to a whole new level. The legislation is a clear attack on our woods and waters, and it should now be shelved completely—not merely paused. The future of southern Ontario’s wild places demands no less. OC

A long-time multi species bowhunter, Ardrossan, Alberta’s Brad Fenson fre quently travels across North America and the world on his hunting adventures. And over the years, he’s learned a lot about keeping his gear safe while en route. On page 26, he offers tips on how to pick the right bow case for your travels.

When he’s not enjoy ing the outdoors with his young family or his students, Toronto outdoor ed teacher Craig Mitchell is often planning his next hunting adven ture, or indulging his passion for outdoor history. In “Gangster getaway” starting on page 54, he digs into the curious criminal past of Ontario’s Lake Erie Fishing Club.

A former commeri cal fisherman, Saint John, New Bruns wick’s Zac Kurylyk now works full-time as a freelancer writer. In this issue’s “Hom age” (page 66), the ardent angler, hunter and motocycle rider shares his thoughts on an iconic piece of outdoor apparel for cold-weather pursuits—the darkgreen woolly pully.

In this issue’s “Fair Game” guest opinion column (page 22), Vancouver Island freelance writer Ryan Stuart argues why it’s time to rethink how salmon hatcheries are run on the Pacific coast. An avid angler and pad dler, his articles have appeared in various outdoor publications, including Outside and and Ski Canada

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF & BRAND MANAGER PATRICK WALSH

MANAGING EDITOR Bob Sexton

ASSOCIATE EDITOR & WEB EDITOR Scott Gardner

ART DIRECTOR Sandra Cheung

FISHING EDITOR Gord Pyzer

HUNTING EDITOR Ken Bailey

PUBLISHER MARK YELIC

MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller

DIRECTOR OF RETAIL MARKETING Craig Sweetman

AD TRAFFIC COORDINATOR Michaela Ludwig

DIGITAL COORDINATORS Lauren Novak and Blaine Willick

CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE: Marissa Miller and Lauren Novak

CONTROLLER Anthea Williams

OUTDOOR CANADA IS PUBLISHED BY OUTDOOR GROUP MEDIA LTD.

Outdoor Canada magazine (ISSN 0315-0542) is published six times a year by Outdoor Group Media Ltd.: Fishing Special, May/June, July/August, Hunting Special, November/December, January/February. Printed in Canada by TC Transcontinental.

SUBSCRIPTION RATES: Canada, one year (six issues), $24.95 plus tax. U.S., one year, $39.95. Foreign, one year, $69.95. Send name, address and cheque or money order to: Outdoor Canada 802-1166 Alberni St., Vancouver, B.C. V6E 3Z3.

MAIL PREFERENCE: Occasionally, we make our subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose products and services may be of interest to our readers. If you want your name removed, contact us via the subscripton contact below.

Publication Mail Agreement No. 42925023. Send address corrections and return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Outdoor Canada, 802-1166 Alberni St., Vancouver, B.C. V6E 3Z3

USPS #014-581. U.S. Office of publication, 4600 Witmer Industrial Estates, Unit #4, Niagara Falls, N.Y .14305. U.S. Periodicals Postage paid at Niagara Falls, N.Y. Postmaster: Send address changes to Outdoor Canada, P.O. Box 1054, Niagara Falls, N.Y. 14304-5709. Indexed in Canadian Magazine by Micromedia Ltd.

EDITORIAL SUBMISSIONS: We welcome query letters and e-mails, but assume no responsibility for unsolicited material.

Distributed by Comag Marketing Group. ©2023 Outdoor Canada. All rights reserved. Reproduction of any article, photo or artwork with out written permission of the publisher is strictly forbidden. The publisher assumes no responsibility for unsolicited material.

Subscriptions and customer service 1-800-898-8811

Subscriptions e-mail service@outdoorcanada.ca Customer service website www.outdoorcanada.ca/subscribe

Outdoor Canada 802-1166 Alberni St., Vancouver, B.C. V6E 3Z3 General inquiries (604) 428-0259

Editorial e-mail editorial@outdoorcanada.ca

Members of the Manitoba Wildlife Federation, Saskatchewan Wildlife Federation and Alberta Fish & Game Association must contact their respective organizations regarding subscriptions.

RETAIL AND CLASSIFIED ACCOUNT MANAGER Chris HolmesNow that’s a happy meal. A mature bull moose appears to crack a smile as he munches on twigs in the wilds of central Ontar io last winter. An adult moose can eat an impressive 20 kilograms of browse in a single a day.

BY MARK RAYCROFT

BY MARK RAYCROFT

Anniversary this year of Ducks Unlimited Canada, established in 1938 to con serve, restore and manage waterfowl habitat. Headquartered at Manitoba’s Oak Hammock Marsh, DUC launched one year after its U.S. counterpart.

Spawning Pacific salmon threatened by debris from a massive landslide this past September on northern B.C.’s Ecstall River, a tributary of the famed Skeena River. Any eggs already laid at the time of the slide were also threatened.

Length in inches of a rare muskie caught in Toronto Harbour this past October by fishing guide Will Sampson. In more than 30 years of environmental monitoring, muskies had never been caught along Toronto’s waterfront.

Weight in pounds of a smallmouth bass caught by Ohio angler Gregg Gal lagher on the Canadian side of Lake Erie this past November. The biggest smallie ever recorded on Erie, once certified it also stands to best Ontario’s 9.84-pound record, caught by Andy Anderson on Birchbark Lake in 1954.

—Red Deer-Lacombe, Alberta, MP Blaine Calkins vows to make good on

October appointment to the Official Opposition shadow cabinet as Shadow Minister for Hunting, Angling and Con servation. The portfolio is one of several new positions Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre created in unveiling his 51-member team of front benchers.

“I will ensure that conservation and our heritage sports are always considered in every decision.”

his

BY STEPHAN LUKACIC

BY STEPHAN LUKACIC

AWILD EDIBLE known as chaga is all the rage right now in the health-food industry, but why all the hype? Namely, modern science is beginning to prove what aboriginal cultures around the northern hemisphere have known for ages: that consuming this weird black mushroom can have a remarkable range of health benefits. I’m living proof of it—chaga tea is the main anti-inflammatory med icine I use to keep my degenerative arthritis in check. It’s also the most antioxidant rich food on the planet, complete with anti-viral and adaptogenic properties among its wide-ranging biological benefits.

IDENTIFICATION Chaga’s scientific name is Inonotus obliquus. It’s a parasitic fungus that’s harvested exclusively off living birch trees, ideally during the win ter months when both the fungus and the host tree are dormant; I often collect chaga while hunting for snowshoe hares or hiking into backwoods lakes to ice fish. To identify this fungus, there are two main things to look for: an outer black crust resembling charcoal, and a yellowish-brown cork-like interior. A good trick to con firm its identity is to dig a small hole into it with a knife to check for the cork-like interior before harvesting.

SUSTAINABLE HARVEST Owing to its new-found popularity, chaga has become extremely susceptible to overharvesting. Only harvest chaga the size of a large grapefruit or bigger, and leave behind a third of its mass. This extremely slow-grow ing fungus takes decades to reach maturity, but it’s capable of regenerating if it’s not entirely removed. You’re also far less likely to damage the tree if you don’t remove the entire growth. For the safest and cleanest results, use a saw.

