26 minute read

I Miss You Podcast

from OFM May 2021

photos by Julius Garrido

Relationships, Recovery, and Ritual Served in I Miss You Podcast

“Ihad a series of fever dreams, and this sort of came to me; I woke up the next day and said, ‘I’m going to do it.’ I didn’t second guess anything, knowing that I would also be making myself vulnerable to whatever failures might come along with riding the train,” explains John Moletress (they/them). As an artist, musician, and writer, Moletress has experienced many journeys on the creativity train, and they also know that it doesn’t always produce fruitful results. This project, however, felt like something they could really sink their teeth into, and find a space that combined not only interest, but exceptional talent amid a time where we’ve all felt a bit disconnected. “I was in the midst of working on another podcast, and while that didn’t come to fruition for a number of reasons, and so I had this knowledge already going. Although there have been some adaptations, some changes, and fluidity through the process, I’m still on the ride,” they say. That ride began in late January 2021 as the I Miss You podcast, a weekly show about reconnecting during the pandemic. Reaching out to people who have impacted their life, including friends, ex-lovers, teachers, mentors, neighbors, chosen family, and even biological family, Moletress has chosen to find the answer to the question, “I wonder what ever happened to so-and-so?” I consider myself a connoisseur of podcast: an avid and eager listener of conversation. To be a fly on the wall and stretch outside my universe and materialize into someone else’s has always been of interest to me. While listening to I Miss You, I found myself satiated with not only the diversity in guests that Moletress reconnects with, but the depth of the conversations and how each episode is both authentic and intrinsically unique. “I had one rule, and my rule was that I wasn’t going to be exploitative, and I wasn’t going to be sensational. I wasn’t going to bring people on and then try to trap them into some weird, sensational discovery thing, and because of that, I’ve kept the container of the conversation really open,” they explain. “I came up with two questions as bookends: the first was, ‘How is your pandemic going?,’ and the final question of the conversation towards the end was, ‘What is one thing that you hope for in 2021?’” Deciding that they weren’t going to guide the conversation, instead, they would be very intentional about listening. To their surprise, conversations naturally went to a deep, genuine, and vulnerable place. It was also in these conversations that Moletress realized that some topics may require a bit more background information and detailed explanation, which is where they came up with the idea of bonus episodes. “There’s a series with friends of mine, and we all find ourselves a part of the radical faerie community; I realized that a majority of people will probably have no idea what that is, and it comes up in four different conversations because they’re all connected in some way to this group. I’m like, ‘I need to do a bonus episode that gives a sort of fast and loose history, or some type of description, of what the radical faerie movement and community are,’” they explain. In addition to providing some backstory and education about a particular part of the conversation, another bonus of the bonus episodes is it becomes a space where Moletress pulls the curtain back to their own thoughts, feelings, and reflections after the conversation with guests has ended. “What happens now that the cat’s already out of the bag? What happens now that I’m in a vulnerable state? Because being able to dive into conversations with friends and chat about some things that might have gone unsaid before doesn’t make anything easier, and it doesn’t make the relationship easier. What it does is surfaces all of this other stuff around the issues that then once we hang up the phone, I have to then carry with me to the gym and to the grocery store,” Moletress says. “

Season One unfolded before Moletress as a survey of people who have come through their life; friends from junior high and high school to people who have been significant in the last few years. Additionally, they have spoken with people whom they have never met, such as Queen Co. Meadows, Haitian Vodou Spiritual Worker and Harry Gay, a Londonbased activist, DJ, and founder of Queer House Party. Plans for the next season of the show could take a stark left turn from reflection into learning. “Where I would like this to go is, just in the past two years, I came to find my biological siblings and biological mother. I’ve had a conversation with my biological sister, but there are many other people in that lineage who I don’t really know. So, I want to start off charting of my biological family and other lineage,” they say. What makes Moletress and the I Miss You podcast uniquely interesting is the fact that they are a student at heart, a being that is tapped into not only the art of listening, but in the craft of observation, fluidity, and movement. They acquired an MFA in dance at George Washington University in D.C., and after teaching for a time, decided to utilize their movement background and migrated into a therapeutic direction of Somatic Psychotherapy. Unlike talk therapy, Somatic Psychotherapy is a holistic, therapeutic approach which incorporates a person’s mind, body, spirit, and emotions in the healing process.

