31 minute read

Dr. Phil Schlechty’s

Dr. Phil Schlechty’s Influence to Continue Through Educators and PAGE Professional Learning

By Craig Harper, PAGE Director of Communications

PAGE and the world of education lost a great thinker and treasured friend when Dr. Phil Schlechty passed away in early January. Schlechty was the founder and leader of the Schlechty Center. His teaching — on student engagement, teacher and leader collaboration, and intentional design of meaningful work that leads to profound learning — forms the foundation of all professional learning at PAGE.

“Phil’s research, thinking and student engagement framework formed the bedrock of my approach to education transformation since I first heard Phil speak more than 25 years ago,” says PAGE Executive Director Dr. Allene Magill. “I will miss my conversations with Phil. I learned so much from ongoing discussions about teaching and engagement. He never stopped observing and asking questions.”

Phil and his associates at the Schlechty Center began their partnership with PAGE 15 years ago. George Thompson,

Dr. Phil Schlechty, founder of the Schlechty Center

president of the center and a former Gwinnett Public Schools superintendent, has been closely involved with the work

PAGE and Schlechty Center Beliefs

• Help leaders understand how their role helps create a focus on students and on the quality of experiences provided to students and staff. • The best way to increase student achievement is to provide students with work that engages them and results in a profound grasp of knowledge. • The best way to attract and retain great teachers is to ensure that they are engaged in their work and love their jobs. • Professional learning focuses on leadership at all levels, from the classroom to the boardroom.

from the start. “Along with the rest of us, Phil was proud of our partnership with PAGE,” Thompson says. “Phil was also proud of PAGE for becoming a national example of how a professional organization cannot only help educators grow, but serve as a catalyst to improve the lives of children and families. Using professional learning as a platform, PAGE demonstrates both the academic and community-building purposes of public education that Phil talked and wrote about. ... He was proud that our partnership with PAGE is grounded in mutual beliefs and commitments.”

ENGAGEMENT PRECEDES LEARNING

As educational leaders reflected on

Phil’s influence on their practice, several themes emerged: Phil made people think about why they held their beliefs about education and learning. He was constantly learning himself and checking his thought process. He made himself available to everyone who cared to engage with him. Participants at conferences or meetings — whether an experienced superintendent or a first-year teacher — would find themselves deep in conversation (or debate) with Phil regarding education.

“By listening deeply, Phil would frequently lift gems of wisdom from others, and he made sure to give them credit, on the spot, publicly or privately, or in print,” says David Reynolds, director of impact studies at PAGE. “The fact that he sincerely sought the opinions of others to help him tweak his own thinking, or at least how he communicated it, shows how much Phil valued learning.”

Ricky Clemmons leads the High School

‘When Phil’s frameworks for designing work and engaging students are applied districtwide, the result for children and teachers is magic.’ – Bill McCown, PAGE Professional Learning Staff Member and Former Superintendent of Gordon County Schools

Redesign Initiative and other professional learning with PAGE. He, too, experienced Phil’s interactive teaching and learning style. “I’ve learned much about the depth of Phil Schlechty’s thinking, but it amazes me that I learned something new and more in depth each time I heard him speak. His analogies and stories spoke to the way I, and many others, learn,” Clemmons says. “I’ve heard him say many times that engagement precedes learning. His ability to engage you in his teaching modeled the framework he advocated.”

Clemmons also recognized Phil’s approachability. “He could converse with you as a peer, a learner or as a friend. He took the time to have one-on-one conversations with educators of all levels.”