PREPARATION Chaga is best consumed via hot water extraction, or tea. While ground powder is the most common commercially available product, I prefer processing chaga into roughly half-inch chunks that can be reused many times by simply adding more water to the pot. A small handful of chunks in a saucepan or slow-cooker can be used for days. When making chaga tea, it should never be boiled. Some of its beneficial compounds can be destroyed with too much heat, so a long, slow simmer is best. It takes a minimum of one hour on low heat to start extracting the medicinal goodness, and some studies suggest optimal steeping time is six to eight hours or more. Finally, as with any herbal supplement, consult your doctor before consuming chaga, especially if you have a liver ailment or blood disor der, or you’re using blood thinners or insulin. Otherwise, enjoy the earthy bitter taste, complete with a hint of vanilla! OC

When it comes to catching wintertime splake, the biggest challenge is determin ing whether they’re taking after their brook trout fathers or their laker mothers. If behaving like brookies, splake tend to use shallow shoreline structure and cover. When they’re acting like lakers, however, you’ll find them out much deeper. With this in mind, I always look for a long, finger-like underwater point that offers both shallowand deep-water options. I’ll then drill a few holes in five feet of water near shore (especially around fallen trees), a few in the mid-depths, and more out where the point comes to a tip. To help me quickly figure out where the fish are set up, I’ll then systematically move from hole to hole every 15 minutes or so, changing the location of my set line in the process.

—GORD PYZER

—GORD PYZER

The peak walleye bite on almost every lake takes place a half-hour before sunset, when the amount of light changes the most dramatically. Not that you can’t catch numbers of nice walleye throughout the day, however—provided you target depths matching the twilight conditions they pre fer. When the layer of ice and snow is thin and the weather is sunny, you’ll typically find the fish in 30-plus feet of water. With thicker ice and deeper snow, however, you’ll find the same walleye as shallow as 15 to 18 feet during the day. The options are near limitless, so you need to take the variables into account daily and drill your holes accordingly. —GORD

PYZERWE ENJOY SEEING pictures of your fishing and hunting accomplish ments—and learning the stories behind them. Please e-mail us your images, along with any relevant details (who, what, where and when), and we’ll post them on Instagram and publish our favourites here.

The third time’s a charm. On his third turkey hunt this past spring, Odessa, On tario’s Dave MacIntosh successfully called in and shot this giant gobbler northwest of Sharbot Lake. The 25-pound tom was Dave’s first-ever turkey, so he’s certainly set the bar high for himself.

North Bay, Ontario’s Desmond Nichol was fishing with his son and brother on Lake Temagami in October 2021 when he boated this mon ster 32-inch wall eye, complete with a burbot in its maw. It was one of three walleye topping 30 inches Desmond caught that day, and as a bonus, he’d just learned his recent cancer treatment was a success.

Katie Weeks has hunted for whitetails, moose and grouse, and as of this fall, the 21-year-old from Black falds Alberta, can add ducks to her repertoire. Hunting with her fiancé, Jordan Maltais, and a guide out of Bittern Lake Lodge, they knocked down 24 ducks on her first outing. Up next on her hunting wish list? A cougar.

In her first-ever hunt this past September, 12-yearold Isabella Hannah of Strathmore, Alberta, took this beauty mule deer with her compound bow near Delia. “I released the arrow at 38 yards and hit him perfectly behind the shoulder,” she says, noting how she spotted the deer lying in a field before stalking up to it with her dad, Mike. OC

HARDWATER ANGLERS HAVE often gussied up their ice huts, but Innisfil, Ontario, on the western shores of Lake Simcoe has truly taken things up a notch. Last winter, the town and the Innisfil ideaLAB & Library partnered with outfitter Gail’s Hot Box Huts to transform 11 ice huts into an innovative public art installation.

Each painted by different local artists, the colourful huts were put on display in various public spaces around town throughout last winter, as well as out on the ice itself. A panel of local jurors comprised of representatives from the Innisfil Arts, Culture and Heritage Council, the Barrie Area Native Advisory Circle, and UpLift Black selected the participating artists. At press time, plans were underway to continue with the project this winter, with five additional huts.

“It was to lift our community’s spirits during the long winter months, promote local tourism and encourage a family-friendly Canadian pastime,” says Wendy Ricciardi, the communication coordinator for the Innisfil ideaLAB & Library. “This project also helped us address issues of social isolation, belonging, mental health and well-being in a post-pandemic environment.”

According to Ricciardi, the unique display provided opportunities for local artists, as well, while serving “to connect citizens to their community and their shared history.” The ice huts also support Innisfil’s Culture Master Plan. Last

year, the federal government’s Healthy Communities Initiative funded the proj ect; this year, it will receive support from the County of Simcoe 2022 Tourism, Culture and Sport Enhancement Fund.

Throughout this winter, the five new painted huts will form an outdoor art gallery in Innisfil Beach Park in town, while last year’s 11 colourful huts will be placed out on frozen Lake Simcoe alongside the other rental units from Gail’s Hot Box Huts. OC

BY BOB SEXTON

BY BOB SEXTON

AMONG HIS DUTIES as vice chief of Montreal Lake Cree Nation, Dean Hen derson manages his central Saskatchewan community’s sports, culture and recreation programs. In that role, the 46-year-old helps organize one of the West’s biggest ice-fishing tournaments—the Montreal Lake Walleye Derby, which boasts an impressive grand prize of $100,000. Celebrating its 15th anniversary this March, the derby attracts more than 2,000 anglers a year from across the Prairie provinces, Ontario and bordering states.

While Henderson himself doesn’t compete in the derby to avoid a conflict of inter est, he is otherwise an avid and regular ice angler. “I live two minutes away from the lake,” he says, “so you’ll find me out there after work, probably three or four times a week.” As with the derby competitors, Henderson focuses mainly on Mon treal Lake’s walleye, making him a great resource for advice on how best to target winter ’eyes.

CONDITIONS Henderson says the prime times to fish for walleye are from sunrise to about 11 a.m., then from around 3 p.m. until dark. He doesn’t think the walleye bite is affected much by either sunny or cloudy skies, but he does believe baromet ric pressure plays a role. “Some days, the pressure is high in the morning, but then starts dwindling down for the afternoon,” he says. “I notice that’s often when the fish start biting.”

TACKLE As someone who grew up using line wrapped around a stick to ice fish, Henderson says he isn’t fussy about the kind of rod and reel he uses now. He is par ticular, however, when it comes to line, favouring 15- to 20- pound-test PowerPro braid. And his go-to lure is a Mepps Syclops in Hot Orange, dressed with a walleye eyeball. Although that dressing isn’t permitted during the derby, he says, it’s other wise always effective on Montreal Lake.

TECHNIQUE The key to vertically jigging spoons for walleye is to impart continu ous but subtle action, Henderson says. “You’re constantly moving the lure, not just up and down, but wiggling it around six inches off the bottom.”

PERSISTENCE If you don’t get a hit within 15 minutes, it’s time to move, Hender son says. It’s all about finding the fish, he says, which could mean a lot of runningand-gunning. “You can’t just go to one spot, set up and expect to catch walleye. You’ve got to move around. A lot of times, I’m drill ing a couple of hundred holes a day.” OC

Accidents and health problems hap pen, making it inevitable your faithful canine companion will periodically need veterinarian care. If the idea of four-figure fees scares you, you may want to get pet insurance—with a monthly payment covering the unexpected, you won’t have to choose between your dog and your wallet. Not all plans are created equal, though. Here’s what to consider when deciding if pet insurance is right for you.

OPTIONS There are three main categories of pet insurance coverage: accident-only; accident and illness; and wellness. For working dogs, accident coverage is essential, as it includes injuries such as cuts, broken bones, eye trauma, torn liga ments and poisoning. Accident and illness insurance covers injuries, as well as such things as infections, allergies, arthritis, cancer and parasites. Finally, wellness insurance covers routine visits to the vet, as well as vaccinations, teeth cleaning, blood work, spay/neuter services and other basics. Premiums increase with more coverage and lower deductibles.