“I’m still discovering things as I go along, because there are so many aspects of the therapeutic field to navigate and find your way around. This actually comes up in the podcast: I’ve been doing this deep dive into transgenerational and intergenerational, ancestral trauma, collective trauma,” Moletress says. “Yes we’re here, we’re all individuals, and Americans all live in these radical, individual bubbles; but we are connected. We’re connected from things, events, experiences that happened, generations ago.” Things from our ancestral past still have a profound effect on our nervous systems, they explain, and digging into that history can really allow us to ourselves to deep healing. As Americans, we are taught to “pull ourselves up by our bootstraps” and “figure things out for ourselves,” and oftentimes, we aren’t recognizing that issues and problems aren’t solely of our own making. Moletress wants to help others by guiding them through the process of understanding that we can be more gentle with ourselves by accepting that there are a lot of environmental and ancestral things that are outside of our control. By gaining an understanding in how we work intrinsically, fundamentally, and elementally, folks can feel more empowered. As a way of honoring the ancestral and elemental influence, Moletress taps into magic and witchcraft as a way of making an intentional, ritual-based connection to the Earth, and to themselves. “Ritual, for me, really is about stopping and being in the liminal space for a moment to give gratitude where gratitude is due. To tune into what it means to be living on the Earth and being in relationship with things,” they explain. “Also, it helps to slow down that inner self-critic, and too is the idea that I have a choice. I have an opportunity to shape my life and my experiences in a certain way, and I don’t need to walk around every day with crippling anxiety, with a sense of dread, and not knowing where I’m going from day to day. I can just focus my energy in a way to really benefit from all of the great things that are going on around me.”

Through ritual, Moletress was also able to let go of something that was no longer serving them: the use of alcohol. In I Miss You, Moletress does not skirt the fact they are an addict in recovery. Performing a ceremony on the beach of Cape Cod in December 2019, they used this as a chance to listen to their inner voice and let go of the hurt and suffering. They explain the details of what led to that day, and what ritual ceremony provided them in the end: “Drinking, for me, was ongoing because it was a way to not deal with all of these trauma fragments which were running the game for a really long time. I don’t really think there was something that happened where I was like, ‘I need to quit now or I’m going to die,’ but I got to the point where I was like, ‘I need to heal; this is exhausting; I’m sort of over it. I need to stop just numbing out everything and deal with it.’ I knew that I wanted to go to Cape Cod, to Provincetown, over New Years to see some friends, so I came up with this idea to do this ritual on the beach and ask the sea to take these aspects of suffering away from me, so I could begin again with the new year without all of the fear and sickness that came with the ways in which I was numbing everything so I didn’t have to feel it.” They continue, “It was very Tempest-like; a huge storm came through, and I found this wooden staff on the beach. I picked up the staff, drew a line in the sand, and said what I wanted to leave behind. I crossed that line, going closer to the ocean, and eventually, I just went into the ocean. The tide was coming in, and the idea was that the tide would come in and would wash away those things out to sea. And it’s worked. I really give gratitude to whatever powers that be that it worked.” While Moletress didn’t notice an immediate impact to their creativity after getting sober, the pandemic has played a big part in allowing them the time to focus that creative energy, and in turn, continue that inner self-work. “Doing the ritual was one thing, and making an intentional decision to stop drinking was one thing, but it wasn’t a magic eraser. I had to reshape my entire thinking around what that aspect was in my life; what it was doing and what it was not doing for me. The way in which I did that is a very personal psychology, and other people might not agree with me in the way that I think,” they say. “It wasn’t my intention to turn this into a podcast about addiction, but it keeps coming up in some way.” Speaking honestly about their struggles with alcohol and the way in which they find healing from addiction is just another example of the raw and authentic conversations that I Miss You features. From reconnection, to ritual, to recovery, there is no stone that is left unturned. What started as a fever dream, that transformed into an idea, that then created a podcast that brings hope, humility, and humor to listeners around the world has found a home nestled in a medium which honors truth, tragedy, and triumph.