THE RESULT IS ‘MAGIC’

Gordon County Schools committed to a districtwide effort for student engagement and collaboration while Bill McCown was superintendent. McCown, who now works with PAGE’s professional learning staff and Metro RESA, says tendent, first met Phil during Hawkins’ “When Phil’s frameworks for designing first superintendency in Texas. Hawkins work and engaging students are applied came to Georgia, in part, to continue to districtwide, the result for children and work in a district using the Schlechty teachers is magic.” Center framework. “Phil brought clarity,

McCown says Phil’s genius was in developing systems and tools to make the collaboration, design, engagement and analysis ‘Phil brought clarity, confidence and hope to process accessible to school staff, which allowed staff to develop their own solutions a new superintendent who intuitively knew the to instructional challenges with students. “Because he had the ability to create sysvalue of mental models and frameworks, but who tems and tools to articulate had been unsuccessful at his thoughts, school leaders with the desire to focus on cobbling together a way to designing engaging and think about all the things of meaningful work for students could truly transform education and school.’ the educational experience – Dr. Jim Hawkins, Superintendent for students.” Dr. Jim Hawkins, Dalton of Dalton Public Schools Public Schools superin-

Continued on page 8

By George Thompson, Schlechty Center President and COO

Since Phil Schlechty’s passing in January, expressions of appreciation have poured in from educators. The most frequent comment has been, “He changed the way I think.” Phil had a gift for helping others reframe problems and see opportunities in challenges. He had little patience for those who were certain that they had everything figured out. He was passionate about the importance of public education, but he did not see school as having only an academic purpose. He understood that the community function of school was at least as important as the academic function. He believed educators need to do more than serve the community: They need to build community.

A key to Phil’s success was his ability to communicate with any person or audience. He once told me that in his early work, he found himself writing to please other professors. It was when he understood that his audience was practitioners, especially teachers, principals and superintendents, that his ideas gained acceptance. He also understood that practitioners needed tools, frameworks, professional development, leadership development and moral support in order to institutionalize the ideas that he was writing and speaking about. It is for this reason that he founded the Center for Leadership in School Reform in 1988. The center was renamed the Schlechty Center in 2004. Phil’s writing stimulated the design of many Schlechty Center tools. He would also say that the design of the tools stimulated his thinking and writing.

confidence and hope to a new ‘He believed in the steady and knew that it takes community superintendent who intuitive- collaborative work of schools, support. He warned against ly knew the value of mental models and frameworks, but who had been unsuccessful and knew it was hard, and knew that it takes community the encroachments of far-away powers that knew how to mandate but nothing more. at cobbling together a way to think about all the things of education and school,” support. He warned against the encroachments of far When I read his books, I recognized that he had wisdom, knowledge, insight, vision, and Hawkins says. “The center he established provides extensive and excellent tools that away powers that knew how to mandate but nothing more.’ [that] all of that was grounded in a lost quality: common sense. We have lost a friend.” help build my capacity and the capacity of my district to become a great learning organization and public school – Diane Ravitch, Education Historian and Research Professor of Education at New York University The importance of building strong relationships anchored Phil’s work. Quality relationships foster trust, collaborasystem.” tion and community. He

Diane Ravitch, the nation- introduced educators to the ally known historian of educa- concept of deeply knowing tion and a research professor of education not magicians. He understood the limits their “who” — not just where a student at New York University, blogged about of what schools can do at the same time is on an academic scale, but their capacPhil’s contribution to education: “Phillip that he understood the awesome power ity for understanding current knowledge, Schlechty was a man of deep knowledge of teachers to change lives. … He advised interests and goals. and common sense. If you read any of many schools, helping them to improve. A quote on the wall of the Schlechty his books about education, you will know He did not believe in radical disruption Center reads: “Our customers are our at once that Phil understood teaching, or earth-shattering transformation. He friends.” Phil lived that quote to its fullest learning, education and leadership. He believed in the steady and collaborative and unfailingly encouraged others to do understood that teachers are mortals, work of schools, and knew it was hard, and so as well. n

The College Football Hall of Fame and Chick-fil-A Fan Experience is 95,000 square feet of awesome and the perfect place to educate and motivate your students. They will participate in fun and interactive football-themed activities and have so much fun they won’t even realize they are learning. Combine the live Hall experience with our FREE T.E.A.M.S.™ Curriculum for a comprehensive lesson plan focused on Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics and Science.