EXPECTATIONS Initial out-of-pocket payments are the norm with pet insur ance. Before selecting a policy, therefore, confirm the turnaround time for claim approvals and payouts, which differs from company to company. Also determine the deductible amount and coverage rate.

RESEARCH If you opt for insurance, purchase it early in your dog’s life, but do your homework. Understanding the policy fine print is very important—it can be costly to think you’re covered for some thing when you’re not. Some policies don’t insure newborn puppies or old dogs, for example, and no policy will cover in curable pre-existing conditions. Also read the insurance company’s reviews. Finally, run the numbers, weighing the premiums against deductibles, coverage amounts, payment limits and wait times. For some, costs may outweigh the benefits; for oth ers, the peace of mind will be priceless.

—LOWELL STRAUSS BY ANGELO VIOLA & PETE BOWMAN

BY ANGELO VIOLA & PETE BOWMAN

TO MANY ANGLERS, the N.W.T.’s Great Slave Lake is the best waterbody in the world when it comes to lake trout fishing. That’s a huge claim, considering it competes directly with not-so-distant Great Bear Lake, as well as an array of other Far North laker meccas. Backing it up, though, is the sheer immensity of Slave—it’s the second-largest lake in the N.W.T., the deepest lake in North Amer ica at 614 metres and the 10th largest lake in the world by area, covering 27,200 square kilometres. And at its longest and widest points, Slave measures 469 kilome tres by 203 kilometres, amounting to one massive, trout-filled body of water.

While pike, Arctic grayling and whitefish also inhabit Great Slave, lakers remain the most popular with visiting anglers, followed by the voracious northerns. Head off in any direction, and it seems you’ll find the trout. Indeed, if you were to bring a box of large spoons and simply cast or troll them randomly, you’d head home with some amazing fish stories. The lakers come in all sizes, too, from the constant biters in the five- to eight-pound range, all the way up to 30 pounds or more.

Of course, there are some specific trophy areas of the lake, and the various fishing lodges all have their own time-honoured hot spots. Just be sure to listen closely to the advice from the professional guides. Slave is where we learned that bigger is better when it comes to spoons—as well crankbaits, minnowbaits and even softplastics—for catching giant lakers. We’ve since used that same approach on every body of water similar to Great Slave. It’s a proven formula.

Although it’s been a long time since we’ve visited this beast of a lake, the memo ries remain strong—just ask Ang’s brother, Reno (pictured above). If you’re looking for the fishing trip of a lifetime, along with the lake trout of a lifetime, Great Slave Lake is an absolute must-visit destination. OC

Located 288 kilo metres northeast of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Deschambault Lake is a walleye and pike paradise. Most ice anglers use jigs and min nows to catch the walleye, while bigger dead baits attract the pike. Deschambault Lake Resort is open year-round, making it a good base of operations as you explore the area’s many small back lakes by snowmobile. (306) 632-2166; www.dlrfishing.com

—GORD PYZER

—GORD PYZER

Partially surround ed by northern On tario’s Little White River Provincial Park, Wakomata Lake offers ice anglers the chance to catch lake trout, pike, perch and whitefish. Tie on four-inch white tube jigs for the lakers, spoons tipped with minnows for the perch and northerns, and Meegs jigs for the whitefish. Contact Wakomata Lake Cot tages for lakefront accommodations and help getting on the fish. (705) 992-5900; www.wakomatalakecottages.com

—GORD PYZERThe relatively lightly coloured fur of southern Alberta’s coyotes makes them a favourite in the fur trade, but hunting these wily canines requires patience and persistence. Most successful hunters use electronic calls and decoys to bring coyotes into range, where they’re taken with flat-shooting, small-calibre centrefire rifles. Contact the Alberta Professional Outfitters Society for info on guided hunts. (780) 414-0249; www.apos.ab.ca

KEN BAILEY

DESTINATION

KEN BAILEY

DESTINATION

Colchester, Ontario’s North 42 Degrees Estate Winery offers an enticing pinot noir that pairs nicely with trout, as well as peach and ginger. Expect soft tannins, along with a delightfully fruity taste of cherry and raspberry. You’ll want to serve this red slightly chilled.

SPICY HEAT AND a touch of sweet go together like beer and pretzels, and this recipe is a great example of that. Food is always much more inter esting when flavours pop, and savoury trout is terrific anytime, especially on a cold winter’s evening. Serves 2 to 4

1] Preheat oven to 425°F. Prepare salad ingredients and set aside.

2] Place trout skin side up on parch ment paper on a baking sheet, then make shallow, one-inch-long cuts in the skin to prevent the fillets from curling. Lay lemon slices on top, then the butter slices and a sprinkle of Cajun seasoning.

3] Place trout in oven and bake for approximately 12 minutes. In the meantime, place all salad ingredients in a mixing bowl and toss well. Once the trout is cooked, place the salad on top and serve immediately. OC

• 4 peach halves (canned or fresh), thinly sliced

• 1 cup fresh fennel, thinly sliced

• 1 roasted red pepper, thinly sliced

• ¼ red onion, thinly sliced

• 1 tbsp chopped parsley

• 2 tsp peeled and grated fresh ginger

• 3 tbsp olive oil

• 1 tbsp fresh lemon juice

• Kosher salt and pepper, to taste

• 1 whole trout, filleted with skin on

• 1 lemon, thinly sliced

• ¼ cup sliced salted butter

• 3 tbsp Cajun seasoning

INTRODUCED IN 2021, Browning’s Maxus II maintains many of the elemental features of its predecessor, the now-discontinued Maxus Hunter. At the same time, however, this new autoloader is quite a different shotgun, designed for those who hunt ducks or geese in the foulest of weather and in environs most of us prefer to avoid.

As for the features the enhanced Maxus II shares with the original, foremost is the same tried-and-true Power Drive Gas System, which Browning touts as “the best gas piston design ever.” It sports oversized gas ports to vent gases faster when shooting heavy loads, while the piston’s 20 per cent longer travel stroke improves reliability with lighter loads.

With the original Maxus, the recoil reduction technology was more encomp assing than just the action—the Inflex Technology recoil pad, back-boring and the shotgun’s natural balance also contributed to the 18 per cent less felt recoil and 44 per cent less muzzle jump than other autoloaders. And while the Maxus II has reduced the felt recoil even more, I was glad to see Browning didn’t mess with the action.

The new Maxus also continues to incorporate the Lightning Trigger, which Browning claims is the “finest fire control system ever offered in an autoloading shotgun.” It also kept the Speed Load Plus feature, which directly chambers the first shell loaded in the magazine. And finally, the Maxus II still offers an adjustable stock for fine-tuning the length of pull, drop and cast.

So, what are the upgrades? Most of them serve to enhance the shotgun’s userfriendliness, starting with three improvements that I found handy when wearing gloves: an oversized bolt release, oversized bolt handle and ramped trigger guard for easier loading.

The more predominant changes, however, are to the composite stock. While it still has a camo hydrographic dipped finish, the Dura-Touch finish has been replaced with rubber over-mouldings in key areas, including the forearm and pistol grip. Browning also added a SoftFlex Cheek Pad and a 1½-inch-thick Inflex Recoil Pad, which help take additional sting out of felt recoil, as noted earlier. As well, the redesigned stock is now sleeker for a quicker swing and speedier target acquisition.

My test Maxus II in Mossy Oak Shadow Grass Habitat tipped the scale at seven pounds four ounces—a weight that, when combined with a slight forward muz

zle balance, provided for an easy and smooth swing. The sleeker profile also offered a quicker-handling gun than some of the other waterfowl autoloaders I’ve used, making it ideal in a blind.

