32 minute read

Cycling Japan

SPECTACULAR AUTUMN RIDES

CYCLING JAPAN BY TAKASHI NIWA TRANSLATED BY

Advertisement

SAKAE SUGAWARA

Autumn is Japan’s most colorful season and the best time of year to be outside enjoying some two-wheeled social distancing. We’ve chosen five routes—all easily accessible by car—where you can immerse yourself in autumn’s splendor.

NORIKURA, NAGANO Japan’s Highest Paved Road

The name “Norikura” is sacred to cycling hill climbers in Japan. Tatamidaira Basin (2,720 meters) is the highest place you can reach on paved roads in Japan. Just park your car at the Norikura Kogen highlands and pedal up! It is a 20.5 kilometerroute with an elevation gain of 1,260 meters. No personal motor vehicles are allowed on the route so cyclists have the right of way (taxis and shuttle buses are exceptions). Views from above the treeline are spectacular, but beware of sudden changes in weather and make sure to bring cold weather clothing. Distance: 51 kilometers (round trip from the Norikura Kogen to Tatamidaira) Peak Kōyō: Mid to late-September

Norikura Okudatami

KURIKOMAYAMA, IWATE Tohoku Peak Kōyō

Mt. Kurikoma (Kurikomayama) is one of the top fall foliage spots in Tohoku. From the center of Ichinoseki City, in the south of Iwate, it is a 45-kilometer ride to Kurikomatouge (Kurikoma Pass). We recommend this as a round-trip ride and Ichinoseki is on the the Tohoku Shinkansen (bullet train) Line if you choose to come by train. The route climbs about 1,100 meters and, with this much elevation gain, you will encounter the “true colors” of autumnal leaves as they gradually change colors from the foot of the mountains to the top. If you have extra energy and time, the peak of Mt. Kurikoma is a three and a half-hour hike up and down from the pass. Distance: 90 kilometers (round trip to Kurikoma Pass) Peak Kōyō: Early to mid-October

OKUTADAMI, FUKUSHIMA Deep Forest Foliage

When asked where to see the best fall colors with virgin forests of beech and other deciduous trees, my first answer is always Okutadami. It is recommended to cycle one way through the forests from Hinoemata Village in Fukushima Prefecture to Uonuma City in Niigata Prefecture (Approx. 85 kilometers), but you can enjoy seasonal foliage by making a round trip visit to Numayama-tōge (Numayama Pass) which is about 23 kilometers one way with about 820 meters of elevation gain. Upon your return to Hinoemata— after a chilly downhill—enjoy a heavenly dip in the onsen at one of the many minshuku. Distance: 46 kilometers (round trip from Hinoemata to Numayama-tōge) Peak Kōyō: Mid-October

LAKE KAWAGUCHI, YAMANASHI Fuji Five Lakes Fall Cruising

Kawaguchi-ko is one of the Fuji Five Lakes and boasts a view of colored forests and Mt. Fuji across the lake. A 15-kilometer loop around the lake with a short cut across Kawaguchi-ko Ohashi bridge is almost flat and good for cycling beginners. Depending how much time and energy you have the route may be extended by including Sai-ko or Shoji-ko and Motosu-ko in the loop to make the ride 28 or 62 kilometers respectively. Distance: 15 kilometers Peak Kōyō: Mid-November

KYOTO AND NARA Ancient Temples and Neighborhoods

Kyoto and Nara are simply beautiful in autumn. Grab one of the well market maps of the city and enjoy the colors temple hopping on a 20-kilometer route throughout Kyoto. Pedal further out to the suburbs—Arashiyama on the west, Ohara in the north or Yamashina in the east—and you take in the ancient capital to the fullest. Nara City and its neighboring towns and villages also have many temples and shrines with beautiful autumn flora. Pictured here is the outskirts of Ikaruga, where Horyu-ji temple is located. Idyllic landscapes like this are part of Nara’s charm. Distance: Approximately 20 kilometers Peak Kōyō: Late-November

Lake Kawaguchi

LEGENDS OF THE GENJIRO RIDGE

BY TONY GRANT

For a long time Tsurugidake was regarded as the dwelling place of demons. No place for men. Its razor-sharp ridgelines and sheer cliffs were too difficult, too dangerous. It was literally the last blank spot on the map of Japan, an unknown. That is until 1907, when a rivalry between a military map-making expedition and the Japanese Alpine Club brought about its first ascent. Or so they thought…

Legend has it that when the Japanese Alpine Club arrived at the 2,999-meter summit they found the remains of a spearhead several centuries old. Nobody knows the identity of the lone visionary who braved the valleys of hell to slay those ancient demons and leave this spearhead there at the top of the world.