Email: groups@cfbhall.com Telephone: 404.880.4841 cfbhall.com

@cfbhall

Henry County Meshes Academics with Career Training to Develop Life-Ready Graduates

Academy for Advanced Studies

By Christine Van Dusen

The band plays “Pomp and Circumstance,” and the graduates receive their diplomas and a handshake. But are they ready for what lies ahead? The answer, on a national scale, has been a resounding “no.” Recent studies show that while more students are graduating high school than ever before — a record 82 percent nationwide and 78.8 percent in Georgia — more than half report feeling ill-prepared for the future.

That’s not good enough for Henry County Schools. The district is among a growing number of school systems that, in addition to academics, is emphasizing job training and soft skills to help students get ready for what may come next — whether it be college, a trade school or direct placement in the workforce. “We’re challenging the stigma that there’s just college,” says John Uesseler, CEO of the Academy for Advanced Studies in Henry County. “We expose them to all their options. They can do four-year college, trade school, tech school, an apprenticeship or the military.”

While conventional wisdom has long suggested that college is the best path after high school, it’s clearly not the best path for all students, and, in the end, it’s not the only path to success in this economy. Although workers with college degrees and advanced training Continued on page 10

‘Over the past three years, I’ve had numerous conversations with parents about students who were unengaged in school and not interested. They had discipline issues, attendance issues. But when they found something to be passionate about, something they were truly enjoying, not only were their grades good at the academy, but they were also better at their home schools. Attendance got better, and they even started talking about post-secondary education when they had never talked about it before.’

tend to command higher pay, about 39 percent of jobs nationwide and in Georgia require only a high school diploma or equivalent, reports the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“There is a change in the air in terms of whether you need to go to college — more so than I have seen in 20 years,” says College and Career Readiness Specialist Susan Bowles Therriault, a principal researcher with American Institutes for Research. “We want kids to graduate with all the opportunities available to them. They can choose to go or not go to col-

lege, or into a career, and be prepared and successful.”

For Henry County Schools, preparing students for the future is a priority, and a success story. The district — with buy-in from teachers, parents, students and the community at large — is meshing traditional academic programming with advanced coursework, classes for college credit, job training and fieldwork. “Our focus for all students is that they graduate Henry County Schools as college, career and life ready,” says Aaron Randall, the secondary programming coordinator for the district.

Surveys Reveal Interests

Henry County Schools in 2013 reported a graduation rate of 78.5 percent. By 2015, that number had jumped to 84.1 percent. Why the change? Some credit the district’s personalized process for determining the right path to graduation for each student.

The process begins in middle school, when every student is encouraged to aim for some kind of post-secondary training, including technical colleges, two-year colleges, four-year universities and the military, says Wes Silvey, a co-lead counselor

Community Joins with Schools to Help Students Nail the Job Interview

By J.D. Hardin, Henry County Schools Communications Coordinator

Henry County takes a holistic approach to preparing tomorrow’s workforce. It starts with the basic job interview. Each year, career pathway students in every local high school participate in mock job interviews conducted by a diversified mix of local business owners and employees.

In advance of the interviews, business representatives are coached by work-based learning instructors at host schools. Interviewers are instructed to treat the events like real interviews, albeit shortened due to time restraints. The questions can be generic or tailored to a specific field if a student indicated a career interest ahead of time. Interviewers typically meet with

Just a few of the scores of Henry County business representatives who participate in the week-long mock interview event involving hundreds of 9th through 12th grade students. (Photo by Contina Graham)

for grades 10 through 12 at Union Grove High School. “Our counselors conduct grade-level advisement, utilizing careerinterest surveys through virtualjobshadow. org and gacollege411.com,” he says. The aim is to help students “tailor their education to their future dreams and desires.”

Increasingly, students are pursuing their dreams via the Career, Technical and Agricultural Education program, which offers vocational training in everything from agriscience and engineering, to marketing and management in partnership with the Technical College System of Georgia and the University of Georgia.