All and all, the gun was easier to use than the original Maxus, particularly in tough conditions. I particularly liked the rubber over-moulded additions to the forearm and pistol grip. There’s no ques tion they provided a firm grip, adding to the II’s overall handleability on those nasty days when you might otherwise stay at home in front of the fireplace than sit in a goose blind.

On the trap range, the Maxus II proved to be utterly deadly, powder ing most of 50 clays. It ate and spat out Winchester 118-ounce AA target loads without a glitch, affirming its advertised ability to handle light target loads.

I also patterned four premium water fowl loads from Browning, Federal, Rem ington and Winchester. At 40 yards, I assessed both the pattern density and distribution of 1¼ ounce #2 steel shot, a load I consider about ideal for most goose-hunting situations. With 20 hits in a 10-inch circle, Winchester’s Blind Side had the best overall pellet den sity and distribution. Both Browning’s Wicked Blend and Federal Premium’s Black Cloud were only a tad less effec tive, with 17 and 16 hits, respectively.

In practical terms, you don’t need 20 hits to bring down a goose. The more pellets you can put on target the better, however, as it takes a great wing shot to deliver a central pattern hit on each and every shot—and unfortunately, most of us do not fall into that category.

In the final analysis, Browning’s new Maxus II waterfowl guns are a definite improvement over their original Maxus predecessors. OC

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• Drop at heel: 2″

• Magazine capacity: 4 x 2¾″

WE CANADIANS ARE a hardy lot, but some times winter weather gets so nasty even we don’t want to venture outside. And when that happens, there’s only one thing to do—bring the outdoors in. How so? Thanks to an abundance of great outdoor literature, you can still get your fishing and hunting fix, as the follow ing books reveal.

READING THE WATER ($34.95)

Greystone Books, www.greystonebooks.com Details: By Mark Hume; in teaching his daugh ters to fly fish, the B.C. author reflects on father hood and his lifelong passion for fishing. The promise: “A meditation on finding faith in a deep connection with the natural world.”

FLYING TO EXTREMES ($24.95)

Hancock House, www.hancockhouse.com

Details: By Dominique Prinet; the author relives tales of derring-do from his career as a bush pilot in the Cana dian Arctic. The promise: “Recounts perhaps some of the best northern adventures ever told.”

MAULED ($25)

Rocky Mountain Books, www.rmbooks.com

Details: By Crosbie Cotton and Jeremy Evans; the au thors detail how Evans es caped a near-fatal grizzly bear attack while hunting in the Alberta wilderness. The promise: “An inspiring true-life survival story.”

TROUT TRACKS ($25)

Rocky Mountain Books, www.rmbooks.com

Details: By Jim McLennan; essays celebrating personali ties, wild places and memorable catches from the world of fly fishing. The promise: “Drawn from 55 years of ex cessive obsession with trout, water, streams and flies.”

I NEVER MET A RATTLE SNAKE I DIDN’T LIKE ($24.95)

Thistledown Press, www.thistledownpress.com

Details: By David Carpenter; the Saskatchewan author recounts his encounters with dangerous wildlife, and the lessons he learned in the pro cess. The promise: “Our place in the wild, and the value of the wild in our lives.”

THE LAST GUIDE ($29.95)

Ottawa Press and Publishing, www.ottawapressandpublishing.com

Details: By Ron Corbett; chronicles the life of legendary Frank Kuiack, Algon quin Park, Ontario’s last full-time fishing guide. The promise: “Richly anecdotal, entertaining, and with marvelous pho tographs throughout.”

WINGS OVER WATER ($38.99)

Flashpoint Books, www.flashpointbooks.com Details: Companion book to the like-named IMAX film, featuring 300-plus photos and essays on waterfowl conservation. The promise: “Celebrates the prairie wet lands of North America and the birds that live and breed in this critical habitat.”

This line of comfortable, ultralightweight base layers includes head and neck warmers, long-sleeve tops and long johns/leggings in sizes for men, women and kids ($24.00 to $54.99). Featuring a blend of acrylic, cotton and stretchy elastane, the garments prom ise to retain body heat, wick moisture and prevent odours. Heat Ultra, 1-800-463-1483; www.heatultra.com

Designed for ease of motion when drawing a bow or swing ing a shotgun, this lightweight, water-repellent jacket (US$212 to US$228) features moisture-wicking 37.5-DownTek insula tion, making it suitable as either outwear or a mid-layer. It comes in five men’s and women’s sizes, as well as several camo and colour op tions. First Lite, (208) 806-0066; www.firstlite.com

ALONE IN THE GREAT UNKNOWN ($26.95) Harbour Publishing, www.harbourpublishing.com

Details: By Caroll Simpson; the widowed author’s memoir of single-handedly running an offgrid lodge in B.C. The promise: “Inspiring story of how an urban woman came to own and operate a remote fishing lodge.”

THE WILDEST HUNT ($24.95)

Harbour Publishing, www.harbourpublishing.com

Details: By Randy Nelson; North American conservation officers share their strangest, funniest and most frightening encounters with poachers. The promise: “A thrilling look into a dangerous industry.” OC

This rugged, batterypowered heating blanket (US$599.99) is made for long sits in the frosty outdoors. Measuring six feet by five feet, the weather-resistant blanket heats up in five minutes, providing warmth for threeplus hours. It comes with a rechargeable battery, extension cord, carrying case and chargers. Life Giving Warmth, (805) 222-3257; www.lifegivingwarmth.com

With a removable wool blend liner and a grippy rubber base for traction on ice, Baffin’s waterproof and breathable Yukon boots ($225) are made for “adventurous pursuits in extreme cold temperatures.” The made-in-Canada boots also sport a stylish leather upper, complete with a pull loop for easy entry. Baffin, 1-800-387-5858; www.baffin.com

ON PAPER, SALMON hatcheries make sense: release more baby fish into the wild, and more adult fish will return to spawn. B.C.’s 150-year history of Pacific salmon hatcheries suggests this just isn’t the case, however. No salmon runs have ever recovered to historic numbers owing to hatcheries. So observes B.C. MLA Fin Donnelly, the parliamentary secretary for Fisheries and Aquaculture. “The science shows, in the past we’ve relied too much on salmon hatcheries as the solution to salmon’s problems,” he notes.

After a decade of declining returns (and another disappointing year for anglers on B.C. rivers), it’s time to rethink how we run our hatcheries on the Pacific coast. Right now, hatcheries are simply wasting precious money to produce fewer and fewer salmon. That doesn’t mean they’re a total failure, though. Hatcheries help sustain beleaguered salmon runs and create fishing opportunities, with all the sub sequent economic and cultural benefits. But they don’t create more fish, especially in the long term.

Hatcheries are good at producing more fry, but those fish are less likely to return to spawn than wild fry. And when they do return, some inevitably pollute the gene pool by spawning with wild salmon. Studies also show wild salmon fry from two wild parents are more likely to survive and return to spawn than fry from a hatchery-raised parent.

Meanwhile, research from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and salmon hatchery expert Greg Ruggerone shows that in years with especially abundant pink salmon numbers in the open ocean—the majority of which are hatchery-raised in Alaskan waters—lower numbers of other species return to spawn across the east ern Pacific. They also weigh less, and spawning success declines.

“Climate change has reduced the quality and quantity of the food for fish in the open ocean,” observes Aaron Hill, executive director of Watershed Watch Salmon Society, a charity focused on restoring B.C.’s wild salmon. “So the idea of releas ing more hatchery fish is like letting more cattle out into a field with less grass and thinking you’re going to get more and fatter cows.”

Currently, the B.C Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund and the federal Pacific Salmon Strategy have earmarked nearly $800 million to recover salmon populations. That won’t address ocean survival, however, or curb industrial-scale salmon hatchery programs in Alaska, Russia and Japan. But the funding could

make three crucial improvements to Canada’s hatchery system.