Learning She

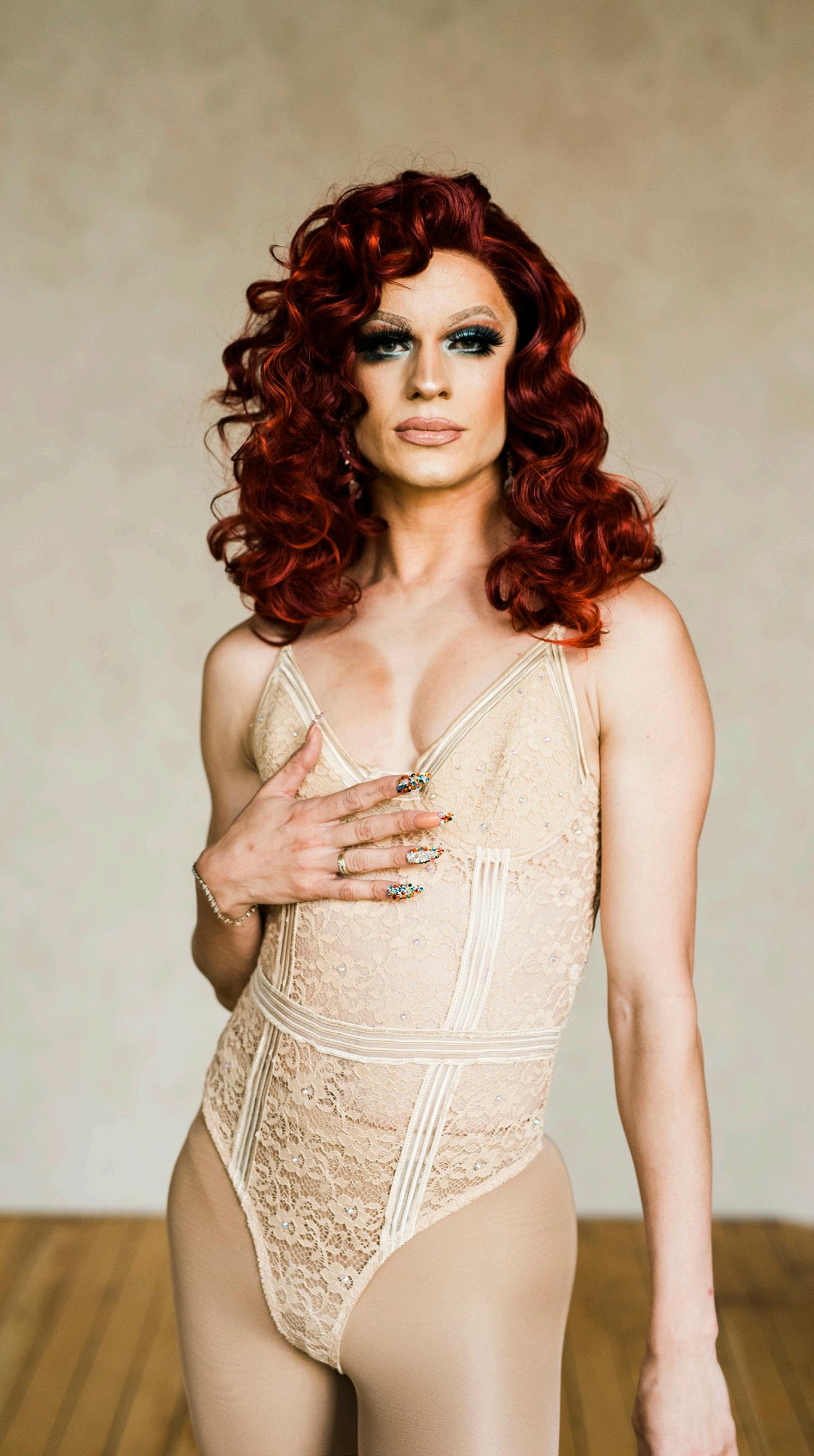

photos by Apollo Fields by Veronica L. Holyfield

Broadway actor Mykel Vaughn (he/him) has yet to introduce She to the public. Keeping her safely tucked away to the confines of his New York apartment, he is still being taught who She is, the dame he is creating, and the performer who is itching to be seen. “She’s still brand-new, in a lot of ways, so I still don’t fully know who ‘She’ is,” Vaughn says. “I’m letting her just kind of develop as it happens.” While She has made seldom and brief public appearances, Vaughn mostly keeps his time as her under the radar, developing his techniques and finding a feminine expression that feels grounded and authentic. Identifying as a gay man, he understands that in many ways, She is different from him, and is also him at the same time. “I’m still learning how to manage her because I myself am a very bubbly, kind, warm person. I’ve learned that, when She is fully done up, people are a little intimidated by her,” he explains. “I realized that I have to kind of calm She down and allow people to go to her because She scares people off, otherwise.” Vaughn got his start as an entertainer at the North Carolina School the Arts and formed his queer presentation around the need to “play straight” in order to get good roles in the acting community. He explains that he had acquired an outlook that performing hypermasculinity was the only way to be taken seriously. After moving to New York after college, he made friends with some of the local queens and eventually roomed with three performers who were in Kinky Boots on Broadway. “One thing led to another, and I did what pretty much every gay man does in New York, and I made myself a drag queen for Halloween. I looked at myself in the mirror, and I was like, ‘I look really pretty,’” he explains. “As time has gone on, every time I do drag, I get such an overwhelmingly positive response on the looks that I do.”

Exploring wig options, makeup styles, and costume design, Vaughn increasingly became more interested in the art of self-expression as he increased his capabilities of transformation. Unlocking creativity through discovering the ways in which She reveals herself to him has proven multifaceted and informative. “The more I’ve embraced that femininity in my life, the stronger the masculine side of myself has become. It’s almost like a rubber band, being stretched in both directions,” he explains. “Drag is such a political statement in and of itself. I’ve gotten to understand toxic masculinity so much.”

Using the example of experiencing men hollering at him when he is dressed as She, donning a sexy dress and heels, he has been able to briefly step into a woman’s world. “As a drag queen, there is an element that, of course, I want the attention. I spent the past six hours making myself look like this, and the entire thing that you’re looking at is an illusion, but I’m thinking to myself, ‘Something’s got to change.’ It’s not appropriate to just say whatever the hell you want to a woman just because she looks beautiful,” Vaughn says. “Also, just my appreciation, there’s some women in the city that run around in these high heels, and I think to myself, ‘Oh my God, you are a superwoman.’ All of the pain that comes with the beauty, or the fashion, and just how strong these girls are that just rock it every day, and that’s just what they do. I think it’s amazing.” In capturing the essence of She, Vaughn reached out to New York-based photographer Heather Huie (she/her) of Apollo Fields, and the two quickly began to brainstorm an interesting and unique way of telling his story. As part of the “Come As You Are” series, the pair landed on highlighting an area of drag which is rarely shown: de-dragging. They decided they would allow us viewers to become voyeurs to the process of removing the charade, the unbecoming of the persona and the transferring back into the person. We see the removal of the heels, the stripping of the dress, sliding off the wig, wiping off the makeup, and the undoing of the tuck … areas of the body which emerge again only behind closed doors, now is performed before the unyielding truth of the camera. “It’s an interesting concept because there’s so many shoots that you see from man to woman, but you see from the building of the woman, and we don’t really think about the relief that it is to take it off,” Vaughn shares. “Sure, we’re looking at the lens of particularly a drag queen, but you know that happens with any human. You have your mask, whatever you present yourself to the world as, and when you get home, you can shed that down to your bare self, and get to relax and breathe.”

As part of the photo essay that is posted on the Apollo Fields website, Vaughn exercises his creative writing muscle through an accompanying blog, personifying She and sharing a firsthand account of the process of de-dragging.

“We were talking about it, and reflected in his writing, is this idea of, ‘I never take off any article, any accessory, anything at all until I am behind my own closed doors again.’ You know, you can’t be half of a queen in the Uber,” Huie explains. Vaughn’s experience of finding an evolving version of himself through She, and flaunting his unapologetic self in and out of drag, is a precise example of what Huie was hoping to unveil in the “Come As You Are” series. “I started to get into the boudoir industry a little bit, and I started realizing a lot of it didn’t totally align with my personal values,” Huie explains. “A lot of what I was seeing out there was actually not really that empowering. It was a lot of people getting into lingerie for the sake of getting into lingerie for somebody else’s purpose, and not really for themselves. So, I wanted to dial that back and put an emphasis on that we’re doing this for ourselves, first.” Additionally, Huie was experiencing a lot of folks who wanted to wait before scheduling a boudoir session so they could hit the gym and tighten areas of their body, or generally lose weight in order to feel sexy. She would also receive requests from clients to Photoshop their bodies or digitally alter their photographs after the session, and that approach did not resonate with Huie in the slightest. So, the idea of “Come As You Are” was where Apollo Fields has truly found a beautiful space for their clients to explore all different concepts, ideas, and characteristics.