Beyond career training, CTAE emphasizes soft skills, such as appearance, attendance, attitude, character, communication, cooperation, organization, productivity, respect, teamwork and work ethic. Enrollees also participate in mock job interviews with volunteer members of the business community and education leaders. “One of the biggest things we’ve heard from business and industry is that it doesn’t matter if a student goes right to work out of high school or gets a degree — young people coming out into the workforce are greatly lacking in work ethic,” Uesseler says. “Employers want us to help students become effective problem-solvers, communicators and thinkers.” Continued on page 10

Students engage in mock job interviews with business and education leaders. (Photos by Meg Thornton)

five to 10 students.

Teachers conduct extensive lessons to prepare the teens for the all-important interviews, for which they receive grades. Students are prepped on eye contact, greetings, body language, answering questions and appropriate attire.

The number of students involved in the program has swelled, forcing many schools to extend their mock interviews over multiple days. The number of businesses participating has kept pace as well.

Finding businesses to participate in the program has eased in recent years because many interviewers now return year after year and have recruited associates and peers to join in as well. An added positive outcome is that, due to working with the students, participating members of the business community envision a strong future for the county.

Hundreds of businesses in Henry County also offer support with internships and/or part-time jobs through the work-based learning program or though the Partners in Education program. n

GA Association of Media Assistants, Union Grove HS

Photo by Contina Graham

Academy for Advanced Studies

One reason that Henry County’s academic program with community CTAE program has become so popular needs. Funding came from a $3.4 milis that its offerings have quadrupled. lion matching grant (to expand Henry Where there were once about 10 voca- County High), as well as an education tional pathways that a student could pur- special purpose local option sales tax sue as part of CTAE in each high school, (ESPLOST); donations; the Move On there are now more than 40. And that’s When Ready program; and the general thanks to the Academy for Advanced operating budget for the school district. Studies. “We’re not only striving for students to be college- and careerready, but also to try and Where once there were about 10 vocational pathways that a Henry ensure a viable workforce for today’s jobs and for future jobs,” Uessler says. County student could pursue as part of CTAE in each high school, “All of our programs are in areas that business and industry said they need there are now more than 40. folks for.” When the academy opened, about 900 students from Henry County The charter program, which is avail- High and 225 from other high schools able to all district high school students, enrolled. This school year, there are opened in 2013 inside Henry County 1,965 students, including 775 from High School after the academy found- other schools and 300 who split their ers worked with more than 70 local time between their home schools and leaders to write a charter and align the the academy. That’s close to maximum capacity for the facility. On March 1, voters approved an ESPLOST/bond referendum to fund the construction of two new schools, McDonough High and McDonough Middle. This will allow the academy to take over the Henry County High School campus, says Uesseler. “The growth has SkillsUSA students help coordinate mock interviews. Photo by Contina Graham been absolutely tremendous.” Once students are on their vocational pathways — either through CTAE alone or via the academy — and reach the age of 16 in 11th or 12th grade, they can apply for the work-based component of career-

related education. These are internships, youth apprenticeships or cooperative education opportunities that allow students to practice what they’ve learned.

One opportunity sits close to home. Georgia United Credit Union in January opened a branch inside Henry County High. Five students now work there with full-time credit union employees and learn everything from managing transactions to working on the teller line. “What they’re studying is immensely practical and applicable. They learn what it’s like to be in that industry,” Randall says.

Henry County Schools is also working with Austell-based Yancey Bros., the state’s largest Caterpillar dealer, to create a diesel technology pathway that would earn a student a technician certification. “It covers all aspects of equipment repair for Caterpillar construction equipment,” Uesseler says. “Once the students complete the program and pass hiring requirements, they will have gainful employment and the opportunity to complete their training with Caterpillar.” A pilot program is set to launch this fall.

Henry County isn’t the first district to focus intensely on post-graduation readiness and to create some sort of Academy for Advanced Studies — it’s the 28th. But whereas some districts that created academies elected to shut down the CTAE programs available inside individual high schools, Henry County took a different route.