First, the best science possible could be applied to hatcheries. One of the rare good news stories for B.C. salmon, for example, comes from the Okanagan Nation Alliance’s hatchery in West bank, B.C. Rather than look to Fisher ies and Oceans Canada for guidance, the Indigenous-run hatchery turned to Washington State, where a series of lawsuits and subsequent reforms in the early 2000s pushed hatcheries there to adopt better science and become more innovative. The difference has been dramatic, with an estimated 530,000 sockeye returning to the Okanagan watershed in 2022, more than double 2020’s returns and up dramatically from a low of 2,500 in the 1990s.

Next, Canadian hatcheries could invest in the equipment and staffing needed to clip the adipose fin on every single released fish. Right now, only 10 per cent or so are marked, says Owen Bird, executive director of the Sport Fishing Institute of B.C. If every fish were clipped, however, researchers and anglers would be able to better differ entiate between wild and hatchery fish, leading to improved research and fish ing opportunities.

Finally, we need more investment in innovative ideas, such as the Okana gan Nation Alliance’s “hatchery in a box.” A shipping container converted into a small-scale, portable hatchery, it’s designed to boost a salmon run for one or two generations before it’s moved to another stream. First Nations across the province are now using the concept to recover culturally important salmon runs, although its biggest con tribution may be in changing mindsets.

Namely, a hatchery in a box costs $100,000 to set up and thousands to run each year, while a traditional hatchery costs millions to build and millions more to run. “When you build a major facility, you’re invested in it,” says Howie Wright, the fisher ies program manager for the Okana gan Nation Alliance. “You want to keep running it.” And science has shown that’s not in the best interest of salmon—or anglers. OC

You may also submit original prints, slides or discs or thumb drives with high-resolution images to Outdoor Canada Photo Contest, 9 Billings Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M4L 2S1. Please specify the category you are entering, and include your name, address, phone number and when and where the photograph was taken.

THERE’S A REASON New York Yankees slugger Aaron Judge bats first. His onbase plus slugging percentage is outrageous. This past season, he secured his place in baseball history by hitting 62 home runs and breaking Roger Maris’ 61-year-old, single-season home run record in the American League. And if you’re the opposing team manager and think you can get away with intentionally walking Judge, you still have to deal with Anthony Rizzo, Oswaldo Cabrera and Giancarlo Stanton, the second, third and cleanup hitters, respectively.

I like to compare ice-fishing lures for lake trout to the Yankees lineup. For years, a four-inch white tube stuffed with a quarter- to 38-ounce jig has been the lead-off bat ter for most anglers. But what’s on deck if the tube strikes out? For me, it’s a spoon, swimbait and lipless crankbait.

Spoons are the ultimate flash baits because they reflect even the smallest amount of sunlight, imitating the scales of the ciscoes, smelt and shiners that lake trout devour. They excel on massive waterbodies where you can often entice trout from a long distance, with a modest two- to four-inch spoon usually attracting more lakers than a larger one. I suspect it’s a match-thehatch proposition.

I prefer heavier spoons, but whatever weight you use, remember that these lures elicit unpredictable responses. When you spot a lake trout on your sonar streaking after your spoon, it’s sometimes more effective to reel it away quickly, as though the lure were a fleeing baitfish. Other times, letting the spoon fall and flutter works best, while still other times, pausing and keeping it motionless is the key.

My single most memorable day on the ice, for example, occurred many years ago on Lake Superior. I was snapping up a half gold/half silver Williams Ice Jig (pictured), then pausing before letting it flutter back down and pausing again. I couldn’t interest the trout into hitting it, however, until I let it hang dead still in the middle of the water column instead. I can’t tell you how many trout I’ve since caught doing just that.

With swimbaits, meanwhile, I’ve had stunning success with a

three- to six-inch paddletail on a 2 7- or 3 7-ounce Nishine Smelthead. I just drop the bait to the bottom, then retrieve it at a leisurely pace. When a lake trout appears out of nowhere on your sonar and closes in on the swimbait, the key is to not stop your retrieve. Instead, maintain the same speed, let the trout overtake the lure, and hold on.

If you want to make your swim baits even more effective, drop them into a pot of gently boiling water for 20 seconds, then dunk them in ice water. This will straighten out any kinks, making the bait run absolutely true, dramatically wagging its tail and swaying its belly more. And if I’m using a hollow belly swimbait, such as the Basstrix model (pictured), I fill it with scent so that a trailing laker will be convinced it’s real.

Over the past few years, lipless crank baits have become more popular as they’ve gotten slimmer, sleeker and more vibrant. When ciscoes and shiners dominate the forage base, I find the Nishine Simcoe 75 in the ghost shad pattern (pictured) is in a class of its own. When lakers cruise shallow structures in Shield lakes at sunset, meanwhile, the perch hue is killer. The trout will gobble up the hapless perch imitations like so many pistachio nuts spilled on the kitchen table.

The funny thing about lipless crank baits, though, is that lakers are either on them or they aren’t—there never seems to be a happy medium. One day last winter, for example, I crushed a buddy who was fishing with me by icing a trio of 15-pound trout in less than 90 minutes using lipless cranks. Over the next two days, however, I couldn’t buy a bite with the same lures. I’m certain it was the dreary cloud cover the first day that made the trout active, with the vibrating crank capturing their attention. When it turned sunny and bright the next two days, however, the vibration was apparently too much. The key here is deciding when best to put lipless cranks into your lineup.

Batter up! OC

ON PAGE 28, ALSO SEE FISHING EDITOR GORD PYZER’S HARDWATER PIKE TIPS.

IN THE EARLY 1970s, a small Toronto sportwear firm developed an automated way to stuff coats with natural down feathers. The company soon changed its name to Canada Goose, and for three decades quietly produced high-quality par kas for people who work outside during our harsh northern winters. Then about 15 years ago, those same parkas suddenly began appearing on the streets of the world’s trendiest fashion districts. Within a few years, they became a virtual uniform among the coolest young urbanites, even in places that rarely see snow.

The Canada Goose example is one of those rare instances where the whims of fashion accidently settle on something practical and highly functional, then elevate it to mass popularity. That’s pretty much the story of parachute flies, which have gone from a novelty item to a must-have in just a few short years.

Classic dry flies have a hackle feather wrapped around the hook shank; the feather’s barbules stick out horizontally, helping the fly float on top of the water, similar to an aquatic insect. With parachute flies, the hackle feather is wrapped horizontally around a single sturdy wing instead. This is a style of fly, rather than a specific pat tern, so many traditional dry flies can be tied in parachute form. The name “para chute” comes from the idea the horizontal hackle causes the fly to land more gently on the water.

When I began fly fishing more than 30 years ago, I was vaguely aware of para chute flies, but I never saw one in a shop or in anyone’s fly box. The concept has been around since at least the 1940s, but it was generally considered a pointyheaded exercise in fly design, without much practical value. That was partly because parachute flies were very tricky to tie. Also, the idea that they land more gently is questionable, given that dry flies are virtually weightless to begin with. All of this relegated the parachute concept to the margins.

Then about a decade ago, I was surprised when I began hear ing whispers about parachute

flies among fellow anglers. Almost over night, that whisper became a foghorn. Now the Parachute Adams (pictured) is firmly ranked among North America’s two or three most popular dry flies, and embraced by a generation of anglers. And like those sturdy, down-stuffed Canada Goose parkas, modern para chute flies are the real deal. They catch fish at least as well as traditional dry flies, and usually better.

The key is the fly’s structure, with the horizontal hackle above the body. This floats the fly right in the surface film, exactly like a newly emerged insect at its most vulnerable. This seems to make it more attractive to fish than highfloating dry flies. The parachute fly also always lands in the correct upright pos ture, with the wing invisible to the fish.