Every photoshoot comes with a backstory, a deeper look that what the eye sees, and to give space for that, Huie has added the benefit of a written blog post for more of that story to be told. Typically written by Huie, she asked Vaughn to write the narrative to his own “Come As You Are” session, giving She the platform to fully express herself as the woman in front of the lens. “One of my favorite things from Mykel’s session was just like the simplest, lovely sentence of, ‘I love being gay.’ That’s not a complex sentence, but it is. It was just so genuine; it can be this wonderful, amazing part of somebody’s life. It’s not all struggle,” Huie says. For Vaughn, de-dragging in front of the camera wasn’t a challenge. As a gay man, he has gone through his own process of learning to love his body, and similarly to many of Huie’s early boudoir clients, he has felt the pressure from gay culture to conform to expectations. “The gay culture has a huge body dysmorphia problem; if you don’t have a six- or eightpack, and you aren’t six-foot-two, you kind of just don’t matter,” Vaughn explains. “And then, on top of that, there is a lot of what we call ‘bottom shaming,’ the bottom is the lesser, or the bitch, or the female, which is just terrible. First of all, even in a straight relationship, I think a man should uplift his woman, and just because penetration is happening doesn’t mean that she can’t be empowered, or be dominant. Just as I think in a gay relationship, in a lesbian relationship, a pansexual relationship, or whatever it is. “I think that for a lot of our older, gay males and mentors, they had to blend into society to not cause a ruckus and to get ahead in the business world. Therefore, they had to put on that toxic masculine suit, figuratively and literally, just to be respected. That, unfortunately, I think has brought itself into the gay community,” Vaughs says. Experiencing a shift in attitudes, though, Vaughn does feel that those barriers are breaking down, as the younger generation has fewer hang-ups about gender expression and leans more into a fluid form of identity. From things as simple as gender-bending haircuts to seeing more accessibility when it comes to makeup, shoewear, and clothing options, he feels inspired and less inhibited in living out loud and letting She flourish. “It’s exciting, and it’s inspiring me; if I wanna wear a dress today, then I’m gonna wear a dress today. It is what it is,” he says. She is many things. She is expression; She is creativity; She is feminine, and She is masculine. As Vaughn continues to learn She, he can proceed with passion, rather than with fear, and that is what most of us hope to grow into as we learn ourselves, and each other.

30% OFF FOR NEW CUSTOMERS*

by Denny Patterson

In December, former two-time, U.S., national champion and Team America member Hig Roberts became the first elite men’s alpine skier to publicly come out as gay. In an exclusive interview with the New York Times, Roberts said he decided to choose happiness over living a lie. He opened up about struggling with his sexual identity and hopes to create a more inclusive sports environment for athletes, and he is encouraging others to be themselves. Raised in the skiing mecca of Steamboat Springs, CO, Roberts had a successful ski racing career. He was recruited to the U.S. Ski Team after college and skied the World Cup circuit, going on to become national champion in GS and slalom in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Skiing was a safe haven for Roberts, a place of freedom and escape. However, with the rise of his ski racing career and two national titles under his belt, Roberts did not feel like a champion. Being in the closet took away a lot of the experience and joy he could have experienced. Guilted by shame, not living an authentic life took a staggering toll on his mental health. OFM had the opportunity to catch up with Roberts and see how life has been since coming out and how he will bring LGBTQ visibility to the world of sports.

How has life been these past couple months since coming out?

It has been great. Honestly, telling my story, it was not something that I fully expected to do or go the way that it did. I got to that point by being vulnerable and being able to openly express that to not only my closest friends and people that were around me at the time, but also other athletes who went through similar experiences. I feel very grateful to have been given that platform to tell my story, which I think was a very important narrative that I wanted to get out to the world. I think the biggest thing that has changed since the story came out was, it has given me the opportunity to start fresh with a lot of things in life. Reconnect with people who I previously worked with or competed against and begin to describe to them more in-depth what was going on with me and team up with them to make the sports world a better space in the future. I have also connected with some great advocacy programs and platforms. It has been very exciting.