“We had 12,000 students in career tech in the county. We couldn’t close all those programs and then expect all of those students to come to the academy. We couldn’t

Academy for Advanced Studies

Photo by Contina Graham

GA Association of Media Assistants, Union Grove HS

serve them,” Uesseler says. So they left the 279 walked the stage in May and earned the goal of possibly attending nursing current programs in place and added the diplomas. Several others received theirs school after graduation. “I’ve talked to a academy to expand options that students during summer school. “We have a few people at nursing schools, and they didn’t have in their local schools. 99 percent graduation rate that we’re can tell who has had previous hands-on

It’s too soon to measure the economic very proud of,” Uesseler says. “The end experience,” she says. “They see that the impact of the district’s focus on college game is a passion that is going to sup- students have more knowledge and a feel and career readiness, but the program- port their lifestyle. We’re getting them for it. This gives you a leg up.” ming is clearly helping students. “Over excited about what they the past three years, I’ve had numerous can do once they’re out in conversations with parents about stu- the real world.” ‘I’m doing management, upkeep, dents who were unengaged in school and not interested,” Uesseler says. “They had Lauren Burkett is indeed excited about what lies scheduling and tours of the discipline issues, attendance issues. But ahead. She’s a 15-year-old conference space here.’ when they found something to be pas- sophomore at Union Grove sionate about, something they were truly High, but she’s enrolled – Anthony Johnson, Sophomore, enjoying, not only were their grades good at the academy, but they were also in the academy and takes her traditional academic Academy for Advanced Studies better at their home schools. Attendance courses online. “I heard got better, and they even started talking people talk about the acadabout post-secondary education when emy, and the opportunities it offered,” Anthony Johnson agrees. The 15-yearthey had never talked about it before.” she says. “It opened a door for me.” old sophomore, who is enrolled at the

Last year, there were 282 seniors in She’s on the healthcare pathway, so she academy and takes his core Luella High the Academy for Advanced Studies, and takes anatomy, science and electives with School classes online, completed the law enforcement pathway. He initially thought he’d like to follow family members into that field, but he’s since decided he might rather go into business. So he’s interning as an event coordinator at the academy. “I’m doing management, upkeep, scheduling and tours of the conferPhoto by Meg Thornton ence space here,” he says. “My schedule allows me flexibility for these kinds of opportunities.” Next year, Johnson will begin the coursework for the business and entrepreneurship pathway. “When I

From left: Union Grove HS Principal Ryan Meeks, Assistant Superintendent for Human Resources Dr. Valerie Suessmith, Superintendent Rodney Bowler, District CTAE Coordinator Sharon Bonner, Union Grove HS Business Education Chair Sarah Franklin, heard about the academy, there was no hesitation,” he says. “I saw the benefit. I had the plan. There were

Union Grove HS Assistant Principal Dr. Teisha Waller, Academy for Advanced Studies so many options. I think this experi-

CEO John Uesseler and District Communications Coordinator J.D. Hardin. ence will definitely help me.” n