The wing can be tied with bright white—or even pink or chartreuse— material, making it easier for the angler to see. And the better you can see a dry fly, the more skillfully you can fish it. Adding to the appeal, improved tying materials and clever new techniques have made parachute flies less diffi cult to tie. They aren’t easy, but they’re manageable for tiers of moderate skill. Alternatively, they’re also inexpensive to buy.

You can use parachute flies wherever and however you’d fish any dry fly. With their visibility making them quite easy to fish, they make excellent search ing patterns—they’re one of my go-to choices on unfamiliar water or when there’s no apparent insect activity. The workhorse sizes are 12 and 14, but it’s handy to also have a few smaller and larger ones.

The grey body and mixed grizzly and brown hackle of the Parachute Adams is a proven fish-catching combo, derived from its popular forebear, the traditional Adams. I like parachute flies in generic cream, tan and black, too.

Imaginative fly tiers have also cre ated lethal, low-floating grasshopper and ant imitations using horizonal hackles. Amazingly, this once-ignored technique has already become yet another tool for fly designers, and I, for one, am excited to see what they come up with next.

OC

WHETHER YOU SHOOT a compound, recurve or crossbow, it only makes sense to protect your expensive gear, and that’s where a bow case can be indis pensable. It’s the first line of defence against damage to a bow’s limbs, cams or string, which are all vital to its operation. A case can also keep your bow clean and free of clutter—grass caught between the cam and string, for example, can cause the rig to derail when drawn. And if you travel with your bow, especially by air, a case is a must-have.

So, what kind of bow case is right for you? The level of protection you need essen tially comes down to if, how and where you plan to transport your bow. For start ers, hard cases are ideal for situations in which you don’t have complete control over your gear, while soft cases are good for protection in the field or during trips to the range. Here’s what else to consider before making your choice.

A buddy once sent me a picture of a baggage handler throwing his bow case toward a luggage cart, only to see it careen off the cart and across the tarmac. Understandably, he was furious about the mishandling, but his bow remained unharmed because it was in a well-protected case—a good example of why an airlineapproved case is so necessary for air travel.

Some hard cases are built like vaults, but there are also lightweight, durable options. Look for pillar supports within the case, which provide extra protection and ensure the case doesn’t get crushed. If you expect to be travelling or hunting a lot by boat, also consider a waterproof hard case that floats.

Even with a hard case, add a layer of clothing in and around the bow for a snug fit and to ensure crucial accessories such as the sight are not compromised; some bow hunters even construct a small cage or box to fit around their sight. International travelers will also need to lock their bow cases; if you’re heading stateside, get a latch approved by the U.S. Transportation Security Administration. And if you plan to be in airports and on the go a lot, get a case with wheels to help ease the burden.

Even with a locked hard case, thor oughly inspect your bow once you arrive at your destination. A hunting buddy of mine once flew to South Africa for a Cape buffalo hunt only to discover someone had dry-fired his bow while

A soft carrying case is mostly suited for trips to the bow shop or range, but it can also work well on trips afield. They’re less bulky than hard cases and easy to strap down on an ATV, yet still provide protection from the elements and imme diate hazards. By otherwise carrying an uncased bow into the backcountry, you risk catching the string or damag ing the limbs on a branch, for example, or getting mud or other debris in the cams. Just know that a soft case is only a frontline of defence, not something you can sit on or handle roughly, as you can with a hard case.

Before making a purchase, determine what and how many accessories you want to fit into the case alongside the bow. Some cases allow you to practi cally bring along a portable archery shop. A good-sized case can provide portable storage for extra arrows or broadheads, slings, releases, wax and a set of Allen keys, keeping everything you need in one place.

Any case is better than no case, but you typically get what you pay for. If a case feels flimsy, it is. And with less expen sive options, there are often problems with the latches and fasteners. It’s best to match the case to your investment in your bow and accessories. You don’t have to spend a fortune, but consider the gear the case will be protecting, and what it would otherwise cost to repair or replace—that will help you put the price into perspective. OC

duced in the sweet spot between the 6.5s and the .300s, including the 27 and 28 Noslers and Winchester’s 6.8 Western. Once again, ballistics sug gest those are fine-performing rounds, but will they stand the test of time? That’s hard to say.

THE 6.5

AS LONG AS there have been hunting camps, there have been campfire debates over which cartridge is best for a particular game animal. These discussions were invariably fueled in part by the opinions of hunting and gun writers, who have never been shy about voicing their opinions. I confess to penning a few of those articles myself over the years. Editors loved them, and readers lapped them up, eager to weigh in with their two cents’ worth.

In writing those articles, I had the opportunity to test many of the newest car tridges of the day—some in hunting scenarios, others on the range—and they all lived up to their billing. But were they better than the cartridges already on the market? Before investing in a rifle chambered in any hot new round, always ask yourself if you think the cartridge will remain relevant over the years to come. The answer won’t necessarily be yes.

Over the past 25 years, we’ve seen a series of different cartridge trends. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, new magnum cartridges, including the short-actions, were all the rage. They became popular very quickly, but 10 years later, most had all but disappeared from the scene. Sure, the .300 Winchester Short Magnum has enjoyed staying power, and the .300 Remington Ultra Mag. still has a small but ardent fol lowing. Most of the others, however, enjoy little popularity today.

There was nothing wrong with any of those cartridges, but several influenc ing factors conspired against their longevity. That included declining interest from the gun- and hunting-related media, as well as rifle and ammunition makers not willing or unable to include them in their production lines. And with many of the magnum cartridges, there was a trade-off many hunters weren’t willing to accept— marginally improved ballistics for increased recoil and a higher price tag.

In 2007, the introduction of Hornady’s 6.5 Creedmoor as a hunting round was a resounding success. It arrived on the scene amid great fanfare, with the outdoor press convincing us it was second only to Thor’s hammer in its ability to smite game at ungodly distances. It was touted as an efficient, light-recoiling round with a high ballistic coefficient that was well-suited for small- and medium-sized game at extended distances—and that was true. But was it really any better than other cartridges already on the market? Again, I’m not so sure, but it did inspire further introductions of 6.5 cartridges, most notably the 6.5 RPC.

Over the last seven or so years, we’ve also seen several new cartridges intro

For all the hype surrounding the many newly introduced cartridges, the fact is they generally perform only marginally better than what’s already out there. Does a 10 per cent increase in velocity or downrange energy really make a meaningful difference? Probably not at the distances most of us shoot our game. That’s especially true in this era of better-than-ever bullets and optics that allow hunters to be more precise than many of us could have imagined a few years ago.

The truth is, old standbys such as the .25-06 Rem., .270 Win., 7mm Rem. Mag., 30-06 and.300 Win. Mag. can do virtually everything the Johnnycome-latelies can. Just take a hard look at the ballistic tables and you’ll see the performance differences are marginal. That considered, it’s dif ficult to say how long some of the newer cartridges will last. The 6.5 Creedmoor has certainly established itself, with most rifle and ammunition manufacturers supporting it. Perhaps some of the others will also stay with us, but only time will tell.

I understand the need for, and the value of, new hunting cartridges. There are definitely hunters who always demand something new and different—I mean, who wants to shoot the same old cartridge their father and grandfather used? Some people also like to be on the cut ting edge of technology, and that’s a good thing; it’s one way to ensure manufacturers aren’t resting on their laurels, and are instead striving to improve their products.

So, I’m all for it—keep those new cartridge introductions coming. It’s good for the hunting industry. If you’re considering buying your next rifle chambered in one of the new offerings, however, just remember that even though something’s the latest, it’s not always the greatest. OC

SEE PAGE 48 FOR HUNTING EDITOR KEN BAILEY’S AFRICA TRAVEL TIPS.