What made you feel like this was the right time to let the world know that you are gay?

Because I was ready. I had buried a big part of who I was for so many years, and it caused a lot of shame and very difficult things for me—physically, mentally, and emotionally. Once I was able to work through that and understand that this is who I am—I am ready to be that person; I am ready to let go of all that discomfort that I was feeling within the professional athletic world—I felt an obligation to share that story. At the end of the day, I want to give back to the sport of alpine skiing in a way that is not completely focused on myself or interested in goals of achieving medals and awards but giving back in a way that can potentially change the space for the betterment of other people in the future. This made the timing feel appropriate. Once I was able to articulate exactly what this journey was and what it meant to me, I was ready to do it.

You have mentioned in other interviews that you began to question your sexuality at age 12. Do you remember the first time you thought you may be different?

It is hard to exactly know the right age, but I knew I was a different kid. Not just with my sexuality. I have a twin sister, so I had a direct comparison to me all through growing up, and I recognized that I was not like my teammates around that age as well. It has been an interesting thing to explore because at the time, I rationalized it with quite a bit of ease knowing that I had a wonderfully accepting family even though I never knew anyone in my family or in my small town who identified anything other than straight. To recognize that I was going to be OK, it was a great thing, but also because of the lack of visibility or representation around me, I did not necessarily know how bringing that to my family or friends would work. It was not until I got older and became a professional athlete when things started to get a little more complicated in terms of my relationship with my sexuality. That ease that I had at a young age essentially disappeared when there was more at stake involving my identity and where I was trying to be successful.

You received such positive responses from people around the world. Were your family and friends just as supportive?

Yes. It came together very quickly, and I received word that the piece would be in the New York Times maybe two days before it happened. It was an easy day for me, and I slept in past my alarm because I forgot it was happening. I was so

ready for this moment, and it was even more rewarding to share it with my family, closest friends, and everyone who went through this process with me. It was phenomenal, and they all chipped in to help me connect with other family members and friends. It was a very gentle time in my life, and it was very rewarding to have that support.

You touched on it a moment ago, but can you talk more in-depth about the emotional and mental challenges you experienced by being in the closet?

I became a professional athlete post-collegiate career. This activity, this sport that I did, suddenly became a career, and my career was on the line every single day that I was out there on the hill. It heightened everything in my body. It heightened the way I thought about how I existed in the space and what I needed to show other people. In a lot of ways, I was already so much on the outside within the Team USA structure. I was a collegiate athlete who made it, I ran into some funding problems, I had an interesting schedule compared to other athletes, and I had a brother who passed away. I was very much dealing with that on my own because I felt like I did not have the support or resources within that realm. It was basically this massive dissonance of confusion in my brain about how to survive in a sport while being so different. I was fearful that my sexuality would lead me to lose sponsorship opportunities, or I would have coaches and teammates who were homophobic and did not want me in the same environment as them. It made me incredibly stressed and anxious, and it took away a lot of the focus that I should have had on competing and reaching my potential. They were hard times during those years.

How has coming out impacted your mental health for the better?

The best piece of advice, and this is relatable to anyone in this world: being authentic and being able to look in the mirror, love yourself, and be your biggest fan is so critical for anyone. For me, being honest about who I was and leaning into that for the first time has allowed me to just love and believe in myself more. I can look back on my ski career and other parts of my life and think, I was not able to give life my full attention and I was not able to reach my potential because I was not being honest with myself or with the people around me. Letting go of that is very critical to having a great mental state. Coming out is a process, and I have learned it is a journey. I am learning every day more about who I am and what it is I want to do. It is exciting, and I made the right decision to do it. I encourage people who are in the same spot to take the time to do it at their own pace and to find a great community and realize that there are more people out there who are going to love you and accept you and embrace this bravery and commitment to being authentic than you could ever imagine. That is a huge lesson I learned. I discounted how many people out there would love and support me when it happened, and I wish I had given that more of a consideration long ago.