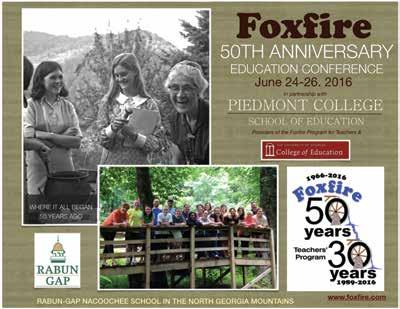

Foxfire Education: A 50-Year Treasure

By Carl Glickman, Professor Emeritus of Education, University of Georgia

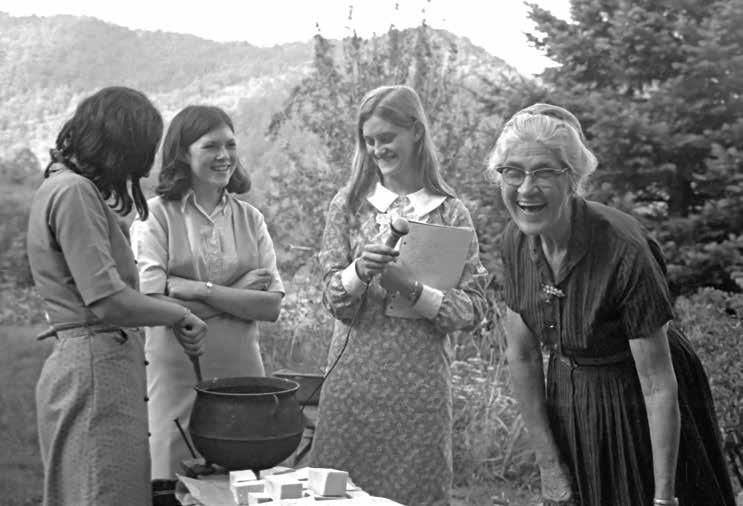

Fifty years ago, a classroom in the small Appalachian town of Mountain City in Rabun County developed a progressive educational approach that captured the nation’s attention. The approach, called “Foxfire,” is distinctive in the history of American education due to its legacy of student work outside the classroom.

“Foxfire did this, as well as any other pedagogical program, for public school students in the history of American education,” wrote Julie Lynn Oliver, a former University of Georgia researcher who examined the impact of Foxfire (Oliver, 2011). The issues faced by The Foxfire Fund Inc. — its ability to survive criminal and financial calamities and then re-emerge stable and facing a positive future — is a fascinating and instructive story. This is a Georgia story, but its past and future significance on classrooms, schools and communities is far larger.

In September of 1966, a young, first-year teacher, Eliot Wigginton, frustrated over the behavior of his bored and belligerent high school students, confronted them about their behavior. He asked them what would make English class more interesting. After a series of discussions, a final proposal was made. The students agreed to learn the state-required English curriculum of composition, punctuations and sentence usage by way of a class project. They would create a community magazine and call it Foxfire, named for the glowing, green fungus found on decaying trees in the adjacent forest.

Each issue would feature studentgenerated poetry, interviews, drawings and photos of community and family members. The first magazine sold for 50 cents and the cost of production was 65 cents. Even with modest donations from the local community, the classroom experiment was soon to go broke. But after positive reviews by editors of local and state newspapers, the demand for and price of subsequent issues increased and donations from local merchants grew. Thus, the project was saved. By 1971, the magazine had attracted widespread interest from outsiders wishing Continued on page 16

to know more about living on the land, self-sustaining farming and the pioneer ways of everyday life. That school year, the students selected their best stories from previous issues and compiled them into “The Foxfire Book” published by Doubleday. The first volume made The New York Times bestseller list.

What followed were more bestselling books (more than 9 million copies sold), a nationally distributed movie, a 32-building Foxfire Museum and Heritage Center on Black Rock Mountain, multiple archived collections of Appalachian life and three decades of courses and workshops on the Foxfire approach to teaching and learning for educators and education students across the country (see the Foxfire core practices on next page). Royalties and donations over the years have provided $1 million in college scholarships for Rabun County high school students, and new scholarships continue to be awarded every year. In 20 years of existence, Foxfire had become a national phenomenon and had established a wellendowed nonprofit — The Foxfire Fund. But tumultuous times threatened to wipe out the organization; more on that later.

Foxfire’s Impact on Education

In 1985, the book review editor for the The Washington Post, after reading the

soon-to-be-released book, “Sometimes a Shining Moment: The Foxfire Experience, 20 Years Teaching in a High School Classroom,” wrote that Foxfire “could help change our understanding of school as significantly as Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ helped change our understanding of the environment.”

The editor was overly optimistic, but Foxfire did change understandings about the potential of ordinary students to become deeply involved in school learning. The approach actualized the John Dewey progressive premise of the earlier 20th century that classroom learning needs to become a form of democratic life, whereby students actively demonstrate their acquired knowledge and skills by making immediate applications to bettering society (Wigginton, 1985). Foxfire was perhaps the best example of this premise for its time.