BY GORD PYZER

BY GORD PYZER

I SPEND AS many days fishing on the ice as I do on a boat in open water. Such is the out door life in the Great White North, where I can tiptoe out onto frozen water in mid-November and not put away my auger until mid-April. It’s nothing to spend 75 days each winter drill ing holes and setting lines. And for much of that period, I’m fishing for the biggest preda tors in the lake—giant northern pike. How big? My personal-best so far is a 53-inch beast I caught while filming an episode of In-Fisher man TV with my good friend Doug Stange, the show’s host. The next largest is a 50-incher I tag-teamed with my buddy Bob Izumi while the cameras were rolling for his Real Fishing Show

All that time spent peering down a hole in the ice, and watching for distant tip-up flags to fly, has taught me some important lessons about »

catching these big fish. For starters, I’ve learned that pike are the most misunder stood fish we pursue during winter. But don’t you just look for weedy areas, then set dead baits under tip-ups? Not by a long shot.

“I’ve always said that we know less about what pike do in the winter than any other time of the year,” says my friend and former colleague John Cassel man, now retired as senior research scientist with

Ontario’s Ministry of Natu ral Resources. “It is truly an unknown period of their life cycle. The more we learn about it, the more fascinat ing it becomes.”

I can certainly attest to that. And as Casselman

says, “What pike do in the winter is much more impressive than what they do in the summer.” Here are the other key things I’ve learned over the years to catch more and bigger northerns through the ice.

I always carefully check the weather forecast before deciding which pike lake I’m going to target on any given day, but the reason why may surprise you. It’s not to determine whether I’ll be going fishing—that’s

a given—but rather which lake is likely to produce the best action given the fore casted conditions.

Why is the weather so important? When it comes to triggering fish to feed, Casselman explains, noth ing is more significant than the amount of light stream

ing through the ice and snow into the water below. The more light there is, he says, the more it stimulates a fish’s endocrine system, prodding it to eat.

To prove this point, Casselman used a dim mer switch to regulate the light in the lab where he kept captive pike. When he brightened the lights to between 300 and 700 lux— matching the level of light under the ice on a sunny January day—the fish immediately swam up from the bottom of the tank and became active. Conversely, he put the pike to sleep when he turned the lights down. Apparently, the deci sion to rest, prowl and feed is beyond their control, dic tated almost entirely by the amount of light.

So, if the sun will be shin ing brightly, I always pick a lake where the potential is high to catch the trophy of a lifetime. On the days I caught those giant fish with Stange and Izumi, for example, it was so bright we needed sunglasses to cut the glare. I’ll also choose a bright day to explore a new lake I’ve never fished before. This is especially the case if the lake has dark or stained water, which would other wise make it tough to ice a big pike on a cloudy day. When it’s overcast and the light level is less than ideal, on the other hand, I’ll target clear bodies of water. I figure that the clear water,

especially if there’s minimal ice and snow on the surface, will enhance any light mak ing its way through. On such days, I’ll also fish for fun on shallow, weedy lakes filled with medium-sized pike that can’t escape to deepwater refuges. It’s all about optimizing the

I’ve started catch ing pike the last few years jigging large lipless crank baits, such as the four-inch Kamooki SmartFish Rain bow Trout (pictured above). I thought the tactic would simply attract the fish to my deadbaits, but I was shocked to catch as many pike on the cranks as my set lines. For this presen tation, I use a longer, 42-inch, heavy-action ice rod and reel spooled with 20- to 40-pound Maxima or Sufix 832 braid.

A 30-pound test leader fashioned from AWS Surflon Micro Supreme tieable wire complements the set-up perfectly. Just be sure you’re hang ing on tight when one of these freshwater gators tries to rip the rod out of your hand.

I live on the vast Cana dian Shield, where most of the lakes I fish are heavily structured, with countless boulder-strewn points, rock reefs and granite shoals. In the fall, the pike pull out of the weedy bays and coves where they spent the summer and concentrate around these hard-rock fea tures adjacent to the mainlake basin. I call them “bus stops,” because they remind me of the places kids wait to be picked up when they return to school after the summer holidays. In Octo ber and November, it’s pos sible to catch trophy-sized

pike on consecutive casts at such locations.

Bus stops appeal to north erns in the fall because they’re primary contact spots for whitefish and ciscoes, the high-protein, soft-rayed forage fish the big toothy critters like to eat. The pike will intercept the dense schools that lay their eggs on the rock rubble and stones, and ambush the ones that hang around into winter after spawning.

Why then do so many pike anglers rush into weedy bays to set tip-ups as soon as the lake freezes over? I mean, some of the best pike action of the entire open-water season just took

place at the main-lake bus stops, so why not return to them instead? I do, and the fishing is not only as good, it’s often better than it was before ice up.

What’s even more of a head-scratcher, though, is that those same anglers will frequently tell you they stop fishing for pike in weedy bays during autumn. The cabbage has withered and died, they claim, and the decaying vegetation has sucked the oxygen out of the water. If that were actu ally true—which it isn’t— why then would they rush back to the weeds at first ice? It’s such a counterpro ductive strategy.

Don’t make the mis take of jigging—or suspending your dead baits—too close to bottom and below the fish. Northern pike use structure, cover, available daylight and the underside of the ice to silhouette their prey. They are fine-tuned predators that isolate forage swimming above them, so fishing too high is better than fishing too low.

One of the coolest things I’ve discovered about Shield-lake pike is they will follow and prey upon the whitefish and ciscoes dis persing back out into the main lake. And they’ll inter cept them on the same rock and boulder points, bars, saddles and reefs that we typically target for winter time walleye, sauger and perch. The pike tend to hold a little shallower, so I’ll often hang a dead bait under a tip-up in their pre ferred 10- to 20-foot zone,

while I jig for walleye and perch out deeper on the same structure.

When I’m ice fishing solely for big northerns, on the other hand, I’ll ring the structure with holes within the prime depth zone. I’ll then set a quickstrike-rigged dead bait in one hole, while I jig a 3½-inch Rapala Jigging Rap or Jigging Shadow Rap in a second. I remove the treblehook from the Jig ging Rap—a trick I learned from Stange—because you almost always hook pike

on either the front or back single hook. The treble also tends to snag on the under side of the hole as you try to land the fish. The hugely realistic Jigging Shadow Rap lacks a front hook, however, so I keep its treble attached for insurance, and only auger wide 10-inch holes to minimize snags.

My early- and midwinter Shield-structure strategy is to run-andgun as many main-lake structures as possible over the course of the day. And while it may sound strange,

as soon as I catch a really nice fish, I typically move on. That’s because of some thing else I’ve discovered about these main-lake rock fish—you’ll typically catch only one or two on a struc ture, but they will almost always be big. Most days, in fact, it’s harder to catch a fish weighing less than 10 pounds, with a dispropor tionate number averaging almost twice that size.

According to Casselman, large pike are fiercely ter ritorial and intolerant of other large pike (the excep tion being if they grew from fry together). That’s why you’ll rarely find more than one lunker on the same structure or cover. Indeed, one of my most memorable days of fishing was when I was hosting Stange, who was filming an episode In-Fisherman TV. We put close to 100 kilometres on our snow machines, hop scotching from one mainlake rock reef to another. I forget how many King Kong northerns we hauled in that day, but it was as impressive as the size of the fish. And we never caught more than one pike on any single piece of structure.