Of all the iconic alpine variation routes on Mt. Tsurugi, there is something special about the Genjiro Ridge. Viewed from the upper reaches of Tsurugi-sawa it appears impregnable; flanked by sheer walls of rock and vegetation, and rearing up over 1,000 meters from the valley floor directly to the summit, through two gigantic rocky pinnacles. It presents a vision both terrifying and alluring, and viewed from this aspect, the crux of the puzzle appears to be just getting onto it in the first place.

But as is so often the case, those early pioneers of Japanese alpinism were able to root out an ingenious way through, and in July of 1925, the great Kinji Imanishi gifted us one of the most beautiful variation routes in the Japan Alps.

My own adventure on the Genjiro began with a 2:45 a.m. alarm call in the tent at the Tsurugisawa Campground. I always find sleep an elusive luxury the night before these things; and after the previous day’s tortuous approach from Tokyo, involving multiple train connections, the trolley buses and ropeways of the Tateyama Kurobe Alpine Route, and then the slog with heavy packs over the Bessan Col, this night was no exception. At such times a good strong cup of coffee insulates the fragile psyche from the mental construct of what we are about to attempt.

Cinching our harnesses and shouldering backpacks, my climbing partner Riccardo and I set off down the faint trail into the lower reaches of Tsurugi-sawa by the light of our head torches. We soon reached the top of the year-round snowpack, recently classified as a glacier, but opted to stick to the trail hugging the slope above, rather than tangle with the hollow mess of late-summer conditions we could see below us.

After some time, the steep snows of the Heizotani Valley appeared on our left, as the dawn turned the sky salmon pink. It was time to begin the search for the elusive access point to the foot of the Genjiro.

The Japanese topographic maps show two ways of accessing the ridge: the “Ridge Route” and the “Runze Route.” The latter is the way to go in spring snow conditions, when the gully (runze) is full of snow, presenting a steep but straightforward snow slope. In summer conditions it is very difficult, steep and full of loose rock, with some hard climbing and sparse protection; much better to take the ridge route, which offers a wellworn trail, easy to follow. An hour later, having learned this lesson the hard way, we eventually located the ridge route and were off to the races.

This initial climb was unremittingly steep but well featured, and we soon got into a decent flow, punctuated by one short section with in-situ pitons that required the rope. As we began to get above the trees and into the haimatsu (dwarf pine) zone, we encountered one particularly exposed slab that prompted Riccardo to reflect on the limits of his free-soloing comfort zone. Eventually, after several hours of grind, we emerged onto the summit of the first of the Genjiro’s grandiose pinnacles.

The depth of the exposure around us was dizzying, and my eyes were constantly drawn to the ramparts and pinnacles of the famous Yatsumine Ridge, across the open air of the Chōjirodani Valley. Continuing over the pinnacle, a steep down-climb brought us into a narrow and improbable col, with a sheer and uninviting ascent on the other side. As is always the case on this ridge though, what appears improbable from a distance always reveals a path through as you get closer. Picking our way up the nearvertical arête on the other side, we were struck by how much we were enjoying ourselves.

Fr o m t he to p of t he s e co n d pinnacle the for tress of Tsurugi’s s u m m i t r e a r e d i n t o v i e w, a s I approached an in-situ rappel anchor on the cliff edge above the col that connects the second pinnacle to the upper mountain. I arranged the rope, slid down the 30 meters to the col, and then sat down to eat and drink while I waited for Riccardo to make the abseil.

T h e w a y t o t h e s u m m i t w a s now open to us and, mindful of the ever-present chance of afternoon thunderstorms in the Alps in summer, we hustled across to the final ridgeline. The ridge seemed to steepen in reverse correlation to our energy levels, and after what felt like endless scrambling, I glimpsed the summit shrine above me, and climbed out of the void and onto the small perch of Tsurugi’s summit.