Oliver analyzed the impact of Foxfire on earlier Rabun County students. She wrote that Foxfire provided “extraordinary opportunities for students to build communication skills. By requiring students to conduct interviews, speak on behalf of Foxfire at various organizations … students were given opportunities that most high school students would never receive in a more conventional curriculum program.”

Furthermore, added Oliver, “Students developed a greater appreciation for their native culture and, with that, developed the confidence that they could carry themselves proudly as mountain people anywhere. The result was that Foxfire students became more productive citizens in our democracy.”

Evaluating Foxfire

My return to the Foxfire organization after an absence of more than 20 years made me think about sustainability in education and whether Foxfire could be deemed a success or failure. In the mid1980s, I headed a University of Georgia network of public schools, called the Georgia League of Professional Schools, focused on democracy, education and public purpose (Glickman, 1993). We partnered with Foxfire to provide pro-

fessional development to K-12 teachers eager to engage their students in learning activities that extended into their communities. That collaboration with Foxfire continued until 1992.

In every education endeavor, unilateral claims of success and failures are highly suspect. Education is a social science, not a hard science of strictly controlled studies, and a major factor is the period of time over which a program can be evaluated: five, 15 or 50 years. Since this is Foxfire’s 50th anniversary, I chose the entire period of 50 years to determine if Foxfire’s approach to education has been a success.

Foxfire clearly benefited many students in Rabun County and it continues to do so. It also had a major influence on individual classrooms in schools that were members of the Foxfire Regional Networks in the 1980s and 1990s, according to the majority of teacher survey responses. But today, the name Foxfire is not often heard in describing education practices that support student activities and community service. To gain insight, I reviewed research on activity-centered programs that have kinship to the core practices of Foxfire. Those programs have titles such as project-based learning, place-based education, deep learning, academic service learning, experiential learning and civic learning. Studies of these programs show student success in academic achievement, higher interest in learning, lower dropout rates, progress beyond school in both higher education and professional careers, and greater participation as adult citizens in local and state affairs (Glickman, 2015). I wondered whether an educational approach to learning that is no longer identified by its name could be claimed as a success or failure? I would argue it has been a success because, as a forerunner, it influenced many of our current progressive education practices. Educational approaches that promote student engagement and student contribution remain a glaring need for all students. Unfortunately, such experiential, inquiry-oriented learning is often only found in classes of honor and gifted students and in schools that have a preponderance of students from middle to high socioeconomic backgrounds. The students who most need an active and contributory education, receive it the least (Levinson, 2012, Levine, 2013, and “Guardian of Democracy,” 2011). Navigating Troubled noted tumultuous times with Foxfire. It has no obvious reayears. After Foxfire reached and its founder received the molestation, pleaded guilty, from any further involvement with the program. In 1992, a single count of molestation, that his victims numbered betrayal persist, some of the students who were among supporters of the Firefox program. In fact, students from those same classes posted downtown businesses asking the community to keep the Foxfire program and museum alive. The students prevailed and Foxfire continued its mission. Yet, for many years, it was tough going.

An immediate danger of financial bankruptcy was avoided by a Foxfire board member who donated his time to negotiate legal settlements. Teacher networks were closed due to jeopardizing the funding for the museum, local teachers, courses and student scholarships. The Foxfire teacher educational program became part of nearby Piedmont College; other collaborations were organized with faculty and staff at the University of Georgia. Several staffing changes and reorganizations have taken place, and in 2000, a new executive director and museum curator were hired to stabilize the organization and launch a 50th anniversary initiative.