SUSPEND A DEAD BAIT IN ONE HOLE AND JIG A JIGGING SHADOW RAP (TOP) OR JIG GING RAP IN THE OTHER

Of course, no discussion about ice fishing for pike would be complete with out getting into the weeds. It’s the place to be when a lake is shallow with no deepwater structures, and devoid of pelagic forage such as whitefish, ciscoes and rainbow smelt. Even in lakes that offer all of those things, however, pike will still crowd into grassy cover at last ice as they stage to spawn. But not just any weeds will do.

“Pike are fussy about the density of the aquatic veg

etation,” says Casselman, pointing to some interest ing Dutch studies on pike and prey behaviour. “If the vegetation was too dense, pike were unable to control a burgeoning prey base. We know, of course, that pike predation involves an edge effect, normally preying out of the edge of weedbeds.”

Out of the 195 pike caught during the Dutch research, more than half were caught in areas with less than 35 per cent weed cover. The conclusion? If the weeds are too thick, you won’t find the pike there.

During his own research in several northeastern Ontario lakes, Casselman

also discovered the den sity of weed growth in a lake strongly influences the population of pike, and their ultimate size. In short, he found you are more likely to catch a trophy-sized pike in a lake or reservoir with plenty of open water and tapering weed edges, than in a lake that resem bles Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp. When it comes to weeds and pike, you can definitely have too much of a good thing.

If I’m ice fishing a jagged weedline, I drill my holes at the tip of weedy points and along inside turns. But if the edge is fairly straight, as is often the case when the grass grows along a contour, I’ll place my tip-ups perpendic ular to the weedline. That way, the pike will run into at least one of my dead baits, no matter how they follow the edge.

There’s no disputing pike go gaga for fresh dead baits such as ciscoes, suckers and smelt (where legal), or even store-bought mackerel and saltwater herring. The best way to present a dead bait is under a tip-up using either a quick-strike rig or a circle hook. You can easily make your own quick-strike rig with 14 to 18 inches of 20- to 30-pound titanium, stainless steel or sevenstrand wire. Simply tie or crimp on two #4 Gamak atsu Round Bend Treble Hooks, spaced 2½ inches apart, to one end of the leader, then add a #4 swivel (or snap) to the other end.

Doug Stange pioneered the use of quick-strike rigs and dead baits for pike in North America more than 30 years ago, learning the fine points from Dutch experts such as Jan Eggers. Doug and I quarrel to this day about whether it’s best to hang your bait horizon tally (my preference) or

and easy live-release. Quick-strike rigs have served me over the years—I can honestly say I’ve never deeply hooked a fish—but using a single barbless 5/0 Gamakatsu circle hook (4/0 for smaller dead baits) has taken the dead-bait game a step further. I attach my circle hook to an 18-inch length of 30-pound AWS Surflon Micro Supreme, a

perfectly straight and not bent or offset to one side or the other. (Also please see www.outdoorcanada.ca/ quickstrikepike.)

What I particularly like about circle hooks is that when you see a flag fly, there’s no rush. If the ice is slick, you can tiptoe out slowly, lift the tip-up out of the hole, grab the line and pull steadily in one direc

around with this rig, you can slide your hand down along the fish’s head and slip your fingers in behind its gill plate to pull it up the hole. Circle hooks are not only better for the fish, they’re clearly better for the angler, too. OC

UH-OH. YOU just pulled your ice-fishing gear out of storage and noticed a few things are missing, and the accessories you still have are, well, a little the worse for wear. Talk about a fantastic excuse to update your hardwater arsenal. To that end, we’ve been survey ing the latest and greatest new offerings for ice anglers, and these are our favourites.

Sporting a minnowshaped pro file and 3-D holographic eyes, this quick-sink ing spoon ($5.49) is designed to impart an erratic action mimick ing a wounded baitfish. It comes in 12 different colours (including UV options for maximum visibility) and 1⁄16- and 1⁄8-ounce sizes. VMC, (905) 571-3001; www.rapala.ca/vmc

This sonar unit ($4,229.99) is packed with features, including the LiveScope Plus Sys tem with both down and forward (up to 200 feet in any direction) livescanning. It also comes with the Echomap UHD 95sv chartplotter, a lithiumion battery, and more. Garmin, 1-866-4299292; www.garmin.ca

Weighing less than 22 pounds, Ion’s latest electric ice auger ($699.99) features the Turbo high-speed cutting system, with a choice of eight- or 10-inch blades. It promises to bore through up to 1,200 inches of ice on a single charge, at 2.2 inches a second.

Ion, 800-345-6007; www.ioniceaugers.com

The lever-locking flipup handle on Jiffy’s latest auger ($119.99) makes for easy storage and carrying. The drill assembly extends up to 24 inches, and uses two shaver blades for fast cutting. It’s avail able with either sixor eight-inch blades.

Jiffy Ice Drills, (920) 467-6167; www.jiffyonice.com

The insulated, light weight two-seat Yukon flip-over (US$999.99) boasts Clam’s new XT side-door system, so anglers don’t have to step over gear or ice sports a clear silicone bill that’s shaped like Mickey Mouse ears to impart a unique wriggling and darting action. It’s available in 15 colours, and a choice of #8, #10

33-inch-long softsided case ($49.99) also has exterior stor age pockets, as well as oversized zippers, carrying handles and a shoulder strap. It comes in sassy grey/

Tough and light weight, Eskimo’s Keeper jacket and bibs (US$249 to $259 each) are designed for ease of movement. Available in men’s and women’s sizes, they have 80 grams of Thinsulate insulation, Uplyft flotation assis tance and numerous zip pockets. Eskimo, 1-800-345-6007; www.geteskimo.com

This handy hardwa ter kit (US$84.99) includes Smith’s RegalRiver four-inch stainless folding fillet knife with a non-slip handle, 6½-inch stainless steel pli ers, a nine-inch jaw spreader, scissors with sheath, line clip pers, and a mesh storage bag. Smith’s, 1-800221-4156; www.smiths products.com

Designed for extra protection from the cold and wet, these lightweight gloves (US$49.99) have a water-repellent softshell outer, a leather-reinforced polyurethane palm and Primaloft insula tion for warmth. They come in sizes small to 2XL. Ice Armor by Clam, 1-800-4233474; www.clam outdoors.com

Along with a lightand wind-blocking outer shell, insulated quilted inner shell and reinforced cor ners, this hub shelter ($829.99) for six to eight anglers features a full door, so there’s no more tripping over a sodden or frozen threshold. Otter Outdoors, 1-877466-8837; www. otteroutdoors.com

Designed for youths, this cheerfully coloured spinning combo ($49.99) has a durable fibreglass rod with stainlesssteel guides, plus a skeleton reel seat and contoured knob for small hands. It comes in 24-inch ultralight, and 26-inch light models 13 Fishing, (905) 571-3001; www. rapala.ca/13-fishing

1|

Preheat oven to 350°F. Combine meatball ingredients in a mixing bowl, then roll into balls (makes approxi mately 20). Place meatballs on a sheet pan and bake for 15 minutes or until well done, then set aside.

2| In a large pot over medium-high heat, add oil and cook carrots, onion, parsnip and garlic until tender.

3| Reduce heat to medium, add tomato paste and lightly caramelize, then add canned tomatoes, stock, beans, kale and cooked meatballs. Cover and reduce heat for 15 minutes.

4|

Add cooked pasta, salt, pepper and basil, then bring back to a boil. Ladle into soup bowls and sprinkle with Parmesan cheese.

• 1 pound ground elk

• 1 whole egg

• ¼ tsp dried thyme leaves

• 1 tsp chopped garlic

• Kosher salt and pepper, to taste

• ½ cup breadcrumbs

• ¼ cup canola oil

• 2 carrots, diced

• 1 onion, diced

• 1 parsnip, diced

• 3 cloves garlic, chopped

• 2 tbsp tomato paste

• 796 ml can whole diced tomatoes

• 750 ml chicken stock