Wispy afternoon cloud swirled gently around us as we chatted to a couple of hikers, and arranged our summit photos. The weather looked stable, and the pressure was off, so I indulged in some time to rehydrate and reflect on past experiences there; like the magnificent 12-pitch left arête of the Chinne, just beyond the head of the Yatsumine Ridge.

As the afternoon wore on, we slowly picked our way down the normal “Bessan Ridge" hiking trail, across the infamous “Kani-no-yokobai” traverse, until we arrived at the Kenzansō Hut. Back on relatively flat ground once again we donned our face masks, the new reality of these coronavirus times, and sprawled out on the steps of the

hut to enjoy an ice-cold beer.

It had been a truly wonderful and memorable day with a good friend. And as we sat reminiscing about the Genjiro, I was filled with both gratitude and admiration for Imanishi-san and all of his contemporaries from the Golden Age of Japanese alpinism, and for the body of classic routes they left behind.

OTHER HIKES NEAR MT. TSURUGI

If alpine variation routes are not your thing, there are plenty of other less technical options around the Murodo Plateau. • Enjoy the history and drama of the famous Kurobe Dam, traversing the North Alps on the mind-blowing infrastructure of the Tateyama Kurobe Alpine Route. • Take a relaxing stroll around the hiking trails of Jigokudani, with an onsen at one of the huts. • Tr a v e r s e t h e t h r e e p e a k s o f Tateyama, one of Japan’s three famous holy mountains. • Enjoy the hike up neighboring Mt. Dainichi, with unbeatable views across Toyama Bay. • Spend a night at the Tsurugigozen Hut on the Bessan col, and photograph Mt. Tsurugi at sunset and sunrise. • Challenge your mind and body with an ascent of Mt. Tsurugi by the normal “Bessan Ridge” hiking trail.

10 CLASSIC ALPINE CLIMBS OF JAPAN (VOLUME 2)

If you’ve always wanted to climb a classic alpine route in Japan, but didn’t know where to start, check out Tony’s latest book in the Amazon Store, “10 Classic Alpine Climbs of Japan (Volume 2).” Tony’s newest book is packed with invaluable information for climbing enthusiasts such as: • Full route descriptions, including transportation and access, for some of the best alpine climbs in the country. • Route maps, topos and lots of photos to help with route-finding • Additional essays on Japanese maps and GPS apps, climbing grades in Japan, the climbing seasons here, rescue insurance and much more.