I surmise that Foxfire will remain vibrant in the place it was created. It belongs to the community as an irreplace-

Continued on page 18

Waters

Earlier in this writing, I son to be planning its next 50 its national iconic stature MacArthur Genius Award, he was indicted for child served prison time, moved out of state and was removed Wigginton was convicted on but prosecutors contended many more. Although anger and feelings of hurt and his claimed victims remained notices on the windows of able contribution to the world, showing Foxfire Core Practices • Learner choice and design infuse the collaborative work of teachers and learners. • Teachers are facilitators and collaborators. • The work is designed to internalize the academic disciplines. • Learners are able to make connections with other schoolwork, their community and the world. • Active learning, in an atmosphere of trust and equity, characterizes classroom activities. • The learning process entails imagination and creativity. • Classroom work includes peer teaching, small group work and teamwork. • The audience for learner work extends beyond the teacher, thereby providing inspiration and broadening feedback. • Challenging, ongoing assessments promote deeper understanding and higher levels of achievement in subsequent work. • Reflection, an essential activity, takes place at key points throughout the work.

Foxfire will hold its the staying power of students education summer and schools partnering with conference, a celebration their community to make of the past and future, at education a contribution to both. Most fittingly, this past October while I was completRabun-Gap Nacoochee School June 23-25. It is ing this essay, Foxfire received open to all educators. To the 2015 Georgia Governor’s register and learn about Awards for the Arts and Humanities for its sustained contributions to the welfare of other Foxfire programs, visit foxfire.org. schools and communities.

It is unrealistic to think that every classroom and school, Carl Glickman is a University Professor along with its community, could replicate Emeritus of Education at the University of what happened more than 50 years ago Georgia and a board member of the nonin Rabun County, resulting in best-selling profit The Foxfire Fund Inc. Learn more by journals and books and a vast museum. visiting foxfire.org or contacting Glickman at Yet it is realistic and imperative to expect cglick@uga.edu. that Georgia students today can apply what they are learning in English, math, Disclaimers: A shorter version of science, history and the arts to making this essay was published and reprinted their communities healthier, more caring, with permission by Phi Delta Kappa — economically viable and aesthetically bet- Glickman C, “50 Years Later, Does Foxfire ter places to live. That would be the ulti- Still Glow?” February, 2016. This essay is mate success of Foxfire and for our state not an official position or statement of The and nation. n Foxfire Fund Inc.

A small college doing big things!

Join the 8,000–plus Georgia teachers who have earned Bachelor’s, Master’s, Specialist, and Doctoral degrees from one of Piedmont’s PSC-approved programs.

Courses are offered at our campuses in Demorest and Athens and off–campus sites across Georgia.

BA • MA • MAT • EDS • EDD Certification-only and non-degree programs also available 800.277.7020 | piedmont.edu

REFERENCES

Glickman, C. (1993). “Renewing America’s Schools: A Guide for Schoolbased Action.” San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Glickman, C. (2015, March 20.). “Foxfire Lessons of the Past to Inform the Future: An Evidenced-based Compilation.” Unpublished report to The Foxfire Fund Board.

Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools. (2011). “Guardian of Democracy: Report of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools.” Silver Spring, MD: Author. civicmissionofschools.org.

Levine, P. (2007). “The Future of Democracy: Developing the Next Generation of American Citizens.” Medford, MA: Tufts University Press.

Levinson, M. (2012). “No Citizen Left Behind.” Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Oliver, J. (2011). “The Story and Legacy of the Foxfire Cultural Journalism Program” (doctoral dissertation). University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Rechtman, J. (2015, November 2). “Jamil’s Georgia: Foxfire, Still Aglow — After Catastrophic Event, An Organization’s Lessons Learned.” The Saporta Report. saportareport.com/foxfire-still-aglow-after-catastrophic-eventan-organizations-lessons-learned/.

The Washington Post, Book review of Wigginton, E. (1985). “Sometimes a Shining Moment: The Foxfire Experience, 20 Years Teaching in a High School Classroom.” NY: Anchor Press/ Doubleday.

Wigginton, E. (1985). “Sometimes a Shining Moment: The Foxfire Experience, 20 Years Teaching in a High School Classroom.” New York, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday.