7 minute read

SERGEI BELOV

Sergei

Belov

Advertisement

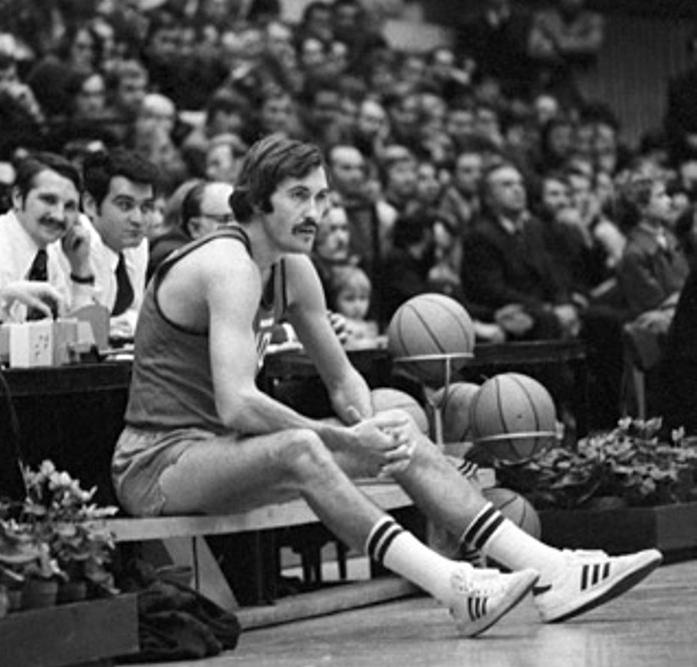

Officer and gentleman I n 1991, FIBA published the results of a survey of their own about the best player in the history of FIBA basketball. The name at the top of the list was Sergei Belov, the great captain of CSKA Moscow and the USSR national team. Today, the result would probably be different, but nobody can deny that Belov is among our sport’s greatest ever. The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield recognized this fact by inducting Belov in 1992 as the first European player ever to be includ ed there. I had double luck: first I followed him as a player from 1967, the year of his debut with the USSR at the World Championships in Uruguay, until he retired after the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. I saw him in his most glori ous moment, as the last carrier of the Olympic flame to light the torch at Lenin Stadium in Moscow, and also in his last games with the national team. After that, I met Belov as a head coach. We have spoken many times, but never like we did during EuroBasket 2007 in Madrid, where he gave me an interview for EuroLeague.net that caught many people’s attention all over Europe. From a difficult childhood to glory Sergei Aleksandrovich Belov was born on January 23, 1944, in the village of Nashekovic, region of Tomsk. Before giving birth to Sergei, his mother survived the famous siege of Stalingrad with her elder brother. The father, an engineer, worked far from home and the family

got back together in 1947. The gift for the small child was a football, something scarce and valuable at that time. Sergei wouldn’t part with his favorite toy. He was a goal keeper, but he also was into athletics, specifically the high jump. However, his quick growth to 1.90 meters de cided his future. He started to play basketball and didn’t stop until the end of a brilliant career. His first coach was Georgiy Josifovitch Res. In the summer of 1964, while in Moscow to study, Belov was seen by Aleksandar Kandel, the coach of Uralmash in the city of Sverdlovsk, and he called Belov for his team. The promising teenager ac cepted and in the 1964-65 season debuted in the Soviet first division. In the summer of 1966, Belov made his debut with the USSR national team and in 1967 he was already a world champion in Uruguay with an average of 4.6 points. He scored a total of 32 points in the tourney, with a high of 11 against Japan.

In 1968, another key moment in Belov’s life took place – he signed for CSKA Moscow. For the following 12 years, he would be the best player of the Red Army team under colonel Alexander Gomelskiy on the bench. Belov, like other players, was also an officer in the army, even though his only profession was playing basketball. In 1969, in Barcelona, he won his first European crown against Real Madrid. In an unforgettable game that CS KA won after double overtime (103-93), with big man Vladimir Andreev as the main star, getting 37 points and 11 rebounds. Both Belov and Andreev played the entire 50 minutes. Belov finished with 19 points and 10 rebounds. The following year CSKA lost the final in Sarajevo against Ignis Varese 79-74 with 21 points by Belov. However, in 1971, the Red Army team won the title back after beating Varese in Antwerp 67-53. Belov scored 24 points, but he also acted as a coach due to some problems for Gomelskiy at the Russian border.

101 greats of european basketball101 greats of european basketball Sergei Belov

In 1973, he played his last final with CSKA, of course against Varese, and lost in Liege 71-66 despite scoring 34 points.

Three seconds in Munich, 1972 Sergei Belov was a player ahead of his time. He was a shooting guard, but also capable of playing point guard or small forward. Just like Dragan Kicanovic, Mirza Del ibasic, Manuel Raga, Bob Morse, Walter Szczerbiak and other shooters from the era, they had to play without three-pointers, which were introduced by FIBA during the 1984-85 season. He was unstoppable in one-onone situations and after the dribble, you could count on an assist or a precise shot, many times with only one hand. He was also a great rebounder, but his best qual ity was his cold blood, his 100 percent concentration in crunch time. His teammates always looked for Belov for the last play or the last shot. He was a leader who transmitted security and confidence to the rest of the players and true fear to some rivals. He was a player re spected by all, because of his qualities and his behavior. He was a true officer and gentleman.

With the USSR he won 18 medals: Four Olympic medals (gold in 1972, bronze in 1968, 1976 and 1980); six in World Championships (two golds – 1967 and 1974 – three silvers and one bronze); eight at European Championships (four golds, two silvers and two bronz es). In total, he won seven gold medals, five silvers and six bronzes in the most important international competitions. His only Olympic gold was from Munich against the USA in what was a famous final because of the last three seconds were repeated under the orders of William Jones, then the secretary general of FIBA. In September 2007, Belov told me the story of the most famous three seconds in basketball history: “Jones’s decision was totally fair and correct to me. See, when Doug Collins scored to put his team ahead, 50-49, there were three seconds left and the score board showed 19:57. Ivan Edeshko put the ball into play and I was close to midcourt, the table was behind my back. I got the ball and right away, the horn from the table stopped the game. But it was not the end, there was a mistake because the clock showed 19:59. There was one second left, but we protested a lot because it was clearly a mistake. The time had to start running when I touched the ball and not when Edeshko threw it in. After what to us seemed a never-ending moment, Jones lifted his three fingers and said we had to re peat them. The rest is well known. This time Edeshko made a long pass to Sasha Belov, who faked between two Americans, who in turn jumped at the same time almost clashing one against the other, and he scored the basket that was worth a gold medal.” Disappointment at home, 1980 If his most glorious moment was that 1972 gold at the Olympics in Munich, I am sure that his biggest disappointment was the Olympic Games played in Moscow in 1980. Playing at home, the USSR lost first to Italy in the group stage and later against Yugoslavia af ter overtime, and so missed the title game. Some days later, he received an offer that was, in fact, an order:

“I got a call from the USSR Sports Minister, Sergei Pav lov, and he literally said, ‘From this moment, you are the USSR national team coach.’ And I rejected it on the spot. The minister insisted and he repeated his offer constant ly. Gomelskiy found out about the issue and, through his connections, he made it that the KGB wouldn’t allow me to leave the country for several years... I was an officer in the Soviet army and it was easy to do that. Those were

the worst years of my life and now I can say that for five years I even feared for my life!”

The darkest period in his life also coincided with the comeback from Brazil of a USSR emigrant, a friend of his. Sergei greeted him at home and this was a suspicious act for what he called “the usual services”. His problems lasted until 1988, when he returned to CSKA as coach. In 1990, he coached Italy and in 1993 he was back in Russia, where he became president of the Russian Federation until 2000. He was also the national team coach for the World Championships of Toronto in 1994 and Athens in 1998, where Russia won silver medals, and also for the 1997 EuroBasket in Barcelona, where it won the bronze. From 1999, Be lov joined Sergei Kushchenko as general manager and

president, respectively, to build a great team in Perm, Ural Great. Their team broke the dominance of CSKA Moscow, won domestic titles and played the new Eu roLeague in 2001-02 as the first Russian team in the competition. Belov lived in Perm until he passed away in 2013 at age 69.

He never had doubts that he, as well as other talents of his generation like Kresimir Cosic, Drazen Dalipagic or Dragan Kicanovic, could have played and triumphed in the NBA, just like Arvydas Sabonis did, getting there at 31, or Pau Gasol, Tony Parker, Dirk Nowitzki, Vlade Divac and so many other Europeans who showed that good basketball and good players are not an Ameri can-only privilege.

101 greats of european basketball101 greats of european basketball Sergei Belov