A v a i l a b l e n o w o n A m a z o n at: www.amazon.com/Classic

Alpine-Climbs-Japan-Climb/dp/

B08DSYSRHM. v

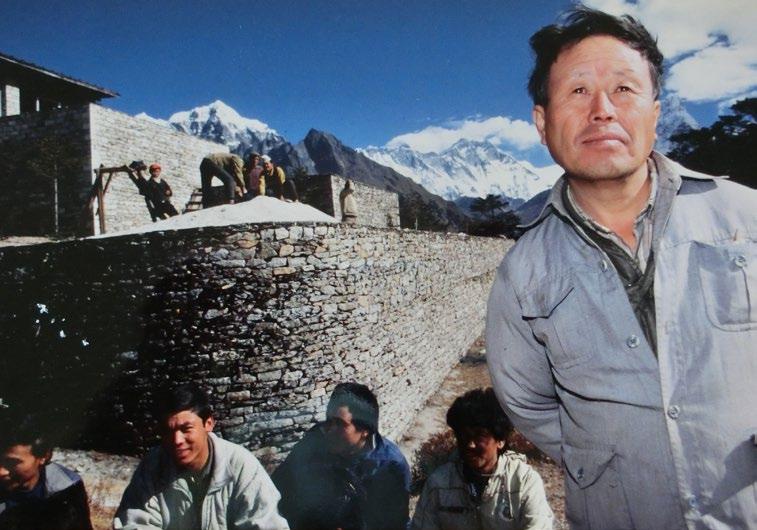

Building the WORLD'S HIGHEST HOTEL

Interview with Sonia Miyahara

BY RIE MIYOSHI

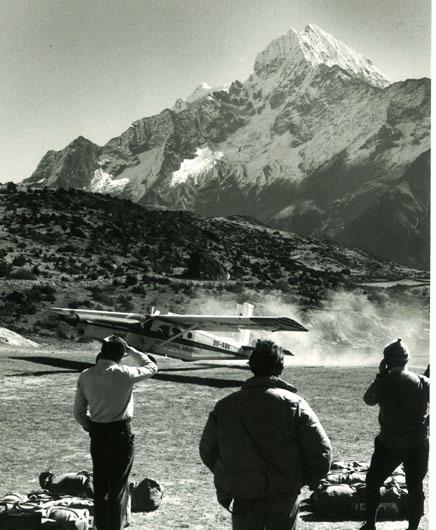

Constructing a hotel at 3,880 meters is not an easy task. Back in the 1960s it was monumental. In 1968, entrepreneur Takashi Miyahara defied expectations and built the world’s highest hotel in the Himalayas. Driven by his passion for Nepal and mountaineering, he garnered support from the local Nepalese government to not only build Hotel Everest View but also make the Himalayas a sustainable tourist destination by providing jobs to locals living in the Himalayas. The construction of Hotel Everest View took several years and relied heavily on local Sherpa porters who carried food and supplies on a two-week trek from Lamusangu.

Visitors from the world over headed to the hotel when it first opened its doors in 1971, with the 360 views of the Himalayan mountain range taking their breath away. The project was praised not only for the hotel providing stellar views of Mt. Everest and the surrounding Himalayas, but also how Miyahara’s team literally paved the trail for travelers of all ages to experience Mt. Everest.

Miyahara passed away in November 2019 at the age of 84, leaving behind his stone-terraced hotel. Hotel Everest View was listed on the Guinness Book of World Records in 2004 as the highest hotel in the world. It has been surpassed since then, but remains a popular travel destination for those exploring the Khumbu Region. His daughter, Sonia Miyahara, is planning to celebrate the hotel’s 50th anniversary in 2021 with the English release of her father’s book, "Himalaya no Tomoshibi" ("The Ray of Light in the Himalayas"). Although the book was written in 1982, Miyahara was ahead of his time as he recognized the importance of sustainable tourism. The hotel was never massively profitable, but Miyahara’s reward was each time his teary-eyed guests thanked him for the opportunity to view Mt. Everest. We caught up with Sonia on her recent trip to Tokyo at her father’s office where she was gathering old photos from the hotel construction. The 38-year-old takes after both parents, with her father’s twinkling eyes and laugh and her Nepali mother’s warm personality.

Rie Miyoshi: What was the secret to your father’s success working and pioneering tourism in the Khumbu Region of Nepal? Sonia Miyahara: M y d a d w a s passionate about supporting Nepal’s tourism and economy, and the locals saw and respected that. Of course the hotel was a big part of it, but he wanted to create something more that would help Nepal. Rather than relying on foreign aid, he wanted to create jobs for the locals, especially the Sherpa community.

He also had the support of his mountaineering friends in Japan. Some of them have passed away due to climbing accidents unfortunately. I believe my dad worked harder on the hotel to honor his friends. And whenever he had an idea, he would be on it immediately. Even when he was older, he would think of projects to work on. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, but he always used to tell me he wanted to do something no one else had done before.

RM: In his book, he talks a bit about growing up in Nagano. Did that influence him to start mountaineering? SM: His family owned — and still owns—a charming ryokan called Fujiya in Tazawa Onsen. It’s near Ueda in southern Nagano and surrounded by mountains. So you could say he had a background in hospitality. He also studied mechanical engineering which helped a lot with the hotel construction. In university, he joined a mountaineering club and later on, was chosen to go on research expeditions to Greenland and Antarctica. He e n j o y e d e x p l o r i n g N e p a l a n d eventually quit his office job to work in the Nepal Ministry of Commerce and Supplies. RM: It must have been a logistical nightmare building a hotel in the Himalayas in the 60s. SM: Yes, back then there were no access roads to Syangboche Ridge where the hotel sits. Namche Bazaar, which today is a gateway to trekking around Everest, was undeveloped

with no accommodation. They had to get to Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) first to pick up supplies and construction tools brought in from Japan, then ensure that was transported safely to Kathmandu, then eventually up to Syangboche. Everything took time and patience. My dad was a child during World War II so he experienced some hardship, and I believe that led to strength of character. He was also a minimalist, and would try to fix anything that was broken. RM: Yo u r f a t h e r b r i n g s u p a n interesting point about the Sherpa and Japanese people sharing some similarities. SM: Yes, they both are hospitable, respect and enjoy the outdoors and even look a bit similar, so perhaps that’s why Japanese hikers feel a sense of connection to the Sherpa. Of course the location is amazing, but the people definitely make the place and I think that’s why we get repeat visitors. RM: Did your father ever climb Mt. Everest? SM: He actually tried to climb it at age 60. He was really close to the summit but got snow blindness in one eye and had to turn back. But he attempted it at 60 years old, which I think is a pretty great feat in itself. RM: What was he like as a father? SM: (laughs) You know, he was a typical Japanese dad in that he didn’t show much affection and would wave me off gruffly when I tried to hug or kiss him—but he was also very kind, created lots of opportunities for me and would say that everything he did “was for Sonia.” I remember evenings where we would be reading next to each other, him with his Japanese book and me with my English book. He spoke fluent Nepali with a slight

accent, so that was what we spoke at home mixed in with some Japanese.

He let me pick which school I wanted to go to and told me I should get overseas experience. So I studied economics in Boston and worked in Tokyo and Singapore. Unlike a lot of Nepali family businesses, he didn’t force me to come home and take on Hotel Everest View after him. He knew how hard it was to build a hotel, so he didn’t want me to have that burden. I think having that upbringing though made me want to move home and help out with our family business.

My dad didn’t share too much with me about building the hotel or his past, so reading the book was an unexpected surprise. I didn’t even know he had that conversation with Sir Edmund Hillary. RM: That chapter shared a lot about your dad’s personality. He didn’t back down when Sir Hillary disapproved his hotel project. It was two great men respectfully discussing preserving local culture and nature even though they had opposing views. SM: Yes, my dad had written down speaking notes to go over with Sir Hillary but ended up crumpling his

notes up and throwing them in the fireplace! One of the things they talked about was making sure the area didn't get commercialized. They both genuinely loved the Khumbu Region, environment and people.

The hotel never became massively profitable, but my dad didn’t care. Sometimes I would joke that “It’s okay to make a little more money.” He just loved seeing people enjoy the mountains. He was also really caring about our guests; whenever we had guests with altitude sickness, he’d show concern and keep asking how they were doing. RM: Do you think he missed living in Japan? SM: He definitely missed the food. He would always come back from his trips to Japan with suitcases filled with fish, natto (fermented soy beans) and negi (long onion). Even when he visited me in Boston, he brought these ingredients over. I wondered how he snuck those through customs. RM: How do people get to Hotel Everest View today? SM: We run a travel agency so people can easily book the whole tour. First, fly from Kathmandu to Lukla, then trek

four hours to Phakding Village. The next day, you would trek to Namche Bazaar, which takes seven hours. The following day, you’d reach Hotel Everest View. We normally recommend two nights there. The whole trip takes a minimum seven days and you have to go slowly to acclimate yourself to the altitude. We also have a chartered helicopter direct from Kathmandu. A helicopter shuttle is also available from Lukla in spring and autumn. RM: What are your future plans for Hotel Everest View? SM: With the pandemic we’ve had no visitors and need to prepare for the following year. The hotel is currently closed but we’re hoping Nepal will open its travel borders next spring or autumn. We also run two travel agencies, Trans Himalayan Tour and Himalaya Kanko Kaihatsu. Until then we’re going to be working hard to survive. v

F o r m o r e i n f o r m a t i o n on Hotel Everes t View, visit www.hoteleverestview.com. To learn more about getting there, visit www.himalaya-kanko.co.jp.

SHIKOKU ROAD TRIP

Kochi by Camper Van

BY RIE MIYOSHI

Kochi has always been ahead of its time. The southernmost prefecture of Shikoku Island has long been a favorite travel destination for locals, dating back to the Edo Period when pilgrims making the 88 Temple Pilgrimage would detour to enjoy the beaches and aquamarine waters of Tatsukushi. The nature-abundant region is also known for being home to two key historical figures who supported Japan’s modernization: Ryoma Sakamoto and John Manjiro. The latter was one of the first Japanese persons to visit the United States, becoming an important advisor when Japan began opening up to the west. Ryoma Sakamoto was a legendary samurai who helped found the modern state at a time when the feudal governments of Japan were failing the people. Kochi’s progressive history has contributed to the people being warm and welcoming to visitors from all countries and walks of life.

Mountainous forests and coastal towns dominate most of the prefecture, where visitors will find enterprising locals and nature guides working to revitalize their communities. Shikoku’s winding roads are best explored by car—or if you’re traveling over several days, a camper van—from Kochi Ryoma Airport or Kochi City. Kochi has a number of campsites, michi-no-eki (roadside rest areas) and convenience stores (even in the most remote locations), which makes road tripping easy.

1NIYODO RIVER

The Niyodo River is a good first stop as it is a 100-minute drive inland from Kochi City. The phrase “Niyodo blue” has been bandied about by locals for decades as this iridescent river boasts the clearest water in all of Kochi, and is one of the purest rivers in Japan. The river runs through Nakatsu Gorge, a popular hiking and camping spot for its lava-formed boulders and cascading waterfalls. There is an easy two-kilometer trail along the river ending at the 20-meter Uryu Falls.

CANYONING WITH NIYODO ADVENTURE

Niyodo River’s first canyoning company, Niyodo Adventure, opened in early 2020, led by a dynamic husband-and-wife team, Hiro and Zoe Kanzawa. The English-guided tour takes around two-and-a-half hours in the Nakatsu Gorge, with plenty of opportunities to jump into pools, slide down natural water chutes and abseil down cliffs. The grand finale involves swimming into a cave and out through a waterfall. The course is great for beginners, but has some challenging and fun aspects for canyoning enthusiasts.

As there are no other canyoning companies here, chances are you’ll have the gorge all to yourself. If you’re feeling scared halfway, they are happy to provide alternative routes. There’s also a family canyoning option for children six and up. Canyoning tours run from April to October and peak season is in August. Tours may be cancelled during the rainy season in June and July.

Pack rafting tours are also available further downstream from April to October. It is gentle e no ug h t hat inex p er ie nce d p ad dler s c an safely learn in grade two rapids, but thrilling enough to get your adrenaline pumping. Visit

www.niyodoadventure.com.

LUNCH AT TEA CAFE ASUNARO

This cafe and restaurant overlooks the Niyodo River and is run by Noriaki Kishimoto, a local tea farmer who wanted to expand Sawatari, the family tea business, by bringing green tea to life through an assortment of dishes. On your way to or from canyoning, stop by Tea Cafe Asunaro for lunch, dessert, tea, or all three. All dishes use the Sawatari local green tea. Dine on the terrace with some fresh green tea udon and enjoy the river and valley views, or grab some takeout green tea waffles for a snack for the road. The restaurant is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and closed on Thursdays. Visit www.asunaro-cafe.com.

SOAK IN YUNOMORI ONSEN

Rest tired muscles from canyoning or driving at this picturesque, riverside onsen inn. Yunomori Onsen’s large indoor and outdoor onsen baths are said to ease chronic skin diseases, chronic women's diseases, cuts, diabetes, nerve pain, and muscle soreness. Stay overnight in a Japanesestyle room or cottage built using local wood while taking in the views of the valley. Daytrippers can enjoy the baths from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. Visit www.yunomori.jp.

2SHIMANTO RIVER

The Shimanto River in western Kochi is known as one of the clearest rivers in Japan. The 196-kilometer river star ts in the mountains and empties into the Pacific Ocean, and has sustained the livelihood of the locals for centuries. Along the river, there are a number of chinkabashi bridges. These bridges are designed without side rails to be submersible and reduce the risk of the bridge being washed away in a flood. There are 22 chinkabashi crossing the main river, and while many are modern, there remain a few built in the old style. The longest bridge is the Sada Chinkabashi, closest to the mouth of the river.

CYCLING THE SHIMANTO RIVER

Starting at Nakamura Station in central Shimanto City, rent a bicycle at the adjacent Shimanto Rin-Rin Cycle inside the tourist information center. There are eight bike dropoff terminals along the 40-kilometer trail between Nakamura Station and Ekawasaki Station and the cycling path remains relatively flat as it winds through tea fields and riverside trails. As the chinkabashi bridges have no rails, be sure to walk your bike safely across the bridge. Other ways to enjoy the river within the area are yakatabune (river boats) and kayaking. A breezy 195-meter zipline across the river was also installed in June 2020. Learn more on

www.visitkochijapan.com.

LOCAL EATS

Kochi offers fresh seafood and vegetables year round thanks to its mild climate and long Pacific Ocean coastline. While cycling along the Shimanto River, step into Shaenjiri, a cafeteria-style restaurant at the entrance of Kuroson Gorge for dishes using local Shimanto vegetables, fish and meat. Shaenjiri means “vegetable garden” in the local dialect. The food tastes healthy and brings a sense of comfort as it is prepared by local obaachans (older ladies) and is well visited by locals and visitors alike. The restaurant is open from 11:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. and closed on Wednesdays. Shaenjiri is also one of the Shimanto Rin-Rin Cycle bike drop off stations. Visit www.shimanto.

or.jp/GT/55shaenjiri/shaenjiri.html.

Back in Shimanto City, the lively Aji Gekijo Chika is a three-floor izakaya (traditional pub -restaurant) with the second floor “balcony” seating overlooking the open kitchen. This windowless restaurant was designed to look like a gekijo (theater). To supply dishes to customers on the second floor, a tray on a pulley is deftly hauled up and down. Local delicacy katsuono-tataki (seared bonito) topped with onions and garlic is a must try here. English menu available. Open from 5 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. and closed on Mondays. Visit www.ajigekijochika.

com.

CAMPING ALONG THE RIVER

Drive 20 minutes from Shimanto City to the mouth of the river for a good night’s rest at Yamamizuki, a c ampsite with glamping, auto camping and tent sites. There is a public rotenburo (outdoor bath) and two private indoor baths which you can reserve at check in. The check-in lobby is in a treehouse-like building overlooking the Shimanto River and the Pacific Ocean—a great spot for sunrise yoga. Up the coast are several popular surf spots including Futami and Hirano beaches. Irino Beach is another surf spot that is also called an “outdoor museum” where an annual T-shirt art exhibition is held on the beach.

I f y o u ’r e o n a b u d g e t , t h e

Shimanto River Camping Ground

located in Shimanto City is a free campsite located along the Shimanto River. You can pitch your tent or park your camper van here. Free bathrooms available.

3ASHIZURI UWAKAI NATIONAL PARK

Clear, azure waters with colorful coral and marine life, isolated beaches and dr amatic clif f s char ac terize Ashizuri-Uwakai National Park. The coas t al national par k s pans the southwestern side of Shikoku and includes parts of Kochi and Ehime prefectures. The subtropical waters make it a breeding ground for colorful marine life and also attracts whales, dolphins and sea turtles. Cape Ashizuri at Shikoku’s southernmost point is also a stop on the 88 Temple Pilgrimage so it’s common to sight modern-day pilgrims walking along this area with their conical hats and walking sticks.

Discover Tatsukushi Bay

Tatsukushi, in southwestern Kochi, offers a little bit for everyone. There are rocky shores making it ideal for divers and snorkelers, as well as a sandy beach for swimmers. Snow Peak Tosashimizu Camp Field is set up on the right side facing the ocean. From there, you can walk the short coastal trail to Ashizuri Underwater Observation Tower. This peculiarshaped tower is actually built seven meters underwater, so visitors can go down a flight of stairs to see fish and even sea turtles and stingrays when the waters are calm.

Back on shore, the K o c h i

Prefectural Ashizuri Aquarium,

which opened in July 2020, is Kochi’s largest aquarium and home to more than 350 marine species including the region’s famously colorful sea slugs. The aquarium and the adjacent visitor center are alternative activities for those relaxing days or when the weather is poor.

Continue along the coastal trail to see Minokoshi Coast’s sandstone and mudstone rocks that have taken on an other worldly shape due to years of erosion. The rocks are said to look like bamboo from a certain angle. Another way to enjoy this trail is to take the glass-bottomed boat departing from the port next to Snow Peak Tosashimizu Camp Field.

Ride an ATV to Kashiwa Island

Learn how to ride an ATV buggy with Lagoon Racing. If you have a Japanese or international drivers’ license, hop on a buggy to explore the western coast of Kochi. The guided tour starts off with 40-minutes of practice before heading out on the main road. Kashiwa Island is a popular destination as it has some of Japan’s clearest waters and is home to more than 1,000 types of fish. It is easily accessible via the bridge connecting it to Shikoku’s mainland.

The lesser known Kashinishi Beach also features snorkeling spots around the uninhabited Benten Island, which you can walk to during low tide. The tours are guided in minimal English and run year round. Visit

www.automaaudio.wixsite.com/lagoon.

Getting There

The easiest way to get to Kochi is by flying into Kochi Ryoma Airport. There are several car or camping car rental companies like Camping Car Life, Kochi Kurumatabi and Shimanto Rental Car. There is also a Kochi Airport Limousine Bus that brings you directly into central Kochi City. For more information, visit www.visitkochijapan.com. v

KOCHI Koyo - -

CYCLING

Rice fields transform from green to gold in the Japanese countryside of the Tosa Reihoku area in Kochi Prefecture. Tosa Reihoku is located in the middle of Shikoku Island and is composed of four towns: Otoyo, Motoyama, Tosa and Okawa. The clear Yoshino River flows through the center surrounded by terraced rice fields on both banks. Up in the mountains, Mt. Shiraga and Mt. Kuishi are dressed in fiery seasonal colors and perfect for fall trekking. The varying terrain makes this region an ideal place for cyclists and hikers of all levels. Travelers can easily explore Tosa Reihoku’s Japan Eco Track routes. The easiest way to get here is by flying into Kochi Ryoma Airport then driving to Otoyo I.C., a 20-minute drive from central Kochi. You can also take the bus from the airport to Kochi Station, then a 30-minute train ride to Osugi Station. Otoyo I.C. and Osugi Station are located close to each other and are starting points for the following routes.

COUNTRYSIDE RIVER ROUTE

This beginner-friendly cycling route starts at Montbell Outdoor Village Motoyama on the banks of the Yoshino River. This rental bike station also serves as a retail store, restaurant, souvenir shop and accommodation. The Reihoku-noyu (hot spring) is on site.

Cycle along the river to Motoyama Sakura Market for fresh produce. A 15-minute ride away is Sameura Dam and the Yoshino Climbing Center, home to Shikoku’s major climbing competitions. Take a detour upstream along the emerald Asemi River before heading back down to the Yoshino River. You’ll see one of Yoshino River’s chinkabashi (submersible bridges designed to not get washed away in a flood). Continue down to Kashino River for a stunning view of terraced rice fields at Tenku-no-Tanada Observatory. Head back north to the Yoshino River for a quick recharge at Joki Coffee before making your way back to Montbell Outdoor Village Motoyama or Osugi Station. This 38.5-kilometer course takes around three hours with minimal elevation changes.

Tosa Reihoku

SAMEURA DAM AND SEDOGAWA VALLEY ROUTE

For cyclists wanting to go further, start this route at Tosa Cycle Station located just south of Sameura Dam. Follow the Yoshino River west towards the Seto River and into Sedogawa Valley, a popular place for fall foliage viewing. The majestic Amegaeri Falls is one of the biggest waterfalls on this route. Further along the road is the Burabura Suspension Bridge overlooking the valley. This 70.5-kilometer route takes five hours and is recommended for intermediate to advanced cyclists.

MT. KAJIGAMORI HIKING ROUTE

For rewarding mountain views, climb the 1, 399- meter Mt. Kajigamori in Kajigamori Prefectural Natural Park. You can start your trail at Ryuo-no-taki, said to be one of Japan’s top 100 waterfalls. At the peak, you’ll see the Ishizuchi Mountains to the west and Tsurugi Mountains to the east. Mt. Kajigamori Mountain Hut at the 8th station offers 360-degree views. There are also cultural treasures along the trail such as Sadafukuji Temple’s Oku-no-in and Mikagedo Temple. This 4.6-kilometer trail takes roughly three hours and is relatively easy.

ABOUT JAPAN ECO TRACK

Montbell—Japan’s largest homegrown outdoor brand and retailer—started a series of events in 2009 called Sea to Summit. The goal was to invigorate local areas, holding events to experience nature through canoeing, cycling, trekking and other human-powered movement. While these events continue to be held in beautiful areas around Japan, the natural progression was to provide information and guides so travelers could experience these areas throughout the year at their own pace while learning the history and culture of the region and interacting with locals.

Japan Eco Track guides contain maps with designated routes of varying difficulty levels. Each guide includes information on local restaurants, guides, tour operations and other attractions. Along Japan Eco Track routes there are support stations located at affiliated stores and major transportation hubs such as train stations, airports and michi no eki (rest areas). Discounts and special offers are available at participating locations when travelers show the Japan Eco Track booklet. There are more than 15 guides, with new areas being developed and offered in English. For more information, visit www.japanecotrack.net.